Introduction

Present-day companies operate in a highly complex and dynamic industrial environment. Globalization and the resulting heightened competition explain the need for some companies to turn to strategic alliances as a way of improving their performance. For such companies, strategic alliances involve pooling their tangible and/or intangible resources to achieve their strategic objectives (Lorange and Roos, 1982).

In recent years the rise of strategic alliances has attracted the interest of many researchers in strategic management (Kogut, 1988; Doz, 1988; Nielsen, 2007; etc.). However, it should be noted that most studies focus on strategic alliances between multinational firms. Analyses of strategic alliances between organizations of different sizes, commonly referred to as “asymmetric alliances”, whether in developed or developing countries, are still few and far between. One can count for example the works of Chen and Chen, 2002; Beamish and Jung, 2005; Katila et al, 2008; Nieto and Santamaria, 2010; Diestre and Rajagopalan, 2012; etc. Most authors showing an interest in asymmetric alliances argue that asymmetries between partners negatively influence the performance of such alliances (Sarkar et al, 2001; Pérez et al, 2012). Similarly, it has been argued that in an alliance where partners are fundamentally different, trust development can be a daunting task which may subsequently affect the results of the relationship (Bucklin and Sengupta, 1993; Doz, 1988). Consequently, the direct and indirect effect of asymmetries on performance is negative. However, several authors take a very different view. For example, Yeheskel et al. (2001) suggest that the dissimilarity in size enables parent organizations to enjoy each other’s unique characteristics. In turn, Beamish and Jung (2005), and Dikmen and Cheriet (2014) found a nonsignificant effect of size asymmetry on alliance performance. Finally, there is a certain amount of theoretical controversy surrounding the effects of size asymmetry between partners on alliance results. These contrasting views make the generalization of empirical results more difficult.

The purpose of this contribution is to overcome these controversies by exploring through case studies the direct and indirect (trust) effects of size asymmetry on the alliance performance. Our empirical study covers asymmetric alliances engaged in by ten French SMEs operating in the aircraft manufacturing industry. Only few studies on strategic alliances focus on French SMEs in alliances with large multinational corporations (MNCs), and none of them has examined the effects of size asymmetry on the performance of such alliances. Furthermore, the aircraft industry presents a number of asymmetric strategic alliances. In our contribution, performance is addressed from the perspective of one of the partners, the SME.

This paper is organized as follows. First we present a literature review on both a direct and trust-mediated relationship between size asymmetry and performance. Next, we describe the method that we adopted. We then present our results and discussion. The results reported here are a set of propositions challenging traditional views on the relationship between size asymmetry and the results of asymmetric alliances. The article concludes by outlining the implications, limitations and areas for future research.

Background

The concept of asymmetric alliances is one of the most controversial in the field of strategic management research. Indeed, there is no single accepted framework in terms of either the definition of asymmetric alliances or their main characteristics. Generally, asymmetric alliances are referred to cooperative arrangements between MNCs and SMEs aimed at pursuing mutual strategic objectives. Thus the asymmetry is based a priori on the size differential. This interpretation of asymmetric alliances is relevant (Pérez et al. 2012) because size asymmetry is the source of other differences between partners (i.e. geographical origin of the partners; level of development; experience in cooperation; growth rate; organizational culture; specificity of the assets exchanged; resources and competencies; absorption and learning abilities; innovation capacity).

Extant research in sociology, marketing and inter-organizational theory have long since stressed the fact that dissimilarities between social actors can make pair interactions difficult (Parkhe 1991). Similarity appears to support attraction between parties, which in turn promotes the development of positive attitudes and leads to favorable results. For example, among research which has tried to identify the effects of size asymmetry on the partnership’s results, most of them have maintained that differences resulting from size asymmetry negatively affect alliance performance. Indeed, size asymmetry usually results in an imbalance in the management structure (Yan and Gray, 1994). It also results in a lack of a strategic “fit” between parents (strategic and organizational incompatibilities) which may affect both the quality of the relationship and the partners’ satisfaction (Geringer and Hebert 1991; Hill and Hellriegel, 1994).

In a transaction cost approach, strategic alliances which are asymmetrical in size appear to involve high governance and coordination costs (Doz 1988). In order to work together effectively, partners generally commit resources to coordinate their internal procedures and policies. Therefore, according to this perspective, the asymmetry in the partners’ size has a negative influence on the performance of the alliance (Yeheskel et al, 2001). In addition, it has been noted that size asymmetry may involve a one-way learning process to the advantage of the dominant partner (Inkpen and Beamish, 1997). This increases the likelihood of relationship instability and can lead to the dissolution of the alliance (Park and Ungson, 1997).

Besides the direct effects of size asymmetry on performance, the literature has shown that this dissimilarity can indirectly affect performance through the trust variable. Trust can be conceptualized as a generalized expectation regarding an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Partners, who trust each other generate more profits, better serve their customers and are more adaptable (Kumar 1996). According to Bierly III and Gallagher (2007), it seems that size asymmetry negatively affects trust between the partners of the alliance. For these authors, “The firm will have more confidence in its ability to predict the behaviour of its partner and understand its routinised regimes if they are more similar. In the same way, two firms that are of similar size are more likely to trust each other because there is less threat of the larger firm using its power to take advantage of the smaller partner” (p.141). Therefore, size similarity leads to a convergence which facilitates mutual understanding and discourages the emergence of competitive trends, strategic conflicts and hidden agendas, all of which are detrimental to the mutual relationship and trust (Doz 1988).

Taking this into account, one may assume an indirect relationship between size asymmetry and performance due to the relational capital between partners.

Research Methodology

Empirical Background and Justification

Our empirical investigation focuses on ten cases in which French SMEs enter into non-equity asymmetric alliances in the aircraft manufacturing industry. These alliances are typically contractual and do not involve the creation of a separate legal entity for the coordination and management of the project. Indeed, in this paper, we can delineate the partnerships essentially into functional contractual alliances (i.e. joint project for technological development, technology transfer relationship, etc.) and commercial contractual alliances namely original equipment manufacturing contract (Chen and Chen, 2002).

The choice of aircraft manufacturing as a research field is justified firstly by the fact that the aircraft manufacturing industry is a high technology sector characterized by a number of alliances between innovative SMEs and large industrial groups. According to the annual report by GIFAS (Groupement des Industries Françaises Aéronautiques et Spatiales ), in 2013 the R&D expenditure of the aerospace industry represented 14.7% of its total turnover. Secondly, in the aircraft industry, the pace of innovation in SMEs can be considered as fundamental for the big players (aircraft and components manufacturers) given the role that SMEs play in the production and maintenance of their products. Indeed, the components of aircraft manufactured by MNCs are produced by their partners, including numerous contract manufacturing SMEs. Finally, from a theoretical point of view, the choice of SMEs as a study object is justified by the near absence of research analyzing the performance of strategic alliances from the SME’s perspective.

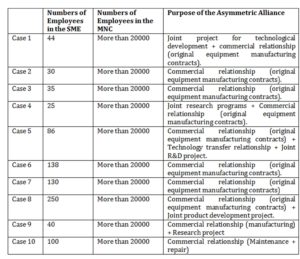

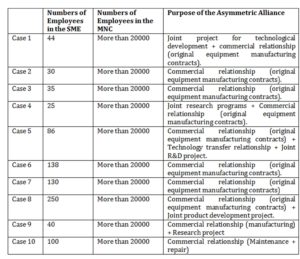

Table 1 describes the ten asymmetric alliances studied in this research. They are all long-standing partnerships and are in their operational phase.

Table 1: Asymmetric Alliances Studied

We consider that the alliance partners are asymmetric in size when one partner is an SME and the other one is an MNC. Size is appraised in terms of number of employees in the company (Pérez et al, 2012). Companies are considered as SMEs when their headcount is between 20 and 250, in accordance with the European Commission definition. MNCs are enterprises with operations in different countries and with a workforce of more than 500.

In this research we adopt a multidimensional approach to performance analysis. Indeed, as our goal is to understand the phenomenon of asymmetric alliances in its entirety, it seems necessary to evaluate performance by simultaneously considering subjective and objective criteria. We therefore integrate three dimensions of performance into our performance analysis framework (relational, financial and organizational learning). Each dimension of performance addressed in this research is defined by means of subjective assessments by the SMEs involved. In this research we do not address the differences in perceptions that may exist between partners. As pointed out by Geringer and Hebert (1991), the collection of perceptions of only one partner may be sufficient to obtain reliable and efficient data.

Data Collection and Processing

The qualitative method of a multiple case study (Yin, 1984) was chosen for this research. This methodological choice was guided by our goal of achieving a more in-depth understanding of asymmetric strategic alliances phenomenon and the factors affecting their performance. This methodological choice is also guided by the fact that we are working on a sensitive subject and focusing on an industry with a significant culture of secrecy. It is very difficult to get answers from questionnaires in this sector. In our opinion, it is easier to get answers from open interviews, as we did.

With this in mind, for each SME in our sample we conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews, each lasting about 1 hour to 1 hour and a half. Each respondent is closely involved in the conduct of their company’s asymmetric alliances (Director General, CEO, Commercial director, Director of Operations). Each of our interviews resulted in a thematic coding according to items identified in our theoretical model and transcripts (King 1998). Further, the qualitative analysis was manually conducted.

In addition to data derived from our semi-structured interviews, we used secondary data in order to complete our analysis (public data, studies conducted by recognized organizations, and trade press articles). The use of multiple evidence sources helps to develop a case study (Eisenhardt, 1989).

Finally, we performed the relevant organization and reduction of all data collected in order to compare and understand similarities and differences between the ten asymmetric alliances studied, along with their effects on performance.

Results and Discussion

Direct Relationship between Size Asymmetry and Alliance Performance

Prior research has suggested that the asymmetry of size impacts negatively the performance of asymmetric alliances (Parkhe, 1991; Inkpen and Beamish, 1997; Yeheskel et al, 2001). In this section, we describe the observations that support or contradict this theoretical assertion. First, we observe, considering our results, that the direct effects of size asymmetry on the results of alliances may be assessed in terms of financial performance, organizational learning and relational performance.

Financial performance. In all cases studied (ten out of ten), we observed an increase in turnover and market share for the SME despite the existence of such size asymmetry between partners. This point is illustrated by the following comments from our respondents.

“Despite any differences, the relationship generates market share …”, Director General of the SME in Case 1;

“There has been a significant increase in our sales and market share. For example in 2011 our level of growth was 325%”, Director General of the SME in Case 2;

“There has clearly been an increase in our turnover and market share. Our growth last year stemmed from the fact that we signed new contracts, but it is also related to the fact that our current client is satisfied with what we have provided, and they recommended us”, Director General of the SME in Case 3;

“When we are involved in a technology transfer alliance with X for all airports, there are royalties; and in terms of turnover, it’s very significant”, Commercial Director of the SME in Case 5.

Organizational learning. The majority of SMEs surveyed (9 cases out of 10) observed an increase in their organizational learning, in terms of both development of their knowledge base and transfer of the MNC’s managerial competencies to the SME.

Development of their knowledge base: asymmetricallianceshave enabledtheSMEs to improve their technical and innovation skills(i.e. improvement in manufacturing processes, acquisition of newtechnological expertise, product development). Similarly,through thesealliances, the SMEs showed adevelopment in theirexperiencein management of asymmetricalliances

“We are acquiring knowledge and new technological expertise. We are also learning manufacturing and product development processes, management skills,…”, Director of Operations of the SME in Case 6.

“In these relationships you will learn a lot. It is not necessarily a transfer of knowledge. They encourage us to innovate further. Their needs drive us to think and innovate”, Director General of the SME in Case 4.

Transfer of MNCs’ managerial competencies to SMEs: in theirasymmetricalliances, SMEs have benefited fromMNCsin terms of orientation and competenciesin organizationaland management processes. This hasenabled themto become more structuredby improvingand formalizingtheirinternal management processes.

“We very quickly modeled our process on theirs …”, CEO of the SME in Case 9.

“We are growing organizationally by working with them. We can copy their organizational models, yes, absolutely”, Commercial Director of the SME in Case 10.

The data from this research indicate that despite size asymmetry between partners, asymmetric alliances seem to be effective relationships generating positive quantitative results. These positive results are explained by the existence of complementarities between partners’ resources and competences. The combination of a small company’s resources with those of a larger one opens up opportunities for synergies (Harrigan, 1988; Parkhe, 1991; Sarkar et al, 2001) that improve both their economic efficiency (increase in turnover and market share) and their strategic private benefits (organizational learning). As highlighted by the respondent in Case 4, “On one hand, without them we would not have the money and would have to close. It’s that simple … On the other hand, they come to us for our expertise because it is not necessarily their job, their core business … There is no choice”. Once pooled, these resources and competencies produce important outcomes for both partners.

Ultimately, asymmetry in terms of size has no negative effect, either on financial performance or on organizational learning.

This result corroborates the findings of Beamish and Jung (2005), and Dikmen and Cheriet (2014), who point to the absence of a relationship between asymmetry of size and alliance performance. It should however be noted that it is difficult to draw a comparison with previous studies since we used different proxies to define size asymmetry. Furthermore, our results do not confirm the negative link between size asymmetry and organizational learning as identified by Inkpen and Beamish (1997).

We suggest from our observations that,

Proposition 1: the asymmetry of size does not negatively affect the financial performance of the asymmetric alliance.

Proposition 2: There is a positive relationship between the asymmetry of size and organizational learning.

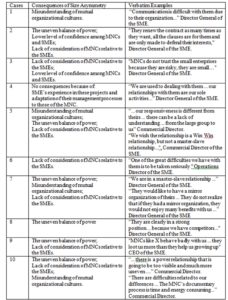

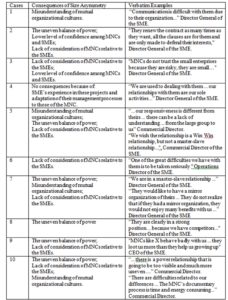

Relational performance. Our investigation reveals the existence of relational difficulties between the SMEs and MNCs involved in asymmetric alliances (9 cases out of 10). The analysis of Table 2 highlights that the reason for these difficulties is mainly the uneven balance of power between MNCs and SMEs.

Talking about the asymmetric relationships of his SME, the Commercial Director in Case 10 argued that “… there is a power relationship that is going to be too visible and much more uneven …. We will be much more at their behest … they are trying to show their full power. Actually, they are not trying, they are showing it.”

Given their size, MNCs tend to establish a relationship of dominance over their smaller and weaker partners. This results in a certain directiveness by the MNCs during the conduct phase. The SMEs then feel exploited and perceive the MNCs’ behavior as opportunistic and lacking in respect and trust. All these factors create a sense of frustration among the SMEs and make the relationship more confrontational for them, as reflected by these comments:

“They call it partnership, but there is no partnership agreement. There are agreements between an ogre who crushes an ant…”, Director General of the SME in Case 2;

“We are in a master-slave relationship … the lords are the MNCs and the beggars are the subcontractors; there is a rather condescending relationship”, Director General of the SME in Case 7.

Table 2: Effects of Size Asymmetry on Relational Performance

Additionally, it is clear from our results that size asymmetry often results both in an imbalance in terms of the partners’ management structure and in organizational incompatibilities between them that can lead to mutual misunderstandings (Park and Ungson, 1997; Johnson et al, 1996). These consequences in turn negatively affect the quality of the relationship (Doz 1988; Yan and Gray 1994; Geringer and Hebert, 1991; Hill and Hellriegel, 1994). Finally, it can be argued that size asymmetry resulting in organizational culture asymmetry will therefore have the same negative effects on relational performance.

Finally, our results allow us to establish a direct and significant negative relationship between size asymmetry and relational performance. In formal terms,

Proposition 3: There is a negative relationship between size asymmetry and relational performance.

Indirect Relationship between Asymmetries and Alliance Performance

Literature emphasizes the existence of a negative relationship between size asymmetry and the development of trust between the alliance partners. Responses relative to that assertion are categorized into two distinct groups, the cases that corroborate previous studies and those that do not.

For the first group (5 cases out of 10 with a dual response from Case 9), size asymmetry negatively influences the development of trust between an SME and a multinational involved in an asymmetric alliance. Firstly because of the power relationship established by the multinational relative to the SME. This result corroborates the findings of Bierly III and Gallagher (2007) which sustains that in case of size asymmetry, the larger firm can use its power to take advantage of the smaller partner. Secondly, because of the SME’s lack of credibility. Due to its size, less substantial resources and simpler organization structure, the SME is seen as a risky organization and seems less credible to MNCs. The perception of this lack of credibility negatively affects the development of trust between partners.

For the second group (6 cases out of 10 with a dual response for case 9), size asymmetry has no negative impact, either on trust between partners or on the development of that trust. Indeed, despite relational difficulties arising from size asymmetry, trust in asymmetric alliances can continue to develop. This will happen if, on the one hand, the SME respects its commitments and satisfies the needs of the multinational, and on the other hand, if both partners seek to exploit complementarities arising from their different resources and make efforts to understand each other’s organization. This result does not support prior research that supposes a negative relationship between size asymmetry and trust (Doz, 1988; Bierly III and Gallagher, 2007).

Overall, we do not observe any significant indirect effects of asymmetry in size on the overall performance of asymmetric alliances. Firstly, because this asymmetry affects trust between partners to a lesser extent. The relational performance is therefore indirectly affected only slightly. Secondly, because partners’ financial performance and organizational learning remain positive even in the event of a negative relationship between size asymmetry and trust.

Given these results, we propose these relationships,

Proposition 4: There are no significant effects of asymmetry in size on trust between partners.

Proposition 5: There are no significant indirect effects of asymmetry in size on the overall performance of asymmetric alliances.

Conclusion, Implications and Limitations

The main objective of this contribution was to study the effects of size asymmetry between SMEs and MNCs on the performance of their alliances. The findings are a set of propositions which allows studying the direct and indirect effects through trust of asymmetries in terms of size on the performance of asymmetric alliances. Two main results arise from this study. First, size asymmetry can cause relationship problems between partners. However, despite this asymmetry between partners, alliances generate positive results in terms of financial performance and organizational learning due to the complementarity between the resources of the SMEs and the multinationals involved.

This research has several theoretical and managerial implications. From a theoretical perspective, our results indicate the importance of the partners’ characteristics and the effects of these characteristics on trust (relational capital) in explaining the performance of an asymmetric alliance. The direct and indirect effects of size asymmetry between partners on alliance results remain largely underexplored from a theoretical viewpoint. In addition, to our knowledge there is no research on asymmetric alliances that analyzes the relationship between size asymmetry and performance by adopting a multidimensional approach to performance. Most prior studies that address this relationship analyze performance in terms of survival (Harrigan, 1988; Kogut, 1988, Beamish and Jung, 2005), longevity (Parkhe, 1991) and effectiveness (Yeheskel et al, 2001). Our results highlight the importance of considering a multidimensional approach to performance in order to obtain a global vision of the consequences of asymmetric partnerships.

From a managerial perspective, our results may provide SMEs and MNCs involved in asymmetric alliances with certain means to manage and cope with the relational difficulties they face. It is clear from this research that trust is one of the key success factors of asymmetric alliances. It promotes cooperation and reduces the risk of opportunistic behavior and conflict between partners. When partners trust each other, they generate more profit and serve their customers better (Kumar 1996). However, previous research has confirmed the existence of a negative relationship between asymmetry in size and trust building. Our results emphasize that despite this asymmetry between partners, trust can be developed and can continue to grow if the following conditions are respected: the SME meets the commitments made towards its bigger partner; the partners’ aims are to take advantage of complementarities arising from their different resources and competences; and finally the partners understand each others’ procedures and mutually adapt their different organizations. SMEs should consider these factors before engaging in asymmetric alliances and should continue to do so during the conduct of these relationships.

While this study makes significant contributions to the literature on asymmetric alliances, its potential limitations should be highlighted. First, we collected our data from only one side of the alliance (the SMEs). The extent to which the perceptions of all partners would have converged is unknown. Next, our sample size is relatively small, as our empirical analysis was limited to ten asymmetric alliances, although they were carefully selected within the aircraft manufacturing industry in France. Thus a generalization of our results to other cases and other industries should not be carried out without due care. In this perspective, future avenues of research could use this model on larger samples in different industries and diverse geographical areas.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Beamish, PW and Jung, J.C. (2005), ‘The Performance and Survival of Joint Ventures with Asymmetric Parents,’ International Business Review 10(1), 19 – 30.

- Bierly III, PE and Gallagher, S. (2007), ‘Explaining Alliance Partner Selection: Fit, Trust and Strategic Expediency,’ Long Range Planning 40(2), 134 ”‘

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Bucklin, LP and Sengupta, S. (1993), ‘Organizing successful co-marketing alliances,’ Journal of Marketing 57(2), 1 – 32.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Chen, T and Chen, J. (2002), ‘Asymmetric strategic alliances: A network view,” Journal of Business Research 55(12), 1007”‘1013.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Cheriet, F and Guillaumin, P. (2013), ‘Les déterminants de la satisfaction des partenaires engagés dans des coopérations inter-entreprises: Cas des fruits et légumes en Méditerranée,’ Revue Management International 17(4), 210-224.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Diestre, L and Rajagopalan, N. (2012), ‘Are all ‘sharks’ dangerous? new biotechnology ventures and partner selection in R&D alliances,’ Strategic Management Journal 33(10), 1115”‘1134.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Dikmen-Gorini, L and Cheriet, F. (2014), ‘Performance des partenaires locaux dans les coentreprises internationales en Turquie: La notion d’asymétrie partenariale a-t-elle du sens?’ proceedings of the 23rd international conference of AIMS, Rennes, 26-28 May.

- Doz, Y.L. (1988) ‘Technology Partnerships between Larger and Smaller Firms: Some Critical Issues’ in Contractor F. J. and P. Lorange (ed), Cooperative Strategies in International Business: Joint Ventures and Technology Partnerships Between Firms, Emerald Group, 317 ”‘

- Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989) ‘Building Theories from Case Study Research’, The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532 ”‘ 550.

- Geringer J.M. (1988) Joint Venture Partner Selection: Strategies for Developed Countries, Quorum Books, New York.

- Harrigan, K.R. (1988) ‘Strategic Alliances and Partner Asymmetries’ in Contractor F. J. and P. Lorange (ed), Cooperative Strategies in International Business: Joint Ventures and Technology Partnerships Between Firms, Emerald Group, 205-226

- Hill, RC and Hellriegel, D. (1994), ‘Critical Contingencies in Joint Venture Management: Some Lessons from Managers,’ Organization Science 5(4), 594”‘

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Inkpen, AC and Beamish, P.W. (1997), ‘Knowledge, Bargaining Power, and the Instability of International Joint Ventures,’ The Academy of Management Review 22(1), 177”

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Johnson, J.L., Cullen, J.B., Sakano, T. and Takenouchi, H. (1996) ‘Setting the Stage for Trust and Strategic Integration in Japanese-U.S. Cooperative Alliances,’ Journal of International Business Studies, 27(5), 981”‘

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Katila, R., Rosenberger J.D. and Eisenhardt K.M. (2008), ‘Swimming with sharks: Technology ventures, defense mechanisms and corporate relationships,’ Administrative Science Quarterly 2(53), 295”‘332.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- King, N. (1998) ‘Template analysis,’ in G. Symon and C. Cassel (ed) Qualitative methods and analysis in organizational research: A practical guide, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications Ltd, 118”‘134.

- Kogut, B. (1988) ‘Joint Ventures: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives,’ Strategic Management Journal, 9(4), 319”‘

Google Scholar

- Kumar, N. (1996) ‘The Power of Trust in Manufacturer-Retailer Relationships,’ Harvard Business Review, 74, 92”‘106.

- Lorange, P and Roos, J. (1982) Strategic Alliances: formation, evolution and implementation, Basil Blackwell, Londres.

- Morgan, RM and Hunt, S.D. (1994), ‘The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing,’ Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 1-20.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Nielsen, B.B. (2007). ‘Determining international strategic alliance performance: A multidimensional approach,’ International Business Review, 16(3), 337”‘

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Nieto, MJ and Santamaría, L. (2010), ‘Technological Collaboration: Bridging the Innovation Gap between Small and Large Firms,’ Journal of Small Business Management 48 (1), 44”‘69.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Park, SH and Ungson, G.R. (1997), ‘The Effect of National Culture, Organizational Complementarity, and Economic Motivation on Joint Venture Dissolution,’ The Academy of Management Journal 40(2), 279”‘

- Parkhe, A. (1991) ‘Interfirm Diversity, Organizational Learning, and Longevity in Global Strategic Alliances,’ Journal of International Business Studies, 22(4), 579”‘

- Pérez, L., Florin, J., and Whitelock, J. (2012), ‘Dancing with elephants: The challenges of managing asymmetric technology alliances,’ The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 23(2), 142”‘

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Sarkar, M., Echambadi, R., Cavusgil, S. and Aulakh, P. (2001). ‘The influence of complementarity, compatibility, and relationship capital on alliance performance,’ Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(4), 358”‘

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Yan, A and Gray, B. (1994), ‘Bargaining Power, Management Control, and Performance in United States-China Joint Ventures: A Comparative Case Study,’ The Academy of Management Journal 37(6), 1478”‘

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Yeheskel, O., Zeira, Y., Shenkar, O., and Newburry, W. (2001). ‘Parent company dissimilarity and equity international joint venture effectiveness,’ Journal of International Management, 7(2), 81”‘104.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Yin, R. (1984) Case study research, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.