Introduction

The use of information technology within government agencies/departments is not a new phenomenon but it was there since the 50s and 60s (Picazo-Vela et al., 2011). At that time, its use by government agencies was mainly for internal operations and it was not employed for information dissemination or for facilitating interactions between government departments and their citizens (Unsworth et al., 2012). In comparison, businesses were quicker to adopt social media, particularly for customer engagement, and social media fast became an integral component of information technology strategy (Dadashzadeh, 2010). The need for social media tools’ (e.g. Facebook and Twitter) inclusion in government strategy was driven by the ability of this technology to change and improve the way various stakeholders communicate with each other, such as the interaction of citizens with their governments (Kuzma, 2010).

Governments around the world have started to realise that social media tools could play a crucial role in re-engineering the government-citizen relationship, creating transparent governance and transforming the current government systems (Picazo-Vela et al., 2011). As a result, many government agencies are looking to expand their adoption of social media in order to improve the quality of their service provision and to enable greater citizen engagement (Hrdinová et al., 2010).

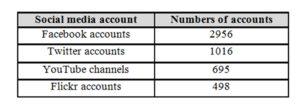

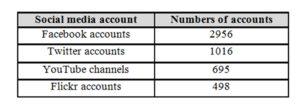

Recent research has indicated that government agencies are increasingly adopting social media (Eyrich et al., 2008). “As of April 2012 a total of 699 organizational units (including initiatives, teams, and individual senior officials’ accounts) in the U.S. federal government units have created the following number of accounts in different social media” (Mergel, 2013)

Table (1): U.S. federal government units’ accounts

Nowadays many governments worldwide are reserving budgets to harness social media, in order to transform government services through digital engagement between government agencies and their customers. There are several reasons for the adoption of social media by government agencies, including the ability to share timely information within and across government agencies and to disseminate information to the public (Picazo-Vela et al., 2011). Most government agencies are using social media for information dissemination on official government websites (Kuzma, 2010). Local governments can use social media sites to procure and position resources and local knowledge, monitor and resolve problems and engage their constituents in an atmosphere of cooperation [Kuzma, 2010].

The use of social media by government agencies is a topic that has attracted the attention of people in academia and industry as to how to make the best use of it and avoid the side-effects of using or not using it (Lawati, 2011; Charron et al., 2006; digitalgov.gov, 2014; Golbeck et al., 2010; Bertot et al., 2010a; Bertot et al., 2012a; Bertot et al., 2012b; Jaeger et al., 2012; John C. Bertot et al., 2010; John Carlo Bertot et al., 2010; Lazer et al., 2009; Picazo-Vela et al., 2011; Picazo-Vela et al., 2012; Rey, 2011; Wigand, 2011; Effing et al., 2011; Ammari, 2012; Al-Qassemi, 2012).

This literature review assesses and synthesizes the benefits of using social media as well as examining the obstacles preventing its fully-fledged usage. However, its main focus is on exploring how government agencies worldwide are using social media.

The rest of this paper is laid out as follows. The next part is a literature review, which includes definitions, social media categories, the benefits of using social media for government agencies, and the obstacles in adopting it. This is followed by the research methodology, followed by the uses of social media in government agencies worldwide. The findings are discussed and the conclusion, contributions, future research and set or recommendations are highlighted at the end of the paper.

Overview of Social Media

Definitions

In exploring the definition of ‘social media’, it was found that the terms ‘social media’, ‘social media tools’, ‘social networks’, ‘social networking’, ‘social networking tools’, and ‘social networking sites’ are all overlapping. However, ‘social networks’ are traditionally defined as groups of people who, for example, share interests and/or activities. ‘Social networking’ is the act of participating or interacting with one another within these social networks (Al-Badi, 2013). Social networking sites are the websites where the interaction happens (Cohen, 2011; DigitalLikeness, 2008). Boyd (2008) defines social networking sites as: “web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by the system” (Boyd, 2008). Examples of the most popular and well-known social networking sites are Facebook, Twitter, Blogger, MySpace, Digg, Google+, LinkedIn, Second life, YouTube, and Flickr, to name but a few. Social networking sites deliver content through communication, collaboration/authority-building, multimedia, reviews and opinions, micro-blogging, publishing, photo sharing, entertainment and brand monitoring (Bard, 2010). They provide techniques and technologies such as aggregators, audio, video, live-casting, RSS, crowd-sourcing, virtual worlds, gaming, search, conversation apps and Wikis.

Kaplan and Haenlein (2010) define social media as “a group of internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content”. Social media is just like other media – a means of communicating and exchanging information. It offers the opportunity to create or disseminate facts, opinions, arguments… etc. in many forms (video, audio, image, text). Therefore it can be defined as a platform that provides the tools for self-expression in various forms. Groups of people with common interests become associated on social media (SocialMediaToday, 2010).

Gov 2.0 is another important term, that refers to the process of utilising the collaborative technologies to create an open-source computing platform in which government, citizens, and innovative businesses can improve transparency and efficiency (O’Reilly, 2009). Harper (2013) defined it as “putting government in the hands of citizens (Harper, 2013). Gov 2.0 is based on Web 2.0 technologies which refer to a new era of Web-enabled applications and tools such as blogs, micro blogs, podcasts, Really Simple Syndication (RSS), social networking sites, video sharing, web chat, and wikis used to encourage citizen participation, collaboration and transparency (Howard, 2013). Hilgers and Piller (2011) defined it as the “external collaboration and innovation between citizens and public administrations can offer new ways of citizen integration and participation, enhancing public value creation and even the political decision-making process” (Hilgers and Piller, 2011).

Social Media Categories

Social media are part of Web 2.0, which is growing exponentially. They have been categorized in different ways. For example, the British Department for Communities and Local Governments put forward the idea of categorizing social media into profile-based social networks, content-based social networks, white-label social networks, multi-user virtual environments, mobile social networks, micro-blogging/presence updates, social search, local forums, and thematic websites (Communities.gov.uk, 2008). Kietzmann et al. (2011) propose a social media categorization based on functionality and they call it the honeycomb of social media (sharing, presence, relationships, reputation, groups, identity, and conversations). Shrivastava et al. outline the major Web 2.0 services and applications, where they list blogs, wikis, tagging and social bookmarking, multimedia sharing, audio blogging and podcasting, RSS, syndication and social networking (Shrivastava et al., 2011). Nicholas and Rowlands categorise them into social networking, blogging, microblogging, collaborative authoring, social tagging and bookmarking, scheduling and meeting tools, conferencing and image or video sharing (Nicholas and Rowlands, 2011).

Wikipedia lists more than 125 social networking sites, putting them into different categories (Wikipedia, 2013). Other scholars and specialists (Kassel, 2011; Anderson, 2007; Safko, 2010; Culnan et al., 2010; Digizen.org, 2014) present different categorization of social media. Al-Badi (2013) claims that he observed, over time, a kind of convergence in the proposed services. For example, the ‘gaming’ category has a number of social networking sites that might be considered as part of the ‘virtual world’ and vice versa. Similarly, Facebook, MySpace and LinkedIn can be used to promote research, innovation and collaboration between researchers as well as business managers (Al-Badi, 2013). It was clear that there are many categorizations and yet other researchers might come up with slightly different categorization.

The reason why there is no agreed categorization of social media is due to the fact that many social networking sites provide similar services that might overlap with one another. Furthermore, any new service introduced by a social media site is immediately imitated by other providers. For example “Circles” in Google+ was immediately followed by “Groups” in LinkedIn, “Networks” on Ryze, and “Lists” in Facebook. New services generate new needs for users. For example, Facebook allows users to have one list of all contacts. This worked well at the beginning but later on another need was generated in which users/customers wanted to have different lists for different purposes such as friends, family, acquaintances, following, and followers. Many social media sites compete to include more services, which makes it difficult to classify them into different categories (Al-Badi, 2013).

Benefits of Using Social Media for Government Agencies

Social media enables real two-way communication between government agencies and citizens. Therefore, the effective use of social media can help government agencies to better understand, respond to and attract the attention of target audiences, thus increasing citizen engagement, facilitating information exchange and improving governance. Generally, using social media is expected to lead to the following benefits (COI, 2011; Al-Badi, 2013):

- The ability to serve wider audiences (citizens and residents) with minimal financial input.

- The ability to reach specific audiences on specific issues.

- An increase in government access to audiences, leading to an improvement in government communication.

- The ability to be more efficient and productive in their relationships with citizens, partners and stakeholders.

- The ability to have greater scope to adjust or change communications quickly where necessary.

- An improvement in the long-term cost effectiveness of communication.

- An increase in the speed of public feedback and input.

- A reduction in government dependence on traditional media channels and a counteraction to inaccurate press coverage.

Obviously, government agencies that are looking to improve their services will surely be opting to adopt social media for the reasons mentioned above.

Obstacles in Adopting Social Media

Investigating the factors that were hindering the full-blown adoption of social media by government agencies, it was found that government agencies, especially in the Middle East, face different kinds of obstacles such as:

- Security concerns.

- Privacy concerns.

- Lack of IT infrastructure.

- Lack of a national social media strategy or plan as part of the national IT plan.

- Lack of skills among government staff.

- Concerns regarding the legal terms and conditions of using social media.

- Government censorship.

- Concerns over the integration of social networking systems with other IT solutions.

- Lack of resources to support (monitor/control and maintain, correct and update).

- Time consuming and tedious to use.

- Concerns about employee use/misuse.

- Not convinced about the value of social networking (ROI).

- Lack of accessibility.

- Challenges concerning fair and equal involvement for all citizens (digital divide) (NASCIO, 2013)

The government agencies that are opting to adopt social media in their operations need to overcome these obstacles to gain the great benefits mentioned above.

Research Methodology

In the current research, the researchers examined all available materials (i.e. journals, conference articles, official documents and online resources) regarding the usage of social media by government agencies worldwide and then classified it based on its speciality such as health, education, local government, tourism, employment, political engagement, and crises management. The classification was then downsized based on the geographical region, such as Northern America, Europe, Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA), and Eastern Asia. This literature review critically analyses and synthesizes the existing relevant research that deals with the use of social media tools by governments into common specialities such as health, education, local government, recruitment, tourism…etc.

Usage of Social Media by Government Agencies Worldwide

Several governments have seen the potential benefits of using social media; that it increases their efficiency, achieves user convenience, and enhances citizen involvement (Kuzma, 2010). Basically, the use of social media is leading to significant changes in how governments design, implement, and manage electronic services (Andersen et al., 2012). Kuzma (2010) argues that social media can be used in a variety of government settings, for example she says that specific ministries and government entities could use blogs to communicate on public hearings, wikis and RSS feeds to coordinate work, and wikis to internally share expertise and intelligence information.

Many developed countries such as the United States and United Kingdom have been advanced in this regard; they have started seriously adopting social networking to communicate with citizens, partners and stakeholders. For example, in the UK the government has implemented Tweetminster (Tweetminster, 2014), and the US government has its similar Endeavour, Tweetcongress (Tweetcongress, 2014). However, only 30% of Asian governments make full use of social media technology to communicate and disseminate information to their citizens, leading to missed opportunities to better serve their population(Kuzma, 2010). The Arab Social Media Report (ASMR), which is produced quarterly by the Dubai School of Government’s Governance and Innovation Program, reported an increase in Arab countries using social media (Mourtada and Salem, 2011).

This section outlines the different findings that show the extent to which the use of social media is widespread among different government agencies worldwide.

Social Media for Governmental Healthcare

Social media platforms can be used for many different purposes in healthcare, such as to increase compliance in the taking of medication, for patient support and health education, and to create links with patient support (Prasad, 2013). Generally, healthcare stakeholders are motivated to use social media platforms because they enhance the relationships between patients, healthcare providers, the pharmaceutical and medical device industries (Prasad, 2013). The use of social media provides a place for discussion, and a mechanism for real-time surveillance and rapid dissemination of time-sensitive health information (Harris et al., 2013). Therefore, governments worldwide have found significant potential in using social media in these various sectors. Even though governments are using social media for different purposes, they are all seeking to achieve the highest benefits with it in the health sector. The following are examples of how governments in Northern America, Europe and Eastern Asia are adopting social media in the healthcare sector:

North America

In the United States, the most popular way for the general public to seek health information is social media. For example, The World Health Organization has accounts on Facebook and Twitter, as do the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and numerous health-related schools and departments, scientists, and health-focused news outlets. CDC has developed an online toolkit to aid public health practitioners in using social media to publicize information and foster partnerships with patients (Harris et al., 2013). In addition, The Mayo Clinic has taken the initiative in advancing social media and health care. It established ‘The Mayo Clinic Centre for Social Media’, which is a unique social media centre that focuses on health care. The Mayo Clinic has one of the most popular medical provider channels on YouTube and more than 260,000 followers on Twitter, as well as an active Facebook page with more than 65,000 fans (Prasad, 2013).

Europe

In the United Kingdom, the ‘Medpedia Project’ is described as a long-term worldwide project to develop a new model for sharing and advancing knowledge about health, medicine, and the body between medical professionals and the general public. This model was founded to provide a free online technology platform that is collaborative, transparent, and interdisciplinary. Medpedia is composed of three primary components: a collaborative encyclopaedia, a network and directory for health professionals, organizations and communities of interest where medical professionals and non-professionals come together to discuss health-related topics (Prasad, 2013).

Eastern Asia

In India, a webpage named “Smoke Free India” was created on Facebook and was put under ‘Sponsored advertisement’ for 15 days, targeting the Indian population. Short messages regarding smoking and tobacco in the form of text, web links, images, and video clips were shared on the page for 30 days. This experiment revealed that a total of 907 users from different cities in India “Liked” the page; out of these 63.8% were young people aged between 13 and 17 years old (Chawada et al., 2013).

Clearly there are many attempts by different countries worldwide to benefit from using social media in healthcare. The following section sheds light on using social media by government agencies in different fields.

Social Media for Local Government

Social media can also be used in local government. Increasing the involvement of citizens online could help the government to provide the needed services for citizens and solve issues related to local government. For example, some governments use social media for educational purposes, which means that they use it for educating their constituents on a variety of topics relevant to that country (Kuzma, 2010). The following are examples of how the governments of North America and Asia are using social media in local government:

Eastern Asia and MENA

The governments of India and Kuwait have set up a site on Twitter to help prevent fatal road accidents (Kuzma, 2010)

North America

In California, the government initiated a ‘Fix my street’ application, which is a web site that enables citizens to be more active by reporting and discussing local street problems by showing them on a map with very simple instructions. This initiative makes it easier for the government to solve such problems. The website is (www.fixmystreet.com) (Zavattaro and Sementelli, 2014).

In Canada, the British Columbia Ministry of Transportation combines Mapquest data with real-time traffic data to create a ‘mash-up’ of current driving conditions and advice to drivers. Such information allows citizens to avoid crowded routes while regulating the traffic load on the main streets (Chang and Kannan, 2008).

Social Media for Governmental Education

Obviously, the main area where social networking technologies have been widely adopted is education. With the emergence of concepts such as ‘social learning’, ‘massive open online courses’ and ‘intelligent decision-making networks’, all stakeholders (i.e. educators, students and educational institutions) are increasingly relying on social media tools and technologies to create innovative approaches to education, capacity building and knowledge transfer (ASMR, 2013).

North America

NASA’s Ames Research CoLab started out as a physical collaboration facility, but soon transformed into a three-dimensional virtual online centre that allows researchers worldwide to build relationships with NASA scientists in a social network setting. The virtual centre enables contributors from around the world to participate in conferences and briefings on a more regular basis and facilitates enhanced research collaboration (Chang and Kannan, 2008).

Europe

In the United Kingdom, some public as well as private universities have adopted social media to increase their educational quality and to enhance their students’ performance. The University of Warwick student blog service was launched in October 2004. The service was the first institutional blogging service. Furthermore, the University of Newport has deployed a blogging service for its students and established a social networking environment for the student community. The Open University (OU) is an early adopter of institutional use of the Twitter micro-blogging application. Also, OU is one of the first to have a dedicated institutional page on YouTube. OU developed a number of Facebook applications. First, ‘Course Profiles’, which allows OU students to show others which courses they have studied and which ones they hope to study in the future. This application enables the student to create relationships with other OU students, leave course reviews, access free course-related content, and suggest possible future courses based on feedback from others who have studied similar things to the student. Second, “My OU Story” that allows OU students to publish their thoughts as they progress through a course. The students can assign an emotional status to each story and then see how their mood changes throughout their academic journey. The students can see other people’s stories and leave them messages, providing a means of meeting new people, offering support and sharing stories (Kelly, 2008)

Social Media for Tourism

Social media has fundamentally reshaped the way of distributing tourism-related information and the way people plan for travel. Similarly, tourists use social networking sites to portray, reconstruct and re-experience their trips (Xiang and Gretzel, 2010). This allows governments to exchange ideas using social media in order to boost tourism.

Eastern Asia

In China microblogs have become immensely popular since 2009. On August 7, 2012, the Chinese Xinhuanet reported that official government microblogs were in a stage of rapid development under the concept of ‘Microblog for all people’. It was also reported that Guangzhou City, the capital city of Guangdong Province, opened a new stage of ‘Microblog-Governance’. And Hangzhou City, the capital city of Zhejiang Province, highlighted the interaction between city, government and customers by using an official microblog in order to promote the city’s image. On January 18, 2013, the Chinese Ifeng website stated that Nanjing City, the capital city of Jiangsu Province, had integrated a microblog, microfilms and online mobile app games for city branding. Therefore, the widespread popularity of social media has resulted in more and more Chinese cities employing social media such as official city microblogs, city tourism websites, and city BBS websites, to establish city brands and promote city images. In order to satisfy the needs of urban customers and build city brand identification, social media can be considered as a valuable tool for city marketing (Zhou and Wang, 2014).

Europe

In Europe, some tourism organizations operate multiple Twitter accounts and/or Facebook pages for each regional tourism office. Spain has a general Twitter account, operated from Madrid for all audiences, and the London office has operated a general Twitter account which is geared specifically to those in the UK (Hays et al., 2012).

In Germany the German National Tourist Board used twitter to advertise The Open Air Castle Festival which was held on June 16, 2011, this being a good example of using social media to implement traditional, pre-existing marketing methods while Twitter followers of the @GermanyTourism account could easily reply to the German National Tourist Board’s tweets (Hays et al., 2012).

Similarly, Hong Kong, Israel and Macau set up tourism ministry pages. In Afghanistan, the government has set up a site on Twitter for its National Museum (Kuzma, 2010).

Social Media for recruitment and work activities

Social media has become a useful tool for recruitment and maintaining strong relationships with employees. Hrdinová, Helbig et al. (2010) mention that governments have seen an increasing number of requests by their employees to be able to use social media to do their work (Hrdinová et al., 2010). Some examples of such use of social media in studied regions are mentioned below.

North America

One example of the successful use of social media for employee recruitment was demonstrated by Spherion. Spherion is a private company which was contracted to hire employees for government agencies in the USA. Spherion used social media throughout its entire recruitment campaign, which ranged from creating a Facebook profile to posting videos on YouTube. The key to its success was overwhelming the social networking sites with entertaining and attention-grabbing ads and videos (Hrdinová et al., 2010).

There are three distinct ways in which employees are using social media while they are at work. First, employees use social media for official agency interests; for instance, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has its own YouTube channel dedicated to its activities as well as maintaining its own blogs. Second, employees use social media for professional interests; for instance, almost 30,000 government employees have signed up as members to the external site GovLoop.com to engage with other professionals in a community of practice. Additionally, employees might engage in external sites by accessing Facebook to view official government pages such as the White House Facebook page, to research information on a newly issued directive. Third, employees use social media for personal interests; for instance, employees may want to check their personal Facebook page, send out a personal tweet, or watch the latest viral YouTube video during a lunch hour or another designated break during working hours (Hrdinová et al., 2010).

Europe

The United Kingdom’s Department for Work and Pensions is piloting a social network site for UK senior citizens, with the aim of encouraging social networking among the targeted community to interact on issues related to all areas of life beyond work and pensions (Chang and Kannan, 2008).

Social Media for Political Engagement

Social media is a powerful tool that can also be used for political engagement. Governments’ adoption of social media platforms inherently increases the active involvement of citizens in government decision-making. When social media are constructed with talk-back potential, they could foster collaboration and cooperation between the government and its citizens towards achieving common goals and objectives (Zavattaro and Sementelli, 2014). In fact, social media can be used as a vehicle to enhance trust in government by increasing its openness and transparency (Abdelsalam et al., 2013). The following are examples of how governments in the Middle East, Northern Africa (MENA) and North America are using social media for political engagement.

MENA

Recent revolutions in MENA were in part attributed to the power of the Internet and, more specifically, social media platforms, and are often referred to as the Facebook revolution (Prasad, 2013). More specifically, the Egyptian revolution provides a good case study that demonstrated the impact of the adoption of social media on political transformation in government. The statistics provided in the study of Abdelsalam, Reddick et al. (2013) showed that there was a marked increase in the use of social media after the January 25th revolution. This extensive use of social media has fostered the political change in the transformation of the Egyptian government. In addition, social media has been used as an empowering tool for protesters to incite and manage political change. An activist in Cairo said: “We used Facebook to schedule the protests, Twitter to coordinate, and YouTube to tell the world” (Abdelsalam et al., 2013).

Eastern Asia

In Hong Kong, politicians are using Facebook to reach the public (Kuzma, 2010). This enables the politicians to reach as many people as they need for the election.

Europe

Iceland’s government turned towards social media technologies to crowd-source its revised constitution in order to increase citizen engagement and collaboration (Zavattaro and Sementelli, 2014).

North America

In the U.S., as part of the 2006 national election, Facebook created entries for all US congressional and gubernatorial candidates, and users could express their support for candidates. Users’ level of support had a significant effect on the final vote shares, especially for open-seat candidates (Kuzma, 2010).

Recently, social media technologies have become acceptable information and communication channels in the U.S. federal government. After an initial informal experimentation period, a presidential directive, the “Open Government Initiative”, focused the speed and direction of the use of social media applications among the executive departments of the U.S. federal government (Mergel, 2013). For example, the State Department has initiated a campaign called “Ask State” via Twitter. This initiative mirrors the shift in public administration towards governance through networking rather than following only the top—down government interventions (Zavattaro and Sementelli, 2014).

One example that focuses on the collaboration of social media applied in the government agencies is the use of Google Plus and Facebook to hold the digital town hall meetings with Obama. Another successful use of social media is the civically engaged use of Wiki technologies at various levels of government. Moreover, citizens’ engagement via social media enables them to create new opportunities to become far more involved in defining accountability, developing solutions and analysing data via ever-evolving social media tools (Zavattaro and Sementelli, 2014)

In the City of Iowa, the city’s social media policy emphasizes that the city’s website will remain the city’s main Internet presence. Additionally, in Arlington Texas’s policy indicates that social media users should be directed back to the city’s official website when possible. While comments might be made on social network such as Google Plus and Facebook, there might not be engagement and collaboration taking place on such sites. Thus, there is expanded capacity for interaction between government and citizens but not necessarily collaboration (Zavattaro and Sementelli, 2014)

Spartanburg County, South Carolina, and the town of Cary, North Carolina, have undertaken initiatives to use social media at the local government level, which clearly highlights the potential for social computing in the enhancement of constituents’ and citizens’ engagement (Chang and Kannan, 2008).

Representing a step forward in the combination of governance and IT, President Barack Obama’s administration has pursued a range of open initiatives guided by the principles of transparent, participatory, and collaborative leadership (Bertot et al., 2010b). To further foster openness, the administration issued the Open Government Directive (Executive Office, 2009), which requires agencies to issue and implement open government plans, among other key initiatives (Bertot and Jaeger, 2010).

Nowadays many government agencies are developing and expanding their online presence via social media technologies. Depending on mission and goals, several agencies are using social media such as Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, and YouTube for various purposes (Bertot and Jaeger, 2010). The following are examples of the presence of federal agencies on YouTube, which include lectures and tutorials, descriptions of agency services, public service announcements, instructions on how to use agency content, and recent events (Bertot and Jaeger, 2010):

- General Services Administration(USA.gov, 2015)

- White House(White House, 2015)

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa, 2015)

- Centres for Disease Control (CDC, 2015)

- Department of State(USDeptOfState, 2015)

- Department of Health and Human Services (USGOVHHS, 2015)

- Census Bureau (uscensusbureau, 2015)

Moreover, new ways of accessing and disseminating government information, services, and resources are created by several other agencies via social media (Bertot and Jaeger, 2010), for example:

- The Veterans Administration established a presence to interact with veterans on Facebook (DeptVetAffairs, 2015a), YouTube (DeptVetAffairs, 2015c), Flickr (DeptVetAffairs, 2015b), and Twitter (www.twitter.com/DeptVet Affairs).

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) created an ocean explorer site (NOAA, 2015a) to allow users to explore and learn about the sea. NOAA also created an ocean explorer channel on YouTube to allow greater accessibility to its vast content (NOAA, 2015b).

- The General Services Administration uses a variety of social media technologies, including Facebook (USA.gov, 2015) and YouTube (USA.gov, 2015), to help people learn about and access government services.

- gov not only takes advantage of a range of social media technologies but also tries to merge resources and benefits across a wide range of ‘critical need’ areas such as employment, transportation, education, and health.

- The Federal Register site (FedReq, 2015), which was created by the US National Archives and Records Administration, makes the contents of the Federal Register more interactive and accessible.

Social Media for Crisis Management

Governments have successfully used social media to keep members of the public informed in the case of natural disasters (Kuzma, 2010). More recently social media platforms have been playing a remarkable and transformative role in the way society responds to mass emergencies and disaster (Dabner, 2012). The following examples demonstrate the use of social media in crises and disasters in North America, Eastern Asia, the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA).

North America

In the U.S., an examination of Weblogs (blogs) was conducted after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, which revealed that these blogs had four functions: communication, political, information and helping. Additionally, they helped maintain a sense of community in the crisis.

In California, during the October 2007 Southern California wildfires, local government used social networking sites and other backchannel communications to update the community about the situation and to more effectively manage the disaster response (Kuzma, 2010).

Eastern Asia

In China, a large community of people used social media as a platform for sharing information, opinions, action-related assistance and emotional support after the Sichuan earthquake in 2008 (Dabner, 2012).

MENA

In Iraq, social media played an important role in helping people adapt to work and social life when faced with continued disruption to their physical environment (Dabner, 2012).

Conclusion

This study aims to investigate the adoption of social media in government agencies/departments because, as Chang and Kannan claim, government agencies need to meet citizens where they are, online, because young citizens are now engaging in the use of online social media (Chang and Kannan, 2008). This study was based on published material (i.e. journals and conferences articles, online resources etc.).

The findings of this research show that many countries are still hesitant in adopting social media, and most efforts made in these countries are individual efforts (i.e. efforts by individuals working in government agencies but which are not institutionalised) and there are no collective efforts between different government agencies. The reason why many of these countries have yet to adopt social media is because they are facing critical technical, financial and political challenges in adopting it, especially in developing countries.

Many other countries have either started using social networking effectively or are in the stage of preparing to do so. The study highlights that the countries using social media are mostly developed countries and they are using it in four main areas: tourism, education, health and foreign affairs. The majority of countries worldwide have started building strategies to adopt such media, and some of them already have guidelines in place for adopting social media in government departments.

As it is important for government agencies/departments to create and maintain a strategic presence on social media, the researchers would encourage the government agencies/departments of developing countries to start the process of adopting social media quickly by configuring what is needed to jump on the social media bandwagon and start taking advantage of such technological advancements. To start reaping the benefits of using social media, the following needs to be done:

- Explore how other developed countries are utilizing it to achieve better public engagement with citizens, to aid organizational strategy-building and improve decision making.

- Put in place the policies/guidelines that ensure smooth adoption. In this regard, many issues need to be dealt with, such as:

- Security and confidentiality issues, such as how private information owned by different citizens/residents as well as government agencies would be protected.

- Who should represent the agency/department in responding to queries and how controversial issues would be dealt with?

- What would be the relationship between what is shown on the government agency’s website and what is shown on the different social media sites?

- Which social media should be adopted?

- Where to meet different categories of citizens/residents i.e. on which social media sites?

3.Government, especially in the developing countries, needs to work around the different obstacles that are hindering the quick adoption of social media. These countries need not be hesitant or afraid of doing so as this technology is here to stay. This effort might include:

- Providing the funding for acquiring the needed skills and tools.

- Training programmes and workshops, which should be conducted for the public to enhance their IT/social media literacy

- Supporting the interconnection of government agencies, thus simplifying information access

- Marketing existing social media sites to encourage citizens and residents to take advantage of the services provided

- Building the IT skills of government agencies/departments staff to encourage them to accept the concept of using social media to better satisfy citizens/residents.

- Encouraging government agencies/departments to modify their internal procedures to make better use of social media sites.

As this study is merely based on the published material (i.e. journals and conferences articles, online resources etc.), researchers were not able to verify how the current adopters of social media are managing its usage, and what tools they are using to monitor/analyse the interaction with the citizens/residents. Also, the study did not go on to explore what guidelines/policies are in use by the current adopters of social media.

However, as this study is part of another major study titled: “Creating a Strategic Presence in Social Media: A Framework for the Utilization of Social Media by Government Agencies in Oman”, all these issues are going to be dealt with. In this regard, a netnography analysis, field visits, and focus group are going to be conducted very soon.

References

- Abdelsalam, H. M., Reddick, C. G., Gamal, S. and Al-shaar, A., (2013), Social media in Egyptian government websites: Presence, usage, and effectiveness, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 30 (4), pp. 406-416.

- Al-Badi, A. H., (2013), The adoption of social media in government agencies: Gulf Cooperation Council case study, Journal of Technology Research, vol. 5 (2013), pp. 1-26.

- Al-Qassemi, S. S., (2012), Gulf Governments Take to Social Media, Accessed on 16/04/2012, Available at: [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/sultan-sooud-alqassemi/gulf-governments-take-to-_b_868815.html]

- Ammari, S. S., (2012), GCC governments ready to embrace social media, Accessed on 31/07/2014, Available at: [http://www.euroasiaindustry.com/article/gcc-governments-ready-to-embrace-social-media]

- Andersen, K. N., Medaglia, R. and Henriksen, H. Z., (2012), Social media in public health care: Impact domain propositions, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 29 (4), pp. 462-469.

- Anderson, P., (2007), What is Web 2.0? Ideas, Technologies and Implementation for Education, JISC Technology and Standards Watch, vol. Feb. 2007, pp. 1-64.

- ASMR, (2013), Transforming Education in the Arab World: Breaking Barriers in the Age of Social Learning, Accessed on 23/07/2014, Available at: [ArabSocialMediaReport.com]

- Bard, M., (2010), 15 Categories of Social Media, available Accessed on 24/07/2014, Available at: [http://www.mirnabard.com/2010/02/15-categories-of-social-media/]

- Bertot, J. C. and Jaeger, P. T., (2010), Social Media Technology and Government Transparency, University of Maryland.

- Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T. and Grimes, J. M., (2010a), Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 27 (3), pp. 264-271.

- Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T. and Grimes, J. M., (2012a), Promoting transparency and accountability through ICTs, social media, and collaborative e-government, Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, vol. 6 (1), pp. 78-91.

- Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T. and Hansen, D., (2012b), The impact of polices on government social media usage: Issues, challenges, and recommendations, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 29 (1), pp. 30-40.

- Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., Munson, S. and Glaisyer, T., (2010b), Social Media Technology and Government Transparency, Computer, vol. 43 (11).

- Boyd, D. (2008), Why youth (heart) social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life, In The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning(Ed, Buckingham, D.) The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 119-142.

- CDC, (2015), Centres for Disease Control Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [http://www.youtube.com/user/CDCStreamingHealth]

- Chang, A.-M. and Kannan, P. (2008), Leveraging Web 2.0 in government, IBM Center for the Business of Government.

- Charron, C., Favier, J. and Li, C., (2006), Social computing: How networks erode institutional power, and what to do about it, Accessed on 14/11/2011, Available at: [http://www.forrester.com/rb/Research/social_computing/q/id/38772/t/2]

- Chawada, B., Kadia, A., Kosambiya, J. and Kantharia, S., (2013), Social Networking Media: Going One Step Ahead for Smoking Awareness and IEC, vol. 4 (4).

- Cohen, H., (2011), 30 Social Media Definitions, Accessed on 24/07/2014, Available at: [http://heidicohen.com/social-media-definition/]

- COI, (2011), Online Social Networks – Research Report, Accessed on 24/07/2014, Available at: [http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120919132719/http://www.communities.gov.uk/publications/communities/onlinesocialnetworks]

- gov.uk, (2008), Online Social Networks – Research Report, Accessed on 14/11/2011, Available at: [http://www.communities.gov.uk/publications/communities/onlinesocialnetworks]

- Culnan, M. J., McHugh, P. J. and Zubillaga, J. I., (2010), How large US companies can use Twitter and other social media to gain business value, MIS Quarterly Executive, vol. 9 (4), pp. 243-259.

- Dabner, N., (2012), ‘Breaking Ground’in the use of social media: A case study of a university earthquake response to inform educational design with Facebook, The Internet and Higher Education, vol. 15 (1), pp. 69-78.

- Dadashzadeh, M., (2010), Social media in government: From eGovernment to eGovernance, Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), vol. 8 (11).

- DeptVetAffairs, (2015a), S. Department of Veterans Affairs:Facebook, Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [https://www.facebook.com/VeteransAffairs]

- DeptVetAffairs, (2015b), S. Department of Veterans Affairs:flickr, Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [https://www.flickr.com/photos/44636446@N04]

- DeptVetAffairs, (2015c), S. Department of Veterans Affairs:youtube, Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [http://www.youtube.com/user/DeptVetAffairs]

- gov, (2014), Social Media, Accessed on 31/07/2014, Available at: [http://www.digitalgov.gov/category/socialmedia/]

- DigitalLikeness, (2008), The difference between social media and social networking, Accessed on 24/07/2014, Available at: [http://www.afhill.com/blog/the-difference-between-social-media-and-social-networking/]

- org, (2014), Digizen website Accessed on 01/08/2014, Available at: [http://digizen.org/]

- Effing, R., van Hillegersberg, J. and Huibers, T. (2011), Social media and political participation: are Facebook, Twitter and YouTube democratizing our political systems?, In Electronic participationSpringer, pp. 25-35.

- Executive Office (2009), Open Government Directive, Executive Office of the President, Washington, D.C. 20503.

- Eyrich, N., Padman, M. L. and Sweetser, K. D., (2008), PR practitioners’ use of social media tools and communication technology, Public relations review, vol. 34 (4), pp. 412-414.

- FedReq, (2015), Federal Register, Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [https://federalregister.gov/]

- Golbeck, J., Grimes, J. M. and Rogers, A., (2010), Twitter use by the US Congress, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 61 (8), pp. 1612-1621.

- Harper, L., (2013), Gov 2.0 Rises to the Next Level: Open Data in Action, Accessed on 18/04/2015, Available at: [http://opensource.com/government/13/3/future-gov-20]

- Harris, J. K., Mueller, N. L. and Snider, D., (2013), Social media adoption in local health departments nationwide, American journal of public health, vol. 103 (9), pp. 1700-1707.

- Hays, S., Page, S. J. and Buhalis, D., (2012), Social media as a destination marketing tool: its use by national tourism organisations, Current Issues in Tourism, vol. 16 (3), pp. 211-239.

- Hilgers, D. and Piller, F., (2011), A government 2.0: fostering public sector rethinking by open innovation, Innovation Management, vol. 1 (2), pp. 1-8.

- Howard, A., (2013), Making Dollars and Sense of the Open Data Economy, Accessed on 18/04/2015, Available at: [http://radar.oreilly.com/2012/12/making-dollars-and-sense-of-the-open-data-economy.html]

- Hrdinová, J., Helbig, N. and Peters, C. S. (2010), Designing social media policy for government: Eight essential elements, Center for Technology in Government, University at Albany.

- Jaeger, P. T., Bertot, J. C. and Shilton, K. (2012), Information Policy and Social Media: Framing Government–Citizen Web 2.0 Interactions, In Web 2.0 Technologies and Democratic GovernanceSpringer, pp. 11-25.

- John C. Bertot, Paul T. Jaeger and Grimes, J. M., (2010), Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies, Government Information Quarterly 27.

- John Carlo Bertot, Paul T Jaeger, Sean Munson and Glaisyer, T., (2010), Social media technology and government transparency, Computer, vol. 43 (11), pp. 53-59.

- Kaplan, A. M. and Haenlein, M., (2010), Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media, Business Horizons, vol. 53 (1), pp. 59-68.

- Kassel, A., (2011), Social Networking: A Research Tool, Accessed on 18/3/2013, Available at: [http://web.fumsi.com/go/article/find/3196]

- Kelly, B., (2008), A review of current and developing international practice in the use of social networking (Web 2.0) in higher education.

- Kietzmann, J. H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I. P. and Silvestre, B. S., (2011), Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media, Business Horizons, vol. 54 (3), pp. 241-251.

- Kuzma, J., (2010), Asian government usage of Web 2.0 social media, European Journal of ePractice, vol. 2010 (9), pp. 1-13.

- Lawati, A. A., (2011), Report throws light on social-media usage in Arab world, Accessed on 4/2/2012, Available at: [http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/uae/media/report-throws-light-on-social-media-usage-in-arab-world-1.818741]

- Lazer, D., Pentland, A. S., Adamic, L., Aral, S., Barabasi, A. L., Brewer, D., Christakis, N., Contractor, N., Fowler, J. and Gutmann, M., (2009), Life in the network: the coming age of computational social science, Science (New York, NY), vol. 323 (5915), pp. 721.

- Mergel, I., (2013), Social media adoption and resulting tactics in the US federal government, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 30 (2), pp. 123-130.

- Mourtada, R. and Salem, F., (2011), Facebook Usage: Factors and Analysis, Arab Social Media Reoprt, vol. 1 (1).

- Nasa, (2015), National Aeronautics and Space Administration Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [http://www.youtube.com/user/NASAtelevision]

- NASCIO, (2013), A National Survey of Social Media Use in State Government: Friends, Followers, and Feeds, Accessed on 24/07/2014, Available at: [http://www.nascio.org/publications/documents/NASCIO-SocialMedia.pdf]

- Nicholas, D. and Rowlands, I., (2011), Social media use in the research workflow, Information Services and Use, vol. 31 (1-2), pp. 61-83.

- NOAA, (2015a), The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA):, Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/]

- NOAA, (2015b), The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA):youtube, Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [http://www.youtube.com/oceanexplorergov]

- O’Reilly, T., (2009), Gov 2.0: It’s All About The Platform, Accessed on 18/04/2015, Available at: [http://techcrunch.com/2009/09/04/gov-20-its-all-about-the-platform/]

- Picazo-Vela, S., Gutiérrez-Martinez, I. and Luna-Reyes, L. F., (2011), Social media in the public sector: perceived benefits, costs and strategic alternatives, In the proceeding of Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Digital Government Research Conference: Digital Government Innovation in Challenging Times, 198-203

- Picazo-Vela, S., Gutiérrez-Martínez, I. and Luna-Reyes, L. F., (2012), Understanding risks, benefits, and strategic alternatives of social media applications in the public sector, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 29 (4), pp. 504-511.

- Prasad, B., (2013), Social media, health care, and social networking, Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, vol. 77 (3), pp. 492-495.

- Rey, P., (2011), Recap: Social Media and Egypt’s Revolution, Accessed on 31/07/2014, Available at: [http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2011/02/16/recap-social-media-and-egypt/]

- Safko, L. (2010), The social media bible: tactics, tools, and strategies for business success,

- Shrivastava, M., Paperwala, T. and Dave, k., (2011), Trends in Web Technologies: Web 1.0 to Web 3.0 & Beyond, The International Information Systems Conference (iiSC2011).

- SocialMediaToday, (2010), 5 Differences between Social Media and social networking, Accessed on 24/208/2014, Available at: [http://www.socialmediatoday.com/SMC/194754]

- Tweetcongress, (2014), Tweetcongress, Accessed on 01/08/2014, Available at: [http://www.tweetcongress.org/]

- Tweetminster, (2014), Tweetminster, Accessed on 01/08/2014, Available at: [http://www.tweetminster.co.uk/]

- Unsworth, K., Axelsson, A.-S., Goggins, S. and Mascaro, C., (2012), Exercising Control: A Comparative Study of Government Agencies and their Relationships with the Public Using Social Media, In the proceeding of The 13th Annual International and Interdisciplinary Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers (AoIR), MediaCity: UK, University of Salford, 18-21

- gov, (2015), General Services Administration, Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [ Http://www.youtube.com/USGovernment]

- uscensusbureau, (2015), Census Bureau Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [http://www.youtube.com/user/uscensusbureau]

- USDeptOfState, (2015), Department of State, Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [http://www.youtube.com/user/statevideo]

- USGOVHHS, (2015), Department of Health and Human Services Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [http://www.youtube.com/user/USGOVHHS]

- White House, (2015), White House Accessed on 24/1/2015, Available at: [youtube.com/user/whitehouse]

- Wigand, F. D. L. (2011), Gov 2.0 and Beyond: Using Social Media for Transparency, Participation and Collaboration, In Networked Digital TechnologiesSpringer, pp. 307-318.

- Wikipedia, (2013), List of social networking websites, Accessed on 18/3/2013, Available at: [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_social_networking_websites]

- Xiang, Z. and Gretzel, U., (2010), Role of social media in online travel information search, Tourism management, vol. 31 (2), pp. 179-188.

- Zavattaro, S. M. and Sementelli, A. J., (2014), A critical examination of social media adoption in government: Introducing omnipresence, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 31 (2), pp. 257-264.

- Zhou, L. and Wang, T., (2014), Social media: A new vehicle for city marketing in China, Cities, vol. 37, pp. 27-32.