Introduction

Organizations’ environment is changing rapidly, also forcing them to change in order to survive. But surviving is not enough, because capitalism rewards the adaptable and the efficient (Gilpin, 2000) and organizations are craving for growth. All enterprises go through change, but there are some which “proactively opt to change to take advantage of new growth and opportunities”, while others “are forced to quickly change to survive and remain competitive” (PMI, 2014, p. 13).

The rate of change has been accelerating in the last decades, because of the increasing value of information, technological advances, economic globalization, pressure on resources, population ageing, diminishing markets’ regulations and so on. Changing environment has been even more virulent, starting with 2008, since “Europe has been suffering the effects of the most severe economic crisis it has seen in 50 years: for the first time in Europe there are over 25 million unemployed and in the majority of member states small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have not yet been able to bounce back to their pre-crisis levels” (European Commission, 2013, p. 3).

The 2008 financial crisis, followed by a strong economic recession, had various long-term effects on individuals and organizations – increasing debts, high bankruptcy and unemployment rates, inflation, rising prices, constricting austerity programs etc., all these leading to a highly turbulent environmental change, which makes it even more difficult for entrepreneurs to fully understand or predict the outcome of economic phenomena.

Although not all market sectors are experiencing change to the same extent, change management is a useful tool for all entrepreneurs in this complex dynamic of economic systems, where chaos and order are coexisting (Abraham, Rempel and Rogers, 2006). While “automotive, IT, telecom and utilities report above-average susceptibility to change” (Project Management Institute – PMI, 2013) and use more frequently change management instruments, other market sectors are less open to organizational change management. Resistance to change management is reducing over time – the percentage of companies using specific methodology raised from 34% in 2003 to 79% in 2013 (Prosci, 2014). Also, studies prove that change management is saving money, constitutes an important competitive advantage (PMI, 2014) and that there is a high correlation between project’s success and change management effectiveness (Prosci, 2014).

Because of the financial crisis and economic recession, “Europe faces a moment of transformation” (European Commission, 2010, p. 5), when change can be beneficial, or not, to entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship plays an important role in its economic growth, contributing substantially to income, output and employment (Edinburg Group, 2013), and even getting involved in solving social problems. In the EU, 99.8% of existing companies are small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs); they provide jobs for 88.8 million people, generating 58.2% of the added value and 28% of GDP (European Commission, 2014). This is happening even though “entrepreneurs in Europe find themselves in a tough environment: education does not offer the right foundation for an entrepreneurial career, difficult access to credits and markets, difficulty in transferring business, the fear of punitive sanctions in case of failure, and burdensome administrative procedures” (European Commission, 2013, p. 3). In Romania, SMEs have a lower contribution to the national added value than the average in the EU (49.9% reported to 58.2% at EU28 level), mainly because of the low density of SMEs reported to the number of population. Still, according to the Romanian National Statistic Institute (2014), SMEs represent 80% of existing companies and they realized 57.9% of the enterprises’ total turnover in 2012.

Considering the accelerating rate of change, the present organizational volatile environment determined by economic recession and SMEs important contribution to economic growth, in spite of the specific obstacles they are facing, change management proves itself as being a critical skill for Romanian and European entrepreneurs affected by the economic recession.

Entrepreneurship in EU and Romania

Entrepreneurship is considered a booster for economic growth and a core objective of European Union, this being reflected in its multiple efforts to create the proper climate for entrepreneurs: Lisbon European Council in 2000, the Green Paper on “Entrepreneurship in Europe” in 2003, Europe 2020 Strategy in 2010, Small business Act in 2008 (upgraded in 2011), Industrial Policy Communication in 2012, the support of European Social Fund for entrepreneurs through its financial and business support services etc.

Starting as SMEs, entrepreneurs usually confront peculiar obstacles: lack of managerial and technical skills (Rahman and Ramos, 2010); organizational and cultural issues regarding “venturing, customer involvement, external networking, research and development (R&D) outsourcing, and external participations” (Van de Vrande et al., 2009); comparative with US SMEs, European SMEs face lower productivity, growth capacity and employment rate by their seventh year, more difficulties in accessing finance, less innovating capabilities comparative to larger enterprises, frequent lack of management and technical skills, rigidities in labor markets at the national level, unawareness of existing opportunities, discouraging public authorities’ procedures etc. (European Commission, 2008). But, SMEs, also, have strengths helping them to succeed: their adaptability, lack of bureaucracy and willingness to take risks (Parida et al., 2012).

Entrepreneurs are social actors, influenced by the social, economic and political context (Uzunidis, Boutillier and Laperche, 2014), who undertake “concrete actions in terms of initiating and performing activities related to new venture creation” (Bayon, Vaillant and Lafuente, 2015). Europeans consider (European Commission, 2012) that entrepreneurs are job creators (87%) and products’ and services’ creators (79%).

By definition, an entrepreneur takes action towards initiating change. Whether it is the initial decision to become an entrepreneur or one of many decisions following, change is a part of an entrepreneur’s life. Analyzing different business growing models (Fischer, 2006; Churchill and Lewis, 1883; Nolan, 1979), we identified four main stages of development, with specific challenges predisposing to change (Table 1).

Table 1: Challenges generating change during business growth process

Source: Adapted and restructured from Fischer, 2006; Churchill and Lewis, 1883; Nolan, 1979.

As seen in the table above, entrepreneurs have to be prepared to cope with various changes. Their ability to adapt helps them to decide to be self-employed in the first place, in spite of the risks implied, and helps them now to overcome the challenges of their enterprise growth, and even to transform the failure into an asset, through accumulated experience.

Considering the risks, only 37% Europeans would rather be self-employed, while 58% would prefer to work as employees. There are three EU Member States where a majority of respondents say that self-employment is desirable: Romania (58%), Bulgaria (58%), and Latvia (55%). Regarding entrepreneurship in Romania, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Nagy et al., 2013) is reporting that Romanians are “confident about their skills to start a new business” (48%) and “their ability to identify business opportunities” (32%), that “the proportion of those involved in any kind of entrepreneurial activity in Romania has increased in the last three years” and that the level of total early-stage entrepreneurship activity (TEA) “is one of the highest in the Central and Eastern Europe region” (11.3%).

Romania is one of the Eastern European states that have experienced a period of profound structural change, while also facing a significant population decline. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Nagy et al., 2013) offers some insights on the Romanian economy and environmental conditions for entrepreneurs: after decreasing between 2008 and 2010, GDP started to increase, while inflation rate decreased in 2013 by 1.6%.

Romanian legislation has been adapted over the years to the international regulations, in order to reduce barriers in SMEs establishment and challenges in their activity. Still, the main barriers to self-employment perceived by Romanians are lack of capital (48%) and the complexity of administrative process (36%) (European Commission, 2012), as well as cumbersome regulations and high taxes, limited entrepreneurial education at primary and secondary level, and availability of financial resources (Nagy et al., 2013).

Entrepreneurs are facing peculiar obstacles and continuous change, originating in their environment or in their business growth process. Approaching change in a structured manner can diminish the risks associated with these and change management is offering the necessary tools to do this.

The impact of economic crisis and recession on Romanian industries

Since 2008, when the financial and economic crisis started, economies have been threatened, austerity measures have been applied, social movements arisen, and „almost all governments engaged in substantial deficit spending to inject liquidity into financial markets and to fight the economic downswing” (Schneider and Kirchgässner, 2009, p. 319). Even the general laws of capitalism have been discussed, Acemoglu and Robinson (2015, p. 3) arguing that Marx and Piketty (2014) ignored „key forces shaping how an economy functions: the endogenous evolution of technology and of the institutions and the political equilibrium that influences not only technology but also how markets function and how the gains from various different economic arrangements are distributed”.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the impact of the economic crisis and recession on Romanian industries, during 2008-2013, a period characterized by a volatile organizational environment and high pressure, especially for SMEs. The used model is based on the assumption that in a turbulent environment/period the dispersion of performance indicators is higher for particular industries, while a lower dispersion is evidence of economic stability and managerial congruence.

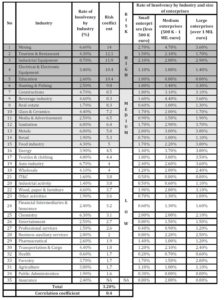

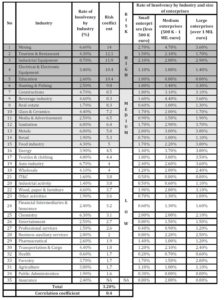

A Risk Coefficient has been calculated, based on variation coefficients of eight critical indicators – weighted according to their level of importance – for 37,593 top companies, from 182 sub-industries grouped in 35 industries, containing both private and public organizations. The Risk Coefficient has been estimated starting from the following indicators: variation coefficients of Turnover (2013 vs. 2012 and 2013 vs. 2008), variation coefficient of Employee number (2013 vs. 2008), variation coefficients of Net profit margin (2013 and 2008-2013), variation coefficients of Receivables turnover (2013 and 2008-2013), and variation coefficient of Inventory turnover (2008-2013). Furthermore, in order to verify the model’s validity, it has been estimated the correlation between the resulted Risk Coefficient for each industry and insolvencies registered in that sector for the analyzed period (Table 3); the resulted correlation coefficient was 0.4, proving that there is a direct, positive and significant correlation between the two.

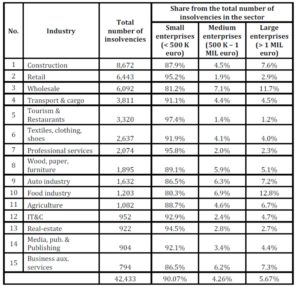

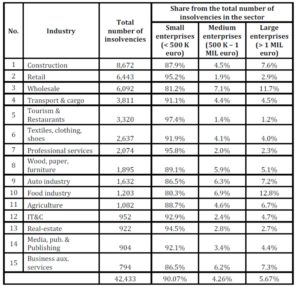

Based on the financial statements submitted by companies during 2008-2013, it has been established a ranking of main industries by the number of insolvencies (Table 2), differentiating between small, medium and large enterprises (in terms of turnover). As expected, Construction, Retail and Wholesale occupied the first positions in the top regarding insolvencies during the five post-crisis years. It can be noticed that small enterprises have been the most injured by the recession, constituting 90.07% of insolvent enterprises and ranging from 80.3% (Food industry) to 97.4% (Tourism and restaurants). These have been followed by large enterprises, constituting 5.67% of insolvent enterprises and ranging from 1.2% (Tourism and restaurants) to 12.8% (Food industry), and medium enterprises, which handled better the crisis, constituting only 4.26% on Romanian enterprises, ranging from 1.4% (Tourism and restaurants) to 7.1% (Wholesale).

Table 2: Top 15 industries based on the number of insolvencies (2008-2013)

The total number of insolvencies for each industry is a result of general economic conditions, industry’s particular context and management teams’ performance. Tourism and restaurants was the most affected at small enterprises level, but at medium and large enterprises level, this industry has been placed 15th in the Top of insolvencies. While in small companies, Tourism, Professional services and Retail had a higher level of insolvencies, in medium and large enterprises, Wholesale and Food industry, followed by Auto (in medium enterprises) and Constructions (in large enterprises) had the higher risk, suggesting that there are different “hot spots” in different economic sectors.

Moreover, segmenting small enterprises in those with a turnover under 100 k euros and those with a turnover of 100 – 500 k euros, we came to a very interesting finding. Companies having the turnover under 100 k euros registered a level of insolvency below the general average in their sector (except 3 out of 35), while companies with a turnover of 100 – 500 k euros are, generally, positioned above average. Therefore, we can state that small enterprises with a turnover between 100,000-500,000 euros are more affected by the current turbulent business environment, facing important challenges for their managers. Rates of insolvency (number of insolvencies / number of active companies), per industry and companies’ size, are illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3: The Risk Coefficient correlated with level of Insolvency

As already stated, the positive correlation (0.4) between generated Risk Coefficient and Romanian enterprises’ rate of insolvency (by industry) certifies the model’s validity and results. The study’s results show that small enterprises, especially the ones having turnover of 100,000-500,000 euros, need the most to be efficient in change management, in the Economic Recession context. Mining and Education, also, find themselves in a very risky situation, although they benefit of protectionist regulations, even for private organizations, change is much needed in these fields.

Regarding the Risk Coefficient values, we suggest that in industries with the highest distribution of model’s ratios, there are significant differences between organizations regarding:

• managerial skills available to the organizations;

• level of understanding of industry’s change (in general), and direct competition’s evolution (in particular);

• level of adjustment to the current business environment and/or to the specific sector where they are activating;

• other factors influencing the level of performance in the industry.

In this context, the industries showing the largest variation for analyzed indicators are the sectors with the highest business risk and the highest need for change. To simplify, we believe that change can be achieved on following two segments:

• from less advantageous area to average area: companies need to improve their activity, raising their performance indicators towards sector’s average;

• from average area to most advantageous area: companies need to take advantage of the opportunities available on the industry, in order to achieve exceptional results, just as their competitors with excellent results.

Change Management benefits for enterprises affected by economic recession

Change management is “a process of communicating and enforcing a program consisting of clearly defined, time-framed actions an organization needed to take from an undesirable state A to a desirable state B, with both states being clearly defined and measurable” (Taher et al., 2012, p. 347).

The first theoretical papers on organizational change management were published in the ‘50s, but its recognition, conceptualization and implementation started in the ‘80s in private companies in the USA (Prosci Inc., 2013). This way, organizational change began to be managed as a distinct process, capitalizing on a structured and efficient approach, with specific methodologies and instruments.

Since 2000, change management has been widely accepted, becoming a necessary ability for managers and leaders, as well as for entrepreneurs. According to a study carried out in 2014, on a sample of over 800 companies from all over the world, the use of change management methodologies has increased from 34% in 2003 up to 79% in 2013 (Prosci Inc., 2014), its wide implementation proving its high efficiency.

Properly used, change management is helping the organization to adapt to its environment and to achieve its objectives. Project Management Institute (2014, p. 4) shows that only 18% organizations successfully manage strategic change initiatives “to keep up with the volatile global economy”. In these companies, “twice as many strategic initiatives meet original goals and are completed on time and on budget” – compared to the companies less effective in change management (p. 7); also, “83 percent of them indicate a strong financial condition compared to just 52 percent of their less effective counterparts” (p. 8).

Change management implementation bears numerous benefits, for all organizations, regardless of their size and lifecycle:

• Facilitates a high understanding of needed change and the way it is possible;

• Offers the instruments to adapt to the present volatile business environment: financial, technological and legislative developments, consumers’ needs and requests, competitors aggressive strategies etc.;

• Makes possible the success of strategic initiatives, which always involve change;

• Increases the effectiveness of organizational projects, by meeting and exceeding objectives, staying on schedule and budget (Prosci, 2014);

• Reduces financial loss – “organizations lose US$109 million for every US$1 billion invested in all projects, due to poor project performance” (PMI, 2014, p. 4);

• Helps enterprises becoming financially stronger;

• Prepares people for change, reducing their resistance;

• Reduces risks associated with change.

Although all organizations are experimenting change, and therefore need change management capabilities, there are some for which change management is critical in order to survive: small and medium enterprises, especially those from industries highly affected by economic recession, as seen in the previous section. SMEs’ activity has specific characteristics and face specific obstacles, determining a higher need for change management capabilities:

• For smaller organizations, the effects of the environment dynamism and complexity seems to be even stronger (Busenitz and Barney, 1997), facing a more hostile or uncertain environment (Hambrick and Crozier, 1985; Covin and Slevin, 1989); change management proved itself very useful in such environment;

• Unlike managers in large firms, entrepreneurs do not have access to extensive information sources (Gibcus, Vermeulen and de Jong, 2009), which makes change more hazardous; entrepreneurs need external advice and information regarding business environment and change management, in order to diminish the risks;

• In small enterprises there is less room for political decisions, with multiple actors and their conflicting goals, since the entrepreneur makes the decisions individually, as a single authoritarian individual, as in the rational model (Gibcus, Vermeulen and de Jong, 2009); hence, the importance of entrepreneur’s formal change management training and his readiness to foster change;

• Entrepreneurs are “decisive, impatient, action oriented individuals” (Smith et al., 1988: 224), favor individualism, do not mind taking risks, are not egalitarians and are more motivated to make money (McGrath et al., 1992); in order to have a structured change management approach, entrepreneurs might hire an external change agent, diminishing this way the costs implied by developing specific internal capabilities;

• SMEs, being less prosperous and innovative than large enterprises (Romanian National Statistic Institute, 2014; Commission of the European Communities, 2008), do not afford the general 70% rate of failure in change initiatives (Keller and Aiken, 2009; Kotter, 1995);

• Difficult access of SMEs to finance and discouraging public procedures (Commission of the European Communities, 2008) are real obstacles in implementing change efficiently.

Entrepreneurs have a critical role in change management implementation, because owners and employees perceive change differently: while entrepreneurs “see change as an opportunity for both the business and themselves”, “employees typically see change as disruptive, intrusive and likely to involve loss” (PMI, 2014, p.9). In order to favor the success of the change initiative, entrepreneurs should have a profound understanding of change and their role in it, should have management and leadership skills, manifest active and visible executive sponsorship for change process, have a strategic perspective on organizational development and formal change management training, have communication and coaching skills, demonstrate support and enthusiasm for the change, manage resistance, and provide support to the change project team.

Contributions and limits

The contribution of this paper resides in the identification of the main challenges faced by local entrepreneurs in different development stages of their companies, indicating the economic sectors in special need of change management’s implementation, in order to achieve sustainable performance. Prioritizing “hot”, risky industries is a new and much needed insight regarding Romanian entrepreneurial arena. This process is reflecting the market’s specific challenges in the national post-crisis business environment. The study’s results can create awareness regarding business risks and their impact on organizations, which can influence business owners’ and managers’ to focus on their markets’ specifics and to allocate a higher amount of resources for change management.

Nevertheless, from an academic perspective, further research on the matter is recommended. An extension of the research may be achieved by extending the base of the analysis (a higher number of analyzed companies and a longer timeline – to improve the accuracy of our model) and also by identifying new key variables for evaluating economic performance. These adjustments will contribute to the model’s enhancement and calibration.

Practitioners will find particularly useful a further exploration realized by: a deep-dive at sub-industry level or working on cluster analysis on connected or similar industries; collection of insights and results of surveys on top managers of companies from our identified groups of risk (low, medium, high risk industries). New studies, based on managerial interviews and further data analysis, will contribute to augment this envisaged trend for literature and managerial practice.

Conclusions

Three major topics are overlapping in this paper – the economic recession’s effects on Romanian economy, the entrepreneurship realities in the EU and Romania, and change management contributions to improve both of the above. Synthetizing few of the correlations between the three: economic environment determines entrepreneurship realities and highlights the need for a structured approach to change; entrepreneurship is considered a booster for the economic growth, but has been profoundly affected by the economic recession; change management represents an important asset to organization, especially during the economic crisis and recession, helping it to proactively relate to its turbulent environment.

Since 2008, when the economic recession started, European SMEs have been confronted with lower productivity and growth rate, lower capacity of innovation, difficulty in accessing credits and markets, difficulty in transferring business, punitive sanctions in case of failure and burdensome administrative procedures. During the 2008-2013 period, the Romanian economy experienced a profound structural change, while also facing a significant population decline. The recovery process has already begun – GDP started to increase in 2010, inflation rate decreased in 2013 by 1.6% and some of the most affected industries by the crisis are recovering, reaching a low or medium economic risk. In spite of that, the number of active enterprises has been continually decreasing, while most insolvencies cases (90%) have been of small enterprises.

Our set of analyses showed that small enterprises having turnover between 100 – 500 k euros need the most to be efficient in change management, in the economic recession context, because of high business risk. By estimating risk coefficients for 35 Romanian industries, it was possible to identify Romanian economic sectors that are highly challenged by the crisis (Tourism & Restaurant, Industrial Equipment, Electrical & Electronic Equipment and Constructions) and the ones that are in recovering process with a medium risk coefficient (Real estate, Beverage industry, Glass & Ceramics, Media & Advertisement, Sanitation, Metals, Retail and Food industry). These last industries also need a special focus on change management.

Change management implementation bears numerous benefits, for all organizations, regardless of their size, lifecycle or industry, but small enterprises’ peculiarities, especially when affected by recession, entail an even higher need for change management capabilities. This is because the effects of the environment dynamism and complexity seem to be even stronger in smaller organizations, while entrepreneurs do not have access to extensive information sources as managers of larger companies or multinationals.

Considering that the only constant in an entrepreneur’s life is change, from start-up level until a large company, and that while executives see change as an opportunity, employees see it as disruptive, intrusive and likely to involve loss, it is obviously necessary to manage changes in a structured and efficient manner. This might be the only difference between success and failure or insolvency.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

1. Abraham, C.L., Rempel, E.L., Rogers, C. (2006) ‘Complex economic dynamics: Chaotic saddle, crisis and intermittency’. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 29(5), 1194-1218.

Publisher – Google Scholar

2. Acemoglu, D. and Robinson, J. A. (2015) ‘The Rise and Decline of General Laws of Capitalism’. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(1), 3-28.

3. Anderson, D. and Anderson Ackerman, L. (2001) ‘Beyond Change Management: Advanced Strategies for today’s transformational leaders’, Jossey-Bass / Pfeiffer, San Francisco.

4. AnticrisisManager (2015) ‘Change Management needs for Romanian organizations’ – Unpublished Report.

5. Bayon, M. C. Vaillant, Y., Lafuente, E. (2015) ‘Antecedents of perceived entrepreneurial ability in Catalonia: the individual and entrepreneurial context’[Online]. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 5:3. [Retrieved July 29, 2015], http://link.springer.com/article/10.1186%2Fs40497-015-0020-0

Publisher – Google Scholar

6. Busenitz, L. and Barney, J. (1997) ‘Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making’. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 9-30.

Google Scholar

7. Churchill, N.C. and Lewis, V.L. (1983) ‘The Five Stages of Small Business Growth’. Harvard Business Review, 61(3), 30-50.

8. Covin, J. G. and Slevin, D. P. (1991) ‘A Conceptual Model of Entrepreneurship as Firm Behavior’. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 16 (1), 7-25.

Google Scholar

9. Edinburg Group (2013) ‘Growing the global economy through SME’s’. [Online] [Retrieved August 8, 2015], http://www.edinburgh-group.org/media/2776/edinburgh_group_research_-_growing_the_global_economy_through_smes.pdf

10. European Commission (2008) ’Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Commitee and the Commitee of the Regions. “Think Small First”. A “Small Business Act” for Europe’, [Online], [Retrieved July 23, 2015] http://eurex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2008:0394:FIN:EN:PDF

11. European Commission (2010). ‘Europe 2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth’,[Online], [Retrieved July 23, 2015], http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:2020:FIN:EN:PDF

12. European Commission (2012) ‘Flash Eurobarometer 354. Entrepreneurship in the EU and beyond’, [Online], [Retrieved July 23, 2015], http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_354_en.pdf

13. European Commission (2013) ‘Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan. Reiguiting the entrepreneurial spirit in Europe’, [Online], [Retrieved July 23, 2015], http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2012:0795:FIN:EN:PDF

14. European Commission (2014) ‘A partial and fragile recovery. Annual Report on European SMEs 2013/2014’, [Online], [Retrieved August 8, 2015], from http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sme/facts-figures-analysis/performance-review/files/supporting-documents/2014/

annual-report-smes-2014_en.pdf

15. Gilpin, R. (2000) ‘The Challenge of Global Capitalinsm: The World Economy in the 21st Century’. Princeton University Press.

Google Scholar

16. Fischer, J. (2006) ‘Navigating the Growth Curve’. Growth Curve Press

17. Gibcus, P.,Vermeulen, P. A. M., de Jong, J. P. J. (2009) ‘Strategic decision-making in small firms: A taxonomy of small business owners’. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 7(1), 74-91.

18. Nagy, A., Dezsi-Benyovszki, A., Gyorfi, L.Z., Pete, S., Szabo, T.P. (2013) ’Entrepreneurship in Romania. Country Report’, [Online], Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, [Retrieved August 2, 2015], http://www.gemconsortium.org/country-profile/103

Publisher – Googlescholar

19. Hambrick, D. C. and Crozier, L. M. (1985) ’Stumblers and Stars in the Management of Rapid Growth’. Journal of Business Venturing, 1, 31-45.

20. Keller, S. and Aiken, C. (April, 2009). ‘The inconvenient truth about change management’, [Online], McKinsey Quarterly, [Retrieved July 23, 2015], http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/organization/the_irrational_side_of_change_management

Google Scholar

21. Kotter, J. (1995) ‘Leading Change: Why transformation efforts fail’, Harvard Business Review, 73(2), 59 – 67.

Google Scholar

22. McGrath, R., MacMillan, I., Scheineberg, S. (1992) ‘Elitists, riks-takers, and rugged individualists? An exploratory analysis of cultural differences between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs’. Journal of Business Venturing, 7, 115-135.

Google Scholar

23. Nolan, R. L. (1979) ‘Managing the crisis in data processing’. Harvard Business Review, 57(1), 115-126.

24. Parida, V., Westerberg, M., Frishammar, J. (2012)’Inbound Open Innovation Activities in High‐Tech SMEs: The Impact on Innovation Performance’. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(2), 283–309.

Publisher – Google Scholar

25. Piketty,Th. (2014) ‘Capital in the Twenty-First Century’. Harvard University Press

Publisher – Google Scholar

26. Plante, L. (2012) ‘A guide for entrepreneurs who lead and manage change’, Technology Innovation Management Review, 27-31.

27. Project Management Institute (2013) ‘Managing Change in Organizations: A Practice Guide’. [Online], [Retrieved August 2, 2015], http://www.pmi.org/~/media/Files/Home/ManagingChangeInOrganizations_A_Practice_Guide.ashx

28. Project Management Institute (2014) ‘PMI’s Pulse of the Profession In-Depth Report: Enabling Organizational Change Through Strategic Initiatives’. [Online], [Retrieved August 2, 2015], http://www.pmi.org/~/media/PDF/Publications/Enabling-Change-Through-Strategic-Initiatives.ashx

29. Prosci (2014) ‘Best Practices in Change Management’ [Online], [Retrieved August 4, 2015], http://offers.prosci.com/research/Prosci-2014-Best-Practices-Executive-Overview.pdf

30. Prosci (2013), ‘Best Practices in Change Management’. Unpublished Report.

31. Rahman, H. and Ramos, I. (2010) ‘Open Innovation in SMEs: From closed boundaries to networked paradigm’. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 7, 471–487.

Google Scholar

32. Romanian National Statistic Institute (2014), ‘Romanian small and medium-sized enterprises’ evolution: 2010-2013’, [Online], [Retrieved August 8, 2015], http://www.insse.ro/cms/files/publicatii/pliante%20statistice/IMM_01_2014.pdf

33. Schneider, F. and Kirchgässner, G. (2009) ‘Financial and World Economic Crisis: What Did Economists Contribute?’, Public Choice, Vol. 140, No. ¾, 319-327.

Publisher – Google Scholar

34. Taher, N. A. B., Krotov, V., Silva, L. (2015) ‘A framework for leading change in the UAE public sector’. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 23(3), 348–363.

35. Uzunidis, D., Boutillier, S., Laperche, B. (2014) ‘The entrepreneur’s ‘resource potential’ and the organic square of entrepreneurship: definition and application to the French case’, [Online], Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 3:1, [Retrieved July 29, 2015], http://www.innovation-entrepreneurship.com/content/pdf/2192-5372-3-1.pdf

Publisher – Google Scholar

36. Van de Vrande, V., De Jong, J.P., Vanhaverbeke, W., De Rochemont, M. (2009) ‘Open innovation in SMEs: Trends, motives and management challenges’. Technovation, 29(6), 423–437.

Publisher – Google Scholar