Introduction

The study of managers aroused and still arouses the interest of researchers and organizations. In management, career is particularly widely discussed through the analysis of the manager’s population. Indeed, companies are concerned about manager career progress to attract, motivate and retain a quality workforce (Sturge et al., 2002). With the evolution of economic and organizational contexts, the concept of career has evolved. Paradigms have emerged and highlighted the changing behavior, attitudes and strategies of individuals to their careers. Managers have a greater role in managing their careers and the protean career highlights the proactive aspect of individuals in their careers. Also, it is interesting to analyze their perception on factors that could influence their career advancement or promotion because this will allow better understanding and management of this qualified personnel. Studies on promotions or hierarchical advancement have attracted a significant number of works in the management literature, and with the democratization of education and the massive entry of women in the labor market, there have been many studies on women’s careers.

Furthermore, the socialization in different environments (school, family, etc.) can notably influence the beliefs, values, personality traits, behaviors and trajectories of individuals. Thus, socialization can be characterized as “the process by which individuals acquire some of the values, attitudes, interests, skills and beliefs of the groups to which they belong to” (Safavian-Martinon, 1998, p.124). The education system would therefore provide skills and would also contribute to the construction of the professional identities of individuals.

In France, the “grandes écoles” graduates and the university graduates represent a population of managers with potential or with high potential. The objective of this work is to study the effect of the degree (“grandes écoles” degree and university degree), gender and age on the perceptions of individuals on work behaviors and characteristics that would influence the progress of career through comparisons of certain framework categories (man, woman, “grandes écoles” graduates, etc.). For example, Heisler and Gemmill (1978) identified the perceptions of students and managers on behavior allowing career advancements. In our research, particularly, we have shown that managerial characteristics are perceived generally as determining for the promotions. But women and university graduates attach more importance to technical skills than men and “grandes écoles” graduates. Whereas with age, individuals are more inclined to geographical mobility and risk taking and would give less importance to support needs in more advanced positions.

Theoretical framework

The perception of promotion procedures can have effects on attitudes, motivations and behaviors of individuals at work (Beehr and Taber, 1993). The expectancy theory or VIE model (valence, instrumentality, expectancy) developed by Vroom (1964) is one of the best known theories of behavioral research. Vroom (1964) was one of the first theorists to adopt a perception of motivation as an active process; its approach corresponds to a process theory (Plane, 2012). The VIE model allows highlighting the “behavioral strategy” of individuals who act to get a reward trough a rational choice (Safavian-Martinon, 1998), so it “aims to explain the choice of the individual at work according to their perceptions and efforts to contribute to the achievement of a task “(Plane, 2012, p.91). Promotion or career advancement is both a system of reward and a system of employee motivation. That’s why it is important to study what individuals perceive as important factors for promotion to better understand their choices and eventually to highlight the differences between the perception of employees and the organizational promotion system.

Therefore, several authors have studied the various factors and characteristics that can facilitate or, on the contrary, hinder career advancement. Thus, women and ethnic minority groups seem to face barriers in their ascent to higher positions (Daley, 1996). Some behaviors may also influence promotions. And the career advancement (or promotion) can be defined as a set of promotions and evolutions in the direction of the top of the hierarchy (Hall, 1976). For example, Heisler and Gemmill (1978) have identified the perceptions of students and managers on behavior allowing career advancements or hierarchical advances.

For students, the 3 most important factors are the task/communication effectiveness, managerial proficiency and organizational demeanor. For managers, the 3 most important factors are the managerial competences, organizational demeanor and superficial presentability. Thus, according to Heisler’s and Gemmill’s (1978) study, both groups would give more importance to factors linked to skills. Blevins et al. (1989) have also focused on the perceptions of promoting factors by comparing students in management and managers. Furthermore, Beehr and Taber (1993) worked on the perception of intra-organizational mobility and their model have demonstrated two channels:

– Performance-based channels : Performance-based channels include “exceptional performance” (such as having good ideas and initiative, coming up with lots of ideas, leadership ability, working long hours, etc.) and “reliable performance” (such as doing a good job, good attendance, experience and ability, etc.)

– Role-irrelevant channels : Role-irrelevant channels include “personal characteristics” (race, sex, educational level, personality and appearance) and “luck and favoritism” (such as getting the right breaks, having friends or relatives higher up, etc.)

Objective and Methodology

The objective of this work is to study the perceptions of managers on factors affecting promotions and to compare individuals according to the type of degree (a “grandes écoles” degree vs a university degree), age (three age groups: less than 35 years, 35-50 years, and over 50 years) and sex possibly to highlight differences. Our hypotheses are therefore as follows:

– The perception of the factors influencing promotions differs by degree of individuals

– The perception of the factors influencing promotions differs by age individuals

– The perception of the factors influencing promotions differs by gender

Using the factors of Beehr and Taber (1993) and Heisler and Gemmill (1978), which are questionnaires found in the literature, Savafian-Martinon (1998) conducted a selection of items that seemed most relevant to its population of “grandes écoles” graduates and university graduates and she completed the series with her qualitative study.

Our sample is similar to Safavian-Martinon (1998) and from various works, we have established a list of 25 items of beliefs about behaviors and characteristics that can influence career advancement or promotions. The intensity of the importance of each proposal or item was measured by a Likert scale with five answer choices: “not at all important”, “little important,” “moderately important”, “important” and “very important “.

We submitted our questionnaire to a population of “grandes écoles” graduates and university graduates who are currently employed. We have chosen to put it online for easy access and in order to reach a larger sample. We were able to get answers from 1370 individuals with 1023 “grandes écoles” graduates (engineering school or business school) and 347 university graduates (in science or management). With the concept of “perception of the factors influencing career advancement”, the objective is to generate a list of proposals for behavior or characteristic. We choose not to aggregate the characteristic into factor with a factor analysis in order to obtain a finer analysis of perceptions. Thus, any group of items taken independently will cover a maximum of perceptions of our population. Furthermore, our sample size allows us to keep each item individually. We tested the influence of the type of degree and sex on these perceptions by using variance analysis (ANOVA) which allows the study of the relationship between qualitative and quantitative variables and the influence of age using a regression that is used in the study of the relationship between two quantitative variables.

Results

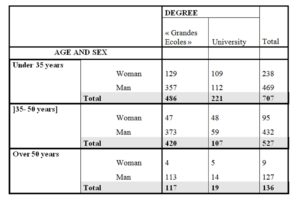

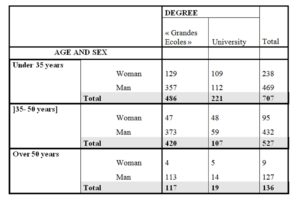

As detailed in Annex 1, our sample of 1370 persons contains 75% of “grandes écoles” graduates and 25% of university graduates, 75% of men and 25% women. When we look at the distribution by age, approximately 51.5% are under 35 years, 38.5% are between 35 and 50 years and 10% over 50 years.

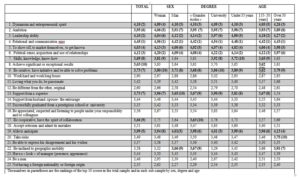

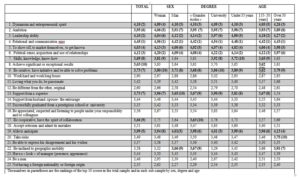

Annex 2 presents the average score for each proposal in the total sample and in groups by gender, type of degree and the age group. It appears that in all categories of managers, dynamism, ambition, leadership skills, relational and communication ease, ability to show themselves or to make themselves known, the political sense, creativity and to be able to anticipate (items 1-6, item 9 and item 19) are among the first 10 items with the highest scores. The support of a supervisor is also part of the 10 most important factors in all groups except for managers of “more than 50 years”. With categorization by sex, the item “skills, knowledge, know-how” appears in the top 10 factors scores in women and not in men, while the item “be inclined mobility geographic “appears in the top 10 scores of factors in men and not in women. With categorization by type of degree, among the 10 items with the highest scores, the item “skills, knowledge, know-how” appears in university graduates and not in “grandes écoles” graduates, while the items “inclined to a geographic mobility” and “being cooperative” are in the 10 best scores for “grandes écoles” graduates and not for university graduates. Finally, with the categorization by age, the age under 35 years and 35-50 years have the items “skills, knowledge, know-how “and” support a superior” among the 10 best scores in contrast to more 50 years. The individuals older than 50 years have the items “take risks” and “be inclined to a geographic mobility,” which do not appear in the top 10 score factors in individuals under 50 years. Furthermore, in individuals aged 35-50 years, the item “achieve good results even exceptional ones” constitutes one of the 10 most important factors for promotions while this is not the case for the other two groups, i.e. less 35 years and over 50 years. Annexes 3, 4 and 5 present the results of ANOVA and regression testing.

The following table summarizes all significant results:

Table 1: Significant Results of variance and regression tests

Discussion and conclusion

This work aimed to determine the perception of a certain category of managers (such as “grandes écoles” graduates and university graduates) about the factors or behaviors that could influence promotions. We have seen that whatever the manager category, the variables with the 10 best scores are more or less the same. This suggests that the managerial characteristics such as dynamism, ambition, leadership, communication ease and ability market themselves are perceived in general as determining promotions. To retain and motivate its managers and stay competitive in an increasingly aggressive market, companies must be able to generate formations or situations to develop these characteristics.

It is interesting to see in more detail the variables for which the differences or links are significant by sex, degree or age group. Thus, in our analysis by sex, we found that for all significant mean differences, women still have a higher average than men with the exception for the variable “be inclined to a geographical mobility ”. The average of this variable is not only higher in men but it is also part of their 10 best averages unlike women. Thus, men attach more importance to mobility than women. This result concurs with some studies which have shown that women are less willing to geographic mobility, especially international mobility. Some factors, such as age, sex, family situation and work experience internationally, have influences on the acceptance of an international assignment. Although, the influence of these factors on international mobility does not meet unanimity among researchers, we have noted some characteristics: the youth are more predisposed to mobility, women are more reluctant to accept mobility, the attitude of the spouse regarding mobility influences the decision of an international mobility (this would be more important for women than for men), having children (especially children under five years) and adolescents discourage international mobility, and finally, the highest paid managers would be more inclined to accept an international affection (their employment ensuring financial security) (Saba et Haines, 2002). But for international mobility, as recalled by Saba and Haines (2002), in the current context of globalization and international business development, mobility has become more important for executives. For the individual, the success of international mobility is seen as a career accelerator and success after the return is conceived by career progression with a promotion or increased responsibilities (Cerdin, 2004). According to Bournois (1991), the main reasons pushing executives to mobility in Europe would be “the hope of a future promotion or a better career development” (52%), “Personal and / or family experience in another culture” (21%), “the immediate promotion” (14%) and “compensation” (10%). This perception is more pronounced in men than in women and it could influence the differences in career success. In a context of international competition, companies should take into consideration that this mobility is less clear for women and should ensure better support to facilitate their mobility, positively influencing career success and also the satisfaction of these managers.

Moreover, in our analyses by age group, the item “be inclined to a geographical mobility” is significantly positively linked with age. Indeed, the average for this item is one of the 10 best averages in the people who are over 50 years unlike the under 35 and 35-50 years. Indeed, as stated by the survey of Saba and Haines (2002), older executives would more easily consider international mobility. This mobility is explained by the fact that they have less family responsibility and thus can find a way to escape from the career plateauing problems they often face. The other variable that marks the difference between the over 50 and under 50 years old is the item “take risks”. This item is part of the 10 best averages for the manager over 50 years in contrast to less than 50 years. Indeed, as in the case of international mobility, it seems that older managers can easily envision taking risks notably due to less family responsibility, a need to prove themselves to fight against to possible career plateauing and / or a risk of failure more easily surmountable financially with higher work experience. It is also interesting to note that for all variables significantly linked to age, this relationship is negative except for items “leadership ability”, “take risks” and “be inclined to a geographical mobility”. The perception of originality, support from a superior, spousal support, appreciation by colleagues or people under his responsibility and acceptance of criticism is higher among younger than among older managers. Indeed with age, individuals would give less importance to the judgments of others and need less support in more advanced positions. Companies can therefore be more attentive to these factors with younger managers to motivate and retain them.

Finally, in our analyses by type of degree, we note that for any significant mean differences, university graduates still have a higher average than “grandes écoles” graduates except for items “leadership ability” and “be inclined to a geographical mobility “. These two items are also among the 10 best averages of factors perceived as important for promotions in “grandes écoles” graduates unlike the university graduates. During their initial education, “grandes écoles” graduates have an obligation to stay abroad. Moreover, these institutions recruit the brightest students who have often privileged backgrounds and who are dedicated to the most prestigious and remunerative careers (Bouffartigue and Gadea, 2000). Therefore, this socialization may encourage “the acquisition of habitus or forms of know-who” (Bouffartigue and Gadea, 2000) in keeping with the belief of the importance of a leader’s profile for career development. Therefore, the perception of these variables as influencing the promotions seem more pronounced among “grandes écoles” graduates. Moreover, as with women compared to men, the item “skills, knowledge, know-how” has an average significantly higher among university graduates and one of the 10 best averages unlike “grandes écoles” graduates. So we can say that women and university graduates attach more importance to technical skills than their male counterparts and “grandes écoles” graduates.

Thus, in the light of these analyses, it is possible to better understand the perceptions of managers to understand the possible career differences, to act on their motivation, their involvement or their sense of recognition and allow their loyalty, which is one of the main issues of human resources and companies in a context of global competition

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Beehr, T. A and Taber, T. D (1993), « Perceived intra-organizational mobility: reliable versus exceptional performance as means to getting ahead », Journal of Organizational Behavior, vol.14, 579-594

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Blevins, D.E, Pressley, M.M. and Henthorne, T. L. (1989), « Perceptions of ethical and career advancement pratices: business executives vs. business students », American Business Review, 6-14

- Bouffartigue, P. and Gadea, C. (2000), Sociologie des cadres, La Découverte (ed), Paris

- Bournois, F. (1991), La gestion des cadres en Europe, Eyrolles (ed), Paris

- Daley, D. M (1996), « Paths of glory and the glass ceiling: differing patterns of career advancement among women and minority federal employees », Public Administration Quarterly, 143-162

- Dubar, C. (1991), La socialisation: construction des identités sociales et professionnelles, Armand Colin (ed), Paris.

- François-Philip Boisserolles De Saint Julien, D. (2005), Les survivants : vers une gestion différenciée des ressources humaines, l’Harmattan (ed), Paris

- Hall, D. T. (1976), Careers in organizations, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

- Heisler, W. J. and Gemmill, R. (1978), « Executive and MBA student views of corporate promotion practices : a structural comparison », The Academy of Management Journal, 21(4), 731-737

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Plane, J-M. (2012), Théorie et management des organisations, 3rd edition, Dunod, Paris

- Saba, T. and Haines, V. (2002), « Des cadres prêts à accepter une affectation internationale : une question de profil ou de pratiques incitatives? », Gestion, 2002/1, vol.27, 33-40.

- Safavian Martinon, M. (1998), « Le lien entre diplôme et la logique d’acteur relative à la carrière : une explication du rôle du diplôme dans la carrière des jeunes cadres issus des grandes écoles de gestion », Phd in Mangement, University Paris1-Panthéon-Sorbonne

- Sturges, J., Guest, D., Conway, N. and Mackenzie Davey, K. (2002), « A longitudinal study of the relationship between commitment among graduates in the first ten years at work », Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 731-7

14. Vroom, V.H. (1964), Work and motivation, Jossey-Bass

Annex 1: Descriptive statistics of our sample

Annex 2: Average score per item in the total sample and in the categories by sex,

degree and age

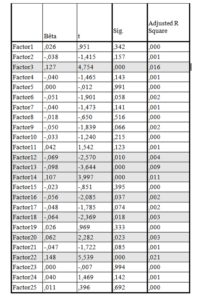

Annex 3: ANOVA results between sex and perception of the different variables that can influence promotions

Annex 4: ANOVA Results between type of degree and the perception of the different variables that can influence promotions

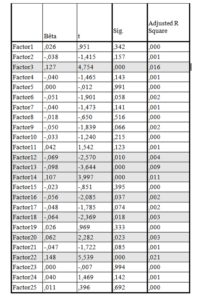

Annex 5: Regression results between the age group and the perception of the different variables that can influence promotions

Notes

HEC: Haute Etude Commercial

ENS: Ecole Normale Superieure

The VIE model: Considering behavior X (or an act, an effort level), a result Y (or performance) and Z reward (or consequence) according to this theory, the behavior X of an individual is due to three elements:

– The “Valence”, that is to say the value that the individual attributes to the likely consequences of his behavior namely Z reward;

– The “Instrumentality”: it is the probability perceived by the individual if they reach a certain performance level (Y result), they can get Z reward (Philip Francis Boisserolles Saint Julien, 2005). The instrumentality represents the concrete effects that the person hopes to achieve following on their efforts and performance (Plane, 2012);

– The “Expectation”: it is “waiting that an action is followed by a result called of first level (performance)” (Philip Francis Boisserolles Saint Julien, 2005, p.91), it corresponds to the expectation that the behavior X will lead to a result Y.

Communication effectiveness: Is able to argue logically; Is able to sell his ideas; Is willing to work more than 40 hours a week; etc.” (Heisler and Gemmil,1978)

Managerial Proficiency: Is willing to take suggestions from subordinates; Has the respect of subordinates; Is able to develop subordinates; etc.” (Heisler and Gemmill,1978)

Organizational Demeanor: Is willing to take suggestions from subordinates; Has the respect of subordinates; Is able to develop subordinates; etc.” (Heisler and Gemmill,1978)

Managerial Competences: Is willing to take suggestions from subordinates; Has the respect of subordinates; Is able to develop subordinates; etc” (Heisler and Gemmill,1978)

Organizational Demeanor: “Doesn’t complain about rules and procedure; Is an advocate of company policy” (Heisler and Gemmill,1978)

Presentability: “ Has a clean-cut appearance; Has a pleasant personality; look like a manager; etc.” (Heisler and Gemmill,1978)