Introduction

“The basic objective of corporate training as such is not, or should not be, only the development or changes in qualification, but primarily about achieving changes in the thinking, sentiment and engagement of employees” (Tureckiová, 2004, p. 92). Within this context, it is clear that corporate training involves the identification of training needs, planning and proposition of training activities, specification of the corporate training methods, and finally the evaluation of the training activities. None of these activities can be realised without guaranteeing there are adequate financial resources in place to do them. Corporate training is education arranged by companies in order to advance the professional development of their employees in a number of fields, and which usually corresponds to the business doings of the company (Průcha, 2003, p. 167).

Financial resources of corporate training in the Czech Republic

The financial resources used for the funding of corporate training can be divided into internal (i.e. own resources) and external (e.g. grants). The availability of financial resources for the funding of corporate training undoubtedly depends on company size and its business strategy. Small companies often do not have sufficient funds for the professional development of their staff. As a result, they search the labour market for employees who either do not require further training or who require only minimal training (e.g. legally required training). The costs for one day technical training or certification can be very high. Due to the legal obligations placed on Czech companies to spend funds on such activities, irrespective of company size, training in “soft skills” is often considered costly and ineffective.

The picture for larger companies is slightly different. With a larger budget at their disposal they have the room to decide what amount they are willing to expend on corporate training and on what fields the corporate training will focus. In comparison to small companies, these companies are more likely to organize training sessions in soft skills, in particular at the managerial level. Such training is not always considered essential for the given position. In some cases, the training is seen as one of an array of possible benefits for employees. At the same time, the companies themselves are well aware of the fact that such training deepens the professional qualifications of their staff and therefore improves their employees chances of being headhunted or employed by a competitor. In cases where training requirements are long-term and/or costly, a company (the employer) often requires the employee to sign a conditional contract. In other cases, a company may be willing to provide its financial support to education only if it does not lead to certification or a diploma. Unfortunately, these funds are also the first at risk if a company´s business activities slow, as was the case during the global economic crisis in 2009. Czech companies, whose success is largely tied to the economic fortunes of other European states, were also affected by the recession. As a result, funds intended for professional development were slashed. This has been reflected in the labour market in different ways. Since 1993, the number of employees has continually decreased, whilst the number of the self-employed has continued to grow. At the same time, there has been a permanent increase in the number of university-educated people i.e. those who are most interested in further education and who are either supported by their employers or are prepared to finance their education themselves or at least participate in the co-financing thereof (see Straková, et al., 2013). The situation is different in the case of people with only basic schooling. Kolomazník (2015) states that “An important factor for the participation of employees in the DV is the achieved level of education; in adulthood, employees with only basic schooling participate the least often in further education”. The last factor, but by no means the least important, is the migration of people towards towns where, especially in larger towns, people have higher salaries (and may be able to afford co-financing for their further education) and have a greater understanding of the importance of education as a pre-condition for social and working success (Donath-Burson-Marsteller, 2009). They are also better informed about the range of training and further education opportunities that are available.

Much detailed information on the situation in the Czech Republic is given in a report published in 2012 by the Czech Statistical Office (CSO) on the results of a survey conducted in 2011 into adult learning (the survey is conducted every five years and is compulsory for all EU states; the latest survey was conducted from 11 July, 2016 to 16 January, 2017). The report states that “The number of Czech companies which provide further professional training to their staff has been continuously growing. According to the latest survey conducted in 2010, about 72.2% of all Czech companies provided staff with professional training, whilst five years earlier this stood at 69.9%. Slightly more than half of employees´ working hours (51.6%) were spent undertaking compulsory training according to the legal standards valid in the Czech Republic, which includes occupational safety and health (OSH), fire prevention and protection, training for drivers, electricians, welders, etc. Over the range and types of courses available, significantly more men (64.4%) participated than women (35.6%). Five years after the 2005 survey, there has been a significant shift away from internal training courses to external ones (a shift of more than 20%). The proportion of expenditure on training in terms of overall costs decreased from 0.9% to 0.6% (CSO, 2011). The report also identifies three factors which constrained the provision of further education: a) the existing qualifications, skills and abilities correspond to the actual needs of companies; b) high training costs; and c) employees were not able to participate in courses due to work load and lack of free time. The latter issue is related to the accessibility of further education (the necessity to participate in training outside the usual workplace and/or outside the place of residence).

Proportion of Private and Public Funding For Corporate Training in the Czech Republic

According to the CSO (2011), in the Czech Republic, 68% of corporate training is supported through EU subsidies, and a further 23% through government grants (CVTS 4). The remaining 9% falls under other sources of funding.

The OECD (2016) monitors the proportion of overall private and public expenditure, at individual levels of formal education, on institutions of formal education. It states that in 2012, the proportion of private expenditure on primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education in the Czech Republic stood at 9%, which is comparable to the average values in other OECD countries (between 9 – 12%).

The results from these two reports show that there has been no significant change in the private funding of corporate training in recent years. It is interesting to note that, according to the CSO survey results (2011), after the economic crisis, companies radically abandoned external providers of training to concentrate on providing training for their staff from their own resources. The reason for this is the difference in costs, as well as the possible monitoring and control over the educational event and its quality. Kolomazník (2015) states that “Most employers (57%) provide in-house professional training to their staff. The services of external agencies are only used by 33% of employers.”

The CSO report (2016) notes that “with regards to changes over time, the international average of overall expenditure on primary to post-secondary non-tertiary educational institutions increased by about two thirds (OECD) or by half (EU21) between 2005 and 2012, whereas in the Czech Republic the expenditure in the same period remained flat.”

Corporate Training Support

In terms of corporate training, companies usually use internal financial resources. However, in some fields it is possible to access grants. This mostly concerns companies that provide educational services and which rely on “European” funds – Czech funds sent to Brussels, which are then “returned” to the Czech Republic. The Czech Republic is then expected to participate in the co-financing of corporate training (Mužík, 2012).

The programmes from which companies can obtain funds are published on the websites of the appropriate Czech institutions or on EU portals. The European portal for small companies regularly publishes a database of all operational programmes administered by the member states and financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) or by the Cohesion Fund. An example of this is the financial support for professional training programmes in the agriculture, forestry and food sectors within the framework of the Rural Development Programme 2014 – 2020. In addition, projects under the European Social Fund (ESF), which have existed for 60 years, endeavour to ensure that employees and jobseekers can utilize the opportunities for lifelong learning and therefore maintain their vocational skills and qualifications in accordance with the needs of industry and economic development. One of the EU programmes directly focused on education is called “Supporting the Training of Employees” (in Czech – Podpora odborného vzdělávání zaměstnanců II – POVEZ II), whereby the target groups are employers pursuant to § 7 of the Labour Code (a company or its branch established outside the City of Prague), their employees, or potential new employees.

Methodology

The aim of this paper is to determine the structure of financial resources for corporate training. The following hypothesis was set: “90% of all companies fund corporate training solely from their own resources.”. Empirical research was conducted in the form of a questionnaire survey. The survey was conducted in the second half of 2016. A sample set of companies was selected in cooperation with the Czech Statistical Office. The sample set included companies in all size categories, as defined below. The companies were selected in compliance with the EU nomenclature with regards to the basic spheres of the national economy and legal subjectivity. In total, the sample set consisted of 1,420 companies. The questionnaire survey was conducted by students and members of the academic staff of the Institute of Technology and Business in České Budějovice, as well as electronically. In total, 607 questionnaires were completed in this way. The structure of the research sample was as follows:

|

Micro-company (< 10 employees)

|

141

|

23.2%

|

|

Small company (10 – 49 employees)

|

179

|

29.5%

|

|

Medium-sized company (50 – 249 employees)

|

164

|

27.5%

|

|

Large company (≥ 250 employees)

|

123

|

20.3%

|

|

Total number of companies

|

607

|

100%

|

The questionnaires were processed and evaluated by means of mathematical-statistical methods. The sample set of 607 companies was divided into four groups according to their size: micro companies (< 10 employees), small companies (10 – 49 employees), medium-sized companies (50-249 employees) and large companies (> 250 employees). Tables were generated for each group according to the frequency of responses to the question relating to the financing (funding) of corporate training (see Table 1; 3 ; 5 ; 7). Those companies that did not include any forms of funding for corporate training were subsequently disqualified from further data processing. The focus with the remaining companies was on the frequency of the response “solely own financial resources” in comparison with the frequency of responses to other questions. The null hypothesis – 90% of all companies fund corporate training solely from their own resources – was statistically tested. To verify this, a one-sided one-sample test at a reliability level of 95% was conducted i.e. at a significance level of 0.05. In addition to a statistical test value and a p-value as the level of marginal significance within this statistical hypothesis test, an upper limit for the one-sided interval estimate was set for the proportion of companies that fund their corporate training solely from their own resources. If the calculated p-value was less than the significance level of 0.05, or if the upper limit of the interval estimate was less than 0.9, it would statistically indicate that the number of companies funding the training solely from their own resources is significantly less than 90%. The statistical tests were performed using R Statistical Software. The tables were generated using MS Excel (see Tables 2; 4; 6; 8).

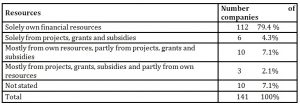

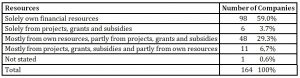

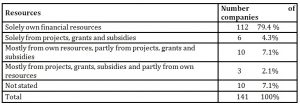

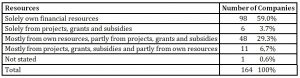

Table 1: Response rate – structure of financial resources – micro-companies

The sample set for this group of companies included 10 companies that did not state the forms of funding. These were not included in the statistical tests.

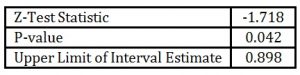

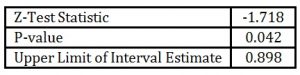

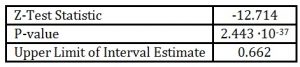

Table 2: Results of the statistical tests – micro companies

The statistical test results (see Table 2) show that the proportion of companies funding corporate training solely from their own resources is less than 90%. However, the results are close. The p-value is 0.042, which is very close to the significance level 0.05, and the upper limit of the interval estimate is almost equal to 0.9. The result is therefore borderline.

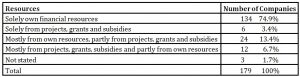

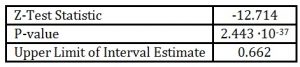

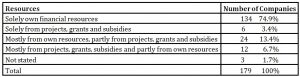

Table 3: Response rate – structure of financial resources – small companies

The sample set for small companies included three companies that did not state the forms of funding. These were not included in the statistical tests.

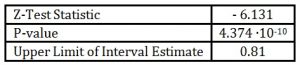

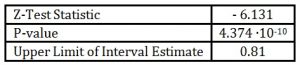

Table 4: Results of the statistical tests – small companies

The statistical tests quite clearly show that the proportion of companies funding corporate training solely from their own resources is significantly less than 90% (see Table 4). The p-value is much less than the significance level of 0.05 and the upper limit of the interval estimate is 0.81 (81%), 9% below the set limit.

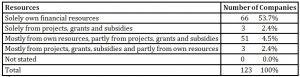

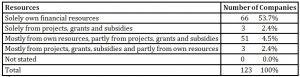

Table 5: Response rate – structure of financial resources – medium-sized companies

The sample set of 164 medium-sized companies included one that did not state the forms of funding. It was therefore excluded from the subsequent data processing.

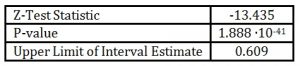

Table 6: Results of statistical tests – medium-sized companies

The statistical tests clearly (see Table 6) show that the proportion of companies funding corporate training solely from their own resources is significantly less than 90%. The p-value is negligibly small and the upper limit of the interval estimate is 66.2%. Taking into consideration that it is an upper estimate at the given confidence level, the real proportion may be even lower.

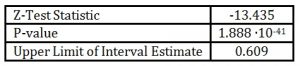

Table 7: Results of statistical tests – medium-sized companies

All the companies in the sample set for this group identified their resources for funding corporate training. The complete sample set was therefore used for the statistical tests.

Table 8: Results of the statistical tests – large companies

The situation within large companies is similar to that of medium-sized companies (see Table 8). The p-value is even smaller and may be considered to be almost zero. The upper limit of the interval estimate is even lower than the one observed for medium-sized companies i.e. less than 61%. Therefore, the real proportion of companies funding corporate training solely from their own resources may indeed be less than 60%.

Conclusion

Regardless of their size, the proportion of companies funding corporate training only and solely from their own resources is not 90% or more. Theoretically, small companies and micro-companies are close to the borderline, since the proportion is over 80%. In contrast, the proportion for medium-sized and large companies ranges from 50 to 65%. This implies that a relatively large number of medium-sized and large companies at least partially resort to external sources of funding. It can therefore be stated that the larger the company, the smaller the proportion that funds corporate training only and solely from their own resources. The 90% borderline would certainly be achieved if the proportion also included those companies that (partially) use external resources for this purpose. The proportion of companies that (almost) fully fund their corporate training needs through external resources is in fact 10% for micro-, small, and medium-sized companies, whilst it is under 10% for large companies.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- AMSP ČR. (2012), ‘Pravidla pro efektivní využití vzdělávací akce/aktivit,‘ [Online]. [Retrieved March 21, 2017]. Available: http://www.amsp.cz/7-pravidla-pro-efektivni-vyuziti-vzdelavaci-akce-aktivit.

- Armstrong, M. (2009), Armstrong’s handbook of human resource management practice, (11th ed.), Kogan Page, London .

- Bartlova, P. (2008), BADED – barriers in adult education: findings and strategies for overcoming those barriers: Ikaalinen – Prague – Vienna, National Training Fund, Praha.

- Bouckaert, J. and De Borger, B. (2012), ‘Price competition between subsidized organizations,‘ Journal of Economics, 109 (2), p. 117–145.

- ČSÚ. (2011), ‘AES Vzdělávání dospělých 2011.’ [Online]. [Retrieved March 21, 2017]. Available: https://www.czso.cz/csu/xu/aes-vzdelavani-dospelych-2011.

- ČSÚ. (2016), ‘Financování vzdělávání v České republice v mezinárodním srovnání.’ [Online]. [Retrieved March 21, 2017]. Available: https://www.czso.cz/documents/10180/46834153/23004816_1.pdf/93225018-a60e-4b5a-8621-d8840289157d?version=1.

- Donath-Burson-Marsteller. (2009), ‘Vzdělávání dospělých v ČR: Průzkum vnímání problematiky vzdělávání dospělých odbornou a laickou veřejností.‘ [Online]. [Retreived February 02, 2017]. Available: http://www.msmt.cz/uploads/Dalsi_vzdelavani/Zprava_z_pruzkumu_o_vzdelavani_dospelych.pdf.

- Heffernan, S. A., Fu, X. and Fu, X. M. (2013), ‘Financial innovation in the UK,’ Applied Economics, 45 (24), p. 3400-3411. doi:10.1080/00036846.2012.711942.

- Kolomazník, T. (2015), Zaměstnanci a další profesní vzdělávání: postoje, zkušenosti, bariéry. Fond dalšího vzdělávání. Výstupní analytická zpráva projektu KOOPERACE (Koordinace profesního vzdělávání jako nástroje služeb zaměstnanosti; reg. č. projektu: CZ.1.04/2.2.00/11.00017). [Online]. [Retrieved March 10, 2017]. Available: https://www.google.cz/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=89&ved=0ahUKEwi-v5LowN3SAhUDtxQKHfXWBe04UBAWCDswCA&url=https%3A%2F%2Fkoopolis.cz%2Ffile%2Fhome%2Fdownload%2F1049%3Fkey%3D1a5edcab4b&usg=AFQjCNFtsU6Pxjh45ACCI-yYllnUE493gA&sig2=F8MYRCGFpFQtBevUYWhRDA&bvm=bv.149760088,d.d24.

- MŠMT. (2015), ‘Podpora odborného vzdělávání zaměstnanců II (POVEZ II).’ [Online]. [Retrieved February 17, 2017]. Available: https://portal.mpsv.cz/upcr/esf/projekty_v_realizaci/celorep/povez-ii.

- Mužík, J. (2012), Profesní vzdělávání dospělých, Wolters Kluwer, Praha.

- Národní ústav pro vzdělávání. (2011–2017), ‘Vzdělávání v ČR.‘ [Online]. [Retrieved March 20, 2013]. Available: http://www.nuv.cz/vzdelavani-v-cr/.

- (2016). ‘Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators.’ [Online]. [Retrieved March 17, 2013]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2016-en.

- Průcha, J. (2003), Pedagogický slovník, Portál, Praha.

- Straková, J. et al. (2013), ‘Hlavní zjištění z mezinárodního výzkumu vědomostí a dovedností dospělých PIAAC.’ [Online]. [Retrieved March 28, 2013]. Available: http://www.piaac.cz/attach/vysledky/PIAAC_hlavni_zjisteni.pdf.

- Turecková, M. (2004). Řízení a rozvoj lidí ve firmách, Grada, Praha.

- S Vyhnálková, K. (2007), ‘Vzdělávání dospělých v České republice a Evropské unii,’ 1st ed. Praha: Univerzita Jana Amose Komenského.Euroskop. Vzdělávací programy EU. [Online]. [Retrieved February 06, 2017]. Available: https://www.euroskop.cz/612/sekce/vzdelavaci-programy-eu/.