Introduction

Internet technologies offered new opportunities to businesses and created a way for new online business models (Hsu et al., 2014). Group buying is another form of e-commerce and relatively new business model. It has created new prospects for businesses to sell different products and services in the form of deals on their websites. Group buying or demand aggregators cluster disparate bargain hunters into one while offering lowest price. It works on the principle that “prices on multiple units fall as the number of buyers increase” (Yuan and Lin, 2004).

As there are several benefits with e-commerce web sites such as ability to promote products globally with significant cost savings, many businesses have opened their store fronts online (D&B, 2013). However, fierce competition among these on-line businesses has flagged the way for new business models such as “Group buying” or “Collective buying” (Zhang et al., 2012). This model resembles “Revenue sharing” model, as group buying sites sell the negotiated deals, but neither of them manufacture goods nor deliver services themselves. This revenue sharing model allows group buying sites to gain percentage of share in profit for each sale they make through their websites.

Group buying sites negotiate price and their share with the products and services’ suppliers prior to offering it as a deal, and then promote that deal on their website (Yuan and Lin, 2004). For this deal to come into effect, this offer needs to be purchased by the minimum number of customers. This number is mutually agreed and set upon through the negotiation process with the supplier. If the deal is not purchased by the required number of customers, then the deal will be not be made available to already purchased customers and the money that has been paid will be refunded (Coulter and Roggeveen, 2012). Although refunding money would not cause any financial losses to the group buying site, customers may perceive it as a “bad buying experience” (Dulleck, 2011), as they have already paid for the deal and expects stability from the group buying site. This can sometimes lead to negative reputation of the group buying site and may alter customers’ intention to return to that particular group buying site (Hsu et al., 2014).

Although Group buying sites have similarities with e-commerce business models, they do differ from regular e-commerce websites, but there is a significant similarity with daily deals websites in terms of the deals offered. In the case of daily deals web sites or “Demand Aggregators”, deal would be offered for a day or 24 hours at a discounted price whereas, group buying sites will have a fixed amount of time that can range from few hours to several days to allow its customers to purchase that deal from their website and to achieve minimum sale target. Usually, these timelines may change from one site to another site ranging from anywhere between 24 hours to several weeks.

Undoubtedly, group buying sites are gaining attention for their unique business models and their potential to promote and sell products and services online. However, it is important for group buying sites to act quickly to respond to customers’ needs and promote new products and services for increasing their sales. Therefore, we trust that a clear understanding of the influencing factors mentioned in this paper can help managers to divert their attention and resources to specific sections that are proven to be contributing to overall sales.

This paper is organized as follows. Literature review is presented to shed light on Group buying models and relevant research in this area. It lays the foundation for the hypotheses presented in this paper. The research setting and methodology in the following section explains the approaches adopted in this paper to understand relationships between different factors. Results are presented in the following section along with analysis. Based on the findings, discussion is made to elaborate the implications of this research.

Literature Review

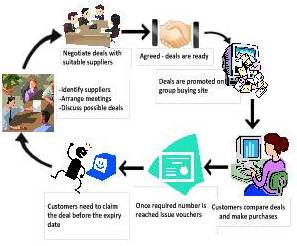

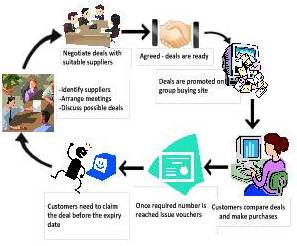

With the entry of new group buying sites, competition among businesses got intense. As a result, some group buying companies have exited the market or changed their business model to become “Deal aggregators”. Fig. 1 shows the online group buying model. For example, Australian group buying market has breached $500 million mark in 2012 and this trend is expected to continue as some of these top group buying sites in Australia have recorded more than 40% growth in their business (Stafford¸ 2012).

In the recent years, group buying model has been adopted by a record number of businesses around the world. Research has shown that more than 1548 group-buying websites have been launched in 2013 alone in China (Hsu et al., 2014). According to Statista (2014), group buying market in China reached US$5.5 billion in 2012. Groupon in USA has grown from 400 customers to 4 million customers in their early years. In fact, this Chicago based company has about 35 million subscribers in more than 300 cities worldwide (Statista, 2014).

Fig. 1: Online Group Buying Model

Although, there are more than 250 group buying sites operating in Australia, Living Social, Scoopon, Spreets (currently operating as a Deal Aggregator), Cudo, Groupon and Our Deal have gained 25%, 17%, 14%, 13%, 10% and 7% market share in Australia respectively in 2011 (Chang and Chou, 2014). Most of these online sites maintain their competitive advantages by offering range of products and services as low cost deals. As cost is one of the deciding factors for customers, ensuring the low cost for the deals offered online and maintaining these deals regularly is a key challenge for group buying sites to maintain competitive advantage. On an average, acquiring a new customer may cost the business in between $5-15 per customer (Johnson et al., 2013). In fact, the cost of acquiring new customers would be 5 times more than retaining the existing customers (Chang and Chou, 2014). Therefore, it is important for these sites to minimize churn rates.

Theoretical Background

Consumer behavior model proposed by Kotler et al., (2013) suggests that marketing, economic technological, political and cultural stimuli consists of the marketing mix including products and services, price, timing of sale and conditions on purchases such as purchase limits can influence consumer psychology. Consumer decision model developed by Blackwell et al., (2001) further explains that individual’s motivation to purchase a product or service and their perception of value for their purchases are the result of behavioral modification occurred through the stimuli. Research by Johnson et al., (2013) also suggests consumer behavior is clearly influenced by different stimuli that can lead to purchase decisions. Therefore, product or service marketability online, cost, discounts, timing and restrictions such as purchase limits are considered for research.

Research Background and Hypotheses

Undoubtedly, group buying sites are gaining popularity for the deals they offer on their websites. However, there is a vacuum in terms of identifying what prompts customers to revisit these sites to buy deals. In order to understand the influencing factors, this research studies several factors including Discount rate, Deal price, Deal categories and Time frame to utilize the deal. This study closely examines the impact of these factors on the overall sales. These results are expected to support group buying sites to further improve ways to promote deals on their website and boost their overall revenues.

Online Discounts

Discounting can be viewed as a strategy of reducing the actual price of a product or service to promote sales. Discounts are generally offered in the form of introductory offers, buy-ahead offers, seasonal offers and so on. Online or virtual store fronts gained reputation for offering huge discounts. These stores typically follow “pure clicks” or “clicks and bricks” strategy with minimum or no physical stores. As these sites operate with minimum staff and tight budgets, it is possible for them to achieve significant cost savings, which can then be offered as discounts to customers (Yuan and Lin, 2004).

Dulleck (2011) suggests that the demand for any product or service can be significantly increased by offering discounts. Discounts in general improve sales, particularly short term discounts gain customers’ attention quickly as customers may feel that these prices would not last long (Gabler and Reynolds, 2013). Discounts for a prolonged period of time may lead to postponement of purchases (Coulter and Roggeveen, 2012). Group buying sites use the idea of “buy-ahead discounts” to generate advance income. In practise, further discounts on additional purchases can encourage customers to buy more. As group buying sites offer huge discounts to attract customers, we formed an opinion that customers would pay attention to the discounts offered on group buying sites prior to deciding on purchases. Therefore, we hypothesize the impact of discount rate on overall sales for that particular deal.

Hypothesis 1: The Discount Rate Offered on the Deal Has Improved Sales for that Deal

Actual Cost of Deal

Price can be defined as the amount that a customer is willing to pay for a product or service. It is the key element in marketing mix and plays a vital role in convincing customers to buy a product or service (Coulter and Roggeveen, 2012). Several businesses including Amazon and Dell came up with low-cost business models to sell their products online at a lower cost. Other companies have come up with innovative ideas such as “Name your own price”, where customers will be able to quote the price they are willing to pay for a specific product (Dulleck, 2011).

Online business models can achieve significant cost savings by eliminating expensive retail space. As online retailing model allows cost savings, customers expect these savings to be passed on to them. As a result, they choose to buy online instead of visiting traditional stores. Online shoppers can also compare prices and the reliability of these retailers through customer reviews and relevant online forums. Research conducted by Dulleck (2011) indicates that a product’s price influences customer buying behavior. It is found that customers may use price as an indicator of quality. Although, customer makes a decision on whether to buy a product or service, price of the deal can play a vital role in the decision making process. Books, consumer electronics, athletic apparel, sporting goods, shoes and pet supplies are among the most commonly purchased items online (Dulleck, 2011). As the prices of these items are significantly less compared to luxury items, we assumed that online shoppers look for discounts and tend to buy low cost items online. Therefore, we hypothesize that low priced deals would be sold more compared to expensive items.

Hypothesis 2: Low Priced Deals are Sold More Compared to Expensive Items

Marketable Products and Services Online

Online retailing in Australia has seen a study growth in the past few years. Australian online shopping expenditure is expected to reach $26.9 billion by 2016 (PwC, 2014). In fact, 34,000 Australian businesses are already using PayPal for financial transactions, which indicate their awareness on the growth of online retailing in Australia (PwC, 2014). While these figures are encouraging, there is a limit to what products can be sold online. Demangeot and Broderick (2010) provide a list of goods that can be marketed online. This list includes cosmetics and beauty products, liquor, books and media, electrical items, sporting and outdoor equipment. Surprisingly, food and alcohol is nowhere to be seen on online shoppers’ list. Research done in 2013 found that customers prefer to try those products at a physical store prior to making purchases (PwC, 2014).

Coutler and Roggeveen (2012) also indicate that food and beverages are the least purchased items online. Group buying sites use Internet as a medium to sell products and services which will be delivered by a third party (Wibowo and Grandhi, 2014). However, it has similarities to e-retailers in terms of advertising and promoting products and services. It can be presumed that group buying concept depicts online retailing. Therefore, deals relating to food and alcohol are expected to be sold less compared to other items.

Hypothesis 3: Food and Alcohol Vouchers are the Least Purchased Items from Group Buying Sites

Time Frames to Utilize the Deal

In the case of traditional purchases, customers are able to receive goods or services at the same time or at a mutually agreed times. As for group buying sites, purchased deal would not be made available until required numbers of deals are sold (Demangeot and Broderick, 2010). Group buying sites indicate approximate time to deliver physical goods, and then vouchers are issued with specific expiry dates to redeem deals that involve activities.

Coutler and Roggeveen (2012) state that short term promotions help to accelerate sales. Displaying time left to purchase can also improve sales as customers may have fear of losing out. While this approach improves sales, it can also play a significant role on post purchase events because of the time limits to redeem and consume the deal purchased. Sometimes, customers may perceive this as a possible financial risk, as they may fear of missing deadlines (Wibowo and Grandhi, 2014).

PwC (2014) highlights that group buying customers are concerned about the expiry date of deals purchased. As group buying sites work on the basis of limited-time deals, it may trigger impulsive buying behavior. It is also revealed that time limits to redeem the voucher, and terms and conditions are one of the major reasons for user dissatisfaction on group buying sites. In order to deal with the increasing number of complaints, code of conduct for Australian Group buying websites has been developed (ADMA Australia, 2014). We hypothesize that allowing longer time to redeem the voucher can significantly improve sales for that particular deal.

Hypothesis 4: Lesser Time to Redeem the Voucher Can Negatively Impact Sales for that Deal.

Research Setting and Methodology

Although there are more than 250 group buying sites registered and operating in Australia, Canstar Blue’s survey done in 2013 indicates that Cudo, Groupon, Ourdeal, Living Social and Scoopon performed well in several aspects and achieved better rating for overall satisfaction, value for money, quality, ability to use coupons, relevance, site navigation and customer service (Canstar Blue, 2013). Therefore, these top 5 group buying sites are chosen for data collection and analysis.

One of the largest home-grown e-commerce businesses, Cudo, joined Australian commerce in 2013. It employs over 150 staff and sells more than 100,000 deals monthly (Cudo, 2014). Ourdeal site was launched in 2010 with the expectation to provide $5 million savings to its customers. It is currently offering deals to customers in 17 different cities and neighboring suburbs in Australia (Ourdeal, 2014). Living Social is a global company which maintains its presence in 16 countries outside the United States. It offers deals to 33 cities and surrounding suburbs in Oceania, 54 cities in Europe, 311 cities in North America, 8 cities in Asia and 2 cities in South America. It has more than 600 million subscribers worldwide and sold more than 205 million vouchers by the end of 2013 (LivingSocial, 2014). In Australia, it sells deals to 13 cities and surrounding suburbs regularly. Living Social was ranked number one in 2011 with a market share of 29% (Chang and Chou, 2014).

Started in 2001, Groupon Australia is one of the fastest group buying companies in Australia. It maintains its presence in 48 countries around the world. At the moment, Groupon Australia sells online deals to customers in 9 Australian cities and surrounding suburbs (Groupon, 2012). Home grown site Scoopon started in 2010 from a garage. Within 3 years of its launch, it has become one of the leading daily deals company and integral part of Australia’s number 1 online shopping group (Scoopon, 2014).

The Sample

When the population is large, systematic sampling is beneficial as it can produce similar results to random sampling (Taylor, 2007). There are more than 250 group buying websites operating in Australia with each offering several deals (AlltheDeals, 2013). As sample size is bigger, we have used systematic sampling approach to collect data from the top 5 Australian group buying sites namely: Cudo, Ourdeal, Groupon, LivingSocial and Scoopon (Canstar Blue, 2013) during festive season as customers’ participation rate would be high at this time. Although some of these groups buying sites maintained their presence in other countries, data is collected only from their Australian websites for consistency. All 5 group buying sites offered specific deals for customers in different cities in Australia. As Sydney is the major city in Australia in terms of population and size, it is assumed that these group buying sites would offer a range of products and services to Sydney based customers. This will have an impact on participation rates and overall sales. Sample size will have an impact on accuracy of a confidence interval. Larger population size can increase the accuracy of results (Liu et al., 2014). Therefore, Sydney’s web page dedicated for local customer was chosen for data collection.

All 5 chosen group buying sites have categorized deals for easier navigation and offered several deals each day with varying deal ending date and time. However, except Cudo, all other sites have offered different featured deal each day on entry page, whereas Cudo chose to promote travel deals on the entry page. As there are several deals offered by each of these sites with different start and end times, it would be impractical to collect data for all the deals offered. Therefore, for each featured deal, we have collected (i) Discount rate, (ii) Deal price, (iii) Product category and (iv) Time to utilize the deal. In case of Cudo, the first deal offered on its entry page is selected as a featured deal. This data was collected from all 5 group buying websites on every evening continuously for four weeks during Christmas season in 2013.

Results and Analysis

Descriptive Statistics

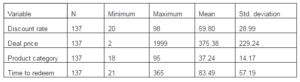

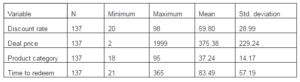

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of the collected data. While the average discount offered was about 60%, the minimum and maximum discounts offered by the group buying sites were 20% and 98% respectively. The Deal price indicate that the average price that customers spend on group buying websites is around $375.38. The Time allocated by the group buying website to redeem a particular product is 83.49 days. A total of 57,888 vouchers were purchased collectively from the chosen group buying sites in 4 weeks, suggesting the popularity of group buying sites in Australia. All these results indicate that online group buying websites, if adopted appropriately, can have a positive impact on the companies’ revenue.

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics

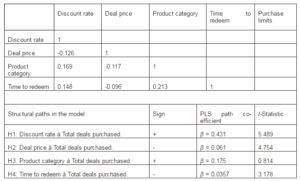

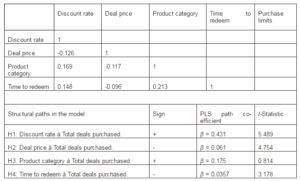

We adopted Pearson’s bivariate correlation analysis to evaluate a possible correlation between the studied variables. Pearson’s bivariate correlation analysis is considered relatively less sensitive to violation of assumptions of normality, and can estimate complex models with a relatively small sample size (Gefen et al., 2000).

Based on the analysis of the measurement model, we found that (i) Discount rate is positively correlated with Total deals purchased, and (ii) all study variables except Deal price are significantly correlated with Total deals purchased. However, the direction of some coefficients’ signs is opposite to the expectation, and it is necessary to further examine the structural model.

To test the research hypotheses, structural equation modeling was performed using AMOS software. Unbiased and maximum likelihood estimation covariance analysis properties were selected using AMOS.

Table 2: Correlations

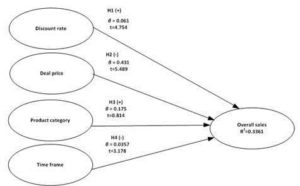

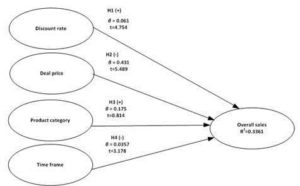

Overall, the model’s fit was acceptable. The observed chi-square χ2/df = 6.1 and the RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) = 0.068. A general rule of thumb is that a RMSEA ≤ 0.05 indicates a close approximate fit, and values between 0.05 and 0.08 suggest a reasonable error of approximation (Browne and Cudeck, 1992). Other additional goodness-of-fit indices are the NFI (normed fit index) = 0.973, the NNFI (non-normed fit index) = 0.928, the GFI (goodness-of-fit index) = 0.971, the AGFI (adjusted goodness-of-fit index) = 0.953, and the CFI (comparative fit index) = 0.979. While the overall model tests support the proposed conceptualization with the sample, the hypotheses refer to the significance tests of the specified paths. Fig. 2 shows the hypothesized path diagram with standardized path coefficients and squared multiple correlations.

We used three criteria to examine the validity of the structural model including the R2 values of dependent constructs, the path coefficient values, and the goodness-of-fit (GoF) value for the model (Henseler et al., 2009). The R2 value for the model shows that the Discount rate, Deal price, Product category and Time to redeem collectively accounted for 33.61% of the variance in Total deals purchased. The result is adequate according to the recommendations (0.67 = substantial, 0.33 = moderate, 0.19 = weak) for dependent variables by Chin (1998). The results are shown in Table 2.

It can be seen from Table 2 that Discount rate has a significant positive influence on the Total deals purchased (β = 0.330, p 0.05). This indicates that the low priced deals do not necessary be sold more compared to expensive items. Thus, H2 is not supported. The results also show that Product category has a positive impact on the Total deals purchased (β = 0.175, p < 0.001), which supports H3. Time to redeem has a negative influence on the overall sales (β = -0.0357, p < 0.001) which does not support H4.

Fig. 2: The Hypothesized Path Diagram with Standardized Path Coefficients

Discussion

This section presents a summary of the main findings with details. Overall, most of the empirical results confirmed the established hypotheses, but some were also unexpected. As expected, generous discounts generate more sales from group buying customers. This result is consistent with the findings of previous studies that group buying websites which offer large discounts can generate more customer traffic and higher sales (Wibowo and Grandhi, 2014). However, it is also observed that offering a very large discount may have negative effects on the customers’ perception of quality (Statista, 2014). When a price discount is too large, customers may be suspicious of the sale prices, in such a way that they may view the lower selling prices, rather than the higher initial price, as the true value of the item. Thus, group buying websites have to be very careful on deciding the price discount rate to be offered to the customers.

It is perceived that low priced deals would be sold more compared to expensive items. The results show that this is not generally true. Customers tend to purchase products that meet their requirements and specifications even though the price of that particular product tends to be high. It is observed that customers are brand conscious and are very careful about the quality of products offered on the group buying website.

It is believed that food and alcohol are expected to be sold less compared to other items on the group buying website. The results reveal that around 30% of the products sold on the group buying websites are based on food and alcoholic products. The results indicate that customers usually conduct a well-thorough research on the food products that they are interested to buy and then purchase their products through the group buying websites. Therefore, selling food and alcoholic products of the group buying website is a good way for increasing the company’s sales.

It is perceived that allowing longer time to redeem the voucher can significantly improve sales for that deal. Customers tend to conduct more research on the product before making the final decision. They prefer to wait until the last minute before purchasing a specific product on the group buying website. They tend to conduct more research on the product before making the final decision. The time limit to redeem the voucher does not influence the purchase outcome of a product.

Research Implications and Conclusions

Based on our results, we are able to offer some specific meaningful conclusions for group buying websites to improve their overall sales. Firstly, the discount rate plays a significant role in the number of products sold on the group buying website. Therefore, launching deep discounts may be a good way for new or struggling ones, to solicit business and advertise their brands. Secondly, group buying websites may need to consider promoting expensive items online. This is because customers are confident of what they would like to purchase online and they believe that they are able to obtain a higher discount rate as compared to physical stores.

Thirdly, we found that group buying websites can achieve greater group buying effectiveness and increase their market share by promoting food and alcoholic products online. There is a very high demand for these products and the group buying websites can potentially attract new customers to purchase food and alcoholic products by designing appealing features and setting good discounts.

Lastly, even though group buying websites work on the basis of limited-time deals, it is found that time limits to redeem the voucher do not significantly improve sales for that particular deal. Thus, it is critical for group buying websites to explore other alternatives for attracting customers to purchase a particular deal by including more discount or additional accessory products.

References

1.AlltheDeals. (2013). [Online], [Retrieved August 20, 2014], http://www.allthedeals.com.au/deal-sites.

Publisher

2.ADMA Australia. (2014). “Group Buying Code,” [Online], [Retrieved July 15, 2014],http://www.adma.com.au/comply/group-buying-code

Publisher

3.Blackwell, R. D., Paul, W. M. & Engel, J. (2001). ‘Consumer Behaviour,’ 9th edn, Harcourt, Orlando.

4.Browne, M. W. & Cudeck, R. (1992). “Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit,” Sociological Methods Research, 21 (2), 230-258.

Publisher – Google Scholar

5.Canstar Blue. (2013). “Group Buying Websites,” [Online], [Retrieved August 25, 2014],http://www.canstarblue.com.au/retailers/group-buying-websites

Publisher

6.Chang, S. C., Chou, P. Y. & Lo, W. C. (2014). “Evaluation of Satisfaction and Repurchase Intention in Online Food Group-Buying, using Taiwan as an Example,” British Food Journal, 116 (1), 44-61.

Publisher – Google Scholar

7.Chin, W. W. (1998). “The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling,” Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey.

Publisher – Google Scholar

8.Coulter, K. S. & Roggeveen, A. (2012). “Deal or No Deal? How Number of Buyers, Purchase Limit, and Time-to-Expiration Impact Purchase Decisions on Group Buying Websites,” Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 6 (2), 78-95.

Publisher – Google Scholar

9.Cudo. (2014). [Online], [Retrieved August 20, 2014], http://cudo.com.au/info/about-us

Publisher

10.D & B. (2013). “Group Buying Sites on the Rise,” [Online], [Retrieved July 15, 2014], http://goo.gl/w8RdPL, 2013.

Publisher

11.Demangeot, C. & Broderick, A. J. (2010). “Exploration and its Manifestations in the Context of Online Shopping,”Journal of Marketing Management, 26 (13), 1256-1278.

Publisher – Google Scholar

12.Dulleck, U. et al. (2011). “Buying Online: An Analysis of Shopbot Visitors,” German Economic Review, 12 (4), 395-408.

Publisher – Google Scholar

13.Gabler, C. B. & Reynolds, K. E. (2013). “Buy Now or Buy Later: The Effects of Scarcity and Discounts on Purchase Decisions,” Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 21 (4), 441-455.

Publisher – Google Scholar

14.Gefen, D., Straub, D. W. & Boudreau, M-C.. (2000). “Structural Equation Modelling and Regression: Guidelines for Research Practice,” Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4, 1-78.

Publisher – Google Scholar

15.Groupon. (2012). [Online], [Retrieved August 20, 2014], http://www.groupon.com.au/about-us

Publisher

16.Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). “The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing,” Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277-319.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17.Hsu, M. H., Chang, C. M., Chu, K. K. & Lee, Y. J. (2014). “Determinants of Repurchase Intention in Online Group-Buying: The Perspective of DeLone & McLean IS Success Model and Trust,” Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 234-245.

Publisher – Google Scholar

18.Johnson, J., Tellis, G. J. & Ip, E. H. (2013). “To Whom, When, and How Much to Discount? A Constrained Optimization of Customized Temporal Discounts,” Journal of Retailing, 89 (4), 361-373.

Publisher – Google Scholar

19.Kotler, P., Burton, S., Deans, K., Brown, L. & Armstrong, G. (2013). ‘Marketing,’ 9th edn, Pearson, Australia.

20.Liu, X. S., Loudermilk, B. & Simpson, T. (2014). “Introduction to Sample Size Choice for Confidence Intervals Based on t Statistics,” Measurement in Physical Education & Exercise Science, 18 (2), 91-100.

Publisher – Google Scholar

21.LivingSocial. (2011). [Online], [Retrieved August 22, 2014], https://www.livingsocial.com/au

Publisher

22.Ourdeal. (2014). [Online], [Retrieved August 22, 2014], http://www.ourdeal.com.au/about

Publisher

23.PwC. (2014). “Achieving Total Retail: Consumer Expectations Driving the Next Retail Business Model,” [Online], [Retrieved August 28, 2014],

http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/retail-consumer/retail-consumer-publications/global-multi-channel-consumer-survey/index.jhtml

Publisher

24.Scoopon. (2014). [Online], [Retrieved August 21, 2014], http://www.scoopon.com.au/about-scoopon

Publisher

25.Stafford, P. (2012). “Yahoo!7 to Stop Spreets Performance Payments as Group Buying Market Dries up,” [Online], [Retrieved August 28, 2014],

http://www.startupsmart.com.au/technology/yahoo7-to-stop-spreets-performance-payments-as-group-buying-market-dries-up/201204166010.html

Publisher

26.Statista. (2014). “Statistics and Facts about Group Buying in China,” [Online], [Retrieved August 29, 2014],http://www.statista.com/topics/1396/group-buying-in-china

Publisher

27.Taylor, S. (2007). Business Statistics for Non-Mathematicians, 2nd edn, Palgrave McMillan, UK.

Publisher – Google Scholar

28.Wibowo, S. & Grandhi, S. (2014). “A Performance-Based Approach for Assessing the Quality of Group Buying Websites,” Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on Information Science and Technology, 26 – 28 April 2014, Shenzhen, China.

Publisher – Google Scholar

29.Yuan, S. T. & Lin, Y. H. (2004). “Credit Based Group Negotiation for Aggregate Sell/Buy in E-Markets,” Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 3, 74-94.

Publisher – Google Scholar

30.Zhang, X., Williams, A. & Polychronakis, Y. E. (2012). “A Comparison of E-Business Models from a Value Chain Perspective,” EuroMed Journal of Business, 7 (1), 83-101.

Publisher – Google Scholar