Introduction

These last years, the child was in the center of the Marketer’s concerns and became the most desired consumer. Indeed, children became the main influencers for 80 % of toys, 75 % of cereal, 73 % of dairy products, 69 % of biscuits, 66 % of chocolate bars and 61 % of clothes (IED, 2005). By 1994, the child influenced 43 % of family’s purchases.

The abundance of products makes it necessary to work the legibility on the shelf space and to opt for the seduction by betting for example on the charm, on the emotion or by making packaging a communication tool. Addressing the child is necessary to choose simple representations.

Various studies show that children are endowed with low cognitive capacities in particular in terms of data processing and memorization but that they are more attracted by the images. So, the visual aspect is considered as being a determining element in attracting the children and to be successful in easily storing the product and being easily recognized (Rossiter, 1975; Horowitz, 1978; Guiminel-Branca, 1991; Brée and Cegarra, 1994). By targeting children between 4 and either 9 or 10, packaging or advertising are strengthened by the presence of a character to facilitate the understanding and memorization of the message by the child. Indeed, according to Garnier and Guingois (2001) “at three years old, we love the characters and the drawings on products or clothes, because we become identified with them. In 6 years, we play with the characters, we want to find them everywhere. In 10 years, the brands replace the characters”.

Executive Frame

Brée and Cegarra (1994) show the importance of using characters to facilitate the recognition of the product by children. Since then, several works were realized in particular by Callcott and Lee (1995), Callcott and Phillips (1996), Phillips (1996) and Hémar-Nicholas (2008; 2009 and 2011). Indeed, “when we address to the children, we are almost obliged to turn in the direction of a character because its use is hardly requested to arouse the interest of the children” (Brée and Cegarra, 1994). Nevertheless, no study was interested to scrutinize the attitude of the children to the brand characters and to see its impact on the prescription.

The objective of this research is twofold. The first one is to dread the impact of the characteristics of the brand character and those of the child on his/her attitude to the brand character and on his/her identification of the brand character. The second is to seize the prescription.

So, the researchers try to model the child prescription by integrating the child’s attitude and identification to the brand character as mediating variables.

The Determiners of Child’s Prescription

Importance of the Type of the Communication in the Relation Child-Mother

The child’s socialization passes in transit through the communication between the parents and the children. New Comb (1953) and Mc Leod and O ‘ Keefe (1972) presented a typology of families based on the structure of the communication parents – child namely: the social orientation and the abstract orientation.

Carlson and Grossbart (1988), then Carlson, Grossbart and Stuenkel (1992) proposed a model which is close to that of Baumrind (1978) based on two categories of parents: the “authoritarian”: those who make a commitment through actions on media (control broadcast emissions viewed by their children) and the “tolerant”: those who favor the discussion, even if the control persists.

They showed the existence of a positive relation between the child’s influence and the family’s types. Indeed, they were able to kick away four types of family:

“The democratic” : those who are attuned to their children. In these families, the power of prescription is important for products limited by parents.

“The tolerant” : the child is considered the king with a real parental control, the prescription is more important even for domains not specific to the children.

“The disengaged”: they are distant and slightly worry about their children, the prescription is averagely important in these families.

Finally, “the autocrats” : they require respect for a whole set of rules, the prescription is of this low fact. Our hypothesis will be the following one: the success of the prescription depends on the type of family.

The Product’s Type Affects the Prescription Child-Mother

The type of product was considered the first cause of variation of the children’s influence. Wells and Lo Sciuto (1966) showed that there is a positive correlation between the degree of influence exercised by the child and the nature of the product. So, the influence varies according to the child being the user of the product or not. Ward and Wackman (1972) demonstrate that the child has a considerable influence on products intended for his own use but unimportant for others. This result was confirmed by Mangleburg (1990), who proved the existence of a correlation between the influence of the child and its level of implication to the product.

Several authors (Belch, Belch and Ceresino, 1985; Foxman and Tansuhaj, 1988; Moschis and Mitchell, 1986) showed that this influence is sharply more restricted for products used by the family. Nevertheless, other studies proved that the child has a very strong influence on the decisions relative to the choice of the place of the holidays (Nelson, 1979; Szybillo and Sosanie, 1977; Darley and Lim, 1986). Our hypothesis is the following: the child’s prescription depends on the nature of the product.

Role of the Symbolic Characters in the Prescription Child-Mother

The Role of the Symbolic Characters in the Relation Child-Brand

The brand characters are “small characters met on packaging as mascots should be able to live outside the packaging and convey the product’s attributes” Chastellier (2003).

For Cegarra and Brée (1993), the characters are communication tools. They play a role of visual coding and symbolic representation of the brand, especially directed to children. By using a symbolic character, the brand will be more accessible, more understandable and more alive for the child through creating a real relation with him. The character will be the translation of the brand on a register which makes possible a complicity, a real one, with the child (Montigneaux, 2002). So, the character is considered the spokesman of the brand. It has to create an emotional relation and facilitate the exchanges between the brand and the child.

The symbolic character has a cognitive function because at first, it allows to identify the brand and the product. It is considered a mark in the middle of all the messages conveyed by the brand. Secondly, it allows informing the child about the quality of the product. Finally, it permits a conditioning and learning of the brand by the child (Brée and Cegarra, 1994; Mizerski, 1995).

The emotional dimension occupies an important place in all that the child undertakes altogether (Kapferer, 1985; Brée, 1993; Derbaix and Brée, 1997; Pecheux, 2001). Indeed, the emotional dimension conditions directly the capacity of the child to receive the cognitive exchanges of the brand. The emotional function of the characters is based on the identification process (Brée and Cegarra, 1994). This emotional relation between child and brand character is based essentially on the characteristics of the latter.

The Child’s Attitude towards the Brand Characters

Brée and Cegarra (1994) realized an exploratory study concerning the recognition and the memorization of the child of the characters, which remains until our days an innovative study. They underlined, on the one hand, the importance of the study of the child’s attitude to the brand characters. They present this as an “emotional score “: a global emotional appreciation assigned to the character. The more favorable attitude of the child towards the character, the more effective is the role of the catalyst of the cognitive performances. Indeed, the attitude of the child to the character could influence the impact of the character on the memorials processes of the child. So, even a young child would be capable of reminding himself of a brand if he appreciated the character.

On the other hand, Brée and Cegarra (1994) argues that the qualitative elements of the commercial dimension (staged, the minor characters) and the characteristics of the character (morphological and of personality) can create a favorable emotional link between the child and the character in question (Montigneaux, 2002; Hémar-Nicolas, 2007). In other researches, it seems that the favorite characters of the children depend on the age and sex of the child (Chombart of Lauwe and Bellan, 1979).

Recently, Hémar-Nicolas (2008) has been interested in the study of the link between the child’s attitude towards the leading character and the familiarity with this character. She suggested measuring the child’s attitude to the symbolic character with an iconic scale for two items, through the distribution of candies to the leading character according to the child’s appreciation of the character. The results were mitigated because there was an absence of strong correlation between both measures which can be understandable by the difficulty of working with young children. Then in 2009, Hémar-Nicolas tested the link between the presence of a symbolic character on the packaging and the child’s intention to ask for the brand. The experiment allowed the child to show that even if the child is capable of associating the character with a brand, it does not imply forcing its intention to ask for it.

Consequently, until now there is a limited knowledge of the explanatory factors of the child’s attitude to the brand character and its impact on the prescription child-mother. The following hypothesis is therefore formed: the more the child’s attitude is favorable to the brand character, the more the product will be prescribed.

The Child’s Identification to the Brand Character:

The identification “is the process to become fully or partially similar to another one”. The child is going to admire this character for its physical characteristics and its personality. We come out to two types of identification: in the third identification the similarity between the child and the brand character drives the child to get closer to it. In the specular identification, the character is perceived as the child’s image, this one considers it as his “alter ego”.

So, the emotional relation between the child and the symbolic character is based essentially on the characteristics of the latter. Hence, the following hypothesis has emerged: the more the child will become identified with the brand character, the more the product will be prescribed.

The Determiners of the Child’s Attitude and the Child’s Identification of the Brand Character

Role of the Behavioral Variables

– The Effect of the Morphological Characteristics of the Brand Character on the Attitude and the Identification of the Child of the Brand Character

The characters are diagrammatically represented in view to serve as a sign. They play the role of support of several stereotypes conditioning its behavior and returning it as much as possible in compliance with the models known by the child (such as the sportsmen, the gentiles, the cunning). Indeed, the morphological characteristics of the symbolic characters have a very important impact on the children. Characters of Disney were analyzed by Antier (1998), on the plan morphological psychology, and the results are edifying: the child is alone capable of recognizing them. So, the children are capable of defining the personality of its characters. Curves can be regarded as a brand of the generosity of the character (Mickey); on the other hand, jagged forms can convey certain aggressiveness (Pokémon).

These results were confirmed by Montigneaux (2002). Indeed, by describing a character, Montigneaux divides the body into two parts: the intellect (the part above the belt) and the instinct (the bottom of the body). So, the personality of the character is going to depend on the dominance of one of these two parts on the other one. If the top dominates, the character is pensive (Smacks); if the bottom dominates, the character is impulsive (Groquik). It is necessary to know that at this age the children face a difficulty in encircling the personality of the characters they admire.

So, the researchers suggest studying the following hypothesis: “the attitude and the identification of the child vary according to the morphological characteristics of the brand character”.

– Impact of the Characteristics of Personality on the Child’s Attitude to and Identification of the Brand Character:

The character is described and analyzed by the child as a real person. The character should be a part of the child’s world and it consequently has to have good relations with the child. Brissy (1996) noticed that the children from 7 to 8 years old follow a certain sequence to describe the brand characters. They begin by describing the physical features, then the attitude and finally the personality of the character. A study realized by Reason why Kid (1992) made possible defining the most appreciated personality’s features by the children: ” The character is funny, nice “,” the character accompanies the child “and” the character opens its imaginary universe”.

From their young age, the children are sensitive to and admiring of the characters who are strong, fast and graceful. They are filled with admiration for the physical attributes which denote a certain “intelligence” of the body.

Through their works, Chombart de Lauwe and Bellan (1979) show that there is a adult-and-child double polarity at the character. So, if the grown-up pole dominates, the character is “an adventurer” such as Captain Choc, Prince, Yoco… On the other hand, if the child pole dominates, we shall be in the presence of the “sociable” type (Quicky). It is through the proposal of a model of behavior by the character in the child that the process of identification can take place. Little by little, the character is going to guide the child to adult status. The hypothesis including this relation is the following: «the child’s attitude and identification vary according to the personality of the brand character”.

Role of the Socio-Demographic Variables of the Child

-Impact of The Age on the Child’s Attitude and Identification of The Brand Character

The child’s age plays an important role in the understanding of the child’s behavior. Indeed, several authors (Case, 1974; Belk, Mayer and Driscoll, 1984; Selman, 1980; Roedder, 2001) tried to analyze the capacities of the child to understand and to treat information. By analyzing the variation of the child’s perception of the character according to its age, the existence of four stages is noticed:

- From 0 to 3 years: it is the age of concrete and material representation of things. Because of his limited capacities the child is unable to dissociate between the product, the brand and the character. The emotional dimension will dominate.

- Between 4 and 9 years: it is the age of imagination, the character attract children through the imagination which is going to lead to child’s future plan projection. – From 9 years, the character asserts itself: the children are capable of elaborating complex operations on concrete objects. They do not become identified any more with the characters soft and polish, and look for more characters who convey signs of membership in peers. – From 11 to 13 years, the character takes a more statutory shape: the children are capable of understanding abstract thoughts. The functions of memorization and recognition (cognitive functions) are going to override the emotional functions: the child’s relation with the brand character will lose its intensity.

So, the links between the child’s attitude towards the brand character, the child’s identification of the brand character and the age of the child will be analyzed thanks to the following hypothesis: «the child’s attitude to and identification of the brand character depends on the age of the child”.

– Effect of the Character’s Sex on the Child’s Attitude to and Identification of the Brand Character

Chombart de Lauwe and Bellan (1979) tried to distribute choices among 1046 children from 8 to 12 years old according to the sex of the character. So, the male character was chosen by 95 % of the boys and 46 % of the girls. Pursuing their investigation, they noticed that when they ask the children with which character they become identified, the children appreciate more a character of the same sex. The hypothesis including this relation is the following: «the child’s attitude to and identification of the brand character vary according to the sex of the child”.

Presentation of the Explanatory Model of the Prescription Child-Mother Integrating the Attitude and the Identification of the Child to the Brand Character

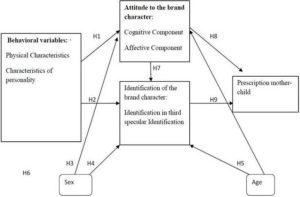

The review of the presented literature allows proposing the model following on the relation between the child’s attitude and identification towards the brand character and the prescription child-mother (figure 1). Indeed, several studies showed that the child’s prescription depends on the nature of products and on the exchanges of communication within the family. Nevertheless, few researchers were interested to study the impact of the brand characters on the child and consequently on his prescription. We suggest analyzing the relations between the use of the brand characters and the prescription.

This model summarizes all the hypotheses formulated in the previous paragraphs. So, once the child perceives positively the morphological and psychological characteristics of the brand character, the child will have a favorable attitude to this character and the product will be prescribed. The more the child’s attitude will be strong, it will become identified with the symbolic character and the more the prescription will be important. On the other hand, the socio-demographic characteristics can affect at the same time the child’s attitude to the brand character but also his identification. Indeed, the child’s attitude to and identification of the brand character depend on the age and sex of the child. Both attitude and identification t are considered as mediating variables of the prescription child-mother.

Represent 1-Explanatory Model of the Prescription Child-Mother Integrating the Child’s Attitude and Identification of the Brand Characters as Mediating Variables

Conclusion

The specific objective assigned to this study is to propose a preliminary explanatory model allowing better explanation of the relation between the prescription child-mother and the child’s attitude to and identification of the brand characters, while trying to integrate on one hand the morphological and the personality variables of the brand character and on the other hand the socio-demographic variables of the child occurring in this relation and developed in the literature. We integrated the other variables in particular the category of products and the relation child-mother to explain better this prescription.

By studying the effects of the child’s attitude to and identification of the brand characters occurring in the child-mother prescription, our ambition is to enrich the theory of modeling the consumer purchasing behavior, particularly that of the child. In our knowledge, no research in marketing studied the effect of the child’s attitude to the brand characters and the effect of the child’s identification of the brand character on the child-mother prescription.

Let us underline that this work is unfinished because: – we suggest, first of all, building a measure scale of the child’s attitude to the brand character and the child’s identification of the brand character by applying paradigm of Churchill (1979) and by adapting it to the limited cognitive capacities by this last one. – Our ambition, secondly, is to test this global model by the method of the structural equations models to verify its admissibility.

However, even at this stage, we hope to contribute to the research in marketing generally, and in child behavior particularly. However, in spite of the contribution concerning the theoretical anchoring of the model, several questioning deserve to be put, and considered as future ways of research: the degree of understanding by the child of the message conveyed by the symbolic character; the necessity of integrating the other graphic elements (colors, form, minor characters) into the study of the impact of the character on the child.

References

Aaker, J. L. (1997). “Dimensions of Brand Personality,” Journal of Marketing Research, 34, 347- 356.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Antier, E. (1998). Pourquoi Votre Enfant Est Fan De Disney?, Edition Hachette.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Baumrind, D. (1978). “Parental Disciplinary Patterns and Social Competence in Children,” Parental Disciplinary Patterns and Social Competence in Children, Youth and Society, N° 9, 239 –276.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Belch, G. E., Belch, M. A. & Ceresino, G. (1985). “Parental and Teenage Child Influence Family Decision Making,” Journal of Business Research, 13(2), 163 – 176.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Belk, R., Mayer, R. & Driscoll, A. (1984). “Children’s Recognition of Consumption Symbolism in Children’s Product,” Journal of Consumer Research, 10, 386-397.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Berey, L. A. & Pollay, R. W. (1968). “The Influencing Role of the Child in Family Decision Making,” Journal of Marketing Research, 5, 70-72.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Brée, J. (1993). ‘Les Enfants La Consommation et Le Marketing,’ Paris, Edition Presses Universitaires De France.

Google Scholar

Brée, J. & Cegarra, J. J. (1994). ‘Les Personnages, Eléments de Reconnaissance des Marques Par Les Enfants,’ Revue Française du Marketing, 146, 21.

Google Scholar

Brissy, O. (1996). Alice Au Pays des Marques. Sens, Fonctions et Mémorisation de La Marque Chez Les Enfants de 7/8 Ans, Diplôme D’études Approfondies En Sciences de L’information et de La Communication, Université de Paris IV Sorbonne, Paris.

Calcott, M. F. & Lee, W. N. (1995). “Establishing the Spokes-Character in Academic Inquiry: Historical Overview and Framework for Definition,” Advances In Consumer Research, 22, 144-151.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Calcott, M. F. & Phillips, B. J. (1996). “Observation: Elves Make Good Cookies: Creating Likable Spokes- Characters Advertising,” Journal of Advertising Research, 36 (5), 73-79.

Publisher

Carlson, L. & Grossbart, S. (1988). “Parental Style and Consumer Socialization of Children,” Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (1), 77- 94.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Carlson, L., Grossbart, S. & Stuenkel, J. K. (1992). “The Role of Parental Socialization Types on Differential Family Communication Patterns Regarding Consumption,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, 1(1), 31- 52.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Case, R. (1974). “Structure and Structure: Some Functional Limitations on the Course of Cognitive Growth,” Cognitive Psychology, 6,571-607.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Chastellier, R. (2003). Marketing Jeune, Edition Village Mondial.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Chombart De Lauwe, M. J. & Bellan, C. (1979). ‘Enfants de L’image,’ Edition Payot.

Google Scholar

Darley, W. F. & Lim, J. S. (1986). “Family Decision Making in Leisure-Time Activities: An Exploratory Investigation of the Impact of Locus of Control, Child Age Influence Factor and Parental Type of Perceived Child Influence,” Advance in Consumer Research, 13, 370 – 374.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Derbaix, C. & Brée, J. (1997). “The Impact of Children’s Affective Reactions Elicited by Commercial on Attitudes toward the Advertisement and the Brand,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14, 207-229.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Derbaix, C. & Pecheux, C. (1999). “Mood and Children: Proposition of a Measurement Scale,” Journal of Economic Psychology, 20 (5), 571-591.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Derbaix, C. & Pecheux, C. (2000). ‘Des Outils Pour Comprendre L’enfant-Consommateur : Bilan De 5 Années De Recherche,’ Proceedings of the Xvième Congrès International De l’Association Française Du Marketing, Montréal,19-20 May.

Google Scholar

Derbaix, C. & Pecheux, C. (2003). “A New Scale to Assess Children’s Attitude toward TV Advertising,” Journal of Advertising Research, 43, 390-399.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Foxman, E. R. & Tansuhaj, P. S. (1988). “Adolescent’s and Mother’s Perceptions of Relative Influence in Family Purchase Decisions: Patterns of Agreement and Disagreement,” Advance in Consumer Research, 15, 449 – 453.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Garnier, J. & Guingois, S. (2001). ‘Les Préférées Des Moins De 13 Ans.’ Selon Une Etude Exclusive ABC/Disney Pour LSA, N° 1736, 13 Septembre 2001, P 72- 79.

Guiminel-Branca, A. (1991). ‘Les Enfants et La Fidélité a La Marque, Projet de Maîtrise Réalisé Sous La Direction de BREE J.,’ Université de Paris IX-Dauphine.

Hémar-Nicolas, V. (2007). ‘Le Personnage de Marque: Son Impact Sur La Mémorisation et L’intention de Demande de La Marque Auprès des Enfants Agés de Six a Dix Ans,’ Thèse de Doctorat Es Sciences De Gestion, Université Paris I Panthéon Sorbonne.

Google Scholar

Hémar-Nicolas, V. (2008). “J’aime Quicky ! De La Nécessité, Pour L’enfant, De Connaitre Un Personnage De Marque Pour L’aimer,” Actes Du Xxivème Congrès De l’Association Française Du Marketing, Val De Marne, 15 Et 16 Mai.

Hémar-Nicolas, V. (2009). “Maman, Je Veux Le Shampooing Avec Le Bonhomme ! Le Personnage De Marque Sur L’emballage Déclenche-T-Il Toujours Chez L’enfant L’envie De Réclamer La Marque?,” Actes Du 25e Congrès International De L’afm – Londres, 14 Et 15 Mai 2009.

Publisher

Hémar-Nicolas, V. (2011). “Le Personnage De Marque Sur Le Packaging, Catalyseur De Prescription Enfantine: L’effet Modérateur De La Mise En Scène Du Personnage, De La Familiarité De L’enfant Envers Lui Et Du Niveau Scolaire,” Recherche Et Application En Marketing, 26(4), Pp.23-51.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Horowitz, M. J. (1978). Image Formation and Cognition, New York, Appleton Century Crofts.

Publisher – Google Scholar

IED, (2005). ‘L’Entreprise,’ Novembre 2005.

John, D. R. (2001). “25 Ans De Recherche Sur La Socialisation De L’enfant-Consommateur,” Recherche et Applications En Marketing, 16(1), 89.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Kapferer, J. N. (1985). ‘L’enfant Et La Publicité: Les Chemins De La Séduction,’ Edition Dunod.

Google Scholar

Mangleburg, T. F. (1990). “Children’s Influence in Purchase Decisions: A Review and Critique,” Advance in Consumer Research, 17, 813-825.

Publisher – Google Scholar

MC Leod, J. M. & O’Keefe, G. J. (1972). ‘The Socialization Perspective and Communication Behaviour,’ Current Perspectives in Mass Communication Research, Ed, F.G. Kline Et P.J. Tichenor, Beverly Hills, Sage Publications,121-168.

Mizerski, R. (1995). “The Relationship between the Cartoon Trade Characters Recognition and Attitude toward Product Category in Young Children,” Journal of Marketing, 59,58-70.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Montigneaux, N. (2002). Les Marques Parlent Aux Enfants Grâce Aux Personnages Imaginaires, Editions d’Organisation.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Moschis, G. P. & Mitchell, L. G. (1986). “Television Advertising and Interpersonal Influences on Teenager’s Participation in Family Consumer Decisions,” Advances in Consumer Research, 13, 181 – 185.

Publisher

Nelson, J. E. (1979). “Children as Information Sources in the Family Decision to Eat Out,” Advance in Consumer Research, 6, 419 – 423.

Publisher – Google Scholar

New Comb, T. M. (1953). ‘An Approach to the Study of Commutative Acts,’ Psychological Review, 60, 394-404.

Pecheux, C. (2000). ‘Children’s Reactions to Advertising Communication: Stability and Moderators of the Attitude toward the Ad-Attitude toward the Brand-Behavior Sequence,’ 29th European Marketing Academy’s Conference, Rotterdam, 23-26 May.

Pecheux, C. (2007). ‘Etude De L’enfant-Consommateur: Spécificités Méthodologiques,’ Journée D’étude Sur Le Thème : Ecoute Des Marchés : Méthodes et Résultats, IAE Strasbourg, France, 7 Décembre .

Peirce, K., Mcbride, M. & England, T. (1999). ‘Importance of Gender in Perception of Advertising Spokes-Character Effectiveness,’ Conference of Southwest Texas State University.

Phillips, B. J. (1996). “Advertising and the Cultural Meaning of Animals,” Advances in Consumer Research, 23, 354-360.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Reason Why Kid Ont Réalisé Une Etude Sur La Nature Du Personnage ‘C’est Quoi Un Personnage?,’

Rossiter, J. D. (1976). ‘Visual and Verbal Memory in Children’s Product Information Utilization,’ Advances in Consumer Research, 3, 523- 528.

Google Scholar

Selman, R. L. (1980). The Growth of Interpersonal Understanding: Developmental and Clinical Analyses, New York, Academic Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Semprini, A. (1992). ‘Le Marketing De La Marque: Approche Sémiotique,’ Editions Liaisons.

Google Scholar

Serraf, G. (1978). “Prescripteurs et Relais D’influence,” Revue Française Du Marketing, 4(75), 23- 36.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Szybillo, G. J. & Sosanie, A. K. (1977). “Family Decision Making: Husband, Wife and Children,” Advance in Consumer Research, 4, 46 – 49.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Valette-Florence, R. & Ferrandi, J. M. (2002). ‘Mesure De La Personnalité De La Marque,’ Recherche et Applications En Marketing, 17(3).

Ward, S. & Wackman, D. B. (1972). “Children’s Purchase Influence Attempts and Parental Yielding,” Journal of Marketing Research, 9 (3), 316-319.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Welles, W. D. & Lo Sciuto, L. A. (1966). “Direct Observation of Purchasing Behaviour,” Journal of Marketing Research, 3, 227-233.

Publisher