Introduction

Today, the manufacturing industry worldwide has become a fast-paced industry. Global competition, technological advancement, greater customer expectations, and shorter product life cycles, have increased the need for manufacturing firms to create and deliver value to its stakeholders, particularly its customers. Besides, the recent downturn in the global economy has significantly increased the costs of production and reduced product demands, all of which has urged manufacturing companies to revisit the fundamental driver of their survival. Under such circumstances, it becomes imperative for these companies to reinvent themselves. One way to do so is through innovation.

Innovation has been viewed as one of the key factors underlying a firm’s long-run competitive advantage (Corso, Martini, Paolucci & Pellegrini, 2001; Du Plessis, 2007). According to Lagrosen (2005), new markets and growth possibilities can be created via innovation. Basically, innovation is conceived to encompass the generation, development, and implementation of new ideas or behavior (Damanpour, 1991). Two common forms of innovation within the manufacturing arena relates to product innovation and process innovation. Product innovation generally involves the introduction of new products or services to meet market needs (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001). Process innovation, on the other hand, refers to the implementation of a new significantly improved production or delivery method, which includes changes in techniques, equipment and/or software (Bi, Sun, Zheng & Li, 2006). These two forms of innovation are usually categorized as technological innovation (Chuang, 2005; Cooper, 1998; Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001).

The importance of innovation is widely acknowledged in many studies (Dewar & Dutton, 1986; Gloet & Terzioski, 2004; Kimberly & Evanisko, 1981; Lundvall & Nielsen, 2007). Along with these studies, a range of promising antecedents have been identified. Some authors (Damanpour, 1991; Damanpour, Szabat, & Evan, 1989) have categorized these factors under three categories: individual, organizational, and environmental. Of these, organizational attributes have been argued to be an important determinant of innovation (Kim, 1980). A review of the literature indicates that many of these studies were Western-based such as from the United States and Europe (Damanpour, 1991; Damanpour et al., 1989; Kimberly & Evanisko, 1981; Lundvall & Nielsen, 2007; Miller & Friesen, 1982). Although a wide-range of organizational variables have been examined, knowledge management has been found to have a great influence on innovation and performance (Casvugil, Calantone & Zhao, 2003; Darroch & McNaughton, 2002; Gloet & Terziovski, 2004; Lundvall & Nielson, 2007).This is because knowledge inspires organizational learning which serves as a prerequisite for innovation (Du Plessis, 2007; Gloet & Terzioski, 2004). In addition, organizations that have been effective in managing their knowledge view knowledge as a valuable resource and possess norms and values that support the acquisition, sharing and application of knowledge among their employees, all of which are needed for innovation activities (Davenport & Prusak, 1998).

According to Zheng (2005), knowledge management effectiveness comprised of three components: knowledge acquisition effectiveness, knowledge sharing effectiveness, and knowledge application effectiveness. Zheng (2005) further argued that these three components would have a profound effect on innovation. While many scholars (Darroch & McNaughton, 2002; Du Plessis, 2007; Gloet & Terziovski, 2004; Lundvall & Nielson, 2007) have reported various aspects of knowledge management as antecedents of innovation, these studies have concentrated on innovation in general. Therefore, there is a need to distinguish the different types of innovation since each type of innovation do not have identical attributes (Damanpour, 1987) and may probably involve different predictors (Darroch & McNaughton,2002; Lin, 2006).

Despite the fact that Malaysia is trying to increase its innovative capability in its bid to become a knowledge-based nation, research on innovation practices in its manufacturing firms remains under-researched (Ismail, 2005; Mohamed, 1995; Wan Jusoh, 2000; Zain & Rickards, 1996). With this in mind, the goal of this study was to examine the effect of knowledge management effectiveness (which consists of knowledge acquisition effectiveness, knowledge sharing effectiveness, and knowledge application effectiveness) on technological innovation (comprising of product innovation and process innovation) within the Malaysian manufacturing sector.

Literature Review

Product Innovation and Process Innovation as Types of Technological Innovation

Innovation generally implies the adoption of an idea or behavior which is new for the organization (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001). Innovation can be in the form of a new product or service, a new production process technology, a new structure or administrative system, or a new plan or program pertaining to organizational members (Damanpour, 1991). Past scholars have identified various forms of innovation. For instance, Damanpour (1992) classified six types of innovation namely product, process, administrative, technical, radical and incremental in his study on the relationships. Mavondo, Chimhanzi, and Stewart (2003), on the other hand, categorized innovation into three types: product innovation, process innovation, and administrative innovation. Meanwhile, other researchers (Chuang, 2005, Damanpour & Evan, 1984, Damanpour et al., 1989) have identified two distinct types of innovation: technological innovation and administrative innovation. Of the various types of innovation that have been studied, technological innovation is important for manufacturing firms because it has the capacity to improve performance, solve problems, add value, and create competitive advantage (Cooper, 1998). According to Bi et al. (2006), manufacturing companies have to rely on strong technological innovation in order to produce high-end products. Technological innovation relates to the modifications of existing products and processes based on single or multiple technologies (Roberts, 2007; Bi et al., 2006). Product innovation and process innovation have been popularly viewed as two important dimensions of technological innovation (Chuang, 2005; Cooper, 1998; Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001).

Product innovation encompasses the introduction of new products or services to meet the needs of the external user or the needs of the market (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001; Knight, 1967). According to Hage and Hollingsworth (2000), product innovation, also known as product development, refers to a systematic work process, drawing upon existing knowledge gained from research and practical experiences directed towards the production of new materials, products and devices, including prototypes. Meanwhile, traditionally, process innovation has been viewed as a new way of combining physical inputs, such as labor, equipment, and material, to produce products or provide services (Shaw, 1961). Later, Bi et al. (2006) defined process innovation as the implementation of a new significantly improved production or delivery method, which includes changes in techniques, equipment and/or software.

Knowledge Management Effectiveness

Many scholars have sought to define knowledge management which still continues to be an elusive construct. For instance, Wigg (1997) viewed it as a set of activities that guides a firm in acquisition of knowledge from both inside and outside the company. Knowledge management is regarded as a management discipline which focused on the development and usage of knowledge to support the achievement of strategic business objectives (Ralph, 2003). In an attempt to expand the knowledge management discipline, Darroch and McNaughton (2001) defined knowledge management as the management functions that encompasses the creation of knowledge, management of the flow of knowledge within the organization, and usage of knowledge in an effective and efficient manner for the long-term benefit of the organization. Since the process of innovation depends heavily on knowledge as argued by Gloet and Terzioski (2004), a firm should effectively manage its knowledge. This means that knowledge management effectiveness is instrumental in fostering innovation.

Based on the views of Gold, Malhotra, and Segars’s (2001) as well as Alavi and Leidner (2001), knowledge management effectiveness can also be analyzed from a process perspective. A review of the literature illustrates that knowledge management has three common dimensions: knowledge acquisition or knowledge generation (Gold et al., 2001; Shapira, Youtie, Yogeesvaran & Jaafar, 2006; Yang, 2005), knowledge sharing or knowledge transfer (Choi, 2000; Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000; Murray, 2003; Ralph, 2003; Weber & Weber, 2007), and knowledge utilization or application (Gold et al., 2001; Zheng, 2005). Hence, for innovation to take place, an organization needs to be effective in these three components.

Knowledge Management Effectiveness and Technological Innovation

The knowledge-based view of the firm recognizes the organization as the key element in the creation and application of knowledge (Grant, 1997; Nonaka, 1994). Based on this theory, differences in organizational performances are due to their different capabilities in developing and deploying knowledge. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) argued that there is a need to understand how organizations create and manage new knowledge. The need to pursue ways to create and derive value from knowledge assets within the organization concurs with the argument by Jennex and Olfman (2004) that the effective management of knowledge is expected to strengthen organizational capability to innovate.

As previously mentioned, the success and survival of firms depends heavily on their ability to innovate. In the manufacturing context, increasing competition has led firms to focus heavily on its operational excellence and product leadership by pursuing strategies to actively and explicitly manage knowledge (Wigg, 1997). They need to ensure that they acquire, share, and use the best possible knowledge in all areas of work. In addition, they need to embed the knowledge in their products as well as their internal operations with the aim of creating innovative products and controlling production costs.

Findings from past studies have shown that the creation and management of new knowledge correlated positively with new product development (Madhavan & Grover, 1998; Un & Cuervo-Cazurra, 2004) and new process improvement (Gloet & Terziovski, 2004). This indicates that knowledge management effectiveness represents a firm’s crucial capability that serves as the primary driver of product innovation and process innovation. Since effectiveness of knowledge management entails effectiveness of the three dimensions of knowledge management, we would expect effectiveness in each dimension would lead to the two forms of innovation. Therefore, our main hypotheses are constructed as follows:

H1: Knowledge management effectiveness will be positively related to product innovation.

H2: Knowledge management effectiveness will be positively related to process innovation

The Relationship Between Knowledge Acquisition Effectiveness and Product Innovation and Process Innovation

Knowledge acquisition also known as knowledge generation refers to the process in which knowledge is acquired by an organization from outside sources and those created from within (Davenport & Prusak, 1998). Generally, knowledge and opportunities sourced from a firm’s business partners (such as customers and suppliers) are not only stored as information for the next-generation product development, but also provides valuable prospects for product innovation within a product life cycle (Chapman, O’Mara, Ronchi & Corso, 2001). Hence, knowledge acquisition help ensures the smooth development of new products by the firm. When companies are effective in their acquisition of knowledge from external sources especially specialized knowledge, they are likely to increase their innovative capabilities, enabling them to generate new and unique products. Using past literature (Chang & Lee, 2007; Darroch & McNaughton, 2002; Ignatius, Jantan, & Ramayah, 2004; Yang, 2005; Zheng, 2005) as our guide, the following sub-hypothesis is forwarded.

H1a: Knowledge acquisition effectiveness will be positively related to product innovation.

The effectiveness of knowledge acquisition can be viewed from two perspectives: (1) creation of new knowledge from the application of existing knowledge, and (2) improved usage of existing knowledge and more effective acquisition of new knowledge (Gold et al., 2001). In general, knowledge needs to be acquired in order to solve many problems associated with the manufacturing process, such as slow process techniques, high material consumption, and poor machine quality (Bi et al., 2006). In this regard, companies that are effective in acquiring knowledge from the application of existing knowledge and/or new knowledge are likely to possess the capability to improve the production process, thereby, fostering process innovation. Consistent with previous literature (Darroch & McNaughton, 2002; Du Plessis, 2007; Yang, 2005), we provide the following sub-hypothesis.

H2a: Knowledge acquisition effectiveness will be positively related to process innovation.

The Relationship between Knowledge Sharing Effectiveness and Product Innovation and Process Innovation

Knowledge sharing is generally referred to as knowledge transfer or knowledge diffusion. It is defined as the process in which knowledge is transferred from one person to another, from individuals to groups, or from one group to another group (Davenport & Prusak, 1998). Knowledge sharing involves organizational members who willingly contributed their knowledge for organizational memory. According to several scholars (Hong, Doll, Nahm & Li, 2004; Hoopers & Postrel, 1999), knowledge sharing relates to the understanding and information communication among team members from the different functions within the firm concerning customer requirements, suppliers’ capacities, and internal capabilities necessary for new product development. However, the main challenge for organization is to effectively share the knowledge associated with product development solutions among organizational members for continuous product innovation (Corso et al., 2001). When companies are effective in sharing their knowledge especially within the organization, circulation of information is likely to be greater, enabling the organization to come up with better products faster. Following past studies (Al-Alawi, Al-Marzooqi, & Mohammed, 2007; Chang & Lee, 2007; Darroch & McNaughton, 2002; Yang, 2005; Zheng, 2005), the following sub-hypothesis is forwarded.

H1b: Knowledge sharing effectiveness will be positively related to product innovation

It is crucial for an organization to effectively capture valuable knowledge and stringing it, making it available for the organization and usage by employees in problem solutions for process innovation (Ralph, 2003). The process of transforming knowledge into an easily accessible form and the process of accessing context specific knowledge for a specific purpose, in particular, improving and solving the process problems will lead to process innovation. If companies are effective in sharing their knowledge within the organization, the circulation of information will be accelerated. This, in turn will help to increase the firm’s process capability and productivity. Based on support from the literature (Du Plessis, 2007; Jang, Hong, Bock & Kim, 2002), our next sub-hypothesis is:

H2b: Knowledge sharing effectiveness will be positively related to process innovation.

The Relationship between Knowledge Application Effectiveness and Product Innovation and Process Innovation

Knowledge application, also known as knowledge utilization or knowledge implementation, refers to the process that is oriented toward the actual use of knowledge (Gold et al., 2001). According to Demarest (1997), knowledge must flow into actions in order for it to be useful and beneficial to the organization. Knowledge application can be viewed from various sources, such as when employees apply the firm’s internal knowledge to their individual and team work, when the organization apply information sourced from suppliers to improve product design, when the firm apply information sourced from customers to design new products and technologies, and when the organization apply information sourced from competitors to benchmark new product developments (Lin, 2006). To ensure successful product innovation, knowledge has to be effectively applied by considering the changes in the firm’s environment (Song, Van der Bij & Weggeman, 2005). Effective knowledge application will create value for the firm since this process will enable the firm to realize its current knowledge and whether there is a need for new knowledge. In this way, companies will be able to update its core competence, leading to greater product innovation. In line with findings from past literature (Bhatt, 2002; Chang & Lee, 2007; Zheng, 2005), we conjecture our final sub-hypothesis as follows:

H1c: Knowledge application effectiveness will be positively related to product innovation.

Effective knowledge application will enable a firm to adjust its strategic directions, solve problems, and improve its conversion process quickly and easily (Gold et al., 2001). The application of knowledge acquired from internal and external sources learning activities are bound to create a platform for carrying out new production processes or improve existing ones. For example, information sourced from a firm’s competitors can be used to benchmark production costs and subsequently re-deploy relevant knowledge and technology into new technologies and processes that are more effective and efficient. As such, companies that are able to effectively apply their knowledge and information are likely to improve transformative capability and functionality, which in turn, will foster process innovation. Following previous literature (Adams & Lamont, 2003; Du Plessis, 2007; Jang et al., 2002), our final sub-hypothesis is:

H2c: Knowledge application effectiveness will be positively related to process innovation.

Based on our discussion of the literature, our research framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Research Framework

Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

Questionnaires were distributed to a total of 674 large manufacturing companies located in six states of Peninsular Malaysia. These states were identified as having a high percentage of innovating companies (Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Malaysia (MOSTI), 2006). The list of companies was obtained from the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM) Directory (2007). Participating firms were given two months to complete the questionnaires. After the stipulated period, 171 useable questionnaires were returned and subsequently analyzed, representing a response rate of 25.4 percent.

Measurement

Our predictor variables comprised of knowledge management effectiveness, which includes knowledge acquisition effectiveness, knowledge sharing effectiveness, and knowledge application effectiveness. Each dimension of knowledge management effectiveness was measured using 5 items adopted from Zheng (2005). A seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) ‘strongly disagree’ to (7) ‘strongly agree’ was used. The mean score for each dimension will serve as our indicator of the level of knowledge acquisition effectiveness, knowledge sharing effectiveness, and knowledge application effectiveness respectively. On the other hand, our criterion variable comprised of technological innovation, which includes both product innovation and process innovation. Each type of innovation was measured using four items adapted from Zhang (2006). A similar seven-point response format was used. An index for product innovation as well as process innovation was computed respectively by using the mean score of the four items associated with each variable. A higher mean score indicates higher innovation for either product or process.

Method of Analysis

Past studies have demonstrated that innovation can be influenced by organizational variables, such as size of organization (Akgun, Keskin, Byrne & Aren, 2007; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2005; Wong, Lee & Foo, 2008), and years in operation (Akgun et al., 2007; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2005). Therefore, to avoid confounding effects, these two variables were controlled in the analyses. We employed the multiple regression technique to test our hypotheses.

Findings and Analysis

Profile of Participating Companies

In terms of states, of the 171 participating companies, 34.6% were from Penang, 26.9% were from Selangor, 13.5% were from Johor (13.5%), 10.1 % were from Perak, 5.9% were from Kedah, with the remaining 4.1% from Kuala Lumpur. With regard to the type of industry, the participating firms came from a vast array of industries: electronics/electrical (24.5%), others (23.4%), fabricated metal product (9.6%), rubber and plastics product (8.0%), textile (5.3%), food and beverages (4.3%), motor vehicles (4.3%), paper and paper products (3.7%), chemicals and chemical products (2.7%), medical and precision (2.1%), recycling (0.5%), and machineries (0.5%). In terms of ownership, the sequence are as follows: 44.7 % of the companies were 100% locally-owned, 35.1% were 100% foreign-owned (35.1%), and 20.2% joint-ventures. The median for firm size (measured in terms of the number of employees) is 500. On the average, the firms have been in operation for 23.1 years.

Mean, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of the Study Variables

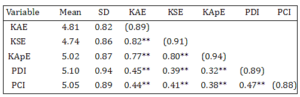

Descriptive statistics (mean scores, standard deviations, reliabilities, and intercorrelations) of the study variables are provided in Table 1.

With reference to Table 1, the responding companies judged their level of product innovation (M=5.10, SD=0.94) and process innovation (M=5.05, SD=0.89) to be relatively high. The level of knowledge application effectiveness (M=5.02, SD=0.87) was found to be slightly higher than knowledge acquisition effectiveness (M=4.81, SD=0.82) and knowledge sharing effectiveness (M=4.74, SD=0.86). The correlations among the knowledge management effectiveness dimensions were statistically significant, ranging from 0.77 to 0.82 (p<0.01). The correlations between the three knowledge management effectiveness dimensions and product innovation and process innovation were also significant, ranging from 0.32 to 0.47 (p<0.01). The reliabilities of the study variables were high ranging from 0.88 to 0.94. According to Sekaran (2003), reliability coefficients that exceeded 0.80 were considered good.

Table1: Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Reliabilities of the Study Variables

Note: Values in parentheses indicate Cronbach’s alpha; KAE denotes Knowledge Acquisition Effectiveness, KSE denotes Knowledge Sharing Effectiveness, KApE denotes Knowledge Application Effectiveness, PDI denotes Product Innovation, and PCI denotes Process Innovation.

Hypotheses Testing

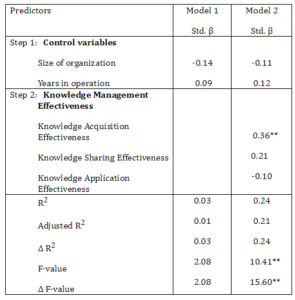

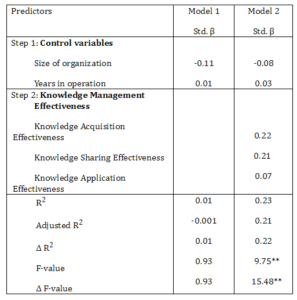

In our study, product innovation and process innovation were regressed separately against the three dimensions of knowledge management effectiveness (knowledge acquisition effectiveness, knowledge sharing effectiveness, and knowledge application effectiveness) respectively in a two-step manner. In the first step, the two control variables were entered into the equation. In the second step, the three dimensions of knowledge management effectiveness were entered. The results of the regression analysis are depicted in Table 2 and Table 3 respectively.

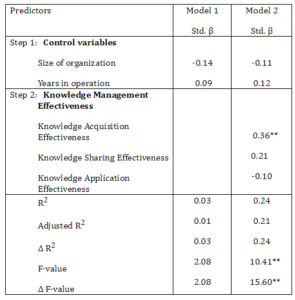

Table 2: Results of Regression Analysis: Impact of KME on PDI

From Table 2, control variables (size of organization and years in operation) explained 3.0% of the variation in product innovation. On adding the three model variables, the R2 increased to 0.24 indicating that the three dimensions of knowledge management effectiveness contributed an additional 21% to the variance in product innovation. The F-change (15.60) was significant (p<0.01). Of the three dimensions of knowledge management effectiveness, only knowledge acquisition effectiveness was found to be positively and significantly related to product innovation (β=0.36, p<0.01), thereby supporting H1a. Both knowledge sharing effectiveness and knowledge application effectiveness had no relationship with product innovation. These results provided partial support for our H1.

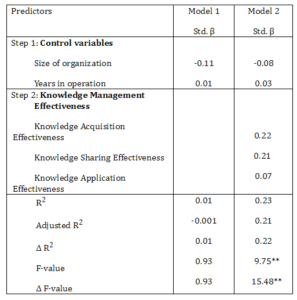

Table 3: Results of Regression Analysis: Impact of KME on PCI

As indicated in Table 3, the two control variables explained only 1.0% of the variation in process innovation. On adding the three model variables, the R2 increased to 0.23 indicating that the three dimensions of knowledge management effectiveness contributed an additional 22% to the variance in process innovation. The F-change (15.48) was also significant (p<0.01). Unexpectedly, all three dimensions of knowledge management effectiveness (knowledge acquisition effectiveness, knowledge sharing effectiveness and knowledge application effectiveness) were unrelated to process innovation. Therefore, our H2 and its sub-hypotheses were unsupported.

Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

Our study sought to examine the effect of knowledge management effectiveness (knowledge acquisition effectiveness, knowledge sharing effectiveness, and knowledge application effectiveness) on product innovation and process innovation. We tested our hypotheses using 171 firms within the Malaysian manufacturing industry. Our results provided partial support for H1 but not H2. Specifically, only knowledge acquisition effectiveness was found to have a significant and positive relationship with product innovation. This finding concurs with past studies (Chang & Lee, 2007; Darroch & McNaughton, 2002; Yang, 2005; Zheng, 2005). When companies are effective in their acquisition of knowledge, they are likely to increase their innovative capabilities, enabling them to generate new and unique products (i.e. greater product innovation). On the contrary, effective knowledge acquisition had no relationship with process innovation. One possible reason may be because process innovation is more internally- focused. In the manufacturing arena, managers need to continuously identify problems and their sources within the production process itself and knowledge acquired internally would enable them to improve the existing process efficiency. In this study, knowledge acquisition entails more of knowledge acquired from external sources, which may not be appropriate for process innovation.

Knowledge sharing effectiveness was found to be unrelated to product innovation and process innovation. In this study, knowledge sharing was judged to be rather moderate. This is expected since Malaysians are known for being unassertive and they value humility (Abdullah, 1992). Thus, organizational members are more likely to be conservative in expressing their ideas and sharing their knowledge. This may have attributed to our non-significant finding. Likewise, knowledge application effectiveness had no relationship with both product innovation and process innovation. One possible explanation for this unexpected finding may be due to the fact that even though participating firms perceived their level of knowledge application to be slightly on the high side, the dynamic environment of the manufacturing sector may have created severe challenges and time pressures that limit the applicability of knowledge for innovative activities (in terms of product and process) within the participating firms. With the recent economic downturn, this finding may be justified.

Our findings offer implications for researchers and practitioners. First, the results provided partial support for the applicability of the knowledge-based view of the firm (Grant, 1997; Nonaka, 1994) within the Malaysian setting. Second, our findings also suggest the need for organizations to acquire knowledge effectively in order to encourage product innovation. One way to do so would be for organizations to encourage their employees to learn by seeking information and feedback from external sources (such as customers, suppliers, retailers) for greater product innovation.

The two main limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, our study makes use of a cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to make inferences regarding causality between knowledge management effectiveness, product innovation and process innovation. A longitudinal approach may be a better option. Second, our sample was rather small and limited to the manufacturing industry alone. Since both forms of technological innovation (product innovation and process innovation) may also prevail in the service sector, replicating a similar study among the various segments of the service industry would improve the generality of the results.

References:

Abdullah, A. (1992), Influence of ethnic values at the Malaysian workplace, Understanding the Malaysian Workforce — Guidelines for the Managers, Abdullah, A. (ed), Malaysian Institute of Management, Kuala Lumpur.

Adams, G.L. and Lamont, B.T. (2003), ‘Knowledge Management Systems and Developing Sustainable Competitive Advantage’, Journal of Knowledge Management, 7 (2), 142-154.

Akgun, A.E., Keskin, H., Byrne, J.C. and Aren, S. (2007), ‘Emotional and Learning Capability and Their Impact on Product Innovativeness and Firm Performance,’ Technovation, 27 (9), 501-513.

Al-Alawi, A.I., Al-Marzooqi, N.Y., and Mohammed, Y.F. (2007), ‘Organizational Culture and Knowledge Sharing: Critical Success Factors,’ Journal of Knowledge Management, 11 (2), 22-42.

Bhatt, G.D. (2002), ‘Management Strategies for Individual Knowledge and Organizational Knowledge,’ Journal of Knowledge Management, 8 (1), 31-39.

Bi, K-X., Sun, D-H., Zheng, R-F. and Li B-Z. (2006), ‘The Construction of Synergetic Development System of Product Innovation and Process Innovation in Manufacturing Enterprises,’ Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Management Science and Engineering (ICMSE), ISBN: 7-5603-2355-3, 5-7 October 2006, Lille, France, 628-636.

Cavusgil, S.T., Roger J.C. and Zhao, Y. (2003), ‘Tacit Knowledge Transfer and Firm Innovation Capability,’ Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 18 (1), 6-21.

Chang, S-C and Lee, M-S. (2007), ‘The Effects of Organizational Culture and Knowledge Management Mechanisms on Organizational Innovation: An Empirical Study in Taiwan,’ The Business Review, 7 (1), 295-301.

Chapman, R.L., O’Mara, C.E., Ronchi, S. and Corso, M. (2001), ‘Continuous Product Innovation: A Comparison of Key Elements across Different Contingency Sets,’ Measuring Business Excellence, 5 (3), 16-23.

Choi, Y.S. (2000), An Empirical Study of Factors Affecting Successful Implementation of Knowledge Management, Published Doctoral of Philosophy Dissertation, University of Nebraska, United States.

Chuang, L-M. (2005), ‘An Empirical Study of The Construction of Measuring Model for Organizational Innovation in Taiwanese High-Tech Enterprises,’ The Journal of American Academy of Business, 9 (2), 299-304.

Cooper, J.R. (1998), ‘A Multidimensional Approach to the Adoption of Innovation,’ Management Decision, 36 (8), 493-502.

Corso, M., Martini, A., Paolucci, E. and Pellegrini, L. (2001), ‘Knowledge Management in Product Innovation: An Interpretative Review,’ International Journal of Management Review, 3 (4), 341-352.

Damampour, F. (1987), ‘The Adoption of Technological, Administrative and Ancillary Innovations: Impact of Organizational Factor,’ Journal of Management, 13 (4), 675-688.

Damanpour, F. (1991), ‘Organizational Innovation: A Meta-Analysis of Effects of Determinants and Moderators,’ Academy of Management Journal, 34 (3), 555-590.

Damanpour, F. (1992), ‘Organizational Size and Innovation,’ Organization Studies, 13 (3), 375-402.

Damanpour, F. and Evan, W.M. (1984), ‘Organizational Innovation and Performance: The Problem of Organizational Lag,’ Administrative Science Quarterly, 29 (3), 329-409.

Damanpour. F. and Gopalakrishnan, S. (2001), ‘The Dynamics of the Product and Process Innovations in Organizations,’ Journal of Management Studies, 38 (1), 45-65.

Damanpour, F., Szabat, K.A. and Evan, W.M. (1989), ‘The Relationship between Types of Innovation and Organizational Performance,’ Journal of Management Studies, 26 (6), 587-601.

Darroch, J. and McNaughton, R. (2002), ‘Examining the Link between Knowledge Management Practice and Types of Innovation,’ Journal of Intellectual Capital, 3 (3), 210-222.

Davenport, T. and Prusak, L. (1998), Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know, Harvard Business Review School Press, Boston, Massachusetts.

Demarest, M. (1997), ‘Understanding Knowledge Management,’ Long Range Planning, 30 (3), 374-384.

Dewar, R.D. and Dutton, J.E (1986), ‘The Adoption of Radical and Incremental Innovations: An Empirical Analysis,’ Management Science, 32 (11), 1422-1433.

Du Plessis, M. (2007), ‘The Role of Knowledge Management in Innovation,’ Journal of Knowledge Management, 11 (4), 1367-3270.

Dyer, J.H. and Nobeoka, K. (2000), ‘Creating and Managing A High-Performance Knowledge-Sharing Network: The Toyota Case,’ Strategic Management Journal, 21 (3), 345-367.

Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers Directory (2007), Malaysian Industries (38th ed.), Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers, Malaysia.

Gloet, M. and Terziovski, M. (2004), ‘Exploring the Relationship between Knowledge Management Practices and Innovation Performance,’ Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 15 (5), 402-409.

Gold, A.H., Malhotra, A. and Segras, A.H. (2001), ‘Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective,’ Journal of Management Information Systems, 18 (1), 185-214.

Grant, R.M. (1997), The Knowledge-Based View of the Firm: Implications for Management Practice,’ Long Range Planning, 30 (3), 450-454.

Hage, J. and Hollingsworth, J.R. (2000), ‘A Strategy for the Analysis of Idea Innovation Networks and Institutions,’ Organizational Studies, 21 (5), 971-1004.

Hong, P., Doll, W.J., Nahm, A.Y. and Li, X. (2004), ‘Knowledge Sharing in Integrated Product Development,’ European Journal of Innovation Management, 7 (2), 102-112.

Hoopes, D.G. and Postrel, S. (1999), ‘Shared Knowledge, “Glitches,” and Product Development Performance,’ Strategic Management Journal, 20 (9), 837-873.

Ignatius, J., Jantan, M. and Ramayah, T. (2004), ‘The Impact of Inter-/Intra-Functional Technological Learning on New Product Development Outcomes,’ Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Engineering Management, ISBN: 0-7803-8519-5, 18-21 October 2004, Singapore, 1023-1027.

Ismail, M. (2005), ‘Creative Climate and Learning Organization Factors: Their Contribution towards Innovation,’ Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26 (7/8), 639-655.

Jang, S., Hong, K., Bock, G. W. and Kim, I. (2002), ‘Knowledge Management and Process Innovation: The Knowledge Transformation Path in Samsung SDI,’ Journal of Knowledge Management, 6 (5), 479-486.

Jennex, M.E. and Olfman, L. (2004), ‘Assessing Knowledge Management Success/Effectiveness Models,’ Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’04), ISBN: 0-7695-2056-1, 5-8 January 2004, Big Island, Hawaii, United States, 1-10.

Jiménez-Jiménez, J. and Sanz-Valle, R. (2005), ‘Innovation and Human Resource Management Fit: An Empirical Study,’ International Journal of Manpower, 26 (4), 364-381.

Kim, L. (1980), ‘Organizational Innovation and Structure,’ Journal of Business Research, 8 (2), 225—245.

Kimberly, J.R. and Evanisko, M. (1981), ‘Organizational Innovation: The Influence of Individual, Organizational, and Contextual Factors on Hospital Adoption of Technological and Administrative Innovation,’ Academy of Management Journal, 24 (4), 689-713.

Knight, K.K. (1967), ‘A Descriptive Model of the Intra-Firm Innovation Process,’ The Journal of Business, 40 (4), 478-496.

Lagrosen, S. (2005), ‘Customer Involvement in New Product Development. A Relationship Marketing Perspective,’ European Journal of Innovation, 8 (4), 424-436.

Lin, Y.C. (2006), The Degree of Knowledge Application, Knowledge Share Mechanism, and Manufacturing Flexibility: An Empirical Study of Technology Companies in Taiwan, Unpublished Doctoral of Philosophy Dissertation, Graduate Institute of Business Administration, National Taipei College of Business, Taipei.

Lundvall, B-K. and Nielson, P. (2007), ‘Knowledge Management and Innovation Performance,’ International Journal of Manpower, 28 (3/4) 207-223.

Madhavan, R. and Grover, R. (1998), ‘From Embedded Knowledge to Embodied Knowledge: New Product Development as Knowledge Management,’ Journal of Marketing, 62 (4), 1-12.

Mavondo, F.T., Chimhanzi, J. and Stewart, J. (2005), ‘Learning Orientation and Market Orientation: Relationship with Innovation, Human Resource Practices and Performance,’ European Journal of Marketing, 39 (11), 1235-1263.

Miller. D. and Friesen. P.H. (1982), ‘Innovation in Conservative and Entrepreneurial Companies: Two Models of Strategic Momentum,’ Strategic Management Journal, 3 (1), 1-25.

Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Malaysia (2006), National Survey of Innovation 2002-2004, Malaysian Science and Technology Information Centre, Putrajaya, Malaysia.

Mohamed, M.Z. (1995), ‘Innovation Implementations in Malaysian Companies: Process, Problems, Critical Success Factors and Working Climate,’ Technovation, 16 (6), 375—385.

Murray, S.R. (2003), A Qualitative Examination to Determine if Knowledge Sharing Activities, Given the Appropriate Media Richness, Lead to Knowledge Transfer and if Implementation Factors Influence the Use of These Knowledge Sharing Activities, Published Doctoral of Philosophy Dissertation, Department of Management and Information Systems, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State.

Nonaka, I. (1994), ‘A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation,’ Organization Science, 5 (1), 14- 37.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995), The Knowledge-Creating Company, Oxford University Press, New York.

Ralph, L. (2003), ‘Knowledge Management and Training: Contradictory or Complementary?’ Training Journal, June, 10-14.

Roberts, E.B. (2007), ‘Managing Invention and Innovation,’ Research-Technology Management, 50 (1), 35-54.

Sekaran, U. (2003), Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pvt. Ltd., Singapore.

Shapira, P., Youtie, J., Yogeesvaran, K. and Jaafar, Z. (2006), ‘Knowledge Economy Measurement: Methods, Results and Insights from the Malaysia Knowledge Content Study,’ Research Policy, 35 (10), 1522-1537.

Shaw, R.J. (1961), A Comparison of Factors Affecting Innovation in Small and Large Firms, Published Doctoral of Philosophy Dissertation, Missouri — Rolla University, Missouri.

Song, M., Van der Bij, H., and Weggeman, M. (2005), ‘Determinants of the Level of

Knowledge Application: A Knowledge-Based and Information-Processing Perspective,’ The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 22 (5), 430-444.

Un, C.A. and Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2004), ‘Strategies for Knowledge Creation in Companies,’ British Journal of Management, 15 (S1), S27—S41.

Wan Jusoh, W.J. (2000), ‘Determining Key Success Factors in New Product Development: Evidence from Manufacturing Companies in Malaysia,’ Journal of International Business and Entrepreneurship, 8 (1), 21-40.

Weber, B. and Weber, C. (2007), ‘Corporate Venture Capital as a Means of Radical Innovation: Relational Fit, Social Capital, and Knowledge Transfer,’ Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 24 (1-2), 11-35.

Wiig, K.M. (1997), ‘Knowledge Management: Where Did It Come from and Where Will It Go?’ Expert Systems with Applications, 13 (1), 1-14.

Wong, P.K., Lee,L. and Foo, D.F. (2008), ‘Occupational Choice: The Influence of Product vs. Process Innovation,’ Small Business Economics, 30 (3), 267-281.

Yang, J. (2005), ‘Knowledge Integration and Innovation: Securing New Product Advantage in High Technology Industry,’ Journal of High Technology Management Research, 16 (1), 121-135.

Zain, M.M. and Rickards, T. (1996), ‘Assessing and Comparing the Innovativeness and Creative Climate of Companies,’ Scandinavian Journal of Management, 12 (2), 109-122.

Zhang, J. (2006), Knowledge Flow Management and Product Innovation Performance: An Exploratory Study on MNC Subsidiaries in China, Published Doctoral of Philosophy dissertation, Graduate School, Temple University, United States.

Zheng, W. (2005), The Impact of Organizational Culture, Structure, and Strategy on Knowledge Management Effectiveness and Organizational Effectiveness, Published Doctoral of Philosophy dissertation, Faculty of The Graduate School, University of Minnesota, United States.