Introduction

At a time when a high quality of life in the office has become a necessity, it is important to reflect on office layout to improve the welfare and performance of employees and enable them to give their best effort. Recent years have witnessed considerable transformation of workspaces that not only depends on the nature of the organization or work but also comes from factors, including globalization, Information Technology and Communication and environmental concerns. The major challenges facing workspace transformation are cost rationalization, activity distribution and flexibility. The harmonization of these spaces has consequences on both the individual and the organization. Indeed, in a continually changing environment, some people may feel confused. According to Linkemer (1999), “the unknown is sometimes disturbing”. The changing nature of jobs has led companies to rethink their organization. Many have come to realize the need for physical locations to be flexible and able to adapt rapidly to changes in activity.

An actor’s physically constrained space refers to an individual’s workspace needs given his body size (Giddens, 1984). This space offers not only esthetic value but also serves as a channel for social relations, monitoring working conditions, employee management, communication, control and hierarchy. From the perspective of the employee at a workstation or behind a desk, the company is constitutes his everyday life. A multitude of facts and symbols have meaning and forms the basis of the employee’s perception of the organization to which he or she belongs (Wacheux, 1997).

By providing a conceptual framework of the literature, this article highlights the relationship between the work environment and its effect within companies. Particular attention should, therefore, be given to the design of offices for improving employee wellbeing.

What are some ways to manage the workspace more effectively? After describing the relationship between individuals and their territory, we will attempt to answer this question by highlighting the importance of space in an organization. We will then describe aspects of work conditions related to space.

The Individual and His Space: A Territoriality Concept

Arriving at a precise definition of space and its role has always been a complex task, particularly in management. Aristotle offered two contradictory definitons in Book IV of Physics (Hayen, 1937). Toward the beginning, Aristotle explains that space and the body form a single component. He later abandons this theory, asserting that the environment (represented by physical space) must be distinguished from the body, which is symbolized by the social activities of the individual (Lefebvre, 1974).

A man establishes with his environment “an integral part of a unique interaction”, in which he interacts with the space to create “a specific cultural product”. Space transforms from being simple physical space to becoming human space. Because the interaction between the individual and space tends to be spontaneous, natural and even unconscious, space has been referred to as the “hidden dimension” (Hall, 1966).

It therefore seems important to investigate the relationship that a man has with his personal space and, more specifically, with his workspace. Before describing this relationship, it seems necessary to first define the concept of territoriality, a concept which fits into the socio-cultural context. The word “territory” comes from Latin jus terrendi, and it means “one who has the right to terrify. The notion of territory is historically tied to issues of power and domination” (Faure, 2006). The Oxford Dictionary (2011) defines territory as the domain a person can appropriate, where he tries to impose or maintain his authority and power. According to Henry Eliot Howard (1920), the notion of territoriality refers to a characteristic behavior adopted by an organization whose goal is to own and defend a territory and prevent members of its own species to invade it. Gustave-Nicolas Fischer (1989) presents the notion of “markers”, which indicate the identity of those who own and occupy the space. Markers are symbols that define the relationship between the self and others. By indicating the ownership of the space (Sommer, 1967; Goffman, 1973), markers serve as a type of prevention and warning to others.

Space is a “social construct” involving a physical arrangement of objects, ownership of these markers and the accuracy of the personal sphere. A given space does not have the same effect across different people. Instead, each person appropriates the space in his own way, based on his feelings, culture, experiences, identity and culture of the place in question. This appropriation may be individual or collective, depending on whether it is made by a person or a group of people.

From these definitions, we can study the concept of “personal space” (Sommer, 1969). Each species has its own social structure and its own ways of exploiting its environment (Hediger, 1955). Personal space is defined as a kind of an “invisible boundary”, a protective zone (Fischer, 1991), a “bubble” (Hall, 1966) or a “sphere” (Goffman, 1973). Through appropriating this personal space, the individual shapes his image, values, and identity (Fischer, 1978). Focuses on himself, the individual controls and organizes his space to share, communicate and interact with others (Maclouf, 2005). Fischer (1989) describes personal space as “an emotional area that varies in size, depending on the psychological and cultural factors, it cannot be penetrated by others without causing defensive reaction”. The principle of territoriality facilitates the management of an individual or a group, to maximize the “use of cognitive maps linking the types of behaviors expected in a given place” and forms the basis of the “personal identity” of the individual or the “social identity” of the group.

Depending on his psychological disposition, an individual may react violently regarding his space. When he senses a certain intrusion, he may become aggressive, threatening or anxious. Irwin Altman (1975) segments the territory into three categories:

- The primary territory is the personal and intimate sphere of the individual, such as home or work space. This is his comfort zone, which should not be disturbed.

- The secondary territory is a semi-private place such as a restaurant.

- The tertiary territory is governed by public institutions with clearly defined rules.

Space should be studied as a whole in terms of several aspects: the ambient environment (physical characteristics such as sound, lighting, ventilation …), the design of the environment (the size of the space, layout, storage …) and the social environment (relationship with others, individual autonomy …) (Lemoine, 2003). The space stimulates the human senses, including sight, hearing, smell and touch.

- The Visual Space: The same space may be perceived in different ways depending on each individual’s culture, beliefs and values. Some details may be essential to a person and neglected by another.

- The Auditory Space: The individual receives and records information from not only the visual space but also the auditory space.

- The Olfactory Space: Amadieu (2005) explains that smell is a factor of exclusion, unlike sight or hearing.

- Space Touch: Hot or cold temperature associated with space (and, in turn, the presence of others) affects an individual’s perception of the space. In fact, the human body is sensitive to small differences in temperature, so the individual will react positively or negatively depending on the thermal conditions of the space in which he is located.

Studying the impact of the environment on the sensory modalities is important for understanding individuals’ reactions to spatial conditions, which shapes his own identity and the relationship he wants with others. To achieve a reasonable level of comfort, proximity should not be burdensome. The mass of people sharing the same space can pose unintended effects on an individual. The individual is sensitive to the size of the space that he inhabits every day.

The workspace is important for professional activity and represents the identity of employees as well as the image and organizational goals of the company (Zarama and Vinck, 2011).

Workspace: An Essential Tool for Management

Choosing and developing a workspace for a company is not a trivial matter. The space presents an image of the organization and is suggestive of company principles and culture. The workspace also allows different actors to interact. Thus, the workspace functions to optimize working conditions, to protect and motivate employees, to enhance well-being and, in turn, individual performance.

As defined by Gustave Nicolas Fischer (1989), the company is a place in which each individual explores, adapts and lives to achieve his personal objectives. Both an emblem and a tool, the organizational space becomes the image of the company (Fischer, 1991). In the words of Tim Davis (1984), this space functions as a “symbolic artifact”.

The space, in terms of both office layout and the architecture of the buliding, is intended as the emblem of the company. Representing both company activity and company values at the same time, the workspace shows whether a company assumes responsibility for its employees’ quality of life at work. According to Tim Davis (1984), the physical environment consists of three main variables that affect voluntary and involuntary management: the physical structure, the physical stimuli and the symbolic artifact. These symbols signal four main messages:

- The design of the environment and conditions of the workspace.

- The status of the employees.

- The employees’ feelings regarding their workload.

- The activities, objectives and image of the organization.

The physical environment has more than a material and a physical dimension; it also has a social and symbolic dimension. In addition to the image and values of the company, space symbolizes the hierarchical position of an individual: employers have large individual offices that are often located on the top floor. Furthermore, space models and shapes social interactions (Goffman, 1973, Hall, 1966; Fischer, 1991), serving as a social construct that promotes informal communication. For example, people may come together and communicate in the hallways or near coffee machines.

The psychology of work has highlighted the importance of studying environmental aspects— a concept that has long been ignored. Research has begun to focus first on physical aspects (e.g., lighting, temperature and noise) as sources of fatigue and absenteeism and, consequently, poor performance. However, similar themes were gradually neglected in the literature about the physical workspace and given more attention in the area of human factors, in which space is considered as a crucial element of organizational efficiency (Fischer, 1991).

Workspace: How to Conceive it?

The nature of work is constantly changing (Chan, Beckman, Lawrence, 2007). A company needs to rethink its workspace to make it more attractive. In particular, the workspace should provide optimal conditions for better performance and enable employees to feel comfortable to collaborate. Employees must not only occupy the space but also adapt the space to their needs.

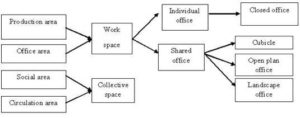

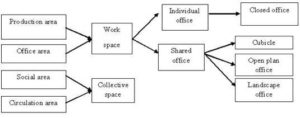

There are four different kinds of space in a company:

- The area of production, which is equivalent to industrial workshops found in primary and secondary sectors.

- The office space for administrative activities.

- The social space (including coffee machines, cafeterias and break rooms), while not directly work-related, allows social interactions to take place between employees

- The circulation areas, such as hallways, are places for the movement of individuals.

The four types of space mentioned above can be further divided into two categories: spaces for work and collective spaces, such as hallways or cafeterias, that are common to everyone. Collective spaces are conducive to informal meetings. Our study concerns the first category, i.e., workspace for bureaucratic tasks.

In terms of the layout of the workspace, the company can choose between two configurations: the individual (or private) office versus the collective (or shared) office. The individual office provides a sense of intimacy and isolation for employees, allowing them to be more productive because they will not be disturbed and distracted by their colleagues. In this case, employees have control over not only their physical workspace but also their psychological workspace.

We have chosen to further study the case of the shared office, which can be considered as a source of competitive advantage due to its flexibility, speed of information flow and economy in terms of space. The shared office may take several forms:

- The cubicle is a mix between a traditional office and a partitioned landscape office. The employee keeps his privacy while being more open to communication with colleagues.

- The open plan office is useful due to its flexibility and transparency. Employees are positioned in rows, allowing a rapid flow of information.

- The landscape office is slightly larger than the open office. It is characterized by the use of plants or storage to replace walls. Such a design creates a fluid, flexible and transparent environment. The flow of information is quick and easy.

Below is a figure that represents the concept of the workspace:

Figure 1: Different Types of Space Configuration

By improving the relationship of colleagues by constantly situating them side-by-side or face-to-face, the shared office encourages innovative performance. However, the shared physical environment can also become a source of stress and conflict among colleagues. Often, employees who share the same space do not belong to the same team. Moreover, constant control creates a climate of tension and the shared space may reduce employees’ ability to concentrate on their work.

From Individual Offices to Shared Offices

The Evolution of the Office:

Alain Chenu (1998) divides the history of the office into three “ages of office work”. The pre-industrial age is characterized by the work of scribes. The industrial age, in the industrial revolution, involved workshops (rather than offices) in which workers, mostly women, worked in rows. The third age is the computer age.

Today, the management tends to be oriented toward results (Taskin, Vendramin, 2004). We hear more and more about open plan offices, mobile offices and telecommuting. While the names are new, similar workspace structures date back to the time of the Pharaohs. In ancient Egypt, scribes were already sharing the same workspace. In ancient Greece, however, “the organizational structures…were different. The offices were separated into two parts: a workspace and a space to discuss or lunch. It is a striking similarity between this form of office and current office: offices today are increasingly equipped with cafeterias, coffee spaces or lounge areas” (Hascher, Jeska and Klauck, 2002 ; Abou Hamad, 2012). Since 1870, many inventions, such as the telephone, lighting, and the typewriter, have facilitated work and increased production. “In Europe, especially following the stock market crash of October 1929, open plan offices became a solution to save space. During the postwar boom, a period of strong economic growth between 1945 and 1975, the office became more flexible thanks to prefabricated elements: one could move from closed to open space and vice versa. During the fifties, the “pool” became the new trend especially with secretaries lined up in rows: the secretaries were working without communicating with each other” (Pélegrin-Genel, 2006; Abou Hamad, 2012).

The open space originates from the Panopticon of Jeremy Bentham (1977). To maintain order in prisons, Bentham developed a central inspection structure such that hundreds of men rely on a single man, giving this one man a kind of universal presence: “The eye the master is everywhere”. The panopticon is “the ability to see at a glance what is happening”. Today, this panoptic principle can be applied to most offices (Martinache, 2011). By enacting this structure in the classroom, Taylor enabled continuous control and non-communicative work.

Various studies on the relationship between employees and the office workspace have shown that open plan offices lead to high levels of satisfaction and motivation with good ergonomic data. In 2008, 73% of employees indicated that the layout of their office was a deciding factor in their feelings about the workplace (according to the meeting of Actineo in Paris on November the 18th, 2008, Should we close the open space?).

The Influence of Spatial Layout on Ergonomics

In addition to posing an impact on work, how does the workspace affect the employee? On the physical dimension, an individual depends on his workspace (Giddens, 1984), but space also presents social constraints that are accepted and internalized in the sense of Durkheim (1930). “The space is valued as a social matrix that determines our forms of life” (Fischer, 1964). This space offers not only esthetic value but also serves as a channel for social relations, monitoring working conditions, employee management, communication, control and hierarchy. Space is no longer a concept but an entity. Employees spend the majority of their day at work.

The goal of ergonomics is to improve the quality of work by adapting the machine to man (Sperandio, 1980). Work is defined as the “person-environment interaction dynamics through an analysis scheme of complex features” (Fischer, 1991). The characteristics of workspace elements such as height, surface or storage must match the ergonomics of the employee who works several hours a day.

It is important and necessary for a company to invest in ergonomics and establish favorable working conditions for employees to protect the health of their employees and the image of the company.

The space must also meet the needs of the employee, as identified by Maslow (1954) and Guerrero (1999). These requirements form the basis for managerial properties of workspaces (Maclouf, 2005):

- Changes in workspaces foster organizational learning when the environment changes. Individuals seek to better understand their new space in the process of developing physical and psychological control. Employees will also develop new relationships with others.

- The workspace makes it easier to manage interactions and relationships.

- The employee seeks to understand his company. Space becomes a cognitive tool that enables a better understanding of the environment.

Maclouf (2005) draws the relationship between the workspace and an individual’s basic needs:

- Biological and Physiological Needs: In the workspace and other contexts, there must be necessary elements to sustain the life of the organization (Maslow, 1954). The space must have the right temperature, an acceptable humidity level, good air circulation, the presence of natural light, and allow opportunities to take breaks in the workplace.

- Safety Needs: Privacy is the ability to isolate oneself from others and addresses a person’s need to protect his individuality (Fischer, 1989). Thus, the space must ensure protection against external intrusion. Demonstrating respect for the minimum interpersonal distances required by individual employees while ensuring stability in the physical layout and allocated space are crucial issues in workspace management.

- Belongingness and Love Needs: Places should allow individuals to connect with each other and belong to a group. The original paradigm of the social space, as described in particular by Moles (1977 – 1984) and Fischer (1989), enables physical gathering while creating opportunities for people to build relationships with others.

- Esteem Needs: Multiple features make the workspace a channel of social hierarchy.

- Self-Actualization Needs: The achievement of personal goals through ownership of a place regardless of the esteem of others.

- Understanding the Needs of the Environment: Perception of the environment and individual cognitive maps (Fischer, 1989). Spaces represent the organization and one’s place in the workflow. For stakeholders to engage in collective action, spaces should be seen as consistent with the organizational project.

- Identification Needs: Actors and stakeholders, in general, need to understand the identity of the organization to contribute to its collective action. Through cognitive processes, workspaces convey a representation of the organization.

- Control Needs (Guerrero, 1999): Workspaces provide players with a level of autonomy, power and control.

Needs identified by Maslow and Guerrero can be combined. Taking employees who eat in the workplace, for example, Etienne Maclouf (2005) proposes that the workspace not only addresses physiological needs but also needs related to belongingness, self-esteem, self-actualization and control.

Working Condition:

From 1924 to 1927, Elton Mayo conducted several experiments at the Western Electric factory in Hawthorne to analyze the effect of physical conditions on worker performance. Mayo found that productivity increased when lighting was increased or reduced, though the light itself did not influence production. Later, this work became controversial, triggering further studies on office lighting. For example, working near a window has been found to have a positive effect on employee satisfaction due to a combination of light intensity and the ability to see outside (Newsham, 2003).

In July 2007, an experiment was conducted in the United States to investigate the effect of light on employees. Among their findings, researchers found a positive correlation between job satisfaction and good lighting (Veitch, Newsham, Boyce, Jones, 2007). In response to ecological behavior, the employer must maximize the use of natural lighting. Similarly, the quality of the light must be good, with the color temperature, color-rendering index lamps and selection of a light adapted to the visual task to avoid the discomfort glare.

Noise affects the physiological and psychological welfare of the individual (Floru and Cnockaert, 1991). Noise affects the whole body and can impact the likelihood of developing cardiovascular and sleep disorders. The effect of noise on behavior depends on the extent of auditory discomfort, the irritability of the individual and changes in social and individual behavior. Noise (coming from continuous office traffic, communication between colleagues and phone ringtones) is one of the primary disadvantages of the open space office. For example, a printer produces 75 decibels (dB) of sound, the phone 70 dB, the ambient office 60 dB (40 dB in a quiet office). In terms of the impact of sound on human functioning, noise poses a risk for hearing at 85 dB, makes work more difficult at 70 dB and makes intellectual labor painful at 50 dB (Schriver-Mazzuoli, 2007). In the open plan office, even when employees have perfect self-restraint, noise is inevitable given constant entries and exits, professional discussions and phone calls. In response to the continual stream of noise in the open plan office, some employees attempt to permanently alleviate the discomfort through medical consultation and medication overuse (Muzet, 1999; Thomas, Tomb, Thomas, 2006).

Work Relationships:

Increasingly, employees are gathered in offices and visible to all. This degree of proximity with one another is undesirable among employees. The layout and distribution of employees are considered a strategic resource. For example, the workspace can be optimized by the employer through increasing the number of employees in the office. Alternatively, gathering or separating employees can serve as a strategy on the part of the employer to enhance or reduce communication. Open plan offices can facilitate social relationships between employees. Better relationships increase the level of satisfaction and motivation at work, leading to better performance. Similarly, visibility enables the sharing of business information (Oldham and Brass, 1979). However, opinions differ. Whereas some researchers claim that an open plan office allows more and better work, others (e.g., De Croon, Sluiter, Frings-Dresen and Kuijet, 2005) found no strong correlation between working in an open plan office and employee performance. The proximity allows communication, coordination and cooperation. Employees can listen and share information. The space is no longer used only for work but also for employees to communicate and help one another. Nonetheless, employees, even those who are far from antisocial, may not necessarily want to communicate throughout the day. Yet, the person who does not follow the rule of the group tends to be quickly dismissed. According to Fischer (1964), “the whole structure of interaction between people is marked by the spatial context through which it expresses itself.” The individual obeys rules to be understood, appreciated and integrated into the group.

As shown by De Croon, Sluiter, Frings-Dresen and Kuijet (2005), privacy is completely lacking in the open plan office. There is a strong correlation between working in an open plan office and the lack of privacy. This lack of intimacy becomes a source of stress for the employee and can create a sense of paranoia. In some cases, the visibility imposed by the open plan office results in stress reactions to the constant control (Fischer, 1997).

The open plan office entails the idea of several people working in the same space. These people, who find themselves working together, tend to represent different backgrounds, culture or ethnicity. At this age of globalization, companies need to assess the impact of cultural differences, especially when cultural dynamics play such an important role in determining management practices.

Job-related stress has now become a major challenge for organizations. This type of stress is not only harmful to the employee but has also serious consequences for the company. Negative workplace conditions can become a source of pain that causes psychosocial disorders (Sahler et al., 2007). Today, the employee is gradually losing control of his workspace. Stress, therefore, encompasses the emotional and physical structure of the employee. Working in open space can be perceived negatively by employees, resulting in a loss of identity and intimacy, increased stress, absenteeism, heightened blood pressure and a growth in turnover. Employers should rethink the workspace and return to traditional offices: small, private, closed.

Conclusion

The workspace is a strategic resource that confers a competitive advantage on the company if used properly. As an image of the organization, the workspace determines whether an employee will work according to the expectations of the company.

The work environment is designed as a managerial tool to achieve certain organizational goals. The space is intended to reflect the values and culture of a company that takes the initiative to develop the work environment. Three groups of actors effectively control the spatial configuration of the workspace: designers, administrators and users (Davis, 1984). The company makes decisions concerning the type of space, furniture arrangement, decoration and lighting while maintaining safety standards.

The employee identifies himself with his company through its environment (Joffre and Koenig, 1992). The company may include the employee in the process of developing his personal environment. In this way, the space becomes a strategic tool as the employee feels more involved in company decision-making and experiences improvements in both motivation and the quality of life at work. We can even assume that his need for self-esteem is satisfied.

In recent decades, there have been many changes such as new technologies, new forms of management and the reducing barriers between professional and private life. These changes create new sources of tension and new forms of insecurity that could undermine the involvement of the individual while increasing the likelihood of burnout (El Akremi, Guerrero, Neveu, 2006). Job stress has now become a major risk that organizations must face, with stress-related illnesses being not only harmful to the employee but also posing serious consequences for the company. Poor workplace conditions become a source of pain that can cause psychosocial disorders (Sahler et al., 2007). Job stress is defined in three stages: cause, effect and outcome (Stora, 2008). Today, the employee is gradually losing control of his workspace. Stress, therefore, encompasses the emotional and physical structure of the employee. The Sumer survey, conducted in 2003, shows that noise is the most common cause of stress. In all of the workspaces surveyed, 18% exceeded the threshold of 85 dB, compared with just 14% in 1994 (Stora, 2008). In December 2008, an Australian study investigated the relationship between open space and health. According to researchers, working in open plan offices lowers productivity and increases stress. Dr. Vinesh Oommen, from the University of Queensland, said that the results were a “real shock”. In 90% of cases, working in open space was perceived negatively by employees and appeared to cause a loss of identity and intimacy (De Croon, Sluiter, Frings-Dresen and Kuijet, 2005), increased stress, absenteeism, heightened blood pressure and a growth in turnover. Employers should rethink the workspace and return to traditional offices: small, private, closed.

We cannot deny the benefits of open plan offices, which allow communication, friendliness and, in most cases, better information flow. However, as shown in De Croon, Sluiter, Frings-Dresen and Kuijet (2005), the correlation between the open plan office and performance is low. Further work on the relationship between the workspace, and especially the open plan office, and employees’ productivity is underway. More research on the impact of space-related work conditions on stress is necessary to deepen our insight into the importance of the workspace.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Abou, Hamad J. (2012). ‘Space and Living Conditions at Work: The Case of the Open Plan Office,’ Proceedings of the 18th International Business Information Management Association (Ibima), Isbn: 978-0-9821489-7-6, 9-10 May 2009, Istanbul, Turkey.

Altman, I. (1975). The Environment and Social Behavior: Privacy, Personal Space, Territory, Crowding, Brooks/Cole Publishing Company, Moterey, California.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Amadieu, J.- F. (2005). Le Poids Des Apparences, Beauté, Amour et Gloire, Odile Jacob.

Publisher

Bentham, J. (1977). ‘Le Panoptique,’ Editions Pierre Belfond.

Google Scholar

Chan, J. K., Beckman, S. l. & Lawrence, P. G. (2007). ‘Workplace Design: A New Managerial Imperative,’ California Management Review, 49 (2), 6-22.

Google Scholar

Chenu, A. (1998). ‘Le Bureau, Espace Social, Espace Technique,’ Le Monde du Travail, Editions La Découverte & Syruis, Paris, 112 – 118.

Davis, T. R. V. (1984). “The Influence of the Physical Environment in Offices,” The Academy of Management Review, 9 (2), 271-283.

Publisher – Google Scholar

De Croon, E., Sluiter, J., Kuijer, P. & Frings-Dresen, M. (2005). “The Effect of Office Concepts on Worker Health and Performance: A Systematic Review of Literature,” Ergonomics, 48 (2), 119 – 134.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Durkheim, E. (1930). Le Suicide, Quadrige Puf.

Publisher

El Akremi, A., Guerrero, S. & Neveu, J.- P. (2006). ‘Comportement Organisationnel,’ De Boeck Université, 2, Chap. 11.

Faure, A. (2006). “Quelques Éléments de Réflexion Sur La Notion de Territoire,” Conférence Cap’ Com Au Sénat, Intercommunalité : Une Communication À Réinventer, 4th Of July.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ferris, J. (2007). ‘Then We Came to the End,’ Little Brown.

Google Scholar

Fischer, G.- N. (1964). ‘La Psychologie De L’espace, “Que Sais-Je,’ Presses Universitaires de France.

Fischer, G.- N. (1978). ‘L’espace Comme Nouvelle Lecture du Travail,’ Sociologie du Travail, (4), 397 – 422.

Google Scholar

Fischer, G.- N. (1989). ‘Psychologie des Espaces de Travail,’ Armand Colin.

Google Scholar

Fischer, G. N. (1991). ‘Espace, Identité et Organisation, L’individu Dans L’organisation : Les Dimensions Oubliées, Sous La Direction de Jean-François Chanlat,’ Lava, Presses Universitaires de Laval, Ed. Eska.

Fischer, G.- N. & Vischer, J. C. (1997). L’evaluation des Environnements de Travail, La Méthode Diagnostique, de Boeck Université.

Publisher

Floru, R., Cnockaert, J.- C. & Moncelon, M. (1991). Introduction À La Psychophysiologie du Travail, Presses Universitaires de Nancy.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Giddens, A. (1984). ‘The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration,’ Polity Press Cambridge.

Google Scholar

Goffman, E. (1973). La Mise En Scène de La Vie Quotidienne Tome 2: Les Relations en Public, Les Éditions de Minuit.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Guerrero, S. (1999). ‘Le Besoin de Contrôle de Quoi S’agit-Il?,’ En Quoi Est-Il Utile Aux Gestionnaires? L’exemple des Pratiques de Responsabilisation, Xème Congrès de L’agrh, Actes.

Google Scholar

Hall, E. T. (1966). La Dimension Cachée, Points.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hascher, R., Jeska, S. & Klauck, B. (2002). Office Building: A Design Manual, Birkhäuser.

Publisher

Hayen, A. (1937). “La Théorie du Lieu Naturel D’après Aristote. Contribution À L’étude de L’hylémorphisme,” Revue Néo-Scolastique de Philosophie, 40ème Année, Deuxième Série, (35), 5 – 43.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hediger, H. & Vincent, É (1995). ‘Psychologie des Animaux Au Zoo et Au Cirque,’ Traduit de L’allement Par Edith Vincent, René Julliard, Paris.

Google Scholar

Howard, E. (1920). ‘Territory in Bird Life,’ Murray, London.

Google Scholar

Joffre, P. & Koenig, G. (1992). ‘Gestion Stratégique : L’entreprise, Ses Partenaires-Adversaires et Leurs Univers,’ Éditions Litec, Collection Les Essentiels de La Gestion

Google Scholar

Lefebvre, H. (1974). La Production de L’espace, Anthropos.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lemoine, J. F. (2003). “Vers Une Approche Globale de L’atmosphère du Point de Vente,” Revue Française du Marketing, 4 – 5(194), 83 – 101.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Linkemer, B. (1999). Polish Your People Skills, Amacom New Media, Chap. 3.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Maclouf, E. (2005). ‘Les Espaces de Travail: Place et Rôle Dans La Gestion des Organisations,’ Thèse En Sciences de Gestion, Sous La Direction du Professeur Frédéric Wacheux, Université Paris 1 Panthéon – Sorbonne.

Google Scholar

Martinache, I. (2011). “Comment S’exerce Le Contrôle Social?,” Alternatives Economiques, (299), Février.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and Personality, Second Edition 1970, Harper & Row, New York.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Muzet, A. (1999). ‘Le Bruit,’ Flammarion.

Newsham, G. R. (2003). “Making the Open-Plan Office a Better Place to Work,” Construction Technology Update, Dec. (60).

Publisher – Google Scholar

Oldham, G.- R. & Brass, D.- J. (1979). “Employee Reactions to an Open-Plan Office: A Naturally Occurring Quasi-Experiment,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Jun., 24 (2), 267 – 284.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Oommen, V. G., Knowles, M. & Zhao, I. (2008). “Should Health Service Managers Embrace Open Plan Work Environments?,” Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 3 (2), 37-43.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Pelegrin-Genel, E. (2006). 25 Espaces de Bureaux, Amc Le Moniteur.

Publisher

Sahler, B., Bethet, M., Douillet, P. & Mary-Cheray, I. (2007). Prévenir Le Stress et Les Risques Psychosociaux Au Travail, Editions Anact.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Schriver-Mazzuoli, L. (2007). ‘Nuisances Sonores,’ Dunod.

Sommer, R. (1969). Personal Space: The Behavioral Basis of Design, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Stora, J. B. (2008). ‘Le Stress, Collection “Que Sais-Je ?,’ Presses Universitaires de France.

Sperandio, J. C. (1980). ‘La Psychologie En Ergonomie,’ Presses Universitaires de France.

Google Scholar

Taskin, L. & Vendramin, P. (2004). Le Télétravail, Une Vague Silencieuse, Louvain-La-Neuve, Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

Publisher

Thomas, J., Tomb, E. & Thomas, E. (2006). La Migraine, La Comprendre et La Guérir Définitivement, Heures de France.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Veitch, J. A., Newsham, G. R., Boyce, P. R. & Jones, C. C. (2007). “Office Lighting Appraisal, Performance and Well-Being: A Linked Mechanisms Map,” Proceedings of the Cie, 26th Session, 4 July – 11 July 2007, 1, Beijing, China, D3-61 – D3-64.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Wacheux, F. (1997). ‘La Gestion des Ressources Humaines et L’épistémologie Du Quotidien,’ Les Cahiers Du Cergors.

Google Scholar

Zarama, G. & Vinck, D. (2011). “Façonnage des Espaces de Travail D’un Collectif de Recherche En Micro et Nanotechnologies,” Terrains & Travaux, 1 (18), 61-80.

Publisher – Google Scholar