Introduction

Outsourcing is the assignment of core services or operations of the organization to a provider that focuses in that area of service or operation (Carr and Nanni 2009). One top reason hospital executives choose to outsource support services is to reduce operating costs (Sunseri 1999). This speculative desire only works if the outsourced service delivers on stated promises. According to Sunseri (1999), most respondents were satisfied with the results of their outsourcing vendors. Hospital leaders who retain the services in-house often based their decision on the belief that their present staff can perform the duties as well or better than an outside vendor can (Sunseri 1999). Large service companies, such as Sodexo and Aramark, provide outsourcing services in the areas such as facilities management, housekeeping, food services, and Bio-Med (Sanders 2004). These larger organizations can leverage business volume to secure lower pricing.

Outsourcing — Why Would You?

Obtaining the required positive and measurable benefits to convince the hospital’s senior leadership to embark on the journey of outsourcing is daunting. According to Hazelwood et al. (2005) outsourcing of services offers remunerations to healthcare facilities. In the example of a successful outsourcing venture, as demonstrated by Hazelwood et al. (2005), the hospital received measurable benefits from the services provided from India in the area of reading radiological results to be transcribed in patient’s charts. Reading the opening salvo of this article, a senior leader could easily become excited about the concept of outsourcing (Hazelwood et al. 2005). What other non-core services may be available to the senior leaders and how will the outsourcing influence the hospital’s bottom line? These are questions worth asking to keep hospitals operating efficiently while maintaining a high level of patient care and satisfaction.

Outsourcing vendors strive to provide the non-core services that allows the hospital to focus on the business of serving patients (Sanders 2004). As an industry, the business of administrating hospitals has become very complex. Reimbursements from federal and state agencies have become difficult to manage and track. Regulatory requirements have become more complex. Patient expectations are becoming greater each year. According to Otani et al. (2005), patient satisfaction is subjective when evaluating care provided, but the judgment is the driver when patients have a wide selection of health care providers. “Thus, it is very important to improve patient satisfaction levels, especially in today’s competitive healthcare environment in which managed care companies use patient satisfaction as a tool in determining their reimbursement rates” (Otani et al. 2005, p. 311).

Consequently, if a hospital can shed some of the managerial responsibilities for some of the functions that support the healing environment they can focus more intently on the core medical necessities. Sodexo and Aramark are such companies that have refined their outsourcing services for hospitals. In the food service business, outsourcing vendors can provide the food preparation and serving to patients, visitors, and staff. Innovative ideas, such as room service style dining, provide an opportunity for the patients to order a meal at their convenience. An environmental service provides the cleaning of all patient, staff, and visitor areas. Within the facilities management purview, the important management of engineering repairs, preventative maintenance, utility consumption, and emergency response to equipment failure are but a few of the specific engineering services provided (Sodexo 2013). A full laundry service can provide these services at the hospital facility or the laundry services can process and return laundry within one day (Sodexo 2013). In some instances, two or more hospitals might collaborate on a joint laundry service to obtain better value than if each attempted to go it alone.

The above examples are not the only services provided by outsourcing vendors; they show the depth of potential outsourcing avenues available to any hospital. These services provide an important backbone to the operation of a hospital. In addition, these services can have a direct impact on a patient’s hospital experience and can strongly influence the number of successful healing outcomes. This is because the food, environment, and facilities in a hospital define the nutrition, cleanliness, and comfort of a patient. These three environmental influences are synergistic with patient healing.

The importance as one considers the possibility of outsourcing responsibilities is to contemplate if a competitive marketfor the use of outsourced services exists (Young, 2002). A company that provides these services can often capitalize on acquiring services at multiple hospitals in a region. The buying power of volume purchases and incentives can provide a strong marketing advantage against both independent hospitals and competitors in the marketplace. Many hospitals currently operate several in-house services. Most service providers recognize that targeting these potential accounts would be more fruitful than taking over an account that currently is with a competitor (Young 2002). This is because many hospitals are rebidding their outsourcing services and looking to obtain a lower cost outsourcing contract. The competitive nature of this type of activity drives down the potential profit for the outsourcing vendor. Young (2002) also stresses the importance of this knowledge as one considers the specialized services required by the hospital.

Nowhere is this more true than in the operation of facility engineering. Engineering management requires an understanding of mechanical and electrical machinery. It is important to understand how to perform maintenance on the machinery, functions, and optimization for efficient operation and resulting lower operating costs. It is critically important to have trained and properly qualified operators on staff to maintain and operate the machinery (Young 2002). This operating staff must have a strong backup staff that understands the value of preventive maintenance, energy consumption, and the benefits of potential plant upgrades or new construction. With a through and proper understanding of equipment operation and appropriate modifications for improvement, an engineering department can realize savings that benefits the hospital. Achievement of this is only when the properly trained and highly talented staff are available or accessible to the organization.

Young (2002) concentrated on maintenance; however, a direct link exists through all types of outsourcing. Upon considering the possibility of outsourcing a task, Young (2002) offers a six-step process for consideration. Modification of these steps is encouraged, as necessary, to fit the particular needs of the facility. In deciding which of these steps to consider, the senior decision maker must carefully consider the verification process to be used. To ensure the desired results and reduce financial costs, there must remain in place a secure method to hold the contractor to an agreed upon standard of excellence (Alfonsi 2013, Sullivan 2009).

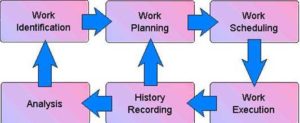

Fig 1. Task Development and Evaluation Process (Dunn 2009)

Identification of the tasks is very important in understanding how the hospital best can use the services of the outsourcing company. The task identification process must occur prior to the request for a bidding document as the hospital identifies its own needs and includes this in a Request for Proposal (Alfonsi 2013). The more detailed identification of work occurs once an outsourcing company performs an initial site survey (Osmond and Schnaper 2000) These results or findings drive work planning and work scheduling. The plan can execute in accordance with a well-developed strategy. Recording and analyzing the execution is part of a thorough, professional outsourcing company’s processes. At any point in the cycle, the recording and analysis steps can update the original work identification and work planning (Dunn 2009). These necessary feedback loops keep the operation efficient and successful.

Senior executives must remain aware that the outsourcing company’s motivation to complete the service is profit. This in itself is acceptable as long as the profit made, balances with the work provided, and the quality of services provided remains acceptable to healthcare standards and laws. As healthcare services integrate with technology, the ability to convert longstanding traditional practices with newer and faster digital ones requires careful evaluation of outsourcing needs (Sen et al. 2010). Taking the necessary time to check references and meet with senior leaders of other hospitals will provide dividends in the hospital receiving value for the dollar paid to the service provider. Outsourcing, in other words, is a two-way street requiring respect and understanding between the two parties. This respect and understanding will provide a win-win for both organizations and potentially provide a future partnership in other healthcare opportunities that may include core medical services that directly involve patient care (Roberts 2001).

Obstacles to Outsourcing

Obstacles of outsourcing can be many or just a few. Customers of outsourcing will face barriers, either the company doing the outsourcing or company doing the job. There are several barriers to evaluate, such as the cost of hiring someone else to do the job and if it makes financial sense (Barthélemy and Adsit 2003). Can the hospital justify the cost not to keep the service in-house? Does the outsourcing vendor have the required experience to make outsourcing cost-effective for the hospital? Affected managers are another challenge of outsourcing. When hiring the outsourcing vendor, hospital management may attempt to blame the outsourcing vendor if the project does not meet the hospital’s financial goals (Barthélemy and Adsit 2003). If the project reaches that point, the outsourcing vendor may say that the hospital made an error in the statement of work. This regrettably can be the beginning of “the blame game” or lose-lose situation for all parties.

When hospitals start down the outsourcing road, they perceive to encounter three to four barriers. In today’s society, businesses have gotten away from maintaining loyalty to organizations and people. Employees change employers frequently, increasing turnover rates. There is still the question of when a hospital is looking to outsource, that organizational values may favor in-house employees over outsourced employees. In hospitals, value of the person who is filling the position is a major barrier (PwC 2013). In addition, hospital leaders need to ensure they possess the required skills to manage outsourcing, to maintain control and consistency in the workplace that outsourcing may disrupt. Managers have to realize that there may be a patient, as well as an employee reaction to outsourcing, that if not managed properly, it will be a barrier to operations (Foxx et al. 2009). If the organization has interest in a vendor proficient in the area they are looking to outsource to, a complete statement of work will save time and money in the transition. Managers do not to have outside providers telling them that they have a payroll problem that will cost them more to fix than the original outsource contract.

According to Wong (2006) there are several key aspects of outsourcing and the following five are considered the most significant.

- Many outsourcing agreements suffer “suicide by change order.”

- What senior leadership does not understand will harm the organization.

- Outsourcing vendors build in vagueness — the “black box” of unexpected costs.

- Outsourcing firms are starting to over stretch themselves.

- Many customers want a flexible and innovative partner but do not get it.

Outsourcing is estimated to be a multi-trillion dollar business (Hazelwood et al. 2005). However, is it a good business plan or is it just a moneymaking system? Has the organization outsourced employment by not keeping the jobs in-sourced (Hazelwood et al. 2005)? Single function outsourcing can be less challenging and cost less. If you outsource collections and billing functions for example, it can be saving the facility money. When outsourcing a department or service, leaders will find many management and cost issues that may make it less cost effective (Kakabadse and Kakabadse 2003). This issue alone can give management a difficult time on what service functions to keep in-house and what is outsourced.

When contemplating an option to outsource (a single or multiple) services, the health care facility must consider its tax status (Hazelwood et al. 2005). There are three predominant categories. One is a for-profit facility where the goal is to make money for owners or shareholders. A second category is not-for-profit. In this case, a facility might be allowed to make a profit in certain areas but the overall objective of the organization at the end of the fiscal year is to be revenue neutral (Hazelwood et al. 2005). Finally, there is the nonprofit organization. This type of facility is typically owned and operated by the community or a religious organization wherein their mission is to provide a community health care service that is not based on a profit motive (Hazelwood et al. 2005, Michael 2004). Much of their services are focused on low income and indigent individuals and often located in rural towns or older and lower economic areas of the community.

The next obstacle in outsourcing is people. When a hospital outsources and terminates staff to transition to the outsourcing vendor there will be an impact on morale within the organization (Barthélemy and Adsit 2003, Elfenbein 2007). The remaining employees, who after outsourcing, may not be supportive of the change to the hospital’s new status quo. When outsourcing occurs, employees are often not very happy with the management and lose their trust in management. A question is raised concerning the qualifications of the outsourced employees (Hazelwood et al. 2005). If the outsourcing vendor hired inferior staff, then is the hospital getting the value has been promised? Management’s task of supervising employees will increase in this situation. Can management trust the remaining employees to keep performing at a high-level when they are not sure how long they have employment?

The outsourcing concept can cause a control and dependence issue for the management at the facility (Sullivan 2009). Managers who get outsourcing contracts may find that getting out of the contracts can be a financial risk and cause serious service disruption. Typical outsourcing contracts are long-term, usually five to seven years in length (Churchill 2008). The length of a contract in today’s society is an important consideration for hospital administration. Hospitals have a fast-changing world and a long-term contract might not be a good investment.

Managing obstacles is the guiding method used to manage outsourcing contracts. The contract may have inadequate requirements that both managers and outsourcing vendors do not fully understand. Hospital contract managers who do not understand or fully appreciate the contract terms may be paying for services that are not being performed (Saidel and Harlan 1998). The same may apply for the outsourcing vendor, for services they have provided but are not being reimbursed. There are significant risks for all participants when poorly written contracts are executed and when managers do not fully know what the contract includes (Sullivan 2009).

Best Practices

Best practices are a set of guidelines, ethics, or ideas set forth by required authority that represent the most efficient or prudent course of action (Alfonsi 2013, Churchill 2008). Outsourcing involves the delegation of services and operations to others who have the expertise to perform the services more efficiently, cost effectively, and yet maintain the required accepted standard (Alper 2004, Anonymous 2005). According to Barthélemy and Adsit (2003), in the United States and Europe, there are seven deadly sins of outsourcing and they include:

- Outsourcing services that should stay within the organization.

- Selecting the incorrect outsourcing vendor for the job.

- Writing a poor statement of work for the outsourcing service.

- Disregarding employee concerns about outsourcing.

- Permitting the outsourced service get out of control.

- Neglecting to realize the full costs of outsourcing.

- Failing to strategize an exit procedure before terminating the outsourcing contract.

Outsourcing programs involve five basic obstacles that face nearly every organization planning to outsource some of its in-house services. Finding and selecting the right vendor largely depends on the organizational size, culture, and values. The major pitfalls on the path of successful outsourcing include (a) poor request for proposal design, (b) possible pressures from internal constituents, (c) changing priorities, (d) unrealistic expectations, and (e) bad decision-making (Osmond and Schnaper 2000).

Many experts agree that while healthcare systems vary widely across the globe, three things are common to all: cost, quality, and access (Chan 2008). In addition, there is evidence that a growing and lingering global recession has direct fiscal relationship with quality of healthcare delivery (Chan 2008). Further, there is an aging population forcing hospitals to take steps to sort out what changes are necessary to their operations. A graphic example is the nearly 40 million uninsured individuals within the United States. These three areas of cost, access, and quality make it imperative for the healthcare services providers to consider outsourcing as a viable alternative to address the growing challenges (Chan 2008).

The outsourcing advocates argue that outsourcing of healthcare support services represents a viable strategy for meeting the challenges of improving healthcare delivery (Aramark Healthcare 2011b, Sullivan 2009). A study noted that of the 64 highly successful outsourcing relationships only 66% of the customers ranked creating a structure for collaboration as a key factor in their efforts (Alfonsi 2013).

The health care industry is an example of the growing need for outsourcing. Health care spending in the United States continue to increase at a rapid rate exceeding $1.5 trillion, or an average of $5,500 per person (Churchill 2008). The fluctuating demographics of the United States populace continue to hasten health care spending increases. Churchill (2008) estimated that by fiscal year 2011, health care expenditure will surpass 20% of the United States Gross National Product. Health insurance companies and government agencies face a recurrent decline in their operating budgets and rising costs for their service programs. The United States shortfalls exceed $70 billion for healthcare services (Churchill 2008). These expected shortfalls will increase in the future until a new plan becomes known. The growing need of healthcare outsourcing is largely because of the rapidly increasing cost of health care services. The cost of government medical programs has shifted to health care providers. This leads to health care providers receiving less compensation for their services and they face increased burdens from patients to continue to provide superior care (Churchill 2008). In reaction to this, health care service providers are seeking outsourcing solutions to fight these growing costs.

Defining outsourcing best practices for components of healthcare services is difficult. As outsourcing grows in the health care industry, the size and complexity of outsourcing contracts grow at an equal pace (McGee 2012). Developing practices for outsourcing can vary in intricacy. Practices may include outsourcing with a one-time contract with a specialized vendor, some complex outsourcing involves multiple contracts with multiple vendors, and shared service practices in which the organization and outsourcing vendor collaborate in certain functional tasks (Sullivan 2009). An important component in achieving a successful outsourcing relationship is adopting a shared service model or one-time service contract model or require vendors to negotiate the full scope and involvedness of outsourcing. This action will assist in reaching an effective contracting decision with mutual benefit for both parties. Contract agreement specifics are best effective when both parties (e.g., hospital and outsourcing vendor) are working together to define them. Some areas to think about are: how sensitive data handled, how agreement modifications are accomplished, and how to resolve conflicts that may arise.

Successful outcome of outsourcing largely depends on transparency, integrity, and trust. The complexity of outsourcing issues requires sufficient time to call for vendor applications, to study the proposals, and selecting vendors to interview. Where there are no experts within the organization, invite outside consultants to manage the vendor selection process. There is no doubt that outsourcing of support services in healthcare allows an organization to realize substantial strategic advantages. These include among others, improved patient services, restored employee retention rates, superior access to resources, increased cost savings, cost prevention, hazard mitigation, and access to money for improvements (Aramark Healthcare 2011a).

Ensuring quality healthcare delivery is the central concern for any health care delivery system. There is a growing consciousness about the utility of outsourcing of services, especially as it relates to health care industries. To undertake the task of outsourcing support services, senior leaders should ask the tough questions that would guide their understanding of issues relating to outsourcing.

Implications to Hospital Management

Outsourcing is a process that can take the burden off corporations in terms of fixed and variable costs. In addition to reducing costs, replacing services that have underperformed within the organization can increase the corporate image of the organization. Healthcare organizations are no exception to these phenomena. Off-limit or out of reach hospital services are no longer an issue to outsourcing providers (Michael 2004). There are many benefits to outsourcing services within a hospital setting. An immediate benefit to outsourcing is the reduction in expenses for the outsourced services in regard to staffing and training (Buxbaum 2011). An additional benefit is that quality of the services provided increase and may result in increased customer satisfaction. However, senior decision makers must ensure that the outsourced services are being, and continue to be, performed by qualified individuals regardless of the service they are providing (Hazelwood et al. 2005).

Although there are many positive aspects of outsourcing that seem very enticing to hospital senior leadership, there are just as many potentially negative aspects. There are legal, ethical, and perhaps moral issues to think of when considering outsourcing. Legal issues are very complex and diverse, but some issues are important to understand when entering into an outsourcing contract (Hazelwood et al. 2005). If the outsourcing vender’s employee fails in a core competency, which results in injury to a patient or an infraction of the Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act of 1996 or Privacy Act of 1974, who is liable? The hospital, the outsourcing vendor, the individual employee, or is it all the above? There can be several answers to this question and it is a possibility that this may happen to a hospital organization in the normal operations of business.

Understanding the legal aspects that arise from outsourcing services is essential (Hazelwood et al. 2005). Only a qualified lawyer can definitively answer questions concerning legal aspects. However, it is well worth the investment of having a lawyer review all documents relating to the outsourcing process to ensure there are no surprises. Ethical issues can also arise from outsourcing. Is there an ethical responsibility to inform the patient whom his or her lab work or other service is provided by a contracted or outsourced third party? This issue may have to go before the legal department for a decision, but it is a commonly overlooked aspect in many organizations (Hazelwood et al. 2005).

Moral issues are often challenging to resolve. How problematic will it be to terminate all the employees from a department because the hospital leadership has decided to outsource their jobs? Will the hospital offer severance pay or package to the outsourced employees? Will the outsourcing vendor rehire the employees? These are the more human-side of business and often more difficult to remedy.

Many hospital organizations are outsourcing services and seeing a near immediate return on their investment decision. For example, training an individual in medical transcription is a costly and timely process (Kshetri and Dholakia 2011). Ensuring that they can understand a provider’s verbal notes and record the conditions correctly the first time is critical for the continued care of the patient. Outsourcing this service has shown to affect the bottom line (Kshetri and Dholakia 2011). This is also true for billing/collections and teleimaging services within a hospital (Kshetri 2009). Unlimited opportunities for outsourcing are often readily identifiable in a hospital organization. There have been hospitals that have outsourced their executive staff (Burkholder 2006, Hazelwood et al. 2005). However, outsourcing of hospital executive staff is an uncommon occurrence (Burkholder 2006, Hazelwood et al. 2005).

Does the organization have a qualified individual who monitors the contracted outsource vendor’s contract performance? Is there a process to remedy the issue of non-performance or under-performance? These overlooked aspects arise routinely when outsourcing (Roberts 2001). Many organizations see outsourcing as a “set it and forget it” action taken by the organization’s senior leadership (Kshetri and Dholakia 2011). Although this can be true, it is often not the case because of the outsourcing vendor’s management style and management processes. Of course, the organization will see a dramatic change when the outsourcing vendor takes over but maintaining the level of performance is often difficult. Having adequate contract performance monitors or assessment routine could decrease the occurrence of performance drift (Foxx et al. 2009).

There are other common areas generally not outsourced. Areas not commonly outsourced are the core services. Health care providers such as surgeons, physicians, and nursing staff are often organizational employees because the hospital can have greater control over these individuals and the services that they provide. Another area generally not outsourced is the human resources department (Roberts 2001). Many organizations like to keep control of those working directly for the organization and therefore rarely are human resource departments outsourced (Roberts 2001). Looking at the dramatic opposite, there are hospitals that outsource everything from the support staff to the facility itself. While there is a large range of options when considering outsourcing, it is the responsibility of each organization to determine if outsourcing is good for them. If it the organization decides to outsource, careful evaluation is essential to ensure that the actions taken will help meet the organization’s mission, vision, and goals.

Outsourcing is the assignment of core services or operations of the organization to a provider that focuses in that area of service or operation (Carr and Nanni 2009). One of the top reason hospital executives choose to outsource services is to reduce operating costs while increasing quality of services to the patient (Sunseri 1999). This speculative desire only works if the outsourced service delivers on stated promises. According to Sunseri (1999), most respondents were satisfied with the results of their outsourcing vendors and all hospitals that use outsourcing desire that outcome. Those hospital leaders who retain the services in-house based their decision on the belief that their present staff can and will continue to perform the duties as well or possibly better than an outside vender can. Large outsourcing companies, such as Sodexo and Aramark, provide outsourcing services in the areas that hospitals need (Sanders 2004).

The bottom line to outsourcing is that there is no silver bullet and no such thing as one-size-fits-all. However, with a careful, thoughtful, and deliberate approach, outsourcing can be successfully implemented in a manner that benefits administration, staff, the vendor, and most importantly, the patient.

Acknowledgements

Kelley A. Conrad, Ph.D. (University of Phoenix – School of Advanced Studies) for his guidance and direction during the development of this work. Mr. Paul Canady, Captain, USN (Ret), for his succinct comments and suggestions.

References

Alfonsi, M. J. (2013). “Twelve Best Practices to Create a World Class Outsourcing Case,” [Online], Available:http://www.outsourcing-center.com/2013-01-twelve-best-practices-to-create-a-world-class-outsourcing-case-article-

53821.html [accessed January 14, 2013].

Publisher

Alper, M. (2004). ‘New Trends in Healthcare Outsourcing,’ Employee Benefit Plan Review, 58(8), 14-16.

Google Scholar

Anonymous (2005). ‘Outsourcing Trends to Watch in ’05,’ Fortune, 151(6), C1.

Google Scholar

Aramark Healthcare (2011a). “Delivering Value: Healthcare Non-Clinical Outsourcing,” Position Papers [Online], Available: http://www.aramarkhealthcare.com/RelatedFiles/Outsourcing_position_paper_1105.pdf [accessed Janauary 13, 2013].

Publisher

Aramark Healthcare (2011b). “Global Strategies for Outsourcing Support Services,” Position Papers [Online], Available:http://www.aramarkhealthcare.com/DownloadFile.aspx?PostingID=1009&ChannelID=491 [accessed January 14, 2013].

Publisher

Barthélemy, J. & Adsit, D. (2003). “The Seven Deadly Sins of Outsourcing [And Executive Commentary],” The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005), 17(2), 87-100.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Burkholder, N. C. (2006). Outsourcing: The Definitive View, Applications, and Implications, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Buxbaum, J. L. (2011). “Spotlight on HIEs and EHRs. How Outsourcing Fits in,” Health Management Technology, 32(5), 20-21.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Carr, L. P. & Nanni, A. J. (2009). Delivering Results: Managing What Matters, New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Chan, M. (2008). ‘Globalization and Health,’ Translated By New York, NY: United Nations.

Churchill, C. J. (2008). “Outsourcing Contracts: Trends and Best Practices,” [Online], Available:http://www.barley.com/publications/article.cfm?Article_ID=244 [accessed Janaury 13, 2013].

Publisher

Dunn, S. (2009). “Maintenance Outsourcing – Critical Issues,” [Online], Available: http://www.plant-maintenance.com/outsourcing_crit_issues.shtml [accessed January 13, 2012].

Publisher

Elfenbein, H. A. (2007). “Emotion in Organizations: A Review and Theoretical Integration,” Academy of Management Annals, 1, 315-386.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Foxx, W. K., Bunn, M. D. & McCay, V. (2009). “Outsourcing Services in the Healthcare Sector,” Journal of Medical Marketing, 9(1), 41-55.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hazelwood, S. E., Hazelwood, A. C. & Cook, E. D. (2005). “Possibilities and Pitfalls of Outsourcing,” Healthcare Financial Management, 59(10), 44-48.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kakabadse, A. & Kakabadse, N. (2003). “Outsourcing Best Practice: Transformational and Transactional Considerations,” Knowledge and Process Management, 10(1), 60-71.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kshetri, N. (2009). ‘Developing Economies’ Shift from Supplying Low- To High-Value Added IT-Enabled Services: A Case Study of the Indian Healthcare Offshoring Industry,’ In Southern Management Association (SMA) Conference, Asheville, NC, 11-14 November 2009, Southern Management Association, 48-53.

Kshetri, N. & Dholakia, N. (2011). “Offshoring of Healthcare Services: The Case of US-India Trade in Medical Transcription Services,” Journal of Health Organization and Management, 25(1), 94-107.

Publisher – Google Scholar

McGee, J. (2012). “Outsourcing and Contract Services,” Journal of Biomolecular Screening, 17(10), 1379-1381.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Osmond, T. A. & Schnaper, B. M. (2000). “Tips, Traps, and Travails: How to Hire the Right Outsourcing Vendor for Your Organization,” Benefits Quarterly, 16(3), 15.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Otani, K., Kurz, R. S., Harris, L. E. & Byrne, F. D. (2005). “Managing Primary Care Using Patient Satisfaction Measures/Practitioner Application,” Journal of Healthcare Management, 50(5), 311-325.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Pwc (2013). “Shared Services and Outsourcing,” [Online], Available: http://www.pwc.com/sourcing [accessed January 13, 2013].

Publisher

Roberts, V. (2001). “Managing Strategic Outsourcing in the Healthcare Industry,” Journal of Healthcare Management,46(4), 239.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Romano, M. (2004). “Outsourcing Everything. Accelerating Use of Outsourcing Adds to Public Policy Debate While Raising Questions about Hospitals’ ‘Charitable’ Status,” Modern Healthcare, 34(14), 24-26.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Saidel, J. R. & Harlan, S. L. (1998). “Contracting and Patterns of Nonprofit Governance,” Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 8(3), 243.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Sanders, S. (2004). ‘Outsourcing,’ Sanitary Maintenance, 62(5), 12.

Sen, S., Raghu, T. S. & Vinze, A. (2010). “Demand Information Sharing in Heterogeneous IT Services Environments,”Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(4), 287-316.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Sodexo (2013). ‘Hospitals,’ [Online], Available: http://www.sodexousa.com/usen/environments/hospitals/Hospitals.asp [accessed January 13, 2013].

Sullivan, J. (2009). Best Practice in Governing Outsourcing Contracts: Establishing and Managing a Center of Excellence, Houston, TX: Equaterra.

Publisher

Sunseri, R. (1999). “Outsourcing on the Outs,” Hospitals & Health Networks, 73(10), 46-2.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Wong, K. (2006). “Top 10 Challenges to Outsourcing,” [Online], Available:http://www.cadalyst.com/management/news/top-10-challenges-outsourcing-6845 [accessed January 13, 2013].

Publisher

Young, S. (2002). “Outsourcing and Downsizing: Processes of Workplace Change in Public Health,” The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 13(2), 244-269.

Publisher – Google Scholar