Introduction

Customer satisfaction is an important facet for service organizations and specifically, it is highly related to service quality. Such development is highly related to the intensity of rivalries of today’s business environment (Lee, & Hwan, 2005). More and more organizations emphasize on service quality due to its strategic role in enhancing competitiveness especially in the context of attracting new customers and enhancing relationship with existing customers (Ugboma, Ogwude, & Nadi, 2007).

Service quality is one of the most important research topics for the past few decades (Gallifa & Batalle, 2010). Consumers are not only concerned with how a service is being delivered but most importantly with the quality of output they receive. Positive perception on quality of services being delivered occurs when it exceeded customers’ expectations. In the context of ensuring sustainability of higher learning, institutions require them to continuously strive towards meeting and exceeding students’ expectations (Anderson, Fornell, & Lehmann, 1994). The main purpose of this research is to examine the relationship between service quality and students’ satisfaction at higher educational institutions in Malaysia.

Literature Review

The services literature focuses on perceived quality, which results from the comparison of customer service expectations versus perceptions of actual performance (Zeithaml, 2000). Customers are likely to be satisfied when their perception on services provided exceeds their expectations. Service quality in educational industry is defined on the basis of students overall evaluation on the services they received which is part of their educational experience. This covers a variety of educational activities both inside and outside the classroom such as classroom based activities, faculty member/student interactions, educational facilities, and contacts with the staff of the institution.

Service Quality

The service quality in the field of education and higher learning particularly is not only essential and important, but it is also an important parameter of educational excellence. It has been found that positive perceptions of service quality has a significant influence on student satisfaction and thus satisfied student would attract more students through word-of-mouth communications (Alves & Raposo, 2010). The students can be motivated or inspired from both academic performance as well as the administrative efficiency of their institution. Ahmed & Nawaz (2010) mentioned that service quality is a key performance measure in educational excellence and is a main strategic variable for universities to create a strong perception in consumer’s mind.

Most of the well-established high learning institutions focus highly on strategic issues like providing excellent customer services. It is important because by doing so they would be able to make and build good relationships with clients which is actually very important in determining their future in the industry (Malik, Danish, & Usman, 2010). Higher learning institutions are like other service based firms which is dependent on people/students perception and one of the easiest yet powerful marketing strategy is through positive word of mouth. One of the most established service quality satisfaction analysis tool is the one developed by Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1988), which they had identified 10 dimensions of service quality; tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, competency, courtesy, communication, credibility, security, access, and understanding.

Moreover, performance measurement of service quality at higher learning institutions is strongly embedded to the matching between students’ expectation and their experience of a particular service (Tahar, 2008). Generally, students evaluate and judge the service quality to be satisfactory by comparing what they want or expect against what they are really getting. Gruber, Voss, & Glaser-Zikuda (2010) believe that the behaviors and attitudes of customer contact employees primarily determine the customers’ perceptions of the service quality provided. This means, human interaction element is essential to determine whether students consider service delivered satisfactory or not. Apart from that, higher learning institutions need to have appropriate infrastructure too such as admin and academic buildings, residential halls, catering facilities, sports facilities, and recreations centre (Sapri, Kaka, & Finch, 2009).

Tahar (2008) discovered that the perception on service quality of higher learning between two nations; the USA and New Zealand varies from New Zealand, as students define quality on the following ranking; ability to create career opportunities, issues of the program, cost/time, physical aspects, location and others. Meanwhile in the USA, they ranked academic reputation as first and later followed by cost/time, program issues, others, physical aspects and choice influences.

Ilias, Hasan, Rahman & Yasoa (2008) identified that the main factors that could affect the level of students’ satisfaction were; students’ perception on learning and teaching, support facilities for teaching and learning such as (libraries, computer and lab facilities), learning environment (rooms of lectures, laboratories, social space and university buildings), support facilities (health facilities, refectories, student accommodation, student services) and external aspects of being a student (such as finance, transportation). With all these capabilities, an institution will be able to meet student expectations and compete competitively.

Student Satisfaction

Kotler and Clarke (1987) define satisfaction as a state felt by a person who has experienced performance or an outcome that fulfill his or her expectation. Satisfaction is a function of relative level of expectations and it perceives performance. Satisfaction is also perceived as the intentional performance which results in one’s contentment (Malik & Usman, 2010). According to Sapri and Finch (2009), customers are the lifeblood of any organization, whether private or public enterprise sectors. Student satisfaction plays an important role in determining accuracy and authenticity of the system being used. The expectation of the students may go as far as before they even enter and engage in the higher education (Palacio, Meneses, & Perez, 2002).

In contrary, Hasan & Ilias (2008) assumed that satisfaction actually includes issues of perception and experiences of students during the college years. Student satisfaction is being shaped continually by repeated experiences in life on campus. The results of previous research reveal that students who are satisfied may attract new students by engaging in speech of positive word-of-mouth communication to inform their friends and acquaintances, and they could go back to the university to further continue their study or take other courses (Helgesen & Nesset, 2007; Gruber et al., 2010).

Students are likely to be satisfied in their educational institution when the service provided fits their expectations, or they will be very satisfied when the service is beyond their expectations, or completely satisfied when they receive more than they expect. On the contrary, students are dissatisfied with the educational institution when the service is less than their expectations, and when the gap between perceived and expected service quality is high, they tend to communicate the negative aspects (Petruzzellis, Uggento, & Romanazzi, 2006).

Tian and Wang (2010) argued that satisfaction is the function of the congruency between perceived performance and esteemed benefits resulting from consumer personal values, and the configuration of consumer values is affected by central cultural values. Moreover, they mentioned that cultural differences have a direct influence on the level of students’ satisfaction regarding their perception of the services, and to satisfy the customers with the same cultural background is not that easy, then to satisfy the customers with different cultural background will be even more difficult. However, Navarro et al. (2005) mentioned that students evaluate the quality of organization on the basis of tangibility (teachers), reliability and responsiveness (methods of teaching) and management of the institution and these factors have direct influence on the level of students’ satisfaction.

According to Mavondo and Zaman (2000), academic reputation of the institution, quality of lecturers and the provision of facilities are important while market orientation is found to be a crucial precedent for student satisfaction. The results of this study indicate that satisfied students provide positive word of mouth and recommend prospective students to the institution at which they are studied.

Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction

Parasuraman, Zeithmal, and Berry (1994) agreed that service quality is one of the basics of customer satisfaction. In addressing the relationship between service quality and satisfaction, they studied a model developed by Oliver (1993). Oliver’s model combines the two concepts and proposes that perceived service quality is antecedent to satisfaction. The outcomes showed that service quality leads to satisfaction. Parasuraman et al., (1988) compared service quality with satisfaction. They defined service quality as a form of attitude, a long-run overall evaluation, while satisfaction as a transaction-specific measure. Based on such definition, it is considered that perceived service quality is a global measure, and so, the direction of causality was from satisfaction to service quality (Parasuraman et al., 1988).

Parasuraman, Zeithmal and Berry (1991) assumed that reliability was basically related to the outcome of service while tangibles, assurance, responsiveness, and empathy were concerned with the process of service delivery. The results not only judge the reliability and accuracy (i.e. dependability) of the service, but they also determine the other service dimensions that are being provided (Parasuraman et al, 1991). Therefore, customer satisfaction can be dependent not only on the rule of customer about the reliability of the service provided but also on the experience of customer with the service delivery process.

Research Methodology

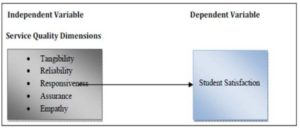

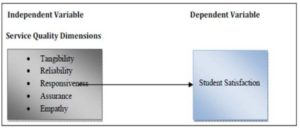

This study adopted Parasuraman’s SERVQUAL dimensions. The dependent variable in this study is the overall student satisfaction over higher learning institutions in Malaysia. The dimensions for the independent variable were tangibility, assurance, responsiveness, reliability, and empathy as illustrated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1: Research Framework

Hypotheses

This study investigated five hypotheses, as follows:

- H 1: There is a significant relationship between tangibility and student satisfaction.

- H 2: There is a significant relationship between reliability and student satisfaction.

- H 3: There is a significant relationship between responsiveness and student satisfaction.

- H 4: There is a significant relationship between assurance and student satisfaction.

- H 5: There is a significant relationship between empathy and student satisfaction.

Research Instruments and Data Collection Methods

The instrument in this research is based on Parasuraman et al (1990). The questionnaires were based on the five dimensions of service quality (tangibility, assurance, reliability, responsiveness and empathy) and used the Likert scale from 1 for strongly disagree at all to 5 for strongly agree. The questionnaires were distributed using survey method and respondents were identified through random sampling approach. The validity test was conducted using the content and face validity approached. Meanwhile the alpha coefficient for the reliability test was 0.85.

Findings and Discussion

Total of 320 students had responded and 130 or 40.6% male and 190 or 59.4% female. For age bracket between 19-25 years old are 56 or 17.5%, between 26-30 years old are 120 or 37.5%, between 31-35 years old are 64 or 20%, and lastly for aged 36 years old and above are 80 or 25%. Meanwhile, for students’ nationality, the majority of them were Malaysian that contributed 49.7% and 50.3%. International respondents include Asian, African and from Middle East at different learning institutions.

This research used Pearson Correlation and Regression Analyses. The findings for tangibility show that the mean for Malaysian is equal to 3.3069 or the absolute is equal to 3.0, this means that most of Malaysian students agree with the tangible service provided. Meanwhile, the mean of “tangibility” for international students is equal to 3.35043, this means that most of international students agree with the tangible service provided and they were more satisfied than the Malaysian students were.

The mean for “reliability” for Malaysian is around or equal to 3.4956 or the absolute is equal to 3, this means that most of the Malaysian students also agree with reliability of service provided. Whereas, the mean for reliability for international students is equal to 3.5093, this means that most of international students were more satisfied than Malaysian with reliability of services provided.

The mean for “responsiveness” for Malaysian students is equal to 3.4544 or the absolute is equal to 3.0, this means that most of the Malaysian students are satisfied with the responsiveness of service provided. For the international students, the mean of responsiveness is equal to 3.2453 or the absolute is equal to 3.0, this means that Malaysian students are more satisfied than international students are.

The mean for “assurance” for Malaysian students is equal to 3.7563 or the absolute is equal to 4, this means that most of the Malaysian students are more satisfied with the assurance of service provided. For international students, the mean of assurance is equal to 3.5885 or the absolute is equal to 3.0, this means that the Malaysian students are more satisfied than international students are.

The mean for “empathy” for Malaysian students is equal to 3.2805 or the absolute is equal to 3.0, this means that Malaysian students are satisfied with the empathy of service provided. For international students, the mean is equal to 3.3752 or the absolute is equal to 3, this means that the international students are more satisfied than the Malaysian students. Below are discussions of hypotheses.

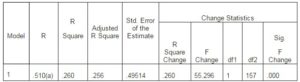

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant relationship between tangibility and students satisfaction.

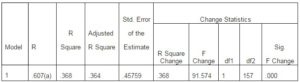

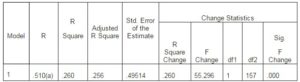

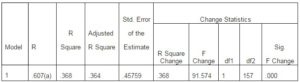

The relationship between tangibility and students satisfaction was investigated using Pearson correlation coefficient for the two groups of respondents (Malaysian and International students). The results in Table 1 indicates, a strong and positive relationship between Tangibility and student satisfaction exists among Malaysian students (R Square =.364, n=320, p<.01). This means 36% of their satisfaction is determined by tangibility.

Table 1: The Relationship between Tangibility and Customer Satisfaction (Malaysian)

Meanwhile Table 2 shows the relationship between international students satisfaction towards tangibility also shows strong and positive relationship (R square =.255, n=320, p<.01). This means that 26% of their satisfaction is determined by tangibility. However, Malaysian students are more satisfied or having stronger relationship between tangibility and satisfaction.

Table 2: The Relationship between Tangibility and Student Satisfaction (International)

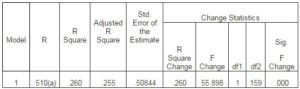

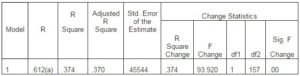

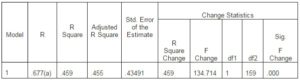

Hypothesis 2: There is a significant relationship between reliability and students satisfaction.

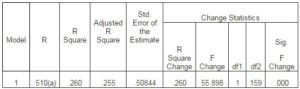

The relationship between reliability and students satisfaction was investigated using Pearson correlation coefficient for the two groups of respondents (Malaysian and International students). The results in Table 3 indicates, a strong and positive relationship between reliability and student satisfaction exists among Malaysian students (R square =.561, n=320, p<.01). This means 56% of their satisfaction is determined by reliability.

Table 3: The Relationship between Reliability and Student Satisfaction (Malaysian)

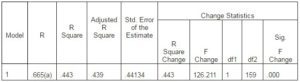

Meanwhile Table 4 shows the relationship between international students satisfaction towards reliability also shows strong and positive relationship (R square =.439, n=320, p<.01). This means that 44% of their satisfaction is determined by tangibility. However, Malaysian students are more satisfied or having stronger relationship between reliability and satisfaction.

Table 4: The Relationship between Reliability and Customer Satisfaction (International)

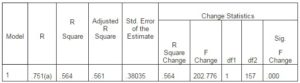

Hypothesis 3: There is a significant relationship between responsiveness and students satisfaction.

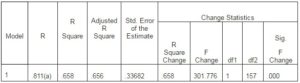

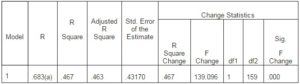

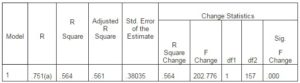

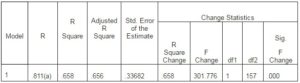

The relationship between responsiveness and students satisfaction was investigated using Pearson correlation coefficient for the two groups of respondents (Malaysian and International students). The results in Table 5 indicates, a strong and positive relationship between responsiveness and student satisfaction exists among Malaysian students (R square =.656, n=320, p<.01). This means 66% of their satisfaction is determined by responsiveness.

Table 5: The Relationship between Responsiveness and Customer Satisfaction (Malaysian)

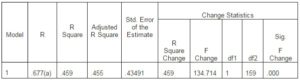

Meanwhile Table 6 shows the relationship between international students satisfaction towards responsiveness, it also shows a strong and positive relationship (R square=.455, n=320, p<.01). This means that 46% of their satisfaction is determined by responsiveness. However, Malaysian students are more satisfied or having stronger relationship between responsiveness and satisfaction.

Table 6: The Relationship between Responsiveness and Customer Satisfaction (International)

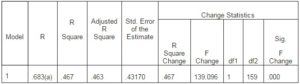

Hypothesis 4: There is a significant relationship between Assurance and students satisfaction.

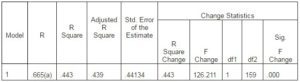

The relationship between assurance and students satisfaction was investigated using Pearson correlation coefficient for the two groups of respondents (Malaysian and International students). The results in Table 7 indicates, a moderate and positive relationship between assurance and student satisfaction exists among Malaysian students (R square =.256, n=320, p<.01). This means 26% of their satisfaction is determined by assurance.

Table 7: The Relationship between Assurance and Customer Satisfaction (Malaysian)

Meanwhile Table 8 shows that the relationship between international students satisfaction towards assurance shows strong and positive relationship (R square=.463, n=320, p<.01). This means that 46% of their satisfaction is determined by assurance. However, international students are more satisfied or having stronger relationship between responsiveness and satisfaction.

Table 8: The Relationship between Assurance and Customer Satisfaction (International)

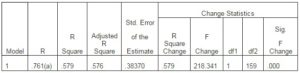

Hypothesis 5: There is a significant relationship between Empathy and students satisfaction.

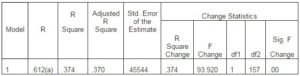

The relationship between empathy and students satisfaction was investigated using Pearson correlation coefficient for the two groups of respondents (Malaysian and International students). The results in Table 9 indicates, a moderate and positive relationship between empathy and student satisfaction exists among Malaysian students (R square =.370, n=320, p<.01). This means 37% of their satisfaction is determined by empathy.

Table 9: The Relationship between Empathy and Customer Satisfaction (Malaysian)

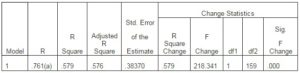

Meanwhile, Table 10 shows that the relationship between international students satisfaction towards empathy shows strong and positive relationship (R square=.576, n=320, p<.01). This means that 58% of their satisfaction is determined by empathy. However, international students are more satisfied or having stronger relationship between empathy and satisfaction.

Table 10: The Relationship between Empathy and Customer Satisfaction (International)

Conclusion

Determining and assessing students’ satisfaction with their educational experiences is not easy, but can be very helpful for the university to build strong relationship with their existing and potential students. The results indicated that both groups of students, i.e. international and domestic students, have strong relationship with depending variable. Furthermore, the results of the study declared that the areas of the university’s services quality that attain the requirements and needs of students and their expectations have better potential to build strong relationship with student satisfaction.

The results also indicate that generally higher learning institutions’ students are satisfied with the service quality performed by the Malaysian learning institutions, i.e. tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. In other words, Malaysian learning institutions have successfully implemented their strategic improvement service quality. It is an important information to build market positive perception on Malaysian learning institutions in serving its customers. It will leverage customers’ intention and brand awareness of Malaysian learning institutions’ quality, especially for foreign students. It is one of the main parts of Malaysian Higher Education Ministry’s strategic platform, which is to attract as many international students as possible to study in Malaysian universities.

Therefore, it is important for Malaysian higher learning institutions to work continuously towards ensuring that the service provided can really meet or exceed the expectation of students. For those are able to do it, will have the advantage to be more competitive and resilient. It is not about big or small but speed. Small higher learning institutions, which can make quick and better decision, have better potential to increase their market share. By doing so, higher learning institutions from Malaysia can become a major force in the industry at both Malaysia and ASEAN market.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Ahmed, I., Nawaz, M. M., Ahmad, Z., Ahmad, Z., Shaukat, M. Z., Usman, A., Wasim-ul-Rehman & Ahmed, N. (2010). “Does Service Quality Affect Students’ Performance? Evidence from Institutes of Higher Learning,” African Journal of Business Management, 4 (12). 2527-2533.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Alves, H. & Raposo M (2010). “The Influence of University Image on Students’ Behavior,” International Journal of Educational Management. 24 (1): 73-85.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C. & Lehmann, D. R. (1994). “Customer Satisfaction, Market Share, and Profitability: Findings From Sweden,” Journal of Marketing, vol.58 (July). 53- 66.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Gallifa, J. & Batalle, P (2010). “Student Perceptions of Service Quality in a Multi-Campus Higher Education System in Spain,” Quality Assurance in Education, 18 (2). 156-170

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gruber, T., Fuß, S., Voss, R. & Glaser-Zikuda, M. (2010). “Examining Student Satisfaction with Higher Education Services Using a New Measurement Tool,” International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23 (2). 105-123

Publisher – Google Scholar

Helgesen, O. & Nesset, E. (2007). “What Accounts for Students’ Loyalty? Some Field Study Evidence,” International Journal of Educational Management. 21(2). 126-43

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Ilias, A., Hasan, H. F. A., Rahman, R. A. & Yasoa, M. R (2008). “Student Satisfaction and Service Quality: Any Differences in Demographic Factors?,” International Business Research, 1(4). 131:143.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kotler, P. & Clarke, R.N. (1987). “Marketing For Health Care Organizations,” Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lee, M. C. & Hwan, I. S. (2005). ‘Relationships among Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction and Profitability in the Taiwanese Banking Industry,’ International Journal of Management, 22 (4). 635-648.

Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Mavondo, F. & Zaman, M. (2000). “Student Satisfaction with Tertiary Institution and Recommending It to Prospective Students,” 787-792.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Navarro, M. M., Iglesias, M. P. & Torres, P. R. (2005a). “A New Management Element of Universities: Satisfaction With the Courses Offered,” International Journal of Education Management, 19 (6). 505- 526

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Oliver, R. L. (1993). “A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Service Satisfaction: Compatible Goals, Different Concepts,” Advances in Services Marketing and Management, JAI Press, Greenwich. CT, vol. 2, 65-85.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Parasuraman, A., Berry, L. L. & Zeithaml, V. A. (1991). ‘Refinement and Reassessment of the SERVQUAL Scale,’ Journal of Retailing, 67 (4). 420-50

Google Scholar

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A. & Berry, L. L. (1988). “SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality,” Journal of Retailing, vol. 64, 12-40

Publisher – Google Scholar

Petruzzellis, L., D’Uggento, A. M. & Romanazzi, S. (2006). Student Satisfaction and Quality of Service in Italian Universities, Managing Service Quality, 16 (4). 349-364.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Sapri, M., Kaka, A. & Finch, E. (2009). ‘Factors that Influence Student’s Level of Satisfaction with Regards to Higher Educational Facilities Services,’ Malaysian Journal of Real Estate, 4 (1). 34:51

Tahar, E. B. M. (2008). “Expectation and Perception of Postgraduate Students for Service Quality in UTM,” Thesis, Unpublished.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Tian, R. G. & Wang, C. H. (2010). “Cross-Cultural Customer Satisfaction at a Chinese Restaurant: The Implications to China Foodservice Marketing,” International Journal of China Marketing, 1 (1). 62-72.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ugboma, C., Ogwude, I. C., Ugboma, O. & Nadi, K. (2007). “Service quality and Satisfaction Measurements in Nigerian Ports: An Exploration,” Maritime Policy & Management 34 (4). 331-346.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Usman, A. (2010). “The Impact of Service Quality on Students’ Satisfaction in Higher Education Institutes of Punjab,” Journal of Management Research, 2 (2).

Publisher – Google Scholar

Zeithaml. V. A. (2000). “Service Quality, Profitability, and the Economic Worth of Customers: What We Know and what We Need to Learn,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28 (1)., 67-85

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct