Introduction

Indonesia is experiencing a significant working-age population growth in which 30% of 53 million labor forces are women (Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration, 2014). These data reveal at least two sides, first, they indicate a positive economic development; and second, nowadays women are actively involved in the world of work either to pursue their personal career or to support their family wealth. This situation also shows an increasing number of dual-career women. Those are independent career women in the workplace and active-responsible wives/mothers at their family.

Unfortunately, this current world of work’s phenomenon generates unintentionally a balance conflict of roles and responsibilities as a career woman and a wife/mother (Karatepe and Kilic, 2007). There are two types of conflict. First, work-family conflict (WFC) occurs when the job-demands interfere in the family responsibilities, for example, due to long laboring hours and work overload, a mother has missed her children birthday party. Second, family-work conflict (FWC) occurs when family responsibilities clash with one’s job responsibilities, for instance, having a meeting with her children’s teacher, a mother has overlooked an important business meeting at her office (Netemeyer et al., 1996). WFC and FWC simply happen when someone is unable to balance and arrange her time or energy to meet both her roles and responsibilities.

Those phenomena often affect the hiring considerations or decisions, raise a doubt of role-balancing ability, and trigger a prejudice on one’s job performance, probable turnover intention, and job satisfaction. Netemeyer et al. (2004) argued that both work-family conflict and family-work conflict tend to likely have an influence on job satisfaction, turnover intention, and also job performance. The increasing conflicts that happened either at work or at family, logically, would reduce mind-concentration, trigger stress, depression, dissatisfaction, and even underperformed work, and most possibly drive to change and move to another job.

McElwain et al. (2005) argued that an increasing number of career women and dual-earner families are some triggered factors of work-family conflict or family-work conflict. Many scholars have found these kinds of conflicts in various organization contexts, such as in hotels industry (Carlson and Kacmar, 2000; Karatepe and Baddar, 2006; Karatepe and Sokmen, 2006; Karatepe and Kilic, 2007; Karatepe and Uludag, 2008; Namasivayam and Zhao, 2007; Zhao and Namasivayam, 2012), furniture manufacturers (Boyar et al., 2005), and hospitals (Anafarta, 2011; Cortese et al., 2010). Other researchers found similar conflicts in fast-food restaurants (Fong and Cheung, 2013), retail industry (Patel et al., 2006), intranet organizations (Haar, 2008), public organizations (Calvo-Salguero et al., 2010), hardware business, telecommunications and information technology, hotel and catering, travel services, and education (Rantanen et al., 2011), and many more. It reveals that handling and managing effectively this conflict is an important and strategic human-resource development.

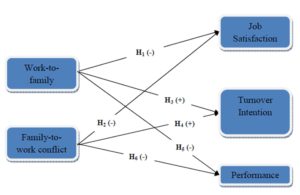

Even though many studies have explored and discussed the WFC and FWC, there are still gaps to be bridged and scientifically enriched. This study aims to examine the effect of work-family and family-work conflict on job performance, turnover intention, and job satisfaction. By having such objective, this paper specifically contributes in several important aspects. Firstly, it is to offer more evidence on the inconclusive findings of the effects of WFC and FWC on employee’s outcomes (i.e. job satisfaction, turnover intention, and job performance) as stated in prior studies (Eby et al., 2005; Netemeyer et al., 2004; O’Driscoll et al., 2004). For example, the research of Karatepe and Baddar (2006) found a significant and negative relationship between work-family conflict and satisfaction, either family satisfaction or life satisfaction. Karatepe and Kilic (2007) also discover that WFC affects negatively and insignificantly job performance. Meanwhile, related to turnover intent, Karatepe and Kilic (2007) find that FWC does not affect the frontline employees’ turnover intention positively, thus, they do not agree with Karatepe and Sokmen’s (2006) research findings. Secondly, there is a limited study of the conflicts that utilize banks’ employees as the sample (banking industry), in which a significant number of dual-role women are working in Indonesia. Thirdly, in this study, we develop a structural equation model (SEM) to measure the influence of both WFC and FWC on job satisfaction, job performance, and turnover intention. The use of SEM approach provides more sophisticated and reliable findings.

The study discusses the relevant theories, reviews the literatures, and develops the hypotheses in Section 2. Section 3 presents the research methodology and data while Section 4 reveals the empirical findings and discussions. Finally, Section 5 provides the conclusion and recommendation.

Literature Review And Hypotheses

This study centers on two main relevant theories, which are work-family conflict and family-work conflict. Those theories specifically discuss the role-pressure domain, whether from work or family.

Work-Family Conflict and Family-Work Conflict

Work-family conflict (WFC) is a “form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect. That is, participation in the work (family) role becomes more difficult due to virtue of participation in the family (work) role” (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). WFC occurs when there is a discrepancy between real situation and people’s expectation that will disturb and decrease their role’s performance at work or family (Greenhaus et al., 2006). In addition, WFC is conceptualized as the consequence of “resources being lost in the process of juggling both work and family roles” (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999). Furthermore, Trachtenberg et al. (2009) argued that WFC was a term “used to illustrate the competition between one’s professional role and one’s personal and family life.” The work-family conflict is also considered as a bi-directional conflict. It is divided into two main concepts. First, work can be interfered by family (WIF) and second, family can be interfered by work (FIW) (Frone et al., 1992).

Conceptually, there is a contrary concept between work-family conflict (WFC) and family-work conflict (FWC) while they are actually related in terms of inter role conflict (Frone et al., 1992; Netemeyer et al., 1996). WFC refers to “a form of inter role conflict in which the general demands of time devoted to and strain created by the job, interfere with performing family-related responsibilities.” Meanwhile, FWC refers to “a form of inter role conflict, in which the overall demands of time devoted to and strain created by the family, interfere with performing work-related responsibilities” (Netemeyer et al., 1996). In other words, WFC happens when someone is unable to do his or her work activities because of his or her family responsibilities, whereas FWC happens when family activities interfere with work responsibilities.

Job Satisfaction

Locke (1969) argues that job satisfaction is “a pleasurable emotional state that results from an individual appraisal of one’s job.” According to Brief (1998), job satisfaction is “an internal state that is expressed by affectively and/or cognitively evaluating an experienced job with some degree of favor or disfavor.” Spector (1997) defines job satisfaction as an attitude that related with the level to which people like or dislike their job, feel satisfied or not with their work performance. Negative attitude reflects a despicable level of job satisfaction that will lead to absenteeism, turnover intent, and also low productivity. On the other hand, worker’s commitment, loyalty and high productivity are the results of positive attitude and high level of job satisfaction.

Ivancevich et al. (1997) argue that job satisfaction relates to the employees’ reaction and perception about their job responsibility and expectation regarding the organization’s feedback to what they have done. As a consequence, employees’ job satisfaction connects with the pleasure and contentment that they receive from their job and organization as well. Diaz-Serrano and Cabral Vieira (2005) defined the concept about job satisfaction as the overall feeling or emotional expression that would influence employees’ decision to stay or to leave a job and move to another more satisfying job (Gazioglu and Tansel, 2006). Employees, who feel satisfied with their job, will have good commitment and loyalty to the organization and, on the other hand, intention to leave will increase as they are dissatisfied with their job.

Turnover Intention

According to Berndt (1981), turnover intention is the employee’s statements or actions regarding a specific behavior of interest. Turnover intention indicates the possibility and also willingness of the individual/employee to change and move their job to another job or organization within a certain period (Souse-Poza and Henneberger, 2004). Similarly, turnover intention is an employee’s aspiration to find a new better job, because of their dissatisfaction with the present job. Therefore, this intention to leave reflects an active employee’s evaluation and observation on job alternatives. It also becomes a problem indicator, whether it happens inside the employee’s life or the organization one. Tett and Meyer (1993) support this exposition by stating turnover intention as the employee’s awareness and propensity to desist and leave the organization.

Job Performance

Job performance is defined as “the level of productivity of an individual employee, relative to his or her peers, on several job-related behaviors and outcomes” (Babin and Boles, 1998). In terms of organization context, employees with high performance usually get promotions more easily. They also have better career opportunities than others with low performance (VanScotter et al., 2000). Moreover, in their research model, Christen et al. (2006) argued that employees’ effort and ability determined the level of job performance. They also claim a different concept of effort and performance, which is an input to work while job performance is an output from those efforts. Generally, job performance is related to the employees’ ability to carry out their job well or not. If they perform highly, it means they feel satisfied with what they have finished, and the probability to turnover becomes lower. On the contrary, an employee with poor performance is normally dissatisfied with their job, which leads to an increased turnover intention (Tuten and Neidermeyer, 2004).

Hypothese

Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction

In most of the studies, work-family conflict has a significant and negative influence on the employees’ job satisfaction (Frone et al., 1992; Netemeyer et al., 1996; Boles et al., 1997; Carly et al., 2002; Wayne et al., 2004; Kinnunen et al., 2006; Karatepe and Kilic, 2007; Calvo-Salguero et al., 2010; Carlson et al., 2010; Zhao and Namasivayam, 2012). Those prior studies revealed that interferences between work activities and family responsibilities finally would create job dissatisfaction, bring employees to dislike their job, and lead to underperforming job quality. The research of Karatepe and Kilic (2007) also reported that work-family conflict would decrease frontline’s job satisfaction in Northern Cyprus hotels. These findings were confirmed by the statement “excessive workloads have hampered my efforts to meet family needs” which has driven to a lower job satisfaction (WIF – work interfered family). On the contrary, those scholars also mentioned the FIW – family interfered work, which happens when employees’ family roles create restriction for them to do their work tasks. It also will trigger job dissatisfaction (Zhao and Namasivayam, 2012). Therefore, based on those arguments, the first hypothesis is: H1: Work-family conflict has a negative influence on job satisfaction.

Family Work Conflict and Job Satisfaction

In line with work-family conflict, many researchers argued that family-work conflict had a significant and negative influence on job satisfaction (Netemeyer et al., 1996; Carly et al., 2002; Carlson et al., 2010), family satisfaction (Karatepe and Baddar, 2006; Wayne et al., 2004), and marital satisfaction (Kinnunen and Mauno, 1998). Karatepe and Sokmen (2006) supported this adverse influence of family-work conflict on job satisfaction by testing frontline employees in three, four, and five star-category hotels located in Ankara (Turkey) as the sample. Furthermore, employees, who could not dispense their time to fulfill family needs, would lead to high level of disruption, not only at home but also at the office. Since family and works are critical things for people, especially for adult, these conflicts will finally give significant and unfavorable influence, either on family or job satisfaction (Karatepe and Kilic, 2007). Therefore, based on those arguments, the second hypothesis is: H2: Family-work conflict has a negative influence on job satisfaction.

Work-Family Conflict and Turnover Intention

Many researchers have reported many findings of the influence of work-family conflict on the employees’ turnover intention (Netemeyer et al., 1996; Boyar et al., 2003; Kinnunen et al., 2004; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran, 2005; Karatepe and Baddar, 2006; Karatepe and Uludag, 2008). They suggest that there was a significant and positive influence between those two variables, meaning if conflicts either work-family conflict or family-work conflict increased, then an elevated turnover intention level would follow. The research of Karatepe and Baddar (2006) supported this argument. They found W-FCON (work-family conflict) and F-WCON (family-work conflict) were positively related to frontline employees’ TURNINT (turnover intention). Furthermore, a previous study by Blomme et al. (2010) found that both WFC and organizational support are the predictors of employee turnover intention in the hospitality industry. Therefore, based on those arguments, the third hypothesis is: H3: Work-family conflict has a positive influence on turnover intention.

Family-Work Conflict and Turnover Intention

Similarly with work-family conflict, the influence of family-work conflict on turnover intention also becomes an interesting topic for many studies (Boyar et al., 2003; Mesmer-Magnus et al., 2005; Karatepe and Baddar, 2006; Karatepe and Uludag, 2008). As explained before, the influence of family-work conflict and turnover intention is in the same direction. It means an increasing of one variable would go along with the other variable. Meanwhile, Karatepe and Uludag (2008) in their research also proved this connection between the two variables. They showed that both work-family conflict and family-work conflict were positively related to frontline employees’ turnover intentions. Therefore, based on those arguments, the fourth hypothesis is: H4: Family-work conflict has a positive influence on turnover intention.

Work-Family Conflict, Family-Work Conflict and Job Performance

Generally, in developing countries, there are two variables (i.e. work-life conflict and job overload) connected to works giving significant effect on employees’ performance (Ashfaq et al., 2013). Those variables (i.e. work-life conflict and job overload) also related to long working hours that need a high level of energy to fulfill. It is connected with job demand exceeding human ability (-employees have to do many tasks with a very limited time-). It deals with the request from organization to do hard and fast work, and many other things, at the end; it will drive unfavorable reactions, such as stress, tardiness, dissatisfaction, or nonattendance behaviors (Boyar et al., 2005). To analyze these issues, there are several studies striving to find out the valid influence and also give an empirical support to those conflicts on job performance, although still in a limited number (Netemeyer et al., 1996). For example, the research of Patel et al. (2006) rejects the relationship between family-work conflict and job performance. On the contrary, Ashfaq et al. (2013) reported that employees’ performance was affected by work-life conflict and work overload in the banking sector. Therefore, based on those arguments, the fifth and sixth hypotheses are: H5: Work-family conflict has a negative influence on job performance; H6: Family-work conflict has a negative influence on job performance.

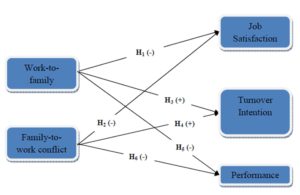

Figure1: Research Model

Method

This study employed 334 banks’ employees as the sample in four Indonesian banks, which are two public/government-owned banks (Mandiri and BNI) and two private-owned ones (Citibank and BII). The study asked respondents to fill in and answer the questionnaire in order to find out whether their works’ pressure will drive conflict at home or their family problems will create disturbance at work. Then, the study analyzes whether these conflicts will affect employees’ job satisfaction, turnover intention, and job performance or not.

In this study, work-family and family-work conflicts are independent variables. There are five items used to measure each conflict adapted from Boles et al. (2001). To measure the first dependent variable, job satisfaction, this study adopted the Elerina Maria’s (2008) nine items. For turnover intention, it utilized three items that were developed by Allen and Meyer (1990). Finally, the last dependent variable (job performance) was operationalized by seven items of Williams and Anderson’s (1991) research. All the variables used five-point Likert-type scales (from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree).

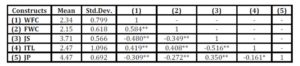

Table 1: Inter-correlations

Note: ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; WFC = work-family conflict; FWC = family-work conflict; JS = job satisfaction; ITL = intention to leave; JP = job performance

The correlation of independent variables, i.e. work-family and family-work conflicts, reveals that there is no severed multicollinearity, due to the fact that the value (0.584) is still below the maximum value (0.80), which indicates the existence of multicollinearity (Gujarati, 1995). The significant and negative correlation between both WFC and FWC with job satisfaction implies an increase of those conflicts will decrease employees’ satisfaction. Furthermore, the correlation between those conflicts with the intention to leave shows a considerable possibility for an employee to leave their job if they have frequently conflicted with their job or with their family. Meanwhile, employees’ performance will also decrease if their conflicts at office/family arise, as shown by the negative and significant correlation between both types of conflicts with job performance (Table 1).

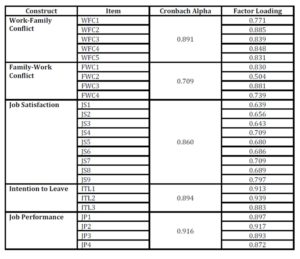

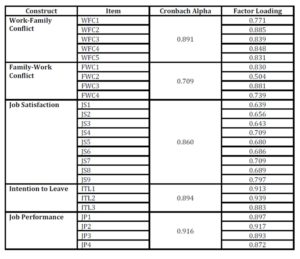

Table 2: Test of Construct’s Validity and Reliability

Table 2 presents the results of constructs’ validity and reliability test. This study applied factor analysis to test each construct’s validity and proceeded with the estimation of reliability (alpha) of each variable. The factor analysis procedure followed the work of Tabachnick and Fidell (1996) in which the study repeated the procedure until there were no invalid statement-items according to the criteria set out in SPSS 20. An item would be retained if the factor loading was equal to or greater than 0.5. After the validity test, this study examined the variable reliability by using the Cronbach’s Alpha. It was to test the consistency of the overall respondents in answering the statement-items of a particular variable. The Cronbach’s Alpha value should be commonly bigger than 0.6. The greater value of Cronbach’s Alpha is the better reliability of the variables. From the validity test, there are four invalid items: one item of family-work conflict (FWC5) and three items of job performance (JP5, JP6, JP7), while other constructs are reliable.

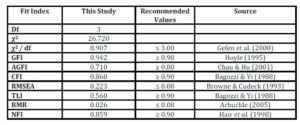

Table 3: Fit Indices for the Measurement Model

This study employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with Amos 20.0 to test the hypothesized relationship among variables. The SEM enables a researcher to estimate simultaneously the multiple regression equations in a single framework, and examine the interrelated relationship, both direct and indirect relationship between several latent constructs in the same decision context (Hair et al., 2006). The measurement model indices reveal that the proposed model generally is fit and parsimony. Thus, the fit test results confirm that all variables can be tested and measured in the proposed model (Table 3).

Findings and Discussion

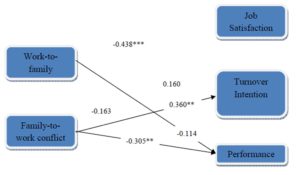

Figure 2 shows the hypotheses testing’s results. In this study, the result of the first hypothesis test reveals the negative influence of work-family conflict on job satisfaction (β = -0.438; p < 0.01). In other words, employees with work-family conflict will have a lower level of job satisfaction. It supports the works of Frone et al. (1992), Netemeyer et al. (1996), Boles et al. (1997), Carly et al. (2002), Wayne et al. (2004), Kinnunen et al. (2006), Karatepe and Kilic (2007), Calvo-Salguero et al. (2010), Carlson et al. (2010) and Zhao and Namasivayam (2012). It shows that employees’ role conflict at work is destructive and creates job dissatisfaction for them.

This finding is contrary to the rejection of the second hypothesis (β = -0.163; p > 0.1). It reveals that family-work conflict does not give significant and negative effect on the employees’ job satisfaction. This result does support the prior findings of Netemeyer et al. (1996), Carly et al. (2002), and Carlson et al. (2010). Logically, employees who have problems with their family become more emotional do not have any mind-concentration and even stress, then it will reduce their job satisfaction. However, for an employee who is work-oriented (workaholic) and has a high professionalism with her work, she would try to focus and finish the duties; afterwards it directly leads to increased job satisfaction.

Note: ***p< 0.01 **p< 0.05 *p< 0.1

Figure 2: Hypotheses Testing

For the third hypothesis test, the result shows that work-family conflict does not affect turnover intention (β = 0.160; p > 0.1), then the study rejects the third hypothesis. This result describes that work-family conflict, which is triggered by work pressure, does not give any influence on whether an employee would like to move and find another job or not. The findings are not in line with the prior studies of Netemeyer et al. (1996), Boyar et al. (2003), Kinnunen et al. (2004), Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran (2005), Karatepe and Baddar (2006), and Karatepe and Uludag (2008). Employees perceive work pressure as a challenge for them, and it should be handled wisely. In addition, they consider work competition and pressure as a chance to get a new better job.

On the contrary, the fourth hypothesis found that family-work conflict has a positive and significant effect on the turnover intention (β = 0.360; p < 0.05). As conflict at home increased then the intent to turnover would also upsurge. It supports the prior studies of Boyar et al. (2003), Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran (2005), Karatepe and Baddar (2006), and Karatepe and Uludag (2008). However, an employee, who gets family pressure, generally decides to move to other jobs because of some considerations, such as family-oriented workers who attempt to balance their dual-roles. If they could not manage and balance their family responsibilities, then it would be better for them to move and find new jobs.

The test of the fifth hypothesis demonstrates that there is no effect of work-family conflict on job performance (β = -0.114; p > 0.1). This result reveals that employees are still committed to their work responsibilities, although they have to balance their dual-roles either at work or at family. The finding is not in line with the works of Netemeyer et al. (1996) and Boyar et al., (2005). In contrary to the sixth hypothesis, the finding indicates a negative and significant influence of family-work conflict on job performance (β = -0.305; p < 0.05). Employees’ family conflicts will trigger them to become out of focus with their job and finally they affect their job performance.

These empirical findings lend some important business implications. Since the sample is dual-roles women in banking industry, which is one of the main involved-working women sectors, special attention for relaxing the pressure is a must. Banks as involved-organizations could provide some supports for their employees, such as setting child-care/playgroup facilities for women with early-age children, flexible work schedule, and supportive working environment. On the other side, the government could offer important support to working women by regulating special leave for married-working men to part in family activities, such as paternity and child sick leave. Human-resource banking practices should be more selective and proactive in designing job assignment and position between single and married women. A fit arrangement considering marital and family status would generate reduced pressure and conflict between work and family for dual-roles women.

Conclusion

This study examines the effect of work-family and family-work conflict on job performance, turnover intention, and job satisfaction. By using a sample of 334 dual-roles women in four Indonesian banks and analyzing the six proposed hypotheses, it found some important results. Work-family conflict (WFC) affects job satisfaction negatively and significantly, meanwhile, family-work conflict (FWC) does not influence considerably. FWC encourages married and working women to have higher intention of leaving their job significantly. On the other side, WFC does the same insignificantly. In the context of job performance, both conflicts have similar effects; however, only family-work conflict has a significant influence.

The empirical findings may not be generalized to other sectors/industries or countries with low involvement of dual-roles women. The country’s openness level and society cultures and norms play an important role in encouraging women to be more actively involved in the world of work. Therefore, this study suggests the inclusion of other sectors or industries’ and jobs’ characteristics, such as non-service sectors (manufactures, military) and self-employed businesses. It is noteworthy for testing the effect of job characteristics as the moderating variables. It is to see whether certain job characteristics can mitigate the unfavorable effects or not.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

1. Allen, TD. and Meyer, JP. (1990), ‘The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 63 (1), 1-19.

Publisher – Google Scholar

2. Anafarta, N. (2011), ‘The Relationship between Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction: A Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Approach,’ International Journal of Business and Management, 6 (4), 168-177.

Publisher – Google Scholar

3. Arbuckle, JL. (2005), AMOS 6.0 User’s Guide, Spring House, AMOS Development Corp, PA.

4. Ashfaq, S., Mahmood, Z. and Ahmad, M. (2013), ‘Impact of Work-Life Conflict and Work Overload on Employee Performance in Banking Sector of Pakistan,’ Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 14 (5), 688-695.

Google Scholar

5. Babin, B. and Boles, JS. (1998), ‘Employee Behavior in A Service Environment: A Model and Test of Potential Differences between Men and Women,’ Journal of Marketing, 62 (2), 77-91.

Publisher – Google Scholar

6. Bagozzi, RP. and Yi, Y. (1988), ‘On The Evaluation of Structural Equation Models,’ Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16 (1), 74-94.

Publisher – Google Scholar

7. Berndt, TJ. (1981), ‘Effects of Friendship on Prosocial Intentions and Behavior,’ Child Development, 53 (2), 636-643.

Publisher – Google Scholar

8. Blomme, RJ., Rheed, AV. and Tromp, DM. (2010), ‘Work-Family Conflict as A Cause for Turnover Intentions in The Hospitality Industry,’ Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10 (4), 269-285.

Publisher – Google Scholar

9. Boles, JS., Johnston, MW. and Hair, JF, Jr. (1997), ‘Role Stress, Work-Family Conflict and Emotional Exhaustion: Inter-Relationships and Effects on Some Work Related Consequences,’ Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 17 (1), 17–28.

Google Scholar

10. Boles, JS., Howard, WG. and Donofrio, HH. (2001), ‘An Investigation into The Inter-relationships of Work-Family Conflict, Family-Work Conflict and Work Satisfaction,’ Journal of Managerial Issues, 13 (3), 376-90.

Google Scholar

11. Boyar, SL., Maertz, CP, Jr., Pearson, AW. and Keough, S. (2003), ‘Work-Family Conflict: A Model of Linkages between Work and Family Domain Variables and Turnover Intentions,’ Journal of Managerial Issues, 15 (2), 175–190.

Google Scholar

12. Boyar, SL., Maertz, CP, Jr. and Pearson, AW. (2005), ‘The Effects of Work-Family Conflict and Family-Work Conflict on Non-Attendance Behaviors,’ Journal of Business Research, 58 (7), 919-925.

Publisher – Google Scholar

13. Brief, AP. (1998), Attitudes in and Around Organizations, Thousand Oaks, Sage, CA.

Google Scholar

14. Browne, MW. and Cudeck, R. (1993), Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit, In KA. Bollen and JS. Long (Eds.), Testing Structural Equation Models, 136-162, Newsbury Park, Sage, CA.

15. Calvo-Salguero, A., Carrasco-Gonzalez, AM. and Maria, J. (2010), ‘Relationship between Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction: The Moderating Effect of Gender and The Salience of Family and Work Roles,’ African Journal of Business Management, 4 (7), 1247-1259.

Google Scholar

16. Carlson, DS. and Kacmar, KM. (2000), ‘Work-Family Conflict in The Organization: Do Life Role Values Make A Difference?,’ Journal of Management, 26 (5), 1031-1054.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17. Carlson, DS., Grzywacz, JG. and Kacmar, KM. (2010), ‘The Relationship of Schedule Flexibility and Outcomes via The Work-Family Interface,’ Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25 (4), 330-355.

Publisher – Google Scholar

18. Carly, BS., Allen, TD. and Spector, PE. (2002), ‘The Relation between Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction: A Finer Grained Analysis,’ Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 60 (3), 336-353.

Publisher – Google Scholar

19. Chau, PYK. and Hu, P. (2001), ‘Information Technology Acceptance by Individual Professionals: A Model Comparison Approach,’ Decision Sciences, 32 (4), 699-719.

Publisher – Google Scholar

20. Christen, M., Iyer, G. and Soberman, D. (2006), ‘Job Satisfaction, Job Performance and Effort: A Reexamination Using Agency Theory,’ Journal of Marketing, 70 (1), 137-150.

Publisher – Google Scholar

21. Cortese, CG., Colombo, L. and Ghislieri, C. (2010), ‘Determinants of Nurses’ Job Satisfaction: The Role of Work-Family Conflict, Job Demand, Emotional Charge and Social Support,’ Journal of Nursing Management, 18 (1), 35-43.

Publisher – Google Scholar

22. Diaz-Serrano, L. and Cabral-Vieira, JA. (2005), Low Pay, Higher Pay and Job Satisfaction within The European Union: Empirical Evidence from Fourteen Countries, Maynooth and University of The Azores – Department of Economics and Business, National University of Ireland.

Google Scholar

23. Eby, LT., Casper, WJ., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux, C. and Brinley, A. (2005), ‘Work and Family Research in IO/OB: Content Analysis and Review of The Literature (1980-2002),’ Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 124-197.

Google Scholar

24. Elerina Maria, DT. (2008), Analisis Pengaruh Kepuasan Kerja, Komitmen Organisasi dan Motivasi terhadap Kinerja Manajerial Pemerintah Daerah, Tesis UGM.

Google Scholar

25. Fong, VWS. and Cheung, R. (2013), An Empirical Study of The Factors Affecting Work-Family Conflict and Quit Intention of Managerial Staff in Fast-Food Restaurants, Paper presented in International Conference on Business and Information, Bali (Indonesia), July 7-9, Conference Proceedings 10 (1), 515-536.

26. Frone, MR., Russell, M. and Cooper, ML. (1992), ‘Antecedents and Outcomes of Work-Family Conflict,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65-78.

Publisher – Google Scholar

27. Gazioglu, S. and Tansel, A. (2006), ‘Job Satisfaction in Britain: Individual and Job related Factors,’ Applied Economics, 38 (10), 1163-1171.

Publisher – Google Scholar

28. Gefen, D., Straub, D. and Boudreau, MC. (2000), ‘Structural Equation Modeling and Regression: Guidelines for Research Practice,’ Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4 (7), 1-70.

Google Scholar

29. Grandey, AA. and Cropanzano, R. (1999), ‘The Conservation of Resources Model Applied to Work-Family Conflict and Strain,’ Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54 (2), 350-370.

Publisher – Google Scholar

30. Greenhaus, JH. and Beutell, NJ. (1985), ‘Sources of Conflict between Work and Family roles,’ Academy of Management Review, 10 (1), 76-88.

Publisher – Google Scholar

31. Greenhaus, HJ., Tammy, DA. and Spector, PE. (2006), ‘Health Consequences of Work-Family: The Dark Side of The Work-Family Interface,’ Research in Occupational Stress and Well-Being, 5, 61-98.

Google Scholar

32. Gujarati, DN. (1995), Basic Econometrics, Mc Graw Hill, New York.

33. Haar, J. (2008), ‘Work-Family Conflict and Job Outcomes: The Moderating Effects of Flexitime Use in A New Zealand Organization,’ New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 33 (1), 38-54.

Google Scholar

34. Hair, JF, Jr., Anderson, RE., Tatham, RL. and Black, WC. (1998), Multivariate Data Analysis, (5th Edition), Upper Saddle River, Prentice Hall, NJ.

35. Hair, JF, Jr., Anderson, RE., Tatham, RL. and Black, WC. (2006), Multivariate Data Analysis (6th Ed.), Upper Saddle River, Prentice Hall, NJ.

Google Scholar

36. Hoyle, RH. (1995), Structural Equation Modeling, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, Inc., CA.

37. Ivancevich, J., Olelelns, M. and Matterson, M. (1997), Organizational Behavior and Management, Irwin, Sydney.

38. Karatepe, OM. and Baddar, L. (2006), ‘An Empirical Study of The Selected Consequences of Frontline Employees’Work-Family Conflict and Family-Work conflict,’ Tourism Management, 27 (5), 1017–1028.

Publisher – Google Scholar

39. Karatepe, OM. and Kilic, H. (2007), ‘Relationships of Supervisor Support and Conflicts in The Work-Family Interface with The Selected Job Outcomes of Frontline Employees,’ Tourism Management, 28 (1), 238–252.

Publisher – Google Scholar

40. Karatepe, OM. and Sokmen, A. (2006), ‘The Effects of Work Role and Family Role Variables on Psychological and Behavioral Outcomes of Frontline Employees,’ Tourism Management, 27 (2), 255–268.

Publisher – Google Scholar

41. Karatepe, OM. and Uludag, O. (2008), ‘Affectivity, Conflicts in The Work-Family Interface, and Hotel Employee Outcomes,’ International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27 (1), 30-41.

Publisher – Google Scholar

42. Kinnunen, U. and Mauno, S. (1998), ‘Antecedents and Outcomes of Work-Family Conflict among Employed Women and Men in Finland,’ Human Relations, 51 (2), 157-177.

Publisher – Google Scholar

43. Kinnunen, U., Geurts, S. and Mauno, S. (2004), ‘Work-to-Family Conflict and Its Relationship with Satisfaction and Well-Being: A One-Year Longitudinal Study on Gender Differences,’ Work & Stress, 18 (1), 1-22.

Publisher – Google Scholar

44. Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., Geurts, S. and Pulkkinen, L. (2006), ‘Types of Work-Family Interface: Well-Being Correlates of Negative and Positive Spillover between Work and Family,’ Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47 (2), 149-162.

Publisher – Google Scholar

45. Locke, EA. (1969), ‘What is job satisfaction?,’ Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4 (4), 309-336.

Publisher – Google Scholar

46. McElwain, AK., Korabik, K. and Rosin, HM. (2005), ‘An Examination of Gender Differences in Work–Family Conflict,’ Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 37 (4), 283-298.

Publisher – Google Scholar

47. Mesmer-Magnus, JR. and Viswesvaran, C. (2005), ‘Convergence between Measures of Work-to-Family and Family-to-Work Conflict: A Metaanalytic Axamination,’ Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67 (2), 215-232.

Publisher – Google Scholar

48. Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration (2014), ‘Situasi Ketenagakerjaan Umum di Indonesia [Current Situation of Indonesia’s Workforce]’. [Online], [Retrieved September 17, 2014], http://pusdatinaker.balitfo.depnakertrans.go.id/userfiles/l5ru_20140626_ jabatan%20fungsional%20umum%20919%20update24juni2014.pdf

49. Namasivayam, K. and Zhao, X. (2007), ‘An Investigation of The Moderating Effects of Organizational Commitment on The Relationships between Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction among Hospitality Employees in India,’ Tourism Management, 28 (5), 1212-1223.

Publisher – Google Scholar

50. Netemeyer, RG., Boles, JS. and McMurrian, R. (1996), ‘Development and Validation of Work-Family Conflict and Family-Work Conflict Scales,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 81 (4), 400-410.

Publisher – Google Scholar

51. Netemeyer, RG., Brashear-Alejandro, T. and Boles, JS. (2004), ‘A Crossnational Model of Job-related Outcomes of Work Role and Family Role Variables: A Retail Sales Context,’ Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32 (1), 49-60.

Publisher – Google Scholar

52. O’Driscoll, MP., Brough, P. and Kalliath, TJ. (2004), ‘Work/Family Conflict, Psychological Well-Being, Satisfaction and Social Support: A Longitudinal Study in New Zealand,’ Equal Opportunities International, 23 (1/2), 36-56.

Publisher – Google Scholar

53. Patel, CJ., Govender, V., Paruk, Z. and Ramgoon, S. (2006), ‘Working Mothers: Family-Work Conflict, Job Performance and Family/Work Variables,’ Journal of Industrial Psychology, 32 (2), 39-45.

Publisher – Google Scholar

54. Rantanen, M., Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U. and Rantanen, J. (2011), ‘Do Individual Coping Strategies Help or Harm in The Work-Family Conflict Situation? Examining Coping as A Moderator between Work-Family Conflict and Well-Being,’International Journal of Stress Management, 18 (1), 24-48.

Publisher – Google Scholar

55. Sousa-Poza, A. and Henneberger, F. (2004), ‘Analyzing Job Mobility with Job Turnover Intentions: An International Comparative Study,’ Journal of Economic Issues, 38 (1), 113-137.

Google Scholar

56. Spector, PE. (1997), Job satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes and Consecuences, Thousand Oaks, Sage, CA.

Google Scholar

57. Tabachnick, BG. and Fidell, LS. (1996), Using Multivariate Statistics, Harper Collins College Publishers.

58. Tett, RP. and Meyer, JP. (1993), ‘Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Turnover Intention and Turnover: Path Analyses based on Meta-Analytic Findings,’ Personnel Psychology, 46 (2), 259-293.

Publisher – Google Scholar

59. Trachtenberg, VJ. Anderson, S. and Sabatelli, R. (2009), ‘Work-Home Conflict and Domestic Violence: A Test of A Conceptual Model,’ Journal of Family Violence, 24 (7), 471-483.

Publisher – Google Scholar

60. Tuten, TL. and Neidermeyer, PE. (2004), ‘Performance, Satisfaction and Turnover in Call Centers: The Effects of Stress and Optimism,’ Journal of Business Research, 57 (1), 26-34.

Publisher – Google Scholar

61. Van Scotter, J., Motowidlo, SJ. and Cross, TC. (2000), ‘Effects of Task Performance and Contextual Performance on Systemic Rewards,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 85 (4), 526-535.

Publisher – Google Scholar

62. Wayne, JH., Musisca, N. and Fleeson, W. (2004), ‘Considering The Role of Personality in The Work-Family Experience: Relationships of The Big Five to Work-Family Conflict and Facilitation,’ Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64 (1), 108-130.

Publisher – Google Scholar

63. Williams, LJ. and Anderson, SE. (1991), ‘Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship and In-Role Behaviors,’ Journal of Management, 17 (3), 601-617.

Publisher – Google Scholar

64. Zhao, X. and Namasivayam, K. (2012), ‘The Relationship of Chronic Regulatory Focus to Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction,’ International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31 (2), 458-467.

Publisher – Google Scholar