Introduction

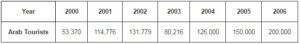

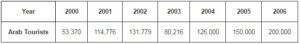

Tourism has become one of the major aspects of the economic sector that is generating a huge income and revenue to both individual and government of many countries where tourism is well promoted (Mat et al., 2009). Until 9/11 incident, many Arab tourists tend to go for tourism adventure or vacation in the Western world which includes the U.S.A and Europe. However, the incident of 9/11 has changed the baton where many Arabs now turn to the Asia countries in particular Malaysia for their tourism pleasure or adventure (Mat et al., 2009). The data provided by Mat et al., (2009) indicate that Arab tourists are the highest spenders among all other tourists in Malaysia. For instance, an average Arab is found to spend a minimum of RM 5,000.00 per trip (Salman and Hasim, 2012, Mat et al., 2009) The data in table 1 below provides detail information about the Arab tourists in Malaysia (Salman and Hasim, 2012).

Table 1: The Trend of Arab Tourist Coming to Malaysia

Furthermore, in order to embark on tourism adventure or pleasure, the potential tourists need clear information about the tourism sector or activities of that particular country they intend to go for their tourism adventure. Not on that but also, they need to search for information relating to the tourism, and the channel or method of getting this information are very crucial to both the tourists and as well as to the tourism providers. In view of this, two major issues confronting Arab tourists are being identified and discussed as they formed the basis upon which this study is being conducted.

First, the ineffectiveness of the information channels used by the Arab travelers to search for tourism information is an issue to be investigated. A critical observation shown that the information channels used by Arab tourists has been judged not to be effective due to the inability of the users to actually identify which channel of information they used. In the academic domain, Grønflaten (2009) has identified the problem with the communication method (otherwise known as information channel) used by the tourists. He argued that until now the tourists are yet to clearly show how they obtained their tourism information and how the information is being distributed.

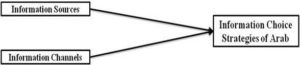

Concerning the information sources, authors (Grønflaten, 2009, Fodness and Murray, 1997) have acknowledged the problem of information source by the tourists that is, who provides information about tourism to them? To this end, Fodness and Murray (1997) claim that the most pressing need is for more systematic research describing how and why travelers use different information search strategies. In the light of this, they suggested that future research is required in order to examine travelers’ use of different information search strategies through the analysis of perceptions of the alternatives available to them for trip planning, and that such research should address the dimensions underlying search strategy preferences. For example, it is important to know what causes different tourists to choose specific sources to plan their trips (Fodness and Murray, 1997). Besides, the previous studies in the tourism domain have failed to clearly establish which factor determines the information choice strategy (Grønflaten, 2009, Jansen and Rieh, 2010). For instance, Jansen and Rieh (2010) noted that until now authors have failed to determine between information sources and channels, and these are among the most important theoretical construct of the information sciences. Also, further review indicates that study such as Case (2012); Fodness and Murray (1997); Gitelson and Crompton (1983); Raitz and Dakhil (1989) have equally failed to distinguish between information sources and channels and how both constructs separately determine the information choice strategy of the tourists. Researchers tend to use the term information source’ whether they are referring to the provider of the information or the communication method (Case, 2012, Fodness and Murray, 1997, Gitelson and Crompton, 1983, Raitz and Dakhil, 1989). One of the objectives of this study is to address this gap by making a clear distinction between information sources and information channels and to the extent or how each variable individually determine the information choice strategy. In view of the foregoing discussion, the present study therefore investigates the influence of information source and information channels on the information choice strategy of the Arab tourists.

Literature Review

Tourism Within the context of this study, information source is described as the origin of the information about the tourism destination of the tourists or pleasure travelers (Abd Aziz and Ariffin, 2009), and these sources may include friend/relatives, media, internet, travel agents etc. (Fodness and Murray, 1997). Besides this, Fodness and Murray (1997) noted that information sources can also be internal or external depending on where the information seeker obtained his information.

As for information channels, it is described by Rogers (1983 cited Sill, 1958) as the means by which messages (tourism information) get from one individual (tourism information provider) to another (tourist seeking tourism information). According to Rogers (1986), the information channel would include mass media channels such as radio, television, newspapers etc. Accordingly, information choice strategy is concerned with the decision about the tourism destination of the tourists. It includes tourists choosing among alternative tourism destinations available to him (Hamilton and Lau, 2005).

Empirical findings by previous studies such as Grønflaten (2008; 2009) and Jansen and Rieh (2010) have acknowledged that traveler’s choice of information is affected or determined by a number of factors such as information source and information channels. For instance, a qualitative study conducted by (Grønflaten, 2008) on factors that affect traveler’s choice of information revealed that information source and information channels are among the identified factors. Thus, information source and information channels are good determinants of information choice strategy of the travelers. This is also in line with the Media Richness theory which emphasizes on the richness of the information source and information channels to transmit or share information between people (Tan and Arnott, 1999). Also, another study by Grønflaten (2009) on information channels and travelers choice of information found that information sources such as travel agents and service providers; and information channels such as face-to-face and the internet significantly affect travelers’ choice of information strategy.

However, studies (Case, 2012, Jansen and Rieh, 2010, Fodness and Murray, 1997, Gitelson and Crompton, 1983, Raitz and Dakhil, 1989) on this issue have failed to distinguish between the source that is providing the information and the channel through which it is communicated. For instance, the study conducted by Jansen and Rieh (2010) noted that until now authors have failed to distinguish between information sources and channels, and these are among the most important theoretical construct of the information sciences. Also, further review indicates that study such as Case (2012); Fodness and Murray (1997); Gitelson and Crompton (1983); Raitz and Dakhil (1989) have equally failed to distinguish between information sources and channels. Researchers tend to use the term information source’ whether they are referring to the provider of the information or the communication method (Case, 2012, Fodness and Murray, 1997, Gitelson and Crompton, 1983, Raitz and Dakhil, 1989).

Furthermore, Grønflaten (2009) has identified the problem with the communication method (otherwise known as information channel) used by the tourists. He argued that until now the tourists are yet to clearly show how they obtained their tourism information and how the information is being distributed. They noted that this is a huge misconception which needed to be addressed by the researchers. Accordingly, it is also noted that tourists particularly the Arab tourists are yet to clear differentiate between the various methods or channels they used in sourcing for tourism information. For instance, the tourists have problem of differentiating between travel agents and primary source providers or between face-to-face and communication and internet channel of information. Grønflaten (2009) noted that a clear understanding between travel agents and primary source providers or between face-to-face and communication and internet channel of information would help us to understanding the Arab tourism search behavior. Based on this description, the information theory becomes very relevant in underpin this study as it stresses on the need for better sources of information and channels of information. It posits that individual in this case, the Arab tourists will obtain better information if their information search is based on right sources and channels of information.

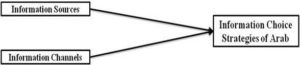

Based on the literature review as well as conceptual framework in figure 1, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1: there is a significant relationship between information source and information choice strategy.

H2: there is a significant relationship between information channels and information choice strategy.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework

Research Design

While this study acknowledged that several other research approaches exist, the study opts for a quantitative research approach. It is concerned with a quantitative data and then applies statistical analysis in the analysis of the data being collected (Saidu, 2006). Amin and Khan (2009) and Khurshid (2008) affirmed that quantitative questionnaire approach is suitable in conducting a research in social science research.

Population, Sampling and Unit of Analysis

The population of this study includes all the Arab Tourists coming to Malaysia. Currently, there are covers Arab coming to Malaysia in 2005, 200,000 population (Mat et al., 2009).This study adopts a convenient sampling approach of non-probability sampling technique. This sampling technique gives the researcher the opportunity to obtain participants or units that are most conveniently available for the study (Zikmund et al., 2013).One major reason for choosing convenience sampling technique in study is the lack of a proper sampling frame (Abzakh et al., 2013). The sample size for this study is 385 after the treatment of outliers and normality. Furthermore, the unit of the analysis is individual level. It includes all the individual Arab tourists coming to Malaysia. It is better to utilize them as they are the ones involved in tourism pleasure or adventure. Thus, utilizing them gave a better understanding of the issue under investigation. Indeed, there were the most suitable persons to provide information on the variables under investigation. Besides, past studies by Raitz and Dakhil (1989) and Grønflaten (2009) on tourism and pleasure tourists, used individuals such as the tourists and visitors to gathered information in a study of this nature. For the variable measurement, all constructs in this study were measured using a five-point likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) based on the previous work by Cavana et al., (2001). For the information source was measured using the following dimensions; travel agents, service providers, information center, journalists/ writers, other travelers, and friends/ family adapted from the work by Grønflaten (2005).Concerning the information channels variable, it was measured using five dimensions consisting of face-to-face, telephone, TV, print, and the Internet and it were adapted from the work by Grønflaten (2005). Also, personal characteristic was equally measured using the items adapted from Grønflaten (2005; 2009). Lastly, the information choice strategy was measured using the instruments adapted from the work by Grønflaten (2005).

Data Collection Procedure

This study adopts a well-structured questionnaire approach to gathered information from the respondents (Sekaran and Bougie, 2009); therefore, a self-administered questionnaire procedure also called drop-off and pick procedure was employed in distributing and retrieving the questionnaires from the respondents (Sekaran and Bougie, 2009).

Descriptive Analysis Result

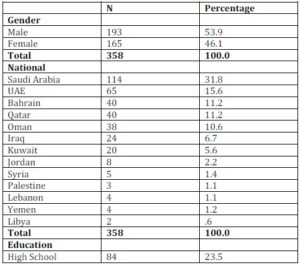

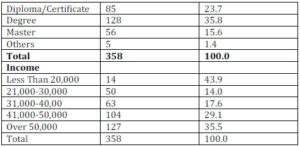

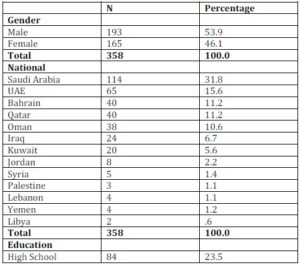

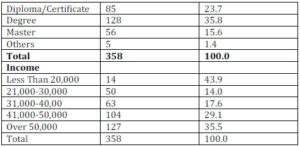

Table 2 presents the demographic information about the gender, nationality, education, and income of the respondents who participated in the study. Table 2 shows that slightly half of the respondents are male (53.9%), while the remaining half is female (46.1%). For the education, the result shows that majority of them have degrees (35.8%), high school (23.5%), diploma (23.7%), masters (15.6%) and others (1.4%). Similarly, the result shows that majority of them are in the income bracket of less than RM 20,000 (35.5%) percent earn income above RM 50,000 and (29.1%) of them earn income between RM 41,000 and RM 50,000 and the remaining earn between RM 21,000 and RM 30,000 (14%), and RM 31,000 and RM 40,000 (17.6%) respectively. For nationality, the result indicates that majority are from Saudi Arabia (31.8%), UAE (15.6%), Bahrain and Qatar (11.2%) respectively, Oman (10.6%), Iraq (6.7%), Kuwait (5.6%), and Jordan (2.2%) while other nationalities are just slightly greater than (1%).

Table 2: Descriptive Analysis of the Demographic

PLS Estimation Results with smartPLS

Due to conditions of insufficient, small sample size, explanation on endogenous construct, variance-based methods and the violation of the basic assumptions, the use of Partial Least Square (PLS) becomes necessary in this study in analyzing the data (Zhang, 2009). Sharma and Kim (2012) noted that the use of PLS becomes necessary under conditions of insufficient sample size while Chin (1998) concurred that PLS is required for data analysis in a situation where there are many indicators and factors are involved. In this vein, Zhang (2009) noted that PLS can deal with both formative and reflective construct, which is the exact situation in this study. Thus, these situations reflect the present study and therefore, the study opted for the use of PLS for the data analysis.

Measurement Model

For the model measurement, construct validity was conducted using the smartPLS with a two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) approach by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). Based on this, the internal reliability and convergent validity for constructs were first conducted and then followed by the assessment of the discriminant validity of constructs as indicated in Tables 3 and 4 respectively. For this, a minimum loading of 0.7 and above value was required for an item to be accepted for cross loadings and composite reliability as suggested Hair et al., (2011).

The result in table 3 as well as model 1 indicate that only 3 items Q4B and Q5B were retained for information channels construct; only 3 items coded Q12B, Q12E and Q13D were also retained for the information choice construct while 2 items coded Q1F and Q2F were equally retained for information source construct. Other items were deleted for due to low loadings of less than 0.70. For the average variance extracted (AVE), a minimum value of 0.5 is considered accepted (Bagozzi et al., 1991, Chin, 1998, Fornell and Larcker, 1981, Gefen and Straub, 2000) while the discriminant validity of constructs is determined by the average variance shared between each construct and its measures should exceed the variance shared between the construct and other constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Table 3 further indicates that all constructs utilized in the study produced AVE values more than the suggested value of 0.5 by (Bagozzi et al., 1991) and (Chin, 1998). Accordingly, the result also indicates that all constructs yielded factor loading more than 0.7 as suggested by (Hair et al., 2011) the values for composite reliability also indicated 0.7 and above as suggested (Gefen and Straub, 2000, Bagozzi et al., 1991), suggesting that the measurement model has achieved satisfactory internal reliability and convergent validity.

Table 3: Measurement Model Result

Note: A Composite Reliability (CR) = (square of the summation of the factor loadings)/[(square of the summation of the factor loadings) + (square of the summation of the error variances)];bAverageVariance Extracted (AVE) = (summation of the square of the factor loadings)/[(summation of the square of the factor loadings) + (summation of the error variances)].

Table 3 shows the result of the discriminant validity for the all the theoretical constructs. It indicates that the correlation for each construct is less than the square root of the average variance extracted suggesting that the measurement model has achieved adequate discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981, Hair et al., 2011). Similarly, Table 4 also revealed the discriminant validity result for the dimensions of economic downturn construct. For this, we first conducted a component factor analysis to determine and identify which dimension an item belongs to. In other words, the analysis was used to structure the measurement item according to the dimension they measured. The component factor analysis result is depicted in table. After this, we determined the discriminant validity of the dimensional constructs and the result indicates that the correlation for each dimensional constructs is less than the square root of the average variance extracted suggesting that the measurement model has achieved adequate discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981, Hair et al., 2011).

Figure 2: Loading Factors

Table 4: Discriminant Validity of Constructs

Note: Diagonals (bold face) represent the square root of the average variance extracted while the other entries represent the correlations.

Structural Model

The result of the Smartpls structural model depicted in Table 5 demonstrates that the relationship between the exogenous and the endogenous constructs of this study. For hypothesis H1, the result shows that information source is significantly related to information choice of the Arab tourists in Malaysia (ß = 0.26; p = 0.05). Furthermore, the result for the hypothesis H2 indicates that information channels significantly influence information choice of the Arab tourists in Malaysia (ß = 0.35; p = 0.05). The final result also indicates an R2 of 0.217017 which implies that the exogenous variables information source and information channels were able to explained 22 per cent of the variance of the endogenous construct-information choice strategy.

Table 5: Path Coefficients and Hypotheses Testing

Figure 3: The Influence of Both Information Source and Information Channels on the Information Choice Strategy.

Discussions, Implications and Conclusions

The major purpose of this study is to re-investigate the influence of both information source and information channels on the information choice strategy of the Arab tourists in Malaysia. In other words, the study investigates the relationship between information source, information channels and information choice of the Arab tourists in Malaysia. As a result, two major hypotheses were generated which are: (1) there is a significant relationship between information source and information choice strategy; (2) there is a significant relationship between information channels and information choice strategy. The hypotheses were tested using the smartpls as against the use of SPSS by the previous studies (Grønflaten, 2008; 2009).

Overall, the findings demonstrate that both information source and information channels significantly influence information choice strategy of the Arab tourists. The finding shows that information source is significantly related to information choice strategy. Hence, hypothesis 1 is supported. This finding supports the previous finding by Grønflaten (2009) who affirmed that information source is positively related to information choice strategy. The result suggests that an effective information source would help the Arab tourists to determine best information choice for their tourism adventure. It further implies that the level of information choice of the Arab tourists is determined by the information source available to them.

Furthermore, the finding demonstrates that information channel is significantly related with information choice strategy of the tourists. Hence, the finding supports the second hypothesis that information channels influence the information choice strategy. The finding is consistent with previous studies by Grønflaten (2009) who found that information search strategies, which comprise of information source and information channels, affect traveler information choice strategy. The findings suggest that information channels determine the level of information choice strategy of the tourism travelers. Thus, information channels are significant predictors of information choice strategy.

Therefore, based on the results from the regression analyses, the study concludes that both information source and information channels are indispensable factors for traveler’s information choice, as they significantly showed that predict information choice strategy. For the limitation of this study, the data utilized in this study only reflect the Arab tourists or pleasure travelers coming to Malaysia without taking into consideration other tourists from other countries and continents. Therefore, future inquiry into this topic is encouraged to use a larger more diversified sample from different economic and cultural regions for the purpose of enhancing the generalization of the findings of this study. Besides, qualitative study with a qualitative data is equally encouraged to provide more insight on this topic.

For the implications of this study, first it provides several insights that could contribute to the information development in the tourism industry as well as in the academic field of tourism management. Second, the knowledge about which factor influences the information choice strategy of the Arab tourism is very vital to the adequate understanding of how best to improve the tourism industry in Malaysia for a better tourism experience of the Arab tourists coming to Malaysia.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Abd Aziz, N. & Ariffin, A. A. (2009). “Identifying the Relationship between Travel Motivation and Lifestyles among Malaysian Pleasure Tourists and its Marketing Implications,” International Journal of Marketing Studies, 1, P96.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Abzakh, A. A., Ling, K. C. & Alkilani, K. (2013). “The Impact of Perceived Risks on the Consumer Resistance towards Generic Drugs in the Malaysia Pharmaceutical Industry,” International Journal of Business and Management, 8, p42.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Amin, H. U. & Khan, A. R. (2009). “Acquiring Knowledge for Evaluation of Teachers Performance in Higher Education Using a Questionnaire,” arXiv preprint arXiv:0906.4663.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Anderson, J. C. & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). “Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach,” Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y. & Singh, S. (1991). “On the Use of Structural Equation Models in Experimental Designs: Two Extensions,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, 8, 125-140.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Case, D. O. (2012). Looking for Information: A Survey of Research on Information Seeking, Needs, and Behavior, Emerald Group Pub Limited.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Cavana, R., Delahaye, B. L. & Sekaran, U. S. (2001). “Applied Business Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods,”

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Chin, W. W. (1998). “The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling,”

Publisher

9.Fodness, D. & Murray, B. (1997). “Tourist Information Search,” Annals of Tourism Research, 24, 503-523.

Publisher – Google Scholar

10.Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. (1981). “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error,” Journal of Marketing Research, 39-50.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Gefen, D. & Straub, D. W. (2000). “The Relative Importance of Perceived Ease of Use in IS Adoption: A Study of E-Commerce Adoption,” Journal of Association for Information Systems, 1, 0-.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Gitelson, R. J. & Crompton, J. L. (1983). “The Planning Horizons and Sources of Information Used by Pleasure Vacationers,” Journal of Travel Research, 21, 2-7.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Grønflaten, ø. (2005). “Sources and Channels of Tourism Information,” Griffith University.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Grønflaten, ø. (2008). “Predicting Travelers’ Choice of Information Sources and Information Channels,” Journal of Travel Research, 48, 230-244.

Publisher – Google Scholar

15.Grønflaten, ø. (2009). “The Tourist Information Matrix–Differentiating Between Sources and Channels in the Assessment of Travellers’ Information Search,” Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9, 39-64.

Publisher – Google Scholar

16.Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. (2011). “PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet,” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19, 139-152.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Hamilton, J. M. & Lau, M. A. (2005). “The Role of Climate Information in Tourist Destination Choice Decision Making,” Tourism and Global Environmental Change: Ecological, Economic, Social and Political Interrelationships, 229.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Jansen, B. J. & Rieh, S. Y. (2010). “The Seventeen Theoretical Constructs of Information Searching and Information Retrieval,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61, 1517-1534.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Khurshid, K. (2008). “A Study of the Relationship between the Professional Qualifications of the Teachers and Academic Performance of Their Students at Secondary School Level,” Proceedings of World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 2008. Citeseer.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Mat, A. B. C., Zakaria, H. A. B. & Jusoff, K. (2009). “The Importance of Arabic Language in Malaysian Tourism Industry: Trends during 1999-2004,” Canadian Social Science, 5, 12-17.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Raitz, K. & Dakhil, M. (1989). “A Note about Information Sources for Preferred Recreational Environments,” Journal of Travel Research, 27, 45-49.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Rogers, E. M. (1986). Communication Technology, Free Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Saidu, N. (2006). ‘Fundamental of Research,’ Ikeja, Lagos: Sanbio-Nes.

- Salman, A. & Hasim, M. S. (2012). “Factors and Competitiveness of Malaysia as a Tourist Destination: A Study of Outbound Middle East Tourists,” Asian Social Science, 8, p48.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Sekaran & Bougie (2009). ‘Research Methods for Business,’ Singapore: John Wiley & Sons Australian Ltd.

- Sharma, P. N. & Kim, K. H. (2012). “A Comparison of PLS and ML Bootstrapping Techniques in SEM: A Monte Carlo Study,” 7th International Conference on Partial Least Squares and Related Methods, Houston, TX, 2012.

Publisher

27.Tan, W. D. & Arnott, D. R. (1999). “Managerial Information Acquisition and the World Wide Web: A Theoretical Background,” 1999. 20-23.

Publisher – Google Scholar

28.Zhang, Y. (2009). “A Study of Corporate Reputation’s Influence on Customer Loyalty Based on PLS-SEM Model,” International Business Research, 2, P28.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Zikmund, W., Babin, B., Carr, J. & Dan Griffin, M. (2013). Business Research Methods, South_Western Cengage learning, United States.

Publisher – Google Scholar