Introduction

Analysis of relationships between manufacturers and retailers has often been centred on minimising costs and managing conflicts. The channels are considered independent where each player seeks to reach their objectives and achieve profits at the expense of the other. However, with mutations and changes of the environment and with the emergence of relational marketing during the 90s, it became imminent to reconsider relationships between producers and retailers and to opt for collaboration and partnership, in terms of long-term, value-creating and mutually-beneficial relationships. These relationships offer the different players an opportunity to create strategies and reach important performances (Frazier et al., 2009).

Relational orientation, mainly within distribution channels (DC), remains a domain relatively less explored, the examination of which raises some controversies (Lepers, 2003). Review of literature shows an absence of a concise definition of relational orientation within distribution channels and lack of a measurement scale to apprehend the construct (Frazier, 1999).

Our aim is to propose a definition and a measurement scale of relational orientation within distribution channels. In this paper, we track the evolution of the analysis of exchanges within distribution channels, then we discuss dimensionality of relational orientation and its specific dimensions impeding on relationships between channels. After presenting the adopted methodology, we report the results of the qualitative study and the exploratory quantitative study.

Then, we propose our definition of relational orientation within distribution channels and we finish with a conclusion which includes some implications and future research.

Evolution of the Nature of Exchanges within Distribution Channels

Reviewing research focusing on studying exchanges within distribution channels shows an evolution of the analytical framework and disagreement in the perspectives studying these systems. First, it is from an economic perspective that exchanges between channels are studied. Economic proposals point to minimising costs as a way of coordinating between middlemen and to seeking selfish interests through opportunistic behaviour (Willamson, 1985). Transactions and players are considered independent from each other and the relationship ends once the transaction ends. However, this line of thinking seems to be restrictive (Jeanmougin, 1992). They adopt a short-term transaction of exchanges and ignore the social and relational dimensions.

Moreover, the social approach came to uphold the limitations of the classic economics schools by considering distribution channels as a social system governed by psychological and behavioural aspects (Robicheaux and El Ansary, 1975; Stern and El Ansary, 1972). Behaviourist models essentially focused on two behavioural variables, power and conflict, as basic concepts for the study of exchanges within DC (Gaski, 1984; Gaski and Nevin, 1985; Anderson and Narus, 1990; Skinner et al., 1992). Nevertheless, the temporary version of these models remains limited in time. Channels are considered competitors and there is no research devoted to examining development of relationships in time.

With the integrative paradigm, the politico-economic model of Stern and Reve (1980), there is the joint consideration of the economic and sociological impulses. This paradigm offers a foundation for comprehending construction, development, maintenance and advancement in time inter-organisational relationships (Arndt, 1983). It reveals aspects of the relationships dynamics between one another within the DC and stands as the foundation of inter-firm relational approach and sets the transition from transactional marketing to relational marketing.

The 90s decade, with its environmental mutations, witnessed the emergence of the paradigm of relational marketing which focused on establishing and maintaining long-term relationships and which reconsidered the nature of inter-firms exchanges by distinguishing transactional exchanges from relational exchanges as proposed by Macneil’s theory of relational contract (1980, 1983).

Indeed, with relational marketing, exchanges are considered a succession to independent transactions deprived from any social dimensions. There is independence between intervening parties, its end is planned and is integrated within a line of thinking based on confrontations between players (Bagozzi, 1975; Dwyer et al., 1987; MacNeil, 1980; Heide, 1994). However, in relational marketing, exchanges represent a set of inter-related repeated transactions. It is considered a continuous temporary process (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Wilson, 1995). Moreover, exchanges go beyond its intrinsic nature to reach a social dimension (Arndt, 1983; Dwyer et al., 1987). Exchanges are assimilated for a relationship where partners communicate more information, engage in complex and durable social relationships and where relationships are customized, based on cooperation, and tarnished with a win-win situation (Guibert, 1996; Dwyer et al., 1987; Weitz and Jap, 1995; N’goala, 1998, Lin et al., 2008).

Relational Orientation within Distribution Channels

Marketing literature on relational orientation in different context points to a disagreement on definitions, dimensions and measurement variables adopted by these authors (Daigle and Ricard, 2000; Yau et al., 2000; Izquierdo and Cliian, 2004; Prim and Sabadie, 2005; Gordon et al., 1997). Moreover, review of the literature shows an absence of a clear and concise definition of relational orientation within distribution channels which takes into account the specificities of the relationships between channels and identifies its specific dimensions (Frazier, 1999).

Relational Orientation: A Multidimensional Concept

All authors agree on multi-dimensionality of relational orientation and they admit that it is careless, even risky to consider it a one-dimensional concept (Perrien and Ricard, 1996).

Review of the literature reveals that comprehension of the relational process needs considering and compromising between economic and social elements. Social aspects in a relationship play a role in forming and maintaining tight and close relationships (Ganesan ,1994), whereas economic elements reflect the profits to be generated from these relationships (Izquierdo and Cliian, 2004; Heide, 1994). In addition to these two aspects, it is imperative to consider well time horizon since future exchanges and past events are important to relational exchanges (Dwyer et al., 1987; Macneil, 1980 ; Ganesan, 1994).

Then, three dimensions seem to be important and necessary to understand relational orientation. These are:

- Time dimension: it implies the relationship projection into time and its continuity in the long-term.

- The social or affective dimension: it shows the desire to maintain the relationship.

- The economic or functional dimension: it reflects the usefulness of and interest in the relationship where there is a need for its continuity.

Then, it can be hypothesized that:

What are the distinctive dimensions of relational orientation within distribution channels?

Dimensions of Relational Orientation within Distribution Channels:

A review of the literature on distribution channels has allowed for generating variables characterizing relationships between channels. These are: commitment (Gundlach et al., 1995; Narayandas and Rangan, 2004; Kim and Frazier, 1996) and dependence (Kumar et al., 1995, Bonet and Dannad, 2007; Abbad, 2007; Kalawani and Narayandas, 1995).

Commitment: The Corner Stone of Durable Relationships

Importance of commitment in developing tight and durable relationships is unanimous. It is at the heart of explaining customers-suppliers relationships, mainly between distribution channels (Kumar et al., 1995; Ganesan et al., 2010). Commitment is an attitude oriented to the long-term and is essential to successful long-term relationships. It is as well a concept central to transition from a transactional approach to a relational approach (Gundlach et al., 1995; Ganesan et al., 2010; Morgan and Hunt, 1984; Wilson, 1995).

Marketing literature identifies three components of commitment (Geyskens et al., 1996; Kumar et al., 1995; Anderson and Wietz, 1992):

- The attitudinal component: it is an affective aspect of commitment which reflects willingness to maintain the relationship with a partner because of fascination or affection.

- The temporal component: it reflects intention to lengthen the relationship and maintain it in the future.

- The instrumental component: it is an aspect which denotes an interest in maintaining the relationship because of the allocated resources difficult to redeploy in another relationship.

Commitment is the corner stone of the explanation, existence and development of customers-suppliers relationships. It can be conclude then that:

Dependence: The Functional Dimension of Relational Orientation

Dependence is a variable characterizing the relationship between producers and retailers and is a predictive and discriminate variable of exchange relationships (Kumar et al., 1995; Buchanan, 1992; Gundlach et Cadotte, 1994). Dependence is defined as the need to maintain an exchange relationship to reach the desired objectives (Frazier, 1983). It indicates the degree of difficulty that a company may meet to replace a partner and represents the economic quality of the relationship (Heide and John, 1990; Barnes et al. 2010; Ganesan, 1994; Lush and Brown, 1996).

So, it can be deduced that:

Methodology

The used methodology is divided into two phases. First, a qualitative research is conducted to identify the distinctive components of relational orientation within distribution channels. This study is followed by an exploratory quantitative study which would allow for checking the dimensionality and reliability of the proposed measurement scale.

The Exploratory Qualitative Study: Data Collection and Results

The aim of this qualitative study is to better understand relational orientation within producers-supermarkets relationships and determine its dimension. Individual semi-directed interviews on 11 industries and 7 retail managers in Tunisia are conducted. Structured interviews with predetermined topics issued from the literature were designed.

Analysis of the interviewees’ discourse brings light to relational orientation within producers-supermarkets relationships and to the specificities of relational-oriented relationships. The protagonists consider these relationships durable that answer an extended temporal perspective. There is willingness to invest in this type of relationship and the intention to develop and maintain it.

Furthermore, the interviewed insist on the importance of these relationships. Their value is perceived as high and the need to maintain them is important. This importance is linked to the contribution of this relationship to the company’s turnover, to the inability to replace a partner and to the difficulty of developing other alternatives.

Additionally, professionals maintain that these exchanges report to personal, friendly and warm relationships. Generally, the two partners find pleasure to work together. They mutually appreciate each other and attraction is developed.

The qualitative analysis allowed to show that relational orientation within distribution channels includes (1) a long-term orientation, (2) an attraction between partners and (3) usefulness of relationship. Then, it can be concluded that dimensions of relational orientation within distribution channels are: temporal commitment, affective commitment and dependence.

The Quantitative Exploratory Study: Instruments and Measures Adopted

To test dimensionality of relational orientation within distribution channels and propose a measurement scale for its operationalisation, a questionnaire survey is conducted. Sources of the data used were producers of massively-consumed products in Tunisia and suppliers of supermarkets. A purposive sampling method (Lambin et al. 1994) and the method of key informant (Heide and John, 1990) were adopted for the study.

Moreover, to measure the variables temporal commitment, affective commitment and dependence, we refer to the literature and existing tested scales with an α > à 0.7 (Table 1). A Likert 5-point scale was opted for.

Table1: Measurements Scales of Relational Orientation Dimensions

Finally, 104 companies spreading across the Tunisian territory replied to the questionnaire.

Testing Dimensionality and Reliability of Relational Orientation Scale

Dimensionality of relational orientation scale is evaluated by a principal component analysis (PCA) and its internal coherence is estimated by Cronbach’s alpha.

The SPSS-derived results show that items of the scale have significant common variance,

correlation matrix reports coefficients largely superior to 0,5, the sphericity test reports significant Chi-squares at 0.001 and KMO test is equal to 0,811. Then, using a factorial analysis to test the scale is possible.

The PCA generates a 3-factor structure explaining 71,494% of explained variance. Varimax rotations have been conducted as the results showed that the items were correlated. After a first rotation, factorial contribution of AENGP1 item is found to significantly scatter across several factors. This item was deleted. Using Kaiser’s criterion, the results of a new PCA conducted on the 9 items point to 3-factor structure, explaining 73% of explained variance.

Nevertheless, the results of the second PCA reveal that the items DEPP1, AENGP2 and AENGP3 are significantly correlated with the first two factors. Then, a third Varimax rotation was carried out. The results indicate a 3-factor structure.

- The first factor explains 26,484 % of explained variance. It relates to dependence and represents the functional dimension of relational orientation.

- The second factor explains 25,745 % of explained variance. It relates to temporal commitment and represents the temporal dimension of relational orientation.

- The third factor explains 20,766 % of explained variance. It relates to affective commitment and represents the affective dimension of relational orientation.

Additionally, internal coherence of relational orientation measurement scale allows for accepting the 9-item construct as standardised Cronbach’s alpha is 0,8214 and elimination of one of the items does not improve the scale’s internal coherence.

- A definition of relational orientation within distribution channels

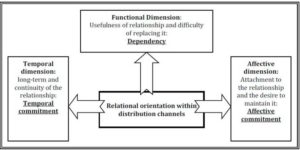

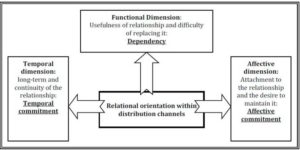

Referring to the literature review, the qualitative study and the exploratory quantitative study, the conclusion can be that relational orientation is a three-dimension concept whose dimensions are (Figure 1):

- A temporal dimension which reflects the long-term and continuity of the relationship and which is apprehended by temporal commitment.

- An affective dimension which corresponds to an attachment to the relationship that the desire lengthen and which is reflected in affective commitment

- A functional dimension which indicates the usefulness of the relationship and the need to maintain it, given its economic importance and it is reflected in dependence.

Figure 1: Dimension of Relational Orientation within Distribution Channels

Then, the following definition of relational orientation within distribution channels which takes into account the specificities of the relationships between channels is proposed:

Contributions and Future Research

The contribution of this research is three fold: theoretical, methodological and empirical. This paper contributes to enriching research in relational marketing by proposing a definition of relational orientation within distribution channels which takes into account the specificities of the relationships between channels. This definition highlights the three distinctive dimensions of relational orientation which are the functional, temporal and affective dimensions.

This work proposes a 9-item measurement scale to operationalise relational orientation within distribution channels. The exploratory quantitative study shows that the dimensions of relational orientation within distribution channels are dependence, affective commitment and temporal commitment. This scale has a good internal coherence.

From a managerial point of view, this study provides managers with criteria to segment relationships, i.e. relational orientation. Distribution channels retain important relationships portfolios; each with different specificities. Segmenting relationships to identify a relationships typology using relational orientation allows managers to adopt a management mode appropriate to each type of relationship and identify the adequate marketing interventions and relational strategies.

A second quantitative phase is scheduled to test the convergent, discriminant and predictive validity of the proposed scale. A confirmatory analysis, using structural equation modelling, will be conducted.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Abbad, H. (2007). ‘Les Relations Entre La Grande Distribution et Les PME Agroalimentaires: Quels Déterminants de l’orientation à Long Terme des Relations,’ 1ère Journée de Recherche Relations entre Industries et Grande distribution Alimentaire, Avignon.

Anderson, E. & Weitz, B. (1992). “The Use of Pledges to Build and Sustain Commitment in Distribution Channels,” Journal of Marketing Researc, 29 (1), 18-34.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Anderson, J. C. & Narus, J. A. (1990). “A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships,” Journal of Marketing, 54 (1), 42-58.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Arndt, J. (1983). “The Political Economy Paradigm: Foundation for Theory Building in Marketing,” Journal of Marketing, 47, 44-54.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Bagozzi, R. P. (1975). “Marketing as Exchange,” Journal of Marketing, 39, 32-39.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Barnes, B. R., Leonidou, L. C., Siu, N. Y. M. & Leonidou, C. N. (2010). “Opportunism as the Inhibiting Trigger for Developing Long-Term-Oriented Western Exporter–Hong Kong Importer Relationships,” Journal of International Marketing, 18:2, 35-63.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Bonet, D. B. & Danand, C. (2007). “Relations Industrie-Commerce: Le Déréférencement au Regard du Marketing et de la Jurisprudence,” CRET-LOG session 8. 42 – 56.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Buchanan, L. (1992). “Vertical Trade Relationships: The Role of Dependence and. Symmetry in Attaining Organizational Goals,” Journal of Marketing Research, 29(1), 65-75.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Daigle, A. & Ricard, L. (2000). “L’approche Relationnelle dans le Secteur Hôtelier : Une Étude Exploratoire,” Actes de conférence, l’Association Française du Marketing (AFM), Montréal, 1125-1134.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H. & Oh, S. (1987). “Developing Buyer-Seller Relationship,” Journal of Marketing, 51, 11-27.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Frazier, G. L. (1983). “On the Measurement of Interfirm Power in Channel of Distribution,” Journal of Marketing Research, 20, 158-166.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Frazier, G. L. (1999). “Organizing and Managing Channels of Distribution,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2), 226-240.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Frazier, G. L., Maltz, E., Antia, K. D. & Rindfleisch, A. (2009). “Distributor Sharing of Strategic Information with Suppliers,” Journal of Marketing, 73(4), 31-43.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ganesan, S. (1994). “Determinants of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships,” Journal of Marketing, 58, 1-19.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Ganesan, S., Brown, S. P., Mariadoss, B. J. &. Ho, H. D. (2010). “Buffering and Amplifying Effects of Relationship Commitment in Business-to-Business Relationships,” Journal of Marketing Research, 47(2), 361-373.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gaski, J. F. (1984). “The Theory of Power and Conflict in Channels of Distribution,” Journal of Marketing, 48(3), 9-29.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gaski, J. F. & Nevin, J. R. (1985). “The Differential Effects of Exercised and Unexercised Power: Sources in a Marketing Channel,” Journal of Marketing Research, 22, 130-142.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J.- B. E. M., Scheer, L. K. & Kumar, N. (1996). “The Effects of Trust and Interdependence On Relationship Commitment: A Trans-Atlantic Study,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13, 303-317.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Gordon, M. E., Kim, M. & Mark, F. (1997). ‘Relationship Marketing in Channel Relationships: The Role of Involvement,’ in Enhancing Knowledge Development in Marketing (Volume 8), William M. Pride and G. Thomas M. Hult eds, American Marketing Association, pp253-258.

Guibert, N., Dubois, P.- L. & Dupuy, Y. (1996). “La Relation Client-Fournisseur et les Nouvelles Technologies de l’information: Le Rôle des Concepts de Confiance et de l’engagement,” thèse de doctorat en sciences de gestion, Université de Montpellier 2.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gundlach, G. T., Achrol, R. S. & Mentzer, J. T. (1995). “The Structure of Commitment in Exchange,” Journal of Marketing, 59: 1, 78-88.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Gundlach, G. T. & Cadotte, E. R. (1994). “Exchange Interdependence and Interfirm Interaction: Research in a Simulated Channel Setting,” Journal of Marketing Research, 31, 516-532.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Heide, J. B. (1994). “Interorganizational Governance in Marketing Channels,” Journal of Marketing, 58, 71-85.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Heide, J. B. & John, G. (1992). “Do Norms Matter in Marketing Relationships?,” Journal of Marketing, 56, 32- 44.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Izquierdo, C. C. & Cillán, J. G. (2004). “The Interaction of Dependence and Trust in Long-Term Industrial Relationships,” European Journal of Marketing, 38(8), 974 – 994.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Jap, S. D. & Ganesan, S. (2000). “Control Mechanisms and the Relationship Life Cycle: Implication for Safeguarding Specific Investments and Developing Commitment,” Journal of Marketing Research, 37, 227–245.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Jeanmougin, C. (1992). ‘L’évolution de la Fonction de Gros,’ Revue Française de Gestion, 90, 85-103.

Kalawani, M. U. & Narayandas, N. (1995). “Long-term Manufacturer-Supplier Relationships: Do they Pay Off for Supplier Firms?,” Journal of Marketing, 59, 1-16.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Kim, K. & Frazier, G. L. (1996). “A Typology of Distribution Channel Systems: A Contextual Approach,” International Marketing Review, 13(1), 19-32.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Kumar, N., Scheer, L. K. & Steenkamp, J.- B. E. M. (1995). “The Effects of Perceived Interdependence on Dealer Attitudes,” Journal of Marketing Research, 32, 348-356.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Lambin, J. J. (1994). ‘La Recherche Marketing : Analyser, Mesurer, Prévoir,’ Ediscience International.

Google Scholar

Lepers, X. (2003). “Vers une Nouvelle Conceptualisation de la Relation d’échange Fournisseurs – Grands Distributeurs,” Conférence de l’Association Internationale de Management Stratégique Les Côtes de Carthage.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lin, Y., Tao, L., Li, Y. & El Ansary, A. I. (2008). “The Impact of Distributor’s Trust in a Supplier and Use of Control Mechanism on Relational Value Creation in Marketing Channels,” Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing,. 23(1), 12-22.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Lusch, R. F. & Brown, J. R. (1996). “Interdependency, Contracting, and Relational Behaviour in Marketing Channels,” Journal of Marketing, 60, 19-38.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Macneil, I. R. (1980). The New Social Contract: An Inquiry into Modern Contractual Relations, New Haven, CT.: Yale University Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Macneil, I. R. (1983). “Values in Contract: Internal and External,” Northwestern university law review, 78(2), 340 – 419.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Morgan, R. M. & Hunt, S. D. (1994). “The Commitment – Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing,” Journal of Marketing. 58, 20-38.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

N’goala, G. (1998). ‘Epistémologie et Théorie du Marketing Relationnel,’ Actes du 14ème Congrès de l’Association Française du Marketing, Bordeaux.

Google Scholar

Narayandas, D. & Rangan, V. K. (2004). “Building and Sustaining Buyer-Seller Relationships in Mature Industrial Market,” Journal of Marketing, 68, 63-77.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Perrien, J. & Ricard, L. (1996). Les Facteurs Explicatifs et Normatifs d’une Approche Relationnelle: La Perception Des Clients Organisationnels,’ 12ème Congrès organisé par l’AFM.

Google Scholar

Sabadie, W. & Prim-allaz, I. (2005). “Orientation Relationnelle Sociale et Autonomie: Facteurs Explicatifs du Choix des Modes de Contact,” 1ères Recherche en Marketing IRISJournées de IAE de Lyon.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Robicheaux , R. A. & El Ansary, A. (1975). ‘A General Model for Understanding Channel Member Behaviour,’ Journal of Retailing, 52(4), 13- 30.

Skinner, S. J., Gassenheimer, J. B. & Kelley, S. W. (1992). “Cooperation in Supplier-Dealer Relations,” Journal of Retailing, 68(2), 174 – 193.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Stern, L. W. & El Ansary, A. (1972). ‘Power Measurement in the Distribution Channels,’ Journal of Marketing Research, 9, 254-262.

Stern, L. & Reve, T. (1980). “Distribution Channels as Political Economies: A Framework for Comparative Analysis,” Journal of Marketing, 44, 52-44.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Weitz, A. B. & Jap, D. S. (1995). “Relationship Marketing and Distribution Channels,” Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 305-320.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Williamson Oliver, E. (1985). “The Economic Institutions of Capitalism Firms, Market, Relational Contracting,” New York.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Wilson, D. T. (1995). “An Integrated Model of Buyer-Seller Relationship,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 335-345.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Yau, O. H. M., Mcfetridge, P. R., Chow, R. P. M, Lee, J. S. Y., Sin L. Y. M. & Tse, A. C. B. (2000). “Is Relationship Marketing for Everyone?,” European Journal of Marketing, 43(9/10), 1111- 1127.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct