Introduction

Prosperity is measured in terms of economic growth and this economic growth in turn has been associated with increasing energy use and climate changes in the past. Tackling global warming and the depletion of resources is one of the main concerns the world faces. Many developing countries like India and China are outperforming developed countries in many respects and new economic powerhouses are developing. The majority of patents however still originate in a few countries like Japan, the US and Germany. The new economy and shifting world requires innovation, new solutions and more responsible business practices in all countries around the globe especially in these newly developing countries (Blowfield and Murray, 2011, p. 5). As a consequence companies will have to participate in global networks, as responsible business practices do not work in isolation or a vacuum. They can be seen as “open systems” dependent on some actors and are influential to others (Berniak-Woźny, 2010, p. 273).

How open these systems are, needs to be questioned critically in developed countries where governments stepped in to save private sector companies from failure during the financial crisis in 2009. The example of bank’s behaviour before the financial crisis shows that company behaviour is often a cause for concern. Displaying more transparency about their business practices and responsible company behaviour in terms of environmental protection and key social challenges like poverty and inequality are becoming great opportunities (Blowfield and Murray, 2011, p. 5-6).

The concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CRS) originates from Bowen’s book “Social responsibilities of Businessman” in 1953 in which he asked the question: “What responsibilities to society can business people be reasonably expected to assume” (Berniak-Woźny, 2010, p. 272)? In the 50’s the focus of CSR was on the behaviour of companies and towards obeying the law. The academic debate in the next three decades focused on how firms can act responsibly. From the 90’s on the debate included environmental, legal, ethical and social concerns (Blowfield and Murray, 2011, p. 7).

CSR refers to “the obligation of a firm, beyond that required by law or economics, to pursue long-term goals that are good for society” (Robbins and De Cenzo, 2001). How successful a company’s CSR activities are depends firstly on the implementation and development of a holistic concept, which includes the consideration of all stakeholder perspectives on firm level (e.g. managers, shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, NGO’s and local governments). Secondly the success depends on numerous situational factors like the economical, social, cultural, and industrial factors (Berniak-Woźny, 2010, p. 275). CSR can thus be seen “as an umbrella term embracing theories and practices relating to how business manages its relationship with society” (Blowfield and Murray, 2011, p. 378).

CSR is increasingly becoming popular in developing countries in both, the academic world and among managers who put these theories into practice. Nevertheless, one common global model of CSR cannot be replicated by developing countries without prior consideration and analysis of the marcro-environmental conditions and country-specific determinants (Berniak – Woźny, 2010, p. 271-272).

CSR Approaches in Developed and Developing Countries

In a global study of 800 CEO’s, 93% see sustainability as important for their company’s future success. The reason for engaging in sustainability activities is the impact on a company’s brand, trust and reputation. In emerging markets, the impact on development gaps in business is the second most cited factor. 38% of CEO’s in the study reported that they contribute to local infrastructure and social development in their country (Lacy and Hayward, 2011, p. 348). The driving factors for CEO’s to take action on sustainability issues are brand, trust and reputation for developing countries (74%) and developed countries (72%). Especially personal motivation seems to influence CEO’s to take action in developed countries (44%) compared to 38% in developing countries. Furthermore, 43% of CEO’s in developed countries see potential for revenue growth and cost reduction compared to 33% in developing countries (Lacy and Hayward, 2011, p. 351).

Developing Countries

According to Berniak-Woźny (2010, p. 275), CSR campaigns in developing countries are distinct from CSR in developed countries because of their expanding economies and the social and economical impact of the financial crisis. CSR in developing countries tends to be less formalized and is usually done by large, high profile national and multinational companies. In developing countries, CSR tends to be issue-specific (e.g. fair trade, supply chain, HIV/AIDS) related to a specific industry sector (e.g. agriculture, textile, and mining). Lastly, CSR activities in developing countries often cover social services that would be seen as government’s responsibility in developed countries (Berniak-Woźny, 2010, p. 279). Securing clean water or fighting hunger are more often addressed by companies in developing countries (30%) than in developed countries (20%) (Lacy and Hayward, 2011, p. 351). In Lacy and Hayward’s (2011, p. 351) CEO study, 72% of the CEO’s in developing countries and 70% of the CEO’s in developed countries named education to be the most critical CSR issue to address for the success of the business. Climate change scored nearly as high as education. 56% mentioned poverty in developing countries, whereas 43% of the CEO’s listed poverty in developed countries (Lacy and Hayward, 2011, p. 351). Furthermore, the promotion of CSR activities seems to be a major weakness in developing countries. Over 50 percent of enterprises do not disclose information about their CSR activities (Berniak-Woźny, 2010, p. 279).

CSR activities in developing countries differ from CSR activities in developed countries for several reasons. First, the economies in developing countries are growing more rapidly and thus are a profitable opportunity for businesses. Especially foreign firms who tend to be short-term oriented in host countries might not act as responsible as in their home country. Second, social and environmental crises are more acutely felt in developing countries so that CSR activities are likely to have a different focus. Globalization, economic growth, investment, and business activity are likely to have the most dramatic social and environmental impact (both positive and negative). As a consequence, it can be concluded that developing countries experience different CSR challenges which are collectively quite different to those faced in the developed world (Berniak-Woźny, 2010, p. 275).

Former president Gaddafi, for example, used sustainability to engage in business relations with the Western world in 2007. He announced the construction of a zero-carbon eco-tourism resort in Libya. The resort was supposed to employ local labour, use local resources (energy and food) and operate with human working conditions. One month later Libya was elected onto the United Nations Security Council. Sustainability was used to re-enter the Western world and to buy into the primary export business. The example shows that sustainability is still a club dominated by Western interests and profit motive (Williams, 2008, p. 108).

A direct transfer of CSR models from developed countries may fail and slow down or even stop implementation of the concept in the rest of the world (Berniak-Woźny, p. 272). The problem however is that CSR research is still relatively underdeveloped in developing countries and tends to be ad hoc with a heavy reliance on convenience-based case studies or descriptive analysis (Berniak-Woźny, 2010, p. 277).

Consumer Motivation, Involvement and Culture

CSR Attitude: The MENA Region

The initial reason for a company to engage in CSR and corporate governance activities in the MENA region is to attract foreign investment and to develop the local capital markets (Koldertsova, 2010, p. 219). Especially countries with no petrochemical resources need money for developing their infrastructure and the financial sector in the region. In particular Egypt and Syria who have shifted towards a market-based economy need these investors. The MENA region has been very disclosure-averse in the past, meaning that shareholders have not been controlled and there has been a lack of transparency in the corporate sector. Very slowly the development in the capital markets require more transparency and pushed governance issues forward (Koldertsova, 2010, p. 219).

Since the events of 9/11 and after the stock market crash in 2006, the MENA region has recognised itself while being pressured from international agencies, to implement the global standards of good public governance (Mehanna et al. 2010, p. 118). Oman and Egypt were the first countries in the MENA region to implement domestic governance codes in 2002 and 2005 respectively which were based on the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. In the following years 11 corporate governance codes were introduced by national regulations between 2005 and 2009. Today only 3 countries (Kuwait, Libya and Iraq) out of the 17 countries surveyed (Algeria, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, Syria, Yemen, Palestinian National Authority, Libya and Iraq) do not have corporate governance codes and recommendations at least for banks and credit institutions (Koldertsova, 2010, p. 222). Over the years the reporting has moved from ad hoc responses to a systematic activity companies do regularly. But still today corporate reporting is greatly influenced by macro-environmental factors like the PESTL factors (political, economic, socio-cultural, technological and legal factors (Rizk et al., 2008, p. 306).

The MENA region is facing several challenges like oil, growth of the working age population, enrolment in secondary education, high reliance on fixed investments and presence of religion fractionalization Although the region is wealthy in oil, there is an income disparity between oil-rich Gulf countries and non-oil countries. Each of the 23 MENA countries faces its own particular challenges. In Yemen, the population of young people is very fast-growing, in Lebanon there is religious fractionalisation and a “weak economic, political, and judicial public governance” (Mehanna et al. 2019, p. 117-118).

A study of 60 Egyptian firms in nine different industries reveals that disclosure practices of CSR activities in the annual report differ. Industry membership is related to the type of disclosure. Employee information was found to be most important in industries where health and safety are of concern. The disclosure rates were 65% in the sample while the food and beverage industry, the cement industry, chemicals and ceramic industries had disclosure rates of 100%. Furthermore the results show that private organisations disclose more information than government-owned firms (Rizk et al. 2008, p. 317). Egyptian corporations still need a lot of time and effort until the CSR standards are compatible with Western societies, but there is pressure in the MENA region and on companies worldwide to become “more transparent, accountable, responsible and ultimately to help supply chains and economies to become more sustainable” (Rizk et al. 2008, p. 321).

Developed Countries

Sustainability and awareness of social and ecological issues is growing on importance in developed countries (Williams, 2008, p. 108). The financial crisis in 2007 has transformed the world economy into a deep recession in developed countries as well. This recession did not only have an impact on the world economy, but also on psychological, social, political, and ethical perspectives (Berniak-Woźny, 2010, p. 271).

In 2008, three quarters of all Fortune companies already had a CSR strategy and currently 4,000 companies worldwide are reporting on their CSR activities (KPMG, 2008, p. 4; European Commission, 2011a, p. 22). The European Commission (2011) defines CSR as “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with stakeholders on a voluntary basis”. This voluntary interaction is in fact practised in many forms. The activities range from grants, sponsorships and donations to technical specialisation and employee involvement (Kotler and Lee, 2005, p. 4). Companies have recognised that doing business in a sustainable and ethical way is an important means to fulfil the demanding attitude of ethical consumers and to achieve a competitive advantage in the long term (West et al., 2010, p. 446).

Consumers in developed countries are concerned about the environmental and social impact of their consumption choices and their attitude and behaviour in each stage of the consumption process is beginning to change. Many consumers make more altruistic and ecocentric consumption choices, especially in their key consumption contexts. They consider the effects a purchasing decision has on the environment and on the wider society rather than just paying attention to satisfying their own consumption needs (Belz et al., 2009, p. 82-84). Consequently, companies need to understand consumer motivations, concerns and barriers for choosing sustainable product alternatives.

Consumers are increasingly adopting a critical attitude when making their buying decisions and companies have become a subject of scrutiny (Sheikh and Beise-Zee, 2011). If a product does not correspond to these expectations, consumers are likely to boycott products or switch to other alternatives (Harrison et al., 2005, p. 2).

Lacy and Hayward (2011, p. 352) study shows that CEO’s expect to target different stakeholder groups. Companies particularly in developed countries have realised the importance of targeting consumers. 61% of the CEO’s in developed named consumers as the most important stakeholder group compared to 50% in developing countries. Employees scored very high as well with 50% and 36% in developed and developing countries respectively. A large difference in perception is also shown for communities. In developing countries 38% of the CEO’s listed communities, whereas only 21% did in developed countries (Lacy and Hayward, 2011, p. 352).

In a multinational survey of over 800 CEOs, 52% of the CEO’s in developed markets believe that sustainability will be “very important” and 40% state that it is “important” to the future success of their business (Lacy and Hayward, 2011, p. 350). These changing attitudes in turn have a strong influence on communication strategies in marketing (Harrison et al., 2005, p. 228). Because of this rising importance and growth of CSR activities, it is increasingly difficult for companies to effectively differentiate themselves through ordinary CSR initiatives.

Many companies publish CSR reports which showcase their CSR engagement to stakeholders. In 2005, 64% of the 250 largest multi-national corporations published CSR reports in which they display their CSR activities to their stakeholders either within their annual reports or as separate reports (Belz and Peattie, 2009, p. 35). Because most companies try to display their reasons for existence in terms of “service to society” rather than profits in these reports, these approaches of Corporate Social Reporting are often seen as “cosmetic” measures and have become less effective. For many companies, Corporate Social Reports are just another form of PR to improve the image of the company (Belz and Peattie, 2009, p. 35-36).

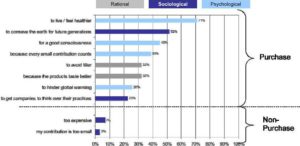

CSR Attitude: The Case of Germany

Germany has a long history in terms of environmental protectionism. German households have strict guidelines for e.g. litter separation. Over the last two decades a value shift has taken place on three levels: rational level, psychological level and sociological level (Belz et al. 2009, p. 82-84). On a rational level, consumers want to know the net benefit (perceived benefits- perceived cost) of a product they buy for any of the concerned stakeholders. The level of a consumer’s psychological explanation for the purchase also plays a role which is the consumer’s attitudes and willingness to engage with sustainability issues, his or her personal relevance in terms of social responsibility and the level of company trust towards the product he or she buys (Steffen, 2010). The third, sociological level the consumer considers for the purchasing decision evaluates how he thinks the consumption activities are perceived by others e.g. a solar collector on the roof top is visible to others and generally perceived positive whereas bio-eggs are invisible products neighbours won’t see or talk about.

Methodology and Sample

To investigate attitudes towards sustainable products and their shopping behaviour, 32 German consumers were accompanied on their shopping trips to the supermarket or discounter. The study included a Pre-Shopping Questionnaire surveying shopper values and questions about their shopping behaviour in the store. While in the store, their shopping behaviour was observed including the in-store the sections visited and a record of all functional and sustainable products looked at, touched and bought was kept. After the shopping trip, post-shopping questions about the consumer‘s motive for or against sustainable consumption, his store assessment, his consumption attitude and his socio-demographic data were asked.

The sample contained 21 females and 11 males. Mean age was 36 years and 59% of the sample lived in a one or two person household. 45% of the sample associated themselves with LOHAS (Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability) and 62.5% actually bought some form of sustainable product. Approximately half of the sample visited a full assortment retail store and the other half a discounter.

Results

The results show that sustainable buyers value social factors like family and friendships. Status does not seem to be important to them. Furthermore, there was a high concentration on psychological sustainable consumption motives (see Graph 1).

Graph 1: Motives for Buying Sustainable Products

Graph 1: Motives for Buying Sustainable Products

Consumers were most concerned about their consumption of sustainable products when evaluating product alternatives (e.g. in the choice between bio products vs. non-bio products). Sustainable buyers buy or use sustainable products from several product categories even outside the retail store include regional products, bio products, fair trade products, products from recycled material, products from regrowing resources and renewable energy. 62.5% bought a sustainable product on the last shopping trip but only 45% of the participants identified with LOHAS. Thus the research shows a mismatch between those who identify themselves as LOHAS and those who buy sustainable products, possibly because not all consumers who buy sustainable products want to be seen as “greenies”. The main challenge in developed countries will therefore be to target sustainable buyers without positioning out of mainstream and becoming “too green” and perhaps communicating other responsibility benefits like ethical or social factors instead. Consequently, many companies in developed countries move away from simple CSR activities towards CM campaigns.

Cause-Related Marketing

CM is a “commercial activity by which a business with a product, service or image to market builds a relationship with a cause or a number of causes for mutual benefit” (Adkins, 1999, p. 11). The parties involved in CM are interdependent and the activity is profit-oriented. CM is therefore not to be confused with social marketing as both business partners aim to achieve commercial objectives (Donovan and Henley, 2010, p. 10). Social marketing “refers to the application of marketing principles, concepts and tools to problems of social change” (Belz and Peattie, 2012, p. 26). Social marketing campaigns are often planned by NGOs and are concerned with macromarketing issues like for example public health, human rights or wilderness protection (Belz and Peattie, 2012, p. 26). They are not profit-oriented and usually involve the “de-marketing of products” (Belz and Peattie, 2012, p. 303). Social marketing campaigns are “generally not based around a physical product” and therefore pricing or product placement issues do not need to be addressed (Belz and Peattie, 2012, p. 304). Because social marketing campaigns try to reduce consumption of products like e.g. cigarettes, alcohol or fast food, they work in opposition of corporate marketing campaigns which try to sell these products (Belz and Peattie, 2012, p. 26).

The financial service provider American Express is often cited in the literature as a pioneer in CM. In the 1980s, American Express supported the restoration of the Statue of Liberty in the USA with a promotional campaign which constituted the first well-known CM project. Consumers were able to donate 1 cent for the restoration of the statue with each transaction they made with their American Express card. The company, as a result, gained considerable attention (Adkins, 1999, p. 14). This example explains the simple concept of CM: consumers support a social organisation with their product purchase with which the manufacturer of the product forms a partnership (Donovan and Henley, 2010, p. 10).

CM is increasingly gaining attention and has also arrived in the marketing strategies of companies in the consumer goods industry (Du et al., 2007). When purchasing consumer goods buyers are more likely to switch between homogeneous products. Companies have therefore identified corporate social initiatives as an appropriate instrument to achieve a higher level of differentiation (Lancaster and Withey, 2007, p. 257; Du et al. 2007).

In the literature CM is also defined as a “win, win, win situation” for all parties involved: the business, the charity and the consumer (BITC, 2004, p. 3). CM thus takes a “macromarketing” perspective focusing on goals outside the individual organisation (Belz and Peattie, 2009, p. 26).

Research indicates that CM offers various benefits for companies. A recent study about CM in Germany, for instance, revealed that 93.9 % of all consumers are able to recall at least one CM campaign. In Germany, the Krombacher Regenwaldprojekt in 2002 achieved the most attention in this regard (Oloko, 2008, p. 11, 21). The campaign promoted that the purchase of one beer crate saves one square meter of rainforest. Further studies found that consumers are willing to switch to a brand which is advertised by CM initiatives when they perceive that product, quality and price are similar to their usual choice. Altogether, increased participation and loyalty among customers were reported (BITC, 2004, p. 4).

Research has revealed that consumers may see the amelioration of the image as a primary reason why businesses engage in CM. More specific, consumers suspect increasing profit to be a major motivation behind CM activities (Oloko, 2008, p. 21). Cui et al. (2003, p. 311) have even found that consumers may have a less favourable attitude towards a company as a result. Therefore considerate steps need to be undertaken to maintain a credible image and to reduce scepticism among consumers when implementing CM as a promotional tool. Ellen et al. (2000, p. 396) suggests that consumers need to find convincing elements in the structure of a campaign to resolve their doubts about the self-interested behaviour of businesses.

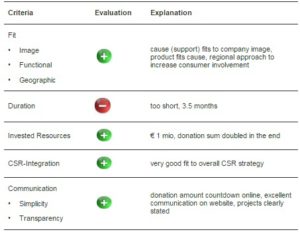

Success Factors in CM

A CM campaign should firstly be accompanied by a suitable degree of fit which can be categorised into image fit, functional fit and geographic fit (factor 1 in Graph 2). Image fit refers to the degree to which cause and company fit together whereas functional fit indicates how well product and cause fit together (Bingé-Alcaniz et al. 2009, p. 438). Oloko (2008, p. 15) moreover states that national products can be more suitably promoted with national campaigns whereas regional products are more appropriate for regional campaigns which corresponds to geographic fit.

A CM campaign should also last for a longer period of time in order to allow consumers to establish a suitable cognitive link (factor 2 duration). Till and Nowak (2000, p. 483) found that long-term campaigns are more likely to stay in consumer’s minds over time as the association between product and cause has been strengthened through repetition. Therefore, length and frequency of support can be regarded as a factor which contributes to the success of a CM campaign.

Graph 2: Success Factors in CM

The financial contribution (factor 3) of a company should be high according to Brink et al. (2006). The author found that a higher financial engagement of a company is commonly appreciated and valued by consumers. Oloko (2008, p. 21) adds that consumers doubt that the average financial contribution of companies is more than 5%. Consequently, the financial commitment of a company can be regarded as a factor achieving great attention among consumers.

The campaign should, moreover, be part of a company’s CSR concept (factor 4 CSR integration). Campaigns which are integrated in an overall CSR approach have, according to CSR Europe (2000, p. 20), been found to achieve a high level of credibility and differentiation.

All these components of CM should be communicated in a simple and transparent way (factor 5) (BITC, 2004, p. 9).

The Example of HARIBO’s CSR Campaign

Company Background

HARIBO is a traditional German sweets company that was founded in 1920 in Bonn. Just two years later the founder Hans Riegel invented the “Dancing Bear”, the figure of a bear made from fruit gum, which became world-famous as the HARIBO Goldbear. Within 10 years the company has increased its product portfolio and has added liquorice products to the markets. The company grew from 160 employees in 1930 to 1000 employees in 1957. In the mid-60s, the advertising slogan “HARIBO makes children happy- and adults too” was heavily promoted. The English version is “Kids and grown-ups love it so, the happy world of HARIBO”. In 1962 HARIBO aired its first TV commercial with the slogan. Today the slogan has a 98% recognition rate in Germany. In all promotion activities HARIBO positions itself as a family company with traditional background (HARIBO Brochure, n.d).

HARIBO has 5 production sites in Germany and further 13 all over Europe. The company currently exports to more than 105 countries all over the globe. HARIBO’s international expansion started in the 1980’s and 1990’s with setting up offices in the US, acquisitions in France and Italy and sales organisations in Norway and Finland. HARIBO continued to expand into Spain, Belgium and Ireland. In the end of the 1990’s and early 2000’s the company started to expand to eastern markets like the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovania and Russia. In 2001 HARIBO bought the Turkish fruit-gum and Marshmallow manufacturer Pamir Gıda Sanayi A.Ş. Thus, Muslim regions in Arab countries, Turkey and the Balkans became new sale zones for HARIBO. In every Turkish supermarket consumers can buy Halal-HARIBO’s today (Haribo Turkey, n.d).

Promotion activities were always carefully planned by HARIBO. Today, the HARIBO Goldbear has become a best-seller all over the world and has become a symbol of fruit gum (HARIBO Brochure, n.d). In 1991 the company started to work with celebrity endorser Thomas Gottschalk. He is a charismatic entertainer whose popularity extends to all levels of German society. The partnership is the longest-running celebrity endorsement of this kind in the world (HARIBO Brochure, n.d).

HARIBO understood very early that CSR is important to their target group. Each October since 1936, children and adults can trade in chestnuts and acorns for HARIBO sweets in Bonn. For 10 kg of chestnuts or 5 kg of acorns, children can receive 1 kg of HARIBO sweets. The nuts are then fed to wild animals through the winter. Furthermore, in 1987 Dr. Hans Riegel established a foundation to encourage, promote and inspire talented youth in Germany. Students with financial and nonmaterial needs receive special grants by the foundation (HARIBO Brochure, n.d). This focus on humans and animals in need fits very well and HARIBO has continued to develop CSR and CM campaigns with this focus.

HARIBO’s CM Campaign

The national campaign was launched in Germany by the sweets company HARIBO in collaboration with the organisation Ein Herz für Kinder (A Heart for Children), which is a very well known German organization that has helped children in need for more than 30 years. The partner organisation Ein Herz für Kinder is an organisation founded by the publisher of the largest popular newspapers (BILD by Axel Springer). The organisation’s aim is to help children who need support (Ein Herz für Kinder, 2008).

HARIBO connects its product gummy bears with children. This connection can be seen as a suitable link between product and cause since HARIBO’s customers particularly associate the product with the terms home and childhood (Baumgartner, 2007, p. 81).

The campaign was carried out for a 3.5-months period between 14 December 2009 and 30 March 2010. Consumers were able to support Ein Herz für Kinder with 1 cent per purchase of a package of GOLDBÄREN or SAFT-GOLDBÄREN (gummy bears) they consumed. In terms of the invested resources, HARIBO states on its homepage that € 1,000,000 have been collected for the campaign after a six-month period. The company HARIBO doubled the donation sum of which 16 projects in each federal state of Germany finally benefited (HARIBO, n.d. a, b). For example:

- Some money was given to the institute of forensic medicine in Mainz, where traumatised children who suffered from violence get support and medical treatment in an appropriate and supportive environment.

- The protestant church in Maintal-Dörnigheim received money to provide lunch for children in need.

- Another example is the refurbishment of a run-down playground in Bad Frankenhausen, where many children used to injure themselves by accident.

- In Bavaria, the association for children with cancer or disabilities received money to build a house parents can stay in and get mental support while their children receive medical treatment in hospital.

- In the north of Germany, 80 children from disadvantaged families get the opportunity and receive several service offers in a “house for teenagers”. They get help with their homework, a food allowance to eat in school and participate in many free-time activities to develop their personality.

- In other parts of Germany several day-care centres and organisations who help children received money to improve their facilities.

HARIBO aims to keep consumers highly informed and provides transparent communication. The campaign webpage communicated the donation amount openly on a real-time basis and clearly described the associated social projects online. Customers were able to access information about the 16 projects via a map of Germany (see Graph 3). Clear descriptions accompany the communication approach. In addition to the mentioned communication approaches, HARIBO also promoted its Ein Herz für Kinder campaign through launching a TV spot with the celebrities Thomas Gottschalk and Michelle Hunziker as testimonials (HARIBO, n.d. f). Moreover, the company implemented a mobile advertising campaign where interested consumers were able to make their contribution via sms and could donate without necessarily buying the product (HARIBO, n.d. g).

Graph 3: Online Presence with Description of the 16 Supported Projects (HARIBO (N.D. D))

HARIBO’s CM Campaign Evaluation

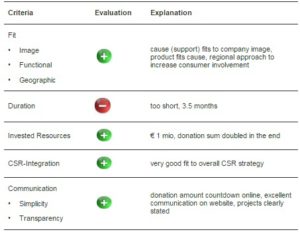

The evaluation of the five success factors in Table 1 shows that the campaign was a great success. Image, functional and geographic fit were superb. The focus on children fits to the company image very well and the use of sweets as a product fit the cause of helping children in need. Since HARIBO supported projects in all German federal states, geographic proximity to the consumer was guaranteed.

Furthermore, the campaign is well integrated into the overall CSR-Strategy which has always focused on children since the company started to engage in CSR activities in 1936. HARIBO’s regional approach increased consumer involvement so that each consumer was able to link his contribution to a local project. The online communication of the contribution was very transparent and reduced consumer scepticism that the money is kept for HARIBO’s profit. Only the time-frame was relatively short with 3.5 months and should have been extended. The campaign can therefore serve as a helpful guideline from which other companies can learn.

Table 1: Campaign Evaluation Based on the 5 Success Factors

Conclusion and Lesson’s Learned for MENA

Although the HARIBO CM campaign was highly successful in Germany, it is advisable for companies in the MENA region to not simply copy CSR strategies from developed countries. The case shows that an adaptation to local needs is required to increase consumer involvement. CSR campaigns in developing countries should focus on basic needs, educational purposes and gaps in local developments as outlined by Lacy and Hayward (2011, p. 351). Also the stakeholder group should be considered carefully. The CM campaign of HARIBO clearly demonstrated that stakeholders need to see the benefit of the campaign and the personal relevance. Therefore, companies in the MENA region should communicate the cause carefully and make sure that the benefit is clear to all consumers. In addition, a CM campaign should be of sufficient length to be recognised by consumers. An arbitrary CM campaign with a random good cause that is not linked to the company product, image and location is not likely to succeed. Any CM campaign should therefore be embedded into the company’s CSR strategy. Consequently companies should already consider the 5 success factors during the development stage of the campaign.

Case Questions:

- Considering that Germany is a developed country, did HARIBO target the right stakeholder group and the right issues or benefits?

- According to the information presented how would HARIBO’s CM campaign need to differ in the MENA region? Could the level of customer involvement be an explanation for this difference?

- Consider the culture of the country you currently live in. How would a sweets CM campaign from a local company need to differ compared to the GERMAN example of HARIBO? Refer to Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions in your answer.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Adkins, S. (1999). Cause Related Marketing: Who Cares Wins, Burlington: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Belz, F.- M. (2012). Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective, Second Edition. Chichester: Wiley.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Belz, F. M. & Peattie, K. (2009). Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective, Chichester: Wiley.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Berniak-Woźny, J. (2010). Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries: Polish Perspective in Williams, S. (2010) Reframing Corporate Social Responsibility: Lessons Learned from the Global Financial Crisis (Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance and Sustainability), 1, 271-295. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Bigné-Alcaniz, E., Currás-Pérez, R. & Sánchez-García, I. (2009). “Brand Credibility in Cause-Related Marketing: The Moderating Role of Consumer Values,” Journal of Product and Brand Management 18(6), 437-438.

Publisher – Google Scholar

BITC (2004). Brand Benefits: How Cause Related Marketing Impacts on Brand Equity, Consumer Behaviour and the Bottom Line, (online: http://www.bitc.org.uk/resources/publications/brand_benefits.html; accessed: 25 February 2011).

Publisher

Blackwell, R. D., Miniard, P. W. & Engel, J. F. (2001). Consumer Behavior, 9th edn, Fort Worth: Hartcourt College Publishers.

Publisher

Blowfield, M. & Murray, A. (2011). Corporate Responsibility, (2nd Ed). Oxford: Oxford.

Publisher

Brink, D. v., Oedekern-Schröder, G. & Pauwels, P. (2006). “The Effect of Strategic and Tactical Cause-Related Marketing on Consumers’ Brand Loyalty,” Journal of Consumer Marketing 23(1), 15-25.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Cui, Y., Trent, E. S., Sullivan, P. M. & Matriu, G. N. (2003). “Cause-Related Marketing: How Generation Y Responds,” Journal of Retail and Distribution Management 31(6), 310-320.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Donovan, R. & Henley, N. (2010). Principles and Practice of Social Marketing: An International Perspective, (2nd Ed). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B. & Sen, S. (2007). “Reaping Relational Rewards from Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Competitive Positioning,” International Journal of Research in Marketing 24(3), 224-241.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ein Herz für Kinder (2008). Das sind wir!: Wir mischen uns dort ein, wo Kinder Hilfe brauchen” (online: http://www.ein-herz-fuer-kinder.de/EHFK/deutsch/ueber-uns/das-sind-wir/das-sind-wir.html; accessed: 17 April 2011)

Publisher

Ellen, P. S., Mohr, L. A. & Webb, D. J. (2000). “Charitable Programs and the Retailer: Do they Mix?,” Journal of Retailing 76(3), 393-406.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

European Commission (2011). Sustainable and Responsible Business: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), (online: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sustainable-business/corporate-social-responsibility/index_en.htm; accessed: 12 April 2011).

Publisher

HARIBO Brochure (n.d). The Coulorful World of HARIBO (online: http://www2.haribo.com/fileadmin/upload/Germany/Zahlen_Fakten/HARIBO_info_en.pdf; accessed: 5 October 2011).

HARIBO (n.d. a). HARIBO und die Verbraucher spendeten gemeinsam 1.000.000 Euro der Hilfsorganisation “Ein Herz für Kinder,” (online: http://herz.haribo.de/#/Info; accessed: 17 April 2011).

Publisher

HARIBO (n.d. d). Danke! (online: http://herz.haribo.de/#; accessed: 17 April 2011).

HARIBO (n.d. b). HARIBO und BILD hilft e.V. “Ein Herz für Kinder” helfen Projekten in der Nähe, (online: http://herz.haribo.de/#/Project; accessed: 17 April 2011).

HARIBO (n.d. f). Exklusiver Spendenaufruf durch Thomas Gottschalk und Michelle Hunziker! (online: http://herz.haribo.de/#/Spots; accessed: 2 Mai 2011).

HARIBO (n.d. g). HARIBO-Kampagne mit mobiler Unterstützung, (online: http://herz.haribo.de/#/Mobile; accessed: 2 Mai 2011).

HARIBO Turkey (n.d). The Early Years of HARBO, (online: http://www.haribo.com/planet/tr_en/info/core/history/first_years.php; accessed: 6 October 2011).

Harrison, R., Newholm, T. & Shaw, D. (2005). The Ethical Consumer, London: Sage Publications.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hollensen, S. (2010). Global Marketing, 5th Edition, Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Publisher

Koldertsova (2010). “The Second Corporate Governance Wave in the Middle East and North Africa,” OECD Journals 2, 219-226.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kotler, P. & Lee, N. (2005). Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause, New Jersey, John Wiley and Sons.

Publisher – Google Scholar

KPMG (2008). KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2008, (online: http://www.kpmg.de/docs/Corp_responsibility_Survey_2008.pdf; accessed: 4 Mai 2011).

Publisher

Lacy, P. & Hayward, R. (2011). “A New Era of Sustainability in Emerging Markets? Insights from a Global CEO Study by the United Nations Global Compact and Accenture,” Corporate Governance 11(4), 348-357.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lancaster G. & Withey, F. (2007). The Official CIM Coursebook: Marketing Fundamentals, Oxford: Elsevier.

Publisher

Mehanna, R.- A., Yazbeck, Y. & Sarieddine, L. (2010). “Governance and Economic Development in MENA Countries: Does Oil Affect the Presence of a Virtuous Circle?,” Journal of Transnational Management 15, 117-150.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Oloko, S. (2008). Cause Related Marketing: Der Status Quo in Deutschland, Universität Potsdam (online: http://www.makingsense.de/media/Downloads/Studie_CauserelatedMarketing_Deutschland_Bericht_Juli2008.pdf; accessed: 25 February 2011).

Publisher

Peters, S., Miller, M. & Kusyk, S. (2011). “How Relevant is Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility in Emerging Markets?,” Corporate Governance 11(4), 429-445.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T. & Schumann, D. (1983). “Central and Peripheral Routes to Advertising Effectiveness: The Moderating Role of Involvement,” Journal of Consumer Research 10, 135-136.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rizk, R., Dixon, R. & Woodhead, A. (2008). “Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting: A Survey of Disclosure Practices in Egypt,” Social Responsibility Journal 4(3), 306-323.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Robbins, S. P. & De Cenzo. D. A. (2001). Fundamentals of Management, (3rd Ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Sheikh, S. & Beise-Zee, R. (2011). “Corporate Social Responsibility or Cause-Related Marketing? The Role of Cause Specificity of CSR,” Journal of Consumer Marketing 28(1), 27-39.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Solomon, M. R., Barnossy, G., Askegaard, S. & Hogg, M. K. (2010). Consumer Behaviour – A European Perspective, 4th Edn. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Publisher

Steffen, A. (2010). ‘Understanding the Green Consumer, Presentation at the second HIB Spring Conference on Ethics, Sustainability and Service Ethos- to Whom is Business Responsible?,’ Heidelberg, April 23 2010, Germany, Heidelberg.

Till, B.D. & Nowak, L. I. (2000). “Toward Effective Use of Cause-Related Marketing Alliances,” Journal of Product and Brand Management 9(7), 472-484.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Williams, A. (2008). ‘The Enemies of Progress – The Dangers of Sustainability,’ Exeter: Societas.

Google Scholar

Williams, S. (2010). Reframing Corporate Social Responsibility: Lessons Learned from the Global Financial Crisis, (Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance and Sustainability), Volume 1, 271-295. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Publisher

West, D., Ford, J. & Ibrahim, E. (2010). ‘Strategic Marketing,’ (2nd Ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.