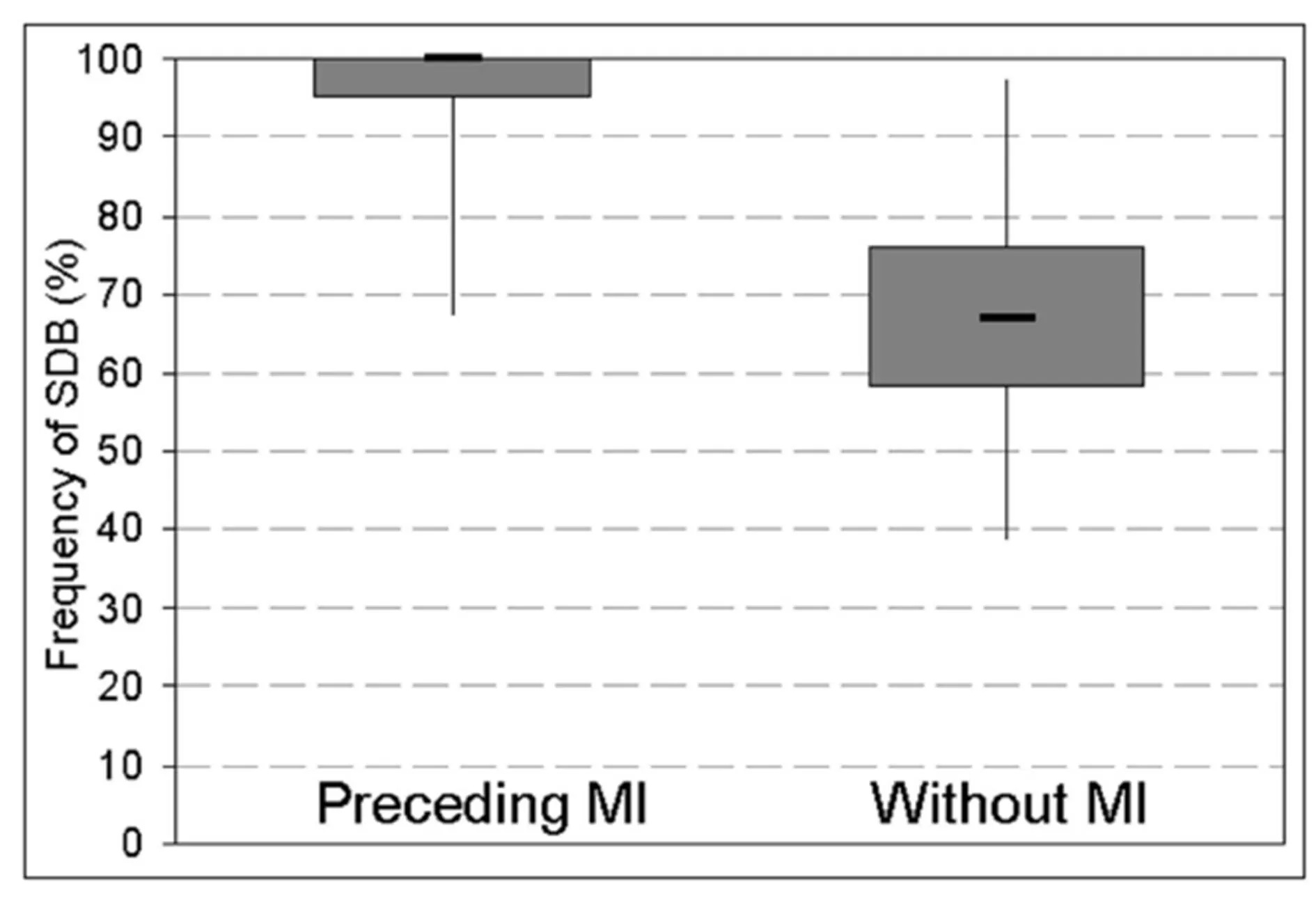

The present results indicate a high frequency of previously unrecognized and therefore untreated OSA in a group of patients with CAD. An AHI of ≥ 5/h with consecutive reduction of arterial oxygen saturation was observed in all recruited patients. Of note, all patients with myocardial ischemia during the observation period experienced OSA in the preceding period of 900 seconds.

A high prevalence of OSA in patients with CAD has been previously demonstrated by Shahar et al. (2001) and Peker et al. (2002). Marin and co-workers (2005) showed higher incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with OSA in comparison to patients without. Furthermore, SDB was associated with re-stenosis, remodeling (Steiner et al. 2008) and cardiac mortality after percutaneous intervention as shown by Yumino et al. (2007). Treatment of SDB with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) was presumed by Drager et al. (2007) to impede progression of atherosclerosis to clinically important cardiovascular diseases. Milleron and colleagues (2004) showed a reduction of new cardiovascular events in patients with CAD when sleep disordered breathing had been treated by CPAP-therapy. On the other hand, Shah and colleagues (2013) found OSA to have a protective role in acute myocardial infarction by chronic but mild intermittent hypoxic preconditioning.

In the present study, a temporal association of nocturnal respiratory disorders on myocardial ischemia was hypothesized. As described by other authors, nocturnal impairment of oxygen saturation occurred frequently, whereas myocardial ischemia was only detected in less than 50% of the study population during the study night. The presumed temporal association was controversial discussed in the literature. Keyl and colleagues (1994) as well as Smith and co-workers (1996) found no association between oxygen saturation and myocardial ischemia, whereas Reeder et al. (1991) described myocardial ischemia as temporally associated with hypoxemia. These results are in agreement with our findings, as accumulation of OSA events preceding episodes of myocardial ischemia was found.

Arbab-Zadeh and co-workers (2009) demonstrated the inability of diseased coronary artery segments to react to hypoxemia. However, all patients of the study population had diseased coronary arteries. Thus, other factors i.e. rapid-eye-movement (REM) and non-REM sleep should be considered. Kim and colleagues (2008) found severe myocardial ischemia in an animal model with stenosed coronary arteries during non-REM sleep. Nocturnal myocardial ischemia potentially occurs if oxygen partial pressure in blood has fallen below a critical level. This threshold probably differs between subjects. Temporal and accumulating SDB as shown in the present study would lead to reduced level of oxygen partial pressure.

Limitations and Strength

The present study was not performed with polysomnography (PSG). Therefore, an allocation of myocardial ischemia to sleep stages was not possible. It should be mentioned that nocturnal ischemic events frequently occur in REM sleep as shown by Schäfer et al. (1997). Furthermore, heart rate as an important determinant of myocardial oxygen consumption was not assessed and analyzed.

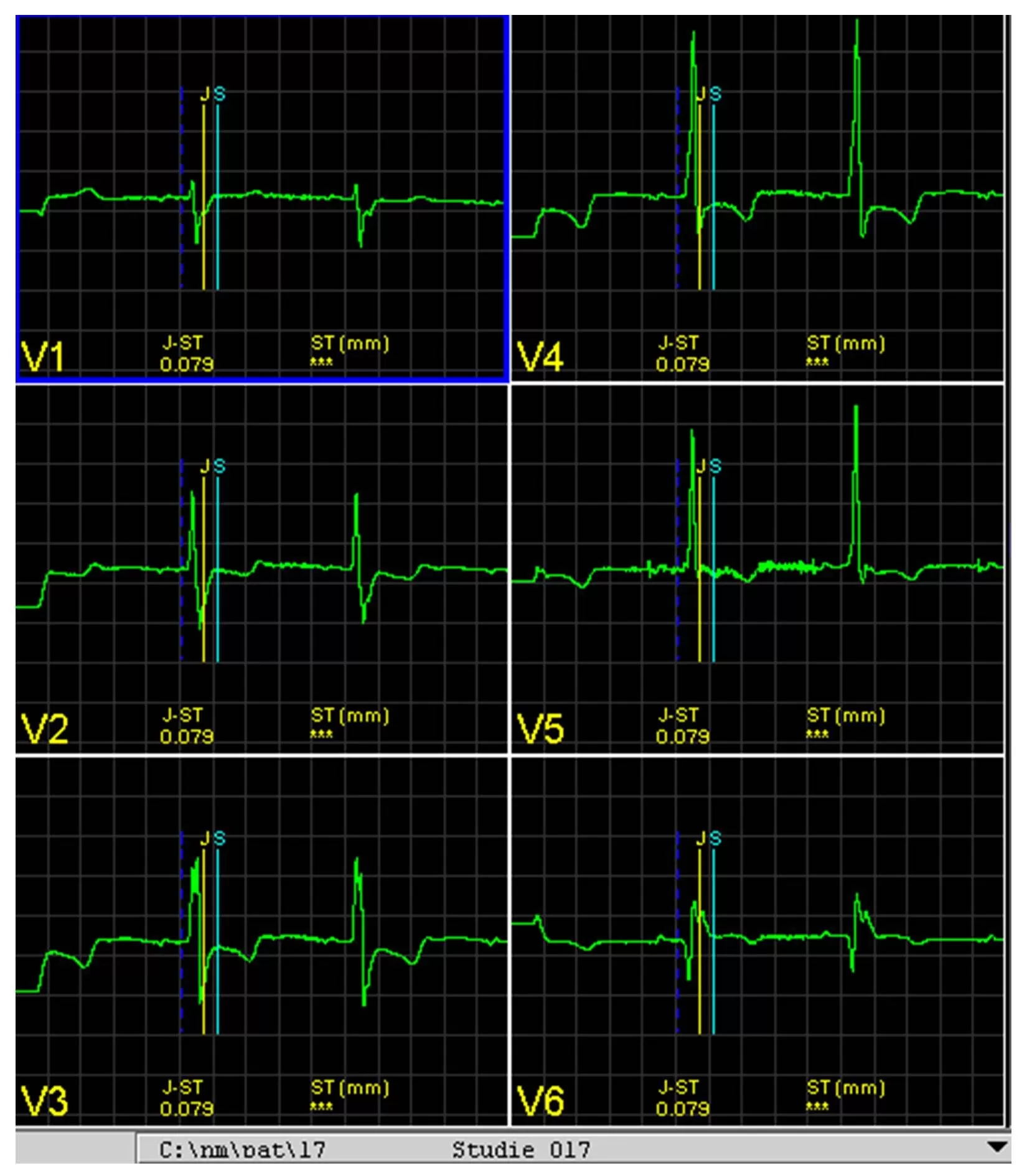

Due to its small sample size, the power of the study is limited. However, to the best of our knowledge this is the first study that employed long-term 12-lead-ECG for the detection of nocturnal myocardial ischemia associated with cardio-respiratory polygraphy. Body position while measuring ST abnormalities was not addressed within the analysis.

The present study concludes that nocturnal myocardial ischemic events frequently occur with a temporal related accumulation of preceding SDB.

References

1. Arbab-Zadeh A, Levine BD, Trost JC, Lange RA, Keeley EC, Hillis LD, Cigarroa JE (2009) “The effect of acute hypoxemia on coronary arterial dimensions in patients with coronary artery disease,” Cardiology 113:149-54.

Publisher – Google Scholar

2. Drager LF, Bortolotto LA, Figueiredo AC, Krieger EM, Lorenzi GF (2007) “Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on early signs of atherosclerosis in obstructive sleep apnea,” Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176:706-12.

Publisher – Google Scholar

3. Franklin KA, Nilsson JB, Sahlin C, Näslund U (1995) “Sleep apnoea and nocturnal angina,” Lancet 345:1085-7.

Publisher – Google Scholar

4. Gögenur I, Rosenberg-Adamsen S, Lie C, Carstensen M, Rasmussen V, Rosenberg J (2004)

“Relationship between nocturnal hypoxaemia, tachycardia and myocardial ischaemia after major abdominal surgery,” Br J Anaesth 93:333-8

Publisher – Google Scholar

5. Keyl C, Lemberger P, Rödig G, Dambacher M, Frey A (1994) “Hypoxaemia and myocardial ischaemia on the night before coronary bypass surgery,” Br J Anaesth 73:157-61.

Publisher – Google Scholar

6. Kim SJ, Kuklov A, Kehoe RF, Crystal GJ (2008) “Sleep-induced hypotension precipitates severe myocardial ischemia,” Sleep 31:1215-20.

Publisher – Google Scholar

7. Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG (2005) “Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study,”Lancet 365:1046-53.

Publisher – Google Scholar

8. Martinez D, Klein C, Rahmeier L, Pacheco da Silva R, Fiori CZ, Cassol CM, Goncalves SC, Goncalves Bos AJ (2012) “Sleep apnea is a stronger predictor for coronary heart disease than traditional risk factors,” Sleep Breath 16:695-701

Publisher – Google Scholar

9. Milleron O, Pillière R, Foucher A, de Roquefeuil F, Aegerter P, Jondeau G, Raffestin BG, Dubourg O (2004)

“Benefits of obstructive sleep apnoea treatment in coronary artery disease: a long-term follow-up study,” Eur Heart J 25:728-34.

Publisher – Google Scholar

10. Mooe T, Franklin KA, Wiklund U, Rabben T, Holmström K (2000) “Sleep-disordered breathing and myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease,” Chest 117:1597-602.

Publisher – Google Scholar

11. Peker Y, Hedner J, Norum J, Kraiczi H, Carlson J (2002) “Increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged men with obstructive sleep apnea: a 7-year follow-up,” Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:159-65.

12. Reeder MK, Muir AD, Foëx P, Goldman MD, Loh L, Smart D (1991) “Postoperative myocardial ischaemia: temporal association with nocturnal hypoxaemia,” Br J Anaesth 67:626-31.

Publisher – Google Scholar

13. Schäfer H, Koehler U, Ploch T, Peter JH. (1997) Sleep-related myocardial ischemia and sleep structure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and coronary heartdisease. Chest. 1997;111:387-93.

Publisher – Google Scholar

14. Shah N, Redline S, Yaggi KH, Wu R, Zhao CG, Ostfeld R, Menegus M, Tracy D, Brush E, Appel WD, Kaplan RC (2013) “Obstructive sleep apnea and acute myocardial infarction severity: ischemic preconditioning?” Sleep Breath 17:819-26

Publisher – Google Scholar

15. Shah NA, Yaggi HK, Concato J, Mohsenin V (2010) “Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for coronary events or cardiovascular death,” Sleep Breath 14:131-36

Publisher – Google Scholar

16. Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, Lee ET, Newman AB, Javier Nieto F, O’Connor GT, Boland LL, Schwartz JE, Samet JM (2001) “Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study,” Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163:19-25.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17. Smith HL, Sapsford DJ, Delaney ME, Jones JG (1996) “The effect on the heart of hypoxaemia in patients with severe coronary artery disease,” Anaesthesia 51:211-8.

Publisher – Google Scholar

18. Steiner S, Schueller PO, Hennersdorf MG, Behrendt D, Strauer BE (2008) “Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on the occurrence of restenosis after elective percutaneous coronary intervention in ischemic heart disease,” Respir Res 9:50.

Publisher – Google Scholar

19. Yumino D, Tsurumi Y, Takagi A, Suzuki K, Kasanuki H (2007) “Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on clinical and angiographic outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome,”

Am J Cardiol 99:26-30.

Publisher – Google Scholar