Introduction

In recent times, nickel-titanium (NiTi) alloys, which were first reported in the 1960s by W.E. Buehler, have been popularly used in root canal treatment (Buehler et al. 1968). They are increasingly being used by general dentists and endodontists for cleaning and shaping procedures (Parashos et al. 2004, Madarati et al. 2008a, Madarati et al. 2008b, Er et al. 2011). NiTi rotary files show high elasticity and resistance to plastic deformation. These files are faster than hand files (Short et al. 1997), and in terms of centering ratio and amount of transportation, NiTi rotary files show good results (Ersev et al. 2010).

Despite their advantages, NiTi instruments also have a high risk of unexpected fracture (Pruett et al. 1997, Ankrum et al. 2004, Gencoglu et al. 2009). Instrument fracture often results from incorrect use or overuse (Gambarini 2001). NiTi instruments tend to separate seven times more frequently than do hand instruments, and they are more likely to separate in the apical third of narrow canals such as those of maxillary and mandibular molars (Spili et al. 2005, Iqbal et al. 2006).

Among NiTi rotary files, ProTaper® Universal rotary files (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) were designed with increasing tapers. The ProTaper® Universal system consists of three shaping files and three finishing files (Wu et al. 2011). However, the design of these ProTaper® files reduces the torsional loads, instrument fatigue, and separation possibility. The separation of these files has been investigated in vitro, but few studies have reported what actually happens in clinics (Blum et al. 2003, Simon et al. 2008).

Materials and Methods

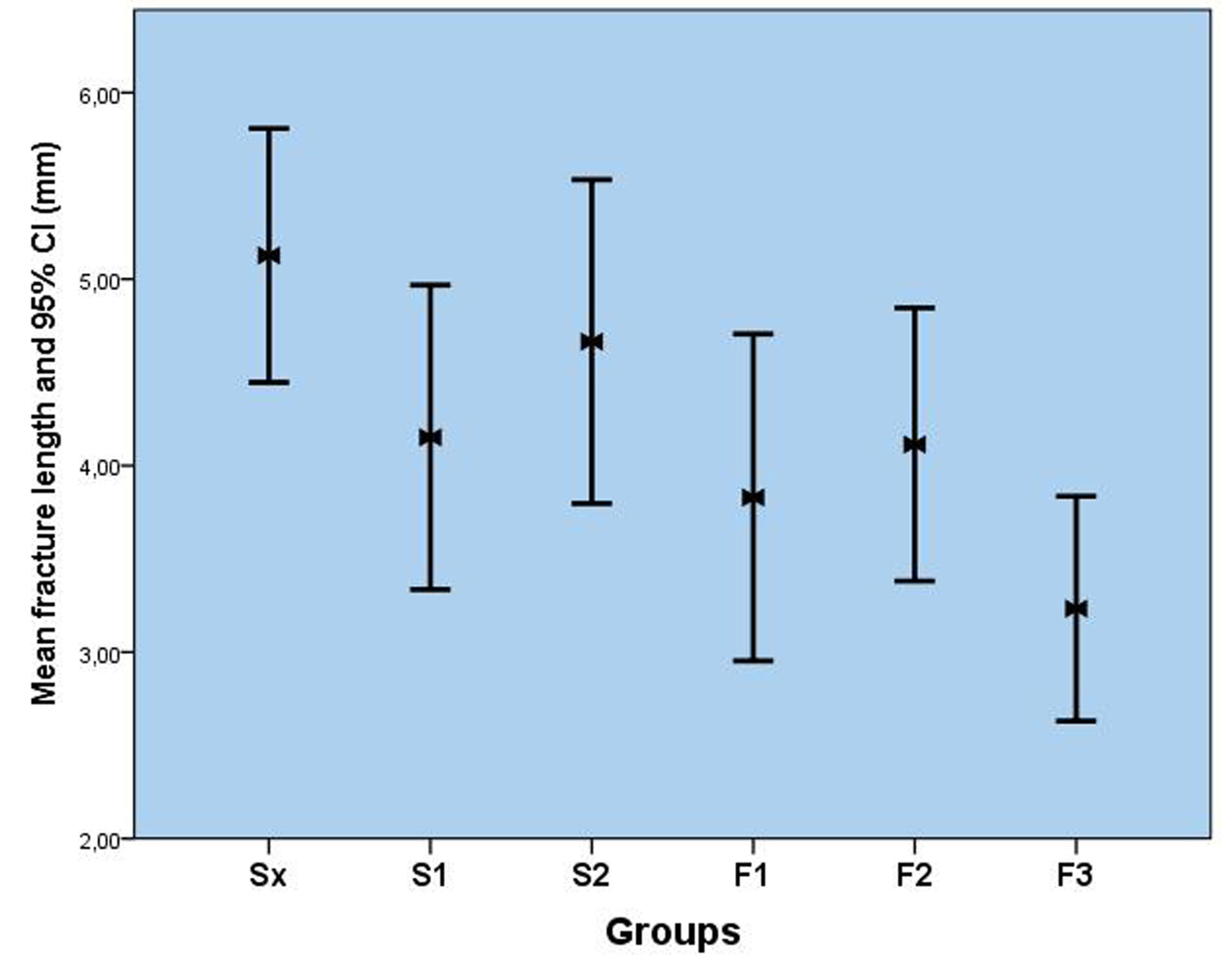

The protocol of this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Izmır Katip Celebi University. First, numerous clinics in Izmır, Turkey, were identified, and containers were placed at these clinics for collecting broken files. The clinicians were instructed to discard files used used with an electric motor (X- Smart; Dentsply Maillefer) in very complex and severely curved or calcified canals but in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations . 120 files that separated during routine clinical endodontic procedures were classified into the following six groups according to their type: Sx, S1, S2, F1, F2, and F3 (Figs. 1). The classified instruments were cleaned ultrasonically and autoclaved. The length of the separated file was measured using an electronic digital caliper, and then, the separation length of each file was determined by subtracting the length at which separation occurred from the nonseparated file length . The obtained data was analyzed statistically by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-hoc test using SPSS software.

Discussion

Most previous studies evaluated such files using controlled and standardized approaches. However, no studies have investigated the outcomes in non-controllable clinics. Wu et al. (2011) evaluated whether relevant factors influence the fracture of ProTaper® Universal rotary files. Their results showed that multiple factors contributed to the separation of ProTaper® Universal rotary files. However, in the present study, the relevant factors were not analyzed using a standardized in vitro approach; instead, this study focused on the outcome of clinically used ProTaper® Universal rotary files.

If a fractured NiTi fragment is not removed successfully, as in the case of high standards root canal treatment, it would hinder the control of microbial growth in the root canal beyond the obstruction (Spili et al. 2005). On the other hand, in the apical third, fragments are left behind because of the risk of perforation during removal attempts (Fors et al. 1986). Therefore, instrument separation should be considered from different viewpoints.

First, the evaluation of separated Sx files showed that the Sx rotary file separated at a higher point compared to the other files. This result is interesting because Sx rotary files are used more coronally than are others. The S2 file showed the second-highest separation length. This was attributed to the tapering design of the file. Both Sx and S2 files exhibit nine increasingly larger tapers that respectively range from 0.035 to 0.19 and from 0.04 to 0.115. However, S1 files exhibit 12 increasingly larger tapers that range from 0.02 to 0.11, and F1, F2, and F3 files have fixed tapers of 0.07, 0.08, and 0.09 from D1 to D3. After D3, the taper of these files decreases and the remainder of the file experiences relatively less force. D3 corresponds to 4-mm length from the tip of the file, and our results showed that fractures generally occurred at this length owing to the high taper and high force.

Second, S1, S2, F1, F2, and F3 files, all of which reach the apical part, were separated with lesser fragments. This was attributed to the larger diameter of the coronal third, which prevents these instruments from tightening in this third small diameter and in complex canal divisions in the apical thirds where tightening could occur (Iqbal et al. 2006).

In the present study Sx rotary file separated at a higher point compared to the other files. This result could be important because Sx rotary files are used more coronally than others. When the separation length increases, the unfilled area will be increased between the flute of the file and the root canal wall. Thus, this could result in failure of the root canal treatment.

Because of the limitations of the materials and the methods of this study, it could not be estimated where or when a file will be separated in a clinical setting. Having said that, a correlation was found to exist between different sizes of ProTaper® Universal rotary files with regard to of the length at which separation occurred. The Sx files were the longest separated files. This means that if they break and cannot be removed, they could cause more complications than would the other ProTaper® Universal files, because of unfinished chemomechanical preparation at the unreached part of the root canal system.

Acknowledgement:

The authors deny any conflict of interest related to this study.

References

1. Ankrum MT, Hartwell GR, Truitt JE (2004) K3 Endo, ProTaper, and ProFile systems: breakage and distortion in severely curved roots of molars. Journal of endodontics 30: 234-7.

Publisher – Google Scholar

2. Blum JY, Machtou P, Ruddle C, Micallef JP (2003) Analysis of mechanical preparations in extracted teeth using ProTaper rotary instruments: value of the safety quotient. Journal of endodontics 29: 567-75.

Publisher – Google Scholar

3. Buehler W, Wang F (1968) A summary of recent research on the Nitinol alloy and their potential application in ocean engineering. Ocean Engineering: 105-20.

Publisher – Google Scholar

4. Er K, Tasdemir T, Siso SH, Celik D, Cora S (2011) Fracture resistance of retreated roots using different retreatment systems. European journal of dentistry 5: 387-92.

5. Ersev H, Yilmaz B, Ciftcioglu E, Ozkarsli SF (2010) A comparison of the shaping effects of 5 nickel-titanium rotary instruments in simulated S-shaped canals. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics 109: e86-93.

Publisher – Google Scholar

6. Fors UG, Berg JO (1986) Endodontic treatment of root canals obstructed by foreign objects. International endodontic journal 19: 2-10.

Publisher – Google Scholar

7. Gambarini G (2001) Cyclic fatigue of ProFile rotary instruments after prolonged clinical use. International endodontic journal 34: 386-9.

Publisher – Google Scholar

8. Gencoglu N, Helvacioglu D (2009) Comparison of the different techniques to remove fractured endodontic instruments from root canal systems. European journal of dentistry 3: 90-5.

9. Iqbal MK, Kohli MR, Kim JS (2006) A retrospective clinical study of incidence of root canal instrument separation in an endodontics graduate program: a PennEndo database study. Journal of endodontics 32: 1048-52.

Publisher – Google Scholar

10. Madarati AA, Watts DC, Qualtrough AJ (2008a) Opinions and attitudes of endodontists and general dental practitioners in the UK towards the intra-canal fracture of endodontic instruments. Part 2. International endodontic journal 41: 1079-87.

Publisher – Google Scholar

11. Madarati AA, Watts DC, Qualtrough AJ (2008b) Opinions and attitudes of endodontists and general dental practitioners in the UK towards the intracanal fracture of endodontic instruments: part 1. International endodontic journal 41: 693-701.

Publisher – Google Scholar

12. Parashos P, Messer HH (2004) Questionnaire survey on the use of rotary nickel-titanium endodontic instruments by Australian dentists. International endodontic journal 37: 249-59.

Publisher – Google Scholar

13. Pruett JP, Clement DJ, Carnes DL, Jr. (1997) Cyclic fatigue testing of nickel-titanium endodontic instruments. Journal of endodontics 23: 77-85.

Publisher – Google Scholar

14. Short JA, Morgan LA, Baumgartner JC (1997) A comparison of canal centering ability of four instrumentation techniques. Journal of endodontics 23: 503-7.

Publisher – Google Scholar

15. Simon S, Lumley P, Tomson P, Pertot WJ, Machtou P (2008) Protaper–hybrid technique. Dental update 35: 110-2, 5-6.

16. Spili P, Parashos P, Messer HH (2005) The impact of instrument fracture on outcome of endodontic treatment.Journal of endodontics 31: 845-50.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17. Wu J, Lei G, Yan M, Yu Y, Yu J, Zhang G (2011) Instrument separation analysis of multi-used ProTaper Universal rotary system during root canal therapy. Journal of endodontics 37: 758-63.

Publisher – Google Scholar