Introduction

Occupation burnout occurs as a result of prolonged exposure of workers to physical and psychological stress which can progressively lead to physical and psychological exhaustion, depersonalization, and low sense of professional accomplishment. Under these conditions, employees enter what is called “a professional burnout zone” which is characterized by a decrease in productivity and lack of job satisfaction (Koev et al, 2019). Teachers’ job stress is a frequent phenomenon which can lead to burnout. Irrespective of their income (Chelwa et al, 2019), teachers can perform well but they can also be more prone to professional burnout (Luk et al, 2010). Burnout is a condition resulting from emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal achievement (Maslach et al., 1996).

The severity of the symptoms of burnout increase with the length of exposure and job demands and the severity of adverse working conditions, increasing the likehood for the development of occupational stress among human service workers, including teachers (Jennett, Harris, & Mesibov, 2003; Rentzou, 2012) which is potentially leading to rapid employee turnover rate (Abuhashesh et al, 2019).

Burnout employees are characterized by high levels of exhaustion and negative attitudes toward their work, absenteeism, reduced productivity, low morale and low job satisfaction (Maslach & Leiter, 1999; Tsigilis et al, 2011; Fang et al, 2016). Long term exposure of workers to physical and psychological stress can result in physical and emotional fatigue. Symptoms of burnout include frustration, mental fatigue, and lack of motivation to perform simple tasks and socialize.

The Burnout syndrome is documented on the basis of its three dimensions (Maslach al. 2001):

1) Emotional exhaustion (characterised by physical and psychological fatigue)

2) Depersonalization (characterised by cynical behaviour and detachment from the job

3) Reduced personal accomplishment (characterised by feeling inefficient / incompetent at work.

Published research studies indicate that teachers’ burnout is an issue of concern for the profession over the past years (Anastasiou et al 2015; Perrone et al, 2019).

There is a considerable evidence to suggest that teachers’ work contributes to the academic performance of their schools (Jackson et al, 2014; Chetty et al, 2014; Chelwa et al, 2019). At the same time, there is substantial evidence indicating that a significant number of teachers may experience high levels of occupational stress at some stages of their career (Kamtsios, 2018; Panagopoulos et al 2014; Ismail et al, 2019; Perrone et al. 2019) that may affect the health and wellbeing of teachers (Solis-Soto et al. 2019) with negative consequences on educational outcomes and school effectiveness.

The global financial crisis had a negative impact on growth, employment and income in many countries. Countries in Central and Eastern Europe were particularly affected by the global economic crisis leading to a dramatic reduction in public spending, lowering of salaries, redundancies and public sector employment freezes including education (Filippidis et al, 2014).

In times of financial crisis, there are changes in the work environment of educational units that may lead to an increase in teachers’ job burnout levels and affect decision-making processes (Leslie & Canwell, 2010; Niessen et al, 2017).

As a result of the economic problems of the Greek central government, austerity measures resulted in the introduction of changes in the working conditions of public servants in Greece. These changes included reduction in the salaries and the number of teachers working in public schools (OECD, 2014; Anastasiou et al, 2015). These changes may have an impact on teachers’ job satisfaction and stress. For example, a combination of austerity measures, taxation, reducing the gross income and purchasing power parity of teachers may create conditions which could lead to increases in job stress (Kyriakoy 2001). During a long period of financial crisis in Greece, teachers’ gross income was dramatically reduced experiencing, at the same time, financial disrespect for their job. In Greece, public servants’ salaries were cut by at least 30% with the country being faced with rising taxation, increased working hours and job insecurity (Panagopoulos et al, 2014), altering the public sector’s safe work environment as it was prior to the economic turmoil in Greece (Grigoriadou & Kleftaras, 2017).

Since 2008 and during the long period of financial crisis, teachers’ gross income in Greece has been dramatically reduced with wage cuts while they were viewed along with other public sector professionals, as non-productive (Filippidis et al, 2014).

The austerity measures led to various public administration decisions including teachers’ relocations after school closures, employment freezes, rising number of teacher’s retirements, increased number of classrooms and the simultaneous decrease in the number of seasonally employed teachers (Panagopoulos et al, 2014). Between 2010 and 2011, for example, there had been a 12% reduction in the teaching workforce in Greece (Fillipidis et al, 2014).

Under such conditions, teachers may experience financial disrespect for the job they are doing (Hock, 1988) being encountered with the need to change their consumption and lifestyle behaviour and habits so as to adjust their spending according to lower wages and gross income to levels of reduction.

Relevant studies on financial hardship have included a number of measures like: lack of money or resources required to meet basic needs; debt, inability to heat one’s home, being unable to pay utility bills on time, having to sell possessions, etc (Richardson et al, 2012; Crowe et al, 016).

There is a number of studies which have emphasized that there is a link between socioeconomic variables and mental health. For example, the relationship between financial hardship and mental health was emphasized in a study exploring changes in the Greek population from 2008 to 2011, where the possibility of the participants in the study suffering from major depression was found to be 2.6 times bigger in 2011 (Economou et al, 2013). Relevant studies in the teaching profession between 1995 and 2015 in Greece have also shown trends in increasing levels of emotional exhaustion and decreasing levels of personal achievement; the two important parameters of occupational exhaustion (Panagopoulos et al, 2016).

The aim of the present work was to investigate teachers’ perceptions on their economic restrains and the possible link between financial hardship and burnout.

The present work was carried out during the school year 2017-18. The aim of this work was to investigate teachers’ perceptions about their economic restrains and the possible link between financial hardship and burnout.

Methodology

The sample is based on Primary School teachers in the city of Arta, NW Greece. The head teachers of 16 Primary Education Schools were informed about the aim of the present work and the survey was distributed in the schools together with a letter informing teachers about their volunteer participation. Of the 155 distributed questionnaires, 125 completed questionnaires were collected (return rate 81%%). The number of the completed questionnaires corresponds to about 23% of the total number of Primary School teachers in the region.

The distributed questionnaire included:

(i) participants’ demographic data, (ii) the Maslach’s Burnout Inventory (MBI) as adopted for usage in Greek language by Kantas (1996) and Kokkinos (2006) is assessing the three dimensions of the burnout syndrome: emotional exhaustion, efficacy and depersonalization, and (iii) the Economic Hardship questionnaire of Barrera et al. (2001) adapted for usage in the Greek language was used to investigate teachers’ perceptions about their economic hardship.

Data was analyzed and tested for normal distribution with SPSS (version 14.01). All parameters exhibited Cronbach’s’ alpha coefficient ≥ 0.71 providing assurances for the internal consistency of the data. Spearman’s correlation was used to estimate the association between economic hardship and burnout dimensions. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the effect of gender, age and teaching work experience on the percentage of teachers with High level of Emotional Exhaustion. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results & Discussion

Teachers’ largest age group (40.8%) was above 50 years old, followed by the age groups of 40-50 (33.6%), 30-40 (18.4%) and only a small fraction (7.2%) were younger than 30 years old.

Most of the teachers had more than 15 years work experience with 48% having >21 years, followed by those with 15-20 yrs (20%), 10-15 years of work experience (16%); 5-10 (7.2%) and 8,8% with less than 5 yrs of teaching experience.

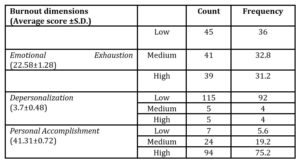

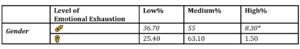

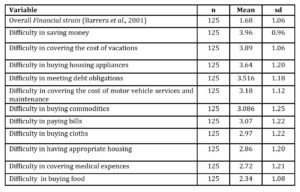

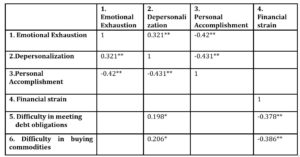

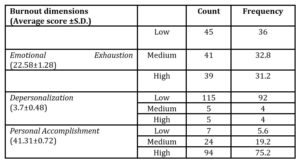

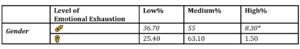

The mean values of MBI Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization and Personal Accomplishment are presented in Table 1 with the scores of each dimension grouped in scores of: low, medium and high level groups (Maslach & Leiter, 1999). These values are similar with previously reported results from teachers in Greece. Research in Greece and in other countries show teachers to have been holding on the positive aspects of their job and maintaining high levels of personal accomplishment and not to exhibit high levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion (Anastasiou, & Papakonstantinou, 2014; Panagopoulos et al. 2015; Skaalvik et al., 2010). In the present work, most teachers exhibited medium / low emotional exhaustion, low depersonalization and high personal accomplishment. These values can be interpreted as a reflection of low burnout of those who participated in the present work. Yet, a small percentage (9.8%) of teachers exhibits high scores of emotional exhaustion. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relation between gender and the percentage of teachers with High level of Emotional Exhaustion (Table 2). The relation between these variables was significant (X2= 4.88, df=1, p=0.027). Men were more likely than women to exhibit high level of emotional exhaustion.

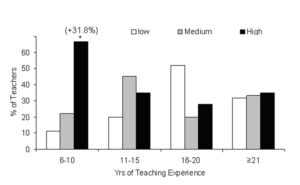

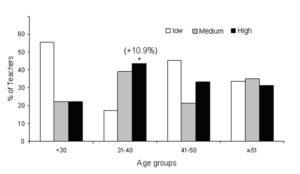

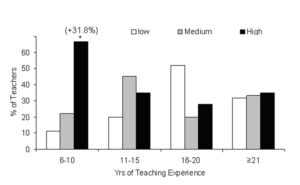

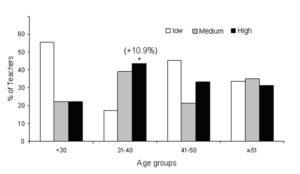

Further analysis of the data indicated that work experience (Figure 1) and age (Figure 2) were related with different levels of emotional exhaustion, whereas there was no difference in the scores of depersonalization and high personal accomplishment.

Economic hardship can be described as psychological distress caused by financial difficulties (Barrera et al., 2001). In this respect, teachers who face financial difficulties may also experience stressful situations in their professional life. For example, a combination of economic difficulties and professional stress can result in emotional exhaustion and can initiate an onset of a cascade of the psychological steps which in turn can lead to depersonalisation (Elit et al., 2004).

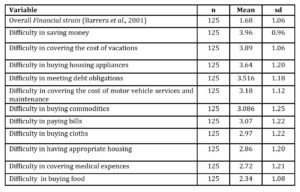

Table 1: Average score and level of burnout in primary school teachers in Arta, Greece

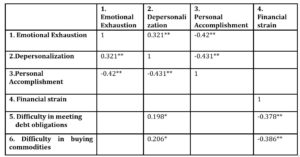

A Pearson correlation analysis between the dimensions of emotional exhaustion and indices of economic hardship: Significant correlations were observed between depersonalisation and emotional exhaustion and between depersonalisation and the difficulty in meeting their financial obligations or buying commodities (Table 4). There was no significant correlation between Economic hardship and the dimensions of emotional exhaustion or of personal accomplishment). The absence of a significant correlation between these mentioned burnout dimensions and financial hardship may reflect the low levels of hardship of the sample and the contribution of other parameters which may affect the possible negative effect of hardship on the dimensions of burnout. For example, job satisfaction and emotional intelligence may have a ‘protective” effect on teachers facing unfavourable working conditions (Anastasiou, 2020) with teachers getting their rewards from the teaching rather than their salaries, a situation historically present in Greece (Anastasiou, & Papakonstantinou, 2014) which results in low burnout levels of teachers in Greece (Kourmousi & Alexopoulos, 2016).

Yet, a significant portion of the teachers exhibited high level of emotional exhaustion according to age and work experience. Compared to younger teachers, those with age >30 yrs old exhibited increased levels with a peak in the age group 30-40.

Work experience also had an impact on emotional exhaustion with a peak in the group with work experience 5-10 yrs. Emotional exhaustion can reflect professional stress and be a precursor of depersonalisation. The high levels of emotional exhaustion exhibited in the teachers who participated in the present work can be a first step prior to depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment (Steinhardt et al., 2011).

Table 2: Frequency distribution of low, medium and high levels of emotional exhaustion of Primary School teachers in Arta, Greece

*Analysis of data with chi-square test indicated a significant gender effect in the group of High emotional exhaustion, but there was no significant gender effect in the groups of Low and Medium level of emotional Exhaustion. Men were more likely than women to exhibit high level of emotional exhaustion (X2= 4.88, df=1, p=0.027).

*Analysis of data with chi-square test indicated a significant gender effect in the group of High emotional exhaustion, but there was no significant gender effect in the groups of Low and Medium level of emotional Exhaustion. Men were more likely than women to exhibit high level of emotional exhaustion (X2= 4.88, df=1, p=0.027).

Fig. 1: The influence of teaching experience on the frequency distribution of low, medium and high levels of emotional exhaustion of Primary School teachers in Arta, Greece. Teachers with 6-10 years of experience, had 31.8% increased presence in the group of high level.

In spite of historically established professional values of teachers and school leaders which shield them against occupational stress (Anastasiou & Papakonstantinou, 2015), some signs of frustration and limited capacity to keep going as before could be the root of high levels of emotional exhaustion exhibited by a group of teachers who participated in the present work.

In Greece, a steady income and job security were historically contributing factors for pursuing a teaching career. The consequences of economic hardship may generate a cascade of events which can lead to decreased job satisfaction and burnout. For example, a reduction in income may have an effect on the job satisfaction of teachers as it affects their perceptions about the recognition of their work (Koutouzis & Malliara, 2017). Consequently, job satisfaction can suffer in the periods of economic recession, rising taxation and salary cuts experienced by teachers in Greece.

Due to the relative small number of teachers and the only one sample, these results should be viewed with caution, nevertheless, further research is required to ensure the initiation of school management actions by school leaders in employing positive actions (Ismail et al, 2019), and if possible financial incentives (Chetty et al., 2014) which could counteract stressful professional conditions and increase the feeling of teachers’ personal accomplishment. The results of the present work provide evidence for the need to monitor the level of burnout in primary school teachers in Greece and if possible explore the possibilities for proactive measures according to modern human resource practices. Further research and policies should be employed to counteract any negative consequences of teachers’ prolonged occupational stress and economic hardship. For example, initiative which can increase the level of teacher’s emotional intelligence may have a protective effect on teachers who are exposed to adverse professional conditions (Fernández-Berrocal et al. 2017; Platsidou, 2010).

Proactive Human resource initiatives and leadership style can also prevent the development of conditions which can lead to burnout (Kruger & Roets, 2013).

School leadership can also have a mediating role on the development of burnout syndrome, by making provisions for the needs of teachers and increasing commitment (Ford et al. 2019; Helou et al. 2016).

Fig. 2: The influence of age on the frequency distribution of low, medium and high levels of emotional exhaustion of Primary School teachers in Arta, Greece. Teachers with age 31-40, had 10.9% increased presence in the group of high level.

Irrespective of any potential benefits expected by management initiatives, school leaders in Greece are unable to modulate the salaries of their teachers or even have a saying on the recruitment and the selection of their teaching staff. School leaders may have already utilised to the maximum of their potential any available human resources management tools to encourage and reward their teachers and create positive atmosphere in their schools. Teachers in Greece experienced ten difficult years with dramatic reduction of their income and challenging working conditions (OECD, 2017) with school merges, changing educational systems, social and technological changes which require commitment and mental and physical resources.

So far, teachers in Greece have been holding on the positive aspects of their job and maintaining high levels of personal accomplishment even when they experience unforeseen financial difficulties which required significant changes and adjustments. The results of a long term financial crisis experienced by public servants in Greece may have created long term consequences. In times of financial crisis, there are changes in the work environment of educational units that may lead to an increase in teachers’ job burnout levels and affect decision-making processes. Emotional exhaustion can reflect professional stress and be a precursor of depersonalisation.

Table 3: Indices of Economic hardship of primary school teachers in Arta, Greece

Table 4: Spearman correlation between burnout dimensions and indices of economic hardship of Teachers in Greece. Only significant correlations are displayed in this table. Asterisks indicate the level of significance of the correlation (*P≤=0.05, **P=≤0.001)

The age group of teachers which exhibited high level of emotional exhaustion is the group which faces a long teaching career until retirement. It is alarming to see high levels of emotional exhaustion of this age group. Emotional exhaustion can reflect professional stress and be a precursor of depersonalisation. Further research and policies should be employed to counteract any negative consequences of teachers’ prolonged occupational stress and economic hardship.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Anastasiou, S., & Papakonstantinou, G. (2014). “Factors affecting job satisfaction, stress and work performance of secondary education teachers in Epirus, NW Greece”. International Journal of Management in Education, 8(1), 37-53.

- Anastasiou, S., Filippidis, K., & Stergiou, K. (2015). Economic recession, austerity and gender inequality at work. Evidence from Greece and other Balkan countries. Procedia Economics and Finance, 24, 41-49.

- Anastasiou, S., & Papakonstantinou, G. (2015). Greek high school teachers’ views on principals’ duties, activities and skills of effective school principals supporting and improving education. International Journal of Management in Education, 9(3), 340-358.

- Abuhashesh, M., Al-Dmour, R. and Masa’deh, R.E., 2019. Factors that affect Employees Job Satisfaction and Performance to Increase Customers’ Satisfactions. Journal of Human Resources Management Research, Vol. 2019, Article ID 354277, DOI: 10.5171/2019.354277 1-23.

- Anastasiou, S (2020). A moderate effect of age on preschool teachers’ Trait Emotional Intelligence in Greece and implications for preschool Human Resources Management. International Journal of Education and Practice, 8(1), 26-36. DOI: 10.18488/journal.61.2020.81.26.36

- Barrera, M., Caples, H. and Tein, J.Y. (2001), “The psychological sense of economic hardship: measurement models, validity, and cross-ethnic equivalence for urban families. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29 (3), pp. 493-517.

- Chelwa, G., Pellicer, M., & Maboshe, M. (2019). Teacher Pay and Educational Outcomes: Evidence from the Rural Hardship Allowance in Zambia. South African Journal of Economics, 87(3), 255-282.

- Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, and Jonah E. Rocko¤. 2014. Measuring the Impacts of Teachers II: Teacher Value-Added and Student Outcomes in Adulthood.American Economic Review, 104(9):2633.79. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.9.2633.

- Crowe, L., Butterworth, P. & Leach, L. (2016). “Financial hardship, mastery and social support: Explaining poor mental health amongst the inadequately employed using data from the HILDA survey”. SSM – Population Health, 2, 407-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.05.002 .

- Economou, M., Madianos, M., Peppou, L. E., Patelakis, A., & Stefanis, C. N. (2013). “Major depression in the era of economic crisis: A replication of a cross-sectional study across Greece”. Journal of Affective Disorders. 145(3), 308-314. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.008

- Elit, L., Trim, K., Mand-Bains, I. H., Sussman, J., & Grunfeld, E. (2004). “Job satisfaction, stress, and burnout among Canadian gynecologic oncologists”. Gynecologic Oncology, 94(1), 134-139.

- Fang, L., Fang, C.L. and Fang, S.H., 2016. Work Stress Symptoms and their Related Factors among Hospital Nurses. JMED Research Vol. 2016 (2016), Article ID 746495, pp.12-s.

- Fernández-Berrocal, P., Gutiérrez-Cobo, M. J., Rodriguez-Corrales, J., & Cabello, R. (2017). Teachers’ affective well-being and teaching experience: the protective role of perceived emotional intelligence. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 2227.

- Filippidis, K., Anastasiou, S., & Mavridis, S. (2014). “Cross country variability in salaries’ changes of teachers across Europe during the economic crisis”. Conference Proceedings: 5th International Conference on International Business (ICIB), University of Macedonia, May 23-25, Thessaloniki, Greece.

- Ford, T. G., Olsen, J., Khojasteh, J., Ware, J., & Urick, A. (2019). The effects of leader support for teacher psychological needs on teacher burnout, commitment, and intent to leave. Journal of Educational Administration.

- Grigoriadis, M., & Klefaras, G (2017). “Depressive Symptomatology, Attachment Style, Job Insecurity and Burnout of Civil Servants in the Greek Economic Crisis. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology, 6(1), 96–112.

- El Helou, M., Nabhani, M., & Bahous, R. (2016). Teachers’ views on causes leading to their burnout. School leadership & management, 36(5), 551-567.

- Hock, R. R. (1988). Professional burnout among public school teachers. Public Personnel Management, 17(2), 167-189.

- Ismail, S. N., Abdullah, A. S., & Abdullah, A. G. K. (2019). The Effect of School Leaders’ Authentic Leadership on Teachers’ Job Stress in the Eastern Part of Peninsular Malaysia. International Journal of Instruction, 12(2), 67-80.

- Jackson, C Kirabo, Jonah E Rocko¤, and Douglas O Staiger. 2014. Teacher Effects and Teacher-Related Policies.. Rev. Econ. 6(1), 801.825.

- Kamtsios, S. (2018). Burnout syndrome and stressors in different stages of teachers professional development: the mediating role of coping strategies. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 15, 229-253.

- Koev, R., Tryfonova, O., Inzhyievska, L., Truskina N., Radieva M. (2019), Management of Domestic Marketing of Service Enterprises”, IBIMA Business Review, Article ID 681709, DOI: 10.5171/2019.681709

- Kokkinos, M. (2000). Professional burnout in Greek primary school teachers: Cross cultural data on the Maslach Burnout Inventory. International Journal of Psychology, 35, pp. 249-254.

- Kourmousi, N., & Alexopoulos, E. C. 2016. Stress sources and manifestations in a nationwide sample of pre-primary, primary, and secondary educators in Greece. Frontiers in public health, 4, 73.

- Koutouzis, M., & Malliara, K. (2017). Teachers’ Job Satisfaction: The Effect of Principal’s Leadership and Decision-Making Style. International Journal of Education, 9(4), 71-89.

- Kruger E, Roets HE. 2013. Guidelines for the management of job related stress amongst secondary school teachers in the Limpopo Province. Online J Edu Res. 2(3), 41-49.

- Leslie, K., & Canwell, A. (2010). Leadership at all levels: Leading public sector organisations in an age of austerity. European Management Journal, 28(4), 297-305.

- Luk, A. L., Chan, B. P., Cheong, S. W., & Ko, S. K. (2010). An exploration of the burnout situation on teachers in two schools in Macau. Social Indicators Research, 95(3), 489-502.

- Maslach C, Leiter M (1999). Burnout and engagement in the workplace. A contextual analysis. Advance in Motivation and Achievement, 11, nn 1-302.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. (2001) Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology. 52:397-422

- Niessen, C., Mäder, I., Stride, C., & Jimmieson, N. L. (2017). Thriving when exhausted: The role of perceived transformational leadership. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 103, 41-51.

- Panagopoulos, N., Anastasiou, S., & Goloni, V. (2014). Professional burnout and job satisfaction among physical education teachers in Greece. Journal of Scientific Research & Reports, 3(3), 1710-1721.

- Panagopoulos, N., Golini, B. & Anastasiou, S. (2016). “The effect of personal – demographic characteristics in occupational exhaustion Primary School Teachers in Achaia”, 2nd National Conference for the promotion of Educational Leadership (in Greek).

- Perrone, F., Player, D., & Youngs, P. (2019). Administrative Climate, Early Career Teacher Burnout, and Turnover. Journal of School Leadership, 29(3), 191-209.

- Platsidou, M. (2010). Trait emotional intelligence of Greek special education teachers in relation to burnout and job satisfaction. School psychology international, 31(1), 60-76

- Rentzou, K. 2012. Examination of work environment factors relating to burnout syndrome of early childhood educators in Greece. Child Care in Practice, 18(2): 165-181.

- Richardson, S., Lester, L., & Zhang, g. (2012). “Are casual and contract terms of employment hazardous for mental health in Australia?”. Journal of Industrial Relations, 54 (2012), pp. 557-578.

- Skaalvik, Einar M., and Sidsel Skaalvik. “Teacher Self-Efficacy and Teacher Burnout: A Study of Relations.” Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies 26, no. 4 (2010): 1059–069.

- Solis-Soto, M. T., Schön, A., Parra, M., & Radon, K. (2019). Associations between effort–reward imbalance and health indicators among school teachers in Chuquisaca, Bolivia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 9(3), e025121.

- Steinhardt, M., Smith-Jaggars, S., Faulk, K., & Gloria, C. (2011). Chronic work stress and depressive symptoms: assessing the mediating role of teacher burnout. Stress and health, 27, pp. 420-429.

- Kantas A. (1996). Το σύνδρομο της επαγγελματικής εξουθένωσης στους εκπαιδευτικούς και εργαζόμενους στα επαγγέλματα υγείας και πρόνοιας. Ψυχολογία, 3, 71-85 (in Greek).

- Kyriacou C. Teacher stress: Directions of future research. Educational Review. 53 (2001): 27-35.

- OECD (2017). Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en

- Stagia, D. & Iordanides G. (2014). Occupational stress and professional burnout among Greek teachers in secondary schools under conditions of economic crisis. Επιστημονική Επετηρίδα Παιδαγωγικού Τμήματος Νηπιαγωγών Πανεπιστημίου Ιωαννίνων, 7, 56-82. (in Greek).