Introduction

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2017), many countries are going through major changes of traditional structures of culture. One example of such a shift is the development of so-called hybrid libraries, defined as libraries in which traditional and non-traditional sources of information and entertainment are merged and integrated.

The term “hybrid” can mean several things in a library context other than that of the hybrid library. The term has been used, for example, relating to hybrid library professionals (i.e., possessing several skill sets), libraries that combine an academic and corporate purpose or a library and museum’s purpose, the use of hybrid instruction methods (e.g., online and face to face), or a library that combines public and private spaces (e.g., a library and a theatre), reactions of libraries to hybrid open access (e.g., article processing charges or not), and hybrid professionals (combining different skill sets).

The idea of the concept of hybrid libraries was developed in the United Kingdom (UK), as “a worthwhile model in its own right, which can be usefully developed and improved” (Pinfield et al., 1998). The term hybrid library was first mentioned in The Builder Project, started in 1998, at the University of Birmingham, UK, for the development of hybrid libraries (Pinfield and Mckenna, 1998). The concept of hybrid libraries, in the course of the project, referred to that hybridity found where the traditional library could be run alongside electronics, and where the services and resources of each were integrated.

As Fowke (2019) states, hybrid libraries can be considered as institutions that combine characteristics of public institutions and private associations. In addition, the tangible goods and services that these libraries offer to potential members combine internet technology, social media, and print resources. Imo and Igbo (2019) state that hybridity starts in a library when the institution adopts electronic information sourcing, cataloguing and indexing, with an emphasis on automatic indexing, abstracting, website design, and on the mechanics of search engines and internet surfing. For this, the library promotes information literacy skills and user education for adapting to the electronic environment.

The hybrid library is “a mixed entity, where traditional documents, digital information and services offered in the facilities of the library coexist with other services offered online” (Orera-Orera, 2007, p. 30). Hybrid libraries require librarians to adopt new roles in information quality control and information management (Orera-Orera, 2007). However, Barajas and Alfonso Sánchez (2005, p. 12) claim that “the motivation behind the concept of hybrid library is the need to deal with diversity, which is an important issue when libraries advocate for a world where the information is globalized”.

Scotland is a part of the United Kingdom where the concept of hybrid libraries was founded, whilst in Brazil, hybrid libraries are still emerging (Silva, 2017). Scotland’s public libraries are part of a shared civic ambition to fulfil the potential of individuals and communities, promoting six strategic aims: reading, literacy and learning; digital inclusion; economic wellbeing; social wellbeing; culture and creativity; and excellent public services (The Scottish Government et al., 2015). In Brazil, many libraries describe themselves as hybrid (Congresso Brasileiro de Biblioteconomia, Documentação e Ciência da Informação, 2017), highlighting that they act as living organisms, which constantly change to help in the development of society by means of actions that lead individuals who use these libraries, as well as their environments, to growth and development. “Hybridity” in Brazilian libraries is used in a different way from Scotland, because in Brazil, they consider hybridity to be a new form of use of technology (Silva, 2017). Hybridity is not always applied according to the concepts previously defined in librarianship (as used by, e.g., Suseela, 2016), perhaps because of the lack of financial resources available to those institutions, which intend to become hybrid.

This article aims to study hybridity within Brazilian and Scottish public libraries, understanding that the management of these libraries is controlled in different ways, because of the fact that the economic and political backgrounds of the two countries are very different. This research sought to answer three questions, i.e., “what are the necessary components of a hybrid library?”, “what are the approaches of developing hybrid environments in public libraries?” and “how are hybrid public libraries managed in the two countries?”. The preference for public hybrid libraries was because the concept of hybrid library has been longer developed in university libraries, so the authors of this research are trying to understand how this occurs in other types of libraries.

The libraries studied in Brazil were Sao Paulo Library (BSP), and Parque Villa-Lobos Library (BVL). In Scotland, the libraries studied were the Central Library of Dundee, and the Central Library of Aberdeen. The authors tried to understand the similarities and differences between these two cultures. The study was carried out in 2016. The authors examined the products and services offered in the processes with their community and the proposed hybridity of each institution. Due to COVID-19, it has not been possible to bring the results up to date; however, some thoughts and speculations about the impact of COVID-19 have been included in the Discussion.

Methods

The authors of this paper carried out an on-site survey, personally visited and observed the case study libraries, and conducted interviews in the libraries. In this way, they explored their sample of Brazilian and Scottish hybrid libraries and examined information management and community development in these places. In collective or multiple case studies, data collection needs to be flexible enough to allow a detailed description of each individual case to be developed, considering the emerging similarities and differences in cross-case comparisons (Yin, 2009).

This research was a qualitative, descriptive-exploratory and comparative study to examine the state of public hybrid libraries in the two countries. The choice of the qualitative approach was based on the objectives set for the development of the study, namely the observation of the relations between individuals and hybrid environments. This study is descriptive-exploratory because it obtained information about the research universe based on data collection and the use of analysis instruments through on-site observations.

Content Analysis (Gorman and Clayton, 2005) was used to establish the basic categories to explore data identified by the literature review about the similarities and differences between the hybridity concept and the structural environment of public libraries. The Content analysis was conducted manually, and the pre-established categorisation identified the aspects that characterised hybrid libraries and their way of acting in the public sphere.

Based on the literature review, the indicators that guided the interviews in both countries were: 1) users’ and librarians’ ability of understanding the characteristics of social changes; 2) employees’ and users’ training on the use of hybrid libraries to adapt them to this context; 3) social inclusion actions; 4) the interaction between technology, the physical structure and the human character; 5) community development actions; and 6) accessibility.

These indicators are considered the base to the Findings and Discussions section. The first indicator meets the need for understanding the social demands, and adapting behaviours to them. The second indicator is the practical part of this project, namely working with employees and users’ abilities in order to make them familiar with the new services and products offered by the library. The third indicator refers to the libraries’ actions in favour of making all citizens part of their communities. This indicator is also related to the fifth indicator, showing the activities carried out by the library to develop its community, including users, librarians, employees, and possible other users. It is also related to the sixth indicator, which works with all types of technology needed to include people who need special materials to access the information registered in the libraries – an example for this is the letter amplifiers machines for people with low vision. The fourth indicator represents the base of the concept, working in line with technology to provide the society with access to the maximum amount of information.

Thanks to the funding given for this research, one of the authors was able to visit Scotland (da Silva), and so the two target areas chosen for the study (part of Brazil, and part of Scotland) formed a convenient sample for cross cultural research that can hopefully represent the approaches to hybrid libraries in the UK and Brazil. The authors selected the libraries that were approached because, in their judgement, they are important for the cultural and economic development of their localities, and because they are known internationally due to their design. In the case of BSP and BVL, they are known internationally because of their design. The Central Library of Dundee is one of the most proactive institutions regarding social inclusions and assistance for disabled people. Located in a university city where different cultures from various countries are living together, The Central Library of Aberdeen provides its services to meet the needs of a large local population.

In this research, interviews (Appendix A), participative observations (Appendix B) and questionnaires were conducted. In the initial data collection phase, interviews and observations were carried out on the basis of the comments of (Pinfield et al., 1999 & Oppenheim and Smithson, 1999). The development of the resulting content analysis indicators formed part of the interview, as well as the elaboration of the items that would be analysed during the observation.

The interviewees were the director librarians of the libraries chosen. A basic questionnaire was carried out, with 16 questions developed to explore the hybrid libraries, as well as the categories of information management and social inclusion, in order to understand the professional performance, the institutional management, the community development, and the users in the library. The questions were developed from the literature of hybridity covered by this research. The interviews were recorded, and the data collected was fully transcribed, but only the parts released by the interviewees were published.

The questions for the interviewees approached were about the following aspects: 1. The nature of the library, 2. The provision of network access for users, 3. The forms of borrowing items, 4. The charges for services, 5. The specific local materials, 6. Material support in the library, 7. The provision of user training, 8. The forms of user training, 9. The library’s web presence, 10. Events promoted by the library, 11. The library’s annual report, 12. The interaction between the library and its community, 13. The interaction between the library and other libraries, 14. Participation in networks, 15. Free/charge services, and 16. Any other relevant information. The observations focused on the physical structure (furniture, architecture, signalling, location), machinery (available services, material storage, partitions, special spaces, differentiated design, wi-fi, location of research devices, collection, layout of materials, architecture of the environment) and accessibility (elevators, ramps, spaces between corridors, special equipment).

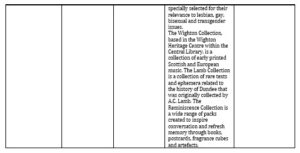

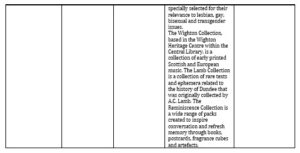

The Scottish libraries studied

The Central Library of Dundee is responsible for the ‘Leisure and Culture Dundee’ part of the local government. Being a part of the wider community, the library has strong links with culture, sport and leisure, which brings opportunities for joint projects, working closely with Dundee City Council and other agencies including social work, early years, education, cancer support and the Department for Work and Pensions. The general collections available in Dundee libraries, at the time of this study, were as follows: adult fiction (92,900 items); adult non-fiction (80,129 items); and reference stock. Most of the stock is available for loan; however, it also holds reference material. Examples for this include the Local Studies department, which entirely consists of references only. Newer acquisitions are included in the online catalogue whilst older items are searchable via a card index. The collection also includes children’s fiction (71,373 items); children’s non-fiction (55,672 items); teenage/young adult collection (7,728 items); graphic novels and manga (3,561 items); DVDs (9,153 items – comprising sub-collections of new releases, back catalogues, boxed sets, educational, children’s, cinema); adult audio books collection (8,233 items); children’s audio books collection (1,435 items); large print collection (11,609 items); CD collection (6,757 items); periodicals collection (the main periodical collection is held in Reference & Information, but the library has small collections of online magazines via its Zinio service and access to over 17,000 comic, graphic novel and manga downloaded via Comic Plus service); and project collections (the School Library Service provides Dundee teaching staff with access to topic boxes containing books and artifacts to support project work in schools). Local studies also provide reference access to project folders of cuttings and information on prominent local topics such as whaling or jute mills (Scottish Library and Information Council, 2020).

The Central Library of Aberdeen, created in June 1892, offers public access PCs for 51 adults plus eight for children. Information resources include books and online resources. Adult books, children’s books, talking books, CDs, DVDs, videos, language courses and toys are all available for loan. There is an Online Public Access Catalogue (OPAC), and free access to the Internet, email, Wi-Fi, as well as Microsoft Office on library PCs. A scanner, adaptive technologies, a photocopier and a fax machine are also available in the library. The library offers storytelling sessions, regular school visits, bookbug sessions and School Holiday Programmes. Specialist services include Business Information, a Local Studies Library, a Community Reference Library, Europe Direct Aberdeen, newspapers and periodicals. The library organizes exhibitions and events, a Careers Information Point, a Migrant Information Point, Special Collections, and a Café. The library works with both public and private sector organisations, and charitable institutions. The library works together with the Aberdeen Council of Voluntary Organisations (ACVO) (www.acvo.org.uk), local universities, and Aberdeen Shared Libraries. The library is a member of the Scottish Library and Information Council (SLIC), recommending national strategies and plans for Scottish libraries (Scottish Library and Information Council, 2020).

The Brazilian public libraries studied

The BSP was inaugurated in 2010, with the aim of encouraging and promoting reading. It is located in the North Zone of Sao Paulo. Its structure was designed to offer comfort, autonomy and attention to its patrons. It occupies an area of 4,257 square meters, divided between the ground floor, and the upper floor for children, youth, adults and elderly people with and without disabilities. The library has technological resources, offering its users computers, wireless network and self-service terminals. The core team of the institution is composed of 12 employees, divided between a Library Director, an Operational Manager, a Manager of Collection and Technical Treatment Center, a Cultural Production and Programming Manager, a Social Work Coordinator, a Coordinator, and six Service Leaders. In 2016, the institution reached an average of 302,391 users, with 29,931 active members, 2,032 acquisitions, 133,158 consultations and loans, and 22,405 participations in cultural actions (Biblioteca de São Paulo, 2020).

The BVL, also inaugurated in 2010, occupies an area of 4,000 square meters inside the Villa-Lobos Park, West Zone of Sao Paulo. The collection, constantly updated, focuses on literature and environmental issues. It is made up of books, magazines, newspapers, electronic books, audiobooks, comics, DVDs and CDs, as well as Braille and spoken books aimed at people with disabilities. Its core team is made up of 12 employees, divided as in the BSP. In 2016, it had an average attendance of 243,398 people, with 26,610 active members, 140,004 consultations and loans, and 25,362 participations in cultural actions (Biblioteca Parque Villa-Lobos, 2020).

Findings and discussions of the results

The study aimed at identifying some necessary elements to be present in hybrid libraries, and showing the differences between public hybrid libraries in Brazil and Scotland. These elements, which are considered to be essential for a library to be characterised as hybrid, are developed further in this paper. These elements include: 1) future improvement; 2) employees; 3) users; 4) collection; 5) internal design; 6) external design; 7) local information management; and 8) external information management. It is important to also highlight employees’ training, career development, and lifelong education. In addition, the library needs to conduct training for users, and offer services that involve the whole community, along with lifelong education. The nature of the collection, its sharing, the informational support offered, the forms of acquisitions, and the free of charge access to databases should be also taken into account.

When looking at the internal design, namely, the design of the library building (the library interior), the possibilities of social inclusion must be given priority, including local infrastructure, special spaces, and accessibility to the public. On the other hand, for the external design, the local information architecture in relation to the library’s partnership and community has to be considered.

Local information management involves the development of events, activity plans and main objectives, as well as focusing on each service offered by the library. Regarding the management of external information (or the information acquired by the society and other institutions, outside the internal environment of the library, but that interferes in its internal work), it was observed whether the libraries worked together with other libraries or organisations, public or private, in order to promote an information network. However, these characteristics are developed differently in Brazil and Scotland.

The Brazilian public library environments studied improve access and users’ services, helping the disadvantaged sections of the population; work with public and private companies and government actions for promoting libraries and social inclusion; promote teamwork and the development of a network of professionals from various fields, who work with the different needs of users; and interact with national and international cultural facilities. Public hybrid libraries have the potential to develop new attitudes and concepts of information dissemination.

Based on this analysis, it was understood that a local hybrid library in Brazil has to be available to the general community – teachers, students, social managers and stakeholders in social management; works with organisations in the area where the library is active; supports the development of local innovations capable of promoting networks of socio-productive systems and the economy; develops new social technologies and shares them with other institutions and/or organisations that provide spaces to support social management. It should emphasise the functions of access and pay attention to the public, and in particular, the less favoured social strata.

One of the Brazilian hybrid libraries’ management objectives is to develop collaborative agreements with governmental and non-governmental institutions. A bold design is increasingly important to them, as well as the promotion of links with renowned institutions at the national and international level to support the cultural outputs produced by society.

Scotland’s libraries are active in offering school holiday programmes, business information, local studies materials, community reference content, provision for users at all levels, home services, information for recent immigrants, special collections, cafés and mentors, who offer one-to-one appointments, helping users to develop their own approach to particular research. The hybrid libraries work with teaching sessions, developing and using, in response to users’ feedback, a range of innovative practices to enhance these sessions, drawing on best practice within the sector, reviewing programmes, teaching practices, and developing programmes that recognise the diversity of their users. These approaches are recommended for Brazilian public libraries in the future.

The authors have categorised the findings of the research into Brazilian and Scottish public hybrid libraries, in order to analyse users’ and librarians’ understanding of the characteristics of social changes; their training on the use of hybrid libraries to adapt them to this context; social inclusion actions; the interaction between technology, the physical structure and humans; community development actions; and accessibility. These are explored in the next two subsections.

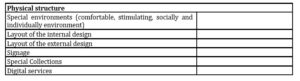

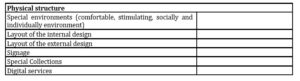

Table 1 shows all the indicators discussed and all the libraries studied.

Table 1: Content analysis indicators in the libraries studied

Source: Created by authors.

All the relevant indicators were noted once or many times in the Brazilian public hybrid libraries studied. These social aspects presented here are different than the previous literature, where the concept of the hybrid library was more focused on the convergence of technology rather than the needs of local users.

In the interviews conducted in the BSP, the available resources, the organisation of the collections, services, products, different environments, and accessibility methods were shown. The Human Resources Department provided, represented by their social worker, spoke about the sociocultural approach that the library has adopted for its community.

The Programming Department explained the libraries’ projects. The Technical Department (librarians) talked about the institutional concept of users and living libraries, employee training, interconnected management (SP Reading Project), and the institutional philosophy. It is important to say that all the programmes that the BSP has (the first library of the SP Reading Program) were also applied in the BVL – the only change is the availability of the collection in the physical structure of the library.

From the perspective of Scotland, all the indicators were also present in the Scottish libraries studied. Scottish libraries are working with social aspects, which is, again, differing from the previous literature of hybrid libraries.

As for the interview with the Central Library of Dundee, the librarian was surprised when told that the research was about hybrid libraries. This is because she understands that all libraries in the UK are hybrid, and that being hybrid is the norm in these libraries. This supports the authors’ assertion that for many UK librarians, the term “hybrid” is meaningless, as it has become absorbed into the perception for all libraries. Dundee Central Library is a hybrid library, because it not only provides printed and digital media, but it also offers inclusion for all people of different social classes, disabilities, and different ages including students, postgraduates, etc. The library provides professionals specialized in different areas to serve its users (indicator “users’ and librarians’ ability of visibility and understanding the characteristics of social changes”).

The librarian of the Central Library of Aberdeen understood hybridity as the convergence of community, library and technology. In this way, the library tries to be an information centre, adapting its services according to the changes of its community, e.g., acquiring new materials for new residents of the city who speak a native language different than English.

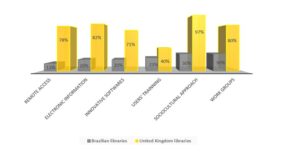

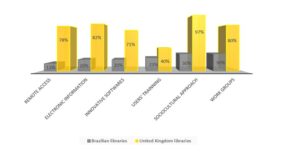

Figure 1 illustrates the comparison referenced between the Brazilian hybrid libraries and the hybrid libraries of the UK. The tabulation was derived from the mean of the data obtained for each item in the data collection.

Fig. 1. Comparison between Brazilian and United Kingdom hybrid public libraries

Source: Adapted from Silva (2017).

It has been found that the development of hybrid libraries of the United Kingdom is significantly more advanced than observed in the Brazilian context. It can be understood that this difference is due to the several factors that facilitate the possibility of implementing 100% hybridity indicators. Perhaps, such implications include financial investment, the implementation of public policies, and the networking of professionals of other natures in the library.

However, given the perception of differences in the indexes between libraries in Brazil and the United Kingdom, there is that Brazilian concern regarding the transformation of public libraries into hybrids. The indices that stand out most in the Brazilian hybrid process are: the socio-cultural approach and the work groups, in parallel. The same is seen in the libraries of the UK.

The further development of the sociocultural approach indicator (97%) in the UK stems from the already consolidated digital inclusion scenario, which allows library services to focus on users, and does not, in most cases, use digital inclusion strategies.

On the other hand, including user access digitally to remote information sources is low in Brazilian libraries (13%). Due to the large number of printed materials in UK libraries, the lack of space and the need to relocate materials, most of these libraries do not buy printed materials, and instead, digitize all the printed materials they have. So, in contrast, the greatest Brazilian index (sociocultural approach) also collaborates with its lowest level (user training), since the population has a digital inclusion training that can be undertaken in this area, ending up being superfluous, in a British culture.

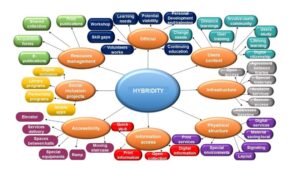

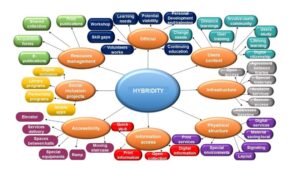

Based on these findings, a model to describe hybrid libraries was developed (see Figure 2 below).

Fig. 2. Organizational environment of public hybrid libraries

Source: Created by authors.

In the model, the term “remote access” ranges from the forms of renewing the items borrowed (by internet, by telephone etc.) via forms of credit of resources (online, via telephone, in person) to the processes of digitization of the analog collection. The system electronically checks the legal requirements (online databases, e-books) and how it is made available by the libraries. It also covers the promotion of institutional information on websites and social networks, and the development of virtual libraries.

“Innovative software” is focused on data management software developed by the library, accessibility software for the visually impaired (with a view for promoting new ways of reading for the visually impaired), popular entertainment software, and software for printing 3D and/or playful materials for the signage and the design of the library. “User training” deals with the forms that a library uses to integrate the users of the services offered by the institution including: training, on-call duty, updates, workshops, lectures and group or individual attendance.

The sociocultural approach is the process in which libraries insert its users in its environment, as well as in society, providing information literacy, as well as conditions for assertive information in relation to the informational needs of users. This information needs to be accessed in a way that favors the generation and sharing of knowledge in society, so the effective participation of users in society. An example is the rehabilitation of users in situations of risk, and users of public agencies. This resocialization involves projects of reading mediation; sharing of stories; philosophical discussions; writing services; cultural workshops; activities for the recognition of the spaces, resources and services offered by the library; the participation of the library in local political activities; as well as the participation in the decision making of the institution. In this line of thinking, the working groups are linked to the division of activities by categories (children, young people and old people) and to the participation of other institutions in the programs of the library (partnerships between public and private companies and the library).

The librarian has to have a clear vision as why and how services are provided; be accountable for the use of resources; think about services from the user’s point of view; provide the services people want; improve access, including physical access to buildings; make services easy to use; develop non-user awareness; and learn from bookshops. Hybrid libraries can serve education, recreation, information and culture. The librarian must choose the public library’s overall mission and role to adopt the suitable strategies for it, and determine the target groups of the library service, without ignoring the general library users.

The library’s role in recreation and personal development includes personal creativity and the pursuit of new interests; access to knowledge and works of imagination; basic education; awareness and life skills, relating to aspects such as health, literacy and jobs; and users’ education. In the areas of culture and arts, the role of the library is achieved by providing a focus on the cultural and artistic development in the community, helping to shape and support its cultural identity and reflecting the cultural variety in the community, such as the language spoken and the cultural traditions. The public library’s social roles are reflected by as acting as a public space and a meeting spot, providing opportunities for informal contact, providing a positive social experience that can contribute to an individual’s feeling of well-being and its contribution to social inclusion.

The results of this research have implications related to the current situation in 2020, where, due to Covid-19, people are socially isolated. A lot of people have lost their jobs; their daily lives have changed in many ways, and governments need to protect the health of their citizens. Information, especially health-related, has become more important than ever. In particular, people need to access reliable sources to be informed about the uncertain world in which they are living. From this perspective, and within the pandemic context, libraries, being institutions that promote information access, started to reinvent themselves to make use of the current social isolation as an opportunity to offer new products and services to society. The authors of this paper focused their attention on the word “reliable”. Misleading information and claims about COVID-19 are circulating everywhere on social media, blogs and web sites. Hence, public libraries, now, have a crucial role to improve information literacy – the ability to distinguish what is reliable information and what is not.

Hybridity in public libraries can assist in the remote linking between libraries and their users, contributing to the computerization of the population at the time of COVID-19. Hence, if access to information is essential to community development, products and services offered by libraries must be rethought. Hybrid libraries can bring benefits to society because, beyond the access to reliable information, the process contributes to the development of entertainment activities, which distract users, even for a while, from the worries caused by the pandemic. Therefore, it is important that libraries ensure that their activities continue functioning remotely, collaborating with other agencies to keep society both informed and entertained.

Conclusions

In the interactive and supportive environment of hybrid libraries of both Brazil and Scotland, individuals are comfortably developing a culture of knowledge, involving the whole information system, and constructing a relationship between data, information and knowledge. Places that have active hybrid libraries both reflect and influence the development of their communities.

It is possible to perceive key differences between the countries. Brazilian libraries focus on products and services, the promotion of online libraries, map environments, photo galleries, extensive activities, social radio projects, projects of public utility, press rooms, research, and investigation. Furthermore, these libraries develop activities such as story time; sensory games; games that promote creativity, initiation and stimulation of cognitive power; reading clubs; board games; monthly exchange with some writers; and access to reading for people with mobility, vision and/or hearing difficulties.

Scottish libraries, in contrast, focus on centers for research collections, and view hybridity as a convergence of digital and printed services, promoting study spaces, exhibition galleries, library helpdesk, online collections, print collections, access to online journals, wireless network, photocopying, printing, scanning, training, mobile device clinic, keeping systems up to date, e-publications, print publications, collection to assist those with all types of disabilities, remote access, special materials, agreement between libraries and organisations, open access resources, workshops to identify the key themes to be explored, and analysis of the skills of the staff, as well as events like story time and sensory games. In practice, these libraries also provide solutions to learning needs, evaluation of information sources, information literacy, personal development, career development, continuing education, volunteer work, distance learning, and digital citizenship, by introducing the concept of print and web searching.

Whilst the Scottish libraries studied are involved in library networks that work together, the Brazilian libraries tended to work in isolation. In the authors’ view, this lack of networks is a major cause of the poor development of Brazilian public hybrid libraries. By working together, Scotland’s libraries gain the strength to achieve their goals as they use their human, material, and financial resources to reach the goal. On the other hand, when an institution works alone, it depends on locating its own resources to reach a goal, and this naturally affects the quality and time of the production of a service.

It is important to consider this research in light of its limitations. The small sample examined may not be typical of all libraries in the UK or Brazil. A further limitation of the study is that it relates specifically to public libraries, and does not include, for example, universities, schools or special libraries. Furthermore, this study has not considered other countries, which may show very different results. Nonetheless, some intriguing similarities and differences have been identified in approaches to public libraries amongst the case study libraries. Finally, the authors recommend that future research could seek to both expand the number of libraries studied, and explore library professionals’ understanding of the role of hybridity in public libraries, as well as their awareness of the implicit factors, which influence the concept of hybrid libraries.

Acknowledgment

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) – Number 2016/10683-6.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Biblioteca de São Paulo, (2020), “Sobre,’ BSP. [Online], [Retrieved August 20, 2020], bibliotecadesaopaulo.org.br/

- Biblioteca Parque Villa-Lobos., (2020), “Sobre,’ BVL. [Online], [Retrieved August 20, 2020], bvl.org.br/h

- Congresso Brasileiro de Biblioteconomia, Documentação e Ciência da Informação, (2017), “Trabalhos,’ FEBAB. [Online], [Retrieved December 12, 2017], www.cbbd2017.com

- Fowke, G. (2019) ‘Librarians before congress: advocacy and identity,’ Legal Reference Services Quarterly, 37(3-4).

- Gorman, G E. and Clayton, P. (2005) Qualitative Research for the Information Professional, Facet, London.

- Imo, N T, and Igbo, U H. (2005), ‘Providing Access to Knowledge in Africa: the need for capacity building in classification, indexing & abstracting skills’ Proceedings of the 1th International Conference on African Digital Libraries and Archives, Ababa, Etiópia.

- Oppenheim, C. and Smithson, D. (1999), ‘What is the hybrid library?,’ Journal of Information Science, 25(2).

- Orera-Orera, L. (2007), ‘La biblioteca universitaria ante el nuevo modelo social y educativo,’ El Profesional de la Información, 16(4), 329-337.

- Pinfield, S. and Mckenna, B. (1998), ‘The Builder Project,’ Electronic Library, 16(5).

- Pinfield, S., Russell, R., Eaton, J., Wissenburg, A., Edwards, C. and Wynne, P. (1998), ‘Realizing the hybrid library,’ D-lib Magazine, 5(10).

- Scottish Library and Information Council, (2020), [Retrieved January 13, 2020], https://scottishlibraries.org/advice-guidance/national-strategies/the-national-strategy-for-public-libraries/.

- Silva, R C. (2017) Gestão de bibliotecas públicas no contexto híbrido: um estudo comparativo de bibliotecas híbridas no âmbito nacional e internacional em prol do desenvolvimento de comunidades, UNESP, Marilia.

- Suseela, V J. (2016), ‘E-commerce trends in the dissemination of scholarly information: impact on hybrid and digital libraries in India,’ International Journal of Information Dissemination and Technology, 6(2).

- The Scottish Government, COSLA, Scottish Library and Information Council and Carnegie Trust (2015) Ambition & opportunity: a strategy for public libraries in Scotland 2015-2020, SLIC,

- United Nations Educational and Scientific and Cultural Organization (2017) Cultura e desenvolvimento no Brasil, UNESCO, Distrito Federal.

- Villa Barajas, H. and Alfonso Sánchez, I R. (2005), ‘Biblioteca híbrida: el bibliotecario en medio del tránsito de lo tradicional a lo moderno,’ ACIMED, 13(2), 2005.

- Yin, R K. (2009) Case study research: design and methods, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Appendix A – Questions for interviewees

- What is the nature of your library collections? Subjects covered/statistics (e.g., number of monographs, number of journals subscribed to, number of visitors, number of Web accesses, number of professionally qualified staff, etc.).

- Do you provide network access for remote users?

- Who is entitled to use your services/borrow items? Just registered users/walk in users/anyone?

- Do you charge for any of your services? (E.g., printing, scanning and/or photocopying – and is that self-service or staffed?)

- Any specific local studies materials/services available?

- What formats are available in your library? (Print/microform/CD/DVD/online access, etc.).

- Do you provide user training? If so, on what topics (E.g., using the library, searching for information, use of social media, evaluating results, etc.).

- How is the user training carried out? (E.g., seminars, workshops, one-to-one sessions, distance learning, YouTube, etc.).

- Does the library have a web presence? Facebook page? Twitter presence? Blog?

- Does the library run events? If so, how often? Does it have a newsletter? Does it provide user guides and other educational material?

- Does the library produce an annual report?

- How does the library interact with its local community?

- How does the library interact with other libraries? With local organisations? With corporations and businesses?

- Is the library part of a network of libraries that assist each other?

- Is free/charged Wi-Fi available in the library?

- I would be grateful if you could give me copies of any guides or other publications relevant to my study and/or the URLs of relevant Web resources.

Appendix B – Comparative table of public hybrid library

The table below was used for a participative observation in the public hybrid libraries. These issues were decided upon by the derivation of the questions made for the interview, and from highlighting what the literature, covered in this study, claimed to be necessary for a library to be considered hybrid.