Introduction

Financial education allows one to understand how money is managed, to identify which decisions to make regarding personal finances and to be informed in order to reduce the risk of indebtedness. Therefore, economic-financial education in basic education institutions worldwide is necessary to allow children to understand the economic world in which they will develop in the future (Cruz, 2018).

In Peru, young people are not confident that they can manage their financial lives due to the low levels of financial inclusion they identify with. According to Avilés et al. (2017), without the formal use of a good or service, it is not possible to have enough savings to invest in education, remodel a house, or, perhaps, grow a business.

The limited knowledge, lack of skills, or distrust in a financial system is what prevents the development of financial inclusion in an individual’s daily life since it generally leads to poor financial decision-making. The Encuesta Nacional de Demanda de Servicios Financieros y Nivel de Cultura Financiera en el Perú en el año 2019 (2019 National Survey on the Demand for Financial Services and Level of Financial Culture in Peru) states that approximately 66% of the Peruvian population saves in some way. Only 70% of young people over 25 years old are known to save, while 49% of young people between 18 and 24 years old are known not to save; in addition, it is also known that 55% of Peruvians who save do so out of the financial system. (Zarate et al., 2021).

The city of Lima, the capital of Peru, is divided into 4 zones, one of them is Northern Lima where 7 private universities have started the operation of their campuses in the last 15 years, due to the important economic growth of the place and the entrepreneurship shown by its inhabitants (López-Guzmán et al., 2019). Based on the above, the general problem of this research is to know. What is the level of financial education of students of a private university in Lima, the capital of Peru, who have already received formal instruction in topics related to finance?

Not knowing the elements that make up financial education, as well as the essential concepts for selecting and managing financial products, results in people not making the best decisions regarding how much to save, what debts to have or what to invest in, which often leads to harming family members or friends as a final trigger. For this reason, governments, private entities, and societies are urged to seek ways to increase awareness and training efforts for new individuals within a financial system (Salazar-Rebaza et al, 2022; Raccanello and Guzman, 2014; Kim et al., 2021; Kaiser et al., 2020).

For citizens, the free choice of buying a product, meeting their obligations as customers of a financial system, or having the possibility of reducing indebtedness are the key to obtaining the desired financial freedom (Goyal and Kumar, 2021; Vanegas et al. 2020; Saxunova et al., 2022). Financial freedom begins with adequate personal financial planning that takes into account not spending more than the amount earned, being aware of the goals or objectives to be achieved, knowing the risks if you want to invest, etc. In other words, the first aspect to be taken into account should be the preparation of a budget to have an efficient frame of reference that allows adequate decision-making (Villada et al., 2018; Villada et al., 2017; Lusardi, 2019).

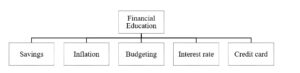

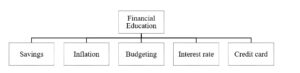

Economic-financial topics should be incorporated since childhood within the curricula of educational institutions, with subjects related to personal finance taught by teachers trained in topics such as savings, budgeting, inflation, credit card management, or interest rate calculation, in order to promote a culture of savings and/or understanding of the economic system that operates in a certain country (Vargas and Avendaño, 2014; López, 2021; Copaja and Alvarón, 2019).

In this sense, it is important to know some concepts with which the individual identifies the 5 dimensions above mentioned, see Figure 1.

The first dimension: savings is the percentage of money that an individual does not spend or invest; it is one of the most important financial elements that an individual can achieve from his/her youth to adulthood through conscious and adequate planning and economic advice (Assusa et al., 2019; Guerrero et al., 2018).

The second dimension: inflation is the increase in the prices of goods in a market within a period. Central banks try to ensure that there is inflation, but on a reduced scale of 2 to 3 percent because, if there is no inflation, an opposite phenomenon called deflation would occur, which would cause prices to fall and this would slow down the process of consumption and economic growth in a country (Chiquiar and Ibarra, 2020; Ribeiro, 2019).

The third dimension: the budget is the set of expenses and income expected for a certain period; it is a plan of action aimed at meeting a specific objective; it is used for personal, family, or institutional purposes. Preparing a budget allows organizations to establish priorities and adapt their management to meet their objectives (Arango et al., 2015).

The fourth dimension: the interest rate is the amount of money that corresponds to a percentage of a transaction. In the case of a deposit, the interest rate corresponds to the money that a person or organization receives for making that deposit available to another one. In the case of a loan, the interest rate expresses the money that must be paid for the use of that loan (Pérez et al., 2021).

The fifth dimension: the credit card is a means of payment that allows making purchases and paying later. The borrowed money is granted by a financial entity and is not harmful if used properly. On the contrary, if the credit is paid on time, it creates a healthy credit profile (Castro, 2014).

Fig. 1. Variable and its dimensions

Although there is a precedent of financial education, it is very clear that this is lacking. Individuals who have never received training in financial topics generally find it difficult to become aware of the need to learn and master these topics regardless of their social class or the country where they live (Salazar-Rebaza et al., 2022).

In their article, Vargas and Avendaño (2014), in Colombia, proposed the creation of a useful instrument to measure the level of basic skills in economics and finance in young people over 15 years old, since the existing instruments were efficient for measuring knowledge but weak in their scope for measuring skills to make better decisions.

On the other hand, Orozco et al. (2016) applied a research study with undergraduate students of the Universidad del Quindío, in Colombia, where it is evident that there is still no mastery of basic financial concepts, perhaps because it is not yet defined as a basic skill that a professional should have. In this sense, actions should be taken and implemented by the institutions since a financially educated person will be less likely to fail.

Likewise, Tinoco (2018) indicates that the students interviewed in Junin, Peru, do not know what a financial product is since they learned to manage their money at home or due to necessity. In addition, they have little knowledge of risk and caution regarding financial entities since the type of credit they usually request is based on their financial need at that moment, and the type of credit that most university students (51, 65%) resort to is the credit card.

According to the findings by Gutiérrez and Delgadillo (2018), in the study conducted at the Universidad Católica Boliviana (Bolivian Catholic University), in Bolivia, 400 university students in the first semester of economic and business science degrees showed that their general knowledge of financial topics is in a medium to a low level, because too many deficiencies are evident. They do not have a long-term vision, despite being aware that participating in a financial education program can improve their level of finances. This factor is repeated in Latin American countries such as Colombia, Brazil, Chile, and Argentina, where it is considered that most young people do not have enough clarity on basic financial topics; however, most of them understand that it is essential to contribute to their financial education and promote its responsible use.

Later, Moreno et al. (2017) concluded in their research in Mexico that students in the last semester of the business degree program do not know how to calculate interest rates. Within the inflation variable, the valuation of money is not considered, so they do not protect their savings. Regarding savings, they are not used to save money to have economic security. Regarding credit cards, they only consider the cancellation for disuse and the reasons why they have ever chosen a credit card. This evidence shows that the population studied does not have sufficient skills to manage financial instruments, even though they have the habit of preparing budgets to plan their future expenses according to their economy.

On the other hand, in the research by Pinto and Martines (2017) conducted with 200 Colombian students in the fifth and sixth semesters, significant correlations were found with the age of the respondents, i.e., within the database obtained in the surveys, it was observed that the level of financial education of students is more closely associated with the age itself, of an individual, than with their professional training.

For Mungaray et al. (2021), the strategy to increase the levels of financial education in Mexico is in line with the changes in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and economic behavior. In other words, increasing these levels can help improve social inclusion and well-being because it allows access to various financial services based on the level of income of each individual. A State that provides mechanisms and resources will generate benefits and opportunities for the low-income population that will increase their level of financial education in the long term.

Likewise, Grisal et al. (2016) conducted a research study with university students in the first semester of the Economics and Finance programs at the Institución Universitaria Esumer, where low financial skills were evidenced. On the one hand, it is known that 40% of the population recognizes that a good financial education is useful for all fields of life. On the other hand, only 52% consider money as their security, 21% see it as their independence, while, for 12% of the population, it represents success. Finally, for the rest of the population, it only represents anguish and fear.

On the other hand, Avendaño et al. (2021) conducted a study with 1514 Colombian students showing that participants have an interest in knowing, learning, and exploring the topics used in finance. Likewise, it was also evidenced that they do not know about the topics of default, management fees, and revolving credits, among others. Finally, it is concluded that an adequate financial education is an instrument for the development of financial-economic skills since, without financial education, people are more likely to live precariously.

Considering the above mentioned, it can be deduced that it is important to receive financial education at an early age since it will influence the individual’s economic formation throughout life. This study aims to determine the level of financial education of the students of a private university in Lima, the capital of Peru, who have already received formal instruction in finance-related topics (Gibson et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2021). Based on the evidence, the following research hypotheses are proposed: Hi 1: university students know how to calculate interest rates; Hi 2: university students understand the importance of inflation and its management within the economy; Hi 3: university students understand the importance of savings and economic security; Hi 4: university students make adequate use of their credit cards; Hi 5: university students prepare budgets to plan their income and expenses.

The research is justified because it is a contribution to young people, citizens or institutions that practice or promote the importance of learning about finance or financial topics, because, thanks to this research, it has been possible to observe closely how economic problems or afflictions can destroy lives unless awareness is raised and prevention is sought through the proper education on topics such as savings, interest rates, budgets, inflation, among others.

Methodology

A quantitative approach with a non-experimental design was applied because there is no manipulation of the independent variables; it is cross-sectional since the data collection was carried out at a single moment. The sample is made up of 365 current students of a university in Northern Lima, from different degree programs belonging to the School of Business, from the sixth to the tenth semester, and who have received formal instruction in subjects related to finance through courses such as Business Administration, General Accounting, Microeconomics, Macroeconomics, Costs and Budgets, Financial Administration, Probability and Statistics.

The information was obtained through the questionnaire used by Moreno et al. (2017) in their research on the level of financial education in young university students in Mexico. The methodology was used by three financial institutions (CONDUSEF, BANAMEX-UNAM, and FINRA) to evaluate knowledge about the interest rate, inflation, savings, credit card use, and budgeting. The data collection tool consists of 39 questions, divided into 5 sections according to the dimensions of the variables: savings, inflation, credit card, budgeting, and interest; with dichotomous and multiple-choice variables. The population is made up of 4800 students; the sampling is probabilistic and the following parameters were considered: confidence level of 95%, error margin of 5%, probability of occurrence of 50%, and probability of non-occurrence of 50%.

For data collection, Google Forms was applied, where an introduction to the topic was presented, the consent of the respondent was requested, and, finally, the questionnaire. The fieldwork was conducted between March and May 2022 and, due to a pandemic situation, the distribution of the survey was carried out through digital channels such as Facebook and WhatsApp. To interpret the data, measures of central tendency (mean, median, and mode) were used for the questions in the questionnaire.

From an ethical point of view, the research is anonymous and does not reveal the name of the respondents. The sample indicated in the methodology section was completely applied; the respondents answered voluntarily, without any pressure; all the ideas presented in the research were cited, giving credit to the authors who supported its development; the data presented correspond to the date indicated.

Results

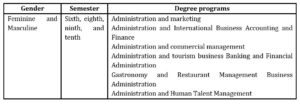

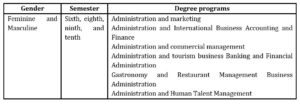

Table 1 presents the demographic data such as gender, semester, degree programs, and district of residence of the surveyed university students.

Table 1: Demographic data of participants

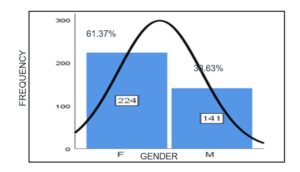

Female participation of 61.37% and male participation of 38.63% were obtained, from the sixth, tenth, eighth and ninth semesters, with percentages of 13.8%, 14.1%, 3.3%, and 7.6%, respectively; from the degree programs of Administration and Marketing with 26.8%, Administration and International Business with 14. 2%, Accounting and Finance with 3.0%, Administration and Commercial Management with 1.4%, Administration and Tourism Business with 27.7%, Banking and Financial Administration with 3.0%, Economics with 6.8%, Gastronomy and Restaurant Management with 0.8%, Business Administration with 15.3%, Administration and Human Talent Management with 0.8%.

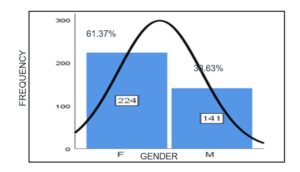

Figure 2 shows that the sample consisted of 61.37% women and 38.63% men.

Figure 2: Sample Gender

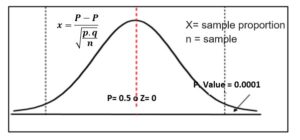

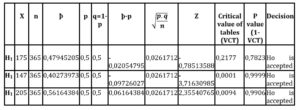

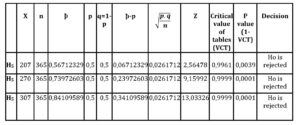

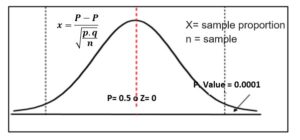

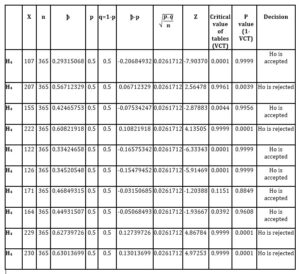

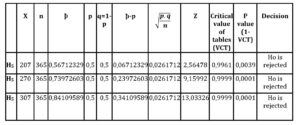

To contrast the working hypotheses, the test for proportion assertion was applied (Ho: p=0.5, Hi: p> 0.5), see Figure 3.

Figure 3: Statistical Form

Results in tables and discussion of data

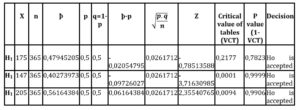

On the interest rate dimension

Table 2: Hi (1) School of Business students know how to calculate interest rates

Regarding hypothesis 1, Table 2 shows that students do not perform calculations with interest rates, so the Ho is accepted.

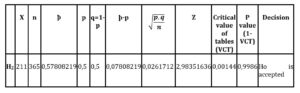

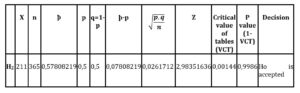

On the inflation dimension

Table 3: Hi (2) Business School students understand the importance of inflation and take it into account when evaluating money

Regarding hypothesis 2, the results obtained in Table 3 show that students do not consider inflation, nor do they take it into account when evaluating their money. Ho is accepted.

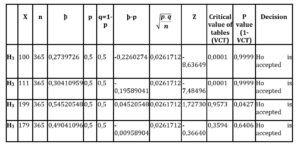

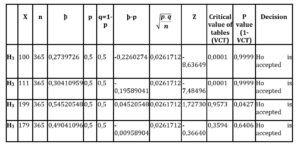

On the savings dimension

Table 4: Hi (3) Business school students understand the importance of savings and financial security

Regarding hypothesis 3, the results obtained in Table 4 show that students do not give the appropriate importance to savings and economic security.

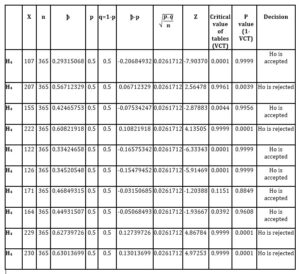

About the credit card dimension

Table 5: Hi (4) Business school students make appropriate use of their credit cards

Regarding hypothesis 4, the results obtained in Table 5 show that the surveyed population does not have an acceptable level of financial education in terms of credit card management, except for items 32 (credit cards they do not use) and 35 (characteristics when choosing a credit card).

On the budgeting dimension

Table 6: Hi (5) Business School students plan their expenses by preparing a budget

Regarding hypothesis 5, the results obtained in Table 6 show that university students have a sufficient level of financial education related to budgeting.

Discussion

The analysis of results shows that most university students do not calculate interest rates correctly. On the other hand, when interpreting and calculating the price of bonds or debt, they demonstrate a low level. These results are similar to what Moreno et al. (2017) refer to, stating that insecurity or the lack of knowledge about finance leads to not investing adequately.

Regarding the inflation dimension, it is shown that university students do not consider it in the calculation of the valuation of their money, so they do not take interest in protecting their savings. These results agree with Avendaño et al. (2021), who state that there are basic financial skills that support the development of others, for example, the habit of saving or the use of tools such as the calculation of the valuation of an asset, since knowing and applying inflation within this valuation would be a basic skill for a healthy financial life.

The result obtained in the savings dimension shows that students are not used to saving to obtain economic security. This result coincides with Escobar et al. (2016); who mentions that being cultured in financial matters will contribute to the improvement of the quality of life of people who do not have sufficient economic resources to finance microenterprise activities.

The evidence obtained regarding the use of credit cards shows that the population of surveyed students does not have sufficient skills for credit card management yet. The result is similar to the evidence found by Tinoco (2018), who highlights that having little knowledge of risk and caution before financial entities often leads to requesting a type of credit based on a financial need, and, in this particular case, it is highlighted that the vast majority of university students have access to credit through a credit card.

Finally, the results obtained in the budgeting dimension are favorable as they show that young people are concerned about the elaboration of income and expenses based on their economic possibilities. According to Orozco et al. (2016), a financially educated person will be less likely to fail. The mastery of general financial concepts should be a basic skill of every professional.

It is not a coincidence that the results found by other studies around the world, especially in Latin America, are so similar to those presented in this research, as this only demonstrates the need for a greater insertion of financial education in the Peruvian curriculum. Including programs or courses in the education of young people and children at an earlier age would contribute to improving money management in their personal and professional lives.

Regarding demographic aspects, this research is in line with others. Mejía et al. (2015) conclude that people from an urban sector have greater knowledge, behavior, and attitudes related to finances, compared to the rural sector. Regarding gender, men show greater financial knowledge and behavior. García et al. (2021) argue that men have greater financial knowledge and women have a greater financial attitude. They also indicate that older adults like to save and have financial planning, and young people prefer to have knowledge that will help them acquire better financial behavior.

It should be mentioned that this study was subject to limitations: only students of a private university in Lima were sampled, so it is not possible to generalize about the entire Peruvian university student population. On the other hand, the Covid 19 pandemic made it necessary to apply the questionnaire virtually, which delayed the fieldwork.

It is proposed to conduct similar research in other Peruvian universities, comparing the level of financial education in students of private and public universities. It is also proposed to conduct experimental research teaching aspects of financial education to students in basic education, in order to measure their level and financial behavior at university.

Conclusions

The level of financial education of the students of a private university in Lima, the capital of Peru, who have already received formal instruction in finance-related topics, is low. Most students do not know how to measure interest rates correctly, do not understand the importance of inflation and its management within the economy, do not understand the importance of savings and financial security, do not make proper use of their credit cards, but do budget to plan their income and expenses.

According to the analysis of other research, these results are similar to those of university students in other Latin American countries. It is recommended that universities teach finance courses in a more practical way that applies to students’ daily life, seeking to develop knowledge and attitudes toward finances. Finally, it is emphasized that financial education should be present in the basic education curriculum, which would allow students to practice it from an early age at home so that they are better prepared when they are young.

References

- Arango, L., Chavarro, X. and González, E. (2015), ‘Choques de precios de materias primas, inflación y política monetaria óptima: el caso de Colombia,’ Monetaria, 0 (2), 227-277.

- Assusa, G., Freyre, M. L. and Merino, F. (2019), ‘Estrategias económicas y desigualdad social. Dinámicas de consumo, ahorro y finanzas de familias cordobesas,’ Población & sociedad, 26(2), 1-33. doi: 10.19137/pys-2019-260201

- Avilez Silva, L. E., Flores Vidal, R. A. and Gamarra Almonacid, L. A. (2017), Impacto de la aplicación de la estrategia nacional de inclusión financiera (ENIF) en el diseño de la estructura organizacional del Banco de la Nación. [Online], [Retrieved on September 10, 2021], http://intra.uigv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.11818/1301

- Avendaño, W. R., Rueda, G. and Velasco, B. M. (2021), ‘Percepciones y habilidades financieras en estudiantes universitarios,’ Formación universitaria, 14(3), 95-104. doi: 10.4067/S0718-50062021000300095

- Castro Romero, P. J. H. (2014), Influencia de la cultura financiera en los clientes del Banco de Crédito del Perú de la ciudad de Chiclayo, en el uso de tarjetas de crédito, en el periodo enero–julio del 2013. [Online], [Retrieved on December 20, 2021], https://tesis.usat.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12423/636

- Chiquiar, D. and Ibarra, R. (2020), ‘La independencia de los bancos centrales y la inflación: un análisis empírico’, Investigación económica, 79(311), 4-34. doi: 10.22201/fe.01851667p.2020.311.72433

- Copaja, E. E. W. and Alvarón, R. R. B. (2019), ‘Educación financiera papel importante en la formación de profesionales en la región de Tacna,’ Iberoamerican Business Journal: Revista de Estudios Internacionales, 2(2), 4-19. doi: 10.22451/5817.ibj2019.vol2.2.11019

- Cruz Barba, E. (2018), ‘Educación financiera en los niños: una evidencia empírica,’ Sinéctica, (51). doi: 10.31391/s2007-7033(2018)0051-012

- Escobar-Váquiro, N., Benavides-Franco, J., & Perafán-Peña, H. F. (2016), ‘Governança corporativa e desempenho financeiro: conceitos teóricos e evidencia empírica,’ Cuadernos de contabilidad, 17(43), 203-254. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.cc17-43.gcdf.

- García Mata, O., Zorrilla del Castillo, A. L., Briseño García, A. and Arango Herrera, E. (2021), ‘Actitud financiera, comportamiento y conocimiento financieros en México,’ Cuadernos de Economía, 40(83), 431-457. doi: 10.15446/cuad.econ.v40n83.83247

- Gibson, P., Sam, J. K. and Cheng, Y. (2022), ‘The value of financial education during multiple life stages. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning,’ 33(1), 24-43. doi: 10.1891/JFCP-20-00017

- Goyal, K. and Kumar, S. (2021), ‘Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis,’ International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(1), 80-105. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12605

- Grisal, E. A. D., Ruiz, J. D. G. and Aristizábal, J. D. R. (2016), ‘Conocimientos financieros en jóvenes universitarios: caracterización en la institución universitaria ESUMER,’ Revista de pedagogía, 37(101), 41-55.

- Guerrero, R., Villamizar, J. M. and Maestre, M. (2018), ‘Las finanzas personales desde la educación básica en instituciones de Pamplona,’ Desarrollo Gerencial, 10(2), 9-24. doi: 10.17081/dege.10.2.3180

- Gutiérrez Andrade, O. W. and Delgadillo Sánchez, J. A. (2018), ‘La educación financiera en jóvenes universitarios del primer ciclo de pregrado de la Universidad Católica Boliviana San Pablo, Unidad Académica Regional de Cochabamba,’ Revista Perspectivas, (41), 33-72.

- Kaiser, T. and Menkhoff, L. (2020), ‘Financial education in schools: A meta-analysis of experimental studies,’ Economics of Education Review, 78 doi: 1016/j.econedurev.2019.101930

- Kim, K. T., Lee, J. M. and Lee, J. (2021), ‘Student loans and financial satisfaction: The moderating role of financial education,’ Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 32(2), 266-279. doi: 10.1891/JFCP-19-00002

- López-Guzmán, T., Pérez Gálvez, J. C., Cordova Buiza, F. and Medina-Viruel, M. J. (2019), ‘Emotional perception and historical heritage: A segmentation of foreign tourists who visit the city of Lima,’ International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(3), 451-464. doi: 1108/IJTC-06-2018-0046

- López, J. A. P. (2021), ‘Educación financiera en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje de los estudiantes de Bachillerato del Liceo Francés de San Salvador,’ Conocimiento Educativo, 8, 147-157. doi: 10.5377/ce.v8i1.12596

- Lusardi, A. (2019), ‘Financial literacy and the need for financial education: Evidence and implications,’ Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 155(1). doi: 10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

- Mejía, D., Pallotta, A. and Egúsquiza, E. (2015), Encuesta de medición de las capacidades financieras en los países andinos. Informe comparativo 2014. [Online], [Retrieved on July 25, 2022], http://scioteca.caf.com/handle/123456789/740

- Moreno, E., García, A., y Gutiérrez, L. (2017), ‘Nivel de educación financiera en escenarios de educación superior. Un estudio empírico con estudiantes del área económico-administrativa,’ Revista iberoamericana de educación superior, 8(22), 163-183.

- Mungaray, A., González, N. and Osorio, G. (2021), ‘Financial education and its effect on income in Mexico,’ Problemas del desarrollo, 52(205), 55-78. doi: 10.22201/iiec.20078951e.2021.205.69709

- Orozco, N. C., Franco, M. A. and González, I. C. (2016), ‘Educación financiera en los estudiantes de pregrado de la Universidad del Quindío,’ Sinapsis, 8(2), 99-120.

- Pérez, P. P., Vásconez, O. J., & González, R. R. (2021), ‘Concentración y tasas de Interés en el sistema financiero ecuatoriano,’ Revista Economía, 73(117), 93-104. doi: 10.29166/economia.v73i117.2629

- Pinto, L. B. and Martínez, E. G. (2017), ‘Educación financiera en estudiantes universitarios,’ ECONÓMICAS CUC, 38(2), 101-112. doi: 10.17981/econcuc.38.2.2017.08

- Raccanello, K., & Guzmán, E. H. (2014), ‘Educación e inclusión financiera,’ Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos (México), 44(2), 119-141.

- Ribeiro, J. (2019), ‘Inflación de alimentos en Perú: El rol de la política monetaria. Revista de análisis económico,’ 34(2), 81-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-88702019000200081

- Salazar-Rebaza, C., Aguilar-Sotelo, F., Zegarra-Alva, M. and Cordova-Buiza, F. (2022), ‘Financing in the alternative securities market: Economic and financial impact on SMEs,’ Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 19(2), 1-13. doi: 10.21511/imfi.19(2).2022.01

- Saxunova, D., Le Roux, C. L. and Oster, M. (2022), ‘Financial and economic impact of brexit and COVID-19 in the United Kingdom,’ IBIMA Business Review, 2022. doi: 10.5171/2022.834462

- Tinoco Hinostroza, W. S. (2018), Educación financiera en estudiantes universitarios de una universidad del departamento de Junín-2017. [Online], [Retrieved on May 15, 2022], https://www.lareferencia.info/vufind/Record/PE_1af761a0517106fa1884f271f977c90b

- Vanegas, J. G., Arango Mesa, M. A., Gómez-Betancur, L. and Cortés-Cardona, D. (2020), ‘Educación financiera en mujeres: un estudio en el barrio López de Mesa de Medellín,’ Revista Facultad de Ciencias Económicas: Investigación y Reflexión, 28(2), 121-141. doi: 10.18359/rfce.4929

- Vargas Prieto, M. and Avendaño Prieto, B. L. (2014), ‘Diseño y análisis psicométrico de un instrumento que evalúa competencias básicas en Economía y Finanzas: una contribución a la educación para el consumo,’ Universitas Psychologica, 13(4), 1379-1393. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-4.dapi

- Villada, F., López-Lezama, J. M. and Muñoz-Galeano, N. (2017), ‘El Papel de la Educación Financiera en la Formación de Profesionales de la Ingeniería,’ Formación universitaria, 10(2), 13-22. doi: 10.4067/S0718-50062017000200003

- Villada, F., López-Lezama, J. M. and Muñoz-Galeano, N. (2018), ‘Análisis de la Relación entre Rentabilidad y Riesgo en la Planeación de las Finanzas Personales,’ Formación universitaria, 11(6), 41-52. doi: 10.4067/S0718-50062018000600041

- Zarate Castañeda, K., Chong Chong, J. C., Ventura, E. and Mejía, D. (2021). Encuesta de medición de capacidades financieras de Perú 2019. Caracas: Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y AFP (SBS) de Perú y CAF. [Online], [Retrieved on July 12, 2022], http://scioteca.caf.com/handle/123456789/1689

Appendix

- I agree to answer the following questions:

- Campus

- Comas

- Los Olivos

- Breña

- San Juan de Lurigancho

- Chorrillos

- Others

- Degree Programs

- Administration and marketing

- Administration and International Business

- Accounting and Finance

- Administration and commercial management

- Administration and tourism business

- Banking and Financial Administration

- Economics

- Gastronomy and Restaurant Management

- Public Administration and Management

- Business Administration

- Administration and Human Talent Management

- Other

- Semester

- Sixth

- Seventh

- Eighth

- Ninth

- Tenth

- Other

- Gender

- Age

- Under 18 years old

- Between 18 and 21

- Between 22 and 25

- Between 26 and 29

- Between 30 and over

INTEREST RATE

- Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account is 1% per year and inflation is 2% per year. After 1 year, how much could you buy with the money in this account?

- More than today

- The same as today

- Less than today

- I do not know

- I prefer not to answer

- If the interest rate rises, what will happen – normally – to the price of bonds?

- It will go up

- It will go down

- It will stay the same

- There is no relationship between bond prices and interest rates.

- I don’t know

- I prefer not to answer

- A 15-year mortgage typically requires higher monthly payments than a 30-year mortgage, but the total interest paid over the life of the loan will be lower.

- True

- False

- I don’t know

- I prefer not to answer

INFLATION

- Are your savings protected against current inflation?

- Yes, I put my money in financial products that provide me with returns above inflation.

- Yes, the bank where I save my money tells me that I have high yields.

- I do not know

SAVINGS

- What are savings?

- Saving money

- Having money for emergencies

- Something for the future

- Not spending

- Having money available

- Money in the bank

- Financial security

- Money accumulated to buy

- What is the main reason you save or would save?

- To save

- Personal expenses

- For old age

- When there is no work

- Education

- From the previous question, please number the order of importance you would give to the reasons for saving. Where 1 (one) is the most important and 5 (five) is the least important.

- To save

- Personal expenses

- For old age

- When there is no work

- Education

- How do you determine what you save?

- I save what I have left over.

- I save when I want to buy or do something.

- I am in the habit of saving.

- I do not have enough.

- When you have money left over (from your spending, from your salary, from the money you receive), what do you use it on most often?

- I don’t save it.

- I don’t have money left over.

- I save it.

- I use it to pay debts.

- I spend it on clothes.

- I spend it on entertainment.

- What is the main reason you save or would save?

- Housing (purchase, remodeling, or maintenance)

- From the previous question, number in order of importance the reasons why you would save, where 1 (one) is the most important and 9 (nine) is the least important

- Housing (purchase, remodeling, maintenance

- When there is no work available.

- For old age.

- Personal expenses.

- To save it.

- What is the main reason you have never had or would not have a savings, deposit, or investment account?

- I cannot afford it.

- It does not interest me.

- I am suspicious.

- There are too many requirements.

- The interest rate is too low.

- Very high commissions are charged.

- A very high initial deposit is required.

- Minimum balance required.

- I do not know.

- From the previous question, number in order of importance the reasons why you do not have or would not have a savings or investment account, where 1 (one) is the most important and 9 (nine) is the least important.

- I cannot afford it.

- It does not interest me.

- I am suspicious.

- There are too many requirements.

- The interest rate is too low.

- Very high commissions are charged.

- A very high initial deposit is required.

- Minimum balance required.

- I do not know

- From the following answer options, indicate the one that is closest to your definition of what an investment is for you.

- To buy something for making a profit.

- Money in a business.

- To make a profit.

- Profit in the future.

- To put money to work.

- To buy goods.

- To save.

- To generate returns.

- If you have surpluses that allow you to save: Where do you keep your savings for emergencies?

- Short-term liquid instruments (1 to 28-day deposits, short-term debt mutual fund).

- Long-term instruments (365-day deposits, stocks, long-term debt mutual fund).

- I do not save for contingencies or emergencies.

CREDIT CARD

- What is a credit for you?

- It is a loan.

- It is a loan that is paid in installments.

- It is a debt.

- An interest-bearing loan.

- Help to solve a problem.

- It is a problem.

- How often do you usually read or learn about savings accounts, credit cards, and credit?

- Never

- Occasionally, when I need it.

- Always

- What is the main risk of taking out a loan?

- Getting into debt.

- Not paying and losing equity.

- Paying high interest or increased interest.

- Do you use credit cards at home?

- If yes, how many credit cards do you have?

- 1 – 2

- 3 – 4

- More than 4.

- Not applicable – I do not have a credit card.

- If you have a credit card, when you pay: what do you do most frequently?

- I pay the full amount.

- I pay a little more than the minimum.

- I pay the minimum payment.

- Not applicable – I do not have a credit card.

- Regardless of whether or not you have a credit card, for you, what is the main advantage of using a credit card?

- Possibility to buy when there is no money.

- Handling less cash.

- Unforeseen events.

- To avoid muggings.

- Buying in markets and department stores.

-

- In general terms, how do you prefer to manage your money?

- Cash

- Credit Card

- Debit Card

- Check

- Other:

- You or any member of the household frequently performs operations in:

- Branch office.

- Automatic teller machines.

- Before choosing a loan, do you compare the annual effective cost rate (TCEA)?

- Not always because I doubt that it is useful.

- I do not know what TCEA is.

- Do you have unused credit cards?

- No, I cancel those I don’t use.

- Yes, every card can be useful someday.

- I use all of them, and with some cards I finance the debts of other cards.

- Do you know your credit card payment deadline?

- Yes, I register it in my calendar and my cell phone alarm so I don’t forget it.

- Sometimes I forget it and have to pay a late payment fee.

- No, I pay when I have the money to do so.

- In your opinion, what do you think the credit card is most useful for?

- To finance my expenses at 50 days interest-free (paying my debt in full before the payment deadline).

- To cover unexpected expenses.

- To complete my family’s expenses.

- Finally, when acquiring a new credit card, you make a choice because:

- It suits my needs as it has an adequate annual effective cost rate (TCEA).

- They are offered to me.

- It gives me status (university, soccer team, Gold or Premier cards).

BUDGET

- Do you usually keep track of your debts, expenses, income, and savings?

- Yes

- No

- Yes, of debts.

- Yes, of expenses

- Yes, of income

- Yes, savings

- Other:

- Do you know how to make a budget to plan the distribution of your money?

- Were the expenses you incurred during the past month within your financial means?

- Yes

- No, but I asked for a credit.

- No

- If you had the opportunity to “ideally” distribute your budget according to your monthly household income, what would be the order of your priorities? List in order of importance according to your priorities, where 1 is the most important and 11 is the least important.

- Clothing and footwear.

- Payment of debts.

- Gasoline and/or public transportation.

- Car credit.

- Saving for retirement0

- Housing service