Introduction

Public sector internal audit was established in Malaysia through Treasury Circular Ref. 2 of 1979 [32], applicable to Federal Government Agencies. In 2004, the scope of public sector internal audit was extended to all Ministries, state governments and agencies of state governments. Internal auditing is crucial in ensuring the government’s efficiency, economy and effectiveness of all levels of public sector administration (IIA Research Foundation, 2009). Internal audit of public sector organisations ensures productive public funds management, consequently avoiding misused or mismanaged government budgets. In providing the efficiency and effectiveness of government projects, independent monitoring by the public sector internal auditors is required (Ahmad, Othman, Othman and Jusoff, 2009). Internal auditors assure the organisation’s governance through a systematic approach in monitoring internal control, compliance review and risk management processes (Ayagre, 2015).

As a provider of value-added consulting activity, there is an increase in attention on the practicality of the internal auditor in providing good governance (Allegrini, D’Onza, Paape, Melville and Sarens, 2006). The internal auditors’ role has become an essential element of an organisation’s governance (Bilal, Twafik and Bakhit, 2018). The significant revolution in managing the complexity of administration, risk, controls and compliance offers a huge opportunity to add a greater value to internal auditors’ role (Diana and Nicolae, 2012). Internal auditors have a broader job scope in detecting organisational wrongdoings than external auditors. Internal auditors may encounter suspicious and severe matters while performing their audit work. Therefore, internal auditors are responsible for reporting the issue since the reporting duty is embedded in their role. As a result, when internal auditors face this situation, they need to blow their whistle.

The prestige of the internal audit profession promotes ethical culture and integrity. This profession demands the responsibilities of internal auditors as stated in the Code of Ethics of the Institute of Internal Auditors. The Code requires internal auditors to have an uncompromising adherence to moral values while performing a public service. The law and the Code guided the internal auditors’ disclosures. Failure to disclose the required material facts may limit the report’s credibility and impair the profession’s image accordingly. Moreover, internal auditors are expected to have a solid working knowledge of the upcoming changes in the overall operations of an organisation (Kahyaoglu and Caliyurt, 2018). Internal auditors have more opportunities to blow their whistle with the unique position since they have easy access to their records and documents. This access creates a more precise involvement of the internal auditors with the internal affairs of their organisations. Therefore, internal auditors are reliable in reporting organisations’ wrongdoing.

In recognising the significant contribution of whistleblowing practices to the internal auditing profession, ongoing studies delved into this area of study. Even though the whistleblowing idea is accepted, it is considered a very complex decision process (Sharif, 2015). The complexity of whistleblowing may allow researchers to explore the influencing factors of whistleblowing intention among public sector internal auditors. Among recent studies conducted in measuring the whistleblowing practice among public sector internal auditors were Anggraini and Siswanto (2016) on the role of perceived behavioural control and subjective norms towards wrongdoing reporting, Humantito (2017) on whistleblowing decisions in responding to corporate corruption in government internal audit units, Darjoko and Nahartyo (2017) on factors influencing the investigation of whistleblowing reporting and Cheisviyanny and Arza (2019) on the states of whistleblowing intention in Indonesia.

In 2017, Malaysia scored an all-time high ranking of 62, the worst Corruption Perception Index (CPI) ever. The analyst commented on the issues that led to the worst CPI of 2017, including the 1MDB scandal, the Sabah Water Department scandal, the FELDA scandal, and the National Feedlot Corporation scandal. The series of scandals reflect the loss of faith among the public, investor and market players. These scandals can be detected and prevented if the corruption incidences are disclosed to the enforcement agencies. Even though reporting wrongdoing or whistleblowing is a tough decision, continuous effort to examine the factors influencing the whistleblowing intention provides valuable insights into combating corruption. Therefore, this study will examine the factors influencing whistleblowing intention among Malaysian public sector internal auditors. Delved into this study may add to the whistleblowing literature in Malaysia. There are limited studies on measuring whistleblowing intentions in Malaysia (Ahmad, 2011). This study is essential since Malaysia is still struggling to fight against corruption.

Literature Review

Whistleblowing is defined as reporting or disclosing wrongdoings or misbehaviour in an organisation. It is a voluntary disclosure process about an organisation members’ misconduct to the appropriate authorities inside the organisation (MacNab and Worthley, 2008). Whistleblowing constitutes a disclosure or reporting of illegal or unethical behaviours by the organisation members to their employers to take remedial actions (Near and Miceli, 1985). This study will examine four factors influencing whistleblowing intention: self-efficacy, empathy, ethical leadership, and power distance.

Self-efficacy and Whistleblowing Intention

Accountant General’s Department of Malaysia (AGD) developed Strategic Plan 2019-2023 that aims to be fully committed to protect the public priority and to enhance the accountability and transparency of public sectors financial and accounting management. Internal audit plays a significant role in supporting the credibility of AGD in compliance and regulatory practice. Internal audit will ensure the collection and payment will be correctly accounted for and provide the internal control of financial and accounting management in public sector organisations and state governments. Despite having high skills in accounting practice, the Eleventh Malaysia Plan 2016-2020 highlighted that accountants of AGD have low confidence in expressing their opinions. Having low courage to share their thoughts may impact their professionalism. Without confidence, individuals will not be sure about the benefits of whistleblowing to the organisation (Kuncara, Furqorina and Payamta, 2017). MacNab and Worthley (2008) also commented that employees with high self-efficacy would tend to be more confident reporting misbehaviour in their organisation because they have determined their actions.

Self-efficacy is a person’s belief that something is good or bad, correct or wrong and capable or incapable of performing a particular task (Yuliani, Kusumah and Sumarmo, 2019). In this study, self-efficacy was justified as a judgment of individuals’ capabilities that motivate them to whistleblow. Various studies supported the linear relationship between self-efficacy and successive performance of a task (Ede, Sullivan and Feltz, 2017), including whistleblowing. Sharif (2015) investigated whether self-efficacy influences the internal auditors’ whistleblowing intention. This study found that self-efficacy is a strong predictor of whistleblowing intention that resulted from effective whistleblowing mechanisms employed in most organisations in the UK. In addition, the rules legislated by the UK regulators and the government further strengthen the establishment of effective whistleblowing policies and procedures for protecting whistleblowers. Orhan and Oyzer (2016) examined the relationship between self-efficacy and graduates’ whistleblowing intention in Turkey. The results of this study proved that high-self efficacy influenced the likelihood of graduates’ whistleblowing. This study found an interesting finding contrary to the Turkish culture that individuals with high self-efficacy will be less likely to whistleblow. Therefore, to examine the relationship between self-efficacy and whistleblowing intention, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H1: There is a significant positive relationship between self-efficacy and whistleblowing intention.

Empathy and Whistleblowing Intention

In an internal audit, ethical decision making is crucial to the internal auditors in balancing the competing interest between the organisations and the duty to safeguard the public’s interest. As suggested by OECD Recommendations on Public Integrity 2017, ethical decision-making may prevent unethical behaviour in the public sector. Hence, ethical decision making is crucial to the public sector internal auditors. Victor and Cullen (1998) recommended that caring climates influence ethical decision making. A caring climate explains the primary consideration of what is best for every organisation member (Victor and Cullen, 1998). This climate decreases the likelihood of unethical behaviour and increases professional commitment and satisfaction (Shafer, 2008; Shafer, Simmons and Yip, 2016). Martin and Cullen (2006) found that a caring climate or benevolence is the most common ethical climate associated with high empathy (Myyry and Helkama, 2001). Empathy can be defined as the ability to understand others’ needs. Empathy plays a significant role in influencing individuals’ ethical decision making, particularly in understanding the interest to carry out prosocial behaviour (Brown, Sautter, Littvay, Sautter and Bearnes, 2010). Individuals with high empathetic values are associated with altruistic behaviour that leads to genuine feelings of emotional concern for others (Rogers, Clow and Kash, 1994).

Ismail and Yuhanis (2018) revealed that Malaysian public sector internal auditors were only associated with law and code climate, not caring climate. This finding may challenge the empathic value that justifies the ability of public sector internal auditors to understand the needs of organisations and the public in their ethical decision. Internal auditors’ empathy helps experience sharing, improves a sense of belonging and guides their ethical decision making (Brown et al., 2010). Hence, improving empathy is crucial among public sector internal auditors since ethical decision making would increase their whistleblowing intention (Valentine and Godkin, 2019). By understanding the needs of others, internal auditors will whistleblow with the intent of benefitting the organisation and the public. Immediate actions are required to improve their empathy since Arifin and Ahmad (2017) proved a culture of fear to whistleblow and poor empathic value had diminished integrity in the Malaysian public sector. Hence, the following hypothesis was formulated to determine the relationship between empathy and whistleblowing intention:

H2: There is a significant positive relationship between empathy and whistleblowing intention.

Ethical leadership and Whistleblowing Intention

The corruption cases involving public sector employees affected public sector organisations’ accountability in Malaysia. According to Transparency International Malaysia, corruption has cost the country about RM46.9 billion in 2017 (The Star, 2018). During the recent seminar held by MACC, Chief Commissioner Datuk Seri Azam Bakri highlighted the severe and worrying trend of power abuse and corruption culture in Malaysia (MACC, 2021). a study on ethical leadership and integrity violation in local governments by Hamoudah, Othman, Abdul Rahman, Mohd Noor and Alamoudi (2021) implied acceptable unethical behaviours among Malaysian leaders. These negative trends indicate that corrupt leadership negatively impacts the leadership role in combating bribery in Malaysian public sector organisations. Zahari, Said and Muhamad’s (2021) study highlighted the ethical leadership role in preventing corruption in these organisations.

An ethical leader should be a moral person typified as high integrity, trustworthiness, unbiased and sticks to ethical standards in decision-making (Lee, Choi, Youn and Chun, 2017). Ethical leaders may inspire employees to do the right things and cultivate ethical behaviour among them. As a role model in the organisation, ethical leaders ensure a fair working environment with clear ethical standards will inspire employees to acknowledge ethical issues in their decisions (Lee, Choi, Youn and Chun, 2017). Ethical leaders also support two-way communication that incorporates honesty, openness and trustworthiness, decision making, and reinforcement, reducing the uncertainty of reporting consequences among the employees (Malik and Nawaz, 2018). Therefore, employees feel safe blowing the whistle as they are not afraid of being caught, retaliated or penalised (Rabie and Malek, 2020). In China, ethical leaders were proven to influence whistleblowing practice (Liu, Liao and Wei, 2015). Zakaria, Razak and Yusoff (2016) also found that leadership is the most influential factor in supporting whistleblowing practice in Malaysian public sector organisations. In this study, to investigate the relationship between ethical leadership and whistleblowing intention, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H3: There is a significant positive relationship between ethical leadership and whistleblowing intention.

Power Distance and Whistleblowing Intention

Hofstede Insights 2021 reveal a very high score on the Malaysian Power Distance Index, suggesting that Malaysians accept hierarchical relationships and highly respect authority. Power distance made everyone fit accordingly at their place, in which no further justification is needed to explain this atmosphere. High power distance is not new to Malaysia since Hofstede’s (2001) study already showed Malaysia has the highest level of power distance among the societies examined. High power distance made workers must comply with their leaders’ instructions. Due to seniority, leaders regard it as a natural order that needs to comply and employees should agree with the management decision. (Hsiung and Tsai, 2017). This study further commented that the culture of accepting inequalities, centralisation decisions, and employees expecting to be told what to do might affect whistleblowing practice. It is unlikely that employees will blow their whistle against their top management’s wrongdoings.

Power distance manifested in an organisation with top management openly established their rank and power. The more significant power inequalities in an organisation, the less likely the employees will demonstrate their resistance. Legitimacy power in an organisation also acknowledged that seniority should be honoured and feared (Puni and Hilton, 2020). As a result, this may limit whistleblowing practice, which is not encouraged within the organisations. This is supported by Rachagan and Kuppusamy’s (2013) study that suggested WPA 2010 implementation is not necessarily the only solution to improve the whistleblowing practice in Malaysia due to the high-power distance. Meanwhile, Abdul, Yusoff and Mohamed (2019) revealed high power discretion in the Royal Malaysian Customs Department could reduce the likelihood of employees reporting wrongdoings. In other jurisdictions, Park, Rehg and Lee (2005) and Bashir, Khattak, Hanif and Chohan (2011) also found that hierarchical order and organisational reprisal may deter wrongdoing reporting in Pakistan and South Korea public sector. The following hypothesis was formulated to inspect the relationship between power distance and whistleblowing intention:

H4: There is a significant negative relationship between power distance and whistleblowing intention.

Methodology

This study investigates the factors influencing whistleblowing intention among public sector internal auditors. This study decided to deploy a quantitative approach through questionnaire distribution. The population designated for this study consists of public sector internal auditors of 25 ministries in Malaysia. In this study, 210 public sector internal auditors were selected as the respondents. In measuring the predictors’ constructs, the survey from Park et al. (2008) with five items will be adapted to measure whistleblowing intention. For self-efficacy and empathy, items survey by Tavousi et al. (2009) and Davis (1980) will be adopted, respectively. For ethical leadership, items survey from Brown et al. (2005) will be employed. Meanwhile, items survey from Dorfman and Howell (1988) will be adopted for power distance. This study deploys Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) as an instrument to analyse the collected data. SmartPLS 3 software was used to analyse the data collected from the questionnaire.

Results and Discussion

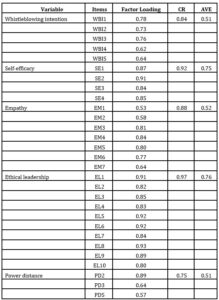

In Partial Least Square (PLS) path model, the goodness of the measurement model is measured via discriminant and convergent validity. The reliability and validity of any measurement procedure significantly influence the competence and effectiveness of a study. Convergent validity will be evaluated by factor loading, Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson, 2010). Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt (2013) proposed that the factor loading of items should exceed the value of 0.5 to certify that main loading, indicator reliability and items cross-loading were verified. Therefore, Hair et al. (2013) suggested that items with low factor loading (less than 0.5) will be deleted. In this study, three items with low factor loading were deleted involving PD1, PD4 and PD6.

Composite reliability indicates the internal consistency of measurement items (Hyland, Boduszek, Dhingra, Shevlin and Egan, 2014). Hair et al. (2010) suggested a threshold value of 0.7 that indicates a high reliability of measurement items. In this study, the CR for all the constructs were above the threshold value of 0.7 (ranging from 0.75 to 0.97). As a result, these values indicated high reliability for all the constructs. AVE quantifies the amount of variance captured by a construct to the variance resulting from measurement error (Dos Santos and Cirillo, 2021). Nusair and Hua (2010) suggested that when AVE is greater than 0.5, the indicators genuinely represent the latent construct. In this study, the AVE for each latent variable was greater than 0.5. The results for the measurement model are stated in Table 1 below.

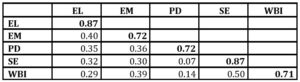

Table 1: Results for Measurement Model

Note: WBI = Whistleblowing intention, SE= Self-efficacy, EM= Empathy, EL= Ethical leadership, PD= Power distance

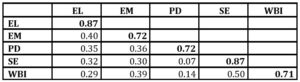

Discriminant validity is a test to ensure a measure is not highly correlated with other measures that are supposed to be different (Campbell, 1960). As the second validity evaluation in PLS path measurement, discriminant validity ensures that two conceptually different concepts reveal equate differences (Henseler, Ringle and Sinkovics, 2009). Discriminant validity will be evaluated via cross-loadings and the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Ramayah, Cheah, Ting and Memon, 2016). In satisfying the requirement of Fornell-Larcker, the comparison of construct’s AVE and squared correlations will be determined compared to other constructs in the same model (Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt, 2015). Acceptable discriminant validity is established when the AVE of each construct is higher than the construct’s highest squared correlation with any other construct in the same model, and indicator’s loadings should also be higher than all of their cross-loadings (Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt, 2012).

Based on Table 2, the AVE of each construct is higher than the correlation with any other reflectively measured latent variables. In addition, Table 2 also disclosed that the squared correlations of each construct are lower than the average variance extracted by the indicators measuring that construct. Therefore, the measurement model of this study revealed adequate discriminant validity based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Table 2: Discriminant Validity of Constructs – Fornell-Larcker Criterion

Note: WBI = Whistleblowing intention, SE= Self-efficacy, EM= Empathy, EL= Ethical leadership, PD= Power distance

Note: WBI = Whistleblowing intention, SE= Self-efficacy, EM= Empathy, EL= Ethical leadership, PD= Power distance

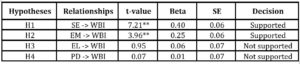

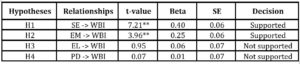

The result of the structural model supported the influence of self-efficacy on whistleblowing intention, as studies conducted by Putra and Wirasedana (2017), Hayati and Wulanditya (2018) and Bernawati and Saputra (2020). There is a significant positive relationship between self-efficacy and whistleblowing intention (β = 0.40, p < 0.01). Therefore, H1 is accepted. The significant relationship between these two constructs might explain the high confidence of respondents to report wrongdoing in their organisation. Even though whistleblowing is a complex action, high self-efficacy enhances whistleblowers’ confidence to report the misconduct effectively. Self-efficacy can activate the individuals’ self-regulatory processes that motivate them to perform complicated tasks and strive toward challenging goals (Hannah, Schaubroeck and Peng, 2016). In addition, with high self-efficacy and sufficient information, respondents have a more positive attitude that made them confident with their ability and believe in themselves to whistleblow.

This study proved a significant positive relationship between empathy and whistleblowing intention, as Hildebrand and Shawver (2016) and Gupta and Bhal (2020) found. There is a significant positive relationship between empathy and whistleblowing intention (β = 0.25, p < 0.01), hence H2 was supported. Highly empathetic employees are more likely to whistleblow as whistleblowing may benefit the organisation (Brown et al., 2010). Empathy can be characterised as a psychological force for helping others in distress via feeling and imagination of others’ emotional experiences (Erickson, Backhouse and Carless, 2017). Empathy may motivate behavioural reactions to help and protect people in vulnerable situations (Pfattheicher, Petersen and Böhm, 2020) associated with positive moral emotions identical to the perceived welfare of others (Pohling, Bzdok, Eigenstetter, Stumpf and Strobel, 2016).

There was no significant positive relationship (β = 0.06) between ethical leadership and whistleblowing intention, which was opposed to the finding of studies conducted by Zhang et al. (2016), Cheng et al. (2019) and Rabie and Malik (2020). As a result, H3 is not supported. Ethical leaders shall influence ethical climates in an organisation, consequently reducing unethical behaviour (Aryati, Sudiro, Hadiwidjaja and Noermijati, 2018). Leaders’ behaviours shape the organisation’s policies and procedures since the way leaders compensate or disregard unethical behaviours becomes a principle of practice in the organisation (Hechanova and Manaois, 2020). In this study, the insignificant relationship between ethical leadership and whistleblowing intention might explain that the ethical leader is not the main contributor to encouraging whistleblowing intention. The insignificant result of this study may also question the leader’s ethical judgment that should significantly motivate employees’ ethical behaviour (Alpkan, Karabay, Şener, Elci and Yıldız et al., 2020). Respondents might not trust their leaders’ actions, particularly actions that may reduce the adverse effect of wrongdoing reporting.

This study also revealed no significant negative relationship (β = 0.01) between power distance and whistleblowing. Hence, H4 is not supported. This finding may indicate that power distance may not influence the likelihood of whistleblowing among respondents, even though Malaysia was identified with high power distance. In contrast, a study conducted in Indonesia by Pangestu and Rahajeng (2020) found a significant negative relationship between power distance and whistleblowing intention. The same finding was also proved by Puni and Anlesinya (2017) in examining the influence of power distance on whistleblowing propensity in Africa. Even though there was no significant influence of power distance on whistleblowing intention, there was a positive coefficient between these two variables. This finding may indicate that the respondents perceived low power distance in public sector internal audit departments. Low power distance makes the employees more likely to whistleblow. Moreover, top management is willing to accept negative feedback from its employees. The following table summarises the results of the structural model of this study. Meanwhile, Figure 1 demonstrates the structural model of this study.

Table 3: Results of Structural Model

Figure 1: Structural Model

Conclusion

This study aims to determine the influencing factors of whistleblowing intention among Malaysian public sector internal auditors. The results reveal that self-efficacy and empathy influence whistleblowing intention. Meanwhile, ethical leadership and power distance are not significant contributors to whistleblowing intention. This study was also conducted using a large number of Malaysian samples. Therefore, the results may significantly contribute to the literature on whistleblowing intention among public sector internal auditors in Malaysia, which is still scarce. More whistleblowing studies are encouraged to develop an improved conceptual foundation in whistleblowing studies (Tavakoli, Keenan, and Cranjak-Karanovic, 2003). Ismail, Raja Mamat and Hassan (2018) also suggested inconclusive findings in determining the factors that influence the whistleblowing practice in Malaysia.

This study will contribute to the accounting literature in Malaysia that examines the factors that influence whistleblowing intention among Malaysian public sector internal auditors. Among recent research that inspired this study to determine the influence of the research variables on whistleblowing intention are 1) Self-efficacy: There is continuous scientific debate on the impact of self-efficacy in completing a complex task, such as whistleblowing practice (Rustiarini, Yuesti, and Dewi, 2021), 2) Empathy: Ficther (2017) recommended future studies to explore the influence of empathy on ethical decision making, whereas Hildebrand and Shawver (2016) claimed that their study was the first study examining the impact of empathy on whistleblowing intention, 3) Ethical leadership: Lee, Choi, Youn and Chun (2017) claimed that their study was the first study that examined the effect of ethical leadership on moral voice, while Andrey Hasiholan Andrey Hasiholan, Purwaka, Albert and Basid (2020) proposed more studies to evaluate the impact of ethical leadership on employee ethical behaviour and fraud detection and 4) Power distance: Brody, Gupta and Turner (2020) encouraged more studies to delve into the role of power distance on whistleblowing behaviour and Gilreath (2019) recommended the influence of power distance in developing whistleblowing programs.

Determination of the factors that increase the likelihood of whistleblowing is vital in helping the management have a clear direction to encourage whistleblowing practice. The findings of this study would propose the significant elements that result in the effective implementation of whistleblowing procedures within public sector organisations. The significant elements also help to develop the internal auditors’ ethics training and seminars conducted by the National Audit Department, Accountant General Department, The Institute of Internal Auditors Malaysia (IIAM), Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, Corporate Integrity System Malaysia (CISM) and Internal Audit Capability Model (IACM). The findings of this study may also provide practical guidance for these authorities in designing suitable policies and practices to enhance the propensity of internal auditors to report wrongdoings. It can also improve the ethical and professional standards of Malaysia’s public sector auditing profession. This is significant to improve the public trust that internal auditors carry out their duties to the best of their abilities and safeguard the public’s interest.

A whistleblowing system is a well-known approach in fraud prevention (Pamungkas, Ghozali and Achmad, 2017). Therefore, by focusing on the whistleblowing intention of internal auditors, this study may contribute to understanding the critical roles of internal auditors in dealing with unethical behaviour and fraud issues. International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing, Standard 1220.A1 requires internal auditors to exercise due professional care through governance effectiveness, risk management, probability of significant errors, fraud and noncompliance. In addition, Standard 2060 briefed on the content of internal auditors reporting that includes significant risk and control issues, including fraud risks, governance issues, and other matters that require management’s attention. Even though it is not the responsibility of internal auditors to detect fraud, they should be equipped with reasonable skills and knowledge in detecting and reporting malpractices or fraud issues in their organisation (Alias, Nawawi and Salin, 2019).

Despite the study’s contributions discussed above, several limitations need to be concerned. In this study, a self-reported questionnaire was used to examine the whistleblowing intention among internal auditors. Using a self-reported questionnaire means all the data were attained from a single source, the study’s respondents. In this study, the decision to whistleblow or not to whistleblow relies on the internal auditors’ perceptions of whistleblowing. There is a possibility some respondents perceived themselves as heroic and more courageous to whistleblow than others. As a result, the decision to whistleblow indicates the individual’s experience, which can be obtained by asking about the internal auditor’s whistleblowing intention. Therefore, the results of this study rely on the truthful, accuracy and honesty of the respondents in answering the questionnaire. The absence of honest answers may threaten the validity and generalisability of the findings.

Whistleblowing is a controversial issue as it involves revealing secret information (Lindblom, 2007). Disclosing sensitive information leads to negative consequences for whistleblowers (Abbas and Ashiq, 2020), such as fear of retaliation, stress and pressure and even life-threat. Exploring whistleblowing behaviour is associated with a high level of study’s sensitivity. Some people might feel irritated or uncomfortable explaining their actual whistleblowing action. Delving into a whistleblowing study is complicated as it is always associated with serious misbehaviour issues (Miceli and Near, 1984). Investigation about immoral behaviour in the actual organisations is difficult to be conducted (Chiu. 2003). Whistleblowers may withhold certain information since they are concerned about their confidentiality or anonymity in revealing their actual whistleblowing behaviour (Sims and Keenan, 1998). Hence, in this study, the data were gained to conclude the whistleblowing behaviour using whistleblowing intentions rather than actual whistleblowing.

Measuring intention will produce inaccurate information explaining the actual whistleblowing behaviour among the internal auditors. Examination of perceptions instead of real action will reduce the richness of describing the actual situation (Seifert, Sweeney, Joireman and Thornton et al., 2010). The respondents’ intention may draw a different conclusion regarding real situations. As a result, the findings of this study may not represent the actual whistleblowing of the whole population of Malaysian public sector internal auditors. Internal auditors who responded that they would blow their whistle may not truly do it. Nevertheless, previous studies supported the theoretical relationship between moral intention and moral behaviour (Victor, Trevino and Shapiro, 1993).

The insignificant relationship between power distance and whistleblowing intention raises interesting questions about why no significant relationship existed. One potential answer could establish that modification is needed for the employed items measure suitable for the Malaysian public sector setting. Therefore, this study proposes that future research use more suitable cultural dimensions that could probably be occupied based on the inferred relationships from other studies in Asian countries. Study for more suitable cultural dimensions should be an exciting avenue for future empirical research. A study that determines the influencing factors of whistleblowing intention requires ongoing exploration of additional variables related to the organisation’s ethical decision-making. Many other factors may influence whistleblowing intention in the public sector. Possible factors are the relationship between wrongdoer and whistleblower, the influence of individuals’ political ideology, whistleblowing policy, enforcement staff or ethics hotline.

References

- Abbas, N., & Ashiq, U. (2020). Why I don’t blow the whistle? Perceived barriers by the university teachers to report wrong doings. Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (LASSIJ), 4(2), 84-97.

- Abdul, S. L. M. M. S., Yusoff, H., & Mohamed, N. (2019). Factors that might lead to corruption: A case study on Malaysian government agency. International Journal of Financial Research, 10(3), 216-229.

- Ahmad, N., Othman, R., Othman, R., & Jusoff, K. (2009). The effectiveness of internal audit in Malaysian public sector. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 5(9), 53.

- Ahmad, SA (2011). Internal auditor and internal whistleblowing intentions: A study of organisational, individual, situational and demographic factors. [Online], [Retrieved September 10, 2021], http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/152

- Alias, N. F., Nawawi, A., & Salin, A. S. A. P. (2019). Internal auditor’s compliance to code of ethics: Empirical findings from Malaysian government-linked companies. Journal of Financial Crime. 26 No. 1, 2019 pp. 179-194.

- Allegrini, M., D’Onza, G., Paape, L., Melville, R., & Sarens, G. (2006). The European literature review on internal auditing. Managerial Auditing Journal.

- Alpkan, L., Karabay, M., Şener, İ., Elci, M., & Yıldız, B. (2020). The mediating role of trust in leader in the relations of ethical leadership and distributive justice on internal whistleblowing: A study on Turkish banking sector. Kybernetes.

- Anggraini, F. R. R., & Siswanto, F. A. J. (2016). The role of perceived behavioral control and subjective norms to internal auditors’ intention in conveying unethical behavior: A case study in Indonesia. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 5(2), 141.

- Arifin, M. A. M., & Ahmad, A. H. (2017). Kepentingan budaya integriti dan etika kerja dalam organisasi di Malaysia: Suatu tinjauan umum. Geografia-Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 12(9).

- Aryati, A. S., Sudiro, A., Hadiwidjaja, D., & Noermijati, N. (2018). The Influence of ethical leadership to deviant workplace behavior mediated by ethical climate and organisational commitment. International Journal of Law and Management.

- Ayagre, P. (2015). Internal audit capacity to enhance good governance of public sector organisations: Developing countries perspective. Journal of Governance and Development, 11(1), 39-60.

- Bashir, S., Khattak, H. R., Hanif, A., & Chohan, S. N. (2011). Whistleblowing in public sector organisations: Evidence from Pakistan. The American Review of Public Administration, 41(3), 285-296.

- Bernawati, Y., & Saputra, R. S. (2020). The effect of individual factors, subjective norms, and self-efficacy on the intention of whistleblowing. Public Management and Accounting Review, 1(1), 20-31.

- Bilal, Z. O., Twafik, O. I., & Bakhit, A. K. (2018). The influence of internal auditing on effective corporate governance in the banking sector in Oman. European Scientific Journal, 18, 257-271.

- Brody, R. G., Gupta, G., & Turner, M. (2020a). The influence of country of origin and espoused national culture on whistleblowing behavior. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management. V 29 No. 2, 2021, pp. 228-246.

- Brown, T. A., Sautter, J. A., Littvay, L., Sautter, A. C., & Bearnes, B. (2010). Ethics and personality: Empathy and narcissism as moderators of ethical decision making in business students. Journal of Education for Business, 85(4), 203-208.

- Campbell, D. T. (1960). Recommendations for APA test standards regarding construct, trait, or discriminant validity. American Psychologist, 15(8), 546–553.

- Cheisviyanny, C., & Arza, F. I. (2019, April). Whistleblowing intention of internal governmental auditors in Padang. Proceedings of the 2nd Padang International Conference on Education, Economics, Business and Accounting (PICEEBA-2 2018), Atlantis Press, 24-25 November 2018, West Sumatera, Indonesia, 1-10.

- Cheng, J., Bai, H., & Yang, X. (2019). Ethical leadership and internal whistleblowing: A mediated moderation model. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(1), 115-130.

- Chiu, R. K. (2003). Ethical judgment and whistleblowing intention: Examining the moderating role of locus of control. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(1), 65-74.

- Darjoko, F. J., & Nahartyo, E. (2017). Efek tipe kecurangan dan anonimitas terhadap keputusan investigasi auditor internal atas tuduhan whistleblowing. Jurnal Akuntansi Dan Keuangan Indonesia, 14(2), 202-221.

- Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85.

- Diana, D., & Nicolae, B. (2012). How is the future for the internal auditing? Economic Sciences Series, 1398.

- Dorfman, P. W., & Howell, J. P. (1988). Dimensions of national culture and effective leadership patterns: Hofstede revisited. Advances in International Comparative Management, 3(1), 127-150.

- Dos Santos, P. M., & Cirillo, M. Â. (2021). Construction of the average variance extracted index for construct validation in structural equation models with adaptive regressions. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, 1-13.

- Ede, A., Sullivan, P. J., & Feltz, D. L. (2017). Self-doubt: Uncertainty as a motivating factor on effort in on exercise endurance task. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 28, 31-36.

- Erickson, K., Backhouse, S. H., & Carless, D. (2017). “I don’t know if I would report them”: Student-athletes’ thoughts, feelings and anticipated behaviours on blowing the whistle on doping in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 30, 45-54.

- Fichter, R. D. (2017). Do the right thing! Exploring ethical decision-making in financial institutions (Doctoral dissertation, Teachers College, Columbia University). [Online], [Retrieved September 10, 2021],https://media.proquest.com/media/hms/ORIG/2/dtx5K?_s=cT%2BRcl4EwL7Q2igQWD3WomoGxHM%3D

- Gilreath, R. C. (2019). Investigating cultural effects on whistleblowing concerning fraud: A quantitative study (Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University). [Online], [Retrieved September 10, 2021],https://www.proquest.com/openview/761e1d434129dde4dc4cd4f13ff03771/1?pq origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Gupta, S., & Bhal, K. T. (2020). Reporting misdemeanors in the workplace: Analysing enablers using modified TISM approach. The TQM Journal.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 1(46), 1-12.

- Hamoudah, M. M., Othman, Z., Abdul Rahman, R., Mohd Noor, N. A., & Almoudi, M. (2021). Ethical leadership, ethical climate and integrity violation: A Comparative study in Saudi Arabia and Malaysia. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 43.

- Hannah, S. T., Schaubroeck, J. M., & Peng, A. C. (2016). transforming followers’ value internalisation and role self-efficacy: Dual processes promoting performance and peer norm-enforcement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 252.

- Hayati, N., & Wulanditya, P. (2018). Attitudes towards whistleblowers, organisational commitment, ethical climate principles, and self-efficacy as determinants of fraud disclosures. The Indonesian Accounting Review, 8(1), 25-35.

- Hechanova, M. R. M., & Manaois, J. O. (2020). Blowing the whistle on workplace corruption: The role of ethical leadership. International Journal of Law and Management.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2012). Using partial least squares path modeling in advertising research: Basic concepts and recent issues. In Handbook of Research on International Advertising. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hildebrand, J., & Shawver, T. J. (2016). The impact of empathy and selfism on whistleblowing intentions. Journal of Accounting, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 17, No. 3 (2016).

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Recent Consequences: Using dimension scores in theory and research. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 1(1), 11–17.

- Hsiung, H. H., & Tsai, W. C. (2017). The joint moderating effects of activated negative moods and group voice climate on the relationship between power distance orientation and employee voice behavior. Applied Psychology, 66(3), 487-514.

- Humantito, I. J. (2017). Whistleblowing decisions in responding to organisational corruption in government internal audit units in Indonesia (Doctoral dissertation, University of Warwick). [Online], [Retrieved September 10, 2021],http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/86747/1/WRAP_Theses_Humantito_2016.pdf

- Hyland, P., Boduszek, D., Dhingra, K., Shevlin, M., & Egan, A. (2014). A Bifactor approach to modelling the Rosenberg self esteem scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 66, 188-192.

- Ismail, A. M., Raja Mamat, R. M. S., & Hassan, R. (2018). The influence of individual and organisational factor on external auditor whistleblowing practice in government-linked companies (GLC’S). Asia-Pacific Management Accounting Journal (APMAJ), 13(1), 231-266.

- Ismail, S., & Yuhanis, N. (2018). Determinants of ethical work behaviour of Malaysian public sector auditors. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration.

- Kahyaoglu, S. B., & Caliyurt, K. (2018). Cyber security assurance process from the internal audit perspective. Managerial Auditing Journal.

- Kuncara W, A., Furqorina, R., & Payamta, P. (2017). Determinants of internal whistleblowing intentions in public sector: Evidence from Indonesia. In SHS Web of Conferences(Vol. 34).

- Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader–follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47-57.

- Lindblom, L. (2007). Dissolving the moral dilemma of whistleblowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 76(4), 413-426.

- Liu, S. M., Liao, J. Q., & Wei, H. (2015). Authentic leadership and whistleblowing: mediating roles of psychological safety and personal identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(1), 107-119.

- MACC (2021). Civil servants vital in eradicating corruption. [Online], [Retrieved September 10, 2021], https://www.sprm.gov.my/index.php?page_id=103&contentid=1789&cat=CN&language=en.

- MacNab, B. R., & Worthley, R. (2008). Self-efficacy as an intrapersonal predictor for internal whistleblowing: A US and Canada examination. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(4), 407-421.

- Malik, M. S., & Nawaz, M. K. (2018). The role of ethical leadership in whistleblowing intention among bank employees: Mediating role of psychological safety. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, Vol. 7, Supplementary Issue 4.

- Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of Ethical Climate Theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 175-194.

- Miceli, M. P. and Near, J. P. (1984). The relationships among beliefs, organisational position, and whistleblowing status: A discriminant analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 27(4), 687-705.

- Myyry, L., & Helkama, K. (2001). University students’ value priorities and emotional empathy. educational psychology, 21(1), 25-40.

- Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1985). Organisational dissidence: The case of whistleblowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 4(1), 1-16.

- Nusair, K., & Hua, N. (2010). Comparative assessment of structural equation modeling and multiple regression research methodologies: E-commerce context. Tourism Management, 31(3), 314-324.

- Orhan, U., and Ozyer, K. (2016). I whistleblow as i am a university student: An investigation on the relationship between self-efficacy and whistleblowing. International Journal of Business Administration and Management Research, 2(1), 28-33.

- Pamungkas, I. D., Ghozali, I., & Achmad, T. (2017). The effects of the whistleblowing system on financial statements fraud: Ethical behavior as the mediators. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 8(10), 1592-1598.

- Pangestu, F., & Rahajeng, D. K. (2020). The effect of power distance, moral intensity, and professional commitment on whistleblowing decisions. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business (JIEB), 35(2), 144-162.

- Park, H., Blenkinsopp, J., Oktem, M. K., & Omurgonulsen, U. (2008). Cultural orientation and attitudes toward different forms of whistleblowing: A comparison of South Korea, Turkey, and the UK. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 929-939.

- Park, H., Rehg, M. T., & Lee, D. (2005). The influence of Confucian ethics and collectivism on whistleblowing intentions: A Study of South Korean Public Employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 58(4), 387-403.

- Pfattheicher, S., Petersen, M. B., & Böhm, R. (2020). Information about herd immunity and empathy promote COVID-19 vaccination intentions. In press at Health Psychology.

- Pohling, R., Bzdok, D., Eigenstetter, M., Stumpf, S., & Strobel, A. (2016). What is ethical competence? The role of empathy, personal values, and the five-factor model of personality in ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(3), 449-474.

- Puni, A., & Anlesinya, A. (2017). Whistleblowing propensity in power distance societies. Journal of Global Responsibility, 8(2), 212-224.

- Puni, A., & Hilton, S. K. (2020). Power distance culture and whistleblowing intentions: The moderating effect of gender. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 36(2), 217–234.

- Putra, I. M. D. D., & Wirasedana, I. W. P. (2017). Pengaruh komitmen profesional, self-efficacy, dan intensitas moral terhadap niat untuk melakukan whistleblowing. E-Jurnal Akuntansi Universitas Udayana, 21(2), 1488-1518.

- Rabie, M. O., & Malek, M. A. (2020). Ethical leadership and whistleblowing: Mediating role of stress and moderating effect of interactional justice. SEISENSE Journal of Management, 3(3), 1-11.

- Rachagan, S., and Kuppusamy, K. (2013). Encouraging whistle blowing to improve corporate governance? A Malaysian initiative. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(2), 367-382.

- Ramayah, T. Cheah, J., Ting, F.C.H and Memon, M.A. (2016). Partial least square structural equation modeling (pls-sem) using smartpls 3.0, an updates and practical guide to statistical analysis. 1st Pearson Malaysia Sdn. Bhd.

- Rogers, J. D., Clow, K. E., & Kash, T. J. (1994). Increasing job satisfaction of service personnel. Journal of Services Marketing.

- Rustiarini, N. W., Yuesti, A., & Dewi, N. P. S. (2021). Professional commitment and whistleblowing intention: The role of national culture. Jurnal Reviu Akuntansi dan Keuangan, 11(1).

- Seifert, D. L., Sweeney, J. T., Joireman, J., and Thornton, J. M. (2010). The influence of organisational justice on accountant whistleblowing. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 35(7), 707-717.

- Shafer, W. E. (2008). Ethical climate in Chinese CPA firms. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 33(7-8), 825-835.

- Shafer, W. E., Simmons, R. S., & Yip, R. W. (2016). Social responsibility, professional commitment and tax fraud. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal.

- Sharif, Z. (2015). Intention towards whistleblowing among internal auditors in the UK (Doctoral dissertation, University of Huddersfield). [Online], [Retrieved September 10, 2021], http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/28421/1/Final%20thesis%20-%20SHARIF.pdf

- Sims, R. L., & Keenan, J. P. (1998). Predictors of external whistleblowing: Organisational and intrapersonal variables. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(4), 411-421.

- Tavakoli, A. A., Keenan, J. P., and Cranjak-Karanovic, B. (2003). Culture and whistleblowing an empirical study of Croatian and United States managers utilising Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(1-2), 49-64.

- Tavousi, M., Hidarnia, A. R., Montazeri, A., Hajizadeh, E., Taremian, F., & Ghofranipour, F. (2009). Are perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy distinct constructs? European Journal of Scientific Research, 30(1), 146-152.

- The Star (2018). TIM: corruption has cost the country 4% of GDP value annually, [Online], [Retrieved September 10, 2021], https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2018/05/26/tim-corruption-has-cost-the-country-4-of-gdp-value-annually/.

- Valentine, S., & Godkin, L. (2019). Moral intensity, ethical decision making, and whistleblowing intention. Journal of Business Research, 98, 277-288.

- Victor, B. and Cullen, J.B. (1988), “The organisational bases of ethical work climates”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 33 No. 1, pp. 101-125.

- Victor, B., Trevino, L. K., & Shapiro, D. L. (1993). Peer reporting of unethical behavior: The influence of justice evaluations and social context factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(4), 253-263.

- Yuliani, A., Kusumah, Y. S., & Sumarmo, U. (2019). Mathematical creative problem solving ability and self-efficacy:(A Survey With Eight Grade Students). In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1157, No. 3, p. 032097). IOP Publishing.

- Zahari, A. I., Said, J., & Muhamad, N. (2021). Public sector fraud: The Malaysian perspective. Journal of Financial Crime.

- Zakaria, M., Razak, S. N. A. A., and Yusoff, M. S. A. (2016). The Theory of Planned Behaviour as a framework for whistleblowing intentions. Review of European Studies, 8(3), 221.

- Zhang, F. W., Liao, J. Q., & Yuan, J. M. (2016). Ethical leadership and whistleblowing: Collective moral potency and personal identification as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44(7), 1223-1231.