Introduction

This article focuses on one of the most significant and common issues in profit distribution within business groups listed on the Lima Stock Exchange. The way these businesses operate is remarkable, as they no longer compete solely with local companies but must also contend with global enterprises. To thrive in this competitive landscape, companies need to strengthen themselves with various strategies, one of which involves establishing multiple legally independent companies under the financial and operational control of a parent company (the holding company). In other words, a controlling entity and several subsidiary companies. However, global corporations like Amazon have been reported to curtail workers’ labor rights, making concerted efforts to prevent collective empowerment, such as the formation of labor unions.

In this context, current legislation in Peru allows for the formation of business groups. However, from time to time, we come across news reports of workers within these groups raising complaints of labor law violations.

Within our scope of study, focusing on the Backus business group, as highlighted by former congresswoman Indira Huilca in her blog post dated April 12, 2018, she states: “It is particularly concerning that one of the largest companies in the country, which generates significant profits for its owners, engages in anti-union practices (such as non-compliance with collective bargaining agreements) and fosters conditions that affect the safety and health of its personnel (poor food service). This situation not only infringes upon labor rights but also violates principles and rules outlined in the Code of Conduct of Anheuser-Busch InBev (AB InBev), the owner of Unión de Cervecerías Peruanas Backus y Johnston.”

In terms of retrospective studies considered for this research, Rojas (2016) conducted a study titled “The Evolution of Business Groups in Labor Law in Chile: From Irrelevance to Law No. 20,760 of 2014.” In his final observations, Rojas highlights several key points. Firstly, he notes that the recognition of business groups in labor law within the legal framework was rather delayed. Secondly, in the Chilean legal system, a jurisprudential doctrine was developed and solidified, recognizing business groups as a single entity based on their configuration as an economic unit. Finally, Law No. 20,760 of 2014 established a specific legal framework regarding the labor effects of business groups.

Similarly, at the national level in Peru, Cravero (2014) conducted a study titled “Solidarity Liability” of fraudulent business groups, and reached the following conclusions. Despite the absence of explicit regulations regarding business groups in our current labor legislation, this has not prevented our judges from determining when, in contrast to the existence of a genuine group, they are dealing with a fraudulent business group. It has also been observed that in cases of fraudulent business groups, the concept of solidarity liability does not apply. Strictly speaking, this concept requires a plurality of debtors equally obligated to the worker’s credits. In these cases, it would be appropriate to attribute the responsibility to a single debtor with multiple faces, as expressed by Ermida.

Similarly, in the regional context, Chuquiruna (2017) was taken into consideration with their research titled “Principles of Law that Demonstrate the Impact on the Constitutional Right of Workers to Participate in Profits within Business Groups in Peru.” Chuquiruna asserts that independent legal personality grants commercial entities their own capacity and complete autonomy, assuming rights and obligations. However, the fraudulent use of this legal personality by certain business groups infringes upon rights such as the constitutional right of workers to participate in profits. The limitation of liability for legal entities is justified, as it provides reassurance to investors who risk their capital in a business. Nevertheless, there are companies that are part of fraudulent business groups, taking advantage of this right and committing fraud against the law, thereby detrimentally affecting workers’ right to participate in the profits generated by the company they work for.

Therefore, regarding the conceptual foundations of this research, we start with business groups, which are crucial for the country as they primarily contribute to tax revenue and job creation. According to Article 59 of the Peruvian Political Constitution (1993), it is the duty of the State to stimulate wealth creation and guarantee freedom of work, freedom of enterprise, commerce, and industry. Organizational freedom is a key aspect of economic freedom (Kresalja & Ochoa, 2016). It includes the choice of business objectives or activities, company name, registered address, type of business entity (sole proprietorship, limited liability company, individual limited liability company), or type of commercial entity (limited liability company, closed joint-stock company, open joint-stock company, civil company, partnership) or nonprofit organization (association, foundation). It also encompasses decisions regarding the authority of administrators, pricing policies for products and/or services, credit and insurance, employee hiring, and the creation of business groups that help companies generate value for their customers.

Meanwhile, Khanna and Yafeh (2007) argue that business groups operate under economic conditions and can sometimes act as “paragons” and other times as “parasites” from a welfare perspective. One of their observations is that the formation of diverse and diversified economic groups tends to occur more frequently in less developed markets. They associate this trend with factors such as minimal government regulations, unclear labor laws, a desire to minimize taxes, and limited development of employee competencies and skills.

Similarly, Vilches and Rodríguez (2016) mention that business groups, with their structures of parent companies, subsidiaries, subordinates, and affiliates, built over time through diversification processes, are prevalent in the national economy. They highlight that conglomerates in Colombia are thriving, serving as major employers in the country, and expanding their areas of influence internationally based on their diversification strategies.

Regarding the financial information obtained from the Superintendencia del Mercado de Valores (SMV), Unión de Cervecerías Peruanas Backus y Johnston S.A.A. is an indirect subsidiary of Anheuser-Busch InBev NV/SA, a company based in Belgium. Anheuser-Busch InBev NV/SA owns 97.33% of the issued capital through various subsidiaries. Unión de Cervecerías Peruanas Backus y Johnston S.A.A. functions as the parent company of an economic group in Peru, which comprises several subsidiaries including Cervecería San Juan S.A., Transportes 77 S.A., Naviera Oriente S.A.C., Inmobiliaria IDE S.A., Backus Marcas y Patentes S.A.C., Backus Servicios de Ventas S.A., Backus Estrategia S.A.C., Backus Ya S.A.C., Distribuidora San Ignacio S.A.C., Distribuidora Coronel Portillo S.A.C., and Fundación Backus.”

Among these subsidiaries, Cerveceria San Juan S.A. is engaged in a similar line of business, while two subsidiaries are dedicated to the transportation of the group’s products. The remaining subsidiaries are involved in complementary activities.

As we can see in the table, business groups engage in various economic activities, which can be formed through the acquisition of existing companies, the creation of new companies, or the merger of existing companies. The advantage of a business group is that companies can benefit from economies of scale, share resources and knowledge, and have a greater capacity to diversify their activities and mitigate risks. However, there are also challenges associated with managing a business group, such as the need to balance the interests and goals of the different constituent companies and ensure effective coordination and communication among them.

For this reason, Arce (2008) emphasizes the importance of focusing on the plurality of companies rather than just the legal plurality, as legal plurality can mask fraudulent groups. These false groups aim to arbitrarily fragment a single business activity into different legal entities. Therefore, the requirement of legal personality in companies that form a business group is a necessary formal requirement, although not sufficient to determine the presence of a business group. The author also highlights another problem, which is identifying the true employer of workers who work for business groups. This issue arises when companies employ complex structures to evade labor responsibilities and reduce costs.

In business groups, it is possible that workers are employed by a different company than the one they work for, making it difficult to identify the true employer. This situation can lead to issues regarding labor rights, as the actual employer may not be fulfilling their legal obligations, such as payment of wages, social benefits like profit sharing, and social security contributions.

Regarding the issue of profit sharing for workers, it can be mentioned that the participation of workers in company profits has similarities and differences worldwide. For instance, Moreno (2015) concludes that an examination of the constitutional framework for workers’ economic participation in the company, as reflected in the constitutions of Spain and Argentina, reveals that although both constitutional norms address workers’ participation, the regimes they establish differ significantly in matters such as the recognition of participation as a right, the structure of the norm as a binding rule or a principle, the content of participation, its direct effectiveness, and the possibility of demanding specific actions from public authorities.

Additionally, in Peru, Article 29 of the Political Constitution of Peru (1993) states that the State recognizes the right of workers to participate in company profits. Therefore, worker participation in company profits is a labor right established by law that allows workers to share in the earnings generated by the company they work for.

The above is corroborated by Ferro (2019), who mentions that this right allows the worker to share in the profits obtained by the company and helps align the interests of the employer and the worker, leading to better economic results at the end of each financial period. Therefore, it is considered an important labor benefit, particularly in companies with substantial profits, as it can amount to up to eighteen monthly salaries. This means that the profit sharing can exceed the sum of the other compensation elements the worker receives for their personal service (12 monthly salaries, 2 bonuses, and severance pay).

It is important to note that workers’ participation in profits is regulated by several laws and regulations in Peru. These include:

Legislative Decree No. 677 (1991): Regulates the participation in profits, management, and ownership of workers in companies engaged in income-generating activities of the third category and subject to private sector labor regulations.

Legislative Decree No. 892 (1996): Regulates the right of workers to participate in the profits of companies engaged in income-generating activities of the third category.

Law No. 28873 (2006): Law that repeals Supreme Decree No. 003-2006-TR and specifies Article 4 of Legislative Decree No. 892.

Supreme Decree No. 009-98-TR (1998): Regulation for the implementation of the right of private sector workers to participate in the profits generated by the companies where they render services.

These legal instruments provide the framework and guidelines for the implementation and enforcement of workers’ participation in profits in Peru.

According to Article 9 of Legislative Decree No. 677 (1991), companies obligated to distribute profits to their workers are income-generating companies classified under the third category, with the exception of cooperatives, self-managed companies, civil partnerships, and companies with fewer than twenty (20) employees.

To determine whether a company exceeds or falls within the twenty-worker limit, Article 2 of Supreme Decree No. 009-98-TR (1998) specifies the following calculation: the number of workers, regardless of the type of employment contract, who have worked in the company each month, is summed up for all twelve months. The total is then divided by 12, and if the result is 20.5 or higher, the company is obligated to distribute profits to its workers.

The amount of profit sharing is calculated based on the Net Income of the third category determined according to the Income Tax Law and its Regulation, after deducting previous tax losses, depending on the company’s main activity:

- a) 10% for fishing, telecommunications, and industrial companies.

- b) 8% for mining, wholesale and retail trade, and restaurant companies.

- c) 5% for companies engaged in other types of activities.

The amount to be distributed as workers’ profits will be calculated based on the Net Income (adjusted accounting result with additions and deductions), after offsetting previous tax losses according to the Income Tax Law and its Regulation. However, this calculation should not include the deduction of workers’ participation in profits. The distribution of the calculated amount will follow the following guidelines:

- a) 50% of the amount will be distributed based on the days worked by each worker.

- b) The remaining 50% will be distributed based on the remuneration received by each worker.

In the event that there is a surplus between the amount calculated based on point b and the limit of 18 monthly salaries, this surplus must be transferred to the National Labor Training and Employment Promotion Fund.

Regarding business groups and their labor effects, we can indicate that they can have various labor effects, both positive and negative, such as:

- a) Labor synergies: One positive effect of business groups is the possibility of generating labor synergies.

- b) Job reorganization: Business groups often seek to optimize their structure and processes, which can lead to job reorganization.

- c) More precarious labor contracts: Business groups can also have a negative effect on workers if they are used to create more precarious labor contracts or to outsource jobs through labor intermediation or outsourcing. In some cases, companies may use employment contracts through a subsidiary or affiliate to reduce labor costs and avoid the application of certain labor laws, such as Legislative Decrees 677 and 892, Law 28873, as well as Supreme Decree 009-98-TR, which regulate the participation in profits generated by the company during the period.

- d) Concentration of business power: Another potential negative consequence of business groups is the concentration of business power. If a business group has significant holdings and control in various economic sectors, it can exert significant influence in labor markets, which can be detrimental to workers if remuneration and working conditions are not appropriate.

However, this lack of legal and conventional attention to the figure of the business group as an employer, which openly contrasts with the proliferation in recent years of special laws outside the labor sphere, is generating significant legal problems in the new socio-economic reality that demand responses from the legal framework.

Methodology

Considering the methodological aspect, the present study adopts the perspective of the phenomenological paradigm with a basic typology, which, according to Hernández (2016), involves the registration, analysis, and interpretation of current nature. In this study, each category was analyzed to subsequently describe and expand the knowledge.

The study also employed a qualitative-quantitative approach, also known as a mixed-methods approach, which, according to Rodríguez (2005), involves the combination of description, analysis, and interpretation of categories along with numerical or percentage data.

Furthermore, the study adopts a non-experimental design, which, according to Kerlinger (1981), means that in non-experimental research, it is impossible to manipulate variables. Instead, this research solely focused on seeking judicial resolutions of business groups that have committed fraud to the law and analyzing them as they are.

Similarly, this research employs a longitudinal approach, which, according to Hernández (2016), involves gathering information at multiple points in time. Therefore, the investigation starts with a factual-perceptible aspect or diagnostic approach, leading us to analyze and validate the research purpose.

Regarding the population, it consists of 217 business groups listed on the Lima Stock Exchange as corporate groups. For the sample selection, a convenience sampling method was employed, choosing the Backus corporate group, from which we have obtained judicial resolutions for non-payment of profits.

Regarding data collection, the technique used was document analysis, and the instrument used was the examination of judicial resolutions, specifically analyzing the rulings from the Peruvian Judicial System.

Finally, the method employed was Inductive-Deductive, through which knowledge about the behavior of the variables involved in our research objective was obtained, allowing us to support statements regarding our study objects.

Findings

The obtained findings were analyzed based on the research objectives and hypotheses. This was done to determine if there are business groups that defraud the Law on workers’ profit sharing. To gather and analyze relevant information, category tables were used, and data related to the variable were collected. The presentation and analysis of the results are shown in the following tables:

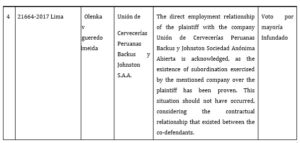

Table 1: Results at the first and second judicial instances.

From Table 1, we can see that in all 4 judicial processes, the courts ruled that the business relationships between San Ignacio SA and Unión de Cervecerías Peruanas Backus y Johnston SA are not prohibited, but on the contrary, they are allowed, as they are supported by constitutional rights such as the freedom of enterprise and private property, enshrined in Articles 59 and 70 of the Political Constitution of the State. However, they pointed out that these lawful business phenomena become relevant to labor law when they entail an impact on the sphere of labor protection. The plaintiffs requested recognition of their direct employment relationship with BACKUS and claimed payment for the concept of profits. In the cases analyzed, considering the evidence, it was examined whether the company SISA, which carried out the distribution work for BACKUS, had entrepreneurial autonomy since it

constitutes an essential requirement for the validity of commercial contracts entered into between the co-defendants. SISA did not have the necessary resources and equipment to carry out beer distribution; it did not have its own fleet of vehicles, nor did it have an independent management and technical autonomy, indicating that SISA’s involvement was limited to mere personnel provision and did not assume full responsibility for the distribution process on its own account and risk, which rules out a valid outsourcing scenario. Essentially, SISA and BACKUS were one single company. Therefore, the recharacterization of the outsourcing contract applies, which leads to the conclusion that the displaced workers from the outsourcing company have a direct and immediate employment relationship with the principal company. Regarding the reimbursement of profit sharing, it corresponds to be carried out by BACKUS.

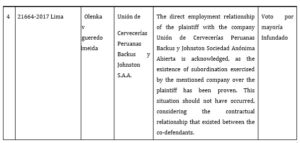

Table 2: Results at the Casation Level

From Table 2, we observe that in all 4 cases we reviewed, which reached the Supreme Court, they were all dismissed, ultimately ruling in favor of the plaintiffs. The Supreme Court highlights that in this process, the due process guidelines have been respected, and, therefore, the motivation of the judicial resolutions has been demonstrated. The Court of Appeals has conducted a comprehensive and sufficient evaluation of each item of evidence, thereby confirming the existence of an employment relationship between the plaintiffs and Backus.

Discussion

We affirm that we agree with the findings of the thesis “Main legal grounds that evidence the violation of the constitutional right of workers to participate in profits in business groups in Peru,” which means that there are indeed business groups that violate the right to profit sharing for workers. To validate the results, the following steps were followed through the observation of documents: (a) Identify relevant documents: for our research, relevant judicial resolutions regarding business groups that have affected the constitutional right of workers to participate in company profits were identified, (b) Review the documents: a thorough review of the selected resolutions was conducted to extract relevant information that could support or refute the hypothesis, (c) Analyze the extracted information: once the relevant information from the resolutions was extracted, it was analyzed and evaluated to determine if it supports or refutes what was proposed, and (d) Evaluate the validity of the documents: the source of the resolutions is the CEJ (Judicial Records Consultation) of the Judicial Power of Peru.

Conclusions

In accordance with the results obtained and the objectives pursued, we proceed to present the conclusions of this research: (1) The investigation identified that some business groups do not distribute profits legally and fairly among their workers, (2) The research confirms the hypothesis formulated at the beginning of the investigation, namely, some business groups do not legally and fairly distribute profits among their workers, (3) The impact of the lack of fair distribution of profits among workers in business groups generates job dissatisfaction and low productivity, and (4) Business groups strive to avoid disclosing the companies that form part of their conglomerates to workers and society, as it may reveal labor law violations.

References

- Arce, E. G. (2008). Individual Labor Law in Peru. Lima: Palestra Editores SAC.

- Chuquiruna Ch, G. (2017). Main legal foundations that evidence the violation of the constitutional right of workers to participate in the profits of business groups in Peru. National University of Cajamarca.

- Constitución Política del Perú. (1993).

- Cravero Cisneros, Y. (2014). “Solidary Liability” of fraudulent business groups. Peruvian Society of Labor and Social Security Law.

- Legislative Decree No. 677. (1991).

- Legislative Decree No. 892. (1996).

- Supreme Decree No. 009-98-TR. (1998).

- Ferro, V. (2019). Individual Labor Law in Peru. Lima: PUCP Publishing House.

- Hernández S, R., Fernández C, C., & Pilar L. (2016). Research Methodology. Mc Graw Hill Publishing, Colombia.

- Kresalja, B., & Ochoa, C. (2016). Economic Constitutional Law. Lima: PUCP, Fondo Editorial.

- Kerlinger, F. N. (1981). Scientific Research (1st ed.). Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamerican.

- Rodríguez, M. (2005). Qualitative Research in Marketing: The Path to a Social Perception of the Market.

- Law No. 28873 (2006).

- Rojas M, I. (2016). The Evolution of Business Groups in Chilean Labor Law: From Irrelevance to Law No. 20.760 of 2014. Revista Chilena de Derecho.