Introduction

Crises have always been and will be a part of human life, arousing interest among researchers in studying their features and consequences to successfully mitigate them (Cuny, 1994). In an educational context, across the world, the recent crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked interest in researching the powerful impetus for digitalization of the learning process (Hofer et al., 2021). At this moment, there is a plethora of studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the educational landscape all over the world. The pandemic contributed to the speedy development of online education (Bellini et al., 2021), the adoption of new digital technologies (Fenwick et al., 2021), and made educators switch to ‘pandemic-friendly’ formats such as online, blended, or hybrid learning (LeBlanc 2020). While there are reports on the successful transition and adaptation of teaching and overall positive student experiences (Cone et al. 2022), studies also reveal challenges in terms of inequities in access and experiences of digital communications (Peters et al. 2022, Berbyuk Lindström et al., 2023, Sofkova Hashemi et al., 2023).

Continuity of education in times of crisis is pivotal as education disruptions can profoundly impact future generations (Chang-Bacon, 2021). Understanding the dynamics of education delivery during times of crisis is paramount, as it offers critical insights into the adaptability and resilience of educational systems in adverse circumstances (Duchek, 2020) and its development in post-war times (Kreso, 2008). These insights serve as a linchpin for crafting effective strategies and interventions aimed at maintaining educational access, continuity, and quality when faced with disruptive events. The current state of research highlights a significant gap in understanding how education is impacted during crises other than the COVID-19 pandemic, such as conflicts or wars. While there has been extensive exploration into the effects of the pandemic on education systems worldwide, relatively little attention has been given to analyzing the unique challenges and dynamics of education in military conflicts. Military conflicts, compared to the pandemic, are typified by elevated stress levels, pervasive uncertainty, and the rigors of military operations. Military conflicts often result in substantial destruction of infrastructure, necessitate large-scale evacuations, and inflict shock and trauma on affected populations. Moreover, individuals are compelled to adapt to unconventional environments, such as working in bunkers and bomb shelters devoid of electricity (Sharifian et al., 2021). Understanding the educational landscape during crises like war is critical for developing effective strategies to mitigate the negative impacts on students, teachers, and the overall education infrastructure. Research in this area can shed light on various aspects, including access to education, quality of learning, mental health implications, displacement of students and teachers, destruction of educational facilities, and the role of education in fostering resilience and recovery.

Our study, using the case of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war which started on February 2022 and is the largest military conflict since WWII (Kurapov et al., 2023; Mankoff, 2022; Nikolaev et al., 2023), explores how the Ukrainian teachers and students experience educational process. The military conflict which started directly after the pandemic pushed the Ukrainian students and staff into a lengthy period of enforced online education. Most institutions implemented blended/distance learning to ensure participants’ safety (Semerikov et al, 2023). At this moment, the Ukrainian HEIs continue to strive, and the educational process is taking place in an atypical long-term crisis. Thus, the revelatory case of Ukrainian HEIs with their undoubtedly unique experiences offers opportunities for analysis of the dynamics of development, experiences of students and staff, and the enduring repercussions of profound crises like war on higher education (HE).

Our research employs an anonymous online survey distributed to both teachers and students enrolled at a public Higher Education Institution (HEI) located in the Kharkiv region. This region stands out as one of the areas most severely affected by shelling since the onset of the full-scale invasion. The primary objective of our study is to delve into the respondents’ evaluations of the educational process amidst such challenging circumstances. We aim to identify the problems they encountered and their preferences regarding educational formats. Furthermore, our study delves into the perceptions and experiences surrounding the digitalization of the educational process. We seek to understand how both teachers and students perceive the integration of digital tools and platforms into their learning and teaching experiences. Additionally, we explore the emotional state of the participants in response to the crisis situation and its impact on their educational journey. Finally, our research scrutinizes the assessment of digital skills by both teachers and students. We aim to gauge the level of proficiency and comfort with digital technologies among educators and learners alike, considering the increased reliance on online learning modalities in the face of physical disruptions caused by the crisis.

The subsequent sections of the paper unfold as follows. Firstly, a literature review is presented in the section “Previous research”, offering an in-depth exploration of existing research about crises in educational contexts. This review sets the stage for understanding the broader empirical evidence and key concepts relevant to the study’s focus. Following the literature review, an overview of the methods employed in the research is provided. This section delineates the research design, including details about the survey, sampling procedure, data collection process and participants, data analysis and ethical considerations. Subsequently, the paper proceeds to present the findings derived from the study. The Discussion section follows, where the findings are critically examined and interpreted in light of the extant literature on crises in educational contexts. This section offers a nuanced analysis of the implications of the study’s findings, highlighting their significance, relevance, and potential contributions to the broader research field. Finally, the paper concludes with a section dedicated to summarizing the key findings, discussing their implications, and offering reflections on the study’s limitations. Additionally, suggestions for future research directions are proposed, outlining potential avenues for further inquiry and exploration in this area of study.

Previous Research

Kreps (1984) defines crisis as “events, observable in time and space, in which societies or their larger subunits (e.g., communities, regions) incur physical damages and losses and/or disruption of their routine functioning” (p.312). Pauchant and Mitroff (1988) also emphasize the impact of the crisis on people, crisis “disturb[ing] people’s subjective world: the way they perceive the world and themselves; their inner sense of self-worth, power, and identity; their inner cohesion” (p.8). Crisis can act as a catalyst for innovation initiatives, pushing organizations to search for solutions to adapt to sudden changes, meet new demands, or address unforeseen challenges (Boh et al., 2023; Buck et al., 2022; Lubna Alam et al., 2022).

For Ukraine, the extensive crisis caused by the pandemic resulted in a tremendous digital transformation of HE (Ionan, 2022). Before the pandemic, most of the HEIs used only certain elements of online education and relied on the Moodle system, which was used sporadically, for certain circumstances, e.g., online courses for convicts in colonies (Stukalo & Simakhova, 2020). The pandemic paved the way for the adoption of new technologies in the Ukrainian HEIs in terms of development and launching of new educational platforms (Gareeva & Chursanova, 2021; Polianovskyi et al., 2021) and pushing forward the development of teachers’ professional digital competence (Makhachashvili & Semenist, 2021). Similar to many other countries, switching to online education amidst a crisis came with certain challenges, such as technological challenges originating from lack of proper technologies (Matvijchuk et al., 2021), emotional and psychological problems experienced by teachers and staff due to isolation (Prokopenko & Berezhna, 2020), insufficient methodological recommendations for conducting distance education for various types of learning courses and training activities (Klochko et al., 2021), lack of access to libraries and digital textbooks (Molchanova et al., 2020) and limited funding for purchasing full versions of software (Nenko et al., 2020), to mention a few.

Limited research is available on how education is conducted in other types of crises than the pandemic. In armed conflicts, such as Israeli-Gaza war, continuous online student-teacher contact using social media channels contributes to resilience and is pivotal for emotional support (Rosenberg et al., 2018). As a response to a series of major earthquakes in the Canterbury region of New Zealand in 2010 and 2011, online blended learning was introduced in a short period to ensure continuity of education, despite limited access to digital tools and poor digital skills of teaching staff and students (Mackey et al., 2012). The hurdles experienced by academic staff in Hurricane Katrina, presented by (McLennan, 2006), show the importance for online instructors to prepare an agreement with courseware providers for interruption of service during emergencies, ensuring alternative platform capabilities in case of disruptions. Furthermore, making digital copies of teaching materials to recreate their e-learning course sites and evacuating them, if necessary, in case of possible damage, was mentioned.

Few studies have explored digital transformation and the experiences of teachers and students in the Ukrainian HE (Bondar et al., 2023). The research conducted by the State Education Quality Service of Ukraine (2023) shows that the key challenges for educators in the war are primarily unstable learning conditions, limited ways to organize learning activities, reduced motivation, and unstable psycho-emotional state of participants in the educational process as well as human capital loss. The study shows that addressing the problem of human capital loss is one of the main challenges. The only measures envisaged are the regulation of admission from the temporarily occupied territories and territories of active hostilities, a communication campaign to return participants to the educational process after the end of hostilities, provision of psychological support, and legislative regulation of the resumption of educational institutions after de-occupation. At the same time, it should be noted that due to the inertia of the educational system and the lack of flexible approaches to management in educational institutions, in almost half of the cases, class schedules, curricula, requirements for students, and teacher workflow have not significantly changed (State Education Quality Service of Ukraine, 2023). Recent studies of the impact of the digitalization of the educational process on its participants show that there are significant signs that teachers and students are experiencing a certain level of overload with online activities, which leads to the need to research and find ways to relieve the participants of the educational process or switch them to different modes of activity, including off-screen, in the face of a long-term crisis, without losing learning outcomes (Berbyuk Lindström et al., 2024).

Possible options for reducing the negative impacts of the crisis on the HE system of Ukraine are still unclear. This is where this study aims to contribute by exploring the perceptions of students and staff on education in times of war to provide insights into the challenges as well as opportunities for improving educational practices, fostering resilience, and promoting peace-building initiatives amidst adversity.

Methodology

Setting and Participants

The study was carried out between June and August 2023, immediately following the conclusion of the first full academic year amidst the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Employing a random sampling method, the survey was disseminated to both academic staff and students of a single HEI located in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Notably, this sampling approach ensured that participants were selected without regard to gender, length of service, academic degree, or academic rank. To preserve participant anonymity and encourage candid responses, data regarding students’ and staff’s affiliations with specific faculties, departments, or specialties were intentionally omitted from the survey. This decision aimed to foster an environment of openness and honesty among respondents.

The survey instrument was designed and administered using Google Forms, a user-friendly online platform for data collection. Distribution of the survey was facilitated by the deans of the respective faculties, who played a crucial role in reaching out to and engaging with the participants.

In total, 450 students and 55 academic staff members answered the survey which contained the following parts:

- identification of problematic issues, bottlenecks, and stress factors of participants in the organization of the educational process;

- determination of the university’s capabilities in organizing and coordinating the digital learning process, in terms of assessing the technical capabilities;

- determining the sense of comfort and safety of participants in the digital educational environment by rating the convenience and arrangement of the workplace;

- comparison of the perceptions of participants of the educational process, e. academic staff and students, concerning the quality of higher education in crisis.

Data Analysis and Ethical Considerations

The data collection and tabulation process were conducted through a Google Form within the initial two weeks of the study period. The methodological approach based on descriptive statistics was employed to analyze the challenges encountered by respondents in navigating the digital educational process amidst an enduring crisis. This analytical method facilitated a comprehensive examination of the issues faced by participants and their perspectives on potential strategies for enhancing the quality of education in such circumstances. Furthermore, factor analysis was utilized to explore the underlying structure of the scale measuring subjective and objective assessments of digital skills and capabilities among participants involved in the educational process during a prolonged crisis. This analytical technique allowed for the identification of distinct factors or dimensions within the data, shedding light on the multifaceted nature of digital proficiency and its implications for educational practice. Moreover, factor analysis was also applied to investigate respondents’ attitudes toward the role of teachers and the university as a whole in the realm of digital learning within the context of an enduring crisis. By scrutinizing the interrelationships between various survey items, factor analysis facilitated a deeper understanding of participants’ perceptions and expectations regarding the integration of digital technologies into the educational landscape during times of prolonged crisis. Overall, the utilization of descriptive statistics and factor analysis in this study enabled a systematic examination of the challenges, perceptions, and capabilities related to digital education in times of crisis.

The research protocol was approved by the Educational and Methodological Department of the Simon Kuznets Kharkiv National University of Economics, Kharkiv, Ukraine.

Results

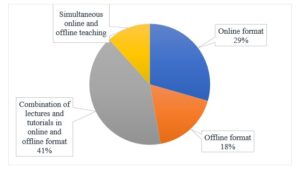

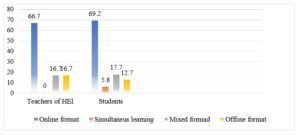

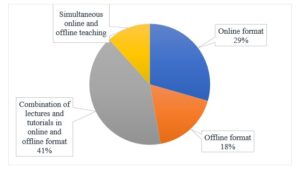

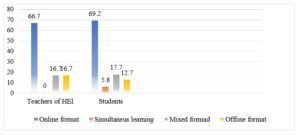

To start with the preferred forms of education, the opinions and attitudes of staff and students are presented in Figure1 and 2 below:

Fig. 1 Distribution of respondents’ opinions on the most effective form of education in the long term

Fig. 2 Comparative analysis of the opinions of respondents (teachers and students) on the format of the educational process in the next semester of the 2023-2024 academic year

Source: conducted by the authors

Figure 1 illustrates a noteworthy trend wherein a significant majority of both students and teachers express a preference for a blended approach to education, encompassing both online and offline components. Specifically, 41% of the respondents indicate that a combined online and offline format, characterized by online teaching complemented by in-person activities, is deemed the most effective form of education in the long term, followed by the online format (29%). Conversely, the least favored options include the simultaneous online and offline format, commonly referred to as a hybrid model, where some participants engage online while others attend in person, garnering only 12% of preferences. Similarly, the offline format, devoid of online elements, emerges as the least preferred choice, with only 18% of respondents expressing a preference for this mode of education. Overall, the data from Figure 1 underscore a clear inclination towards a blended educational approach, highlighting the perceived value of integrating both online and offline modalities to optimize the learning experience in the long run.

Figure 2 shows a notable contrast that emerges between the preferences of students and teachers regarding physical attendance at educational institutions amidst the dangers posed by shelling and unpredictability. A mere 12.7% of students and 16.7% of teachers express a willingness to attend in person despite the associated risks to life and the uncertain circumstances surrounding shelling incidents. Moreover, concerning hybrid education, where classes are conducted simultaneously for both physically present students and those participating online. While no teachers express a preference for this mode of instruction, 5.8% of the students indicate a willingness to engage in the educational process in this manner.

These findings underscore divergent perspectives between students and teachers regarding the feasibility and desirability of physical attendance at educational institutions amidst precarious conditions. Additionally, the lack of enthusiasm among teachers for hybrid education suggests potential challenges in implementing this instructional format, further highlighting the complexity of navigating educational delivery during times of crisis.

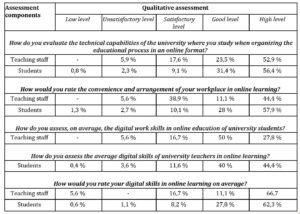

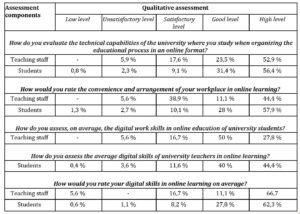

Turning to the conditions for the educational process in terms of digital infrastructure and skills, the findings are presented in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Сomparative assessments of the participants’ capabilities during the digital educational process in the academic year 2022-2023

Source: conducted by the authors

An interesting finding from the study is that a substantial portion of respondents perceive their HEI to possess commendable technical capabilities, particularly in terms of communication platforms and the quality of digital learning content. Specifically, over half of the respondents, comprising 56.4% of students and 52.9% of teachers, regard these technical provisions as either “high” or “good”. This indicates a promising trajectory for the university in its journey towards digital transformation, suggesting that efforts in enhancing technological infrastructure and digital learning resources have yielded positive outcomes. However, there exists a notable difference between the satisfaction levels of teachers and students regarding the comfort of their remote work environment. While a majority of students (57.9%) rate the comfort of their remote workplace as very high, only 44.4% of teachers share the same opinion. Further, a smaller proportion of teachers, compared to students, perceive the comfort level as good (11.2% of teachers and 28% of students). This incongruity underscores the importance of further investigation into the factors influencing the comfort and effectiveness of remote work arrangements for educators.

Furthermore, the study highlights differing perspectives on digital skills’ assessment between teachers and students. Teachers tend to be more critical of students’ digital skills, with only 27.8% rating them as high, whereas a significantly larger percentage of students, at 44.4%, perceive teachers’ digital skills at a high level. Interestingly, a majority of both teachers and students rate their own digital skills highly (66.7% of teachers and 62.3% of students), indicating a self-perceived proficiency in this domain. This finding underscores the need for targeted interventions aimed at bridging the gap between teachers’ expectations and students’ perceptions regarding digital competencies, while also acknowledging the importance of fostering a culture of continuous digital skill development within the educational community.

The analysis of open-ended responses to the question regarding the primary challenges encountered by participants in the educational process reveals distinct concerns raised by both staff and students. Staff members highlighted several issues, including difficulties in obtaining feedback from students, excessive working hours that surpass established norms, challenges in crafting educational content conducive to independent learning, and access to necessary technology such as high-quality microphones and licensed software. Moreover, interruptions caused by shelling and power outages, particularly for those residing in Ukraine, were cited as significant impediments. On the other hand, students expressed their main difficulties, which primarily revolved around power outages and connectivity issues, including problems accessing the university network. Furthermore, the absence of face-to-face interaction with peers and instructors, along with feelings of academic overload, emerged as prominent concerns. Some respondents also lamented the perceived lack of engaging and relevant educational materials provided by instructors, citing limited updates to course content, an escalation in independent study requirements, and inadequate technical equipment such as cameras and microphones.

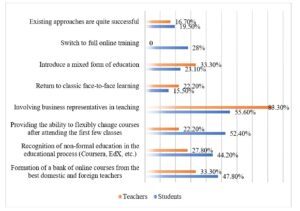

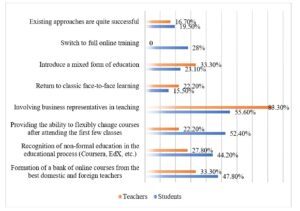

Figure 3 presents the findings on the attitudes of participants in the educational process toward the role of the university, the qualities that a teacher should have, and the main areas for improvement of the quality of higher education.

Fig.3 Comparative analysis of respondents’ opinions on approaches that, in their opinion, will improve the quality of higher education

Source: conducted by the authors

The findings presented in Figure 3 indicate dissatisfaction among respondents regarding current educational approaches, with less than 19.5% of students and 16.7% of staff expressing satisfaction with the status quo. Moreover, there is a general skepticism toward online education, particularly among teachers. Only about 28% of students advocate for HE institutions transitioning entirely to online education, while no teachers support this notion. Interestingly, teachers exhibit a more positive stance towards the implementation of a mixed education model, with 33.3% expressing support, compared to 23.1% of students. Similarly, teachers are more inclined towards returning to face-to-face education, with 22.2% in favor, compared to 15.5% of students. The teachers also demonstrate a greater openness to the involvement of business representatives in educational activities, with 83.3% expressing support, as opposed to 55.6% of students. Conversely, students express a preference for increased flexibility in education, such as the ability to change courses (52.4% of students compared to 22.2% of teachers) and the recognition of non-formal education (44.2% of students and 27.8% of teachers). Additionally, students exhibit a stronger inclination towards the establishment of a bank of online courses featuring the expertise of both domestic and foreign educators, with 47.8% expressing support, compared to 33.3% of teachers.

Discussion

The Ukrainian HEIs face a long-term crisis caused first by the pandemic and then the war. This study delves into the experiences of teachers and students within Ukrainian higher education institutions (HEIs) during times of war, shedding light on the challenges and opportunities arising from the crisis for education.

Our research findings reveal that the majority of both students and staff assess the technical capabilities of their HEI as high and express satisfaction with communication platforms, as well as the completeness and quality of digital learning content. Moreover, respondents indicate satisfaction with their own digital skills as well as those of their peers. Interestingly, the acceleration of digital transformation precipitated by the preceding pandemic crisis has had a significant impact on managing the subsequent war crisis. Consistent with prior studies (Berbyuk Lindström et al., 2023; Bondar et al., 2023; Sofkova Hashemi et al., 2023), our research underscores the role of digital transformation, initiated during the previous crisis, i.e. the COVID-19 pandemic, in equipping students and teachers with the necessary skills to navigate educational technologies. This proficiency has facilitated the continuation of work and study activities amidst the ongoing conflict. Of particular note is the preference for a combined form of education, blending digital and on-site components. Despite the challenges posed by shelling, which restrict opportunities for physical gatherings and pose risks to participants’ safety, respondents acknowledge and value the importance of in-person interactions. One plausible explanation for this preference may be the fatigue stemming from an extended period of online education, initiated during the pandemic. Our finding is in line with earlier findings on declining well-being over lengthy periods of working remotely, especially in extremely stressful environments (Golden and Veiga, 2005). This finding underscores the potential limitations of sustained online education and emphasizes the need for HEIs to consider alternative approaches. Incorporating on-site meetings into the educational model could help mitigate the challenges associated with prolonged online learning periods, ensuring a more balanced and effective learning experience and well-being for students and staff.

The findings show that students are somewhat happier with their remote working environment than the teachers. The feedback from staff underscores a prevalent issue: many teachers find themselves working far beyond the established norms, resulting in heightened stress levels and eventual burnout. Additionally, several respondents have voiced concerns about the scarcity of engaging and current educational materials, coupled with a notable rise in the demand for independent study. These observations suggest potential fatigue among educators and diminished enthusiasm for crafting new content and adopting new technologies (Choi et al., 2014), likely stemming from the prolonged duration of remote work and the added strain induced by the ongoing conflict (Hodges et al., 2020).

For the teachers, technical challenges in terms of limited access to quality technical means (camera, microphone, etc.) and full versions of software additionally complicate providing quality teaching. The students mainly mention power outages and problems with connecting to the network, including the university network, as well as a lack of personal communication with other students and teachers. These findings are similar to the experiences from the early stages of the pandemic when academic staff and students struggled with overwork, loneliness, and lack of access to technology (Mäkelä et al. 2022, Hietanen and Svedholm-Häkkinen 2023). At the same time, the pandemic did not cause power outages, which is the factor that additionally complicates remote work and education in war. Further, research shows that during the pandemic there was interest from teachers and students in exploring new technologies and testing new teaching methods (Carugati et al., 2020). In our study, these tendencies are not visible, which might indicate that multiple crises and psychological stress impede innovation. This finding emphasizes the necessity for further research to delve into how the spirit of innovation can be sustained during prolonged periods of crisis. Exploring methods to support and nurture innovation among educators amidst adversity is crucial for maintaining the quality and relevance of educational content. Understanding how to foster creativity and adaptability in such challenging circumstances can not only alleviate burnout among teachers but also enhance the resilience of organizations (Duchek, 2020).

Finally, our findings reveal a significant level of criticism among respondents towards current educational approaches, particularly with regard to online education not being perceived as the preferred mode of operation in HE institutions. This sentiment raises concerns regarding the long-term viability of prolonged online education mandates, potentially compromising the quality of teaching and learning experiences. Notably, these concerns are primarily voiced by teachers, who express a strong inclination towards returning to traditional face-to-face education settings. In contrast, students exhibit a preference for flexibility, embracing changes in course structures, and valuing non-formal education opportunities. This disparity in perspectives highlights a tension between the desires of students and staff regarding the adaptability and flexibility of HE institutions to meet evolving educational needs. These tensions must be carefully considered in discussions surrounding the restructuring of HE in Ukraine post-war, emphasizing the importance of accommodating diverse preferences while ensuring the quality and effectiveness of education delivery.

Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

The study contributes to the research on the impact of crisis on the educational context. Our study underscores the considerable challenges inherent in delivering education amidst prolonged crises, particularly highlighting the burdens faced by teachers and students. The study indicates that it is imperative to allocate special attention not only to the logistics of organizing education during emergencies but also to addressing the critical issue of providing participants in the educational process with the necessary technical resources for teaching and learning. Furthermore, solutions aimed at offering psychological support for both students and teachers are paramount for maintaining the quality of education amidst extended periods of enforced remote work and learning. These measures are essential for safeguarding the well-being and effectiveness of the educational community during times of prolonged crisis.

Turning to limitations, the sample size was confined to one educational institution in Ukraine, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to the national level. The experiences of the students and staff from the Ukrainian HEIs less affected by military operations might differ in terms of opportunities of on-site education. However, these findings do offer valuable insights and serve as a foundation for further research in related areas. Despite this limitation, the study provides the initial groundwork for comprehensively understanding the experiences of higher education participants amidst extreme conditions. Additionally, the study establishes baseline data that can be utilized for comparison in future research endeavors.

Considering data collection, the dataset exclusively comprised survey data, which may constrain the depth of interpretation regarding the delivery of digital education during emergencies to subjective reports of experience. While these data provide valuable insights into the experiences, challenges, and perceptions of faculty and students regarding teaching methods and digital technologies, future research should aim to gather a more diverse array of data, including interviews, observations and policy documents. A triangulated perspective on the phenomenon of experiences of education in times of crisis can lead to a more nuanced understanding of how HEIs can effectively address the challenges of online learning and cater to students’ needs

References

- Appolloni, A., Colasanti, N., Fantauzzi, C., Fiorani, G., & Frondizi, R. (2021). Distance Learning as a Resilience Strategy During Covid-19: An Analysis of the Italian Context. Sustainability, 13(3), 1388.

- Bellini, M. I., Pengel, L., Potena, L., Segantini, L., & Group, E. C. W. (2021). Covid‐19 and Education: Restructuring after the Pandemic. Transplant International, 34(2), 220-223.

- Berbyuk Lindström, N; Sofkova Hashemi, S; and Bergdahl, N, “ONLINE EDUCATION FOR ALL? IMPACT OF COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON TEACHERS’ PROFESSIONAL DIGITAL COMPETENCE DEVELOPMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF MUNICIPAL ADULT EDUCATION FOR MIGRANTS” (2023). ECIS 2023 Research Papers. 294.

https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2023_rp/294

- Berbyuk Lindström, N., Asatiani, A., Kononova, N. (2024). Exploitation and Exploration of Digital Technologies in Times of War: Experiences of Ukrainian Higher Education Institutions. ECIS proceedings, forthcoming.

- Boh, W., Constantinides, P., Padmanabhan, B., & Viswanathan, S. (2023). Building Digital Resilience against Major Shocks. MIS Quarterly, 47(1), 343-360.

- Bondar, K., Shestopalova, O., Hamaniuk, V., & Tursky, V. (2023, March). Ukraine higher education based on data-driven decision making (DDDM). In CTE Workshop Proceedings (Vol. 10, pp. 346-365).

- Buck, C., Kreuzer, T., Oberländer, A. M., Röglinger, M., & Rosemann, M. (2022). Four Patterns of Digital Innovation in Times of Crisis. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 50(1), 35.

- Carugati, A., Mola, L., Plé, L., Lauwers, M., & Giangreco, A. (2020). Exploitation and exploration of IT in times of pandemic: from dealing with emergency to institutionalising crisis practices. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(6), 762-777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1832868

- Chang-Bacon, C. K. (2021). Generation Interrupted: Rethinking “Students with Interrupted Formal Education”(Sife) in the Wake of a Pandemic. Educational Researcher, 50(4), 187-196.

- Choi, H.-H., Van Merriënboer, J. J. and Paas, F. (2014) ‘Effects of the physical environment on cognitive load and learning: Towards a new model of cognitive load’, Educational psychology review, 26, 225-244.

- Cone, L., Brøgger, K., Berghmans, M., Decuypere, M., Förschler, A., Grimaldi, E., Hartong, S., Hillman, T., Ideland, M., and Landri, P. 2022. “Pandemic Acceleration: COVID-19 and the Emergency Digitalization of European Education,” European Educational Research Journal (21:5), pp. 845-868.

- Cuny, F. C. (1994). Disasters and Development. Intertect Press.

- Duchek, S. (2020) ‘Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization’, Business Research, 13(1), 215-246.

- Fenwick, M., McCahery, J. A., & Vermeulen, E. P. (2021). Will the World Ever Be the Same after Covid-19? Two Lessons from the First Global Crisis of a Digital Age. European Business Organization Law Review, 22, 125-145.

- Gareeva, F. M., & Chursanova, M. V. (2021). Organization of the educational process at the National Technical University of Ukraine «Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute» during COVID-19 quarantine.

- Golden, T. D., & Veiga, J. F. (2005). The Impact of Extent of Telecommuting on Job Satisfaction: Resolving Inconsistent Findings. Journal of Management, 31(2), 301-318.

- Hietanen, M., and Svedholm-Häkkinen, A. M. 2023. “Transition to Distance Education in 2020–Challenges among University Faculty in Sweden,” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research (67:3), pp. 433-446.

- Hodges C, Moore S, Lockee B et al. (2020) The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review, 27 March 2020. Available at: https:// er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teachingand-online-learning (accessed 10 July 2023).

- Hofer, S. I., Nistor, N., & Scheibenzuber, C. (2021). Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Lessons Learned in Crisis Situations. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106789.

- Ionan, V. (2022). Digital Transformation in Ukraine: Before, During, and after the War. ALI Social Impact Review. URL: https://www. sir. advancedleadership. harvard. edu/articles/digital-transformation-in-ukraine-before-duringafterwar.

- Klochko, V., Kulynych, T., Chuiko, N., Postolna, N., & Holovanova, O. (2021). Comparison of distance education problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. ScienceRise(2), 59-64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21303/2313-8416.2021.001776

- Kreso, A.P. (2008). The War and Post-War Impact on the Educational System of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In: Majhanovich, S., Fox, C., Kreso, A.P. (eds) Living Together. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9816-1_5.

- Kurapov, A., Pavlenko, V., Drozdov, A., Bezliudna, V., Reznik, A., & Isralowitz, R. (2023). Toward an Understanding of the Russian-Ukrainian War Impact on University Students and Personnel. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 28(2), 167-174.

- LeBlanc, P. (2020). COVID-19 Has Thrust Universities into Online Learning—How Should They Adapt? ,The Brookings Institution, Washington.

- Lin, R., Yang, J., Jiang, F. et al. (2023) Does teacher’s data literacy and digital teaching competence influence empowering students in the classroom? Evidence from China. Educ Inf Technol 28, 2845–2867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11274-3

- Lubna Alam, S., Mirkovski, K., Scheepers, R., & Saundage, D. (2022). Setting Priorities for Exploiting and Exploring Digital Capabilities in a Crisis. MIS Quarterly Executive, 21(4), 6.

- Mackey, J., Gilmore, F., Dabner, N., Breeze, D., & Buckley, P. (2012). Blended Learning for Academic Resilience in Times of Disaster or Crisis. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 8(2).

- Makhachashvili, R., & Semenist, I. (2021). e-Skills and Digital Literacy for Foreign Languages Education: Student Case Study in Ukraine International Association for Development of the Information Society, 15th International Conference e-Learning, EL 2021 – Held at the 15th Multi-Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, MCCSIS 2021 3-14, 2021.

- Mankoff, J. (2022). Russia’s War in Ukraine: Identity, History, and Conflict. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

- Matvijchuk, О., Jerementko, R., & Matvijchuk, А. (2021). Distance education at the National Pharmaceutical University during the COVID-19 pandemic. Challenges and prospects.

- Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, 2021. Digital transformation of education and science is one of the key goals of the Ministry of Education and Science for 2021, – Sergiy Shkarlet. Available at: http://mon.gov.ua/

- McLennan, K. L. (2006). Selected Distance Education Disaster Planning Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 9(4), n4.

- Molchanova, E., Kovtoniuk, K., & Savych, O. (2020). Covid-19 Presents New Challenges and Opportunities to Higher Education Revista Romaneasca pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(2), 168-174.

- Mäkelä, T., Sikström, P., Jääskelä, P., Korkala, S., Kotkajuuri, J., Kaski, S., and Taalas, P. 2022. “Factors Constraining Teachers’ Wellbeing and Agency in a Finnish University: Lessons from the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Education Sciences (12:10), p. 722.

- Müller LM and Goldenberg G (2020b) Education in times of crisis: Teachers’ views on distance learning and school reopening plans during COVID-19: Analysis of responses from an online survey and focus groups. Chartered College of Teaching. Available at: https://my.chartered.college/resources/publications/ (accessed on 11 July 2023)

- Nenko, Y., Кybalna, N., & Snisarenko, Y. The COVID-19 Distance Learning: Insight from Ukrainian students. Revista Brasileira de Educação do Campo The Brazilian Scientific Journal of Rural Education, 20.

- Nikolaev, E., Rij, Г., & Shemelynets, I. (2023). Higher Education in Ukraine: Changes Due to War (Analytic center Kyiv University named after Boris Grinchenko, Issue.

- Rosenberg, H., Ophir, Y., & Asterhan, C. S. C. (2018). A Virtual Safe Zone: Teachers Supporting Teenage Student Resilience through Social Media in Times of War. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 35-42.

- OECD (2020). A framework to guide an education response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020. – Available at: https://globaled.gse.harvard.edu/files/geii/files/framework_guide_v2.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2023)

- Pashkov, Viktor. (2021). THE CRISIS IN THE HIGHER EDUCATION SYSTEM OF CONTEMPORARY UKRAINE IN THE CONTEXT OF NATIONAL SECURITY CHALLENGES. Strategic Panorama. 80-93. https://doi.org/10.53679/2616-9460.1-2.2021.06

- Pauchant, T. C., & Mitroff, I. I. (1988). Crisis Prone Versus Crisis Avoiding Organizations Is your company’s culture its own worst enemy in creating crises? Industrial Crisis Quarterly, 2(1), 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/108602668800200105

- Peters, M. A., Rizvi, F., McCulloch, G., Gibbs, P., Gorur, R., Hong, M., Hwang, Y., Zipin, L., Brennan, M., Robertson, S., Quay, J., Malbon, J., Taglietti, D., Barnett, R., Chengbing, W., McLaren, P., Apple, R., Papastephanou, M., Burbules, N., Jackson, L., Jalote, P., Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Fataar, A., Conroy, J., Misiaszek, G., Biesta, G., Jandrić, P., Choo, S. S., Apple, M., Stone, L., Tierney, R., Tesar, M., Besley, T., and Misiaszek, L. 2022. “Reimagining the New Pedagogical Possibilities for Universities Post-COVID-19,” Educational Philosophy and Theory (54:6), pp. 717-760.

- Polianovskyi, H., Zatonatska, T., Dluhopolskyi, O., & Liutyi, I. (2021). Digital and Technological Support of Distance Learning at Universities under COVID-19 (Case of Ukraine). Revista Romaneasca pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 13(4), 595-613.

- Prokopenko, I., & Berezhna, S. (2020). Higher Education Institutions in Ukraine during the Coronavirus, or COVID-19, Outbreak: New Challenges vs New Opportunities. Revista Romaneasca pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(1), 130-135.

- Rosenberg, H., Ophir, Y., & Asterhan, C. S. C. (2018). A Virtual Safe Zone: Teachers Supporting Teenage Student Resilience through Social Media in Times of War. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 35-42.

- Semerikov, S.O., Vakaliuk, T.A., Mintii, I.S. and Didkivska, S.O., 2023. Challenges facing distance learning during martial law: results of a survey of Ukrainian students. Educational Technology Quarterly [Online], 2023(4), pp.401–421. Available from: https://doi.org/10.55056/etq.637

- Sharifian, M. S., Dornblaser, L., & Silva, S. Y. V. (2021). Education During the Active War: Exploring Teachers’ Perceptions and Practice in Syria. Journal of Education in Muslim Societies, 3(1), 50-67.

- Sofkova Hashemi, Sylvana; Berbyuk Lindström, Nataliya; Brooks, Eva Irene; Háhn, Judit; and Sjöberg, Jeanette, “Impact of Emergency Online Teaching on Teachers’ Professional Digital Competence: Experiences from the Nordic Higher Education Institutions” (2023). ICIS 2023 Proceedings. 12.

https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2023/learnandiscurricula/learnandiscurricula/12

- State Education Quality Service of Ukraine, 2023. Available at: https:// sqe.gov.ua/tretina-uchniv-v-umovakh-viyni-ne-mali-po/ (accessed on 9 July 2023)

- Stukalo, N., & Simakhova, A. (2020). COVID-19 impact on Ukrainian higher education. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(8), 3673-3678. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.080846