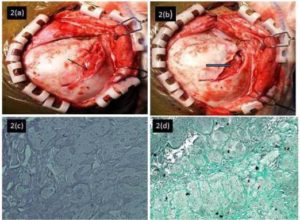

Since clinically and histopathologically the herniated tissue was the cerebrum in our case, it was classified as Type II growing skull fracture (Naim Ur Rahman et al, 1994). Morphologically, the predominant factor responsible for fracture growth may lie in the subarachnoid space (a leptomeningeal cyst), the cerebrum (herniated brain), or the ventricle (dilated underlying ventricle with porencephalic cyst). These events constitute the morphological basis for the fracture types I, II, and III, respectively (Naim Ur Rahman et al, 1994).

Discussion

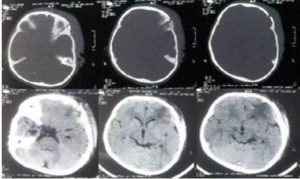

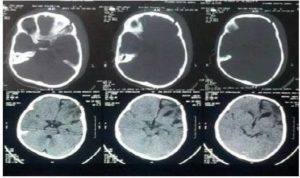

Growing skull fracture has been described in the literature as an entity synonymous to aleptomeningeal cyst due to collection of CSF underneath. The other names of it include enlarging skull fracture, expanding skull fracture, post-traumatic bone absorption, post-traumatic porencephaly, traumatic ventricular cyst, craniocerebral erosion, and cephalohydrocele (Suri A, Mahapatra AK, 2002). It was first recognized and reported by John Howship in 1876 (Gupta S K 1997).They mostly arise in cranial convexity, but cases occurring in orbital roof (Mohindra S 2006) and posterior fossa (Gupta S K 1997) have also been reported. Although the majority of patients present with complaints 2 to 12 months after the traumatic event, delay in presentation for 8 to 20 years has also been reported. Suri et al have reported that orbital floor fractures occur primarily in older children with mean age 12.0 ± 4.2 years due to increased vulnerability of the face due to growth and pneumatization of the maxillary sinus (Suri A, Mohapatra AK, 2002). Meier et al. have reported leptomeningeal cyst of orbital roof in a 47-year-old female who had a remote history of skull fracture at the age of 3 years (Meier JD, Dublin AB, Strong EB, 2009). Halliday AL, Chapman PH, Heros RC, (1990) and Naim-Ur-Rahman (1994) reported a case of a growing skull fracture following injury in adult life. The most common causes of head injury in children are as follows: falls, child abuse, motor vehicle accidents, sport accidents, assaults, and instrumental delivery (Ciurea AV, 2011). Predisposing factors include linear skull fracture, disruption of the underlying duramater, and raised intracranial pressure due to cerebral oedema, contusion, or in occasions even a normally growing brain (Mohindra S, 2006). Malleability of the infant skull and rapid growth of brain and skull leading to tighter adherence of dura to bone in children may account for the common occurrence of growing fractures in children (Rahimizadeh A, 1986). This complication is caused by a tear in the duramater, through which pulsation of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) forces the arachnoid layer with or without brain parenchyma to herniate. This causes bone malnutrition, destroying the bone edge, and finally enlarges the fracture line. Associated lesions like hydrocephalus, encephalomalacia, cerebralinfarct, leptomeningeal cyst, brain tissue herniation, subdural fluid collection, and ipsilateral ventricular dilatation were previously reported preoperatively (Ali Akhaddar A, 2011).Post-traumatic aneurysms and subdural hematomas have also been reported to accompany growing skull fractures (Buckinghum MJ, 1989 and Locatekku D,1989) although damage to underlying brain is not a prerequisite for the development of growing skull fractures (Iyer S G, 2003). They can also mimic a skull tumour (Kurosu A, 2004) especially if seen in adults presenting as bone cyst, where histopathology is essential to rule out the tumour.

Prompt diagnosis is essential as early corrective surgery should be performed for growing skull fractures so as to prevent secondary brain damage and neurological deficits which especially occur in late stages and lead to progressive disruption in the quality of life of patients (Liu X, 2012). A clinical, radiological, and histopathological correlation helps in diagnosing types of growing skull fracture and thereby to assess its prognosis. Surgical treatment involving excision of meningocele and repair of bone and dural defects is associated with good outcome. Dural defect needs to be fully repaired. Although, in infants and children, linear skull fractures should be monitored until definite skull bone consolidation so as to prevent progression, they should not be left neglected.

References

Ali Akhaddar, A., Mercier, P., Diabira, S., Fournier, D. & Menei, P. (2011). “Growing Skull Fracture Combined with Schizencephaly,” Pan Arab journal of neurosurgery, 15(2), 87-9

Publisher – Google Scholar

Buckingham, Martin J. M. D., Crone, Kerry R. M. D., Ball, William S. M. D., Tomsick, Thomas A. M. D., Berger, Thomas S. M. D., Tew, John M. Jr. M. D. (1988). “Traumatic Intracranial Aneurysms in Childhood: Two Cases and Review of Literature,” Neurosurgery, 22(2), 398-408.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ciurea, A. V., Gorgan, M. R., Tascu, A., Sandu, A. M. & Rizea, R. E. (2011). “Traumatic Brain Injury in Infants and Toddlers, 0—3 Years Old,” J Med Life, 4(3), 234—43.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Gupta, S. K., Reddy, N. M., Khosla, V. K., Mathuriya, S. N., Shama, B. S., Pathak, A., Tewari, M. K. & Kak, V. K. (1997). “Growing Skull Fractures: A Clinical Study of 41 Patients,” Acta Neurochir (Wein), 139(10),928-32.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Halliday, A. L., Chapman, P. H. & Heros, R. C. (1990). “Leptomeningeal Cyst Resulting from Adulthood Trauma: Case Report,” Neurosurgery, 26(1), 150-3.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Iyer, S. G., Saxena, P. & Kumhar, G. D. (2003). “Growing Skull Fractures,” Indian Pediatrics, 40(2), 1194-6

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kurosu, A., Fujii, T. & Ono, G. (2004). “Post-Traumatic Leptomeningeal Cyst Mimicking a Skull Tumour in an Adult,” Br J Neurosurg, 18(1), 62-4.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kutlay, M., Demircan, N., Akin, O. N. & Basekim, C. (1998). “Untreated Growing Cranial Fractures Detected in Late Stage,” Neurosurgery, 43(1), 72—6.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Liu, X., You, C., Lu, M. & Liu, J. (2012). “Growing Skull Fracture Stages and Treatment Strategy,” Journal of Neurosurgery, Pediatrics, 9(6), 670—5.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Locatekku, D., Messina, A. L., Bonfanti, N., Pezzotta, S. & Gajno, T. M. (1989). “Growing Fractures: An Unusual Complication of Head Injuries in Pediatric Patients,” Neurochirurgia (stuttg), 32(4), 101-4.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Meier, J. D., Dublin, A. B. & Strong, E. B. (2009). “Leptomeningeal Cyst of the Orbital Roof in an Adult: Case Report and Literature Review,” Skull Base, 19(3), 231-5.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Mohindra, S., Mukherjee, K. K., Chhabra, R. & Gupta, R. (2006). “Orbital Roof Growing Fractures: A Report of Four Cases and Literature Review,” Br J Neurosurg, 20(6), 420-3.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Naim-Ur-Rahman, Jamjoom, Z., Jamjoom, A. & Murshid, W. R. (1994). “Growing Skull Fractures: Classification and Management,” Br J Neurosurg, 8(6), 667-79.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rahimizadeh, A. & Haddadian, K. (1986). “Bilateral Traumatic Leptomeningeal Cysts,” Neurosurgery, 18(3), 386-7.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Saito, A., Sugawara, T., Akamatsu, Y., Mikawa, S. & Seki, H. (2009). “Adult Traumatic Leptomeningeal Cyst-Case Report,” Neurol med chir (Tokyo), 49(2), 62-5

Publisher – Google Scholar

Suri, A. & Mahapatra, A. K. (2002). “Growing Fractures of the Orbital Roof. A Report of Two Cases and a Review,”Pediatr Neurosurg, 36, 96-100.

Publisher – Google Scholar