Discussion

The CSS consists of a cardiovascular symptom complex resulting from excitation of a hyperactive carotid sinus reflex (Hong et al (2000)). It has been reported in patients with head and neck malignancies, paraganglioma and peripheral nerve tumor (Arapakis et al (2004)). To our knowledge, this is the first report of CSS caused by Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Arapakis et al (2004); Ballantyne et al (1975); Rusconi et al (1996); Lopez et al (2000); Venkatraman et al (2005); Takahashi et al (2006)).

The carotid sinus is a dilated segment of the internal carotid arteries, located just superior to the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. Within it arterial adventitia, there are high pressure baroreceptors responsible to regulate blood pressure and heart rate. These receptors are sensitive to stretching of the arterial wall and gives rise to sensory impulses carried via the Sinus Nerve of Hering (which is a branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve) to the nucleus tractus solitarii in the medulla oblongata. The efferent limb of the reflex is carried via vagus and cervical sympathetic nerves to the heart and vessels, controlling heart rate and vasomotor tone (Hong et al (2000); Seifer (2013); Sharma et al (2011)).

When the mean arterial pressure increases, the walls of these vessels passively expand, stimulating firing of these receptors. Stimulation of baroreceptors increases vagal activity and inhibits sympathetic activity. If arterial blood pressure suddenly falls, decreased stretch of the arterial walls leads to a decrease in receptor firing (Hong et al (2000)).

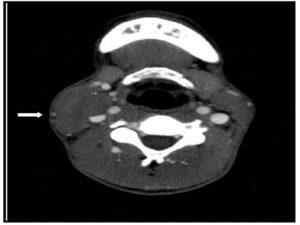

Injury of this sensitive autonomic system is the pathophysiological basis of CSS in our case and other head and neck malignancies. Its etiology is multifactorial, including a mechanical compression of the carotid sinus by tumor mass, impairing blood flow and causing reflex hypersensitization; in addition to compression of glossopharyngeal nerve, which passes between the internal jugular vein and internal carotid artery, creating a triggering focus that renders the entire arc hypersensitive. Other mechanism proposed is the infiltration of the carotid sinus resulting in increased activity of the Hering’s nerve and in the parasympathetic arm of the reflex arc (Hong et al (2000); Lopez et al (2000); Takahashi et al (2006)). It cannot be proved in our case because a histopathological study of the vessel was not performed.

It is also described that depolarization of axons caused by tumor mass neighboring the carotid sinus, with a tendency to stimulate adjacent uninjured axons, can cause CCS (Sobol et al (1982); Hong et al (2000)).. The tumor may cause either a spontaneous abnormal afferent discharge in the damaged nerve itself or may lead to ephaptic conduction, either between glossopharyngeal efferent motor fibers and afferent sinus sensory fibers, or between the glossopharyngeal nerve and other nearby nerves, inducing an abnormally strong carotid sinus reflex (Noroozi et al (2012)).

CSS can be classified according to three types of response to carotid sinus massage: cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity, diagnosed by a greater than or equal to 3-second pause; a vasodepressor response, with the reduction in blood pressure of at least 50 mm Hg in the absence of significant bradycardia; and a third subtype, secondary to the combination of these two mechanisms (Seifer (2013)). There is a transient reduction in cerebral perfusion triggering dizziness and syncope (Seifer (2013); Lopez et al (2000)). In our case there is a mixed response of cardioinhibitory and vasodepressor mechanisms resulting in the combination of bradycardia and peripheral vasculature vasodilatation with hypotension. Syncope was a mild symptom probably because the patient was bedridden while admitted.

The initial treatment includes anticholinergic medications, such atropine, and temporary cardiac pacing, but the definite therapy should always address the underlying cause of CSS (Arapakis et al (2004); Hong et al (2000); Lopez et al (2000); Venkatraman et al (2005); Takahashi et al (2006); Tulchinsky et al (1988)).

References

1. Arapakis, I, Fradis, M, Ridder, G. J., Schipper, J. and Maier, W. (2004) “Recurrent syncope as presenting symptom of Burkitt’s lymphoma at the carotid bifurcation,” Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 113 373-377.

2. Ballantyne, F. III.,VanderArk, C. R. and Hilick, M. (1975) “Carotid sinus syncope and cervical lymphoma,” Wisconsin Medical Journal, 74 91-92.

3. Hong, A. M., Pressley, L. and Stevens, G. N. (2000) “Carotid sinus syndrome secondary to head and neck malignancy: case report and literature review,” Clinical Oncology, 12 (6) 409-412.

4. Humm, A. M. and Mathias, C. J. (2006) “Unexplained syncope–is screening for carotid sinus hypersensitivity indicated in all patients aged >40 years?,” Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 77 1267-1270.

5. Lopez, F. F., Mangi, A. A., Strenger, R, Schiffman, F. J. and Meringolo, R. D. (2000) “B-cell bradycardia: carotid sinus massage by a high-grade lymphoma,” American Journal of Hematology, 64 (3) 232.

6. Moya, A, Sutton, R, Ammirati, F, Blanc, J, Brignole, M, Dahm, J. B. et al. (2009) “Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC),” European Heart Journal, 30 2631-2671.

7. Noroozi, N, Modabber, A, Hölzle, F, Braunschweig, T, Riediger, D, Gerressen M. et al. (2012) “Carotid sinus syndrome as the presenting symptom of cystadenolymphoma,” Head & Face Medicine, 8 31.

8. Rusconi, L. and Zenchi, G. P. (1996) “Carotid sinus syndrome associated with a left parapharyngeal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,” Giornale Italiano di Cardiologia, 26 681-687.

9. Sharma, J. and Dougherty, A. H. (2011) “Recurrent Syncope in a Cancer Patient: A Case Report and Review of the Literature,” Cardiology Research and Practice, 2011 (4) 1-5.

10. Seifer, C. (2013) “Carotid sinus syndrome,” Cardiology Clinics, 31 (1) 111-121.

11. Takahashi, T, Obata, N, Sugawara, N, Fujita, K, Oikawa, K, Yoshimoto, M, et al. (2006) “Carotid sinus syncope in a patient with relapsed cervical lymphoma,” International Journal of Hematology, 84 (1) 92-93.

12. Sobol, S.M., Wood B.G., Conoyer, J.M. (1982) “Glossopharyngeal neuralgia-asystole syndrome secondary to parapharyngeal space lesions,” Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery,” 90 16-19.

13. Tulchinsky, M. and Krasnow, S. H. (1988) “Carotid sinus syndrome associated with an occult primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” Archives of Internal Medicine, 148 (5) 1217-1279.

14. Venkatraman, V, Lee, L. and Nagarajan, D. V. (2005) “Lymphoma and malignant vasovagal syndrome,” British Journal of Haematology, 130 323.