Introduction

Malaysia, in general, is seen as one of the active countries in engaging with the global Corporate Social Responsibility (hereafter, CSR) initiatives and practices. A number of financial and non-financial supports towards local CSR-related programmes and initiatives have been carried out by the country, including CSR national awards, related policies and regulations, tax incentives as well as CSR-related reporting regulations. The introduction of the CSR Framework by Bursa Malaysia in 2006 obviously had made a positive mark towards greater business engagement in CSR management and practice in the nation, which includes CSR-related reporting accountability.

CSR disclosure practices reflect companies’ reporting accountability towards providing information to numerous stakeholder groups. Particularly, CSR disclosures have the potential to strengthen the bond vis-Ã -vis contract between companies and the society at large (Turker, 2009). Hence, these CSR-related potentials and benefits indicate the need for good governance structure in promoting greater disclosure practices (see Bayoud and Kavanagh, 2012). Accordingly, Malaysia had established the Malaysian Code of Corporate Governance 2001 (MCCG 2001) (latest revised code known as the MCCG 2012) and the Bursa Malaysia Revamped Listing Requirements 2001.

Ho and Taylor (2013) discover that the essence strength of the corporate governance (hereafter, CG) in terms of the directors and management highly influences the CSR disclosure practices. The role of CG in managing business-related pressures is be quite challenge despite the types of information that the 3rd party needs which somehow might effect the company’s management behavior and maintaining customers loyalty. As mentioned by Mathews (1995), companies that develop CSR disclosure practice offer several initiatives including good social responsible information may certainly affect their market performance, where it explains the reliable of information the users reached which influence the graph of their market performance. This is supported by Turker (2009) who states that CSR disclosure is a form of business mechanism which facilitates a company’s CSR performance.

Amongst the key reasons for companies’ CSR disclosures are to improve company image (Ramdhony and Oogarah-Hanuman, 2012), and due to continuous stakeholders’ pressures (Bayoud and Kavanagh, 2012). Particularly, Esa and Mohd Ghazali (2012) mention that the association between CSR disclosure and corporate governance may lead to long term business value thus promoting efficient business operations and users’ acceptance. Hence, the roots of generating a high quality CSR disclosure is CG itself, which subsequently will accelerate better governance (Adam and Shavit, 2009).

Based on the above discussions, thus, this study seeks to investigate the possible links between CG mechanisms and CSR-related disclosures, particularly with a focus on the key CSR dimensions, i.e. Marketplace, Workplace, Community and Environment. The findings of this study may offer some insights to the relevant policymakers, including the Bursa Malaysia and other regulatory and professional bodies, to improve current CSR strategies towards promoting greater CSR disclosure engagement amongst Malaysian companies. Additionally, the study findings may put forward some preliminary ideas relating to the appropriate CG aspects in enhancing specific and worthy CSR disclosures practices by the industry players.

Literature Review

Underpinning Theoretical Perspectives

Stakeholder theory is one of the key theoretical perspectives found to be relevant in understanding companies’ CSR-related disclosure behaviour towards fulfilling the interest and demands for information by various stakeholders (see Roberts, 1992; Hooghiemstra, 2000, Figar and Figar, 2011). Cecil (2010) argues that non-financial matters are growingly becoming crucial to the sustainable development of companies, and that disclosure practice functions as an essential approach to communicate the CSR effects of organizations’ economic actions. Apart from that, disclosing CSR information signifies companies’ execution of their accountability and good governance, as well as CSR-related programmes and activities for both their external and internal stakeholders. Stakeholder theory posits the dynamics of the interrelationship between a company and its business environment, which emphasised responsibility and accountability (Gray et al., 1996). This theory affirms that:

‘…corporations continued existence requires the support of the stakeholders and their approval must be sought and the activities of the corporation adjusted to gain that approval. The more powerful the stakeholders, the more company must adapt. Social disclosure is thus seen as part of the dialogue between the company and its stakeholders. (Gray et al., 1995, p. 53)

Stakeholder theory positions companies as the central point of stakeholders’ circle of relationships. In a specific time period, a company will have relationships with two core stakeholder groups; often known as internal and external, or key and secondary (see Freeman and Reeds, 1983; Clarkson, 1995).

Agency theory is also a relevant notion to comprehend the possible association between CSR disclosure and CG. Jensen and Meckling (1976) argue that in a business setting, there exist a contract between one or more persons (the principal/s) and another person (the agent) to perform certain matters on their behalf, thus, involves delegation of decision-making authority to the respective agent. The management is the essential group of people who has the opportunity to enter into a contractual relationship with other stakeholders; hence, they are company’s ‘agents’ (Hill and Jones, 1992). They are also responsible (on behalf of their principals) for monitoring business operations, achieving company’s goals in addition to maximizing shareholders’ wealth. Strict control and monitoring business mechanism is an important initiative in avoiding a breach of action hence capable to control agency problems and safeguard managers’ action in the best interests of their shareholders (see Ho and Wong, 2001).

CG mechanisms including board of directors are crucial for a progressive disclosure practice (see O’Sullivan et al., 2008). Frolova and Lapina (2015) contend that a successful business-CSR requires the establishment of a separate management system i.e. an effective board of directors who supports CSR disclosure practices. Additionally, Garvare and Johansson (2010) describe the benefit of a relationship between board of directors and CSR in fulfilling stakeholders’ needs and demand. From a local setting, Ho and Taylor (2013) highlight the potential of companies in Malaysia through strong CG structure to stimulate voluntary disclosure practices. In relation to this, Darus et al. (2013) conclude that larger board is relevant in mitigating agency problems caused by information asymmetry; this also influences businesses to adopt new guidelines in improving CSR initiatives.

Consequently, the literature points out the relevancy for these theories to underpin the investigation concerning CSR disclosures and CG.

CSR Key Dimensions

The Bursa Malaysia CSR Framework requires all publicly listed companies to clearly define their sustainability strategies and objectives, and accordingly make appropriate disclosures of companies’ CSR-related information. Four key CSR dimensions that should be followed and balanced in order to reflect companies’ sustainability objectives include community, workplace, marketplace and environmental. Summaries for the disclosures according to these dimensions are as follows:

Community: companies’ engagement with activities involving the communities, including supporting education, donations and organizing youth development programs; with the aim to create bonds with the communities and focus on their welfare and benefits.

Workplace: maintain employees’ welfares towards greater productivity and quality, including quality of working environment, safety and health, and human and labour rights.

Marketplace: formulation of activities aiming to encourage stakeholders, such as shareholders, suppliers, vendors and customers to act sustainably through the value chain relationships thus support the company’s sustainability agenda.

Environment: environmentally-related policies and activities involving matters of energy, bio-fuels, biodiversity, preservation of the flora and fauna as well as other sustainability business practices.

CSR Disclosure Practice: The Benefits and Relationships with CG

Prevailing literature has explored the possible benefits of CSR disclosure practices to companies. Fombrum et al. (2000), for instance, discover that CSR-related disclosures improve business ability to attract resources, enhance performance and develop competitive advantages while satisfying stakeholders’ needs. CSR disclosures also have the ability to determine company’s reputation (e.g. Ramdhony and Oogarah-Hanuman, 2012), increase the “licence to operate” and enhance business sustainability (Hamid et al., 2007; Herbohn et al., 2014), and improve financial performance (Janggu et al., 2007; Yusoff et al., 2013). These studies infer the notion that CSR disclosures have much to offer to individual company, next to the entire business industry hence the national economic and social sustainability.

Good CG generally may lead to practice of fairness, transparency, and accountability in managing business organizations. Black et al. (2002) found that strong CG will enhance operating performance through improved efficiency of operations. In view of that, Esa and Mohd Ghazali (2012) comment on the strong association between CSR disclosure and CG which will result in positive long-term business values, efficient business operations and user acceptance. Michelon and Parbonetti (2012) who studied the potential of CG to influence sustainability disclosures amongst US and European companies had resulted with an affirmative association between community influential and disclosure practice. Cormier, Lapointe-Antunes and Magnan (2015) specifically learnt that good corporate responsibility relies highly on top management strong leadership. Apart from that, they also discover that CG strategic framework should encompass clear identification of key issues, stakeholders, and spheres of influence establishment of relevant policies and procedures as well as active stakeholder engagement.

Previous studies had also focused on the potential links between CG and corporate reporting practice. Amongst the prominent CG variables studied to be linked with CSR disclosures include board independence, board size, board meetings and board gender. De Villiers, Naiker, and van Staden (2011) reveal that companies with higher percentage of independent board members, more legal experts in the board, more active CEOs in the board, and a lower dual role of board members as board chairman are significantly correlated with strong environmental performance. Other studies such as Norita and Shamsul (2004) and Albawwat and Ali Basah (2015) also discovered that board independence is positively related with voluntary disclosures. Nevertheless, Habbash (2016) who studied CSR disclosure practice in Arab, Bukair and Abdul Rahman (2015) who studied the disclosure practice in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Abdul Razak and Mustapha, a study on the Malaysian disclosure practices had found insignificant link between board independence and CSR disclosures.

A strand of studies also discovers that board size is closely linked to greater CSR disclosures; among others are Said, Yuserrie and Haron (2009), Esa and Mohd Ghazali (2012), Darus et al. (2013), Bukhari, Awan and Ahmed (2013) and Yusoff et al. (2015). Majeed, Aziz and Saleem (2015) who studied the CSR disclosure practices of the Pakistan companies also ascertained significant link between the two variables. These findings imply that greater size of the board of directors in a company will lead to higher extent of CSR disclosure. Accordingly, Akhtaruddin, Hossain, Hossain and Yao (2009) highlight that the collective experience and expertise of the board are pertinent to the decision for disclosure practice.

It is also interesting to examine whether the frequency of board meeting has any influence on a company’s CSR disclosure practice. Board meeting signifies the commitment of the board member to strategize and make decision, including business-CSR matters. In relation to this, Giannarakis’ (2014) study has resulted with positive and significant relationship between board commitment and business disclosure practice. Prior literature offers some insights about how the presence of female directors on the board may influence board decisions (e.g. Fodio and Oba, 2012; Rao, Tilt and Lester, 2012). Williams (2003) in particular found that the presence of female directors on the board has the potential to influence companies’ involvement in CSR related activities. Such a finding seems to be connected with female directors’ distinctive psychological characteristics that accommodate stakeholders’ needs and demands. Rao et al. (2012), for instance, revealed that female board of directors in Australia welcome greater environmental reporting.

Based on the above discussed literature, the followings hypotheses are developed

|

H1

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board independence and CSR disclosure.

|

|

|

H1a

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board independence and Marketplace disclosure.

|

|

H1b

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board independence and Workplace disclosure.

|

|

H1c

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board independence and Community disclosure.

|

|

H1d

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board independence and Environment disclosure.

|

|

H2

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board size and CSR disclosure.

|

|

|

H2a

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board size and Marketplace disclosure.

|

|

H2b

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board size and Workplace disclosure.

|

|

H2c

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board size and Community disclosure.

|

|

H2d

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board size and Environment disclosure.

|

|

H3

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board meetings and CSR disclosure.

|

|

|

H3a

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board meetings and Marketplace disclosure.

|

|

H3b

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board meetings and Workplace disclosure.

|

|

H3c

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board meetings and Community disclosure.

|

|

H3d

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board meetings and Environment disclosure.

|

|

H4

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board gender and CSR disclosure.

|

|

|

H4a

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board gender and Marketplace disclosure.

|

|

H4b

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board gender and Workplace disclosure.

|

|

H4c

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board gender and Community disclosure.

|

|

H4d

|

There is a significant positive relationship between board gender and Environment disclosure.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Methodology

Content analysis has been carried out on the annual reports of 85 non-financial companies covering a 3-year time frame (2011 to 2013), thus a total observation of 255 company case. The total sampled companies were selected based on the systematic stratified random sampling approach. A disclosure checklist which consisted of 31 items has been developed based on prior literatures and Bursa CSR framework. The CSR disclosure items in the four key dimensions have been collected using the disclosure-rating used in Sumiani et al. (2007), and Yusoff and Lehman (2008). The ratings of CSR disclosure items are as follows:

General disclosure = scored as ‘1’

Qualitative disclosure = scored as ‘2’

Quantitative disclosure = scored as ‘3’

Combination of qualitative and quantitative disclosure = scored as ‘4’.

The independent variables used in this study were board independence, board size, board meetings and board gender. The justifications for such a selection of variables are based on these notions:

Board independence: to measure board effectiveness and to determine the board quality as socially responsible or non-responsible firms (Webb, 2004). This variable is measured based on the proportion of non-executive directors to total directors.

Board size: to measure the effectiveness, coordination, communication and decision-making by looking at the board size (Jensen, 1993; Astrachan et al., 2006). Board size is measured based on the number of board of directors in the company.

Board meetings: focused on the board diligence and the level of monitoring on the implementation of the company’s activities (Laksamana, 2008; Giannarakis, 2014). Board meeting is measured based on the number of board meetings held a year in a company.

Board gender: male and female directors are deemed to play different roles in companies’ decision-making, especially on issues relating to CSR management and practice (Giannarakis, 2014). The board gender is measured based on the percentage of directors’ gender to total directors on board.

These dependent and independent variables of the study are gathered from the sampled companies’ annual reports, whilst the control variables, i.e. profitability, company size and sales were collected via Data Stream Thompson. Study analysis was run using the SPSS version 20. Multiple regression models were applied to conform to the aim of this study i.e. to examine the possible relationships between CG and CSR disclosure practice. The use of the regression model was based on the linear relationship predicted for the two variables studied. Also, the regression model has the advantage of producing study outcomes that are easily interpretable and understandable. Accordingly, the following five models have been identified:

Model 1

CSRDS = βₒ + βâ‚INDs + β₂BodSize + βᴣBMeetings + β4BGender + β5Size + β7Lev + ε

Model 2

CSRDC = βₒ + βâ‚INDs + β₂BodSize + βᴣBMeetings + β4BGender + β5Size + β7Lev + ε

Model 3

CSRDW = βₒ + βâ‚INDs + β₂BodSize + βᴣBMeetings + β4BGender + β5Size + β7Lev + ε

Model 4

CSRDM = βₒ + βâ‚INDs + β₂BodSize + βᴣBMeetings + β4BGender + β5Size + β7Lev + ε

Model 5

CSRDE = βₒ + βâ‚INDs + β₂BodSize + βᴣBMeetings + β4BGender + β5Size + β7Lev + ε

Where:

CSRDS = Total CSR disclosures

CSRDC = CSR disclosures on Community dimension

CSRDW = CSR disclosures on Workplace dimension

CSRDM = CSR disclosures on Marketplace dimension

CSRDE = CSR disclosures on Environment dimension

βINDs = Proportion of INDs to total directors

BodSize = Number of directors on the board

BMeetings = Number of board meetings in the year

BGender = Number of gender on the board

Size = Total sales

Lev = Debt Ratio

ε = Error term

Research Findings

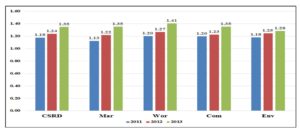

It has been found that there is a gradual increase in the total scores of CSR disclosures made by the sampled companies, over the three years period of study (refer Figure 1).

The increase in disclosure practice is evident for all four CSR dimensions. Nevertheless, ‘environmental’ dimension showed the least percentage of progression between 2011 and 2013.

Figure 1 Average Score for CSR Disclosures (2011-2013)

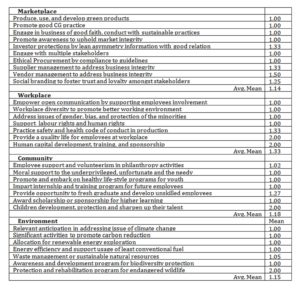

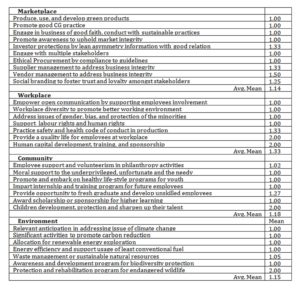

Table 1 provides the average mean scores for all CSR disclosures according to the key dimensions. Generally, the CSR disclosure reporting for the three years is considered low despite the gradual increased trend, as depicted in Figure 1 above. All CSR items have resulted to fall under the range of ‘descriptive’ and ‘qualitative’ form of disclosures (score between 1 and 2). Among the four dimensions, workplace-related disclosures ranked first, with a total mean score of 1.33; followed by Community, Environmental and Marketplace disclosures. Overall, the study variables have been found to be normally distributed, and that there was no evidence of multicollinearity problem. Hence the data used in this study were suitable for further analysis.

Table 1: Average Mean Scores for CSR Items According to Dimensions

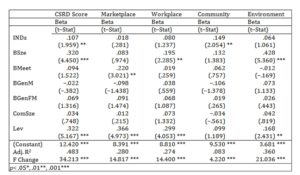

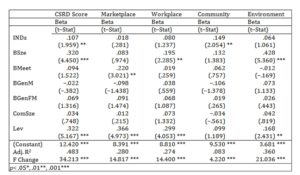

Table 2 presents the results of the regression analyses performed. All five models have been found to be significant (i.e. F. Change was significant at the .001 level). The Adjusted R-Squares for all five models are .483, .280, .274, .083, .360; which explain the variation in CSR disclosure practice based on the key dimensions and have been influenced by all CG proxies. Generally, these results indicate the significant influence of board-related decision-making mechanism on the companies’ CSR disclosure practices.

Table 2 Regression Analyses: CSR Disclosures and CG Mechanisms

Table 2 also shows that Board independence has been discovered to highly influence greater CSR disclosure practice, and in particular, significance influence on the Community-based information (see also, Jo and Harjoto, 2011). With regards to the Board size, the first model showed a significant positive relationship of this variable with CSR disclosures. Specifically, this variable has positive significant correlation with the Workplace and Environmental-based information. Such a finding signifies the extent of companies’ efforts to fulfill stakeholders’ demands for CSR information. Esa and Mohd Ghazali (2012) comment that the existence of wider board expertise and knowledge may create unanimous decision-making and effective communication among the directors; in which, it represents one of the effective ways to mitigate the agency conflict.

Board meeting has been found to have a positive significant influence only on the Marketplace dimension, whereas the Environmental dimension is seen to have an insignificant and negative relationship. CSR-Marketplace information is closely related to companies’ internal policies, thus justifies the need for higher number of discussions amongst the board members (see Giannarakis, 2014). With respect to Board gender, both male and female board members are found to have insignificant influence on CSR disclosures. This finding contradicts the study by De Cabo, Gimeno and Escot (2011) and Francoeur et al. (2008) which argue that women directors are able to provide new skills and abilities to the board, hence facilitate the decision-making process. These findings further conclude that the accepted results for the study hypotheses are related to H1, H1c, H2, H2b, H2d and H3a.

Conclusion

Overall, despite a slight progression, the CSR disclosure practices for the three years of study have been found to be rather low and ‘simplistic’. The research findings also offer some knowledge that pertains to the extent of link between the selected CG mechanisms and CSR disclosure information according to four key dimensions, and the relevancy of Stakeholder and Agency theories. Specifically, positive significant results have been found for the relationships relating to board independence-community, board size-workplace and environment, and board meetings-marketplace. These findings put forward some preliminary ideas about the CG-related strategies towards enhancing the quality of CSR disclosures thus imply the potentials of CG mechanisms in promoting greater implementation amongst companies in Malaysia.

Three recommendations may be applicable for future research. First, an extended research study may be carried out using the samples of award winning companies; based on the justification to investigate the most disclosed information according to the CSR dimensions. Second, other influencing factors for CSR disclosures may be tested against the disclosures in the dimensions. Such a study may further offer ideas pertaining to the business strategies towards greater local CSR disclosure practice. Third, since the data set contains both a cross-sectional and time series dimension, future study may use panel data regression analysis as an alternative quantitative approach to complement the results of this study.

Acknowledgment

The researchers would like to thank Accounting Research Institute (ARI) HiCOE and Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (MOHE) for the research grant received.

References

- Abdul Razak, S. E. and Mustapha, M. 2013, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures and Board Structure: Evidence from Malaysia’, Jurnal Teknologi (Social Sciences), 64(3), 73-80.

Google Scholar

- Adam, A.M. and Shavit, T. 2009, ‘Roles and Responsibilities of Boards of Directors Revisited in Reconciling Conflicting Stakeholders Interests While Maintaining Corporate Responsibility’, Journal of Management & Governance, 13(4), 281-302.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Akhtaruddin, M., Hossain, M. A., Hossain, M., and Yao, L. 2009, ‘Corporate Governance and Voluntary Disclosure in Corporate Annual Reports of Malaysian Listed Firms’, Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research. 7(1), 1-19.

- Albawwat, A.H. and Ali Basah, M.Y. 2015, ‘Corporate Governance and Voluntary Disclosure of Interim Financial Reporting in Jordan’, Journal of Public Administration and Governance, 5(2), 100-127.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Astrachan, J.H., Keyt, A., Lane, S. and Mcmillan, K. 2006, ‘Generic Models for Family Business Boards of Directors,’ in P. Zata Poutziouris, K.X. Smyrnios S.B. Klein. Cheltenham, Handbook of Research on Family Business, Edward Elgar, Northampton.

- Bayoud, N. S. and Kavanagh, M. 2012, ‘Corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from Libyan managers’, Global Journal of Business Research, 6(5), 73-83.

- Black, B., S. Jang, and W. Kim, W, 2002, ‘Does Corporate Governance Predict Firms’ Market Values? Evidence from Korea’, Stanford Law School, Working Paper No. 237.

- Bukair, A.A. and Abdul Rahman, A. 2015, ‘The Effect of the Board Of Directors’ Characteristics on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure by Islamic Banks’, Journal of Management Research, 7(2), 506-519.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Bukhari, K.S., Awan, H.M. and Ahmed, F. 2013, ‘An Evaluation of Corporate Governance Practices of Islamic Banks vs. Islamic Bank Windows of Conventional Banks: A Case of Pakistan’, Management Research Review, 36, 400—416.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Cecil, L. 2010, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in the United States’, McNair Scholars Research Journal, 1(1), 43-52.

- Clarkson, M. E. 1995, ‘A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance’. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92-117.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Cormier, D., Lapointe-Antunes, P. and Magnan, M. 2015, “Does Corporate Governance Enhance the Appreciation Of Mandatory Environmental Disclosure by Fnancial Markets?”, Journal of Management & Governance, 19, 897—925.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Darus, F., Mat Isa, N.H. and Yusoff, H. 2013, ‘Corporate Governance and CSR: Exploring the Application of ISO 26000 in An Emerging Market’, International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 2(2), 333-348.

- De Cabo, R.M., Gimeno, R. and Escot, L. 2011, ‘Disentangling Discrimination On Spanish Boards Of Directors’. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 19(1), 77—95.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- De Villiers, C., Naiker, V. and van Staden, C.J. 2011, ‘The Effect of Board Characteristics on Firm Environmental Performance’, Journal of Management, 37(6), 1636-1663.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Esa, E., and Mohd Ghazali. N. A. 2012, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Governance in Malaysian Government-Linked Companies’. Corporate Governance, 12(3), 292-305.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Figar, N. and Figar, V. 2011, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility in the Context of the Stakeholder Theory’, FACTA UNIVERSITATIS, Series: Economics and Organization, 8(1), 1—13.

- Fodio, M. I. and Oba, V. C. 2012, ‘Gender Diversity in the Boardroom and Corporate Philanthropy: Evidence from Nigeria’, SSRN 2166544.

- Fombrun, C. J., Gardberg, N. A. and Sever, J. M. 2000, ‘The Reputation Quotient SM: A Multi-Stakeholder Measure of Corporate Reputation’, The Journal of Brand Management, 7(4), 241-255.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Francoeur, C., Labelle, R. and Sinclair-Desgagné, B. 2008, ‘Gender Diversity in Corporate Governance and Top Management’, Journal of Business Ethics, 81(1), 83—95.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Freeman, R. E. and Reed, D. L. 1983, ‘Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance’. California Management Review, 25(3), 88-106.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Frolova, I. and Lapina, I. 2015, ‘Integration of CSR Principles in Quality Management’, International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 7(2/3), 260-273.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Garvare, R. and Johansson, P. 2010, ‘Management for Sustainability — A Stakeholder Theory’, Total Quality Management, 21(7), 37-744.

- Giannarakis, G. 2014, ‘Corporate Governance and Financial Characteristic Effects on the Extent of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure’, Social Responsibility Journal, 10 (4), 569—590.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Gray, R., Kouhy, R. and Lavers, S. 1995, ‘Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting: A Review of the Literature and a Longitudinal Study of UK Disclosures’, Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8 (2), 47-77.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Gray, R., Owen, D. and Adams, C. 1996, Accounting & Accountability: Changes and Challenges in Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting. London New York: Prentice Hall.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Habbash, M. 2016, ‘Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia’, Journal of Economic and Social Development, 3(1), 87-103.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Hamid, F. Z. A., Fadzil, F. H. H., Ismail, M. S. and Ismail, S. S. S., ‘CSR and Legitimacy Strategy by Malaysian Companies’, In M. N. M. Ali, M. R. M. Ishak, N. Y. M. Yusof & M. Y. Yusoff (Eds.), Corporate Social Responsibility: Our First Look. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Institute of Integrity, 2007.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Herbohn, K., Walker, J. and Loo, H.Y.M. 2014, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility: The Link Between Sustainability Disclosure and Sustainability Performance’, Abacus, 50(4), 422—459.

- Hill, C.W.L. and Jones, T.M. 1992, ‘Stakeholder-Agency Theory’, Journal of Management Studies, 29(2), 131-154.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Ho, P.L. and Taylor, G. 2013, ‘Corporate Governance and Different Types of Voluntary Disclosure’, Pacific Accounting Review, 25(1), 4 — 29.

Publisher – Google Scholar

- Ho, S.S. and Wong, S. K. 2001, ‘A Study of the Relationship Between Corporate Governance Structures and the Extent of Voluntary Disclosure’, Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 10(2), 139—156.

- Hooghiemstra, R. 2000, ‘Corporate Communication and Impression Management — New Perspectives Why Companies Engage in Corporate Social Reporting’, Journal of Business Ethics, 27(1-2), 55-68.

- Janggu, T, Joseph, C and Madi, N 2007, ‘The Current State of Corporate Social Responsibility Among Industrial Companies in Malaysia’, Social Responsibility Journal, 3(3), 9-18.

- Jensen, M. C. 1993, ‘The Modern Industrial Revolution, Exit, and the Failure of Internal Control Systems’, Journal of Finance, 48, 831-880.

- Jensen, M.C. and Meckling, W.H. 1976, ‘Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure’, Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360.

- Jo, H. and Harjoto, M. A. 2011, ‘Corporate Governance and Firm Value: The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility’, Journal of Business Ethics, 103, 352-383.

- Johnson, S., Boone, P., Breach, A. and Friedman, E. 2000, ‘Corporate gGovernance in the Asian Financial Crisis’, Journal of Financial Economics, 58, 141-186.

- Laksmana, I. 2008, ‘Corporate Board Governance and Voluntary Disclosure of Executive Compensation Practices’, Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(4), 1147-1182.

- Majeed, S., Aziz, T. and Saleem, S. 2015, ‘The Effect of Corporate Governance Elements on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure: An Empirical Evidence from Listed Companies at KSE Pakistan’, International Journal of Financial Studies, 3, 530-556.

- Mathews, M.R. 1995, ‘Social and Environmental Accounting: A Practical Demonstration Of Ethical Concern?’, Journal of Business Ethics, 14(8), 663-673.

- Michelon, G. and Parbonetti, A. 2012, ‘The Effect of Corporate Governance on Sustainability Disclosure’, Journal of Management & Governance, 6, 477—450.

- Norita, M.N. and Shamsul, N. A. 2004. Voluntary Disclosure and Corporate Governance among Financially Distressed Firms in Malaysia, The Electronic Journal of the Accounting Standards Interest Group of AFAANZ, Vol. 3 No 1, available at: http://www.cbs.curtin.edu.au/files/nasir-abdullah.pdf [accessed 1 September 2015].

- O’Sullivan, M., Percy, M. and Stewart, J. 2008, ‘Australian Evidence on Corporate Governance Attributes and Their Association with Forward-Looking Information in the Annual Reports’, Journal of Management and Governance, 12(1), 5-35.

- Ramdhony, D. and Oogarah-Hanuman, V. 2012, ‘Improving CSR Reporting in Mauritius Accountants’ Perspectives’, World Journal of Social Sciences, 2(4), 195-207.

- Rao, K.K., Tilt, C.A. and Lester, L.H. 2012, ‘Corporate Governance and Environmental Reporting: An Australian Study’, Corporate Governance, 12(2), 143-163.

- Rashidah, A.R, and F. Haneem, M.A. 2006, ‘Board, Audit Committee, Culture and Earnings Management: Malaysian Evidence’, Managerial Auditing Journal, 21 (7), 783-804.

- Roberts, R. W. 1992, ‘Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: An Application of Stakeholder Theory’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(6), 595-612.

- Said, R., Yuserrie, H.Z. and Haron, H. 2009, ‘The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Corporate Governance Characteristics in Malaysia Public Listed Companies’, Social Responsibility Journal, 5, 212—226.

- Sumiani, Y., Haslinda, Y. and Lehman, G. 2007, ‘Environmental Reporting in A Developing Country: A Case Study on Status and Implementation in Malaysia’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 15, 895-901.

- Turker, D. 2009, ‘Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study’, Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 411-427.

- Webb, E. 2004, ‘An Examination of Socially Responsible Firms’ Board Structure’, Journal of Management and Governance, 8, 255-77.

- Yusoff, H. and Lehman, G. 2008, ‘International Differences on Corporate Environmental Accounting Developments: A Comparison Between Malaysia and Australia’, Accounting and Finance in Transition, 4, Greenwich University Press, 92-124.

- Yusoff, H., Darus, F. and Rahman, S.A.A. 2015, ‘Do Corporate Governance Mechanism Influence Environment Reporting Practices? Evidence from an Emerging Country’, International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 10(1), 76-96.

- Yusoff, H., Mohamad, S.S. and Darus, F. 2013, ‘The Influence of CSR Disclosure Structure on Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence From Stakeholders’ Perspectives’, Procedia Economics and Finance, International Conference on Economics and Business Research 2013 (ICEBR 2013), 7, 213-220.