Introduction

Excessive indebtedness has been pointed out as a risk for the country’s financial sustainability (Bolívar et al., 2016; Cabaleiro et al., 2013; Christiaens et al., 2010; Cohen & Karatzimas, 2015; Oulasvirta, 2014; Pérez-López et al., 2013), which has led to calls for governments’ actions to control debt (European Parliament, 2009; European Commission, 2019; International Monetary Fund, 2014).

These concerns led the European Union to issue the Directive 2011/7/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, on combating late payment in commercial transactions, as a policy on short-term financial sustainability. The Late Payments Directive (LPD) set up that public entities must pay within a period of up to 30 days, also requiring that the Member States develop reporting mechanisms about their performance as regards the payment period (PP).

However, not only the implementation of the LPD is assessed through a single measure (the PP), but also the Directive does not establish the methodology to be applied for this purpose. This may limit the comparability among the Member States (European Parliament, 2018), and brings to the discussion whether governments are changing their behaviour on this matter or just creating the illusion of better performances (e.g., Bevan & Hood, 2006; Chen, 2023; Gao et al., 2021; Irwin, 2012; Kroll & Vogel, 2021; Pierre & Licht, 2021). In this latter case, this process is known in the literature as “gaming”, which, according to Kroll and Vogel (2021, p. 165), consists of “generating positive performance data without achieving the actual objective behind the indicator”.

The European Commission is responsible for monitoring the LPD implementation to ensure that Member States are accountable and transparent regarding their public entities’ performances concerning the PP. This monitorization already led the Commission to request actions to be taken by several Member States (such as Greece, Italy, Slovakia, and Spain).

Portugal has been struggling with indebtedness for decades, being subject to an international Financial Assistance Programme (FAP) between 2011 and 2014. Late payments have been a chronic problem in Portugal, which is one of the countries with higher levels of PP, based on the 129 days found for this ratio in 2015 (European Parliament, 2018). Consequently, in 2017, the European Commission notified the country for not complying with the LPD.

Several authors stressed that the PP may be underestimated, not reflecting the real performances on this matter by the Portuguese local governments (Baleiras et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2021; Santos & Martinho, 2020). It is worthwhile to mention that Portugal has already been pointed out as an example of using accounting for gaming (Irwin, 2012).

Furthermore, the quarterly basis applied in Portugal, instead of a monthly one, as it has been applied in Spain, for instance, may be beneficial to local entities. This can be explained by an additional 90 days for payment with no relevant consequences to them, since the suppliers’ debt (SD) is only included as a balance at the end of the quarter, regardless of the acquisition date within this gap.

In what concerns local governments, and contrary to other governmental subsectors, the Portuguese methodology for measuring their performance as regards the PP does not consider all the liabilities’ accounts. Therefore, this exploratory analysis aims to assess whether there is evidence of possible gaming strategies by local governments using different categories of liabilities to convey a better image of the Portuguese performance regarding the PP. Data from 308 Portuguese local governments were gathered for the period between 2014 and 2019, which was the last year available in what concerns the PP. Descriptive and Pearson correlation analyses are used for this purpose.

Despite gaming has become a global phenomenon in performance management (Gao et al., 2021), research has not focused on the gaming behaviours of public organizations (Chen, 2023). This paper aims to fill this research gap by using data from the Portuguese local governments’ performance regarding PP and, more specifically, the liabilities’ components as the object for assessing a possible use of gaming strategies by them.

Therefore, the outputs from this paper may contribute to different stakeholders interested in the information provided by the Portuguese local governments, which may include the central government, academics, analysts, and other national authorities, such as national statistics, regulators and supervisors. Besides, from a broader perspective, it can be relevant to those similarly interested parties from a European level.

The next section presents the material and methods underlying the analysis proposed for this paper.

Material And Methods

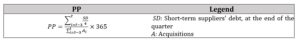

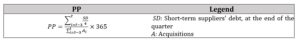

The LPD entered into force through the Portuguese Decree-Law 62/2013, on May 10, being the PP methodology defined by the Resolution of the Ministers Council (RMC) 34/2008, on February 22, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Methodology for calculating PP in Portugal

Source: Adapted from RMC 34/2008.

The RMC 34/2008 also sets up what is considered SD and acquisitions (A) throughout the Public Sector, which is not harmonized. For instance, the SD is not consistent between the public companies or health sector entities and the local governments, given the latter does not consider the ‘other debts’ (OD) for calculating PP.

Law 73/2013, on September 3, establishes in article 52 how to measure the local governments’ total debt, which includes loans, leasing contracts and any other debts to financial institutions, as well as all other debts arising from budgetary operations. Since OD is not being considered within the PP, it raises the question concerning the proper classification of short-term suppliers’ debt arising from budgetary operations.

Furthermore, the Portuguese methodology for measuring the local government performance as regards the PP does not consider all the liabilities’ accounts. Then, the analysis proposed in this paper assesses the different categories of liabilities to identify which of them seem to be more associated with the local governments’ indebtedness level.

For this purpose, it uses the total debt (TD) as the reference variable proposed, which comes from the Directorate-General for Local Authorities (DGAL in the Portuguese Acronym) under Law 73/2013. The remaining variables were selected from those which may have a potential association with the Portuguese local governments’ debt, as follows:

- Short-term suppliers’ debt (SD), as considered by RMC 34/2008;

- Other debts (OD), as defined by RMC 34/2008, but not considered for the PP.

Data were gathered from the DGAL website. The study focuses on the 308 Portuguese local governments from 2014 to 2019 for the reporting period that ended on December 31 of each one of those years. It should be stressed that, regardless of the obligation to report the PP quarterly, the last information available for local governments is for December 2019. This may be possibly explained by the adoption of the newest Portuguese accounting standards (SNC-AP, in the Portuguese Acronym) to be applied by local governments from 2020 onwards. Based on the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS), its adoption requires that all government subsectors apply the same accounting framework.

As analysis techniques, this study is essentially based on descriptive statistics, and Pearson correlation analysis, the latter to identify the sign and level of association between TD and all the other variables (SD, and OD).

The next section presents the findings from this research.

Results

Figure 1 provides data on the average PP of the Portuguese local governments from 2014 to 2019, with a further breakdown by those that comply or do not comply with the 30 days threshold for that measure.

Figure 1. Average PP of the Portuguese local governments (2014 to 2019)

Source: Own elaboration

Data from Figure 1 show that the average PP for the Portuguese local governments has decreased over the period, with the most significant decrease recorded from 2014 to 2015 (36 days or 33.6%). The Portuguese local governments that do not comply with the threshold have been those that mostly contribute to this since the subgroup that complies shows a stable level for the average PP over the period (about 13 days).

Figure 2, in turn, shows the evolution in the percentage of local governments that comply, or do not, with the LPD.

Figure 2. Portuguese local governments by PP up to and higher 30 days

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 2 indicates that most of the Portuguese local governments did not comply with the LPD target of 30 days in 2014 (54%), the last year of the FAP. From 2015 onwards, where the major decrease can be seen again, a different scenario can be found. Therefore, 37% of Portuguese municipalities did not comply with the PP threshold in 2019, which means that almost two-thirds (63%) of them already complied with the PP threshold for this year.

Following, Figure 3 shows the evolution of the average SD and the average OD in the local governments that pay within 30 days and in those that have a higher PP.

Figure 3. Average SD and OD (in 106 Euros) of the Portuguese local governments (2014 to 2019)

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 3 shows that the local governments that comply with the 30 days threshold have higher levels of OD in comparison to SD, particularly between 2014 to 2017. Conversely, the SD has been always presenting higher levels for the local governments with a PP higher than 30 days.

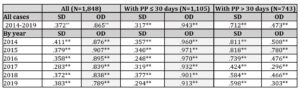

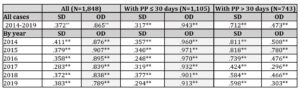

As the OD is not considered within the PP, Table 2 presents Pearson correlation coefficient values and their significance levels to assess how the TD is potentially related to the different categories of liabilities (SD, and OD). For this purpose, the analysis provides information for the entire sample as well as with two breakdowns: local governments with a PP that complies with the 30 days threshold and those who do not comply with this. To improve the readability, the higher levels of correlations between those variables and the TD are identified in grey light (for figures equal to or higher than 0.7).

Table 2. Pearson correlation between TD, SD, and OD

** The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Source: Own elaboration

Table 2 indicates that the TD has, globally, lower levels of correlation with the variable SD, which is particularly evident for local governments where the PP complies with the 30 days threshold. Conversely, all other variables have higher levels of correlation with the TD for this group, namely the OD. The periods for which the correlations between the TD and the SD have higher levels (particularly from 2014 to 2016) can be only found for those local governments where the PP is above the threshold used as a reference.

The next section presents the main conclusions from this study, as well as its limitations, and future avenues.

Conclusion

Concerns with the government’s indebtedness led the European Commission to issue the LPD to discourage the culture of late payments that put at risk their financial sustainability. Thereby, the LPD stated that commercial transactions should be paid within 30 days and the LPD implementation is assessed based on the PP.

Despite the European Commission’s intention to hold Member States accountable and transparent concerning public entities’ payment behaviour, they assess the LPD compliance based on a single measurement, the PP, for which a methodology to measure it was not settled up. This situation was kept even when the European Commission was confronted with examples of Member States, such as Spain, whose methodology was incompatible with LPD.

The Portuguese local governments’ PPs have been reducing, with most of them complying with the 30 days limit imposed by the Directive since 2015 (the year after finishing the FAP). Notwithstanding, the question of whether they are more efficient at paying or whether they are just giving the “illusion” of it remains.

The Portuguese methodology for measuring the PP not only grants an additional period of up to 90 days, but it does not consider the OD. This exploratory research provides preliminary evidence that those debts have statistically significant relations with the TD, with higher levels of correlation for those local governments that comply with the LPD. Furthermore, the SD, which is the variable explicitly considered in the methodology, has only higher levels of correlation with the TD for a specific period observed for those local governments with a PP above the LPD threshold. Therefore, the findings may suggest the existence of gaming strategies by the local governments, which allows them to report a positive change in their performance as regards the PP and, consequently, comply with the LPD, as suggested by the literature (Androniceanu, 2021; Caamano-Alegre et al., 2013; Ehalaiye et al., 2020; Krueathep, 2014; Zafra-Gomez et al., 2009; Zuccolotto & Teixeira, 2014).

It may be pointed out, as a main limitation of the study, the data reliability, which cannot be assured, as the website of DGAL disclaims on this purpose that the local governments are responsible for it.

As future avenues, research with further and more robust quantitative analysis methods could improve the evidence from this exploratory study. Furthermore, a cross-country comparison using data from other European Union countries would increase the contribution of the analysis proposed in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa (IPL/2022/WES_ISCAL).

References

- Androniceanu, A. (2021) ‘Transparency in public administration as a challenge for a good democratic governance,’ Administratie si Management Public, 36, 149-164.

- Baleiras, R., Dias, R. and Almeida, M. (2018), ‘Local finance: economic principles, institutions and the Portuguese experience since 1987,’ Portuguese Public Finance Council. [Online], [Retrieved December 20, 2022], https://www.cfp.pt/uploads/publicacoes_ficheiros/cfp-2018-livro-financas-locais[1].pdf

- Bevan, G. and Hood, C. (2006) ‘What’s measured is what matters: targets and gaming in the English public health care system,’ Public Administration, 84(3), 517-538.

- Bolívar, M., Navarro-Galera, A., Muñoz L. and Lopez Subires, M. (2016) ‘Analysing forces to the financial contribution of local governments to sustainable development,’ Sustainability, 8(9),

- Caamano-Alegre, J., Lago-Penas, S., Reyes-Santias, F. and Santiago-Boubeta, A. (2013) ‘Budget transparency in local governments: an empirical analysis,’ Local Government Studies, 39(2), 182–207.

- Cabaleiro, R., Buch, E. and Vaamonde, A. (2013) ‘Developing a method to assessing the municipal financial health,’ The American Review of Public Administration, 43 (6), 729–751.

- Carvalho, J., Fernandes, M. and Camões, P. (2018) Financial yearbook of Portuguese municipalities – 2017, Order of Certified Accountants, Lisbon.

- Chen, S. (2023) ‘Performance feedback, blame avoidance, and data manipulation in the public sector: evidence from China’s official city air quality ranking,’ Public Management Review, 1-21.

- Christiaens, J., Reyniers B. and Rollé, C. (2010) ‘Impact of IPSAS on reforming governmental financial information systems: a comparative study,’ International Review of Administrative Sciences, 76(3), 537–554.

- Cohen, S. and Karatzimas, S. (2015) ‘Debate: Reforming Greek government accounting,’ Public Money & Management, 35(3), 178–180.

- Decree-Law 62/2013 of May 10. Establishes measures against delays in the payment of commercial transactions and transposes Directive 2011/7/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of 16 February 2011. The Portuguese Republic.

- Directive 2011/7/UE of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 2011 on combating late payment in commercial transactions. Official Journal of the European Union.

- Ehalaiye, D., Redmayne, N. and Laswad, F. (2020) ‘Does accounting information contribute to a better understanding of public assets management? The case of local government infrastructural assets,’ Public Money & Management, 41(2) 88-98.

- European Commission (2019) ‘Fiscal Sustainability Report 2018, vol. 1,’ European Commission. [Online], [Retrieved January 10, 2023], https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-01/ip094_en_vol_1.pdf

- European Parliament (2009) ‘Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on combating late payment in commercial transactions,’ European Parliament. [Online], [Retrieved February 1, 2023], https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52009PC0126&from=EN

- European Parliament (2018) ‘Directive 2011/7/EU on late payments in commercial transactions. European Implementation Assessment,’ European Parliament. [Online], [Retrieved January 10, 2023], https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2018/621842/EPRS_IDA(2018)621842_EN.pdf

- Gao, J., Chan, H. and Yang, K. (2021) ‘Gaming in Performance Management Reforms and Its Countermeasures: Symposium Introduction,’ Public Performance & Management Review 44(2). 243–249.

- International Monetary Fund. (2014) ‘International Monetary Fund Annual Report 2014: From stabilization to sustainable growth,’ International Monetary Fund. [Online], [Retrieved February 1, 2023], https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/AREB/Issues/2016/12/31/International-Monetary-Fund-Annual-Report-2014-Financial-Statements-41824

- Irwin, T. (2012) ‘Accounting Devices and Fiscal Illusions,’ International Monetary Fund. [Online], [Retrieved February 3, 2023], https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2012/sdn1202.pdf

- Kroll, A. and D. Vogel, D. (2021) ‘Why Public Employees Manipulate Performance Data: Prosocial Impact, Job Stress, and Red Tape,’ International Public Management Journal 24 (2), 164–182.

- Krueathep, W. (2014) ‘Bad luck or bad budgeting: an analysis of budgetary roles underpinning poor municipal fiscal conditions in Thailand,’ Public Budgeting & Finance, 34(3), 51-72.

- Law 73/2013 of September 3. Establishes the financial regime of local authorities and intermunicipal entities. The Portuguese Republic.

- Oulasvirta, L. (2014) ‘The reluctance of a developed country to choose international public sector accounting standards of the IFAC: A critical case study,’ Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25(3), 272–285.

- Pérez-López, G., Plata-Díaz, A., Zafra-Gómez, J. and López-Hernández, A. (2013) ‘Municipal debt in a context of economic crisis: analysis of the determinant factors and forms of management,’ Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Accounting Review 16(2), 83–93.

- Pierre, J. and Licht, J. (2021) ‘Collaborative Gaming: When Principals and Agents Agree to Game the System,’ Public administration 99 (4), 711–722.

- Resolution of the Ministers Council 34/2008 of February 22. The pay on time and hours programme. The Portuguese Republic.

- Santos, P. and Martinho, C. (2020) ‘Sustainability Assessment of Portuguese Local Governments (2009 to 2017): Accounting Information and Public Governance,’ Financial Determinants in Local Re-Election Rates: Emerging Research and Opportunities, 80-104.

- Santos, P., Martinho, C. and Albuquerque, F. (2021) ‘Is the Commercial Debt Default Ratio a reliable indicator of the Short-Term Financial Sustainability of Portuguese Local Governments?,’ Polish Journal of Management Studies, 24 (1): 322-336.

- Zafra-Gomez, J., Lopez-Hernandez, A. and Hernandez-Bastida, A. (2009) ‘Evaluating Financial Performance in Local Government: Maximizing the Benchmarking Value,’ International Review of Administrative Sciences, 75(1), 151–167.

- Zuccolotto, R. and Teixeira, M. (2014) ‘The causes of fiscal transparency: Evidence in the Brazilian states,’Revista Contabilidade & Finanças, 25(66), 242–254.