Introduction

Numerous audit failures have led regulators to challenge the independence of external auditors (Commission on Public Trust & Private Enterprise, 2003). One strategy for enhancing auditor independence has been suggested: requiring audit firm rotation by putting a cap on the number of years in a row one audit firm can audit a public corporation (U.S. Senate, 1976; AICPA, 1978; POB, 2001; SOX, 2002). According to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX, 2022), all audits of publicly traded companies must rotate the lead audit partner and audit review partner (or concurring reviewer) every five years.

Rotation of audit firms is not a novel idea. It has been put into practice in a number of nations even before SOX. Together with the SOX, however, several measures that included clauses addressing audit firm rotation were discussed as a way to improve auditor independence. Congress agreed more research was necessary to determine the potential implications of mandatory rotation on registered public accounting firms, but nothing was actually passed. Hence, in this study, we investigate whether an audit firm rotation policy has an impact on audit firm independence and audit quality.

DeAngelo (1981) claimed that audit quality acted as a probability for an auditor to detect and disclose irregularities in the client’s accounting system.. Watkins et al. (2004) assert that an audit is of high quality if the auditor can guarantee that the financial statements’ audit did not contain any substantial misstatements (i.e., no material misstatements) or fraud.

Both internal and external elements, with the internal ones coming from the auditor, affect the quality of the audit. Auditor rotation is one of the stated external factors that affect audit quality. Practitioners and academics have argued both for and against long-term auditor-client relationships over the years. Some people think that the duration of an audit firm’s relationship with the client puts public perceptions of auditor independence and audit quality in jeopardy. Thus, for a very long time it has been presented in the audit literature that the application of the mandatory rotation of the auditor significantly increases both the quality of the audit and the independence of the auditor.

In this context, there are both positive and negative arguments regarding mandatory auditor rotation, hence practitioners deduct that it may have both advantages or negative effects as regards audit quality (Deliu, 2013).

On the one hand, in the framework of the negative arguments that assume that the rotation of the auditor decreases the quality of the audit, it is assumed that the new auditor cannot perform an effective audit due to the primal lack of information about the client, which would lead to a decrease in the quality of the audit (Siregar et al., 2012; Junaidi et al., 2016; Chan & Hsu, 2017, Al-Nimer & Alqatan, 2018, Yalçin et al., 2019; Riyani et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022). Thus, the new auditor following the rotation of auditors is obliged to rely on the client’s estimates and statements, especially on the basis of the lack of important information such as the way the business operates, the accounting systems used, and the functionality of the internal control systems. All these elements lead to a decrease in the quality of the audit, especially in the first years of the audit (Kwak et al., 2018).

On the other hand, those who support the mandatory rotation of auditors consider that, in this setting, the probability of developing personal relationships with the audited client decreases, a fact that will increase the independence of the auditor and the quality of the audit (Ricken, 2016, Martani et al., 2021, Riyani et al., 2021). Chi (2011) discovered that the auditor rotation strategy utilized to lessen the effect of audit tenure might raise the caliber of the audits. The independence of an auditor is a recognized internal aspect that can affect audit quality. Auditor independence is thought to act as an intermediary variable between auditor rotation and audit quality. According to research, auditor rotation is required to increase independence and, ultimately, audit quality because of the low independence of auditors (Mohamed & Habib, 2013).

Our study is based on a sample of audit opinions of the companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange, for the period 2018-2021. The main scope of the study is to investigate the frequency of auditors’ rotations. From one point of view, the period 2018-2021 was chosen because this included a major global event (the COVID-19 pandemic), which could have had a significant impact on the financial statements and audit engagements of many companies (Deliu, 2020b). In addition, from another point of view, studying the frequency of auditors’ rotations in Romania can provide valuable insights into the state of the country’s accounting and auditing practices, and the financial health of Romanian companies, due to the fact that Romania is considered to be an emergent market (Deliu, 2019; Deliu, 2020a). Numerous businesses in such developing markets as Romania are affiliated with a worldwide group, and as a result, their consolidated financial statements are included in the financial statements published by the entire company. Therefore, it can be said that the Big 4/Non-Big 4 dichotomy is insufficient for the purposes of this study.

All of the Big 4 corporations and a few more businesses affiliated with international networks of accounting firms may be found in Romania on the audit market. There are also a lot of regional audit firms that are not a part of any global network. Joint audits are not yet required. Beginning in 2012, the regulation required practically all listed companies on the Bucharest Stock Exchange to adopt IFRS.

Previously, they were expected to report in accordance with Romanian regulations and only submit IFRS financial statements if they were presenting consolidated financial statements or for the purposes of investors. Grosanu & Berinde (2013) split Romanian auditors into three categories (Big 4, Non Big 4, and individuals), and discovered that Big Four auditors will see an ascending trend in terms of market share compared to local audit firms. The Big 4 firms only covered 18% of the entities in their sample for a number of significant companies from North-West Romania (Grosanu & Berinde, 2013). They also identified a few elements that they believe strongly influence why audited companies request the Big 4 auditors, including investors (domestic or foreign) and managers’ need for confidence.

Hence, some potential benefits of studying audit opinions in Romania include creating a framework of good practices for professional auditors (Figure 1), as regards:

- Enhanced audit quality. Audit rotation could reduce the risk of familiarity and self-review threats, and increase the objectivity and independence of auditors. This, in turn, could lead to better audit quality, which could benefit the investors and other stakeholders.

- Increased competition. Mandatory audit rotation could increase competition among audit firms, as it could give more opportunities for new firms to participate in the market. This could lead to better pricing, quality, and innovation.

- Improved transparency. Mandatory audit rotation could increase transparency, as it could give more opportunities for new auditors to review the financial statements and internal controls of the company. This could lead to more reliable and accurate financial reporting, which could benefit the investors and other stakeholders.

- Reduced risk of fraud. Mandatory audit rotation could reduce the risk of fraud, as it could prevent the long-term relationship between the auditors and the company management, which could lead to collusion and manipulation of financial statements.

- Alignment with international standards. Mandatory audit rotation could align Romania’s audit regulations with international standards, such as the EU Audit Reform, which requires mandatory audit rotation for public interest entities. This could enhance the country’s reputation and attract more foreign investment.

Figure 1. Framework of good practices for professional auditors

Source: Authors’ own projection

The paper is structured as follows: the Introduction sets the scene as regards the current market context that prompted the research theme, while the Literature Review presents the theoretical background in reference to studies enunciating the effects of audit firm rotation on auditor independence and audit quality. The Materials and Methods section, respectively the Results section will further assess findings, while the Discussions and Conclusions and Future Directions sections will deep-dive into comparing the results with existing research and drawing relevant conclusions and practical implications of the study.

Literature Review

In Romania, mandatory audit firm rotation was introduced in 2017 through the adoption of the Law No. 162/2017, which transposed the EU Audit Directive and Regulation into national law. According to this law, public-interest entities (PIEs) are required to rotate their audit firms every 10 years, with the possibility of extending the term to a maximum of 20 years if certain conditions are met.

The law defines PIEs as entities that are listed on a regulated market, credit institutions, insurance and reinsurance companies, investment firms, and other entities designated by national legislation.

The mandatory audit firm rotation requirements in Romania apply to both statutory and consolidated financial statements of PIEs. The law also requires that the newly appointed audit firm or partner should not have provided any non-audit services to the audited entity in the last 2 years preceding the appointment, with certain exceptions.

The introduction of mandatory audit firm rotation in Romania aimed to increase auditor independence and enhance audit quality by reducing the potential for familiarity threats that may arise from long-term auditor-client relationships. However, the effectiveness of mandatory audit firm rotation in achieving these objectives is a subject of ongoing debate and research in the academic literature.

Audit rotation refers to the practice of replacing the auditor of a company at regular intervals. It is intended to promote independence and objectivity in the audit process, as well as to improve the quality of the audit.

Research on the effect of audit rotation on the quality of audit has produced mixed results. Some studies have found that audit rotation leads to higher quality audits, as it promotes greater auditor skepticism and objectivity (Figure 2). Other studies have found no significant difference in audit quality between rotated and unrotated audits (DeAngelo, 1981; Siregar et al., 2012; Ewelt-Knauer et al., 2013; Hartono et al., 2016; Yang & Hong, 2016; Ricken, 2017; Choi et al., 2017; Kwak et al, 2018; Mohaisen et al. 2019; Yalcin et al., 2019; Mesly et al., 2020; Martani et al., 2021; Riyani et al., 2021; Filipović et al., 2021; Fauziyah et al., 2021; Saiewitz et al., 2021; Gramling & Stone, 2021; Lin et al., 2022).

Figure 2. Audit firm rotation and audit quality

Source: Ricken, 2017

One potential reason for these mixed results is that audit rotation may have different effects depending on the specific circumstances of the audit. For example, audit rotation may be more effective in promoting audit quality when the auditor has been in place for a long time or when there is a high level of familiarity between the auditor and the company (Garcia-Blandon & Argiles-Bosch, 2013; Paolone & Raucci, 2016; Adelowo & Oludayo, 2019, Nguyen & Mia, 2019; Filipović et al., 2021, Saiewitz et al., 2021, Duboisée de Ricquebourg et al., 2022).

Thus, it is clear that the practice of audit rotation has been the subject of debate and controversy, and opinions on its effectiveness and value vary among different stakeholders.

On the one hand, from the perspective of companies, audit rotation may be viewed as a burden and an unnecessary expense. It can be disruptive to the audit process and may require companies to invest significant resources in training new auditors and familiarizing them with the company’s operations and financial reporting. In addition, companies may have long standing relationships with their auditors and may prefer to continue working with them rather than going through the process of selecting and onboarding a new auditor (Siregar et al., 2012, Ricken, 2017, Lin et al., 2022).

On the other hand, audit rotation may be viewed as a way to promote greater independence and objectivity in the audit process, which can ultimately lead to more reliable financial reporting and greater confidence in the company’s financial statements. Some companies may also view audit rotation as an opportunity to bring in new perspectives and ideas from a fresh set of auditors (Hartono et al., 2016, Choi et al., 2017, Mohaisen et al., 2019, Yaşar et al., 2019, Saiewitz et al., 2021, Duboisée de Ricquebourg et al., 2022).

Thus, the decision to rotate auditors or not is a complex one that depends on a variety of factors, including the specific circumstances of the company and the views of its management, board of directors, and other stakeholders.

The most relevant pro arguments for the mandatory rotation of auditors are (Watkins et al., 2004, Siregar et al., 2012; Ewelt Knauer et al., 2013; Zhang & Xu, 2017; Yalcin et al., 2019; Martani et al., 2021; Duboisée et al., 2022):

Reducing the risk of audit firms developing relationships with their clients that could compromise their objectivity. Long-term relationships between audit firms and their clients can lead to familiarity and potential biases, which could affect the audit firm’s ability to audit the client’s financial statements objectively. By rotating auditors, the risk of these relationships developing is reduced, which can enhance the independence and objectivity of the audit.

- Promoting fresh perspectives and new approaches. New audit firms bring new perspectives and approaches to the audit process, which can lead to a more thorough and effective audit. This can be particularly beneficial in cases where the previous audit firm may have become complacent or may have missed important issues in previous audits.

- Providing opportunities for smaller firms. Auditor rotation can provide opportunities for smaller accounting firms to gain experience in auditing large publicly traded companies. This can help to promote competition in the audit industry and provide a level playing field for firms of all sizes.

- Enhancing transparency and public confidence. Auditor rotation can help to enhance transparency in the audit process and increase public confidence in the financial statements of publicly traded companies. This is especially important in cases where there have been concerns about the independence and objectivity of the audit process.

- Mandatory rotation does not allow for financial dependence on the client.

Thus, it is pointed out that the new auditor will be able to offer a high quality of services given the fact that he is neutral and applies professional skepticism within the audit mission.

On the contrary, among the arguments against the mandatory rotation of auditors we find (Chi, 2011; Ruankaew & Rattanasakorn, 2015; Lin et al, 2016; Junaidi et al., 2016; Kim et al, 2017; Deumes & Preston, 2018; Yalcin et al., 2019; Chen et al, 2021, Martani et al., 2021; Filipović et al., 2021; Fauziyah et al., 2021; Duboisée et al., 2022):

- Increased cost and disruption. Auditor rotation can be disruptive and costly, as the new audit firm must become familiar with the client’s business, accounting systems, and financial reporting processes. This can lead to increased audit fees and a higher burden on the client’s resources;

- Loss of expertise and continuity. The audit process can be complex and requires a deep understanding of the client’s business and industry. By rotating auditors, companies may lose the expertise and continuity that come with a long-term relationship with a single audit firm;

- Risk of inadequate training and experience. While auditor rotation can provide opportunities for smaller firms to gain experience in auditing large, publicly traded companies, it can also result in inexperienced auditors being assigned to audit engagements for which they may not be adequately trained or experienced. This can increase the risk of errors or omissions in the audit process;

- Potential for less independence. In some cases, auditor rotation may not necessarily enhance the independence of the audit, as the new audit firm may be subject to similar pressures and incentives as the previous firm. For example, the new audit firm may have an incentive to maintain a long-term relationship with the client in order to secure future audit engagements.

Choi et al. (2017) tried to investigate the effect of audit firm rotation and big 4 audit on the audit quality in South Korea and they found that the audit quality related to the mandatory rotation is higher than voluntary, besides they found that switching to Big 4 audits has a significant positive effect on the audit quality.

Concurrently, Mohaisen et al. (2019) analyzed the relationship between auditor rotation and audit quality; the findings of this study insure that the firms that rotate their auditors mandatorily have higher audit quality than that of voluntarily rotating auditors. In addition, they agree with Choi et al. (2017) that switching to Big 4 audits has a significant positive effect on the audit quality.

On the same note, Mesly et al. (2020) analyzed the impact of mandatory audit firm rotation on audit quality in Europe. Some of the key findings of the paper are as follows:

- Mandatory audit firm rotation is associated with a significant improvement in audit quality. The study finds that companies subject to mandatory rotation had higher audit quality scores than those that were not subject to rotation.

- The positive effect of mandatory rotation on audit quality is stronger for companies with higher levels of financial reporting complexity.

- The study finds that mandatory rotation does not lead to a significant increase in audit fees.

- The positive effect of mandatory rotation on audit quality is stronger in countries with weaker legal systems and lower levels of auditor independence.

- The study also finds that mandatory rotation can lead to some negative consequences, such as a decline in auditor expertise and an increase in audit failures in the short term. However, these negative effects tend to dissipate over time as auditors gain experience with their new clients.

The effects of audit partner rotation on audit quality were thoroughly investigated by Saiewitz et al. (2021), who analyzed data from the post-Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) period in the United States. They found that audit partner rotation can have a positive effect on audit quality, particularly in cases where the outgoing partner had a close relationship with the audited company. This leads to the assumption that the benefits of partner rotation were greater for companies with lower litigation risk and higher partner specialization.

Hence, there is clear evidence that audit partner rotation can be an effective mechanism for enhancing audit quality.

In the same vein, Filipović et al. (2021) aimed to study the different efforts related to analyzing the effects of mandatory audit firm rotation from the perspective of academics in South Africa and they found that audit firm rotation has a great positive effect on the auditor independence and hence, the audit quality.

Along the same lines, Ricquebourg et al. (2021) examined the effects of auditor rotations on key audit matters (KAMs) in South African audits. They collected data from 2014 to 2019, a period in which the mandatory audit firm rotation policy was implemented in South Africa. The authors found that auditor rotations have a significant impact on the number and type of KAMs reported by auditors. Specifically, they found that auditor rotations result in a decrease in the number of KAMs reported, as well as a shift in the type of KAMs reported. The authors suggest that this is due to a lack of familiarity with the client’s business and processes, and a resulting lack of confidence in identifying and reporting KAMs. The study provides important insights into the effects of auditor rotations on audit quality and reporting, particularly in the context of mandatory rotation policies.

Finally, we conclude that recent studies still have controversial results as well as other prior literature. So, we can ensure that the direction of the relationship between audit rotation and audit quality is not clear yet. Thus, our research embodied this relationship for the firms listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange.

Materials and Methods

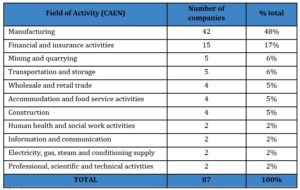

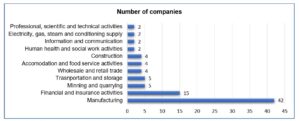

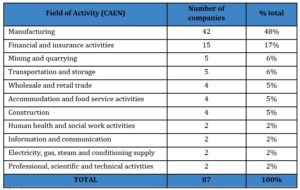

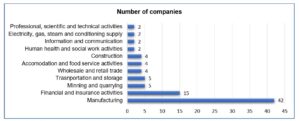

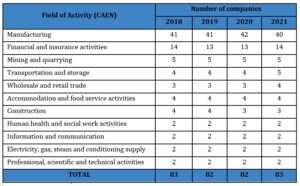

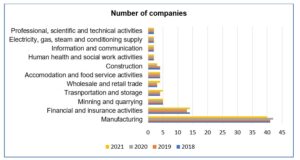

We first identified the statistical population of the sample represented by the companies listed on the stock market of the Bucharest Stock Exchange, in the period 2018-2021. Our sample consists of 87 companies that carry on activities as regards Manufacturing Financial and insurance activities, Mining and quarrying, Transportation and storage, Wholesale and retail trade, Accommodation and food service activities, Construction, Human health and social work activities, Information and communication, Electricity, gas, steam and conditioning supply, Professional, scientific and technical activities. Thus, the structure by fields of activity of the sample of companies is presented below (Table 1; Figure 3).

Table 1. Companies’ structures by fields of activity

Source: Authors’ own projection

Source: Authors’ own projection

Figure 3. Companies’ structures by fields of activity

Source: Authors’ own projection

Following the analysis of the structure of the companies by fields of activity, the significant share of the companies in the manufacturing industry and of the financial and insurance companies can be observed, representing a percentage of 65% of the total analyzed sample. For a more detailed analysis of the companies by fields of activity, their structuring was performed for each verified year, as presented in Table 1 and Figure 3.

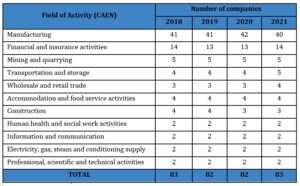

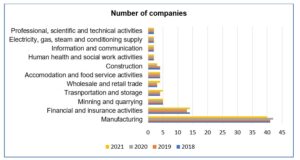

Table 2: Annual structure of companies by fields of activity

Source: Authors’ own projection

Source: Authors’ own projection

Figure 4: Annual structure of companies by fields of activity

Source: Authors’ own projection

Over the whole period analyzed, the companies in the manufacturing industry represented the largest share of the sample, the annual structure being relatively constant, as presented in Table 2 and Figure 4. Thus, we considered this field of activity as the most relevant to analyze in order to formulate a conclusion of the study.

Even if there were certain fluctuations of the companies listed on the stock market of the Bucharest Stock Exchange, we can say that they are minor, being made mainly based on the opening of the insolvency procedure.

Results

The auditor’s ability to remain impartial and independent is also dependent on the frequency of his rotation, which has a direct bearing on the caliber of the financial audit engagement and, implicitly, the audit opinion (Garcia-Blandon & Argiles-Bosch, 2013).

The concept of auditor rotation takes into account the maximum number of years that the same auditor can provide the required financial auditing of financial statements for a specific client. Rotation may be required or optional. Regarding the financial auditor’s mandatory rotation, its introduction is primarily intended to lower the risk of non-compliant audits, boost auditor independence, and raise investor confidence in the issued audit opinion and the data from the financial statements.

Taking into account the controversies identified in the literature related to the rotation of auditors, I considered it appropriate to study the rotation of auditors for companies listed on the stock market of the Bucharest Stock Exchange, in 2018-2021, and the total number of observations was 330 .

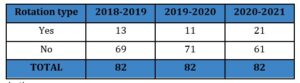

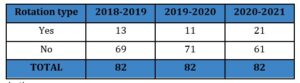

To begin with, we checked whether there were auditors’ rotations for the three financial years between the period 2018 and 2021, the results being presented in Table 3.

Table 3. The number of companies that changed the auditor in the period 2018-2021

Source: Authors’ own projection

Source: Authors’ own projection

Regarding the existence of auditors’ rotations, we identified a rotation in a percentage of 16% in the period 2018-2019, 13% in the period 2019-2020, respectively a percentage of 26% in the period 2020-2021.

Another important assumption was the rotation of auditors in relation to audit firms. Thus, we established the 4 types of auditor rotations as follows:

- Big Four to Big Four

- Big Four to Non Big Four

- Non Big Four to Big Four

- Non Big Four to Non Big Four

Thus, following the analysis of the information collected, we identified the following frequency of auditors’ rotations for each type of rotation, this being presented in Table 4.

Table 4. The correlation between auditors’ rotations and types of audit companies

Source: Authors’ own projection

Source: Authors’ own projection

Based on the results obtained, we can identify the fact that most rotations were of the type of rotation of a Non Big Four company with another also of the type Non Big Four, the largest rotation taking place in the period 2020-2021.

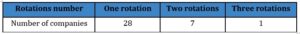

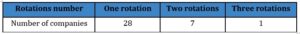

Regarding the number of auditors’ rotations, performed during the three analyzed periods, we considered it opportune to present the results in Table 5.

Table 5. Frequency of auditors’ rotation in the period 2018-2021

Source: Authors’ own projection

Based on the available data, it appears that there was a significant level of auditor rotation among companies during the period of 2018-2021. Out of the total of 36 companies examined, 28 had one auditor rotation, 7 had two auditor rotations, and 1 had three auditor rotations. This suggests that many companies are taking steps to rotate their auditors on a regular basis, which can help to ensure greater transparency and accuracy in financial reporting.

Discussion

The purpose of our research was to analyze the audit opinions of companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange from 2018 to 2021, with a specific focus on the frequency of auditor rotation. By examining these data, we aimed to gain insights into how often companies switch auditors, which can have significant implications for the quality of financial reporting and overall business performance.

To ensure that our findings are relevant and up-to-date, we chose to study the period between 2018 and 2021. This time frame is notable because it includes the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a profound impact on the global economy and business operations across many industries (Deliu, 2020b). As a result, we believe that the pandemic may have affected the financial statements and audit engagements of the companies we studied, and our analysis will provide valuable insights into the potential impact of this unprecedented event on audit practices and procedures. Overall, our study will contribute to the ongoing conversation around audit quality and best practices for financial reporting in today’s rapidly changing business landscape.

In addition to investigating the frequency of auditor rotations, our study also aimed to identify any trends or patterns that may emerge from our analysis of the audit opinions. Furthermore, we explored whether certain industries or sectors are more likely to experience auditor rotation than others, and whether there are any correlations between auditor rotation and financial performance or other business metrics. By taking a comprehensive and data-driven approach to our research, we hope to shed light on the complex and evolving landscape of audit practices and their impact on corporate governance and financial reporting.

Looking at the frequency of auditor rotations in Romania can provide us with valuable insights into the state of accounting and auditing practices in the country. Romania is considered to be an emergent market, which means that the country’s economy is in the process of rapid development and growth (Deliu, 2019; Deliu, 2020a). As such, it is important to understand the financial health of Romanian companies and the quality of their financial reporting. By analyzing the frequency of auditor rotations, we can gain a better understanding of the level of scrutiny and oversight applied to financial reporting practices in Romania. This can help identify areas where improvements can be made in order to increase transparency, accountability, and overall confidence in the financial markets.

For example, if auditor changes are driven primarily by the expiration of contracts or changes in leadership, it may suggest stability and continuity in the companies’ operations (Mohamed & Habib, 2013; Gray & Wang, 2014; Eldeen & Abdel-Maksoud, 2018; Krishnan & Krishnan, 2018; Mavhanzi & Bennie, 2019). However, if auditor changes are driven by perceived issues with audit quality or other concerns, it may signal potential problems with the financial health of the company (Zhang & Xu, 2017; Al-Nimer & Alqatan, 2018; Adelowo & Oludayo, 2019). These insights can be particularly valuable for investors, regulators, and other stakeholders who are interested in understanding the state of the Romanian economy and financial markets.

By taking a comprehensive and data-driven approach to our analysis, we looked to gain a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities facing Romanian businesses and financial markets, and identify potential areas for improvement and growth.

This study began by identifying the statistical population of the sample, which consists of companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange between 2018 and 2021. The sample includes 87 companies that operate in various industries, including Manufacturing Financial and insurance activities, Mining and quarrying, Transportation and storage, Wholesale and retail trade, Accommodation and food service activities, Construction, Human health and social work activities, Information and communication, Electricity, gas, steam, and conditioning supply, Professional, scientific and technical activities.

By analyzing the structure of the companies in our sample by field of activity, we discovered that the manufacturing industry and financial and insurance companies represent a significant percentage of the total sample, accounting for 65%. This finding is particularly interesting, as the manufacturing industry is typically seen as a key driver of economic growth, while financial and insurance activities are critical components of a well-functioning financial system.

This approach allows us to identify any differences in the frequency of auditor rotations across industries and to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on different sectors. By taking a comprehensive and diverse approach to our analysis, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of the factors driving auditor rotations in Romania and their potential implications for the country’s financial markets and overall economic performance.

We found that there were significant changes in the percentage of rotations over the three-year period from 2018 to 2021. In 2018-2019, we identified a rotation in 16% of the companies in our sample. This percentage decreased to 13% in the following year, which suggests that companies may have been more satisfied with their auditors or that contracts were renewed.

However, in 2020-2021, we observed a sharp increase in the percentage of auditors’ rotations to 26%, which could be attributed to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on businesses and their financial reporting practices. The pandemic has caused significant disruptions to the global economy, and many companies have been forced to adapt their operations and financial reporting practices in response (Deliu, 2020b). This may have led to increased scrutiny from auditors, resulting in more frequent rotations.

The increase in the percentage of rotations in 2020-2021 is particularly noteworthy, as it represents a significant change from the previous year and may have important implications for the financial health of Romanian companies. Frequent changes in auditors can signal issues with audit quality or financial reporting practices, which can in turn affect the trust and confidence of investors and other stakeholders in the company (Ruankaew & Rattanasakorn, 2015; Kim et al, 2017; Kwak et al, 2018; Mavhanzi & Bennie, 2019). This underscores the importance of closely monitoring auditor rotations and understanding the factors driving them in order to identify potential issues and improve financial reporting practices.

Another important aspect that we examined in our study was the rotation of auditors in relation to audit firms. To investigate this issue, we established four different types of auditor rotations based on whether the company switched from a Big Four audit firm to another Big Four firm, from a Big Four firm to a non-Big Four firm, from a non-Big Four firm to a Big Four firm, or from a non-Big Four firm to another non-Big Four firm.

This approach allowed us to identify any trends or patterns in auditor rotations and to evaluate the potential impact of these rotations on the quality of financial reporting. For example, if companies frequently switched from a Big Four firm to a non-Big Four firm, it could suggest that they were looking for cheaper audit services or that they were dissatisfied with the quality of service provided by the Big Four firms (Huang & Houghton, 2013; Paolone & Raucci, 2016; Yang & Hong, 2016). On the other hand, if companies primarily switched from non-Big Four firms to Big Four firms, it could indicate that they were seeking higher-quality audit services or that they perceived the Big Four firms as having greater expertise or reputation (Gray & Wang, 2014; Chan & Hsu, 2017; Krishnan & Krishnan, 2018; Nguyen & Mia, 2019).

By analyzing these different types of auditor rotations, we were able to gain a deeper understanding of the factors driving these changes and their potential implications for the financial health of Romanian companies. This information is valuable for investors, regulators, and other stakeholders, as it can help to identify potential risks and opportunities in the market and inform decision-making processes related to financial reporting and auditing practices.

Our study revealed interesting insights into the types of auditor rotations that occurred in the sample of Romanian companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange between 2018 and 2021. Based on our analysis, we found that the majority of auditor rotations were of the type where a non-Big Four audit firm was replaced by another non-Big Four firm.

This finding suggests that many companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange may prioritize cost over perceived quality when choosing their auditor. Non-Big Four audit firms may offer more affordable services than their Big Four counterparts, which could be a major factor in their selection. However, this approach may also carry certain risks, as non-Big Four firms may not have the same level of expertise or reputation as their larger competitors.

The analysis conducted on the auditors’ rotations provides valuable insights into the auditing practices of the 87 companies that were examined. The findings suggest that these companies have varied approaches when it comes to changing their auditors.

Out of the 87 companies, 28 had only 1 audit rotation during the analyzed periods. This indicates that the majority of these companies prefer to maintain a long-term relationship with their auditor, possibly due to their trust in their auditor’s work or the auditor’s familiarity with the company’s operations. On the other hand, 7 companies had 2 audit rotations during the analyzed periods, suggesting that these companies prioritize a fresh perspective from a new auditor or may have experienced issues with their previous auditor that warranted a change. Interestingly, only 1 company had a single audit rotation during the analyzed period. This finding raises questions about why this company changed its auditor, and whether there were any significant issues with the previous auditor that led to the change.

It is worth noting that auditors’ rotations are essential in maintaining the integrity of financial reporting and reducing the risks of fraud (Huang & Houghton, 2013; Eldeen & Abdel-Maksoud., 2018; Gramling & Stone, 2021). Therefore, it is vital for companies to have effective and efficient mechanisms in place to ensure that their auditors are rotated periodically (Lin et al, 2016; Deumes & Preston, 2018; Chen et al, 2021).

Conclusions and Future Research Directions

In this study, we examined the impact of mandatory audit partner rotation on audit quality and found evidence suggesting that such requirements can improve audit quality. Our results indicate that rotating audit partners enhances auditors’ independence and reduces the risk of client-specific knowledge spillovers.

Overall, our findings have important implications for audit practice and policy. By providing evidence that mandatory audit partner rotation can enhance audit quality, our study supports the continued use of such requirements in regulatory frameworks. However, our results also suggest that policymakers should carefully consider the potential trade-offs between improved audit quality and other factors, such as audit costs and auditor expertise, when designing and implementing mandatory audit partner rotation requirements.

It is difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of auditor rotation as a means of enhancing the independence and objectivity of the audit process. While auditor rotation can bring fresh perspectives and new approaches to the audit process, it can also be disruptive and costly, and may not necessarily enhance the independence and objectivity of the audit.

Ultimately, the decision to implement auditor rotation should be based on a careful consideration of the specific circumstances of the company and the audit process, as well as the relevant laws, regulations, and professional standards. In some cases, auditor rotation may be required by law or regulation, while in other cases it may be a matter of corporate policy or best practice. It is important for companies to carefully evaluate the pros and cons of auditor rotation and to consider any potential impact on the quality, cost, and efficiency of the audit process.

Hence, some of the main conclusions are:

- Mandatory audit firm rotation has a positive impact on audit quality. The study finds that companies subject to mandatory rotation had higher audit quality scores than those that were not subject to rotation;

- The positive effect of mandatory rotation on audit quality is stronger for companies with higher levels of financial reporting complexity. This suggests that mandatory rotation can be particularly effective in improving the quality of audits for companies that face greater reporting challenges;

- The positive effect of mandatory rotation on audit quality is stronger in countries with weaker legal systems and lower levels of auditor independence. This suggests that mandatory rotation policies can be especially effective in improving audit quality in countries with weaker regulatory environments;

- Mandatory rotation can lead to some negative consequences, such as a decline in auditor expertise and an increase in audit failures in the short term. However, these negative effects tend to dissipate over time as auditors gain experience with their new clients.

The literature suggests that audit firm rotation can help to address familiarity threat and increase auditor independence, which can in turn lead to improved audit quality. The potential benefits of rotation include: improving audit quality, increasing competition, reducing familiarity threat, and enhancing the perceived independence of auditors.

However, there are also potential costs associated with audit firm rotation, including increased costs and reduced efficiency due to the learning curve associated with a new client, reduced auditor expertise, and potential disruption to client relationships. As such, the implementation of audit firm rotation policies needs to be carefully balanced to ensure that the benefits of rotation outweigh the costs.

The literature also suggests that the optimal length of the rotation period may depend on a number of factors, such as the size and complexity of the client, the regulatory environment, and the competitive landscape. Further research is needed to better understand the potential costs and benefits of audit firm rotation, and to develop more precise and nuanced policy recommendations.

Overall, while mandatory audit firm rotation may not be a silver bullet for improving audit quality, it remains an important policy tool for regulators to consider in their efforts to improve the reliability of financial reporting and enhance investor confidence in the financial markets.

The four directions of the rotation are from Big Four to Big Four, from Big Four to Non Big Four, from Non Big Four to Big Four, and from Non Big Four to Non Big Four. Investors can utilize this information to assess the caliber of the auditing mission as well as the caliber of the reported data. In addition, they can use information about the auditor’s rotation to assess the auditor’s objectivity, independence, and competence. To this extent, we can conclude that the emergence of the rotation results from the executive’s desire to “purchase” a certain type of auditing opinion, choosing a certain auditor.

The limits of the study are mainly determined by the small volume of the analyzed sample, by including in the analysis only the Romanian companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange in the period 2018-2021. In future studies, the aim is to identify the impact of auditors’ rotation on the opinions to be brought at both a larger national and international level. We also acknowledge the potential for other unmeasured factors to affect our results and the possibility that our findings may not apply to all types of audits or audit settings. In this context, future research should investigate the effects of mandatory audit partner rotation on other aspects of audit quality, such as audit efficiency and effectiveness, and consider the potential costs and benefits of implementing such requirements.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused disruptions in supply chains, led to reduced demand for certain products and services, and caused a significant economic downturn. As a result, companies have had to adjust their financial reporting practices and engage with their auditors in new ways. In this context, due to the sensitive socio-economic context, as businesses have been forced to adapt to new working conditions and, ultimately, challenges as regards financial reporting, auditor rotations were impacted as well (Deliu, 2013; Deliu, 2020b).

One of the primary effects of the pandemic on auditor rotations has been an increase in remote auditing. Many auditors have had to conduct audits remotely due to travel restrictions and social distancing guidelines. This has required auditors to use new technologies and communication tools to carry out their work effectively.

Another impact of the pandemic on auditor rotations has been the increased focus on risk management. With the economic uncertainty brought on by the pandemic, auditors have had to pay closer attention to the risks associated with their clients’ financial statements. This has resulted in a greater emphasis on fraud detection and prevention, as well as more thorough assessments of internal controls.

The increased use of remote auditing and the heightened focus on risk management are just two examples of how the pandemic has changed the way that auditors operate. As businesses continue to adapt to the new normal, auditors will need to remain vigilant and flexible in order to meet the changing needs of their clients.

References

- Adelowo, GE. and Oludayo, OS. (2019), ‘The Effect of Auditor Tenure and Auditor Change on Audit Quality of Listed Companies in Nigeria’, Journal of Accounting and Auditing: Research & Practice 2019, 1-10.

- Al-Nimer, M. and Alqatan, A. (2018), ‘Audit Firm Tenure, Non-Audit Services, and Audit Quality: Evidence from Jordan’, Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 8(4), 461-480.

- American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (1978). Code of Professional Conduct.

- Chan, KH. and Hsu, AW. (2017), ‘Why Do Companies Switch Auditors? A Comprehensive Literature Review’, Journal of Accounting Literature 38, 1-29.

- Chen, YC., Hsu, AW. and Lee, YW. (2021), ‘Auditor tenure and audit quality: Evidence from mandatory auditor rotation’, Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics 17(2), 100271.

- Chi, W. (2011), ‘The Effect of the Enron-Andersen Affair on Audit Pricing’, SSRN Electronic Journal 886.

- Choi, JS., Lim, HJ. and Mali, D. (2017), ‘Mandatory audit firm rotation and Big4 effect on audit quality: Evidence from South Korea’, Asian Academy of Management Journal of Accounting and Finance 13 (1), 40.

- Commission on Public Trust & Private Enterprise. (2003). Report of the National Commission on Fraudulent Financial Reporting.

- DeAngelo, LE. (1981), ‘Auditor size and audit fees’, Journal of Accounting and Economics 3(5), 183–199.

- Deliu, D. (2013), ‘The Responsibilities and Limited Liability of the Financial Auditor in a Sensitive Socio-Economic Context’, PhD thesis, West University of Timişoara, Timişoara, Romania.

- Deliu, D. (2019), ‘Brief Critical Analysis of the Main Corporate Governance Traits within Romanian Banks Listed on Bucharest Stock Exchange’, In Proceedings of the 34th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA) Conference.

- Deliu, D. (2020a), ‘Key Corporate Governance Features within Romanian Banks Listed on Bucharest Stock Exchange: A Thorough Scrutiny and Assessment’, Journal of Eastern Europe Research in Business and Economics 271202(10).

- Deliu, D. (2020b), ‘The Intertwining between Corporate Governance and Knowledge Management in the Time of Covid-19–A Framework’, Journal of Emerging Trends in Marketing and Management 1(1), 93-110.

- Deumes, R. and Preston, A. (2018), ‘Auditor tenure, audit quality and audit fees: Evidence from the UK’, British Accounting Review 50(5), 539-557.

- Duboisée de Ricquebourg, AD. and Maroun, W. (2022), ‘How do auditor rotations affect key audit matters? Archival evidence from South African audits’, The British Accounting Review.

- Eldeen, GS. and Abdel-Maksoud, A. (2018), ‘The Determinants of Auditor Changes in the UK: Evidence from FTSE 350 Firms’, International Journal of Auditing 22(2), 288-301.

- Ewelt-Knauer, C., Gold, A. and Pott, C. (2013), ‘Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation: A Review of Stakeholder Perspectives and Prior Research’, Accounting in Europe 10 (1), 27-41.

- Fauziyah, N. and Darmayanti, N. (2021), ‘The Influence of Audit Costs, Audit Engagement and Audit Rotation on Audit Quality’, Journal of Auditing, Finance, and Forensic Accounting 9 (1), 34-43.

- Filipović, I., Šušak, T. and Lijić, A. (2021), ‘Effect of Auditor Rotation on Relationship Between Financial Manipulation and Auditor’s Opinion’, A Systems View across Technology & Economics 12 (1), 96-108.

- Garcia-Blandon, J. and Argiles-Bosch, JM. (2013), ‘Auditor independence: The effect of the provision of non-audit services’, Revista de Contabilidad 16(1), 69-87.

- Gramling, AA. and Stone, DN. (2021), ‘Auditor rotation and audit quality: An experimental investigation’, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 36(4), 710-729.

- Gray, CJ. and Wang, SHL. (2014), ‘Corporate Governance and Auditor Choice in UK SMEs’, Accounting and Business Research 44(3), 261-288.

- Grosanu, A. and Berinde, M. (2013), ‘Auditor independence, regulation and fraud prevention’, Procedia Economics and Finance 6, 498-508.

- Hartono, J., Junaidi, Suwardi, E., Miharjo, S. and Hartadi, B. (2016), ‘Does Auditor Rotation Increase Auditor Independence?’, Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business 18 (3), 315.

- Huang, X. and Houghton, KA. (2013), ‘Do Clients Switch Between Big 4 and Non-Big 4 Auditors to Manage Earnings? Evidence from the UK’, Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 40(7-8), 901-929.

- Kim, JJ., Chang, YK. and Lee, K. (2017), ‘Auditor Turnover, Audit Quality, and Market Perception: Evidence from the Korean Stock Market’, International Journal of Auditing 21(2), 154-167.

- Krishnan, GV. and Krishnan, J. (2018), ‘The Relation between Auditors’ Fees for Nonaudit Services and Earnings Management’, The Accounting Review 71(4), 721-735.

- Kwak, SW. and Tan, HT. (2018), ‘The Effect of Auditor Tenure and Auditor Switching on Earnings Quality: Evidence from Korea’, Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics 25(1-2), 28-47.

- Lin, TW., Chen, S. and Chen, YH. (2016), ‘The effect of mandatory auditor rotation on audit quality: Evidence from Taiwan’, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 35(4), 417-435.

- Lin, HL. and Yen, A. (2022), ‘Auditor rotation, key audit matter disclosures, and financial reporting quality’, Advances in Accounting 57 (4), 213-238.

- Martani, D., Rahmah, NA. and Anggraita, V. (2021), ‘Impact of audit tenure and audit rotation on the audit quality: Big 4 vs non big 4’, Cogent Economics & Finance 9 (1), 1901395.

- Mavhanzi, NW. and Bennie, S. (2019), ‘The Effect of Audit Firm Tenure and Firm Size on Audit Quality: Evidence from South Africa’, Meditari Accountancy Research 27(2), 282-306.

- Mesly, O., Jeanjean, T. and Mnif, A. (2020), ‘Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation and Audit Quality: Evidence from Europe’, Journal of Accounting Research 58(3), 571-602.

- Mohaisen, HA., Ali, KS. and Ibrahem, AT. (2019), ‘The Effect of Audit Rotation on the Audit Quality: Empirical Study on Iraq’, Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 14 (13), 4553-4558.

- Mohamed, DM., Habib, MH. (2013), ‘Auditor independence, audit quality and the mandatory auditor rotation in Egypt’, Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues

- Nguyen, TH. and Mia, L. (2019), ‘Auditor switching and the Big 4 premium in audit fees: Evidence from Australia’, Pacific Accounting Review 31(4), 530-548.

- Paolone, F. and Raucci, D. (2016), ‘Audit Market Structure and Auditor Switching: Evidence from Italy’, International Journal of Auditing 20(1), 1-13.

- Public Oversight Board. (2001). Report and Recommendations of the Panel on Audit Effectiveness.

- Ricken, S. (2016), ‘Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation in a Big 4 audit firm’, Master Thesis Economics, Specialization: Accounting & Control, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

- Riyani, FF., Setyawati, NW. and Husadha, C. (2021), ‘The Effect of Audit Tenure, Audit Rotation and Head Reputation on Audit Quality’, Journal of Research in Business, Economics, and Education 3 (3), 1832-1842.

- Ruankaew, T. and Rattanasakorn, T. (2015), ‘The Effects of Audit Quality on Corporate Performance: Evidence from Thailand’, Journal of Applied Accounting Research 16(3), 342-357.

- Saiewitz, A., Owens, EL. and Schipper, I. (2021), ‘Audit partner rotation and audit quality’, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 36(1), 26-44.

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX), Pub. L. No. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745 (2002).

- Siregar, SV., Amarullah, F. and Wibowo, A. (2012), ‘Audit Tenure, Auditor Rotation, and Audit Quality: The Case of Indonesia’, Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 5 (1), 55-74.

- S. Senate (1976). Legislative History of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977.

- Watkins, AL., Hillison, W. and Morecroft, SE. (2004), ‘Audit Quality : A Synthesis Of Theory And Empirical Evidence’, Journal of Accounting Literature 23(4), 19–153.

- Yalçin, N. and Yaşar, A. (2019), ‘The effect of mandatory audit firm rotation on audit quality’, International Journal Of Eurasia Social Sciences 10 (37), 692-708.

- Yang, SR. and Hong, SJ. (2016), ‘Factors Affecting Auditor Switching in the Korean Market: A Comparison between Big Four and Non-Big Four Firms’, Journal of Applied Accounting Research 17(1), 24-45.

- Zhang, J. and Xu, N. (2017), ‘The Consequences of Auditor Switching: Evidence from the Small Audit Firm Market’, Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 44(9-10), 1364-1397.