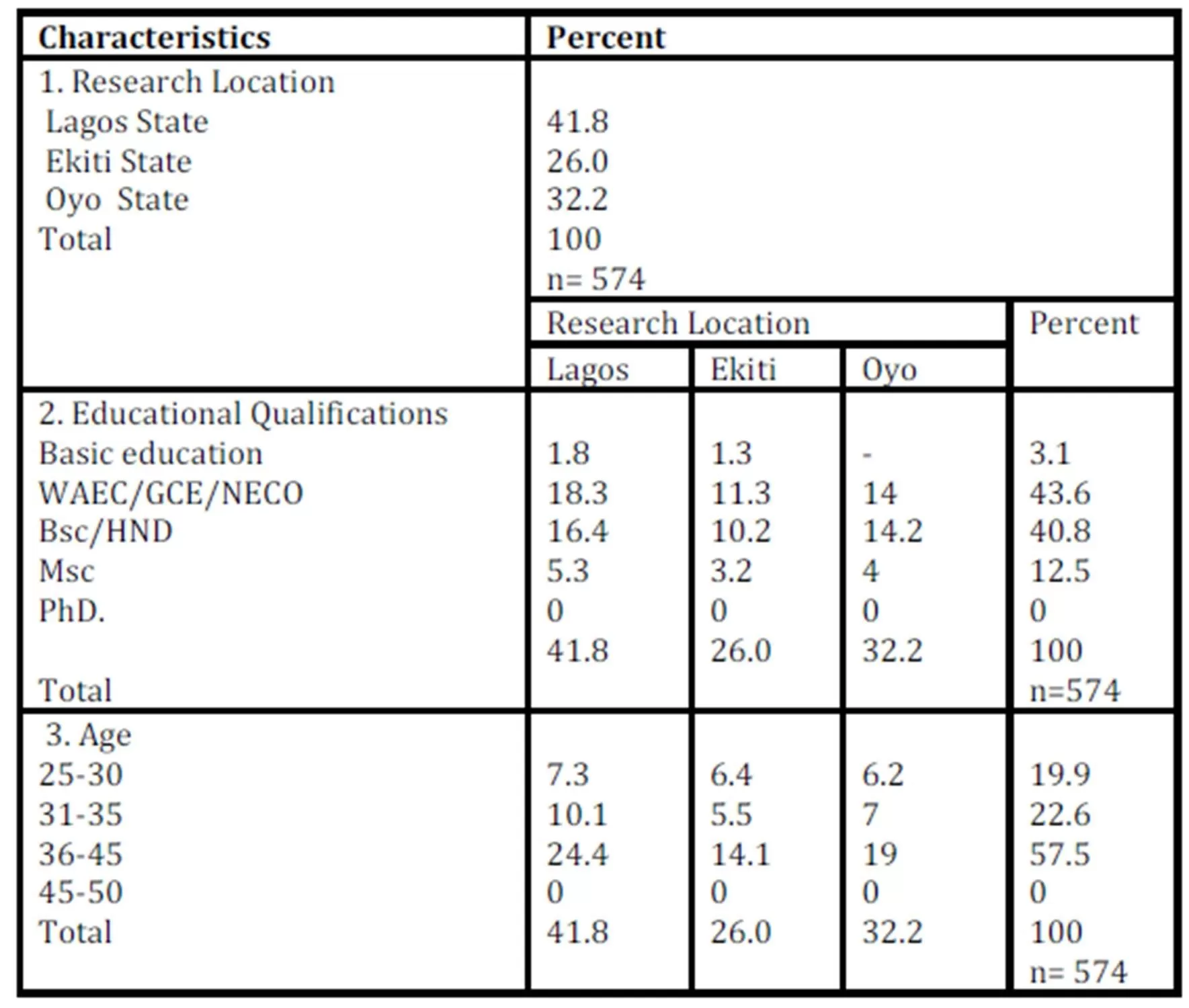

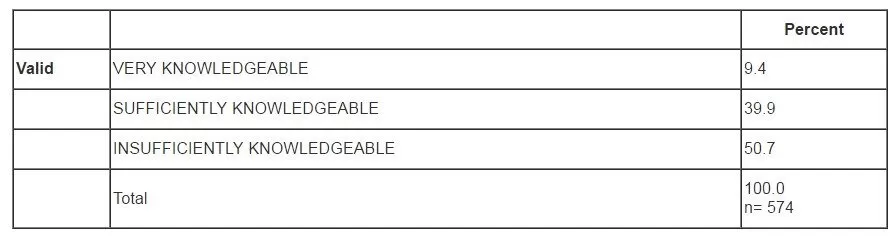

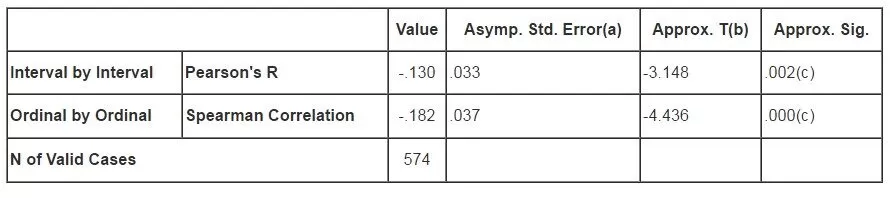

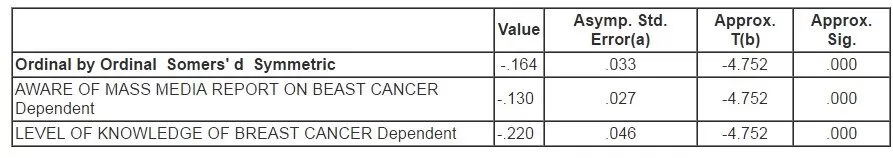

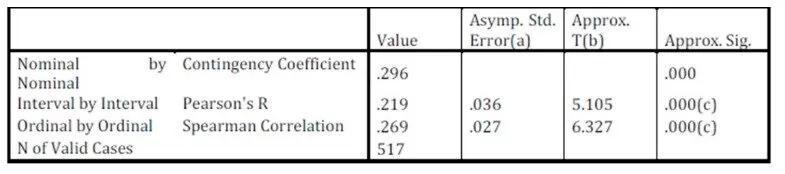

The presentation and analysis of the data have brought a lot of issues to the fore. Some of these issues support as well as mark a departure from existing literature and theory in health communication studies. The first hypothesis which stated, there is no significant relationship between exposure to media information and the level of knowledge of breast cancer was rejected. Correlation analysis on Table 4 a and b revealed there was a relationship between variables, but the relationship was a weak one. In other words, the results from the Correlation tests at the 5% alpha level of significance were significant enough to validate or support the hypothesis. Table 4b helps to determine the strength and direction between variables i.e. the approximate significance value has 0.00 in its column; one can infer there was a relationship between the variables. In addition, the value statistics helps to determine the strength or the direction of the relationship, it can range from -1 to 1 i.e. negative values indicate a negative relationship, and positive values indicate a positive relationship. From table 4b, the relationship between variables is a weak one.

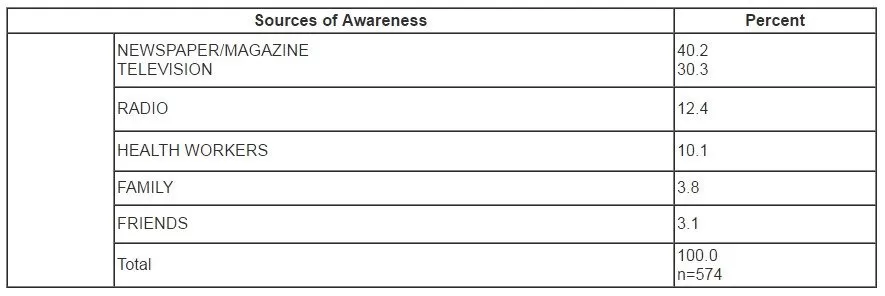

This study confirmed that mass media channels constitute the primary sources of information and could significantly influence breast cancer knowledge. In other words, the mass media serve as veritable channels for breast cancer care among women. Also, the fact that mass media are important in promoting health messages cannot be ignored because they serve as primary carriers of health communication messages in the Nigerian society. It is not unlikely to say that mass media are indispensable tools of health communication for breast awareness campaigns.

Against the backdrop of the agenda setting theory, mass media experts could effectively frame issues of breast cancer by informing people of the need to prevent themselves from the disease. Also, the diffusion of innovation theory places communication at the centre of the process of innovation and change. Communication is conceived of as the process through which information is exchanged, meaning is constructed, and ambiguity is resolved (Rogers & Kincaid, 1981). According to this perspective, different communication channels make them differentially suited to satisfying individual needs for information, validation and uncertainty reduction. This theory also stipulates that media outlets are essential health communication tools used to create awareness.

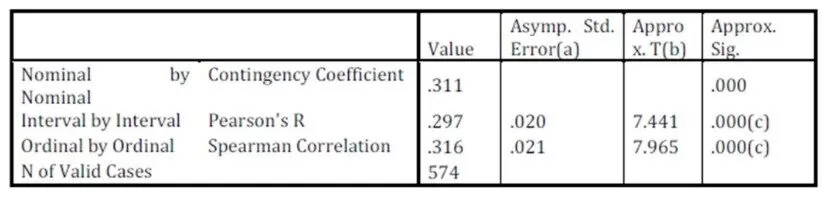

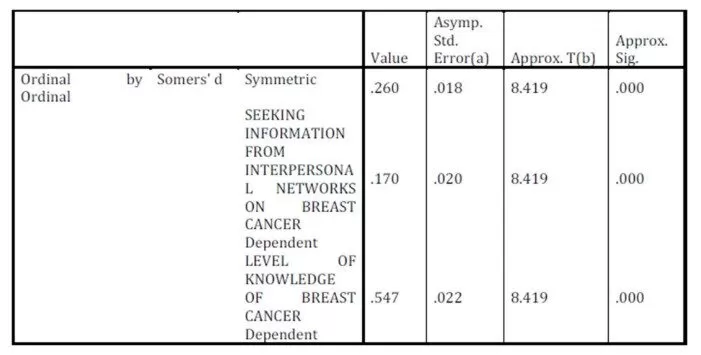

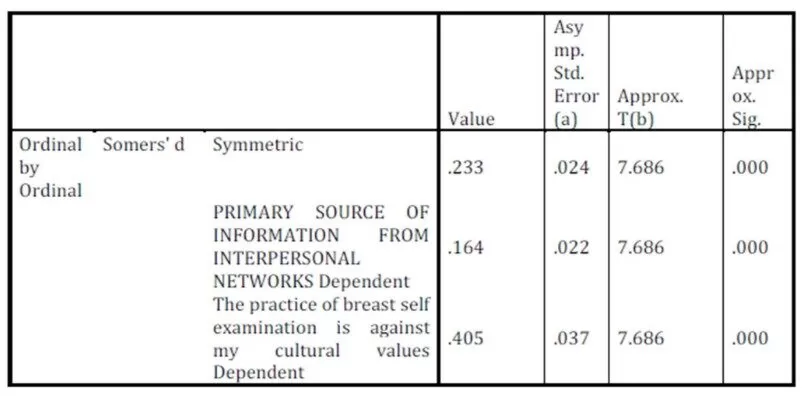

The second hypothesis which tested, there is no significant relationship between the intense use of interpersonal channels and the level of knowledge of breast cancer was rejected. From the available data on table 5 a and b, the hypothesis was rejected because the asymmetrical values in the Correlation test were less than 0.05. Table 5 b reveals that the relationship between variables is a positive and strong relationship. This study has shown that exposure to interpersonal networks of communication has an impact on the knowledge of breast cancer. The use of interpersonal networks as information sources for breast cancer has been long acknowledged by academic authorities in health communication studies and other related line of research studies.

Interpersonal channels serve as vehicles for health promotion and advocacy for breast cancer information among women in the Nigerian society. Interpersonal channels have the potential to change and form attitudes of women towards ideas or practices. Just like the mass media, interpersonal sources serve as crucial information sources for creating awareness and knowledge of breast cancer in Nigeria. Furthermore, interpersonal channels could be used in forming and changing the attitudes of women to breast cancer and the practice of breast self examination.

The third hypothesis which tested, there is no significant relationship between the sources of awareness and the practice of breast self-examination among women was rejected. This study has revealed that the sources of awareness were significant and effective on the practice of breast self-examination. Awareness is an important element of communication. It has been widely accepted that the awareness of a disease is essential before any health communication intervention could occur. Thus, awareness could also be seen as an intervention factor for health promotion and advocacy for breast cancer information. This study has shown that the sources of awareness of breast cancer actually influence the practice of breast self-examination. In essence, the use of information sources in heath promotion and interventions cannot be ignored or negotiated. The results have shown that sources of awareness have tremendous influence on the practice of breast self-examination. These results are also in consonance with Yan’s (2001) study, in which mass media, such as newspaper, television and radio were identified as the major sources of awareness of breast cancer.

Conclusion

This study has brought to the fore the inherent features of the diffusion of the innovations’ theory. If women in the Nigerian society could seek information about breast cancer from health consultants, medical experts, then the content of this theory should be taken seriously. This study has proved that mass media and interpersonal networks of communication are essential in health interventions for breast cancer and other health related issues. Thus, the core postulations of the diffusion of innovation theory have to be considered in line with health education, advocacy and intervention for breast cancer in Nigeria and the wider world.

Importantly, mass media messages should be incorporated as key machineries in media awareness campaigns for improving breast cancer care among women. This is essential because mass media messages can produce positive changes or prevent negative changes in health-related behaviours of women in South-West Nigeria.

References

1. Adaja, T. (2005). Communication and strategies for effective communication . Journal of Communication and Society, 4, 33-48.

2. Adebamowo C.A., Ogundiran, T. O., Adenipekun, A.A., Oyesegun, R.A., Campel, O.B., Akang, E.E., Rotimi, C.N., & Olopade, O.(2003). Waist-Hip ratio and breast cancer risk in urbanized Nigerian women. Breast Cancer Research, 59(18), 18-24

Publisher – Google Scholar

3. Adeji, O., Smith, O., & Robies, S. (2009). Direction in development:Public policy and the challenge of non-communicable diseases. Washington DC. World Bank

4. Anaeto, S., Onabanjo, O., & Osifeso, J. (2008). Models and theories of communication. Lagos African Renaissance Books

5. Backer, T., Rogers, E.M., & Sopory, P.(1992). Designing health communication campaigns: what works? Wenbury Parks, CA:Sage

6. Chaffee, S.H. (1986). Mass media and interpersonal channels :competitive, convergent or complementary? In Gumpert, G & Cathart, R, Inter/media, : interpersonal communication in the media world. Newyork: Oxford University Press

7. Cohen, B.C. (1963). The press and foreign policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

8. Fishbein, M., & Yzer, M.C. (2003). Using theory to design effective health behaviour interventions. Communication Theory, 13, 164-183

Publisher – Google Scholar

9. Folarin, B.(1998).Theories of mass communication.Ibadan, Nigeria.Sceptre Publishing ltd

10. Hodgetts, D. & Chamberlain, K. (2006). Developing a critical media research agenda for health psychology. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(2), 317-327.

Publisher – Google Scholar

11. Hornik, R. (1993). Public health education and communication as policy instruments for bringing about changes in behavior. Paper prepared for meeting on behavioral and social factors in disease prevention.

12. Keyton, J.(2001). Communication research: asking questions , finding answers. New York McGraw —Hill Company

13. Kreps, G. (2005). The impact of communication on cancer risk, incidence, morbidity,mortality and quality of life. Health Communication, 15, 163-171

14. Kreps, G.(2008). Health communication at the population level: principles, methods and results. In Epstein L, Culture competent care, Jerusalem, Israel: National Institute for Health Policy and Health Service Research

15. Kreps, G. & Sivaram, R. (2009). Strategic health communication across the continuum of breast cancer care in limited resource countries. Cancer Supplements, 113(8), 2331-2337

16. Kunezik, M. (1995). Concept of journalism, north and south. Bonn: Freedrick-Ebert

17. Lazarsfeld, P. F., Bernard, B., & Hazel, G. (1944). The people’s choice. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce Leask, J., Hooker, C. & King, C. (2010). Media coverage of health issues and how to work more effectively with journalists: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 10(535), 2-7

18. Lee, C. (2010). Interplay between media use and interpersonal communications in the context of healthy lifestyle behaviour: reinforcing or substituting. Mass Communication and Society, 13 (1), 48-66

19. Leslie, J. (2005). Women’s role and family health. Retrieved February 17, 2008 from htto://bixbyprogram.ph.ucla.edu/course_CHS246.pdf.

20. Mc Quail, D. (2007). McQuail’s mass communication theory . 5TH ed. London:Sage

21. McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972) The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly 34:159-170.

Google Scholar

22. Okorie ,N. (2011). Mass Media Strategies for Creating Awareness of Breast Cancer, Public Knowledge Journal, Retrievable at http://pkjournal.org/?page_id=1520. 3(1),

23. Parkin, D.M., Bray, F., Ferlay, J., & Pisani, P. (2005).Global cancer statistics CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians;55(2):74-108

Google Scholar

24. Pictrow, P., Kincaid, D., Riman, I. & Rimchart, W.(1997). Health communication: lessons from family planning. Westport, CT:Praegar

Google Scholar

.

25. Ricardo, R. (1999). Communication: a meeting ground for sustainable development. Retrieved from

26. Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: Free Press.

28. Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

28. Rogers, E. M., & Kincaid, D. L. (1981). Communication networks: Toward a new paradigm for research. New York: Free Press

Google Scholar

29. Romer, D. (1994). Using mass media to reduce adolescent involvement in drug trafficking. Pediatrics, 93, 1073-1077

30. Sandelin, K., Apffelstaedt, J, Abdullah, H., Murray, E., & Ajuluchuku, E.(2002). Breast surgery International: breast cancer in developing countries Scandinavian journal of Surgery, 91, 222-226.

Google Scholar

31. Soola, E. O. (2003). Development communication: The past, the present and the future. In Soola, E.O. (Ed), Communicating for development purposes(pp. 9-28). Ibadan: Kraft Book Limited.

32. Southwell, B. G., & Torres, A. (2006). Connecting interpersonal and mass communication: science news exposure, perceived ability to understand science , and conversation. Communication Monograph, 73 (3), 334-350

Publisher – Google Scholar

33. Story, M. T., Neumark-Stzainer, D. R., Sherwood, N. E., Holt, K., Sofka, D.,Trowbridge, F., & Barlow, S. E. (2002). Management of child and adolescent obesity: Attitudes, barriers, skills, and training needs among health care professionals. Pediatrics, 110(1), 210-214.

Google Scholar

34. WHO (2008). The global burden of disease: 2004 update.

Google Scholar

35. Wyn, R., Ojeda, V., Ranji, U., & Salganicoff, A. , (2003). Women. Work and family: a balancing

act. Retrieved September 10,2010 from www.hff.org/womenhealth

Publisher -Google Scholar

36. Yanovitzky, I., and Blitz, C.L (2000). Effect of Media Coverage and Physician Advice on Utilization of Breast Cancer Screening by Women 40 Years and Older. Journal of Health Communication: International, 5(2), 117-134

Publisher – Google Scholar