Introduction

Counterfeiting and piracy are chronic universal problems (Hamelin, Nwankwo, & El Hadouchi, 2012). Both are widespread trends that have long perplexed people and scholars all over the world. Fake and illegally produced goods are compromising public health and safety, especially in developing countries such as Nigeria. It is robbing tax revenues, incomes and legal jobs from governments, businesses and communities (Nwosu et al., 2019; Olabanjo et al., 2019). The adverse effects of counterfeiting and piracy could sap US$ 4.2 trillion from the world economy and threaten 5.4 million legal jobs shortly (Bascap, 2017). The ease of copying and sharing electronic data over the Internet has contributed to an outbreak of piracy. As a result, counterfeiting and piracy have drawn tremendous interest from academics, while causing great fear for entrepreneurs (Bush et al. 1989; Yang, Sonmez & Bosworth, 2004; Berman, 2008; Wilcock & Boys 2014; Cesareo, 2016).

Counterfeiting and piracy have long been enticing for organized criminals, with a particular focus on lucrative fields such as consumer goods, clothing, pharmaceuticals, digital media, and luxury items such as handbags and perfumes. Over the past two decades, however, the illegal practices of counterfeiting and piracy have stretched to cover nearly every public commodity. Examples are fake food and beverages, books, electrical appliances, additives, mobile phone batteries, spare parts and toys (Adelua et al., 2020a; Adelua et al., 2020b; James et al., 2020d; Nwosu et al., 2019; Adelua et al., 2020c; Adelua et al., 2020d; Aiyende et al., 2020a). The worth of this underground economy has exploded exponentially (Bascap, 2017). These illegal practices have also penetrated the beauty and cosmetics industry, causing loss of money, image and integrity; thereby endangering the industry and consumers alike. Generally, the situation is negatively impacting the profit of genuine businesses and eroding public trust. Counterfeit goods are rapidly entering the supply chain and placing producers’ uprightness at risk. The prevalence of counterfeits is a concern for almost any organization, supply chain, government and industry; and the problem is aggravating (Basu, Basu & Lee, 2015). Potential investment in research and technology is at stake because of the unfair competition arising from counterfeits (Maldonado & Hume, 2005; Olabanjo et al., 2019).

From the above premises, it is easy to understand that counterfeiting and piracy impede the growth of the beauty and cosmetics industry and the role of public relations in the matter cannot be overemphasized. Hence, public relations in this study becomes very important (Miller & Dinan, 2007; Sriramesh, & Vercic, 2003). The current research makes an industrious attempt to examine the efficacy of public relations tools in curtailing the menace of counterfeiting and piracy in the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria.

Image quality exposes many factors which influence public awareness and perception of corporate organizations. Negative image, for instance, is poor image quality (Aiyende et al., 2020b; Fayemi et al., 2020a; Fayemi et al., 2020b; Fayemi et al., 2020c; Fayemi et al., 2020d; Olabanjo et al., 2020b; Omokiti et al., 2020a). That is why proper image management through positive public relations actions is needed to control the public perception of organizations and their industries.

Statement of the Problem

The beauty and cosmetics industry has grown but is still faced with many challenges. One of the significant challenges encountered by the industry is the twin problem of counterfeiting and piracy. Undoubtedly, it has posed many threats to the continuous growth of the industry. This problem has affected both the industry and its publics such as cosmetologists, beauticians, make-up artists and women generally. Counterfeiting and piracy damage the free market economy significantly, and it also injures intellectual property rights such as trademark laws, copyrights and patents (International Chamber of Commerce, 2016).

The efforts of companies’ management and employees to build a brand is an arduous but continuous task. However, counterfeiters and pirates destroy such brand-building efforts and achievements by creating a negative image and undermining the built-up integrity of the companies and their brands. Although counterfeiting cannot be removed totally from piracy, the major problem that the research seeks to address is piracy. The importance of public relations cannot be underrated as it remains an essential tool in curtailing the impending threat of piracy in the industry. Hence, the survey will examine the effectiveness of public relations in addressing the corporate threats of piracy. It will also provide public relations solutions to the identified problems.

Study Objectives and Research Questions

This study investigates public awareness and perception of the menace of piracy in Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics industry. It examines public awareness and perception of the PR practices of selected companies in Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics industry. Also, this survey scrutinises public opinions on the effectiveness of PR activities in curtailing the menace of piracy by selected beauty and cosmetics companies in Nigeria. It unearths public recommendations on PR’s positive effect in curtailing piracy in Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics industry. Based on these objectives, the following research questions suffice:

- To what extent are members of the public aware and perceive the menace of piracy in Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics industry?

- How does the general public perceive the PR practices of selected companies in Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics industry?

- What are the public opinions on the effectiveness of PR activities in curtailing the menace of piracy by selected beauty and cosmetics companies in Nigeria?

- What are the public recommendations on PR’s positive effect in curtailing piracy in Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics industry?

Review of Related Literature

For ages, the term “cosmetics” has been known to the human race because it is human nature to desire beauty (Sartwell, 2004). Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and many other early philosophers averred that beauty is a principal thing for all human beings. They maintained that whatever is beautiful remains so, irrespective of what we feel or think. At the same time, the need to appear presentable, attractive and desirable to one another may also be regarded as a psychological cosmetising of beauty. Nevertheless, knowing the precise meaning of the term “cosmetic” from multiple sources would be important (European Economic Council, 1993).

Cosmetics are products to be rubbed, painted, powdered, sprayed, added or otherwise applied to some portion of the human body to convey attractiveness. European Regulation 93/35/EEC describes cosmetic products as any material or treatment meant to be placed in contact with the different external sections of the human body (Aziz, Taher, Muda & Aziz, 2017; Kumar, 2005). They are meant to scrub, cover, embellish, encourage, appeal or change appearance, especially facial appearance (Vance, 1999; Ali, 2018; Odiboh, Ezenagu, & Okuobeya, 2019). Cosmetics are substances used to improve or protect the human body’s appearance (Ramshida & Manikandan, 2014). Vance (1999) particularly warned against cosmetising beauty; and argued that the consequences could be grievous for the human body. These definitions are quite comparable in that they all classify cosmetics as products that enhance appearance but have no therapeutic advantages in contrast to drugs.

The fast rise in online makeup purchases can be convincing. In 2010, Internet sales were worth more than 11 billion US Dollars. As technologies grow, the cosmetics industry is also seeking to take advantage of the new developments and engage more effectively with customers. Organic beauty products are becoming ever more visible on the global market (Odiboh et al., 2020a; Odiboh et al., 2020b; Odiboh and Oladunjoye, 2019; Odiboh and Ajayi, 2019; Odiboh, Ezenagu and Okuobeya, 2019). They arose from a niche that a small number of companies had previously occupied and integrated into the mainstream market. Cosmetics have regular outlets, such as department stores and supermarkets (Vance, 1999).

As pointed out by Vance (1999), colour cosmetics (makeup) are the world’s third-largest beauty market, measured by sales. Their share remains steady at 12-13% and is aligned with the competitive growth of the market. This segment is fueled mostly by developments to which it managed to achieve market growth of 8% in 2008, even in the competitive and developed industry of Western Europe. It may also be that this traditional market is the only position where the lipstick hypothesis can be affirmed – even a 3% growth was reported in the recession year of 2009. The cosmetics industry further boosts sales by introducing items that meet the needs and preferences of diverse people with specific ethnic backgrounds, skin and hair types, and genetic features (James et al., 2020a).

Sub-Saharan Africa, dubbed the next business hotspot, is witnessing the world’s second-fastest economic growth. As a result, there are about 821 million customers in the African economy scrambling to purchase a wide variety of cosmetics and beauty products (Heyam, 2018). Due to its high birth rates and rising middle class, Africa could be the next significant growth region for cosmetics and beauty products. The market leaders – South Africa and Nigeria – will be followed by five key frontier markets: Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Ghana and Cameroon (Beauty Africa, 2016).

Counterfeiting and Piracy in the Beauty and Cosmetics Industry: The Big Issue

Growing markets tend to attract fake and adulterated products says Cesareo (2016). The beauty and cosmetics market is no exception. It cannot be overemphasised that counterfeiting and the beauty and cosmetics industry have evolved hand in hand (Bank of Industry, 2018; Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy, 2015). Counterfeiting is an act of making a product by copying or imitating an actual product’s physical appearance in an attempt to mislead consumers that it is the product of another company. Items that violate patents, violations of copyright and advertising, and naming and brand laws are accused of counterfeiting (Cesareo, 2016). Cosmetics counterfeiting represents a loss in income for the original owners of the counterfeited products and therefore decreases their share of genuine investments. This includes job losses, economic downturn and a rise in emotional stress, not to mention the serious damage to public well-being (OECD, 2016).

Counterfeit products range from twisted brand names, look-alikes and unconvincing imitations (Harvey, 1987). Thus, counterfeiting can be either deceptive or non-deceptive based on the quality of the replica (Grossman & Shapiro 1988; Nwosu et al., 2019). In the former, when the products sold are falsified, the forged ones deceive the buyer, and in the latter, the deception spreads to customers who intend to make a transaction. Consumers willingly choose the false alternative and become the counterfeiters’ accomplices (Cesareo, 2016). The issue of piracy is an intellectual property crime that is infiltrating the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria. A transitional approach is needed to address the transitional problem of intellectual property crime, locally and internationally.

While counterfeiting is about faking a product, piracy refers to the act of reproducing a product without the approval of the copyright and trademark owner according to Cesareo (2016). Counterfeiting is a simple imitation and piracy is an unauthorised production of the real product, but both are criminal acts that are punishable by law in most countries of the world. Piracy is duplicitous and intentional in denying organisations their rights to appropriate returns on investments (Harbaugh & Khemka, 2000). According to Safranski (2022), piracy is problematic for any industry that sells niche products. It comes with a negative economic impact that filters down from the management to the employees of affected organisations. It is even worse where there is no quality control. It weakens customer experience and contentment. Along with an overwhelming loss of revenue, piracy brings down individual brands in the public eye while diminishing the status of the brand owners. Whereas big organisations’ reputations are tarnished, the image of small enterprises is not spared.

Public Relations as a Tool for Limiting the Problem of Piracy

Public relations is the practice that looks after the image of an organization and seeks to gain public understanding, respect, controlled sentiment and favourable action in its favour (James et al., 2020a; Ndubueze et al., 2019; James et al., 2020b; James et al., 2020c; Ndubueze et al., 2020; Nejo et al., 2020; Olabanjo et al., 2019). Many scholars have a good understanding of public relations and are often in agreement about what it is. In all, it is a discipline that deals with an organization’s interaction with its publics. That is, what the organization is communicating to its publics and what they are reacting to (Odiboh & Ajayi, 2019). Public relations creates a better perspective and transforms negative perceptions into beneficial ones (Samson, 2018). Nwosu et al., (2020a) emphasize that, for public relations to be valued, it must be carefully applied through beneficial activities. It must deliver real value to the organization and help it to attain its corporate objectives (Nwosu et al., 2020a; Nejo et al., 2020b; Olabanjo et al., 2020a; Omokiti et al., 2020b; Salau et al., 2020a; Salau et al., 2020b; Nwosu et al., 2020b). Public relations is a veritable tool for building an organizational image. Its application in the beauty and cosmetics industry will address the issue of piracy.

Theoretical Framework

The cultivation theory forms the fundamental basis for this study. Cultivation theory was proposed by George Gerbner, who tried to determine the influence of media advocacy on viewers’ understanding of the environment they live in (Littlejohn, 2002). Gerbner realized that the dominance of television created a standard view of the world and made all cultures have conventional thinking (Ndonye, 2014). Cultivation theory contends that persuasive content over time imbues symbols, messages, images and meanings that dominate and are eventually absorbed as truth. Also, public relations practitioners must keep their message consistent until the target publics achieve behavioural change.

Research Design and Methodology

This study applied the survey method of data collection. A survey is the compilation of information from several people through responses to questions (Olabanjo et al., 2019). This type of research method allows the use of various approaches for recruiting participants, collecting data and using different information methods. Survey research may either be quantitative (using numerically graded questionnaires), qualitative (using open-ended questions) study approaches, or using both techniques. A questionnaire is the data collection instrument used in this survey method.

The questionnaire was drawn from the research questions to deduce the respondents’ awareness and perception of piracy and public relations activities in Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics industry. The survey instrument provided both open and close-ended questions about how piracy in the industry can be combated with public relations. The researcher self-administered the questionnaires to the sample size representing the population using the google form. The researcher used the google form because that is the easiest way of getting across to our study subjects. This study was conducted among 200 randomly selected people through purposive sampling. The study subjects included career women, distributors, makeup artists, and personal makeup shoppers.

Data Presentation and Discussion

Data obtained from the fieldwork are analysed and presented in tables of frequencies and percentages. The tables show how exposed the publics are to the public relations activities of the beauty and cosmetics industry, their level of awareness of these public relations activities, and opinions about piracy in the beauty and cosmetics industry. Also, what do they suggest to curtail the threats piracy has on the industry?

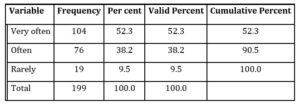

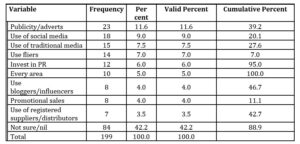

Table 1: How often the respondents shop for cosmetics

Table 1 shows that out of 199 respondents, 104, (52.3%) said they shop for beauty and cosmetics very often; and 76, which represents 38.2% of the respondents affirmed that they often shop. In contrast, 19, which represents 9.5%, affirmed that they rarely shop for beauty and cosmetics products. The data above shows that the respondents shop for beauty and cosmetics at one point or the other, hence, only a few of the respondents affirm shopping rarely, while none affirmed never shopping.

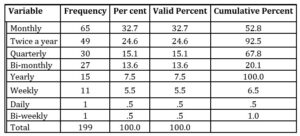

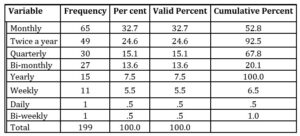

Table 2: Periods of respondents’ shopping for cosmetics

Table 2 shows that the majority (32.7%) of the respondents stated that they shop monthly for beauty and cosmetics products. On the other hand, 24.6% of the respondents said they shop for beauty and cosmetics products twice a year. However, 15.1% of the respondents stated that they shop quarterly. In comparison, 13.6% affirm that they shop bi-monthly.

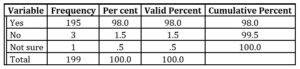

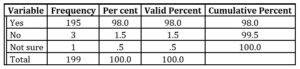

Table 3: Awareness of the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria

As noted in Table 3, 195 which represents 98.0% of the respondents are aware of Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics sector, and three which represents 1.5% of the respondents are not aware of Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics sector. This result shows that almost all respondents are aware of Nigeria’s beauty and cosmetics sector.

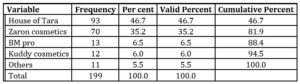

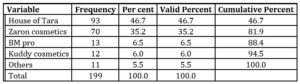

Table 4: The beauty and cosmetics industry respondents are familiar with

Table 4 reveals that 46.7% of the respondents agree that they are familiar with the House of Tara as a beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria. On the other hand, 35.2% of the respondents are aware of Zaron cosmetics as a beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria. In comparison, 6.5% are aware of BM Pro as a beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria. From this outcome, it is obvious that the respondents are more aware of House of Tara and Zaron cosmetics as beauty and cosmetics brands in Nigeria.

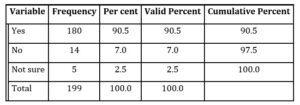

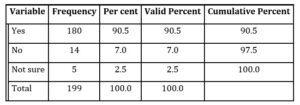

Table 5: Awareness of public relations activities

Table 5 shows that 90.5% of the respondents agree that they are aware of the beauty and cosmetics industry’s public relations activities in Nigeria; 7.0 % responded negatively. By contrast, 2.5% said they were not certain. Based on this finding, it is clear that the respondents are aware of the beauty and cosmetics industry’s public relations activities.

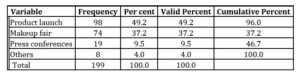

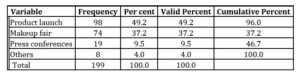

Table 6: Respondents’ familiarity with public relations activities

According to Table 6, 49.2% of the respondents agreed that they are aware of a product launch as a public relations activity in the beauty and cosmetics industry. Meanwhile, 37.2% of the respondents mentioned that they are aware of the makeup fair as a public relations activity they carry out. Only 9.5% of the respondents mentioned press conferences. In comparison, 4.0% of the respondents mentioned others which means makeup fairs and product launches as the significant public relations activities they know.

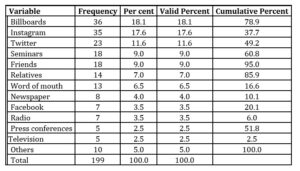

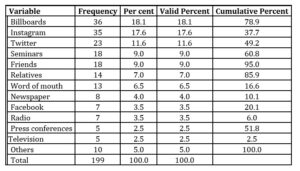

Table 7: How respondents became aware of public relations activities of beauty and cosmetics companies

According to Table 7, 18.1% of the respondents listed billboards as a means by which they became aware of the beauty and cosmetics industry’s PR practices. On the other hand, 17.6% mentioned Instagram, 112% said through Twitter, 9.0% said they became aware through friends, 9.0% also mentioned seminars, 7.0% through relatives, and 6.5% mentioned word of mouth. This means the primary tools through which people become aware are billboards and Instagram predominantly.

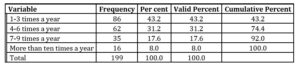

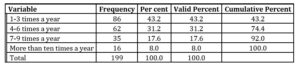

Table 8: Exposure to public relations actions of beauty and cosmetics companies

From Table 8, 43.2% of the respondents mentioned that they are only exposed to these actions 1-3 times a year. Meanwhile, 31.2% mentioned 4 – 6 times a year; 17.6% mentioned 7 – 9 times a year, while only 8.0% only mentioned that they are exposed to these actions more than ten times a year.

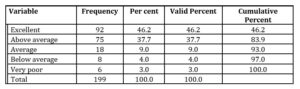

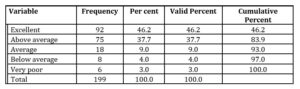

Table 9: How respondents rate the success of public relations activities in fighting piracy in the industry

Table 9 shows how the respondents rate the success of public relations in fighting piracy. A simple majority (46.2%) stated that the activities are excellent, 37.7 % stated that it is above average, and 9.0% stated that it is average. In comparison, 4.0% and 3.0%, respectively, stated that it is inadequate.

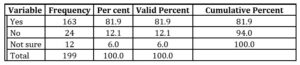

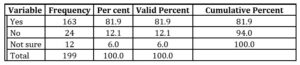

Table 10: To know if quality public relations activations changed respondents‘ perception of the beauty and cosmetics industry

Table 10 indicates that 81.9 % of the respondents believe that high-quality public relations efforts have improved their view of the beauty and cosmetics industries; 12.1 % responded negatively. By comparison, 6.0 % said they were not certain. From this result, it is clear that the beauty and cosmetics industry’s public relations efforts go a long way toward improving consumer image.

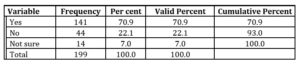

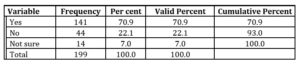

Table 11: Respondents’ satisfaction with the PR activities carried out in the beauty and cosmetics industry

As shown in Table 11, 70.9% answered in the affirmative that they were satisfied with the beauty and cosmetics industry’s public relations activities, and 22.1% answered in the negative. In comparison, 7.0% stated that they are not sure if they are satisfied or not.

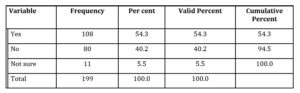

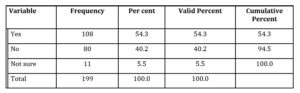

Table 12: Whether the respondents want improvement in the delivery of public relations activities

According to Table 12, 54.3% agreed that they would want beauty and cosmetics to improve in the deliveries of their activities, and 40.2% said no. In comparison, 5.5% of the respondents said they are not sure.

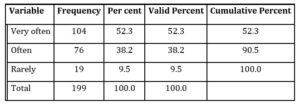

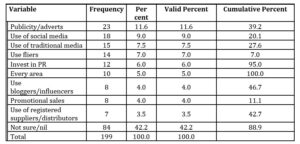

Table 13: Respondents’ area of improvement in the delivery of the public relations actions

The respondents listed some of the areas they would want the beauty and cosmetics industry to improve in the delivery of their public relations activities. In Table 13, 42.2% mentioned that they are not sure. However, 11.6% mentioned publicity/adverts, 9.0% mentioned social media, 7.5% traditional media, 7.0% mentioned the use of fliers, and 6.0 mentioned that they should invest in more public relations.

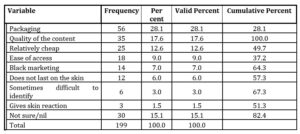

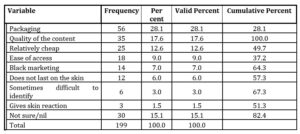

Table 14: How respondents identify fake beauty and cosmetics products

Table 14 shows how the respondents can identify fake beauty and cosmetics companies. A majority, 28.1%, said through the packaging. However, 17.6% said through the quality of the content, 15.1% are not sure, 12.6% mentioned price, 9.0% ease of access, 7.0% mentioned black marketeering, 6.0% indicated that it doesn’t last on screen, 3.0% said sometimes it is difficult to identify while only 1.5 said it gives skin reaction. This table shows that the principal way through which the respondents identify counterfeit products is through the packaging.

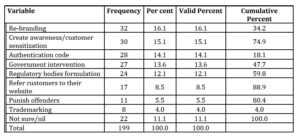

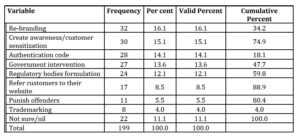

Table 15: Measures respondents think can be taken to curtail Piracy threats

Table 15 shows the measures that the respondents suggested in curtailing the threats of piracy in the beauty and cosmetics industry. A majority (16.1%) of the respondents suggested re-branding; 15.1% mentioned that companies should create awareness and sensitize consumers, and 14.1% suggested the use of an authentication code. Meanwhile, 13.6% suggested government intervention. Furthermore, 12.1% suggested regulatory bodies; 11.1% said they are not sure, or they do not know; 8.5% said to refer customers to their official website. Lastly, 5.5% said to punish offenders, while 4.0% suggested trademarking. The use of the authentication code remains the leading measure suggested by the respondents in curtailing the menace.

Discussion of Findings

Data obtained from the study serve as the basis for interrogating the questions guiding this research. The analysis would generally cover the respondent’s awareness of the public relations tools used to reduce the rate of piracy in the beauty and cosmetics industry.

Public Awareness of selected beauty and cosmetics companies’ PR activities

This research investigated respondents’ awareness of the beauty and cosmetics industry’s public Relations’ practices in Nigeria. Based on the survey results, the analysis showed that the respondents are well aware of the beauty and cosmetics industry’s public relations practices. The public relations activities that the respondents are cognizant of include product launches and makeup fairs, which were identified by the majority. Deduced from this is that the respondents are aware of cosmetics and beauty public relations activities, and they can specifically identify these events.

Public relations tools used by selected beauty and cosmetics companies

This study brought to the fore the public relations tools through which the respondents became aware of the public relations activities of the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria. From the data generated from Table 7, essential tools through which the respondents became primarily aware of the PR activities are billboards, followed by Instagram and Twitter. Two of these tools are social media which means social media and one is Out of Home. The three are vital tools for creating awareness for PR activations in the industry under focus.

Public awareness and perception of PR practices in the beauty and cosmetics companies in Nigeria

Tables 10 and 11 show how the respondents perceive the PR practices of the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria. The beauty and cosmetics industry’s public relations efforts are well-known to the respondents. Also, the industry’s target groups have a positive opinion about the companies under focus. They were satisfied with the beauty and cosmetics industry’s public relations activities. This result denotes that the PR activities of the beauty and cosmetics industry are effective in influencing the thoughts of the public. If PR does not warn and affect public actions and decisions, then the primary goal of establishing a mutual relationship would not be achieved.

Effectiveness of PR activities in curtailing piracy in the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria

Based on the data generated from the survey, the respondents’ rating of the success of public relations in fighting piracy is fairly high if 46.2% “excellent” is added to the 37.7% “above average”. This is an approval of the public relations fight against piracy. The importance of public relations in fighting piracy is further emphasized by this result. Therefore, public relations tools are necessary for the war against piracy in the beauty and cosmetics industry, with the belief that positive results will help to fine-tune the industry’s image.

Maintaining and enhancing PR and its positive effect on the industry

Based on the data from the survey, the respondents gave insights into the areas of improvement in the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria. That is the area of improving the delivery of their activities. Findings show the suggested areas of improvement. They are the use of publicity, advertising and social media. Also, the use of authentication codes and government intervention are significant measures for winning the battle against piracy. Also, customer sensitization advocacies about how to tackle piracy in the industry are suggested. All these suggestions are significant outcomes that would be useful for the anti-piracy endeavours of the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study affirms that PR is necessary for creating awareness for the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria and is also a veritable tool in fighting piracy in the industry. In building a strong relationship between an industry and target groups of people, public relations remains useful as proven by this study. Therefore, the importance of public relations in the beauty and cosmetics industry can never be overemphasized. Thus, to curtail piracy in the beauty and cosmetics industry, the use of public relations tools must be used continuously until piracy is curtailed to the barest minimum.

Based on the aims, findings and conclusion of this study, the following recommendations should be considered by all stakeholders in the beauty and cosmetics industry in Nigeria and other countries with similar experiences:

- The beauty and cosmetics industry needs to avail itself the social media for public engagement and interaction. It will bring them closer to their consumer-publics. That way, they can continuously sensitize users about the side effects of patronizing fake products on their skin as well as the danger to their health in general.

- Governments at all levels need to create regulatory bodies that will watch the activities of the beauty and cosmetics industry and enforce laws that can decimate piracy. Through these bodies, the government can always execute market raids and destroy any shop that sells pirated cosmetics and beauty products.

- Companies need to rethink their product packaging and ensure constant rebranding to outsmart pirates. They also need to trademark their brand and create Units in the PR department which would use the trademark benchmark to identify pirated versions of their products and bring the perpetrators before the law.

References

- Adelua, M., Odiboh, O., Aiyende, O. and Omokiti, O. (2020a), ‘Community Relations Activities of Tourism, Arts and Culture in Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Adelua, M., Odiboh, O., Nejo, O. and Fayemi, O. (2020b), ‘Public Relations Professionals’ Works at a State Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture: A Layout of Viewpoints’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Adelua, M., Odiboh, O., Olabanjo, J. and Ndubueze, N. (2020c), ‘Banking Public Relations and Customers’ Consciousness in Nigeria’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Adelua, M., Odiboh, O., Oyedepo, T., Olabanjo, J. and James, D. (2020d), ‘Professional Public Relations in Nigeria’s Banking Industry’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Aiyende, O., Odiboh, O., Adelua, M. and Omokiti, O. (2020b), ‘Practitioners’ Usage of Electronic Public Relations at A-State Transport Ministry in Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Aiyende, O., Odiboh, O., James, D., and Salau, J. (2020a), ‘Public Awareness and Perception of Electronic Public Relations at The Lagos State Traffic Management Authority, Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Aleksandra, Ł. and Miroslav, Ł. (2013), Global Beauty Industry Trends in The 21st Century. Knowledge, Management and Innovation International Conference, June 2013 19-21.

- Aziz, AA., Taher, ZM., Muda, R. and Aziz, R. (2017), Cosmeceuticals and Natural Cosmetics. In R. Hasham, Recent Trends in Malaysia Medicinal Plants Research (Chapter 6, pp.126-175). Penerbit, UTM Press.

- Bank of Industry (2018), Cosmetics and Beauty Care Products. [online] Retrieved June 6, 2019. Available at: https://www.boi.ng/cosmetics-and-beauty-care-products/

- Bascap (2017), Confiscation of Crime Proceeds. [online] Retrieved June 6, 2019. Available at: https://cdn.iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2017/01/ICC-BASCAP-Confiscation-of-the-Proceeds-of-IP-Crime-2013.pdf.

- Basu, MM., Basu, S. and Lee, JK. (2015), Factors Influencing Consumer’s Intention to Buy Counterfeit Products. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 15(6) 123-140.

- Beauty Africa (2016), African Cosmetics and Beauty Industry. [online] Retrieved July 23, 2022. Available at: http://beautyafrica.com/whyafricacosmeticsbeautyindustry/

- Berman, B. (2008), Strategies to detect and reduce counterfeiting activity. Bus Horiz 51(3):191–199. DOI: 10.1016/j.bushor.2008.01.002.

- Bush, RF., Bloch, PH. and Dawson, S. (1989), Remedies for product counterfeiting. Bus Horiz 32(1): 59–65.

- Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy (2015, September 28), Promoting and Protecting Intellectual Property in Nigeria Advocacy. [online] Retrieved June 23, 2022. Available at: International Chamber of Commerce website: http://www.iccwbo.org/

- Cesareo, L. (2016), Counterfeiting and Piracy. Springer Briefs in Business, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-25357-2_1

- European Economic Council (1993), Directive 93/35/EEC of 14 June 1993 amended for the sixth time Directive 76/768/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to cosmetic products. Official Journal L 151, 23/06/1993 P. 0032 – 0037.

- Fayemi, O., Odiboh, O., James, D. and Olabanjo, J. (2020a), ‘Public Relations in Secondary Schools: A Case Study of Private and Public Secondary Schools Ota, Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Fayemi, O., Odiboh, O., James, D. and Aiyende, O. (2020b), Professional Public Relations Activations and Tools Used by A-State Development and Property Corporation in Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Fayemi, O., Odiboh, O., Nejo, O. and Salau, J. (2020c), ‘Community Observations of the Public Relations Activations of a State Ministry for Housing in Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Fayemi, O., Odiboh, O., Oyesomi, K., Nwosu, E. and Olabanjo, J. (2020d), ‘Professional Public Relations Practices in High Schools in Nigeria’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Grossman, GM. and Shapiro, C. (1988), Foreign counterfeiting of status goods: national bureau of economic research, Cambridge, Mass, USA.

- Harbaugh, R. and Khemka, R. (2000), Does Copyright Enforcement Encourage Piracy? Claremont Colleges Working Papers in Economics, No. 2000-14, Claremont McKenna College, Department of Economics, Claremont, CA.

- Hamelin, N., Nwankwo, S. and El Hadouchi, R. (2012), “Faking brands”: Consumer responses to counterfeiting. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 12(3), 159–170. DOI:10.1002/cb.1406.

- Harvey, MG. (1987), Industrial product counterfeiting: problems and proposed solutions. J Bus Ind. Mark 2(4), 5–13.

- Heyam, SA. (2018), Cosmetics and Beauty Products Review Comprehensive Review Article. Acta Scientific Pharmaceutical Sciences 12 (2018), 74-80.

- International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). (2016, September, 28), Promoting and Protecting Intellectual Property. [online] Retrieved June 5, 2019. Available at: https://cdn.iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2017/01/Promoting-and-Protecting-Intelle actual-Property-in-Nigeria.pdf.

- James, D., Odiboh, O., Adelua, M. and Fayemi, O. (2020a), ‘Public Awareness and Perception of Public Relations Activations at a Universal Education Board in Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- James, D., Odiboh, O., Aiyende, O. and Salau, J. (2020b), ‘Public relations activations in a State Ministry of education, Lagos, Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- James, D., Odiboh, O., Nwosu, E. and Fayemi, O. (2020c), ‘Public Relations Practices and Bootlegging in Nigeria’s Publishing Industry: A Focus on STIRLING-HORDEN, HEBN and SAFARI’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- James, D., Odiboh, O., Olabanjo, J. and Adelua, M. (2020d), ‘Publishing, Public Relations and the Public in Ibadan, Nigeria’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Kumar, S. (2005), Exploratory analysis of the global cosmetic industry: major players, technology and market trends. Technovation, 25(11), 1263–1272. DOI: 10.1016/j.technovation.2004.07.003.

- Littlejohn, S. (2002), Theories of Human Communication (7th ed.), Wadsworth, Albuquerque, NM.

- Maldonado, C. and Hume, E. (2005), Attitudes toward counterfeit products: an ethical perspective. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 8(2), 105-117.

- Miller, D. and Dinan, W. (2007), A century of spin: How public relations became the cutting edge of corporate power. Pluto Press, London.

- Ndonye, M. M. (2014), “Theoretical Foundation of Advocacy in Communication: Kenyan Perspective.” Egerton University, Njoro Kenya: Academia.Edu. pp. 40 ─ 53.

- Ndubueze, N., Odiboh, O., Adelua, M and Fayemi, O. (2020), ‘Image Management Through Public Relations in Nigeria’s Food and Beverages Industry’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Ndubueze, N., Odiboh, O., Nwosu, E., and Olabanjo, J. (2019), Awareness and perception of public relations practices in Public tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, 10-11 April 2019, Granada, Spain.

- Nejo, O., Odiboh, O., James, D. and Fayemi, O. (2020a), ‘Public Relations Activities of a State Parks and Gardens Agency in Promoting Environmental Sustainability in Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Nejo, O., Odiboh, O., Omokiti, O., and Adelua, M. (2020b), ‘Awareness and Impact of the Public Relations Activities on a State Ministry of the Environment in Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Nwosu, E. Odiboh, O., Olabanjo, O. and Fayemi, O. (2020a), ‘Made-In-Nigeria Automobile Industry and Public Relations Actions: An Examination of Public Awareness and Perception’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Nwosu, E., Odiboh, O, Ndubueze, N. and Olabanjo, J. (2019), ‘Public awareness and perception of public relations activities in government agencies in Nigeria’ Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, 10-11 April 2019, Granada, Spain.

- Nwosu, E., Odiboh, O., Oyedepo, T., James, D. and Adelua, M. (2020b), ‘Made-In-Nigeria Automobiles and Public Relations: Three Professionals’ Perspectives’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Odiboh, O. and Oladunjoye, A. (2019), ‘Application of integrated marketing communication tools for promoting computers in Nigeria’ Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, 10-11 April 2019, Granada, Spain.

- Odiboh, O., Amodu, L. and Ekanem, T. (2020a), ’Marketing and Communication of Herbal Products as Male Reproductive Solutions in Lagos, Nigeria’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Odiboh, O. and Ajayi, F. (2019), ‘Integrated Marketing communication and carbonated drinks consumers in Nigeria: A consumerist analysis’ Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, 10-11 April 2019, Granada, Spain.

- Odiboh, O., Ezenagu, A. and Okuobeya, V. (2019), ‘Integrated marketing communication tools and facials consumers in Nigeria: Applications and connexions’ Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, 10-11 April 2019, Granada, Spain.

- Odiboh, O., Fasanya, O., Adegoke, K., Afolabi, O. and Ofor, A. (2020b), ‘Social Media in Online Learning among Accounting Business Students in Nigeria: Africa in View’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- OECD. (2016), Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, European Union Intellectual Property Office.

- Olabanjo, J., Odiboh, O., Adelua, M. and Fayemi, O. (2020), ‘Activation of public relations by professionals in Nigeria: A case study of Zaron cosmetics and House of Tara’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Olabanjo, O., Odiboh, O., Nwosu, E. and Ndubueze, N. (2019), ‘Public relations practices in local government and traditional institutions in Nigeria’ Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, 10-11 April 2019, Granada, Spain.

- Omokiti, O., Odiboh, O., Aiyende, O. and James, D. (2020b), ‘Awareness and Usage of Social Media as e-Public Relations Tool in a Health Ministry and Agency in Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Omokiti, O., Odiboh, O., Salau, J. and Nejo, O. (2020a), ‘Health Information and Social Media: Patients’ Perception of Selected Primary Health Care Centres, Yaba, Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Ramshida, AP. and Manikandan, K. (2014), Cosmetics Usage and Its Relation to Sex, Age and Marital Status. International Journal of Social Science and Interdisciplinary Research ISSN 2277-3630 IJSSIR, 3(3), 23-39.

- Safranski, J. (2022), What is the impact of piracy on businesses? [online]Accessed September 14, 2022. Available on https://www.redpoints.com/blog/impact-of-piracy/

- Salau, J., Odiboh, O., Adelua M. and Fayemi, O. (2020a), ‘Farmers On Digital Media Usage and Agricultural Information in Lagos, Nigeria’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Salau, J., Odiboh, O., Omokiti, O. and Nejo, O. (2020b), ‘Public Relations Practitioners, Poverty Alleviation Programmes for Farmers and State Agricultural Development Authority: A Qualitative Study,’ Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-4-0, 1-2 April 2020, Seville, Spain.

- Samson, MH. (2018), Public relations in corporate reputation management: A case of Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation. Journal of Media and Communication Studies, 10(9), 113–117. DOI:10.5897/jmcs2016.0502.

- Sartwell, C. (2004), Six Names of Beauty. New York, Routledge.

- Sriramesh, K. and Vercic, D. (2003), The global public relations handbook: Theory, research, and practice. New York, Routledge.

- Vance, J. (1999), Beauty to Die for: The Cosmetic Consequence. San Jose, toExcel.

- Wilcock, AE. and Boys, KA. (2014), Reduce product counterfeiting: An integrated approach. Business Horizon 57(2), 279–288.

- Yang, D. Sonmez, M. and Bosworth, D. (2004), Intellectual property abuses: how should multinationals respond? Long-Range Plan 37(5), 459–475. DOI: 10.1016/j.lrp.2004.07.009.