Introduction

The fiscal role of a tax instrument means that taxes affect the amount and the structure of state budget revenues and expenditures. Taxes are incorporated in the prices of products and services. As a result, the volume of consumption of goods and services is also influenced, so is the production volume. Investment into production of goods or services requires capital; the domestic one or from abroad e.g. in the form of foreign direct investments. Investors made a decision, which may also be influenced by the state aid, in the form of “tax holidays”; which is a useful instrument to attract foreign direct investors.

The social role of taxes is also significant. It is reflected in the appropriate tax burden of individual population groups. Taxpayers sensitively perceive tax scandals which should be solved by the state. States should work on the improvement of legislation to prevent their occurrence. The intervention of the state is necessary to create a tax system that motivates people to work and do business honestly. If the state does not act adequately when the scandals about tax havens have come to the light, by doing nothing of inference, it supports tax evasions which has negative consequences for the entire national economy. Tax havens have allured investors and entrepreneurs by low tax liability for many years. The functioning of tax havens and offshore centers causes tax evasion and thereby it leads to reducing governments´ tax income in the countries that have higher tax rates. It influences their budget significantly. International organizations are trying to map individual countries with zero or low tax rates and businesses established in tax havens owing to growing numbers of tax evasion or tax fraud. The OECD, encouraged by the G20 group of finance ministers has a long history of developing initiatives to reduce the illegal tax evasion through hiding assets and income, profits and gains in tax havens, e.g. one of the main initiatives – the OECD Model Tax Treaty (Exchange of Information).

The following three priority areas of the tax policy are highlighted in the resolution of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament: (Saxunová, 2016)

- To strengthen the internal market´s benefits through the tax policy.

- To fight against tax fraud, tax evasion, aggressive tax planning and tax havens.

- To enforce effective tax coordination to secure a long-term growth-oriented economic policy.

If the states of the European Union succeed in meeting the objectives of priority areas, it should contribute to the growth of the economy and the social and economic status of the member states´ population.

Objectives and Methodology

The objective of this scientific paper is to examine the phenomenon of a tax haven and to analyze existing criteria which can assist in determining countries considered as tax havens; and to study the most important characteristics and features of tax havens. The aim of this paper is to point out which countries are tax havens from the European Union´s point of view. Comparison, analysis and synthesis, deduction as scientific methods are applied. The first part of the article focuses on compiling theoretical thresholds associated to tax havens, their classifications, what are the possibilities to limit their activities, and focuses on determining tax havens´ most important features. Additionally, the anti-tax haven policy is also considered. In the second part of the paper, we focus on tax havens and their impact on the biggest multinational companies in the USA, their profits and subsidiaries in tax havens, the GDP and the Slovak and Czech entrepreneurs´ enterprising activity. Secondary data provided by Bisnode and the Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy have been analyzed in the period from 2008 to 2017.

Theoretical Framework in the Literature Review

The start of using tax-advantaged entities in the modern sense is dated to the period between the two world wars. In the 1920s, US and Scandinavian companies registered their vessels under the flags of Liberia and Panama. Wealthy people used offshore trusts and holdings recorded in the Bahamas and the Normandy Islands to protect their assets. Large corporations established captive insurance companies in Bermuda and the Cayman Islands, which has become the largest offshore banking center. (Miller, Oats, 2016). The real boom of the offshore centers occurred in the second half of the 20th century. The introduction of a new legal form of IBC (International Business Company) was a significant breakthrough. The British Virgin Islands had an important role in expanding IBC. In 1984, the possibility of establishing the simplified form of companies (IBC) was enabled by the British Virgin Islands´ legislation. The British Virgin Islands´ success helped the dictator Noriega to come to power in Panama which was the most important offshore center at the time. Panamanian lawyers moved their clients´ companies to the British Virgin Islands because they did not want to lose profit from establishing tax-advantaged entities. In coming years, IBC companies gained huge popularity. The success of the British Virgin Islands was an inspiration to the countries that have introduced similar legislation. (Epi.sk, 2007)

A country or an independent region, a principality or other type of legal jurisdiction where taxes are levied at a low rate is the image that conjures up when debated about tax havens. “An Offshore Financial Center (OFC) have become a jurisdiction (often a country) that provides corporate and financial services to non-resident companies on a scale that is incommensurate with the size of its economy. Traditionally, OFCs are assumed to be small, low-tax jurisdictions in remote location. In practice, determining which countries are in fact OFCs is nontrivial and as such a highly debated topic.” (Garcia-Bernardo, Fichtner, Takes and Heemskerk, 2017). Significant factors for choosing a jurisdiction which attracts the investors to incorporate the company in this country due to low taxes and other favorable conditions are, as follows:

- reliable means of communication;

- political and economic stability;

- good reputation;

- sophisticated corporate laws;

- rapid incorporation process,

- user friendly process of opening a bank account, zero fees or keeping the fees to the minimum

- no accounting requirement

The growth of tax haven usage is the subject of a considerable interest of the governments worldwide. Entrepreneurs are trying to hide their profit in tax jurisdictions, and thereby avoiding tax obligation in the original country. A tax haven is “a place where people pay less tax than they would pay if they lived in their own country” (Sofield, 2018). Gleeson (2018) says that there is no generally accepted definition of tax havens. Saxunová, Nováčková and Kajanová (2018) state, that “countries of the tax paradise are characterized by strong reduction or non-existence of corporate or personal income taxes and at the same time by the possibility of their repatriation abroad, by foreign exchange deregulation, by the existence of relatively liberal license policy, by the lack of compulsory minimal reserve, by absenting rules for liquidity bank management or capital adequacy, by the limited regulation of collective investment, by the existence of very strict banking confidentiality, by political stability, by excellent information, telecommunication infrastructure or other advantages”.

The notion of a tax haven is also characterized by Palan et al. (2010, p. 8) as a phenomenon that is hardly identifiable. Tax havens are countries or places that provide adequate autonomy to accept own tax regulations and finance laws. “They all take advantage of this autonomy to create legislation designed to assist non-resident persons or corporations to avoid the regulatory obligations imposed on them in places where those nonresident people undertake the substance of their economic transactions”. Another characteristic offered by most tax havens is some degree of secrecy; the above-mentioned advantage allows individuals and corporations subjected to national law to do everything anonymously. Access and establishment simplicity of business entities in a tax haven is another attractive tax-haven feature. Tax havens can be characterized as jurisdictions that provide certain benefits to entities in the form of a reduced tax burden. It is implemented on the grounds of favorable tax legislation having been enacted in these jurisdictions, which represents a) their quasi “competitive advantage” for attracting capital which even may come from illegal activities or b) their instruments to optimize tax obligation. Gupta (2017) adds self-promotion as another feature of tax havens. Tax havens usually promote themselves as the best destination for offshore financial centers.

Kudrle (2003) states that tax haven performs three types of functions that are frequently combined: a) produce goods and services; b) shift tax claims among jurisdictions; and c) hide tax claims. These functions are reflected in 4 types of tax havens occurring most frequently, therefore, Miller and Oats (2016) distinguish four types of tax havens:

- Production havens – real activity is transferred to the tax haven, there is tangible value added – Ireland (12,5% tax rate), this tax policy attracts FDIs.

- Base havens – no/very low taxes on all business income – colonies or formal colonies of onshore jurisdictions

- Treaty havens – low withholding taxes on money flowing into or out of haven, often no tax while it remains there and no withholding tax when it flows back out – suitable for intermediate holding companies, – the Netherlands with very favorable networks of DTT’s.

- Concession havens – countries offering particular tax incentives or benefits, (e.g. Swiss branch of a Dutch company the Netherlands offers more concessions than others, Belgian coordination centers -headquarter haven.

Miller and Oats (2016, p. 544) highlight rationale for tax havens usage highlighting the goal of a multinational enterprise to minimize the global tax liability of the group by:

- a) searching for the way of “minimizing taxable income arising in high-tax jurisdictions;

- b) preventing or delaying earnings and/or investment income from entering high-tax jurisdictions by parking them in a very low-tax country until needed elsewhere within the group; and

- c) sitting operation (especially financial operations) in low-tax countries wherever possible to cut the MNE’s average tax rate on its global profits.”

Other attractions are favorable tax regime, favorable legal environment (allowing MNEs to adopt innovative financial products fast and flexibly) and a preferential regulatory system.

The Gordon Report, prepared for the US Treasury, constituted basic characteristics of a tax haven:

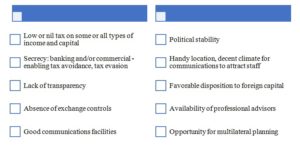

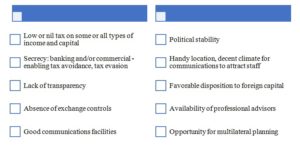

Table 1: Gordon’s Basic Characteristics of a Tax Haven benefocial to company

Source: Own elaboration based on (Gordon, 1981)

OECD (2009) defines tax havens as territories that must have the following characteristics:

- Zero or nominal tax rate on the relevant income – tax havens usually offer zero or almost zero tax rates on the income reported by corporations registered in the concrete tax haven jurisdiction. That is the reason why these countries seem to be a safe place for foreign companies to reduce tax burden. This is one of the most important criteria for characterizing tax havens. On the other hand, there are many countries providing similar allowances with well-regulated legislation and cannot be classified as tax haven.

- Lack of effective exchange of information – this is a critical aspect of secrecy. Tax havens try to protect personal financial information of companies working in the area. For example, the secrecy of information in Swiss banks is legendary; they do not cooperate with authorities. On the other hand, they help fraudsters to hide income and commit tax fraud.

- Lack of transparency – the next important feature of tax havens is disarranged legislative, legal and administrative tools. It is based on secret tax deals and comfort letters to the companies. They offer clandestine negotiations taking place behind-closed-doors for interested parties.

- No significant activities – there is no need for establishing significant local presence – tax havens try to make establishing and managing companies by low tax rates and secrecy easier for investors. It positively influences the creation of “letter-box” companies. Letter-box companies are just represented by an address belonging to a law company or an accounting firm in the other part of the world.

Tax havens may be used as a base for manufacturing operations but selecting them as a location seat for bank deposits and intellectual property, insurance business or other business involving mobile capital is a prevailing option. The attractiveness of many tax havens is their specialization. For example, Bermuda, Guernsey and the Isle of Man offer advantages to insurance companies and organizations providing investment in certain funds. Most of transactions in these jurisdictions consist of passive income transfers (interest and royalties) and fictitious payments. (Tax Justice Network, 2017).

Anonymity provided by tax havens is beneficial for companies because of their being interested in not revealing secret information about businesses registered in this area which tax havens’ jurisdiction allows. Some countries do not require bookkeeping, reporting accounting information on companies established in that territory. Other favorable characteristics include the absence of inheritance and gifts taxes and minimizing interference in business offices.

Garcia-Bernardo, Fichtner, Takes and Heemskerk (2017) investigated offshore financial centers, which were studied and their “data covered over 77 million ownership relations, which together form a large network in which value flows from subsidiaries to shareholders. From it millions of global corporate ownership chains were extracted. The resulting fine-grained insight enabled them not only to see where value originates and ends up, but also exactly where it originated. Based on their research they identify “two types of OFCs:

- Sink-OFC: a jurisdiction in which a disproportional amount of value disappears from the economic system.

- Conduit-OFC: a jurisdiction through which a disproportional amount of value moves toward sink-OFCs.”

The sink-OFC number of a selected country, which fulfills definition of a sink-OFC center, indicates roughly how much more value sinks in a given country as compared to what should sink in it based on the size of its economy. For example, in the British Virgin Islands, approximately 5235 times too much value ends. Other known sink-OFC centers are, for instance: Taiwan, Jersey, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Samoa, Liechtenstein, Curacao, Marshall Islands, Malta, Mauritius, Luxembourg, Nauru, Cyprus, Seychelles, Bahamas, Belize, Gibraltar, Anquilla, Liberia, St. Vincent & Grenadines, Guyana, Hong Kong, Monaco. The conduit-OFC number of a selected country, which fulfills definition of a conduit-OFC center, indicates roughly how much more value is channeled in and out of this country towards a sink, as compared to what should be based on its economy’s size. For example, roughly 20 times too much value is routed through the Netherlands (Garcia-Bernardo et al., 2017). Other conduit centers are, for example: United Kingdom, Switzerland, Singapore, Ireland. For examples the results for the Netherlands measured by OFC meter are as follows: NL: value in: $740 billion, value out: $380 billion, factor out 18.6, factor in 22.5. (Garcia-Bernardo et al., 2017).

Anti-Tax Haven Policy in the World of Digitalized Technology

Tax havens are used legitimately and illegitimately. Corporations use them legitimately if they invest capital and perform operational or financial activities in the tax haven and respect full reporting obligation by disclosing income, profits and gains due to the tax authority in which the taxpayer is resident. It may lead to tax savings if a system of double tax relief by exception may be applied in the country of residence (it is usually applied to active income, a credit relief is applied only to passive income). The exemption method is usually restricted for the use of corporate taxpayers, individuals and trusts must use the credit method. To discourage illegitimate use of tax havens is almost impossible. A harmful combination of a dishonest taxpayer and a tax haven operating a policy of secrecy results in hiding the income arisen in tax haven before taxation in the country of taxpayer’s residence for which it will be impossible to find out about it. Nowadays, anti-haven legislation may be applied to corporate taxpayers and individuals if interested, hardly can they be stopped from illegitimate use of tax havens.

Measures introduced by the OECD, such as OECD Model Tax Treaty, the establishment of the Global Forum (its goals are to reduce the availability of secrecy for would-be tax evaders and possible improvement of small tax havens being able to act in accordance with information exchange procedures), the Mutual Convention on Administrative Assistance in Taxation (multilateral treaty for the exchange of information and with the option of assistance in tax collection), and in 2014 Common Reporting Standard (for the exchange information for tax purposes, accompanied by a multilateral treaty allowing mutual tax authorities’ communication) are voluntary, countries show their attitude for abandoning banking secrecy and willingness of exchanging information that will complicate hiding offshore income for the citizens of non-tax haven countries.

Possible measures against tax havens:

- Legitimate:

i) on the national level: a) Anti-haven legislation;

b) Information exchange and better cooperation between tax authorities

c) Economic and political sanctions

d) Legal action against intermediaries facilitating investment into tax havens

ii) on the supranational

level: a) Taxpayer’s amnesties

- Illegitimate:

i) on the national level a) Taxpayer’s amnesties

ii) on the supranational

level: a) Economic and political sanctions

b) Information exchange and better cooperation between tax authorities

To eliminate harmful tax competition, there is a need for an important step towards the tax haven countries that still are or were considered as tax havens. Modern technology is also an obstacle for tax havens such as, electronically realized payments via electronic cash registers; that many countries have been introducing, radical reduction of cash payments, limited to small-volume transactions of a minimalized principal make it harder to transfer capital abroad illegally. In addition, new trends of sharing economy namely; the development of cryptocurrency market, is a growing competitor for tax havens. Online platforms enable the recording of P2P traceable transactions with the big difficulties of tracing them, if not being traceable at all. This information if reported or made available to tax authorities, can contribute to perform data matching analysis resulting in enhancing tax compliance.

Technology can be used as a tool of expanding the capabilities of tax administrations, of enhancing the effectiveness of compliance activities, improving taxpayer services, and lowering compliance burdens. On the other hand, also, those who plan to avoid tax payments, will use the technology, as well, for their purposes and some of the latest developments are the potential risks arising from digitalization. Certainly, the governments must act and prepare the legislation and policy needed to reflect the technology development, or to establish the principles governing the needed forms of analysis.

International Taxation Rules Challenges

Digitalization is spreading in a rapid pace and changes the way businesses operate. These changes have placed pressure on the basic concepts underlying the existing international tax rules which were created almost a century ago. For instance, the “origin of wealth” principle is questionable for the case of a modern globalized world, because when this concept was possible to be applied, factors contributing to the value created by MNEs were relatively immobile and required intensive use of labor and tangible assets.

Today, the non-resident enterprise taxation is dependent on the constituted rules requiring physical presence to determine nexus and allocate profits. The fundamental concentration of the existing tax framework has been to align the allocation of taxing rights with the location of the economic activities undertaken by the enterprise, including the people and property that it employs in that activity. (OECD, 2018). The 2015 Base Erosion Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project renovated the international tax rules substantially, supported by the principle that the location of taxable profits should be aligned with the location where economic activities and value creation take place. “However, the effectiveness of these rules may be challenged by the ongoing digitalization of the economy to the extent that value creation is becoming less dependent on the physical presence of people or property” (OECD, 2018, 169.).These challenges were classified into three broad categories, which substantially overlap:

Nexus: The continual increase in the potential of digital technologies and the reduced need in many cases for extensive physical presence in order to carry on business, combined with the increasing role of network effects generated by customer interactions, can raise questions as to whether the current rules to determine nexus with a jurisdiction for tax purposes are appropriate.

Data: The growth and sophistication of information technologies that have accompanied the digitalization of the economy has permitted an increasing number of companies to gather and use information across borders to an unprecedented degree. This raises the issues of how to attribute value created from the generation of data through digital products and services, and of how to characterize a person or entity’s supply of data in a transaction for tax purposes (e.g., as a free supply of a good, as a barter transaction, or in some other way). Further, the fact that users of a participative networked platform contribute to the user generated content, with the result that the value of the platform to existing users is enhanced as new users join and contribute, may raise other challenges.

Characterizations: The development of new digital products or means of delivering services creates uncertainties in relation to the proper characterization of payments made in the context of new business models, particularly in relation to cloud computing. (OECD, 2018)

States and Jurisdictions Considered as Tax Havens

According to Gleeson (2018), Switzerland became the first real tax haven after World War I. This state tried to be neutral during the war. Switzerland´s aim was to preserve low tax rates, because high infrastructure costs were not incurred as in other countries. After World War I., many European states significantly increased their tax rates to support reconstruction after the devastation. This step led to the increase of capital inflows into Switzerland because of the more favorable taxation rules. Currently, there is no consensus on the number of tax havens around the world. Taking the latest estimation into account, approximately 150 countries offer favorable conditions to investors. Some tax havens are entire countries like Bermuda or just states or territories like Nevada. The list of countries considered as tax havens is constantly changing.

The European Union distinguishes tax havens as EU black-listed and EU gray-listed countries. The black list countries have not adopted necessary tax evasion measures, also called EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes. The gray list, or the EU list of the state of play of the cooperation with respect to commitments taken to implement tax good governance principles, was created for the more obedient countries. The European Union has identified three main criteria when it comes to assessing whether a state should be on the black list:

- Transparency of tax system – Does the country or jurisdiction follow the instructions on the information exchange? The country is focused on the involvement of an international cooperation and participation in combatting tax fraud making use of the latest technology.

- Fair taxation – Fair Tax Competition – Does the country or jurisdiction have a harmful tax system? Does the country or jurisdiction use anti-BEPS measures?

- Real Economic Activity – Does the jurisdiction´s tax rates or tax system stimulate fake tax structures? (European Council, 2018e), can the country trace cash transfer over the borders?

Referring to these criteria, the European Union assessed 92 tax jurisdictions. The EU has opened a debate with these countries whose tax system creates conditions for tax evasion or tax fraud. It included requests and suggestions for remedial actions in the mentioned area. The black list contained states that have not taken any steps in this direction. (European Council, 2017a). In January 2018, the EU ministers agreed on a list of non-cooperating countries to suppress the presence of tax havens. According to actual information from the European Council (2017a; 2017b; 2018a; 2018b), on 23rd January 2018, the black list included the following countries:

The change occurred on March 13, 2018 when the Council removed Bahrain, the Marshall Islands and Saint Lucia from the black list and added the Bahamas, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and the US Virgin Islands. According to the European Council (2018c), “since the list was first published, Bahrain, the Marshall Islands and Saint Lucia have made commitments at a high political level to remedy EU concerns. In the light of an expert assessment of those commitments, the Council decided to move three jurisdictions from annex I to annex II“; which means from the black list to the gray one.

The European Council says that the implementation of the removed countries´ commitments will be carefully monitored. When the list was published in January, the Council agreed to postpone the Caribbean countries screening those impacted by hurricanes in September 2017. The process of screening was reopened in January 2018. The Bahamas, Saint Kitts and Nevis and the US Virgin Islands were added to the black list since these jurisdictions have failed to make commitments at a high political level:

- a) The Bahamas ease offshore structures to attract profits without real economic substance.

- b) Saint Kitts and Nevis have a harmful preferential tax system.

- c) “US Virgin Islands do not apply any automatic exchange of financial information, have not signed and ratified, including the jurisdiction they are dependent on, the OECD Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance as amended, have a harmful preferential tax regime and did not clearly commit to amending or abolishing it, and do not apply the BEPS minimum standards”. (European Council, 2018d).

The actual black list includes the following countries:

The European Council´s decision (2018c) also has an impact on the gray list consisting of 59 countries. The European Council agreed to add Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, the British Virgin Islands and Dominica to the gray list of the EU. The mentioned addition was confirmed by obligations made to address failures identified by the EU.

At this moment, we have no information about the concrete criteria that should be implemented in Bahrain, the Marshall Islands and Saint Lucia. The gray list includes countries and jurisdictions in which the legislation should be improved in the criteria of transparency, taxation and Anti-BEPS Measures.

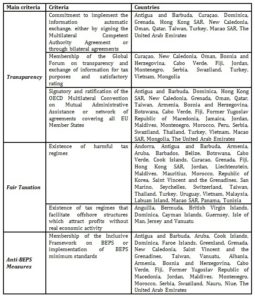

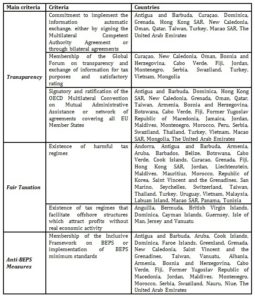

Table 3 presents three main criteria and significant issues that should be solved in the countries on the gray list; they should be implemented in the mentioned jurisdictions; moreover, there is a list of the countries committed to participate, particularly, in criteria implementation together with the EU respecting commitments taken to implement tax good governance principles.

Table 3: Countries’ Cooperation State of Play with the EU Implementing Tax Good Governance Principles

Own elaboration based on European Council (2017b; 2018b; 2018c; 2018d)

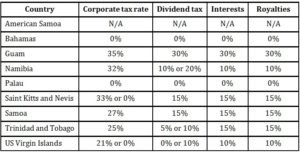

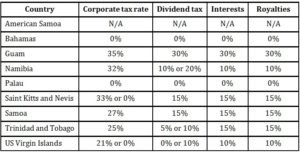

As it has already been mentioned, these countries are interesting for entrepreneurs due to low tax rates. The following table shows corporate tax rates, dividend taxes, interest and royalties for 2017 on the basis of available data for each EU blacklisted country. There are cases where the income of the legal entities, sole proprietors, partners or individuals is exempted entirely from taxation, or corporations are exempted from double taxation. It is obvious that; there is no information available on tax rate and taxation in American Samoa from reliable sources, Bahamas are tax free haven, no taxes on income, no withholding taxes on the payment of dividends, interest or royalties. (PWC, 2017b) In Palau, no corporate tax is levied, but indirect tax – turnover tax; a gross revenue tax of 4% exists. In Trinidad and Tobago, a 25% corporate tax rate applies to profits up to 1 million Trinidad dollars. Minimum tax is determined at the rate of 0.6% of revenue. In the US Virgin Islands, the corporate tax rate has been reduced to 21% from 35% “and alternative minimum tax repealed as from 1 January 2018. Gross receipts tax of 5% is also imposed. Surtax of 10% applies on total income tax liability.” (DELOITTE, 2018a)

Table 4: Corporate Tax Rate and Withholding Tax Rates in the „the Black List“Countries

Own elaboration based on (DELOITTE, 2018a,b), (EY, 2017), (DELOITTE, 2017), (PWC, 2017a,b), (BDO, 2017).

Tax authorities on the multinational level are forced to act due to corporations’ effort to avoid taxation, to create legislation that is at least limiting the activity of tax havens. Advanced technology may assist to both counterpart parties. Technological progress and digitalization of society is spreading rapidly in each sphere of everyday life and it alters the way how business operate. The basic concepts underlying the existing international tax rules, which were created almost a century ago, are shaking at the roots, because of these changes. For instance, the “origin of wealth” principle – is questionable in some cases of a modern globalized world, because in the past economic factors contributing to the value created by multinational enterprises were relatively immobile and required intensive use of labor and tangible assets. The ongoing growth in the potential of digital technologies and the declined need for operational leverage (extensive physical presence) in order to continue doing business, combined with the strengthening role of network effects generated by customer interactions, can raise questions e.g. whether the current rules to determine nexus with a jurisdiction for tax purposes are appropriate Today, the non-resident enterprise taxation is dependent on the constituted rules requiring physical presence to determine nexus and allocate profits. The fundamental concentration of the existing tax framework has been to align the allocation of taxing rights with the location of the economic activities undertaken by the enterprise, including the people and property that it employs in that activity. (OECD, 2018).

The 2015 Base Erosion Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project renovated the international tax rules substantially, supported by the principle that” the location of taxable profits should be aligned with the location where economic activities and value creation take place. However, the effectiveness of these rules may be challenged by the ongoing digitalization of the economy to the extent that value creation is becoming less dependent on the physical presence of people or property” (OECD, 2018, p.169).

Results and Discussion

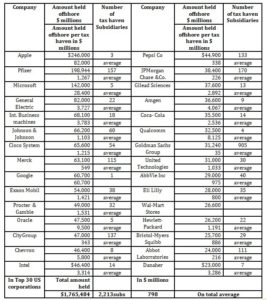

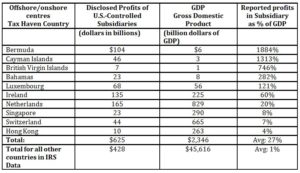

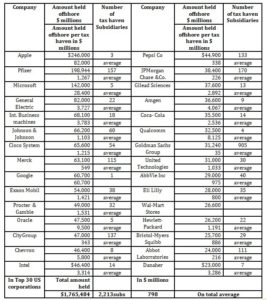

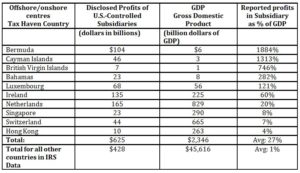

Tax Havens Development in Selected Countries. Top 30 largest American (USA) corporations represent an illustration (see Table 5) that informs on the capital held offshore and on the number of their tax haven subsidiaries, and the average amount per tax haven. Tax Justice Network estimates the capital in amount of $21 – 32 trillion (USD) in tax havens. This amount represents from 24 to 32 percent of total global investments. Over one million organizations are registered in the British Virgin Islands. Cayman Islands are also famous; thanks to 40 of the world´s biggest banks that possess a license in this country and they hold more than one trillion of American dollars as deposits. Goldman Sachs holds $31.24 billion offshore, but “reports of having 905 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens, 537 of which are in the Cayman Islands despite of not operating a single legitimate office in that country, according to its own website.” (Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2017).

Table 5: Corporations’ Capital Held in Tax Havens & their Tax Haven Subsidiaries’ Number

Source: Elaborated based on Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy (2017)

In 2014, the US Public Interest Research Group found out that tax losses in the United States amounted to $184 billion per year due to large corporations such as Apple, Microsoft, Facebook or Pfizer, which benefit from tax-planning opportunities offered by tax havens that enable to reduce their tax burden through lower or zero tax rates. Between 2010 and 2012, Pfizer reported earnings – $43 billion (American dollars) and paid zero taxes. In 2013, Microsoft had $76.4 billion abroad, which helped the company to save taxes of $24.4 billion. (Gleeson, 2018).

Table 6 presents the most notorious tax havens located in the Caribbean countries, in Europe and Asia highlighting the profits of the U.S.; the controlled subsidiaries that proved operating in the tax havens, expressed as the percentage of tax haven’s country GDP. Overall, if all the Fortune 500 companies paid taxes on their profits in the United States of America, the country would get an additional $752 billion. In 2016, the US budget deficit amounted to $585 billion.

Table 6: American Multinational Corporations in 2012 and Reported Profits of their Subsidiaries Located in Tax Haven Country

Source: Own elaboration on the source of: Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy (2017)

Tax Havens and Slovakia and Czech Republic’s Involvement

Tax havens have attracted foreign companies for many years. The capital, not collected as tax revenues, could improve governments’ budgets and the governments could use this capital for many public projects. Slovakia is divided into regions, there are big differences in the economic development. There are regions which are legging, and their GDP is below 75% of GDP of the EU’s GDP average values. The objective of the EU’s regional policy is strengthening convergence of economic and social development, and regional politics should be a driver of employment and competitiveness. The discrepancy in the growth of well-off being is an evidence that European policy in this area is not sufficiently efficient. (Delaneuville, 2017a, p.1863). The lack of capital for the development of regions not only in Slovakia is visible worldwide. The tax havens motivate companies to behave unethically and egoistically by attracting them with unusually preferential treatment. No doubt higher tax revenues have a positive impact on public finances volume offering even an opportunity of public debt reduction (Wefersova, 2017); but it would affect also regional development supported by strengthening their investment potential from domestic or attracted foreign investors’ capital resources. (Delaneville, 2017b).

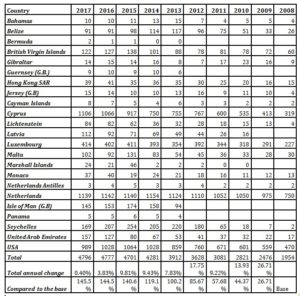

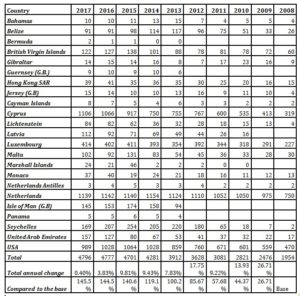

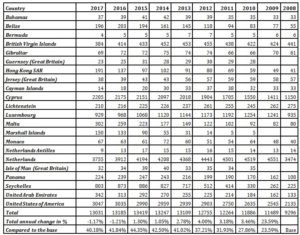

Table 7 shows the interest of Slovak and Czech corporations in tax havens from 2008 to 2017, the number of companies registered in the mentioned countries and the changes of their interests (expressed as year-to-year percentage changes). The number of Slovak companies in tax havens, at the end of the year 2017, reached 4,796. It represents an increase of about 0.5% (19 companies). This number is the highest in the history of the Slovak Republic, despite the regulations to fight against tax evasion. The Slovak entrepreneurs´ interest in tax havens is continually rising, with a growth pace slowing down in 2017, though. The pace of growth achieved the lowest level; 0.4%, in the last decade. The number of Slovak companies increased. Last year, the biggest decline of the Slovak companies was in the USA (-39%) and the Seychelles (-38%). Last year winners; the top three increases in new tax havens for Slovaks in 2017, was Cyprus (an increase – new 40 companies) followed by the United Arab Emirates and Latvia. This island is the home for 1,106 parent companies of Slovak subsidiaries. in 2017. Nowadays, Slovak companies are managing more than 10.5 billion euros in tax havens. (www.bisnode.sk).

As visible from the available data in Table 7, Slovak companies do not have owners in the countries from the EU´s black list, except the Bahamas, which are long term connections between the Bahamas and Slovak companies. The number of Slovak corporations in this country reached its maximum in 2013 (15 companies). Currently, it is only 10. Slovak enterprises in the countries that are the EU’s gray-listed tax havens were also monitored. The following section contains information about Slovak and Czech companies in relation to tax havens.

Table 7: The Number of Slovak Companies in Tax Havens

Own elaboration based on www.bisnode.sk

In 2017, 748 companies deferred their profits offshore in the above-mentioned countries. Referring to the analyzed data and countries, only 15.8% of the analyzed companies are present in tax havens that are registered by the EU.

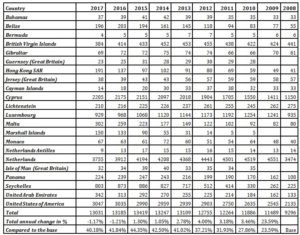

Table 8: The Number of Czech Companies in Tax Havens in the decade of 2008-2017

Own elaboration based on www.bisnode.cz

The number of Czech companies that book their profits in tax havens, at the end of the year 2017, reached 13,031. It represents a decrease of 1.2% (154 companies). The owners from tax havens control 2.7% of Czech entities and their investment represent more than 409 billion Czech korunas. The Czech entrepreneurs´ interest in tax havens reached its peak in 2015 and since 2015, it has decreased which is a proof that 2015 BEPS has driven certain success in Czech Republic unlike in Slovakia, where the growth continues but not in such a rapid pace as before 2015. Currently, the number of Czech subsidiaries with parent companies in tax havens is the lowest in the last five years. A decrease has been observed in more than 60% of the analyzed companies. Traditional destinations such as the Netherlands and the Republic of Seychelles lost the most. On the other hand, countries like Hong Kong and the United Arab Emirates were successful in attracting investors, (www.bisnode.cz). As evident from table 9, Czech companies are not EU´s black listed enterprises, but the Bahamas is. Czech entities in this country reached its maximum in 2014 (42 companies). The linkage of Czech enterprises to the countries that are on the EU´s tax havens gray was also monitored with 2 227 companies recorded in 2017 in these countries. Referring to analyzed data and countries, only 17.37% of the analyzed enterprises are present in tax havens that are registered by the EU.

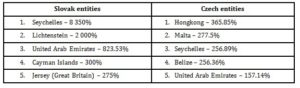

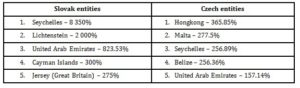

The period of analyzed sample covers 10 years (2008-2017). Since 2008, the interest of Slovak companies in the analyzed countries has grown by 145.45%, while in the Czech Republic only by 40.18%. On the other hand, the number of Czech companies in tax havens is 2.72 times higher compared to Slovak enterprises. Table 9 presents the top 5 tax havens where the most remarkable growth in percentage was observed, related to the examined period of 2008-2017. Table 9 highlights the largest increase of Slovak companies in the Republic of Seychelles over the past 10 years, by 8 350% compared to the interest of our neighbors in Hongkong SAR that has increased by only 365.85%. The shortcomings of Slovak and Czech Republic is a disclosure of limited information related to the capital invested into individual representatives of tax havens, nor the entities which shifted the capital offshore. In the USA, 58 countries of 500 Fortuna list discloses the information online, how much profit was shifted and how much of taxes could have been obtained otherwise. The companies that collect and record this information in Slovakia provide this information for a fee.

Table 9: Slovak and Czech Enterprises in the Tax Havens – Top 5 percentual growth

(2008 – 2017)

Source: Own elaboration based on (www.bisnode.sk, www.bisnode.cz)

Conclusion

International organizations pay attention to countries that provide zero tax rates and other benefits to foreign investors. The European Union has created the EU lists of tax havens; black list and gray list. The black list includes countries that have not undergone the necessary tax evasion measures. It is also called EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes. The gray list, or the EU list of the state of play of the cooperation with respect to commitments taken to implement tax good governance principles, was created for the more obedient countries. When assessing whether the state is on the black list, the European Union uses three main criteria: transparency of the tax system, fair taxation and the involvement of the country in international cooperation in the fight against tax fraud.

The research interest highlights the gap where is room for research to be conducted, focusing on goods or property that the tax havens capital is used for, if for example, tax evasion capital is not invested into weapons instead of medicine research (to support vaccination in Africa). Capital hidden before taxation is higher than official development aid to developing countries to support sustainable development goals. Wu’s research results (2017, p.349) show that globalisation influenced military expenditures in Japan, Korea, and Thailand. Moreover, military expenditure caused globalisation only in Singapore. Some of this countries are becoming conduit OFCs.

Individual countries invest a big effort into capturing tax evasion and tax fraud. Nevertheless, it is almost impossible to determine their extent. There are various estimates of losses caused by fraudsters to countries every year, but exact numbers are not available. The only information disclosed in connection with tax evasion is the number of companies in tax havens. As the research shows, the interest of Slovak and Czech companies in these countries recently has a declining tendency unlike US companies. The number of Czech businesses in these countries is almost three times higher than the number of Slovak companies. On the other hand, the growth of Slovak entities in tax havens has taken off by 145.45%, compared to 40.18% rise of Czech entities.

Tax reporting laws enable corporations to dictate how, when, and where they disclose foreign subsidiaries and abuse tax havens’ lenient tax rules for their own goals and allow them to take advantage of tax loopholes without attracting governmental or public scrutiny. Congress, EU Parliament or other national parliaments can and should act to prevent corporations from abusing offshore tax havens, which in turn would restore basic fairness to the tax system, bring finances for valuable public programs related to the security, health and education, possibly lower state deficits, and ultimately improve the market functioning. Researcher teams of Novackova (2017) and Peracek (2017, 2018) emphasize that the fundamental prerequisite of managing tax compliance process is the high-quality tax legislation and Palan (2010), Beno (2016), Kajanova (2015) and Olvecka (2016) highlight also that fair business environment and legislation that are to be ruling new technology progress within industry 4.0 will play a role in the coming future as well.

Incentives for companies shifting profits offshore should be ceased, the most egregious offshore loopholes in the tax code should be definitely closed and transparency should become priority. Lawmakers should reject proposals enabling companies to shift profits offshore to avoid taxes. Technology used in the business assists to trace the cash movement and this makes the attempts of tax evasions harder. The practice of shifting corporate income to tax haven subsidiaries reduces government revenue at the stake of higher taxes paid by citizens, lowers financing available for government programs, or increases state deficit.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Reference

Beňo, M. (2016). The role of world trade organization in the globalization process. – In: Globalization and its Socio-Economic Consequences, Proceedings Part 1 . – Žilina : Univerzita Žilina, 2016 ; S. 166 ; CPCI-SSH

Daverio & Vaughan (2016), in OECD (2018), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293083-en

Delaneuville, F. (2017a), ‘Influence of New Public Management on the development of regional government in Europe: Critical analysis of the process of regionalization in Slovakia’ Proceedings of the 29th International Business Information Management Association Conference: Education excellence and innovation management through Vision 2020: From regional development sustainability and competitive economic growth (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9860419-7-6, 3-4 May 2017, Vienna, Austria, 1863-1875.

Delaneuville, F. (2017b), ‘Bratislava et le desert slovaque’, Proceedings of the 30th International Business Information Management Association Conference: Vision 2020: Sustainable Economic development, Innovation Management, and Global Growth (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9860419-9-0, 8-9 November 2017, Madrid, Spain, 3208-3217.

Garcia-Bernardo, J. Fichtner, J. Takes, F.W. & Heemskerk, E.M. (2017), ´Uncovering Offshore Financial Centers: Conduits and Sinks in the Global Corporate Ownership Network´, Scientific Reports 7, article 6246, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06322-9

Gleeson, D. (2018), 103 Tax Haven Escapes, Vivid Publishing, Australia.

Gordon, R.A. (1981), ‘Tax Havens and their Use by US Taxpayers – An Overview’. [Online], IRS Publication1150 (4-18) [Retrieved February 20, 2018], http://www.archive.org/details/taxhavenstheirus01gord

Goudin (2016) in OECD (2018), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293083-en

Gupta, R. (2017), Recent Trends In Transfer Pricing – Intangibles, GAAR and BEPS, Bloomsbury, India.

Kajanová, J. (2015), ‘Vývoj priamych daní na Slovensku’, Maneko, 2015,VII (1), 17-26.

Kurdle, R.T., (2003), The Campaign Against Tax Havens: Will it Last? Will it Work? Standard Journal of Law, Business and Finance 9, Stan JL Bus&Fin (2003-2004)

Miller A., Oats, L. (2016), Principles of International Taxation. 5th , Bloomsburry publishing, West Sussex, UK, pp. 543-590.

Milosovicova P., Novackova D., and Wefersova. J. (2017) Medzinarodne ekonomicke pravo. 1. vyd. – (International Economic Law). Praha : Wolters Kluwer, Czech Republic, p.282

Milošovičová, P., Mittelaman, A., Mucha, B., Peráček, T. (2018). The particularities of entrepreneurship according to the trade licensing act in the conditions of the Slovak Republic. – In: Innovation management and education excellence vision 2020 . – Norristown : International business information management association (IBIMA), 2018 ; pp.. 2736-2745

Ölvecká, V. (2016). The analysis of tax licence consequences on global business environment. Glo-balization and Its Socio-Economic Consequences: International Scientific Conference: University of Žilina, 2016 (vol 4), pp. 1604-1612, [Online], [Retrieved March 1, 2017] http://ke.uniza.sk/sites/default/files/content_files/proceedings_part_iv.pdf

Palan, R., et al. (2010), Tax havens: How Globalization Really Works, Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London.

Peráček, T., Nosková, M. and Mucha, B. (2017) Selected issues of Slovak business environment, Economic and social development-“Managerial issues in modern business” (Book of Proceedings) Varazdin : Varazdin development and entrepreneurship agency, 254-259.

Saxunová, D. (2016), ‘Daňová politika na Slovensku a v Európskej únii’ Európska ekonomická integrácia v kontexte aktuálneho vývoja a výziev pre členské štáty Európskej únie, ISBN 978-80-7552-497-3 Wolters Kluwer, Praha.

Saxunova, D., Novackova, D. and Kajanova, J. (2018), ‘International Tax Competition Complying with Laws: Who are its Beneficiaries? ’, Journal of Eastern Europe Research in Business and Economics, Vol. 2018 (2018), Article ID 145385, DOI: 10.5171/2018.145385

Sofield, C. (2018), ‘Meaning of „tax haven“ in the English Dictionary’. Cambridge Dictionary. [Online], [Retrieved February 20, 2018], https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/tax-haven

Stokes et al. (2014) in OECD (2018), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293083-en

Vaughan and Hawksworth (2014) in OECD (2018), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293083-en

Wu, T. P. (2017). The relationship between globalisation and military expenditures: Evidence from Eastern Asia. International Journal of Economic Policy in Emerging Economies, 10(4), 349. doi:10.1504/ijepee.2017.10010139

European Council. (2017b), ‘Outcome of proceedings: The EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes’. [Online], [Retrieved February 21, 2018], http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-15429-2017-INIT/en/pdf

European Council. (2018b), ‘´I/A´ Item note: The EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes: Report by the Code of Conduct Group (Business taxation) suggesting the de-listing of certain jurisdictions’. [Online], [Retrieved February 21, 2018], http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5086-2018-INIT/en/pdf

European Council. (2018d), ‘The EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes: – Changes due to commitments received from jurisdictions affected by hurricanes = Adoption’. [Online], [Retrieved March 14, 2018], http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6945-2018-INIT/en/pdf

(2018), ‘Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS’, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris.

www.bisnode.cz,

www.bisnode.sk

Note

Nexus : The nexus rule to determine jurisdiction to tax a non-resident enterprise. Under most tax treaties, business profits derived by an enterprise are taxable exclusively by the state of residence unless the enterprise carries on business in the other state (i.e., the source state) through a permanent establishment (PE) situated therein. This is sometimes called the “nexus” rule (e.g., Articles 7 of the OECD and United Nations (UN) Model Tax Conventions), as it identifies the profits that are taxable by a country by reference to their relationship to a PE. This threshold generally requires a certain level of physical presence of the foreign enterprise in the taxing jurisdiction, either through a “fixed place of business” or through the actions of a “dependent agent” (Articles 5 of the OECD and UN Model Tax Conventions).

Allocate Profits: The ALP is broadly applied in a similar manner in two cases: when a country has taxing rights over the business profits of a resident taxpayer (e.g., Article 9 of the OECD and UN Model Tax Conventions) or when these business profits are attributable to the PE of a nonresident taxpayer (e.g., Articles 7 of the OECD and UN Model Tax Conventions).