Introduction

The globalized world is becoming faster and unpredictable. Yet, what is almost unvaried is the basis of our society – family and its values, Masulis et al. (2011). According to Goehler (1993), “family influence constitutes the family business”. In view of this reason, family businesses are the foundation of every economy. They dominate world trade and generate 70-90% of GDP, De Massis et al. (2017). According to the latest statistical data, they create 50-80% of the jobs worldwide (Family Firm Institute, 2017). In Europe, family businesses are even more important as Botero et al. (2015) and Pindado, et al. (2012) claimed. In Spain, small and medium – sized entreprises are regarded as non-exporting businesses (Fernández and Nieto, 2005). They represented 70% of the gross domestic product (Maloni et al. 2017). Moreover, they also contribute to the economic growth in South and East Asia, Latin America and Africa (González and García-Meca, 2014).

The above are not just phrases, but a provable fact by many studies in recent years. Compared to big and non-family businesses, family businesses are more resilient in crisis and thus respond faster to market opportunities, which extend their life cycle (Carr and Bateman, 2009), (Kontinen and Ojala, 2011). Moreover, they act as different roles in society, such as the basis for serving regions, the bearers of traditional products and the natural supporters of their surroundings (Gomez-Mejia, Makri and Larraza-Kintana, 2010), (Graves and Thomas, 2006).

Specific attributes within a family business is a double-edged sword. These attributes— family, managers and owners are systematically arranged in the Three Circle Model, according to Tagiuri and Davis (1996) and Moore (2009). The Family Business Triangle model (Rivers, 2015) shows the complexity of reconciling economic and family goals. On the other hand, Nacht (2018) highlighted the difficulty to determine the extent to which family goals are pursued, as the commitment level of the family management, the influence of the family on the enterprise, or the intention of future generation to inherit the business are unquantified.

The differences between family and non-family businesses are mainly in the area of personnel and economics (Aronoff and Ward, 2016). Family businesses aim at both financial and non-financial objectives. Their managers aim for sustainable growth and maximizing the long-term value of the business (McCormick, 2016). The same authors pointed out that family businesses are more conservative and risk-averse, and their successors tend to abide by tradition. The same study also identified the unique resources in family businesses, such as human capital, financial capital and lower control costs. Contrarily, the goal of non-family businesses is primarily the return on investment of the owners (Nacht, 2018).

The aim of this study is to evaluate the influence of family representation on the enterprise using a statistical method of correlation analysis. The structure of the study is as follows – Section 1 introduces the objectives of the research and the basic aspects of the family business. Section 2 presents findings from the related literature. Section 3 discusses the methodology of this research. Section 4 presents the outcomes and evaluation of the influence of family representation on the company. Section 5 concludes the main results and recommendations for companies and future studies.

Literature Review

The definition of “family business” differs among studies (Chittoor and Das, 2007; Sharma, 2004; Anderson and Reeb, 2003; Habbershon and Williams, 2003 and Sharma et al. 1999). Habbershon and Williams (2003) defined family business as “the unique bundle of resources a particular firm has because of the systems interaction between the family, its individual members and the business”. Chua, Chrisman and Sharma (1999) defined it as “a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families.” Sharma (2004) classifies family firms as famiy businesses “only if the family retains voting control of the business and multiple generations of family members are involved in the day-to-day operations of the firm”.

However, most of the definitions always take the following factors into account: the number of family members participating in the share capital; the amount of share capital owned by family members; the representation of the family in top management; and the intention to hand over the business to the successor generation. The most important prerequisite for success in future generations of a company is based on the personality of the founder, and the intensity and quality of family involvement in the company (Aronoff and Ward, 2016).

Family businesses are considered the largest job source in the private sector, and their multi-generation nature strengthens the stability of the economy as they are more capable of survivingthrough the economic recession (Machek and Hnilica, 2015). Due to the high level of trust among family members, family businesses are very flexible and able to quickly adapt to changes in the socio-economic environment (Doney, 1998). Family businesses are able to respond more flexibly in frequently- changed policies, such as VAT rates (Randová, Krajňák and Friedrich, 2013). Besides, family businesses have a significantly higher equity ratio than other businesses, which supports both the stability of the enterprise and the overall economy fundamentally (Bloom, 2007).

The definition of “family business” gives great importance to the business environment in the Czech Republic. It helps family businesses to identify laws that are related to them, so they can respond quickly and flexibly without unnecessary bureaucracy. In May 2019, a definition of “family business” has finally been introduced to the Czech Republic (European Parliamnet, 2015). It is possible to statistically and realistically evaluate the impact of family businesses on the economy (Kalls and Probst, 2013). It can also launch structural changes, or possibilities of tax relief as well as other aspects of the income tax (Krajňák, 2018). In Spain, for example, it has been concluded that if an entrepreneur invests his capital in a company and it is a family business, there is a tax reduction in those companies (Déniz and Suárez, 2005).

The disagreement between family members is a constant problem. The existing research focused on assessing the impact of that on the performance of family businesses (Astrachan et al. 2002; Ruherford et al. 2008 and Holt et al. 2010) and their financial performances (Ruiz Jiménez et al. 2015). Klein et al. (2005) identified three dimensions of the family’s influence, based on their F-PEC method, portraying the influence of the family on the enterprise through three pillars: Power, Experience and Culture. Studies of Merino et al. (2014) on more than 500 small and medium sized entreprises and the results have shown that differentiating family dimensions with F-PEC has new impacts on the business. Frank et al. (2017) created a multidimensional indicator (FIFS – Family Influence Familiness Scale) comprising six dimensions: (1) ownership, management and control; (2) the knowledge level of active family members in their family business; (3) sharing information among active family business members; (4) transgenerational orientation; (5) the link between family and employees; and (6) the identity of the family business.

Since there is limited literature in the Czech Republic, the influence of family business on the development of the business environment and GDP creation is mainly based on foreign studies. Worldwide family business is conducted by the study programs in these universities: Cambridge Institute for Family Enterprise, Center for Family Enterprise and Ownership at Jönköping International Business School in Sweden and Jyväskylä University in Finland. For Czech universities, only subjects related to the problems are offered, for instance VŠFS Prague and VŠB-TU Ostrava. Centers for Family Business exist at several American universities. A similar center was established at the University of Economics in Prague in 2016.

The Family Firm Institute (located in Boston, USA) is known as the most prestigious family business association in the world, founded in 1986, together with the publication of the first issue of the Family Business Review in 1988, can be considered as the origin of the scientific research of “family business” (Sharma et al. 2012). In the European Union, the European Family Businesses Federation has been operating in Brussels since 1997. It brings national associations together and represents family businesses with a long history. In the Czech Republic, the Association of Family Companies and the Club of Family Companies within the Association of Small and Medium Enterprises aim to enforce the notion of “family business” in Czech legislation. An accurate definition should be the main requirement to support the family businesses (Machek and Hnilica, 2015).

The method of correlation analysis in family businesses has been discussed by Sonfield and Lussier (2004), Sonfield and Lussier (2005), Sonfield and Lussier (2009) and Sonfield et al. (2005). In their 2009 study, the authors examined, in a transnational context, the integration of family members and non-family leaders into family businesses. The sample (N = 593) of family businesses was made from six countries with considerable differences in cultures, economies and levels of business. The results of the correlation analysis showed that when the percentage of non-family managers in management positions increases, the percentage of a needed external assistance increases as well. At the same time, the number of conflicts within the company has decreased. The reduction in the number of conflicts in this case was due to previous conflicts between family members.

Similar topics have also been discussed in Kellermanns and Eddelston (2004), Kellermanns et al. (2008), Levesque and Minniti (2006) and Classen et al. (2014). In their 2008 research, the authors further developed the research of Zahra et al. (2004) and Zahra (2005), and worked with a sample (N = 232) of family businesses affiliated to two American universities in the northwest of the country. The study focused on executive directors of family and non-family businesses. Researchers distributed the questionnaire research to family members and evaluated their impact on the company. The results of the study showed a clear correlation between the performance of family businesses led by family leaders and non- family leaders.

Methodology

Data Collection and Sample Selection

Data for correlation analysis were primarily obtained by quantitative research (questionnaire survey) using CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interviewing) method, (Madlenak and Svadlenka, 2009). Respondents (population) are managers or owners of family businesses. They were sent emails including a cover letter and a hypertext link to the electronic questionnaire website. Businesses operate in the manufacturing industry (according to CZ NACE Group C) were broken down into micro, small and medium-sized enterprises according to Commission Regulation (EC) No 800/2008 (excluding independence).

Sampling was performed by random selection. The number of family enterprises (including micro, small and medium) was set to 4,396. Those family businesses in the Czech Republic were included in the sample. A response rate of 10 % (i. e. 440 questionnaires) was expected to be collected. However, only 292 questionnaires were collected. Out of these 292 questionnaires, 145 were family businesses, and the remaining were non-family businesses. The survey focused on both objective and subjective data. Most questions were chosen in the form of a closed question – ditochomical. The full form of these questions is in Section 4. Data processing was performed using statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics). The results were processed in the form of a correlation matrix with an explanation.

Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis is used to determine the linear dependence between quantities and variables (Ramsay, 2005). One commonly used indicator is the Pearson correlation coefficient r (3.1),

Outcomes

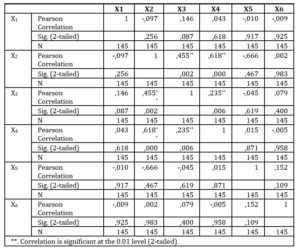

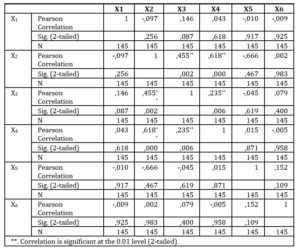

The influence of family representation on family businesses is examined by the following variables:

X1 – the share of family members in the ownership of the enterprise in percentage (%)

X2 – the number of members of the Board of Directors or Managing Directors

X3 -the number of family members from the Board of Directors or statutory representatives

X4 – the number of family members actively involved in the business

X5 – the number of family members inactively involved in the business

X6 – the number of family members who are not interested in family business

The results of the correlation analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Correlation Matrix

Source: own calculations

The results show that the most significant dependence is between X4 and X2. In other words, the number of members of the board of directors and the number of family members actively involved in the business are interdependent variables. The most significant indirect dependence is between X5 and X2 (i.e. the number of family members not actively involved in business and the number of members of the board of directors). There is also a significant correlation between the number of board members X2 and the number of family members on the board X3. In other cases, only slight or near zero dependencies were found.

For example, slight dependencies were found in X1 and X2. This may be due to the fact that the size of the business does not correspond to the number of members of the board of directors of family members. In this case, shares may be held by non-family members who are one of the members of directors or even executive directors of family businesses. Shares are then diversified in both family representatives and non – family members who are working in the company.

There is almost no dependence between the variables X4 and X6, or X2 and X6. In case of X4 and X6 variables, this may be due to the difficulty of determining how many family members are actively involved in the business at any given time. Reluctance or lack of interest in one’s own family business often leads to a crisis. In the event of a company crisis, companies might choose to hire employees from outside the company. This decision may even be fatal because someone who is not a member of a family business company will not be able to immediately solve the issue. Instead of this solution, companies should focus on handling the problem on their own. This may be an additional topic for elaboration and for conducting the research.

The positive relationship between the studied variables was proved, but not entirely. In a family business, there are interdependent variables relating to board members and family members who are actively involved in the business. It is desirable for a family business to have its family members work at all levels of the business. Another important element is the cooperation between employees and the top management. If family members in a family business cooperate with no contradictions, the business can be successful. On the other hand, a negative dependence was found in X3 and X5. The reluctance of employees outside the family to support the company management is often detrimental to the corporate environment and the company is forced to gradually replace family employees with non-family employees. It follows from the above that a successful family business should be made up of cooperating family members.

Conclusion

To conclude, the study evaluates the influence of family representation in a family business by using the statistical method of correlation analysis. According to the findings, different dependencies between the variables examined were found. The correlation between the number of directors (X2) and the number of family members actively involved in family business (X5) was the highest. In some cases, however, the dependence has also been refuted, as evidenced by the relationships between X4 and X6, or X2 and X6, for example. They have zero dependence.

The main findings in this research are, to some extent, consistent with those of Schulz et al. (2001), Parasuraman et al. (1996) and Anderson and Reed, (2003). On the contrary, the conclusion of the study by Olson et al. (2003) differs from the findings in this study. For example, the influence of employees who have been selected among non- family member workers may be the subject of further research. The article mentioned the negative influence of these employees several times. It would certainly be interesting to compare it with other EU countries on how they perceive this issue in their family businesses. Other research opportunities are, for example, in areas of corporate social responsibility, crisis management or social managerial etiquette.

The family businesses in the Czech Republic are still sustainable. However, the research on family businesses in the Czech Republic is overlooked. Extensive research has been carried out in some universities, such as TU Liberec, Brno University of Technology and University of Economics, Prague, (Machek and Hnilica, 2015). Some impact surveys are also carried out by the Association of Small and Medium Enterprises. Nevertheless, the research does not correspond to the result on a global scale. The presented research aims to help fill the research gap in the Czech Republic as mentioned above.

Acknowledgment

“This article was prepared as a part of the SGS project at the Faculty of Economics, VŠB-TU Ostrava, project number: SP2019 / 7“.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Anderson, R. and Reeb, D. (2003), ‘Founding‐Family Ownership, Corporate Diversification, and Firm Leverage,’ The Journal of Law & Economics 46(2), 653-684.

- Aronoff, C. and Ward, J. (2016) Family Business Governance: Maximizing Family and Business Potential.New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Astrachan, JH., Klein, SB. and Smyrnios, KX. (2002), ‘The F-PEC Scale of Family Influence: A Proposalfor Solving the Family Business Definition Problem’, Family Business Review15(1), 45–58.

- Astrachan, JH., and Shanker, MC. (2003), ‘Family Businesses Contribution to the U.S.Economy: A CloserLook, ‘Family Business Review 16(3), 211–219.

- Bloom, N. and Van Reenen, J. (2007), ‘Measuring and Explaining Management Practices Across Firms and Countries,’The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(4), 1351-1408.

- Botero, I., Cruz, C., DeMassis, A. and Nordqvist, M. (2015), ‘Family Business Research in the European Context’, European Journalof International Management 9(2), 139-159.

- Carr, C. and Bateman S. (2009), ‘International Strategy Configurations of the World’s Top Family Firms, ‘Management International Review 49, 733–758.

- Chittoor, R.and Das, R. (2007), ‘Professionalization of Management and Succession Performance?

- A Vital Linkage’,Family Buiness Review 20, 65–79.

- Chiu, C H. (1998) Small Family Business in Hong Kong: Accumulation and Accommodation. Chinese University Press.

- Classen, N., Carree, M., Van Gils, A. and Peters, B. (2014), ‘Innovation in Family and Non-family SMEs: An Exploratory Analysis’,Small Business Economic, 42(3), 595-609.

- Déniz, MDLCD. and Suárez, MKC. (2005), ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and Family Business in Spain’, Journalof Business Ethics56(1), 27-41.

- Doney, P., Cannon, J. and Mullen, M. (1998), ‘Understandingthe Influence of National Culture on the Development of Trust’, The Academy of Management Review23(3), 601-620.

- Evropský parlament (2015), Usnesení Evropského parlamentu ze dne 8. září 2015 o rodinných podnicích v Evropě (2014/221(INI).

- Fernández, Z. and Nieto, MJ. (2005). ‘International Strategy of Small and Medium-sized Family Business: SomeInfluential Factors’, Family Business Review 18, 77–89.

- Frank, H., Kessler, A., Rusch, T., Suess‐Reyes, J. and Weismeier‐Sammer, D. (2017), ‘Capturing the Familiness of Family Businesses: Development of the Family Influence Familiness Scale (Fifs)’, Entrepreneurship: Theory 41, 709-742.

- Goehler, A. W. (1993) Der Erfolg Grosser Familienunternehmenim Fortgeschittenen Marktebenszyklus, Dissertation, HSG St. Gallen.

- Gomez-Mejia, LR., Makri, M. and M. Larraza-Kintana (2010), ‘Diversification Decisions in Family-Controlled Firms,’ Journal of Management Studies 47, 223–252.

- Graves, C. and Thomas J. (2006), ‘Internationalization of Australian Family Businesses: A Managerial Capabilities Perspective,’ Family Business Review 19, 207–224.

- Habbershon, T. G., Williams, M. and Macmillan, I. C. (2003), ‘A Unified Systems Perspective of Family Firm Performance,’ Journal of Business Venturin 18(4), 451-465.

- Hnilica, J. and Machek, O. (2015). ‘Toward a measurable definition of family business: surname matching and its application in the Czech republic,’ International Advances in EconomicResearch 21(1), 119-120.

- Holt, DT., Rutherford, MW. and Kuratko, DF. (2010), ‘Advancing the Field of Family Business Research: Further Testing the Measurement Properties of the F-PEC,’Family Business Review 23(1), 76–88.

- Kalls, S. and Probst, S. (2013) Familienunternehmen: gesellschafts – undzivilrechtliche Fragen.Wien, Manzsche Verlagsund Universitätsbuchhandlung.

- Kellermanns, FW. and Eddleston, KA. (2004), ‘Feuding Families: When Conflict Does a Family Firm Good,’ Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 28(3), 209–228.

- Kellermanns, FW., Eddleston, K., Barnett, T. and Pearson, A. (2008), ‘An Exploratory Study of Family Member Characteristics and Involvement: Effects on Entrepreneurial Behavior in the Family Firm,’ Family Business Review 21(1), 1–14.

- Klein, SB., Astrachan, JH. and Smyrnios, KX. (2005), ‘The F–PEC Scale of Family Influence: Construction, Validation, and Further Implication for Theory,’Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29(3), 321–339.

- Kontinen, T. and OjalaA. (2010), ‘The Internationalization of Family Businesses: A Review of Extant Research,’ Journal of Family Business Strategy 1, 97–107.

- Krajňák, M. (2018) ‘Selected Aspects of Personal Income Tax in the Czech Republic,’ Journal of Applied Economic Sciences, 13(5), 1429-1439.

- Levesque, M. and Minniti, M. (2006), ‘The Effect of Aging on Entrepreneurial Behavior,’ Journalof Business Venturing 21, 177–194.

- Maloni, MJ., Hiatt, MS. and Astrachan, JH. (2017), ‘Supply Management and Family Business: A Review and Call For Research,’ Purch. Supply Management 23(2), 123–136.

- Madlenak, R. and Svadlenka, L. (2009), ‘Acceptanceof Internet Advertising by Users in the Czech Republic,’ E & M ekonomie a management 12(1), 98-107.

- Masulis, R., Pham, P. and Zein, J. (2011), ‘Family Business Groupsaround the World: Financing Advantages, Control Motivations, and Organizational Choices,’The Review of Financial Studies 24(11), 3556-3600.

- Mccormick, DP. (2016) Family Inc.: Using Business Principles to MaximizeYour Family’sWealth. Hoboken, USA: Wiley.

- Merino, F., Monreal-Pérez, J. and Sánchez-Marín, G. (2014), ‘Family SMEs Internationalization: Disentangling the Influence of Familiness on Spanish Firms Export Activity,’ Journal of Small Business Management,53(4), 1164-1184.

- Moores, K. (2009) ‘Paradigms and Theory Building in theDomainof Business Families,’Family Business Review, 22(2), 167–180.

- Nacht, J. (2018) Champions and Champion Families: Developing Family Leaders to Sustain the Family Enterprise. Chicago: Family Business Consulting Group.

- Olson, PD., Zuiker, VS., Danes, SM., Stafford, K., Heck, RK. and Duncan, K. A. (2003), ‘The Impact of the Family and the Business on Family Business Sustainability, ‘Journalof Business Venturing, 18(5), 639-666.

- Ramsay, JO. (2005) Functional data analysis. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Randová, K., Krajňák, M. and Friedrich, V. (2013), ‘Impact of Reduced VAT Rate on the Behavior of the Labour Intensive Services Suppliers,’ International Journal of Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences,7(5), 508-518.

- Rivers, W. (2003). Family-OwnedBusiness Planning Done Wrong. Family Business Institute. [Online], [Retrieved August 23, 2019], https://www.familybusinessinstitute.com/family-owned-business-planning-done-wrong/

- Rutherford, MW., Kuratko, DF. and Holt, DT. (2008), ‘Examining the Link Between “Familiness” and Performance: Canthe F–PEC Untanglethe Family Business Theory Jungle?’Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32(6), 1089–1109.

- Sáenz González, J. and García-Meca, E. (2014), ‘Does Corporate Governance Influence Earnings Management in Latin American Markets?’ Journal of Business Ethics 121(3), 419 – 440.

- Schulze, W., Lubatkin, M., Dino, R. and Buchholtz, A. (2001), ‘Agency Relationships in Family Firms: Theory and Evidence,’ Organization Science 12(2), 99-116.

- Sharma, P., Chrisman, JJ. and Chua, JH. (1997), ‘Strategic Management of the Family Business; Past Research and Future Challenges,’ Family Business Review 10(1), 1–34.

- Sonfield, MC. and Lussier, RN. (2004), ‘First-, Second – and Third-GenerationFamilyFirms: A Comparison,’ Family Business Review 17(3), 189–202.

- Sonfield, MC. and Lussier, RN. (2005), ‘Family Business Ownership and Management: A Gender Comparison,’ Journal of Small Business Strategy 15(2), 59–76.

- Sonfield, MC., Lussier, RN., Pfeifer, S., Manikutty, S., Maherault, L. and Verdier, L. (2005), ‘ A Cross National Investigation of First-generation, Second-generation, and Third-generation Family Businesses: A Four Country ANOVA,’ Journal of Small Business Strategy 16(1), 9–26.

- Sonfield, MC. and Lussier, RN. (2009), ‘Non-Family-Members in the Family Business Management Team: A Multinational Investigation,’International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 5(4), 395-415.

- Parasuraman, S., Purohit, YS., Godshalk, VM. and Beutell, NJ. (1996), ‘Work and Family Variables, Entrepreneurial Career Success, and Psychological Well-being,’ Journal of vocational behavior 48(3), 275-300.

- Pindado, J., Requejo, I. and de la Torre, C. (2012), ‘Do FamilyFirms Use Dividend Policy as a Governance Mechanism? Evidence Fromthe Euro Zone.’ CorporateGovernance: An International Review 20(5), 413-431.

- Tagiuri, R. and Davis, JA. (1996), ‘BivalentAttributesoftheFamilyFirm,’ Family Business Review 9(2), 199-208.

- Zahra, SA., Hayton, JC. and Salvato, C. (2004), ‘Entrepreneurship in Family vs. Non–FamilyFirms: A Resource–Based Analysis of the Effect of Organizational Culture,’EntrepreneurshipTheory and Practice 28(4), 363–381.

- Zahra, SA. (2005) ‘Entrepreneurial Risk Taking in FamilyFirms,’Family Business Review, 18(1), 23–40.