Introduction

Economic immigrants play an increasingly important role in balancing the proportion of employment in the labour market in the European Union countries. Most of the European Union countries have undergone a migration transformation in the last two decades, which was forced by the change in the economic conditions of their development (Górny et al. 2010; Janicka, Kaczmarczyk 2010; Duszczyk et al. 2013). Functioning in a highly competitive global market has resulted in a transition from the phase of mass emigration and negative migration balance, to the phase of increased supply for foreign labour and a positive migration balance. The necessity to cope with competition on the world market in the conditions of demographic stagnation and ageing of the society as well as a clear segmentation of the labour market created clear conditions for the influx of foreigners to European labour markets. For years, Poland was a country of emigration, not immigration. The percentage of foreigners coming to Poland and settling here was small – 0.2% in 2007, 0.3% of the population in 2015, less than 0.1% in 2020 which placed the country in one of the last places in the EU when it comes to the share of immigrants in the total population (Eurostat). Immigration to Poland was not only limited in number but was also a derivative of the influx only from a few countries, mainly Ukraine and Vietnam, additionally mainly for a short time (Górny, Toruńczyk-Ruiz 2011). The migration situation in Poland began to change from the beginning of this decade, but the biggest breakthrough took place after 2014, especially due to mass immigration from Ukraine.

In recent years, Poland has become the most important destination country for Ukrainian migrants. This was due to many unfavourable push factors on the Ukrainian side and overlapping favourable pull factors on the Polish side. The increase in migration from Ukraine after 2014 was due to the difficult political situation related to Russia’s aggression and its socio-economic consequences. The main reason for the increased influx of Ukrainian migrants to Poland after 2014 was a significant increase in the difference in wages between Poland and Ukraine, which is related to the deepening crisis in the quality of life (Tyrowicz 2017). Economic and political reasons related to Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine resulted in the reorientation of some Ukrainian migrants from the Russian market to Poland. Important factors attracting Ukrainian citizens to Poland are also: low travel costs, the ability to maintain family ties in Ukraine, extensive migration networks, as well as cultural proximity and linguistic similarities (Fedyuk, Kindler 2016; Górny, Kindler 2016). Therefore, the current wave of migration from Ukraine is also referred to as “local mobility” – a specific system of frequent and short-term economic arrivals to Poland while limiting expenses in the country of staying and concentrating one’s life activity in Ukraine, while migration in the classical sense assumes a permanent change of the centre of activity life.

This article aims to analyze the phenomenon of economic immigration in Poland and to try to answer the question of what challenges in the field of human resource management are caused by the increasing share of immigrants from Ukraine on the Polish labour market. The structure of the study was also subordinated to this goal – the considerations were set against the background of changes both in the procedural dimension of employing Ukrainians in Poland and the characteristics of the migration movement in this area. On this basis, a review will be made of the challenges posed by human resource management in the context of the intensifying migration movement.

The empirical base in the background of the considerations is statistical data available in national administrative registers. The method used is the desk research analysis.

Legal Conditions for Employing Foreigners In Poland

The policy of access to the Polish labour market can be divided into two key stages. The first (1990–2006) is the stage of the restrictive employment policy of foreigners in our country. The deterioration of the situation in the Polish labour market after the political transformation after 1989 resulted in numerous difficulties in accessing the labour market. The 1989 Employment Act made it compulsory to obtain a work permit, and the procedure was complicated and costly. The consequence of such a policy was a very small scale of legal employment of foreigners in Poland. From 1990 until 2006, approximately 233,000 jobs were issued, which means on average less than 14 thousand permits annually.

After Poland joined the EU structures in 2004, the situation changed. The scale of Poles leaving for other EU countries (especially GB) and the improvement of the situation on the domestic labour market resulted in an employment gap, especially in sectors such as construction, agriculture, and horticulture (Długosz, 2007). This contributed, i.e., to the initiation of a discussion on the wider opening of the Polish labour market to foreigners and the necessity to make changes to the policy pursued in this area. The result of the discussion was the gradual liberalization of regulations on the employment of foreigners. The process started in 2007 and is still ongoing. Perhaps in the next year, new procedures related to the employment of foreigners will be introduced, facilitating and even more liberalizing formal requirements, which will allow us to talk about the next stage of making the Polish labour market available to foreigners.

The increase in the number of Ukrainian migrants in Poland is also the result of changes in applicable law. Employment of foreigners is based on work permits issued by Voivods, seasonal work permits issued by Starosts at Poviat Labour Office and declarations on entrusting work to a foreigner, submitted by the employer at the Poviat Labour Office (Piotrowski, Organiściak-Krzykowska 2016).

In August 2006, the Minister of Labor and Social Policy issued an ordinance under which some foreigners were allowed to work legally without a permit in agriculture, for seasonal work. From 20 July 2007, these rules were extended to all sectors of the economy. According to them, citizens of Ukraine, Russia and Belarus, may work in Poland without a permit for 3 months during the next 6 months. The condition is to have a valid document entitled to enter the territory of Poland. (Ustawa o promocji zatrudnienia… 2004; CoUE 2001)

The employer is a party to the administrative procedure, which means that the employer who intends to employ a foreigner applies for a permit, not the foreigner himself. A work permit is issued for a specified period, not longer than 3 years, and may be extended. The Ordinance of the Minister of Labor and Social Policy of 29 January 2009 on the issue of a work permit for a foreigner specifies 5 types of permits [1], i.e., Type A – applies to foreigners performing work under a contract with an employer whose seat is located in Poland.

Under the regulation of December 8, 2017, a list of countries whose citizens

may apply for a seasonal work permit and a statement on entrusting work to a foreigner was defined. Ukraine is also on this list (Sejm RP 2017).

In January 2018, the categories of work performed based on a declaration on the intention to employ a foreigner were narrowed down (all work that is not seasonal, performed by the citizens of the six countries up to 6 months in the next 12 months).

At the same time, the key factor influencing the migration decisions of Ukrainian citizens was the decision to liberalize the visa system for Ukraine of May 11, 2017. On May 17, 2017, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU issued an appropriate regulation allowing citizens, among others from Ukraine, to stay in the Schengen area without a visa requirement for no more than 90 days every 180 days. These regulations have greatly facilitated the migration movement.

The stream of economic migrations from Ukraine to Poland

It is difficult to estimate the total number of foreigners staying in Poland, which is related, among others, to undocumented/unregistered immigration (Janicki 2016). Therefore, no reliable source of data exists that would allow for tracking the scale of immigration. Traditionally, scientists and experts base their research on administrative and statistical data sources, usually on residence permit data issued by the Office for Foreigners, work permits data and employers’ declarations on entrusting work to foreigners from the Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy, data on foreigners registered for permanent or temporary residence (PESEL register) from the Ministry of Digital Affairs, data on natural persons – foreigners from the Central Register of Entities – the National Register of Taxpayers, data on insured foreigners and their family members from the Polish Social Insurance Institution (ZUS) and its Central Register. It is worth noting that none of these sources provides reliable and comprehensive data.

As mentioned earlier, the condition for a foreigner who is not a citizen of an EU Member State to take up employment in Poland is to have a valid work permit. This rule has many exceptions, as it does not apply to people with a residence status that allows them to work without a permit (e.g., holders of a Pole’s Card). The situation is also different for students and graduates who can take up employment on the same terms as Poles. Changing the registration procedures of the so-called declarations on entrusting employment to a foreigner, also after the reform of January 2018, when it was decided to introduce seasonal work permits while leaving declarations in other (i.e., not strictly seasonal) sectors, created the basis for mass phenomenon immigration to Poland in the face of a very strong demand factor (labour supply deficits in the domestic labour market) and supply factor (migration potential in Ukraine). The statistical data confirm this unequivocally.

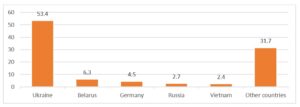

In 2020, according to Statistics Poland, 406.5 thousand work permits for foreigners were registered. It was 8.6% less than in 2019, but more than 6 times more than in 2015. This figure is reflected in the epidemic situation related to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Ukrainian citizens account for over 53% of foreigners registered in Poland (GUS 2020).

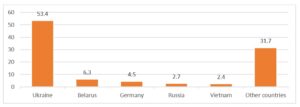

Figure 1: Valid residence permits (as of Jan 1, 2021)

Since 2012, the number of Ukrainians with work permits in Poland has increased almost tenfold. The data published by the Office for Foreigners allow for the characterization of foreigners present in the Polish labour market. Ukrainian citizens stay in Poland mainly for short-term visa-free travel or based on visas. However, more and more of them want to stay in the country for a longer period. This is evidenced by the growing number of applications for a residence permit and the group of people already in possession of such documents. In 2020, about 80 percent of Ukrainian citizens have a temporary residence permit, which may be valid for a maximum of 3 years. The vast majority of them are spent in connection with taking up a job – about 72.6 percent. The next most common reasons for staying in Poland are family issues – approx. 12 percent and education – approx. 5 percent.

According to data from Statistics Poland, in 2020, employers who obtained work permits for foreigners, conducted economic activity mainly in PKD sections: construction (23.5% share in the total number of permits), industrial processing (23.3%), administration and supporting activities (22.1%) as well as transport and warehouse management (17.8%). In 2020, in all voivodships, the total share of permits for the above-mentioned sections of the Polish Classification of Activities exceeded 78%.

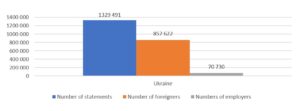

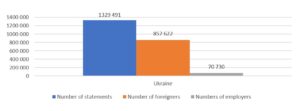

The second source of information on the scale of legal employment in Poland is the register of declarations on the employment of foreigners (MRPiPS 2018). A comparison of the growing dynamics of registered declarations with a stable number of work permits issued every year may prove that before introducing the possibility of employing foreigners based on declarations, the scale of unregistered employment of foreigners was very large. Illegal employment of Ukrainians appears to be gradually being replaced with legal employment, based on the declaration. Of course, it should be remembered that the submission of a declaration by the employer of the intention to employ a foreigner does not automatically mean that he or she will take up this job. The declaration instrument is used as the basis for applying for a visa to Poland, upon receipt of which a foreigner may work for another employer or be employed illegally. There is no information available on how many foreigners started work in Poland based on a registered declaration. The number and structure of registered declarations of intention to entrust work to a foreigner illustrate the advantage of Ukrainians over other nations. The number of declarations on entrusting work to a foreigner in 2020 exceeded 1.3 million and concerned over 8.5 thousand people.

Figure 2: Basic characteristics

(Author’s own work based on Ministry of Development data)

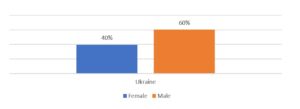

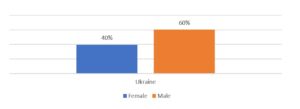

When analyzing the gender structure of migrants based on declarations on entrusting work to foreigners, a clear predominance of men can be noticed. The gender proportions in this area are similar to those recorded based on permits.

Figure 3. Gender

(Author’s own work based on Ministry of Development data)

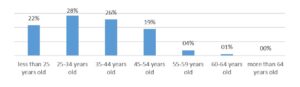

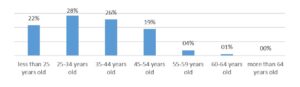

Economic Ukrainian migrants are mostly people of working age, the vast majority aged 25-44. With age, the proportion of economic migrants decreases – 1.4% of them are registered over 60 years of age.

Figure 4: Age of foreigners

(Author’s own work based on Ministry of Development data)

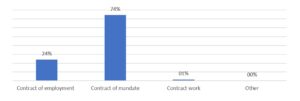

Most of the declarations on entrusting work to a foreigner registered in 2020 indicate the signing of mandate contracts with such persons. This is due to temporary employment and working conditions that are offered to Ukrainians.

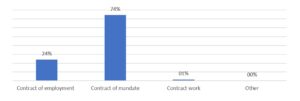

Figure 5: Form of a foreigners’ contract

(Author’s own work based on Ministry of Development data)

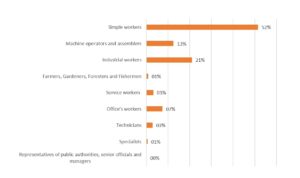

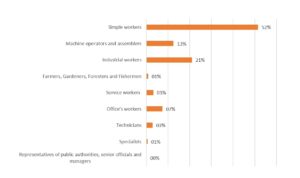

Figure 6: Professional groups

(Author’s own work based on Ministry of Development data)

Selected Challenges for Human Resource Management

Both the growing number of Ukrainians taking up employment in Poland and the changes in the structure of this group of employees undoubtedly contribute to the emergence of many challenges in the field of human resource management. Several key aspects characterizing economic migrations can be identified, which may translate into selected, various challenges for HRM.

(1) First, two different categories of economic migrants come to Poland to improve their financial situation and (a) intend to stay longer, or (b) count on quick earnings and return to their country of origin. Migration projections translate into the attitude to work itself, recruitment mechanisms, readiness to work in an oversized dimension, and different work culture. It can be assumed that people who want to stay longer in Poland in a slightly different, more rational way, plan their professional career, taking into account their competencies (acquired in the country of origin or the country of migration), willingness to work in a specific profession and the possibility of obtaining a specific remuneration. According to the data from the report carried out by the National Bank of Poland in 2020, it appears that a significant part of Ukrainian citizens working in Poland wants to stay in Poland for longer, 24% of them would like to stay permanently and another 14% would like to stay for at least 3 years. The percentage of people who do not have specific plans and who perceive trips to Poland only on the horizon of less than 1 year is relatively large, repeating the pattern of short-term migration. Taking into account the factors related to migration projects, it is important to plan the career paths of foreigners tailored to the needs of employers.

(2) Economic migrants are employed in particular in two categories of professions: low-paid and low-skilled and as highly skilled professionals. In many cases, the employment of specialists is associated with the certification of competencies, qualifications and the creation of other working conditions than in the case of workers performing simple work. Cooperation with employees who perform various types of work also requires the implementation of the postulates of the equal treatment policy. Equal treatment in employment means a lack of discrimination in any manner, direct or indirect, for any reason (Leenders et al. 2003).

(3) Type of document regulating the arrival and stay in Poland – people who come based on a visa and a biometric passport and can be employed for only 90 days are a problem for the employer related to relatively high employee turnover – in an average year, such an employee should be replaced almost four times. A relatively high rotation of employees is related to the effectiveness of the work performed, the need to take into account the time to train a new employee, obtain all the required qualifications, especially for employees of Ukrainian citizenship. Therefore, there is another challenge related to creating an incentive to stay longer in Poland by currently working with foreigners or offering them long-term, attractive employment (Trzeciakowski, Wąsowska 2018).

(4) The duration of the formal procedure for employing foreigners – depending on the type of documents, this period may be up to several months, which translates into the possibility of actual employment by a person (BCC 2017). One of the fundamental principles of administrative proceedings, essential and extremely important from the foreigner’s perspective, is that a matter should be processed quickly and efficiently by an institution. In practice, however, this rule is one of the most frequently violated by public administration bodies. Institutions very often fail to meet the deadlines provided for in the Code of Administrative Procedure, and sometimes do not inform the parties about the delay and its reasons and do not set a new deadline for dealing with the case.

Many research studies that highlight the lack of information in languages understood by foreigners and insufficient awareness among employers about the legal conditions of employment of foreigners are of prime importance. Employers and foreigners have difficulties understanding the regulations and procedures for obtaining individual permits. Information about individual permits can be found on official websites, usually only in Polish or in a few select foreign languages, and rarely updated. The limited number of helplines and consultation offices makes it impossible for employers and foreigners to obtain additional information, apart from the basic data published on the websites. The procedures for obtaining permits are also not transparent for employers, who have difficulties understanding which documents are necessary to obtain a permit. Additionally, they often lack information on how to make an appointment, are not aware of their obligations to inform the permit-issuing institution about the decisions concerning the foreigner’s permit, the termination of work by the foreigner, the change of conditions, the place of employment etc. Often, the lack of adequate information for the employer is related to the frequently changing regulations on employing foreigners.

(6) An issue conducive to the employment of foreigners in Poland in the field of human resource management is also the care for team cooperation, especially when they are of an international nature. Not without significance, apart from developing communication mechanisms, it is also the prevention and elimination of conflicts. It is also important for the smooth operation of companies to transfer skills and knowledge between migrants and natives, transfer skills, predispositions and knowledge from migrants to non-migrant colleagues, and by increasing the incentive for natives to increase their skills, which will allow companies to increase competition. In addition, the issues of leadership in task teams and the distribution of tasks are also worth noting. The key to efficient cooperation is interaction (Stankiewicz 2017).

Conclusions

Adequate employment is one way to integrate migrants into their host society, but despite the efforts made, employing migrants remains a challenge for employers, migrants and policymakers alike. In principle, Poland does not have a document that would define the assumptions of the national migration policy. All actions taken by the authorities in this area are ad hoc in nature and most often there is no prior analysis of the phenomenon and no deeper reflection on the consequences of planned actions. This applies to both the policy applied to economic migrants and the integration policy. In this context, shaping and diagnosing the condition of economic migrations becomes a test for researchers from various research disciplines. In Poland, the percentage of foreigners taking up employment (registered in various ways) has been growing for years. These migrations vary in terms of their motive, duration, form and projections about the future. For researchers and specialists dealing with the labour market, this outlines a multitude of scenarios of conduct and the best adaptation of solutions to the needs of both parties (employer and employee) and the entire social environment. The study identifies several challenges for the labour market, the consideration of which is to serve such management of human resources, which is aimed at a fuller use of the human capital of foreigners. Most of the challenges are related to the procedural requirements for employing foreigners – the changing legal situation, the lack of sufficient information, failure to take into account the specificity of working in international teams (and communication problems). The multiplicity of these challenges may discourage both employers and employees from legalizing employment. The solution may be to simplify the procedures announced by the Polish government. The draft of legal changes has been prepared by the Ministry of the Interior and Administration and assumes the simplification of the procedure for legalizing the stay of foreigners in Poland, especially in the case of combined residence and work permits, which are the most frequently granted type of temporary residence permits. The facilitations consist in resigning from the requirement to have a secure place of residence and the requirement to have a stable and regular source of income for the granting of a temporary residence and work permit. Instead, the foreigner is required to receive a salary not lower than the minimum wage, regardless of the working time and the type of legal relationship on which the foreigner performs work. Apart from the indicated challenges related to the efficient organization of work of foreigners in Poland, a very important criterion worth paying attention to is creating a social climate for foreigners. In this area, all integration activities, NGOs’ activities, and efforts to eliminate stereotypes, are worth attention. A good social climate for labour migrations may also contribute to achieving greater efficiency for employers – they can achieve employment stability and better ensure the transfer of competencies by employees. The presentation and analysis of the most important trends were the main starting point for identifying the most important challenges that Polish enterprises will have to face and above all the departments responsible for human resources management. The article discusses only selected issues, without trying to present them in an exhaustive, comprehensive manner.

Notes

[1] Type B – Issued to board members. Type C – issued to employees posted to work in Poland for a period exceeding 30 days in a calendar year to a branch or plant of a foreign entity, its subsidiary or an entity related by a long-term cooperation agreement with a foreign employer. Type D – issued to employees delegated to perform a temporary and occasional service (export service). Type E – applies to employees posted to Poland for a period exceeding 3 months within the next 6 months for a purpose other than that indicated in points 2-4.

References

- Briscoe, D. R., & Schuler, R. S. (2004). International human resource management: Policy and practice for the global enterprise. London: Routledge

- Business Centre Club (2017), ‘Brak rąk do pracy – usuńmy bariery w zatrudnianiu cudzoziemców’ [Online], Warszawa, [Accessed: October 15, 2021], http://www.lubelskie.pl/file/2017/12/Za%C5%82.- -Nr-4d.-Usu%C5%84my-bariery-w-zatrudnianiu-cudzoziemc%C3%B3w- -BCC.pdf

- Council Regulation (EC) No 539/2001 of 15 March 2001

listing the third countries whose nationals must be in possession of visas when crossing the external borders and those whose nationals are exempt from that requirement [Online], [accessed: September 23, 2021], https://eur-lex.europa.

eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32001R0539

- Długosz, Z. (2007), ‘Selected Aspects of Foreign Immigration to Poland at the Turn of the 20th/21st Century’, Bulletin of Geography, 7, 55–72.

- Duszczyk M., Góra M. and Kaczmarczyk P. (2013), ‘Costs and Benefits of Labour Mobility between the EU and the Eastern Partnership Countries – case of Poland’ [Online][accessed: October 15, 2021], http://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/89815/1/dp7664.pdf

- Fedyuk, O. and Kindler, M. (2016), ‘Migration of Ukrainians to the European Union: background and key issues’, [in:] O. Fedyuk, M. Kindler (eds.). Ukrainian migration to the European Union: Lessons from migration studies (s. 1-14), [Online] Cham: Springer International Publishing, [accessed October 15, 2021]; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41776-9_1

- Górny A., Grabowska-Lusińska I., Lesińska M. and Okólski M. (eds.) (2010), ‘Immigration to Poland: Policy, Employment, Integration’, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar;

- Górny A. and Toruńczyk-Ruiz, S. (2011), ‘Czy można połączyć ilość z jakością? Możliwości i bariery podejścia ilościowego w badaniach integracji migrantów w Polsce’, Studia Migracyjne – Przegląd Polonijny, Nr 2, 41-58.

- Górny A. and Kindler, M. (2016), ‘The temporary nature of Ukrainian migration: definitions, determinants and consequences’, [in:] Ukrainian Migration to the European Union: Lessons from migration studies, [Online] Springer International Publishing [accessed October 15, 21]

- Guo C., and Al Ariss, A. (2015), ‘Human resource management of international migrants: current theories and future research’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(10), 1287-1297.

- Janicka A. and Kaczmarczyk P. (2010), ‘Economic Consequences of the Inflow and the Sustainability of Migration’ [in:] A. Górny, I. Grabowska-Lusińska, M. Lesińska, M. Okólski (eds.), Immigration to Poland: Policy, Labour Market, Integration, Scholar, Warszawa;

- Janicki W. (2016), ‘Wiarygodność danych o migracjach ludności w niektórych państwach Europy Zachodniej’, Wiadomości Statystyczne, No. 3, pp. 80-92

- Leenders, R.T.A., Van Engelen and J.M., Kratzer, J. (2003), ‘Virtuality, communication, and new product team creativity: a social network perspective’, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 20(1), 69-92.

- MRPiPS (2018), Informacja o zatrudnieniu cudzoziemców w Polsce. Warszawa: MRPiPS, Departament Rynku Pracy

- Piotrowski M. and Organiściak-Krzykowska A. (2016), ‘Zatrudnienie cudzoziemców na polskim rynku pracy – aspekty popytowe i strukturalne’, Studia Prawno-Ekonomiczne, C

- Sejm Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej (2017), Ustawa z dnia 26 maja 2017 r. o promocji zatrudnienia i instytucjach rynku pracy, Dz. U. 2017, poz. 1065

- Stankiewicz K. (ed.) (2017), ‘Contemporary Issues and Challenges in Human Resource Management’ [Online], Gdańsk, [accessed: October 15, 2021], https://zie.pg.edu.pl/documents/10693/38995566/Contemporary%20Issues%20and%20Challenges.pdf,

- Trzeciakowski R. and Wąsowska K., Analiza 7/2018: ‘Potrzebujemy imigrantów. Jak zatrzymać ukraińskich pracowników w Polsce?, lipiec 2018’, [Online] [accessed October 15, 2021], https://for.org.pl/ pl/a/6100,analiza-7/2018-potrzebujmy-imigrantow-jak-zatrzymac-ukrainskich-pracownikow-w-polsce

- Tyrowicz J. (2017), ‘Znaczenie imigracji zarobkowej dla gospodarki Polski’, Zeszyt mbank-CASE 149, Warszawa: CASE

- Ustawa o promocji zatrudnienia i instytucjach rynku pracy (2004), Dz.U. 2018 r. poz. 1265; Council of the European Union (2001)

- Zezwolenia na pracę cudzoziemców w Polsce w 2020 r. (2020) [Online], GUS, Warszawa, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/zezwolenia-na-prace-cudzoziemcow-w-2020-roku,18,4.html [accessed at October 15, 2021]