Introduction

Human well-being is one of the most important categories constituting the modern society. Its structure indicates complexity and multidimensionality of this phenomenon in biological, psychical, social and economical terms. Therefore, it is the subject of studies of a lot of scientific disciplines – sociology, psychology, economics, medicine or environmental engineering. Taking into account the scientific interests of the authors of the study, the deliberations will have special context in the perspective of sociology, economics and environmental engineering. It is so due to the fact that the human well-being category is determined by social relations, consumer behaviours and state of natural environment, which determine health, as well as a moderate level of economic welfare. Sciences combining various scientific disciplines, such as: economic sociology and economic psychology, will constitute an important point of reference. In this context, new categories of intangible goods significantly affecting human well-being, such as: health, happiness, satisfying social relations, friendly natural environment exceeding the conventional values and tangible goods, emerge. The pandemic, having global reach since 2020, has irreversibly changed the human well-being category. Satisfaction with life becomes the key value of human well-being. Therefore, in the research, the results of which will be published herein, we will focus not only on the issues determining the categories of human well-being but also on the factors that have been deteriorating it in recent years, including in particular the pandemic. We are dealing with the situation in which, on the one hand, unprecedented development of technologies, science and rationality has taken place, and on the other hand, we have understood the complicated dimension of fragility of human life and threats to it. The pandemic experiences of the 20th and 21st century indicate that unhealthy and bad living conditions accompany the spread of the pandemic. International experts state that the present SARS COVID-19 pandemic will stay with us for a couple of years. The researchers say that implications of the pandemic for the present societies, taking into consideration the ultimate demographic and economic consequences thereof, are unpredictable [1]. The aim of the article will be the determination of the lifestyle of the Poles in the pandemic as well as comparison of their biological, social, psychical and economic well-being before and during the pandemic. It is connected with the fact that in spite of the previous experiences relating to dangerous SARS-CoV, emergence of COVID-19 surprised the world and undoubtedly caused global public health crisis affecting all aspects of human life [4].

Factors Affecting Human Well-Being

The well-being category is usually referred to as the rate of adaptation to difficult and crisis situations. Therefore, it may constitute the subject of analysis in the conditions of the emerging epidemic threats in a particular way [14]. Development of positive psychology started at the end of the 90’s of the 20th century and has contributed to the search for deeper understanding of the concept of well-being and satisfaction with life [16]. The factors affecting the well-being category lying not only in human actions but also in the environment have been expanded. Therefore, well-being is not only a new research programme but criticism in understanding of both individual and social development [3]. In creating of the well-being category, for instance like a health, very important is to reduce a feeling of discomfort but an approach in this area is still evolves.[7]

Due to quite frequent synonymous treatment of the category of well-being and welfare in social life practice, the respondents were to differentiate between these terms in the first part of the survey. The majority of them interpreted them correctly, treating well-being as a mental state and a measure of satisfaction with life while welfare – as the standard of living. Also, dichotomous approaches to these terms connected with association of well-being with intangible values and of welfare with tangible values and the level of satisfaction of vital needs appeared. In our own research, the factors of human well-being taking into account the individual development measures, such as: proper level of nutrition, proper length of sleep, health prevention, financial stability, good housing conditions, but also taking into consideration well-being of others through proper family relations, work relations, proper attitude towards animals, but also observance of the principles of environmental protection, were proposed. In order to achieve proper level of feeling and to function well, the challenges and tasks resulting from functioning in the social and natural environment should be risen to [15].

The discussion determined above indicates that the approach to human well-being should be analysed on various levels in a multi-dimensional way. Therefore, focusing solely on individual or external perspective is in the opinion of the researchers limited and could omit some important issues of the dynamics of this phenomenon [5]. Diagnostic poll based on quantitative research methodology with the use of CAVI technique based on online survey technique was applied, N=672 respondents from the area of the entire Poland. The research was conducted by the students of economic sociology of the University of Wrocław under the direction of the author within research workshops. In our research, we propose a holistic approach to human well-being, using the interdisciplinary knowledge relying not only on an individualistic psychological approach but also on a social perspective taking into consideration various levels of social interactions, an economic perspective based on consumer behaviour theory and designing of ‘I’ in consumption as well as environmental engineering building human well-being through friendly environment [11]. Human well-being is referred to the ecosystem theory assuming that human is an integral part thereof, so they have to live in harmony therewith, which becomes a guarantee for access to clean air, water and soil and also lowers the risk of occurrence of natural catastrophes and disasters destroying humans’ safety and lifetime possessions [12].

Consumption Behaviours Deteriorating Human Well-Being

Human well-being depends on the level of consumption which significantly affects not only the biological but also the mental health of a human [10]. In this part of the research, we also designed a holistic look on human well-being in the perspective of consumer behaviours, referring them not only to the sphere of individual consumption and bad eating habits deteriorating human life, such as: eating animal fats, drinking alcohol or smoking cigarettes, but also to care about natural environment through refraining from the use of plastic packaging or from heating with coal; see Table1.

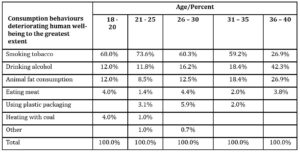

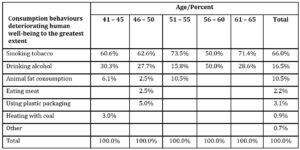

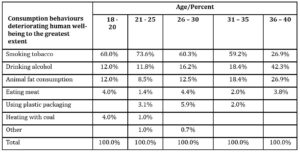

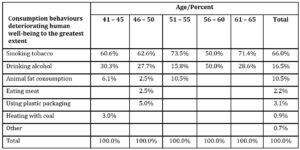

Table 1a. Consumption behaviours deteriorating human well-being to the greatest extent depending on the age* of respondents.

Table 1b. Consumption behaviours deteriorating human well-being to the greatest extent depending on the age* of respondents.

Source: Authors’ own research

*% of the respondent’s age group

SPSS statistics taking into account age category as an independent variable was used in the analyses. The respondents stated that human well-being deteriorated to the greatest extent due to smoking cigarettes (66.0% of the respondents, N=672) and drinking alcohol (16.5%) as well as animal fat consumption (10.5%). They attached smaller weight to environmental protection connected with heating with coal (0.9 %), using plastic packaging (3.1%) or eating meat (2.2%). It results from the cross table presented above that deterioration of human well-being due to drinking alcohol was indicated the most often by the respondents at the mature age of 56 – 60 (50% of the respondents) and at the middle age of 36 – 40 (42.3% of the respondents). Similarly, animal fat consumption was indicated by the respondents at the age of 36 – 40 (26.9%), 31 – 35 (18.4%) and 51 – 55 (105%). On the other hand, the issues connected with environmental protection through eating meat were indicated the most frequently by young respondents at the age of 26 – 30 (4.4%) and 18 – 20 (4%). In turn, the use of plastic packaging connecting the categories of environmental protection and human well-being was indicated the most often by young respondents at the age of 26 – 30 (5.9%) and at the mature age of 46 – 50 (5.0%), while the issues connected with heating with coal – by the respondents at the age of 18 – 20 (4%) and 41 – 45 (3%). Pearson’s chi-square of dependency of consumption behaviours deteriorating human well-being on respondent age category is 95.127; the critical value of chi-square distribution read from the table, with asymptotic significance (2-sided) 0.003 and conformity factor df=60, amounts to 83.2977; so the set research hypothesis relating to dependency of the consumption behaviours deteriorating human well-being was confirmed.

Lifestyle during the Pandemic

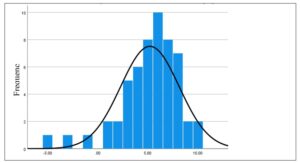

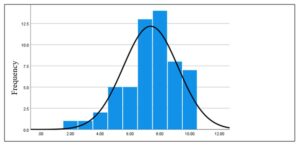

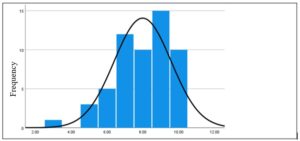

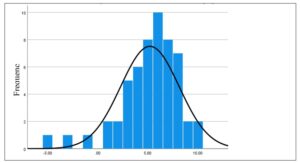

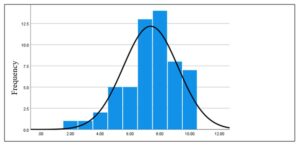

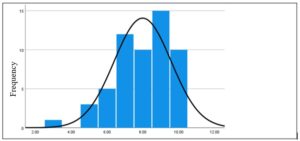

It is lifestyle that has the greatest impact among all factors affecting human health condition and thus, human well-being [8]. Lifestyle changes over throughout life. These changes are connected with age, sex, personality features, health condition, performed social roles and changing environmental factors [6]. The pandemic has changed the lifestyle of millions of people all over the world. This is why we designed the assessment of the lifestyle of the respondents during the pandemic after its first wave (March 2020) in our own research. The respondents assessed it on dichotomous scales of pro-health style from 1 to 10 and of anti-health style from -10 to 0. The results are presented by the histogram below – see Figure 2. It results from the research that the respondents assessed their lifestyle during the pandemic as averagely pro-health one with the dominant scale 6 (17.9%), then 5 and 7 (14.3% each) and 8 (12.5%). Only 7.2% of the respondents considered it as very pro-health one on scale 9 and 10. On the other hand, 7.2 % of the respondents considered it as anti-health on moderately negative scales from -5 to -1.

Figure 2. Assessment of the level of pro-healthiness of lifestyle during the pandemic among the respondents on a scale from -10 to 10.

Source: Authors’ own research

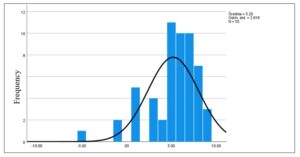

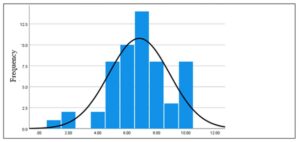

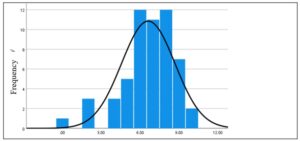

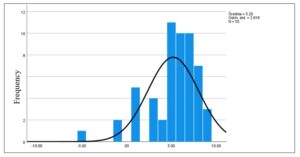

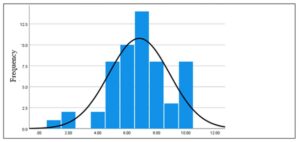

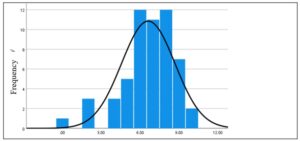

The holistic concept of the research resulted in the fact that we were researching lifestyle not only in individual terms but also in a wider sense, in terms of ecosystem. This is why the respondents assessed their lifestyle during the pandemic on a scale from 1 to 10 as eco-friendly and on a scale from -10 to 0 as non-eco-friendly. Assessment of this dimension of lifestyle was worse than the results relating to the level of pro-healthiness of lifestyle. It is so due to the fact that the dominant assessment scale was 5, which was chosen by 19.6% of the respondents, then it was 6 and 7 – chosen by 17.9% of the respondents each, with no 10 assessment and with the top assessment 9, indicated by 5.4% of the respondents. The lowest assessments on the scale of the non-eco-friendly style were within the range from -5 to -1 and were selected by 5.4% of the respondents, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Assessment of the level of eco-friendliness of lifestyle during the pandemic among the respondents on a scale from -10 to 10.

Source: Authors’ own research

Biological, Social, Psychical and Economic Well-Being during the Pandemic

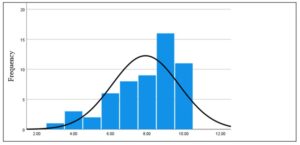

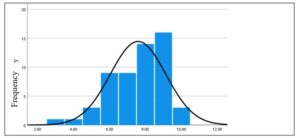

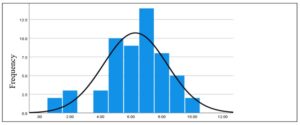

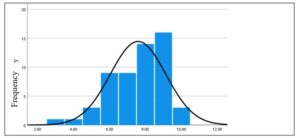

The individual dimensions of biological, social, psychical and economic well-being were researched before the pandemic and during the pandemic on a similar scale of disparities as in case of assessment of lifestyle among the respondents from -10 to 10; see Figure 4. Before the pandemic, the respondents assessed their biological well-being on scale 8 (25.0% of the respondents) and 7 (23.2%) and next, on scale 9 (14.3%) and 10 (12.5%).

Figure 4. Assessment of biological well-being among the respondents before the pandemic

Source: Authors’ own research

On the other hand, during the pandemic, after the first wave (March 2020), the dominant assessment dropped from 8 (25.0%) to 7 (25.0%) and from 9 (14.3%) to 6 (17.9%); see Figure 5

Figure 5. Assessment of biological well-being among the respondents during the pandemic, after the first wave in March 2020.

Source: Authors’ own research

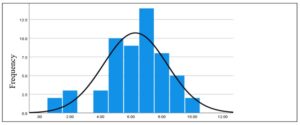

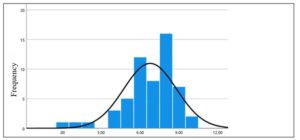

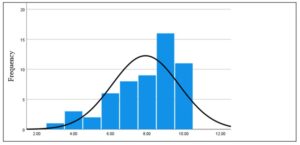

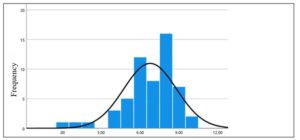

The next researched level was social well-being. It was assessed highly before the pandemic. The dominant scales were 9 (28.6% of the respondents) and 10 (19.6%) and next, 8 (16.1%) and 7 (14.3%); see Figure 6.

Figure 6. Assessment of social well-being before the pandemic.

Source: Authors’ own research

On the other hand, after the first wave of the pandemic, social well-being dropped significantly, which is shown by the assessments of the respondents from the dominant scale 9 (28.6%) and 10 (19.6%) to prevailing assessment 7 (25.0%) and 5 (17.9%) and next 6 (16.1%); see Figure 7.

Figure 7. Assessment of social well-being after the first wave of the pandemic in March 2020.

Source: Authors’ own research

Before the pandemic, the level of psychical well-being was mainly on scale 9 (26.8% of the respondents) and 7 (21.4%) and next 10 (17.9%) and 8 (17.9%); see Figure 8.

Figure 8. Assessment of psychical well-being before the pandemic.

Source: Authors’ own research

On the other hand, after the first wave, it decreased from the dominant assessment 9 (26.8% of the responses) and 7 (21.4%) to 8 (21.4%) and 6 (21.4%) and next 7 (19.6%) and 9 (12.5%); see Figure 9.

Figure 9. Assessment of psychical well-being after the first wave of the pandemic in March 2020.

Source: Authors’ own research

Economic well-being of the respondents before the pandemic was assessed mainly on scale 9 (28.6% of the respondents) and 8 (25.0%) and next 6 and 7 (16.1% each); see Figure 10.

Figure 10. Assessment of economic well-being before the pandemic.

Source: Authors’ own research

On the other hand, after the first wave of the pandemic, it decreased from the dominant assessment 9 (28.6%) and 8 (25.0%) to the dominant assessment 8 (28.6%) and 6 (21.4%) and next 7 (14.3%); see Figure 9.

Figure 11. Assessment of economic well-being after the first wave of the pandemic in March 2020.

Source: Authors’ own research

Conclusion

It results from our research that the level of well-being decreased in all dimensions – in biological, social, psychical and economic one – after the first wave of the pandemic. However, it is social and psychical well-being that decreased the most, which resulted from the general isolation and change of lifestyle during the lockdown. The dominant high scales of assessments for social well-being before the pandemic dropped during the pandemic to medium and low level, similarly to the assessments for psychical well-being. In the research performed in 194 cities in China in January and February 2020 with the use of an online survey, 53.8% of the respondents assessed the psychological effects of the outbreak of the pandemic as moderate or severe [17]. In similar Spanish research, it was stated that the outbreak of the pandemic had significant impact on psychological well-being, increasing psychical disorder morbidity rate in the population. It results from the research conducted in March 2020 with the use of an online questionnaire method that the frequency of depression symptoms was higher than in China but lower than in the research conducted during SARS epidemic in Hong Kong [9]. During COVID-19 pandemic, due to animal origin of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, consumption started to be under unprecedented pressure due to the need to apply sanitary regime measures in the scope of various forms of consumer behaviours. It results from our own research that the respondents decide that smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol or eating animal fats may deteriorate their well-being more often than caring about natural environment through limitation of the use of plastic or heating with coal, while the dependencies are different depending on the age. Older and more mature respondents more frequently associate the behaviours deteriorating well-being with the traditional forms of consumption than younger respondents who contest these behaviours in terms of changes of the eco-system. The results of our research fit in the trend of the international studies and hypotheses relating to dependency of human well-being on the environmental conditions. More and more research relates to the relationship between the environment and mortality rate, in particular on urbanised areas [13]. It results from Italian studies that long-term exposure to polluted air leads to chronic infectious stimulus even in young and healthy persons [2]. It is also confirmed by low assessments of the level of lifestyle in the scope of pro-health behaviours as well as eco-friendly behaviours of Polish consumers during the pandemic. This research indicates the need to redefine the measures of human well-being in the new conditions which the human and the global society will be functioning in after the pandemic especially in aspect of economics [18].

References

- Alfani, G. (2020), Pandemics and Asymmetric Shocks: Evidence from the History of Plague in Europe and the Mediterranean. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341767192_Pandemics_and_Asymmetric_Shocks_Evidence_from_the_History_of_Plague_in_Europe_and_the_Mediterranean/link/5ed2c0ad92851c9c5e6bf0d2/download (23/08/2021).

- Conticini, E., Frediani, B. and Caro, D. (2020), ‘Canatmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy?’, Environmental Pollution 261:1114465, in:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340431558_Can_atmospheric_pollution_be_considered_a_co-factor_in_extremely_high_level_of_SARS-CoV-2_lethality_in_Northern_Italy (17/09/2021).

- Diener, E. (2009). Positive psychology: Past, present, and future. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed.,). Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 7-12.

- Drop, D., Janiszewska, M. and Drop, K. (2021), ‘Covid-19 jako globalny problem zdrowia publicznego’, Polish Journal of Public Health, 129 (4), 121.

- Fisher, A. T. (2013), Understanding Well-Being in Multi-Levels: A review, November 2013, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260894839_Understanding_Well-Being_in_Multi-Levels_A_review (24/08/2021).

- Green, L. and Kreuter, M. (2005), ‘Health program planning’’: An educational and ecological approach. New York; McGraw-Hill.

- Keyes, C. L. M., and Waterman, M. B. (2003), ‘Dimensions of well-being and mental health in adulthood’.’ In B. M. H. (Ed.), Well-being: Positive development across the life course Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Lalonde, M. (2021), ‘New Perspective on the Health of Canadians’, https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/pdf/perspecteng. pdf (17/09/2021).

- Lee, S., Chan, L.Y., Chau A. M., Kwok K.P., Kleinman A.,( 2005), ‘The experience of SARS-related stigma at Amoy Gardens’, Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:2038-46, in: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953605001760?via%3Dihub (17/09/2021).

- Patrzałek, W., (2019), ‘ Motywy, cele, funkcje’, Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu.

- Patrzałek, W., (2020), ‘Inwestycyjny wymiar konsumpcji a zrównoważony rozwój’, in Inwestycyjny wymiar konsumpcji. Istota, formy, znaczenie, ed. Olejniczuk-Merta A., Noga A., Warsaw: Poltext Sp. z o. o.

- Preston, S. H., (1996), ‘American Longevity, Past, Present, and Future’. Syracuse University. Maxwell School Center for Policy Research Policy Brief 7/1996; D. M. Cutler, G. Miller, (2005), The Role of Public Health Improvements in Health Advances: The Twentieth-Century United States, Demography 42(1): 1–22.

- Reid, W. V., Mooney H. A., Capistrano D., l In. ‘Ecosystems and human well-being – Synthesis’: A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/ecosystems-and-human-well-being-synthesis-a-report-of-the-millenn/fingerprints/ (24/08/2021).

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). ‘Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being.’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069-1081.

- Ryff, C.D. (2017), ‘Eudaimonic well-being, inequality, and health: Recent findings and future directions.’ International Review of Economic, 64, 159-178.

- Seligman, M.E.P. (2011). ‘Pełnia życia. Nowe spojrzenie na kwestię szczęścia i dobrego życia.’ Poznań: Media Rodzina.

- Wang, C., Pan R., Wan X, Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C. S., Ho R. C., (2020), ‘Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China, in https://europepmc.org/article/med/32155789 (17/09/2021).

- Manta, A.M. (2020), ‘COVID-19 Pandemic – A Permanent Socio-Economic Change?’, Proceedings of the 35th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), Seville, Spain, Apr 01-02, 16462-16471.