Introduction

Education is a resource in danger. The planners and analysts of educational development have been giving us signals for a long time. The quality of education is often poor, the efficiency is low, the questionable relevance and the waste is considerable, while the intentions and objectives are frequently blurred. In general, corruption is the abuse of roles of public resources for private benefits (Chapman, 2002). Seen strictly from the point of view of the educational sector, it can be defined as the abusive use of a public function in order to satisfy private interests which has a significant impact on the availability and quality of educational assets and services and a consequence on quality and equity in education.”

Corruption in higher education has some uncommon aspects. In many other areas where it exists, it is in the interest of both parties to prevent the advertisement of the dishonest action. If, for example, the dishonest nature of the awarding of a contract was made public, unsuccessful bidders could question the result. As common as corruption may be, there is often little that can be done in the absence of evidence.

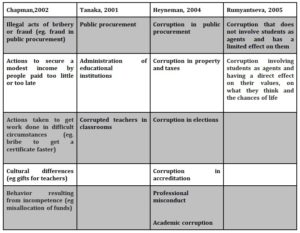

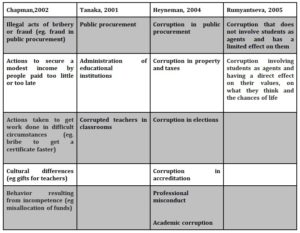

Table 1: Typologies of forms of corruption within the education system

Sources: Chapman, 2002; Tanaka, 2001; Heyneman, 2004; Rumyantseva, 2005, Hallak, J. and Poisson, M., 2007

Literature Review

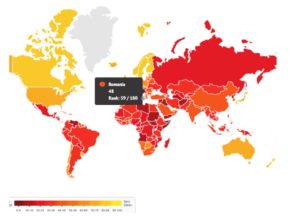

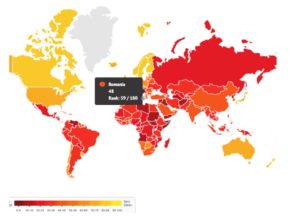

Normally, the magnitude of corruption is calculated by making it depend on how it is perceived. Therefore, the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), published by Transparency International since 1995, measures the degree of perception of corruption to establish whether there is corruption among officials and politicians, capturing the informed views of businessmen, academics and risk analysts all around the world (both residents and non-residents). It is a composite index, based on 16 different surveys of 10 public institutions. Countries that score close to 100 are considered “highly transparent” and those that score close to zero “highly corrupt”. According to Transparency International, Romania ranks 59 out of 180 in terms of corruption perception, with 48 points out of 100. Even more serious is the lack of change compared to the previous year, therefore, no progress has been made in the fight against this phenomenon.

Fig. 1: Corruption perception world map

Source: Corruption Perceptions Index 2017 by Transparency International licensed under CC-BY-ND 4.0

The Romanian Academic Society (SAR) is the oldest active think tank in Romania. Founded in 1996 as an academic association of well-known names, it has been, over the years, a public policy research institute, a leader in promoting good governance, a consultant to the Romanian government, but also to other governments, a long-term partner in transition and state reform of The United Nations, the World Bank, the European Union, before and after integration.

The Clean Universities Coalition ( www.romaniacurata.ro ), developed by SAR, is an integrity monitoring approach of good governance in universities, now at its third edition, being a developed concept and implemented for the first time by the Academic Society of Romania (SAR) and became a source of inspiration for experts and organizations around the world.

The Clean Universities Coalition (CUC) project aims to analyze problems related to the integrity of the university environment, given the numerous press reports about corruption acts that occur within the structures of the Ministry of Education which are not under control. The project targets augmentation of the degree of transparency of universities, given that the more transparent an institution is, the more credibility increases and becomes resistant to corruption attempts.

Research Methodology

Any well-defined concept in social sciences is measurable. Corruption in education is defined by UNESCO as an abusive authority for personal profit that leads to the violation of equity, integrity or access to education.

Corruption control in public education is defined in the context of this report as the ability to prevent and control deviations from universal access to education and academic integrity through insufficient use, inadequate or unethical nature of the teaching or administrative authority conferred by law, regulations and good academic practice.

The renewed methodology has been achieved through focus groups including teachers, students, educational policy experts and journalists. They analyzed the main problems of the university system in Romania, but also the impact of the new Law on National Education no.1 / 2011 on good policies Governance and Performance in Higher Education. Thus, the CUC methodology (third edition) maintains the classification of integrity issues established by experts in the field, it also uses the first two editions for the evaluation exercise. Besides the issues that refer to academic integrity, at the last evaluation, an important part of the final score was constituted by the performance component, following the qualification and output expected to university professors in research.

The evaluation of the universities took place in three stages:

- Stage 1: In the first phase there were collected -through the Free Access Law 544/2001

to the information of public interest- a series of documents related to the activity of

universities, their webpages and their releases, further analyzed by The National Anticorruption Directorate, the Court of Accounts and the National Agency for Statistics Integrity;

- Stage 2: In the second stage, mixed teams of senior assessors (teachers academics or experts) and students – visited each university and organized meetings with the main actors within them: representatives of the management, trade unions, teachers, student organizations and students;

- Stage 3: In the third step, the number of existing quotes on Google Academic were calculated using the “Publish or Perish” software. Each branch was created separately per science and per university involving the number of the PhD / capita supervisors’ quotes.

Academic integrity has been assessed from 2012 to 2016 in forty-two public universities out of a total of fifty-six, excluding art universities because the same evaluation criteria cannot be applied to them.

Data and Analysis

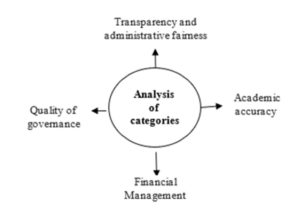

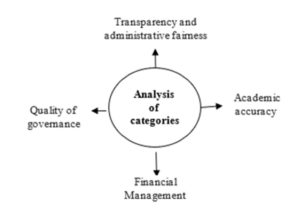

The comparison criteria have been established on the basis of a graph that represented the existing problems of integrity from the university system. Depending on the classification criteria, a number of problems divided into categories have been identified, to each one being awarded a score, depending on the relative importance it holds.

Fig. 2: Partition of categories

The evaluation was based on a questionnaire, with parties of joint teams shaped by experts and students. The teams visited 42 state universities where they interacted with the head of universities, students and trade unions.

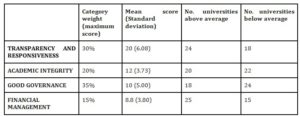

Transparency and administrative fairness (30 points)

The instrument underlying this analysis was Law 544/2001 on free access to information of public interest. In the first phase, the name of the contact person was requested to solve the demand for information. After 30 days – the legal term – a series of 16 documents were inquired, including the activity report of the previous year, the accounting budget, the wealth statements of the university staff, internal regulation, collective labor contract, etc.

If universities responded affirmatively to the first application, they were awarded with 5 points, one for each document. They were also granted a maximum of 5 points for an up-to-date website and a maximum of 4 points if information on teachers, CVs, published works available online, electronic catalogs were available on the website.

Academic accuracy (20 points)

Four categories of analysis were evaluated with the following scores: maximum 5 points if there were rules and procedures in the university against copying, if regular checkups are made and the phenomenon is controlled; maximum 5 points if there are ISI papers in doctoral school; maximum 10 points for two cumulative categories, namely; the observance of the academic process through the participation of teachers and students at classes and the existence of contesting commissions for admission and license exams.

Quality of governance (35 points)

Within this indicator, the score was accorded as follows:

- 10 points for an open system; this refers to the way in which the posts are filled, the possibility of them being “reserved” to certain persons, a relevant indicator is the presence of several candidates for competitions;

-

10 points for the presence of university teacher’s relatives within a faculty and the existence of regulations against this phenomenon; the score was given according to the gravity of the situations;

-

5 points for universities where students have a real role in decision-making;

-

5 points for the level of academic and scientific achievement of the academic staff with career upgrading;

-

5 points for the way the merits are awarded in the respective university- the degree of correlation with the international scientific work of the teachers.

Financial Management (15 points)

Given that the evaluation teams were not arranged of financial analysts, the study of the financial documents was done in a simplistic manner, following the balance of the grant accounts for which they were granted up to 5 points. The following 5 points were granted for the extent to which purchases were made in accordance with rules and practical goods. A comparative analysis of wealth and interest statements was finally carried out and a maximum of 5 points were granted if they reflected a justifiable situation of the financial resources of teachers.

Methodological Limits

This research was built in accordance with the CUC’s vision of what academic integrity should represent. Although the size of the questionnaire seeks to address as many problems as possible, there are a number of implicit limits to data collection using the survey. Last but not least, the subjectivity of the assessment team may intervene, although precautions have been taken to limit this by organizing training.

Research Findings

In terms of administrative transparency and accountability, none of the universities have succeeded in achieving the maximum score. Only 38% of them have been transparently administratively compliant with requests under Law 544/2001, demonstrating that universities either disregard this law, or do not know how they apply or do not know about it. Another law not fully taken into account is Law 144/2007, 16 out of 42 universities have public and up-to-date declarations of assets and interests, while 13 of them refuse to make them public. Failure to comply with this regulation should impose sanctions from the National Integrity Agency (ANI). Another element that highlights the opacity of universities is the lack of essential information, such as job contests, teacher performance, content of university courses, etc. on the university website.

Regarding academic correctness, there is only one university that meets the conditions to obtain the maximum score, namely “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iasi. One of the main problems encountered in the Romanian educational system is related to the plagiarism of the works, both for students and teachers. More worrying is the fact that although there are rules to combat the phenomenon, they are only on paper, very vague and interpretable conceived. In the matter of the scientific performance of ISI publications in the university, the results are not satisfying: in 26% of universities, the average number of ISI articles published by a doctoral supervisor within the doctoral school is higher than 2, in 38 % is between one and two items, and in 36% of the cases the number of articles is below one. According to the IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking, Romania is ranked 50th in the world with regard to ISI countrywide publications, being among the last countries in the EU and from this point of view. Regarding attendance at courses and seminars, in 76% of the cases, this can be considered reasonable, while in 79% of them, students are free to challenge admission exam notes, license, etc.

A more delicate chapter is the quality of governance; given that it averaged 10 points out of 35, it truly reflects the severity of the situation. The best score obtained by a university is 25 points, well below the maximum. A first problem is given by the correctness of the employment process of the teaching staff. Although official legal compliance is observed, only one candidate is present in most competitions, so the posts seem to be assigned to some people before the examination takes place. It is very serious that 95% of universities have identified a large number of university families. A relevant example may be the existence of eight pairs of related persons, spouse or father-son, within a single faculty, in a total of 45 teachers. Nepotism is a difficult phenomenon to control, especially since teachers often find it inappropriate to block a relative’s access to a university career for reasons strictly related to the relationship of kinship, not taking into account the level of performance. In terms of student involvement in the decision-making process, only 21% of the cases meet the conditions of student participation in decision-making. In the case of 74% of universities, a correlation between the awarded merit degrees and the professional value of the teaching staff could not be identified, so there was no specific methodology for granting them.

As far as financial management is concerned, the possibility of misappropriation of funds, in other words, the storage of different amounts of money in certain budget chapters was checked to be later moved into budget chapters more easily to manipulate. Thus, 38% of universities have been proved to be opaque, not providing the assessors with the mandatory documents. In many of these cases, irregularities had been reported even by the Court of Accounts. Regarding public acquisition, it has been found that there are many cases where they have already been “established”, because companies that consistently win auctions, procure acquisitions through calls for tenders or even through some single source negotiations, not through open auctions. In 60% of the cases, the comparative analysis of wealth and interest statements was not possible either because this information is not published or because it is not up to date.

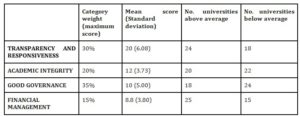

Table 2: Final assessment of governance practices brief results

Penalties were applied to 52% of universities for one or more of the following categories:

- 16% of universities were in trial with employees and / or students on fairness issues and lost;

- In 14% of them, there were cases which investigated the prosecution for corruption, sexual harassment, discrimination, etc., more than a year, over the last four years;

- 17% received negative reports from the Court of Accounts, the Financial Guard, OLAF, the Control Corps, etc. in the last four years;

- In 10% of the cases, there has been evidence of grave falsification of diplomas over the past 10 years.

Discussions

After the final results, Romanian universities ranked as following:

✰✰✰✰✰ Universities

There are no 5-star universities in Romania.

✰✰✰✰ Universities

- Universitatea de Medicină și Farmacie, Târgu Mureș

- Universitatea de Medicină și Farmacie “Iuliu Hațieganu”, Cluj Napoca

- Universitatea “Alexandru Ioan Cuza”, Iași

Four-star universities are the best in the Romanian context, not like five stars though, so they are below what they could have done even with the most favorable benchmark. All universities have integrity problems, but also the ability to progress. The diplomas of these universities should receive added confidence in the area of integrity and competence in the labor market.

✰✰✰ Universities

- Academia de Studii Economice, București

- Universitatea Maritimă, Constanța

- Universitatea Politehnică,București

- Universitatea de Petrol și Gaze, Ploiești

- Universitatea “Ștefan cel Mare”, Suceava

- Academia Națională de Educație Fizică și Sport, București

- Universitatea Tehnică “Gheorghe Asachi”, Iași

- Universitatea de Medicină și Farmacie, Craiova

- Universitatea din București

- Universitatea “1 Decembrie 1918”, Alba Iulia

- Universitatea “Dunarea de Jos”, Galați

- Universitatea de Arhitectură și Urbanism” Ion Mincu”, București

- Universitatea de Medicină și Farmacie “Victor Babeș”, Timișoara

- Universitatea de Științe Agricole și Medicină Veterinară a Banatului, Timișoara

- Universitatea de Nord, Baia Mare

- Universitatea Tehnică de Construcții, București

- Universitatea “Babes-Bolyai”, Cluj-Napoca

- Universitatea “Petru Maior”, Târgu Mureș

Three-star universities have potential, although NAD (National Anti-Corruption Division) has surprised us recently with a visit to one of them under the accusation of selling diplomas. They need to eliminate their weaknesses and emulate the strategies of better placed universities.

✰✰ Universities

- Universitatea “Valahia”, Târgoviște

- Universitatea de Medicină și Farmacie “Grigore T. Popa”, Iași

- Universitatea Politehnică,Timișoara

- Universitatea din Petroșani

- Universitatea de Vest, Timișoara

- Universitatea “Transilvania”, Brașov

- Universitatea de Științe Agricole și Medicină Veterinară, Cluj Napoca

- Universitatea de Științe Agricole și Medicină Veterinară “Ion Ionescu de la Brad”, Iași

- Universitatea Tehnică, Cluj Napoca

- Universitatea din Pitești

Two-star universities should build on their own – they have enough capacity – programs to increase integrity and quality. Students, trade unions, and communities in which they operate need to ask for and support this process.

✰ Universities

- Universitatea din Bacău

- Universitatea “Lucian Blaga”, Sibiu

- Universitatea “Ovidius”, Constanța

- Universitatea din Oradea

- Universitatea din Craiova

Universities with a single star should not have doctoral schools. They should be given a grace period to resolve their problems under the supervision of another institution.

No-star Universities

- Universitatea “Constantin Brâncuși”, Târgu Jiu

- Universitatea “Aurel Vlaicu”, Arad

- Școala Națională de Studii Politice și Administrative, București

- Universitatea “Eftimie Murgu”, Reșița

- Universitatea de Medicină și Farmacie “Carol Davila”, București

- Universitatea de Științe Agronomice și Medicină Veterinară, București

Universities without any star are problematic for academic and administrative integrity. The Ministry of National Education and Research (MENCS) and the Romanian Agency for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ARACIS) should reflect on their radical abolition or reform.

Conclusions and Further Research

There are many measures that universities could take to create a system that works on a number of healthy principles. First, the laws should be respected and enforced, and corruption attempts should be severely punished. Thus, loyal and constructive competition could be created, motivating both students and teachers. Moreover, it would create a system in which there would be confidence in the quality of others’ work, leading to transparency and integrity.

Another sensitive point is the quality of teaching staff, whose academic performance should be encouraged. Major attention should be paid to research, making it impossible for the system to rise to the qualitative level of Western universities, as the majority of coordinating teachers of the doctoral schools have no scientific papers published in the international academic journals. Another phenomenon that needs to be limited is nepotism; one cannot speak of ascension through performance in the conditions in which one third of the staff is related. Another fact that should be severely sanctioned is the absenteeism of the teaching staff.

A problem that needs to be worked on is related to the transparency of public universities with regard to public information. It is imperative that a state university has a user-accessible interface, containing all information of public interest, as well as those that allow a future student to choose his / her faculty in knowledge. It would be advisable to have in each university a person in charge of solving the requests for public information. Last but not least, to curb corruption and improve the quality of services through which students do benefit, their contribution is also highly needed.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Chapman, D. (2002) Corruption and the education sector. Sectoral perspectives on corruption. Prepared by MSI. Sponsored by USAID, DCHA/DG (unpublished);Corruption Perception Index 2017, Transparency International. [Online] last accessed on 24.01.2018. Available ; https://www.transparency.org/country/ROU;

- Hallak, J.; Poisson, M. (2002). Ethics and corruption in education. Results from the Expert Workshop held at the IIEP. Paris, 28-29 November 2001. IIEP. Observation program. Policy Forum No. 15. Paris: IIEP-UNESCO;

- Hallak, J.; Poisson, M. (2007), Corrupt schools, corrupt universities: What can be done?, International Institute for Educational Planning,[Online] last accessed on 20.01.2018. Available: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001502/150259e.pdf ;

- IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2017. [Online] last accessed on 20.02.2018. Available :https://www.imd.org/globalassets/wcc/docs/release-2017/world_digital_competitiveness_yearbook_2017.pdf ;

- MENCS, Proposals for minimum and mandatory standards for conferring the status of PhD coordinator and attestation of qualification, respectively obtaining university degrees, [Online] last accessed on 20.02.2018. Available: https://www.edu.ro/dezbaterepublic%C4%83-propunerile-de-standarde-minimale-necesare-%C8%99i-obligatorii-pentru-ob%C8%9Binerea ;

- Mohamedbhai, G. (2016). The scourge of fraud and corruption in higher education. International Higher Education, 84, 12-14;

- Mungiu-Pippidi, A., & Dusu, A. E. (2011). Civil society and control of corruption: Assessing governance of Romanian public universities. International Journal of Educational Development, 31(5), 532-546;

- Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2015). The quest for good governance: how societies develop control of corruption. Cambridge, last accessed on 25.01.2018. Available: http://legislatie.resurse-pentru-democratie.org/legea/544-2001.php ;

- Osipian, A.L. (2009). Investigating corruption in American higher education: the methodology: Evolving Trends in Higher Education, Corruption and American Higher Education, The Fed Uni Journal of Higher Education, May 49-81;

- Rumyantseva, N.L. (2005). Taxonomy of corruption in higher education. In: Peabody Journal of Education, 80(1), 81-92. Mahwah, N. J. (USA): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.;SAR Study on the evolution of corruption in Romania since 2004, [Online] last accessed on 05.02.2018. Available : http://sar.org.ro/files/547_Coruptie.pdf ;

- Tanaka, S. (2001). Corruption in education sector development: a suggestion for anticipatory strategy. The International Journal of Educational Management, 15(4), 158-166. MCB University Press.;

- The list of doctoral supervisors used for data collection was published in January 2016 by the Ministry of National Education and Research. [Online] last accessed on 10.02.2018. Available : https://www.scribd.com/doc/295874468/Lista-Scolilor-DoctoraleIanuarie-2016 ;

- The second edition of the Clean Universities Coalition (2008-2009). [Online] last accessed on 24.01.2018. Available : http://www.romaniacurata.ro/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Raport-CUC-II.pdf ;

- The third edition of the Clean Universities Coalition (2015-2016). [Online] last accessed on 25.01.2018. Available: http://www.romaniacurata.ro/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/RaportCUC-depuspesite.pdf .