Introduction

“In addition to the commitment of banks to large companies in providing support and financing, we encourage them to fulfill their predominant mission in promoting development. To this end, they must simplify and facilitate the procedures for accessing credit, be more open to self-employed entrepreneurs, and finance small and medium-sized enterprises. In this regard, we invite the government and the Bank of Morocco (Bank Al-Maghrib), in coordination with the Moroccan banks’ professional group, to work on the development of a special program that supports young graduates and finance self-employment projects”.

These are the words of His Majesty the King Mohammed VI at the presentation ceremony of the “Integrated Program of Support and Financing of Enterprises” and the signing of related agreements held on 27 January 2020. The President of the Professional Grouping of Banks in Morocco also added that “Each bank is committed to providing young project holders and small and medium-sized enterprises with all the support they require, in terms of proximity, advice, coaching and training, in all economic sectors and in all regions of the Kingdom”.Le Matin “Une Vision Royale pour la promotion de l’entrepreneuriat” (Accessed on 03/24/2021)

Likewise in other countries and in a constantly changing socioeconomic context, unemployment is one of the major problems in Morocco nowadays. In this regard, entrepreneurship is seen as a positive value, a generator of wealth and a factor of fulfillment for young people who are increasingly interested in entrepreneurship. Consequently, for the past few years, entrepreneurship training has aroused a strong interest among many entities: support structures, large companies, universities and high schools.

In this sense, if scientific research has now largely answered the question “Can entrepreneurship be taught?”, many questions remain open, such as: What training should be provided to become an entrepreneur in Morocco?

Through an analysis of the “Entrepreneurship training programs at the Moroccan university: contributions, limits and perspectives”, El Ganich et al. (2019) pointed out many shortcomings such as improving awareness and training, avoiding redundancy in services rendered and involving more entrepreneurs and business professionals in aspects such as training, conferences, personal testimony and the jury of project selection, to ensure the complementarity of services provided to students by teachers and professionals. Consequently, due to the lack of research that connects Moroccan entrepreneurs to educational training, and in order to address this issue, the authors of this paper will first discuss some theoretical guidelines on entrepreneurship education; then, through semi-structured interviews, they will explore the current state of entrepreneurship in Morocco and the training needed to improve the entrepreneurial educational ecosystem. These interviews were held with Moroccan entrepreneurs who have diverse backgrounds and who operate in a variety of fields, such as education, web development, human resources, public affairs, handicrafts, personal development, IT security, dentistry, event management, fintech, real estate, design, health technology, and gardening. In this regard, what determines the sample size in this study is the saturation. Through the conceptually Clustered Matrix (Huberman and Miles, 1991), the results of the qualitative study will be discussed in terms of 5 main axes which are as follows:

- Age and decisions to start a business;

- Gender and entrepreneurial intention;

- Parallel training programs and entrepreneurship;

- Skills, knowledge and entrepreneurship;

- Educational ecosystem and entrepreneurship.

About The Entrepreneurial Educational Ecosystem

Entrepreneurship – Definition and evolution

The word “entrepreneur” appeared in economic literature in the 18th century, and most theories prior to Schumpeter state that the entrepreneur is an agent who reacts to changes in the economic environment. In Schumpeter’s analysis, the entrepreneur is, on the opposite, a dynamic, proactive and endogenous agent (Schmitt et al., 2008).

Since that time, the field of entrepreneurship research has grown significantly (Landström et al., 2012), first by considering entrepreneurship as an economic function and then by estimating the entrepreneur as an individual with particular personality traits. As such, it is clear that the notion of entrepreneurship is polysemous and equivocal. Shane and Venkataraman (2000) propose a definition that connects the individual to opportunity by suggesting that entrepreneurship is a field where various opportunities for future goods and services are explored. Furthermore, the entrepreneurial phenomenon can be explained as a process. Bessant and Tidd (2015) stated that the entrepreneurial process can be viewed as a four-step process including: recognizing the opportunity, finding the resources, developing the firm and creating the value. In the meantime, academic advancements in the field of entrepreneurship had considerable implications on the development of entrepreneurial education. After the emphasis on the entrepreneur as an individual with special characteristics, entrepreneurship has been shown to be developable, not an innate personality trait. This therefore requires considering the importance of entrepreneurship education.

Entrepreneurship Education – Concept and Evolution

The first entrepreneurship class was taught at Harvard University in 1947 by Myle Maces (Katz, 2003). Since the 1950s, Solomon & Fernald (1991) emphasized that entrepreneurship education has grown impressively. (Fones & English, 2004) added that in the following years, entrepreneurship was considered an important area in business education.

Despite this enthusiasm, the fact remains that the educational goals and objectives are still difficult to define. This is due to the fact that one of the most obscure areas concerns not only the polysemous definition of the concept of entrepreneurship itself, but also the concept of teaching in this field. As such, researchers are contributing to an evolving definition of the latter’s concepts. According to Binks et al. (2006), entrepreneurship education refers to “the educational process involved in fostering entrepreneurial activities, behaviors, and mindsets…”

For Tounes (2003), a training (whether it is awareness-raising, coaching or mentoring programs) is qualified as entrepreneurial if it aims to prepare and develop entrepreneurial perceptions, attitudes and skills. Entrepreneurship educational initiatives promote multidisciplinary interaction (engineering, business, design, etc.).

As claimed by Hytti and O’Gorman (2004), it is important to mention that programme contents and teaching approaches differ from institutions in different countries, and even among those within the same country.

Entrepreneurship education can be approached through its main objectives. (Jamieson, I., 1984 and Henry, C. et al., 2005) identify the three following goals:

- Education about entrepreneurship: It concerns the general theoretical aspects of starting and sustaining a business. According to Hytti (2002), it also involves raising awareness for the benefit of different entities such as political decision-makers, financiers, organizations, civil society, etc.

- Education for entrepreneurship: It aims to support new or potential entrepreneurs with practical skills to stimulate the entrepreneurial process.

- Education in entrepreneurship: Henry, C. et al., (2005) define it as an education that seeks to make people more entrepreneurial in their business or work. As stated by Mário, R. et al. (2011), education in entrepreneurship also aims to train people who are already entrepreneurs. It includes training in business management, e.g. management principles, business growth, product development and other marketing courses. Such programs provide entrepreneurs with the skills, knowledge and attitudes to be innovative in solving their personal and business problems. In this regard, this research proposes to unravel an “Entrepreneurial Educational Ecosystem” (Toutain et al., 2014).

Entrepreneurial Educational Ecosystem: Concept and Evolution

The notion of the Entrepreneurial Educational Ecosystem was generated from the application of the ecosystem concept to the context of entrepreneurship education. In fact, over the past two decades, the discipline of entrepreneurship has shifted from the study of entrepreneurs and the economics of entrepreneurship to a much broader topic, incorporating the promotion of entrepreneurial behavioral patterns of firms, individuals, and institutions, university-industry-government partnership, start-ups and scale-ups, as well as entrepreneurial aspirations and orientation (Lee, 1996; Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000; Markman et al., 2005; Bonaccorsi et al. 2013).

Hence, the entrepreneurial educational ecosystem has emerged as a complex system that involves multiple collaborative ties among multiple key stakeholders, such as the university, the corporation, the government, the student, and the researcher, and involves a connection to the adjacent elements that promote or hinder the transfer and commercialization of knowledge by both the industry and the university (Wright, 2006).

The ‘triple-helix’ model proposed by Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (2000) puts the university at the centre of the university-industry-government relationship and emphasizes the eminent role universities can have for innovation and economic development in a Knowledge Society.

Autio et al. (2014) consider the entrepreneurial educational ecosystem to be a dynamic, institutionally embedded interaction between the university and entrepreneurs, characterized by entrepreneurial attitudes, capabilities, and aspirations, which determine the allocation of resources through the creation of new ventures (spin-offs) or technologies (university-industry partnerships).

Methodology of the qualitative exploratory study

This section will focus on the methodology of the chosen qualitative study.

The Choice of The Convergent Interview Method

The objective of this study is to examine the training that has helped Moroccan entrepreneurs succeed, and to explore what is lacking in the Moroccan entrepreneurial ecosystem. In order to conduct this study, the authors opted for the convergent semi-directive interview method.

The semi-directive or semi-structured interview is the method most commonly used in management. It is conducted with the help of an interview guide (or grid or outline), which is a sort of a list of themes/topics to be discussed with all interviewees. However, the order of discussion is not imposed. The interviewer relies on the respondent’s own sequence of ideas to bring up one topic before or after another. This flexibility of the semi-structured interview allows the respondent to better understand his or her own logic, while at the same time, the formalization of the guide helps to promote comparative and cumulative analysis strategies between respondents, and is better suited to certain field limitations (low availability of respondents) and to the skills of the interviewers (often restricted) (Le Louarn, P., 1997)

On the other hand, the convergent interview describes how several objects (e.g. several decisions) are articulated over time to converge towards a single object (i.e. a single decision). This convergence model describes a process by which the variety is reduced as time flows by. This process is no longer guided by a clear diagnosis or a clear target, but rather by the idea of successive approximations that appear gradually. In other words, the convergent interviewing process consists of a series of long, initially unstructured interviews in which data are collected during each analysis, and then analyzed and used for the content and process of subsequent interviews (Dick, 1990). In this case, in the course of this research and in the interviews conducted, new issues were identified, thereby raising new and relevant research questions and research perspectives.

Determination Of Sample Size

Research has suggested different sample sizes for the convergent interviewing method. Dick (1990) suggested that the sample size should be one percent of a target population of up to 200, and the minimum sample size should not exceed 12 people. Others have argued that the sample size is determined when saturation is reached, when agreement among respondents on the issues is reached and disagreement is explained (Naire & Riege, 1995). The suggested saturation can occur after as few as six interviews; however, Woodward (1997) found convergence after five interviews.

This saturation approach was adopted in this research to determine the number of interviewees. That is to say, maximum information gathering was the primary objective of the convergent interview for this research, which was achieved when saturation occurred. Therefore, the authors conducted a total of 15 interviews before the saturation described above, had been achieved.

The Sampling Method Chosen

In addition to the sample size, the sampling method must also be determined. In qualitative research, the sample should be as heterogeneous as possible and relevant to the issues being studied (Dick, 1990). Thus, a random sampling method is more appropriate (Patton, 1990). Regarding heterogeneity, this research initially selected a small and diverse sample of competent individuals who did not know each other; after each interview, interviewees were asked to recommend others who should be examined. In other words, the authors started with a few cases and used these cases to identify others in the interconnection network to interview, allowing the sample to grow in size (Aaker, Kumar and Day, 2001; Neuman, 2000). Such a snowball sampling technique is appropriate when the research involves a small, specialized population of people who are familiar with the topics (Aaker, Kumar and Day, 2001; Neuman, 2000; Patton, 1990).

15 interviews were conducted to reach saturation, as indicated above. The interviews were conducted with Moroccan entrepreneurs who work in different sectors and whose backgrounds are different.

Analysis And Interpretation of The Qualitative Study Results

In this section, the authors analyze the data collected from the convergent semi-structured interviews.

Sample Constitution

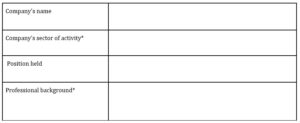

First and foremost, it is important to mention that this exploratory survey took place between January and April 2021. The length of the process is explained by the fact that the authors chose to conduct these interviews with entrepreneurs working in various sectors, of different age groups and also within the intense rhythm of life that an entrepreneur leads, especially during the current health and economic crisis. In addition, the authors also made sure to respect the principle of parity among interviewees (7 women and 8 men).

Table 1: Summary table of the areas in which the interviewees operate

Results’ Method Analysis

The conceptual grouping matrix was used from the work of Huberman and Miles (1991) in order to analyze and interpret the content of the interviews. “In a conceptual grouping matrix, the columns are arranged in such a way to bring together items that “go together”. This can be done in two ways: conceptually, when the analyst has some initial ideas about which items or questions are derived from the same theory or related to the same overall theme, or empirically, when it is discovered during data collection or pre-analysis that informants are making connections between different questions or giving similar answers. In either case, the basic principle is conceptual consistency”. The purpose of constructing matrices is, in fact, to organize the data in a way that shows “what is happening” or explains why things are occurring the way they do.

Matrix Construction

In this study, fifteen questions were asked which were grouped into five themes: age, gender, alternative education, skills and knowledge, and the educational ecosystem. These themes are reflected in the row of the matrix. Moreover, the column of respondents was split up according to the sector of activity in which the group operates. For confidentiality reasons, the names of the respondents will not be included in the final report, but rather the data will be analyzed by the sector of activity of their company.

Analysis of matrix data – by axis and by interviewee

A line-by-line reading allows getting a brief idea of each entrepreneur and verifying the relationship between the answers to the different questions. A column-by-column reading allows, in turns, comparisons to be made between respondents and between the different axes.

Study validity and reliability

The validity of a research study is “the capacity of the instruments to effectively and truly assess the object of the research for which they were created” (Wacheux, 1996). As recommended by Yin (1989), validity can be divided into different types as follows: construct validity, internal and external validity of the results.

Construct validity (conceptual or theoretical) refers to the development of appropriate operational measures for the concepts under study (Emory & Cooper, 1991). In this study, convergent interviews enabled construct validity through three tactics. First, the triangulation of interview questions was established at the research design stage through two or more carefully crafted questions that examined the topic from different perspectives. Secondly, the convergent interviewing method included an embedded negative case analysis where, in each interview and before the next, the technique explicitly requires the interviewer to attempt to refute emergent explanations interpreted in the data (Dick, 1990). Finally, the flexibility of the mode allowed the interviewer to reevaluate and redefine both the content and process of the interview program, which allowed the authors to validate the content.

Internal validity is “a process of checking, questioning and theorizing; it is not a strategy that establishes a standardized relationship between the results of analyses and the real world” (Miles & Huberman, 2003). In other words, internal validity is about ensuring the relevance and internal consistency of the results generated by the study (Drucker-Godard et al., 1999). The internal validity of the convergent interviews in this research was achieved through sample selection based on the “richness of information” (Patton, 1990).

External validity refers to the generalization of the results (Yin, 2003). In this research, the external validity was achieved through theoretical replication in the selection of the interviewees, by selecting entrepreneurs operating in different sectors, to ensure that a number of various perspectives were provided.

On the other hand, the reliability of the research stipulates that the researcher involved in a scientific team must be able to transmit, as faithfully as possible, the way in which he/she conducts research (notion of diachronic reliability according to Kirk and Miller (1986), which examines the stability of an observation over time). The same researcher must be able to accurately replicate a research project that he or she has previously conducted, for example when conducting a multi-site research project over several months (notion of synchronic reliability according to Kirk and Miller (1986), which examines the similarity of observations over the same period of time).

Thus, this search ensured its reliability through three tactics. First, reliability was achieved through the structured semi-structured convergent interview process that was previously detailed in Section 2.1. Second, reliability was achieved through the organization of a structured process for collecting, writing, and interpreting the data. The authors replicated the content analysis of the interviews several weeks after they had first conducted them in order to compare the “old” results with the “new” ones – in other words, the authors used themselves as a check (Romelaer, 2000).

Finally, using a steering committee to assist in the design and administration of the interview program is another way to achieve reliability (Guba and Lincoln, 1994). To achieve this purpose, the authors consulted with the thesis advisor about the results, acting as a steering committee to assist in the design and administration of the interview.

Findings Of the Qualitative Study

This section focuses on presenting the analysis’ findings based on the conceptual grouping matrix developed out of the 15 interviews. The purpose of these interviews is to provide qualitative answers to five main categories of questions that will help the authors better understand the research topic: age, gender, alternative education, skills, knowledge and entrepreneurship, and finally the educational and entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Age And Decision to Be an entrepreneur

In this research and as an introduction, the authors asked the interviewees the following two questions: “How and when did you get the idea to start a business?” and “According to you, what is the ideal age for entrepreneurship? And why?”

In response to these questions, two trends emerged in the interviewees’ discourse: the first category of respondents specified that entrepreneurship had no age; while the second category affiliated the action of entrepreneurship with the need to have acquired a certain professional experience.

Thus, the respondents of the first category prevailed that:

“The older you get, the more responsibility you have”, or “entrepreneurship has no age. It’s a very personal path; you can have the maturity to be an entrepreneur at 10 years old as well as at 50 years old”. They also added that “There is no precise age; it’s when the intuition is there and ideally before having received your first salary”.

The second category of respondents advocates starting at a more specific age. In addition, one of the respondents specifies that for him, the ideal age for entrepreneurship is 16 years old, supporting his argument by saying the following:

“In the United States, young people can start working early and the majority is independent at the age of 18”. In this same sense, another response states that the ideal age would be “4 years after graduation, because it gives you time to gain experience in team management and tips to deal with daily tricky situations”.

Three respondents argued that the ideal age ranges between their 30s and 40s, and that it is “by the time you gain networking knowledge”, or in other words, “Once, some experience in the sector is gained” justifying this as follows: “because the merit of experience and networking should not be omitted”.

Finding 1: Age is not a variable to consider. Meanwhile, work experience does play an important role.

Gender And Entrepreneurial Intention

Referring to the matrix, three main points of view can be identified. The first argues that women are less entrepreneurial than men; the second argues that women are more entrepreneurial than men; and the third argues that women are as entrepreneurial as men.

Thus, it would be interesting to correlate the answers to this question with the gender of the respondents and the sector in which they operate.

In fact, the first group – those who argue that women are less entrepreneurial than men – justifies its point of view by saying that:

“Women have more challenges to overcome and prejudices to debunk (social pressure, clients…)”, and that despite of “the difficulties that men face, we are confronted with societal realities: perception of the status of women (mother, less competent, doesn’t need to work, harassment, not serious, emotional, and so on) as well as societal pressure that doesn’t allow us to take risks”.

Two respondents supported their argument with personal feedback:

“For having experienced harassment in my daily life, I no longer visit suppliers alone“, the second added that “The woman must also prove herself more than a man to aspire to a position of responsibility”.

One respondent that works in the recruitment of high-potential profiles pointed out that “Women dare less and do not value themselves enough”.

An interviewee, a Business Angel, founder and CEO of a company specialized in web development explained that:

“Women certainly have less facility than men to start their own business, but they are naturally equipped with certain qualities that allow them to attract luck, such as perseverance and patience”.

The second group affirming that women are more entrepreneurial than men is mostly composed of men. They stated that by nature, women are more inclined to be entrepreneurs by saying that “Women are very diplomatic by nature. From what I see in my field of activity – dental surgery – women have potential and therefore more chance to succeed than men”.

In the very same sense, the following answer has been obtained: “Women consume a lot more than men; they tend to better know their clients. Consequently, they have the most chances to succeed”. Also, many interviewees noted the increasing national and international support to women entrepreneurs: “In the name of equality, they now have more access to the market (associative and governmental tenders)” and that “there are more and more programs dedicated to women”.

Others highlight the position of women in the Moroccan society and the inequalities that result from it, stating that “In a company, a woman’s salary is lower than that of a man, which makes choosing the path of entrepreneurship easier” or that “In the Moroccan society, when a woman gets married, it is up to the man to ensure the needs, so it is easier for her to be an entrepreneur”.

The third group advocates equal opportunities and the easiness to become an entrepreneur for both men and women because “It is the originality of the idea that increases the chance of success (Business Model Canvas)” and that “Entrepreneurship requires passion and work from both men and women”. It should be noted that the respondents in this category are women who work in education, wellness and personal development.

Finding 2: The gender variable and entrepreneurship are strongly impacted by the business sector in which the entrepreneur operates.

Alternative Training and Entrepreneurship

All the entrepreneurs interviewed had previously participated in entrepreneurship training or volunteered at least once in their lives. These trainings can be grouped into: school and university programs, programs in collaboration with international entities, programs in collaboration with Moroccan institutions, universities or independent organizations and professional experience. It is worth noting that the majority of respondents have received more than one entrepreneurial training.

Thus, school and university programs include subjects such as “business simulation and associative action project”. Moreover, one of the participants said that he was influenced by his Master’s degree in entrepreneurship, justifying it as follows: “The master I did allowed me to develop my entrepreneurial mindset, to get to know entrepreneurs’ paths, to consider risk taking, to change my perception on failure and to be more persevering”. Another respondent described the experience of participating in an entrepreneurship awareness workshop in high school as a “wake-up call”. Also, while in college, one interviewee stated that “there were entrepreneurship training sessions by entrepreneurs that advocated the entrepreneurial lifestyle by telling their stories. This was very inspiring to me. In fact, that’s what made me want to give it a try”.

Besides, the respondents highlighted programs in collaboration with international entities, stating that” Thanks to Enactus (ex-Sife), I was able to conduct training for cooperatives and represent my school internationally”, said an entrepreneur that operates in the field of education. A second participant founded her leather goods business within Enactus. Additionally, one respondent said that he was positively impacted by one of the Rabat TedX in which entrepreneurs shared their stories.

Furthermore, respondents emphasized the importance of programs held in collaboration with Moroccan institutions. In fact, one respondent gave the following example of impactful training: “Injaz Al Maghrib’s youth entrepreneurship program that I took part in at the age of 17 changed my perception of what I can expect as a future professional activity”. The Belgian-Moroccan training program to support female entrepreneurship Min ajliki was also mentioned.

Therefore, Non-Governmental Organizations and social enterprises are particularly important for the vast majority of respondents, as the following verbatims indicate:

“Associative work allowed me to develop useful skills for my clients (video editing, graphic design…)” or “I was the president of my school’s alumni association, that’s what helped me envision myself following the paths of entrepreneurs that were studying in my college”. Moreover, an interviewee detailed what her associative experience allowed her to achieve by saying that “Volunteering in humanitarian and cultural associations taught me the necessary skills of project management and to know these sectors more in depth”.

For instance, 80% of the respondents have been part of an association at some point, whether as a member of a junior enterprise or of local, national or international organizations.

The gap year or work-study period was mentioned by respondents who chose to study abroad as an important step for the genesis and maturation of the entrepreneurial idea.

Finally, the professional experience was also identified as one of the most important steps that made the interviewees want to become entrepreneurs. In this sense, a respondent specified that: “joining happy smala, an innovation and collaborative finance laboratory, allowed me to discover new concepts. I was able to be an entrepreneur in several ways: as an employee, by managing a project, by creating and managing a company, by participating in consulting missions, by representing the company…”. Also, one interviewee admits that he would not have been an entrepreneur without his mentor. In addition, one respondent found the opportunity and the desire to be an entrepreneur by working as an event project manager in a yacht club.

Finding 3: All entrepreneurs demonstrated a commitment that greatly affected their entrepreneurial intent. Programs resulting from partnerships between businesses and universities or between universities and international entities are identified as the most impactful.

Skills, Knowledge and Entrepreneurship

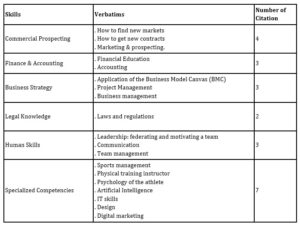

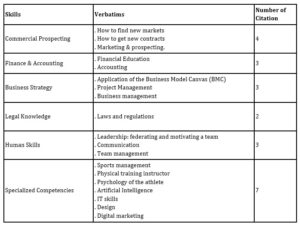

In order to explore what the entrepreneurs of this study would have liked to have acquired beforehand, they were asked the following question: “What skills/training would you have liked to have acquired/received beforehand?”

Two types of answers were received. The first one suggested the need for “More feedback from entrepreneurs rather than training sessions, and more concrete case studies on crisis situations or problems and how entrepreneurs have reacted to solve them as well as how entrepreneurs manage to find a balance between professional and personal life”. The second typology of responses that considers the need for specialized expertise could be grouped as follows:

Table 2: Table of skills and knowledge that interviewees wished

they had previously acquired

Finding 4: The skills and knowledge that entrepreneurs would have liked to have received beforehand are diverse and in most cases, different from the training they had and the majors they have chosen.

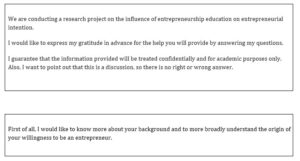

Educational Ecosystem and Entrepreneurship

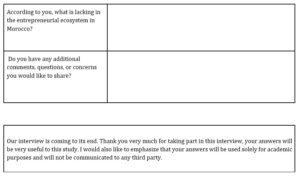

Since entrepreneurs are the backbone of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, they were asked the following question: “According to you, what is lacking in the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Morocco?”

A variety of answers was gathered and summarized into three major areas: skills and training, human values, and legal and economic incentives.

In the first part, that of skills and training, the following needs were noted: “How to finance your business idea and how to approach business angels” or the need for “coaching young project leaders; training technicians; training in finance; and training in strategy, crisis management and communication”. Also, there is the need to provide the country with more “networks of mentors; namely mentors with at least 30 years of experience in a specific field who are involved in accompanying and coaching entrepreneurs”.

As for the second part concerning human values, the interviewees underline the “lack of trust that prevails”. Another respondent referred to the greed that he experiences on a daily basis.

The third area is the lack of legal and economic incentives. This last part includes “the lack of warranties, unpaid bills, the slowness of the process of starting a company, as well as the difficulty of obtaining a public contract”. Moreover, in the same regard, interviewees mentioned “the lack of spaces where people can network, the need to create specialized incubators, the importance of facilitating the companies’ domiciliation, especially for youths, the need for reducing taxes, the signature of partnerships between the different stakeholders of the ecosystem and the increasing involvement of the State”.

In this sense, a respondent specified that “Civil society has undertaken several actions in the promotion of entrepreneurship. It would be necessary that the State generalizes them”. In addition to the rigidity of the laws, the considerable delays in payment deadlines, the bureaucracy and the slowness of administrative processes, a respondent pointed out that “banks grant few credits and show certain rigidity. In case of non-payment, recoveries take 1 to 2 years and are expensive”.

Finding 5: Education is undoubtedly important. On the other hand, the government should support the evolution of the entrepreneur more, both through economic and legal incentives.

Conclusion

This study has shown that entrepreneurship education is of critical importance in improving the Moroccan educational ecosystem. Hence, entrepreneurship awareness initiatives undeniably play an essential role in the life of the Moroccan entrepreneur. The choice of the methodology for this research focused on entrepreneurs, because they are the foundation of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Thus, adopted to the Moroccan context, this study allowed the authors to identify moderating variables that affect the influence of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention, such as the gender variable and the sector of activity.

On the other hand, as revealed in the theoretical part and demonstrated through the interviews conducted, it is fundamental to consider the otherramework conditions for entrepreneurship of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, which are the pillars of any entrepreneurial ecosystem and that are the following: entrepreneurial finance, government policy, government programs for entrepreneurship, technology transfer and R&D, openness of the domestic market, physical infrastructure for entrepreneurship, business and legal infrastructure for entrepreneurship, government programs to promote entrepreneurship, and culture and social norms.

Consequently, now that the results of the entrepreneurs have been obtained and analyzed, it would be interesting to study the Moroccan students’ point of view about the educational training received; a study that can be done quantitatively. Furthermore, as several researchers emphasized the possibility to become an entrepreneur through different educational policies and training, future research could focus on evaluating the allocation of public and academic resources in this area.

Bibliography

- Autio, E., Kenney, M., Mustar, P., Siegel, D. and Wright, M. (2014), “Entrepreneurial innovation ecosystems and context”, Research Policy, Vol. 43 No.7, pp. 1097-110

- Aaker D.A., Bagozzi R.P., « Unobservable Variables in Structural Equation Model With an Application in Industrial Selling », Journal of Marketing Research, vol. 16, 1979, pp. 147-158.

- Binks Martin, Ken Starkey & Christopher L. Mahon (2006) Entrepreneurship education and the business school, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 18:1, 1-18, DOI: 10.1080/09537320500520411.

- Bonaccorsi, A., Colombo, M.G., Guerini, M. and Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2013), “University specialization and new firm creation across industries”, Small Business Economics, Vol. 41 No. 4, pp. 837–863.

- Dick R. 1990., Convergent Interviewing. Interchange : Brisbane

- Drucker-Godard C., Ehlinger S. & Grenier C. (1999), «Research validity and reliability», in R.A. Thiétart et coll. (Éds.), «Research methods in management», Dunod, chap. 10, p. 257-287

- El Ganich S. and al, (2019), “Entrepreneurship training programs at the Moroccan university: contributions, limits and perspectives” Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat et de l’Innovation, Vol II N°7.

- Etzkowitz, H. and Leydesdorff, L. (2000), “The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations”. Research policy, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp.109-123.

- Fones, C and English, F. (2004). A contemporary approach to entrepreneurship education, Emerald Group Publishing, 46, pp.416-423.

- FOSS, N. J., KLEIN, P. G., 2010, «Entrepreneurial Alertness and Opportunity Discovery : Origins, Attributes, Critique », in Landström H., Lohrke F., eds, Historical Foundations of Entrepreneurship Research, E. Elgar, Cheltenham, pp. 98-120.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). «Competing paradigms in qualitative research.» In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (p. 105–117). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Henry C., Hill, F., & Leitch C. (2005). «Entrepreneurship education and training: Can entrepreneurship be taught?» Part I.Education & Training, 47(2/3), 98-112.

- Hytti, U. & O’Gorman, C., (2004). «What is “Enterprise Education”? An Analysis of the Objectivesand Methods of Enterprise Education Programmes in Four European Countries.Education +Training», 11-23.

- Jamieson, I., 1984, Schools and enterprise, in Watts, A.G. and Moran, P. (Eds). Education for Enterprise, CRAC, Ballinger, Cambridge: 19-27.

- Mário Raposo and Arminda do Paço (2011), «Entrepreneurship education: Relationship between education.»

- Huberman, A.M., & Miles, M.B. (1991). «Qualitative Data Analysis : A Methods Sourcebook.»

- KATZ, J.-A. (2003), «The Chronology and Intellectual Trajectory of American Entrepreneuriat Education », Journal of Business Venturing, 18 :2, p. 283-300.

- Kirk J., Miller M., «Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research », London, Sage, 1986.

- Langley A., « Process Thinking in Strategic Organization », Strategic Organization, août 2007, vol. 5, n° 3, pp. 271-282.

- Lee, Y.S. (1996), “Technology transfer and the research university: a search for the boundaries of university-industry collaboration”, Research Policy, Vol. 25, pp. 843-863.

- Le Louarn P., « La tendance à innover des consommateurs : analyse conceptuelle et proposition d’échelle », Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 12, 3,1997, p. 3-19.

- Markman, G.D., Phan, P.H., Balkin, D.B. and Gianiodis, P.T. (2005), “Entrepreneurship and university-based technology transfer”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 20, pp. 241–263

- Miles, M. & Huberman, M. (2003, p. 231). «Qualitative Data Analysis. » 2nd edition. From Boeck Université.

- Nair, GS & Riege, A 1995, «Using convergent interviewing to develop the research problem of post graduate thesis», Marketing Education and Researchers International, Australia.

- Olivier Toutain, Chrystelle Gaujard, Sabine Mueller, Fabienne Bornard (2014), «Dans quel Ecosystème Éducatif Entrepreneurial vous retrouvez-vous ?» Entreprendre & Innover 2014/4 (n° 23), pages 31 to 44

- Patton M., «Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods», Newbury Park, CA, Sage, 3rd edition, 2002.

- Romdane R., Conditions Cadre et Activités Entrepreneuriales : «Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions and Entrepreneurial Activity in the MENA Region: A Dynamic Panel Data Analysis», 2020.

- Schmitt C., Janssen F. and Baldegger R. (2009), Entrepreneuriat et économie, in F. Janssen (éd), «Entreprendre : Une introduction à l’entrepreneuriat», Bruxelles, De Boeck

- Shane S. et Venkataraman S., «The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research», Academy of Management Review, vol. 25, n° 1, 2000, p. 217-226.

- Solomon, G. and Fernald, L. Jr. (1991), «Trends in small business management and entrepreneurship education in the United States», Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 15(3), pp.25–40.

- Tounés, A. (2003). «Un cadre d‘analyse de l‘enseignement de l‘entrepreneuriat en France.» Cahiers de recherche de l‘Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie. Réseau Entrepreneuriat, n° 03-69, juin.

- Von Neumann J., Burks A.W., «Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata», Univ. of Illinois Press, Urbana IL, 1966.

- Wacheux F. (1996), «Méthodes Qualitatives de Recherche en Gestion», Economica.

- William Emory, Donald R. Cooper, «Business Research Methods», 1991.

- Wright, M., Clarysse, B., Lockett, A. and Binks, M. (2006), «Venture Capital And University Spin-Outs». Research Policy, Vol. 35 No. 4, pp. 481-501.

- Yin R. K., «Case Study Research : Design and Methods», 5th ed., Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage, 2014.

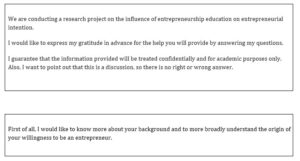

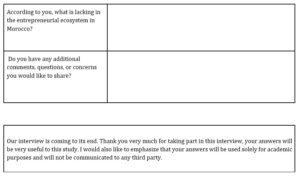

Appendix 1: Interview Guide

Presentation Of the Interviewed:

Conclusion