Economically, Poland has had a relatively successful year in 2021, especially when compared to the recessionary 2020. An essentially good macroeconomic situation has been achieved, among other reasons, due to the expansive fiscal and monetary policies, and, above all, due to the favorable external environment, which has led to an acceleration of trade between Poland and other countries.

Table 1. Economic stability indicators for Poland (2015-2021) (in percent)

* – estimated data/prognosis

Source: WEO Database, April 2021

The decline in economic growth and investment (which was relatively smaller in Europe and the world) in 2020 can primarily be attributed to the closing of Poland’s economy as part of a drastic response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the deepening of uncertainty about its future. The emergence of a negative product gap was strongly felt as it followed three consecutive years of GDP growth of above 4% due to strong consumer demand and a healthy export business climate that ultimately boosted the actual GDP over its potential. In years 2019 – 2020, we are observing greater real dynamics of exports than imports (Tab.1), resulting in a positive balance in the current account balance and an increase in the official reserve assets.

The proportion of public debt to GDP had been steadily falling to a low record of 45.7% in 2019. An increase in the deficit of the public finance sector reversed this trend in 2020. A high deficit has been also observed in 2021 but, what is even worse, it has continued to be hidden by the fiscal authorities by using creative accounting techniques more and more frequently.

It is characteristic of the period after 2018 that inflation processes accelerated, as they did in the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021. In spite of the recession caused by the Coronavirus pandemic, the average annual CPI growth rate accelerated in 2020 and reached 3.4% due to increased domestic demand. In 2021, higher inflation and the resulting depreciation of the zloty is to be expected as a result of deteriorating global raw material markets, weak crops of most agricultural produce, and increasing domestic demand. Noteworthy is that in its financial plan for 2019-2022 the government accepted the value of HICP / CPI indicators at 1.8% in 2019, and 2.5% in each of the three consecutive years. However, in the 2021-2024 plan published two years later (the publication gap was caused by the pandemic), the government evaluated these indicators at 3.1% in 2021, 2.8% in 2022, 2.6% in 2023, and 2.5% in 2024. In fact, the CPI was 3.4% while the HICP was 3.7% in 2020.

On the whole, the 2021 results for economic growth, inflation, public debt, and deficit of the public finance sector, are not as favorable as they were before the pandemic-plagued year of 2020.

-

In 2021, after breakthrough changes in the monetary policy of the National Bank of Poland (NBP) of 2020, there was a re-petrification of the Polish central bank policy. Due to the past crisis as well as to the changes it has enacted, the bank must deal with both old dilemmas as well as new ones. This is evident particularly in the area of inflation control.

At the end of 2020, Polish monetary policy experienced three major changes, which are difficult to evaluate either positively or negatively.

Firstly, in response to the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic, in March 2020 NBP (in cooperation with the government) launched a Polish quantitative easing program that involved the purchase of large amounts of bonds on the secondary market. The bond-buying program was expanded in April 2020 to include government-guaranteed debt securities (bonds issued by Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego to support the COVID-19 Counteracting Fund, as well as bonds issued by Polski Fundusz Rozwoju S.A.). The total value of bonds bought by NBP in 2020 as part of structural open market operations was PLN 107.1 billion ((in terms of the face value of the bonds) (NBP, 2020). Consequently, the structure of the central bank was gradually modified and a strange situation was overcome, in which most of the bank’s assets were in foreign currencies, while its liabilities were mostly in bonds in zlotys. The subsequent purchases of monetary gold reinforced this tendency.

It is natural to wonder about the causes and results (especially those related to inflation) of NBP’s unusual bond-buying program. It is hard to see that it was about enlarging banks’ already large liquidity. It seems clear that the main purpose of the bond purchase was to fund the government’s expansive policy of expenditures. By increasing the liquidity of commercial banks, the central bank ensured that additional debt securities could be purchased by them and possible credit expansion was possible. However, you have to remember that there is a long and bumpy road from an increase in credit capability to a realistic credit expansion, because the demand for bank loans is influenced by numerous factors that can change over time. Simply increasing the supply of financial resources owned by banks cannot expand the economy’s credit scale. By making loans to the government, companies, and households, commercial banks feed their deposit accounts. The scriptural money they create (in contrast to bank reserves) is usable for wire transfers or credit card payments. The level of market interest rates is particularly important here. Even with low interest rates, Polish companies with large amounts of funds available in their accounts have not shown a significant demand for new loans for a long time.

As far as the households’ demand for loans is concerned, the picture is somewhat different. Recent low interest rates have led to a surge in consumer loans and a real explosion in mortgage demand. On the one hand, the situation accelerates inflation processes (1), but, on the other, it is a form of unique competition when banks decide whether to extend loans to the general public or buy government bonds. (Banks would not buy government bonds if they were less profitable, despite taking a smaller market risk.) As a result of adopting historically low interest rates and executing specifically designed buy-backs of bonds issued or guaranteed by the state, the central bank made the choice for the banks. Bonds purchased on the primary market were resold to NBP by the banks. The funds obtained from these transactions were reinvested in state-issued bonds, which were either deposited in their current accounts with the central bank or in the form of overnight deposits, or reinvested in NBP bills.

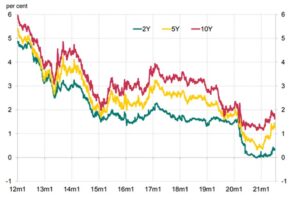

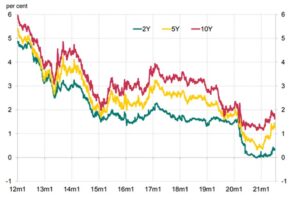

The bond purchases carried out by NBP on the secondary market directly raised their market prices and lowered their yields. The Polish central bank, thereby, strengthened its control over interest rates on the financial market, whether short-term rates that are used on the overnight interbank market (i.e., loans granted by banks to one another for a day) as well as the long-term ones that are used on the capital market. In 2020, NBP managed to successfully lower the yields on government bonds (Fig. 1). However, to achieve this, the central bank was required to artificially maintain its real negative interest rates with increasing modules, causing the entire economy to suffer, especially in the area of inflation. Moreover, the yields started increasing at the beginning of 2021, which could indicate that the extraordinary formula to support the expansive financial policy of the government has run out. Clearly, the lower interest rates and higher bond prices enabled an increased public debt to be financed while at the same time lowering the average cost of servicing it.

Fig. 1. Yields on Polish government bonds nominated in zlotys (January 2012 – May 2021)

Source: NBP, 2021

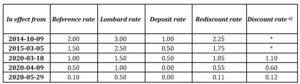

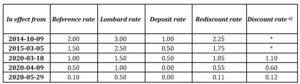

The second development was an update to interest rate policy in spring 2020. The NBP’s basic interest rate was changed three times by the Monetary Policy Council (MPC) in March, April, and May to reach the lowest ever level after five years of stabilization (Tab. 2). This represented a definite departure from the central bank’s policy of stabilizing interest rates in order to fuel inflation-related pressures. From March 5, 2015, to March 18, 2020, Poland’s monetary authorities kept the reference, lombard, deposit, and rediscount rates constant at 1.5%, 2.5%, 0.5%, and 1.75% respectively. Such a long period of the central bank’s interest rate freeze can not be rationally justified when we take the changing economic landscape into consideration. It is hard to justify the claim of the necessity to provide financial stability to businesses when we consider how highly volatile the other economic parameters were, such as the fluctuating economic growth and the increasing domestic inflation developments. As denoted by the end of this period, there were signs of rising inflation, so as dictated by orthodox monetary policy, a rise in interest rates was to be expected. However, what followed was a significant drop in rates caused by the need to counteract economic collapse caused by the Coronavirus pandemic and to cooperate with the government as part of the government’s economic recovery plan (to support its subsequent anti-crisis shield programs).

Table 2. NBP interest rates (2015 – 2021)

a) the discount rate was introduced due to the NBP’s restitution of a promissory credit that had been previously used in 2010.

Source: NBP data

Poland’s interest rate policy featured positive real interest rates until mid-2017, and the 2020 changes marked a departure from that policy. Increasing the negative module of the NBP’s real interest rates was equivalent to the bank allowing inflation to rise further with all the consequences for the savings rate, debt servicing processes, and the value of the domestic currency. In practice, this meant the suspension of the direct inflation targeting strategy which had been formally applicable since 1998.

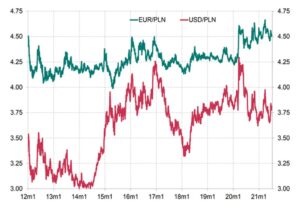

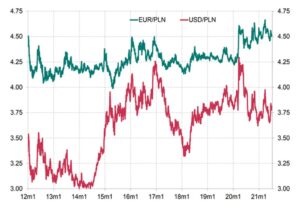

Thirdly, at the end of 2020, Poland’s monetary authorities switched from the liquid exchange rate regime to controlled floating using verbal interventions and foreign currency purchases aimed to weaken the zloty exchange rate. The onset of the pandemic and the accompanying rise in aversion in global financial markets to the risk associated with emerging markets also contributed to the weakening of the zloty against major currencies. After an improved sentiment on the financial markets, the zloty grew stronger, particularly against the dollar, while the worsening pandemic-driven conditions made the zloty weaker and increased the EUR/PLN rate above its spring levels. In reality, however, the zloty’s adjustment to the global disruption caused by the pandemic and the NBP’s easing of its monetary policy was relatively limited, due in part to Poland’s successful foreign trade. At the end of October 2020, the zloty exchange rate began to quickly strengthen against the US dollar. This resulted in the central bank’s first foreign exchange interventions in years in December 2020, the scope of which was not disclosed. According to the Governor of NBP, the interventions were intended to combat the procyclical (or pre-recessionary, at the time) strengthening of the zloty exchange rate as well as to reinforce the growth-oriented influence of the quantitative easing on Poland’s economy. One must not forget, however, that the picture is somewhat different when it comes to the euro which is the most important foreign currency in Poland’s financial exchange with other countries (see Fig. 2). The exchange rate of the euro had been growing gradually, and at the end of the year exceeded PLN 4.60. In 2020, the average exchange rate of the euro (EUR/PLN) was PLN 4.44, while the average exchange rate of the US dollar (USD/PLN) was PLN 3.90 (2). In 2021, the zloty exchange rate is still subject to sharp fluctuations, with a tendency to the nominal depreciation.

Fig. 2. Nominal exchange rate of the euro and the US dollar in zloty (January 2012 – May 2021)

Source: NBP, 2021, p. 44 (Bloomberg data)

-

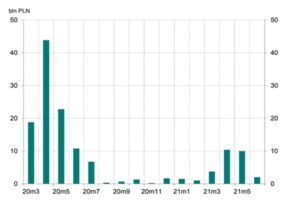

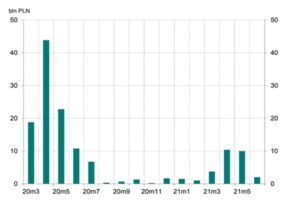

The main problem with Poland’s monetary policy that the Polish monetary authorities have not been able to handle during the last 25 years is the surplus liquidity of the banking system, which has negatively affected NBP’s ability to use its financial instruments effectively. Over the past few quarters, the surplus liquidity has grown significantly. A clear indication of this trend is coming from the results in 2020, in which there has been an increase in the surplus liquidity in the banking sector as a result of NBP activities. According to NBP data, the level of funds that remain at the banking sector’s disposal, in excess of the required reserve averaged PLN 183.8 million in December 2020 and was more than twice the size of the one in the corresponding period in 2019. A major factor in the increase in the liquidity surplus (of almost PLN 111.9 billion – see Figure 3) was the purchases of debt securities on the secondary market carried out by NBP as part of its structural open market operations since March 2020.

Fig. 3: Structural open market operations conducted by NBP in nominal value, monthly (March 2020 – May 2021)

Source: NBP, 2021, p. 43 (NBP data)

When there is a limited pool of new net loans (especially investment credits), additional liquidity from bond purchases supplies most of the excess liquidity of the banking sector. The decision to reduce the required reserve from 3.5% to 0.5% had the same effect. Another factor contributing to the higher liquidity surplus in the banking sector was the foreign exchange transactions conducted by NBP, including the purchase of foreign currency from the Ministry of Finance. Increases in foreign currency sales to the European Commission partially limited this increase. NBP’s inclination to purchase foreign currency over its sales resulted in a notable increase in the funds at the disposal of the banking sector. The excess liquidity of the banking sector was curbed by the significant rise in currency in circulation, primarily at the beginning of the pandemic, decreasing the amount of funds available to the banking sector by almost PLN 82 billion.

The year 2020 saw an increase in the average balance of the short-term monetary policy operations due to an increase in liquidity surplus in the banking sector. Other than investments in NBP bills (as part of the main and fine-tuning open market operations), the remaining funds of the banking sector were held on current and overnight accounts with NBP. Among the primary evidence of growing surplus liquidity in Poland’s banking system in 2020 was a larger scale of these surpluses than in previous years, or the banks’ insufficient use of lombard credit.

On the basis of information available at mid-2021, it is possible to speculate that Poland’s banking system’s surplus liquidity continues to grow. According to approximate estimates, approximately PLN 250 billion worth of commercial banks’ assets is stored in accounts with NBPs or invested in NBP bills as of July 1, 2021, with an expected increase. What is worse, the central bank does not have easy-to-use instruments that would reduce the surplus liquidity. Possibly because of this, NBP has been trying to increase cash transactions for several months, which is in contrast with the development of payment systems around the world.

-

The required reserve system contributes to the stabilization of short-term interest rates as it absorbs a substantial portion of the banking system’s liquidity surplus. On May 29, 2020, the interest rate on required reserves was lowered from 0.5% to 0.1% (i.e., to a new level of the NBP reference rate), which had a slight impact on decreasing the speed at which surplus liquidity was generated. As far as its effect on the banking system’s liquidity surplus is concerned, lowering the interest rate on required reserves is a positive development, whereas lowering the required reserves ratio is counterproductive.

In addition to the above-mentioned structural operations of the open market and the changes in the minimum reserves policy, the basic instruments affecting the situation on the Polish interbank market were the NBP’s main open market operations and the fine-tuning of those operations. By offering these operations, the central bank gave commercial banks the ability to balance their liquidity positions during the required reserve maintenance periods. Their profitability was defined by the NBP reference rate which changed on three occasions in 2020. This profitability directly affected the price of money used in transactions between banks (the POLONIA rate). For many years, the MPC’s primary objective has been to maintain the POLONIA rate at the NBP reference rate. In conditions of growing surplus liquidity, the POLONIA rate is not a reliable indicator for the interest rates policy because it usually reaches a higher level than that of the NBP reference rate, while its deviation from the reference rate is rather modest. It was demonstrated in 2020 when the POLONIA rate stayed at a lower level almost throughout the entire year than a continuously decreasing reference rate, while the deviations also gradually decreased over time.

-

It can be argued that, in conditions of persistent structural surplus liquidity of Poland’s banking system, it would have been difficult to expect interest rate policy to be eased at the turn of 2019/2020, especially so when we consider the fact that, beside the level of real interest rate, the restrictive nature of the monetary policy regime also tends to be decided by the real national currency exchange rate (Rosati, 2017, p. 490). Keeping the central bank’s interest rates unchanged for more than five years was, at the time, understood as an expression of a narrow concern confined to domestic monetary stability (primarily measured in terms of low inflation). On the other hand, at the end of 2019, it seemed risky to assume that NBP interest rates would not increase in view of the three-year-long positive output and inflation that had been forecast to increase in the near future. However, from both a theoretical and a practical perspective, tightening the monetary policy amidst a weakening economy was in conflict with the need to support the country’s economic growth. The situation was obvious in an economic collapse caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The NBP interest rates were unexpectedly lowered three times in spring 2020.

As we look toward the future, the zloty’s exchange rate is unlikely to stabilize or appreciate given the uncertainty about the relevance of domestic policy, increased inflation, and inevitable fluctuations in global financial markets. What could be expected, though, is a greater changeability of the zloty exchange rate with all its consequences on the level of the domestic price levels, the cost of the servicing of foreign debt, and the cost-effectiveness of exports and imports. The exchange rate policy affects not only such things as various payment balance sheet positions, the valuation of foreign public and private debt, or their servicing cost in złoty, but also exerts an enormous influence on Poland’s capital account balance with other countries in terms of direct and indirect investments (portfolio investments). Thus, our opinion is that Poland requires an active exchange policy – frequent and deep interventions in the foreign exchange market.

Even in the midst of pure floating, the monetary policy of MPP exerts an essential, though indirect, influence on the zloty exchange rate. Due to currency interventions at the end of 2020, MPP’s policy directly contributed to the weakening of the national currency. The Polish monetary authorities had worried that lowering interest rates and depreciating the zloty would destabilize the demand for domestic debt papers (especially from foreign investors who constituted a significant portion of Polish bond buyers) until the spring of 2020. It is not only the number of interests they receive that interest investors from abroad are interested in, but also the rate at which profits and capital are transferred from their portfolio investments abroad (or, to be more precise, in comparison with the initial exchange rate). Thus, NBP’s foreign currency purchases in December 2020 were a surprise and could have signaled a change in the authorities’ attitude toward foreign bond buyers. Instead, there was a case for the low zloty exchange rate to favor Polish exporters, enabling them to quickly increase export production and therefore recover from the pandemic-induced recession. A low nominal national currency exchange rate does indeed tend to stimulate exports, but at the same time inhibits import growth, as was evident from spring 2018 to spring 2020. Polish exports were quite satisfactory during the remaining months of the “Covid-19” year, despite periodic increases in the zloty’s exchange rate against foreign currencies. The reason was that we have become familiar with the fact that a number of factors determine the country’s export success (including, to some extent, exchange policy). The NBP’s weakening of the zloty exchange rate could be considered an attempt to hold the real national currency exchange rate (which, in the preceding months, had appreciated due to rapidly growing inflation) steady at a level higher than major trading partners by a couple of percentage points. However, this is a very sophisticated reason, and a difficult one to balance. Meanwhile, the low exchange rate inevitably leads to fueling inflationary pressure, which consequently may cause increased import demand.

-

The basic premise of changing foreign currency policy at the end of 2020 was to maximize NBP’s profits from positive exchange differences. Over the course of many years, NBP’s financial performance has been determined primarily by the positive results of managing foreign exchange reserves which, until March 2020, constituted almost 100% of NBP assets, and by the negative results of its monetary policy resulting from the surplus liquidity in the banking sector. Narodowy Bank Polski earned a profit of over PLN 9.3 billion in 2020, representing a 19% increase over the previous year. As outlined in the NBP Act, the profit was distributed in the form of almost PLN 8.9 billion for the public budget (95% of its amount) and PLN 0.4 billion for the NBP reserve fund (5% of its amount).

Monetary policy changes helped impact the government’s finances significantly by facilitating the funding of increased budget expenditures through an increase in tax revenues and a reduction in public debt costs. All this, however, took place at the expense of increased inflation. A spiral in pricing and wages is also on the horizon.

As we observe the changes in the opposite direction than that expected by theoreticians and practitioners alike, the question arises as to whether the Polish monetary authorities are fulfilling their constitutional mandate, or duty, to preserve the value of the Polish currency. In recent months, it has been its domestic purchasing power, and in relation to foreign currencies.

-

Poland’s finances are also influenced by external conditions, even though the government’s expansive budget poses the greatest threat to the state of the Polish financial system (including the monetary system). NBP pays close attention to the condition of its balance of payments, to how the country’s debt relative to the rest of the world is structured, and to Poland’s International Investment Position. The condition of the bank’s balance of payments is determined by the condition of its current account balance, which is heavily influenced by the net export level of goods and services. This raises the question of whether we are dealing with a relatively permanent positive development trend in Polish foreign trade, or whether we will see a deficit in the foreign trade volume associated with an increase in domestic demand and potential deterioration of export opportunities. The high deficit in the primary income balance (one of the indicators of global competitiveness), on the other hand, must be a source of great concern for many.

Despite the increased uncertainty around Poland resulting from the expansive expenditure policy of the new authorities and the instability of the legal system, Poland’s good macroeconomic condition has resulted in the improvement of the financial account balance in recent quarters. What is important, recent years have seen a stabilization in the influx of direct foreign investments of EUR 13-14 billion annually. As for portfolio investments, we are observing an exodus of foreign portfolio investors, which is a result of reduced yields on Polish bonds (or, an increase in their price resulting from an inflated assessment of Polish credit ratings). As a result, Poland began reducing the cost of incurring debt and servicing it.

An improvement of the financial account balance made it possible to increase official reserve assets, which amounted to EUR 125.6 billion at the end of 2020. In addition, an increase in these assets despite a simultaneous increase in the value of imports of goods and services meant that the ratio of imports of goods and services was raised to over six months. According to NBP data on Poland’s balance of payments, in mid-2021, Polish receivables in exchangeable currencies exceeded EUR 120 billion, which was mostly the result of a relatively high current and capital account balance and currency exchange rate fluctuations. It is worth noting that the experience of many countries shows that even large currency reserves are not sufficient to prevent currency panics or speculative attacks, as well as destabilization of the financial system.

-

Poland belongs to countries seriously indebted to non-residents. According to NBP data, Poland’s gross foreign debt has been declining for several years. By the end of 2020, it totaled EUR 303.7 billion ($ 372.9 billion), and its share in the GDP decreased to 60% primarily because the economic growth rate accelerated. At the same time, Poland’s international net investment position has improved, and its share in GDP at the end of 2020 amounted to -44%. Since 2015, this share hasn’t exceeded the threshold recognized by financiers as dangerous, namely -65% of GDP, with a clear tendency to improve. On the other hand, in the EU’s safety indicator set (the so-called scoreboard), the threshold was set at a more demanding level of -35%, which is why Poland’s negative international net investment position has to be regarded as unfavorable, the more it appears that external financing will prove more difficult in the future.

-

Based on the experiences of the Great Recession, the eurozone crisis, and the pandemic-induced crisis as well as how those crises were handled, it becomes clear that remaining outside a larger and stronger currency area (even for a medium-sized country) is not only viewed as anachronistic in a globalized world but is also increasingly costlier and riskier. In order to deter or stabilize currency exchange rates, one needs to maintain large currency reserves, but the costs tend to be higher than the benefits of independent monetary policy and a currency depreciation option (generally overrated).

In recent years, as part of the “pragmatic realism” policy mix pertaining to the eurozone integration, there was a significant shift in the Polish authorities’ focus from nominal convergence processes to real convergence processes. This, coupled with the negative view of the European currency held by the public, calls into question Poland’s speedy entry into the Economic and Monetary Union. As the central bank has challenged a quick entry into the eurozone, it has for the first time publicly supported both those opposing deeper European integration and the banking sector, whose interests have not always aligned with the needs of the country’s economy. The latter applies equally to how banking revenues should be structured, and how banks should be supervised.

Poland is legally and internationally committed to introducing a single European currency as soon as the macroeconomic situation of the country permits, according to the Accession Treaty of 2003. Entering the third stage of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), or, becoming a Full Member, should occur once the nominal convergence criteria have been met. According to Convergence Report 2020 (3), in a two-year reference period from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2020, Poland met three out of the six criteria for nominal convergence – share of government deficit in GDP, government debt to GDP ratio, and long-term interest rates. Criteria not met included inflation (as measured by Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices), exchange rates, and national legislation being in compliance with relevant EU law. A significant increase in the domestic inflation rate is responsible for the first unmet criterion, participation in ERM II is required for the second while monetary legislation must be changed to meet the third one. It may be difficult to maintain low yields on Polish bonds in the future if the financial market’s sentiment toward emerging markets (including Poland) deteriorates. In addition, the long-term budget consequences of fighting the Coronavirus pandemic may result in Poland failing to meet both fiscal nominal convergence criteria in the coming years.

-

Undoubtedly, the need to combat the crisis caused by COVID-19 prompted the central administration and monetary authorities to increase their cooperation. What is more, it also necessitated a fundamental change (but not necessarily a sufficiently effective one) in the existing monetary policy. The Monetary Policy Council remained under the influence of one political party, thus being unable to deal with the emerging challenges, in particular when it came to ensuring a stable exchange rate for the Polish currency. When we assess the Council’s activities, one may risk saying that it very poorly managed to increase the impact of its monetary policy on the acceleration of economic growth, to improve the situation in the balance of payments or the conditions on the labor market. The too-long interest rate freeze, coupled with the persisting surplus liquidity in the banking system, cause the country’s socio-economic development to take place autonomously, and somewhat independently of the monetary authorities. The monetary policy, which is still formally governed by the direct inflation targeting strategy (BCI), was gradually eased from mid-2017, which, combined with an expansive policy of government spending, intensified inflation processes in the second half of 2019.

For NBP to create a sophisticated market-oriented monetary system and a modern central banking system, many institutional changes must be implemented and its monetary concept must be revised. In light of both national and foreign experiences over the last years, it is imperative to depart from the BCI strategy and rethink the primary purpose of NBP’s monetary policy. Rather than focusing on unrealistically defined inflation targets, Poland’s monetary authorities should pay more attention to the value of money as well as to the stability and quality of the country’s financial system.

End notes

- the second half of 2019, as well as at the beginning of 2020, inflation had already risen, and after March 2021, it had risen even more in connection with the expansive policy of government expenditures.

- see Wieloletni plan finansowy państwa na lata 2021-2024 [Multiannual financial Plan for 2021-2024], p. 9.

- see Convergence Report 2020, ECB Eurosystem, June 2020, pp. 60-70.

References

- IMF: World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database. [online] Available at: [Accessed 18 September 2021].

- European Central Bank, 2021. Convergence Report. [online] European Central Bank. Available at: [Accessed 18 September 2021].

- NBP, 2019. Międzynarodowa pozycja inwestycyjna Polski w 2018 r. [Poland’s International Investment Position in 2018]. Warsaw: Narodowy Bank Polski.

- NBP, 2021. Sprawozdanie z wykonania założeń polityki pieniężnej na rok 2020 [Report on monetary policy in 2020]. Warsaw: Narodowy bBank Polski, Monetary Policy Council, p. 8.

- NBP, July 2021. Raport o inflacji [Inflation Report]. Warsaw: Narodowy Bank Polski, Monetary Policy Council, p. 44.

- Rosati, D., 2017. Polityka gospodarcza. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH.

- Wieloletni plan finansowy państwa na lata 2019-2022 [Multiannual financial Plan of the state for the years 2019 to 2022] (M.P. item 429, 2019)

- Wieloletni plan finansowy państwa na lata 2021-2024 [Multiannual financial Pplan of the state for the years 2021 to 2024] (M.P. item 450, 2021)