Introduction

Family firms play an important role in leading economic growth throughout the world (Chua, Chrisman, and Sharma, 1999; Sacristán-Navarro, Gómez-Ansón, and Cabeza-García, 2011). This statement also relates to Poland, as in 2009, according to PARP (The Polish Agency for Enterprise Development) family businesses accounted for 36% of the SME sector, whilst the share of family enterprises decreases along with the growth of the enterprise: among micro-enterprises, family companies account for 38%, small companies 28%, and medium-sized companies 14%. It is estimated that family businesses produce at least 10.4% of the total Polish GDP and employ about 21% of the total employed by the SME sector.

Family enterprises are often associated with small and medium-sized enterprises. The cross-sectional quantitative research on family businesses in Poland was very limited and usually concentrated on the SME sector. Considering the fact that there is no single definition of the term “family enterprise” and no statistics specific for family businesses, the number and importance of family businesses can only be estimated, especially concerning large family business.

In family enterprises, resources are identified as family assets, which seem to create strong relationships between the company and the family. A strategic advantage of a family firm is the result of having unique resources, such as social, human or financial capital. Social capital in family businesses, based on strong ties and mutual trust, speeds up the flow of information and allows reducing the transaction costs. This increases the flexibility of these entities and enables quick adaptation to changes in the environment. The unique relationship between the family and the company’s resources, treated as family property, leads to prudent decisions and avoidance of high risk in the business (Klimek, 2014; Leszczewska, 2016).

Family business may have unique perspectives of socially responsible behavior due to the family involvement and ties to the community and their commitment to uphold the business. Some researchers argue that the strong roots in the local community have an important impact on their higher interest in socially responsible activities (López-Cózar, 2014). Other scholars claim that it is unclear to establish if family values influence the greater popularity of CSR among family businesses (Zulkifli, 2011).

Therefore, the discussion on the social responsibility in family business should be placed in the context of their unique resources and special relationships between the family and the business. The scientific discussion regarding CSR is definitely ongoing also in Poland, but there is still little evidence on the features of the socially responsible approach in family owned companies.

Definitions of the Family Business

Family firms are a crucial part of the business landscape and have played a significant role in the economies for years. The study of La Porta, et al., (1999) indicates that families control 53% of publicly traded firms in 27 countries. The research conducted in the USA by the Family Firm Institute (2014) shows that family businesses account for 80% of all enterprises and create nearly 50% of GDP. Similar evidence can be found in the emerging-markets. Claessens, Djankov, and Lang (2000) state that a significant number of firms are owned and managed by controlling families in East Asian emerging-market countries. Even though Western European countries have a different corporate culture and organization, here also family businesses dominate in the economy. Morck and Yeung (2004) confirm these results for other countries, such as Germany or Spain, where family enterprises constitute approx. 60%. Italy, Sweden and Germany show more vivid evidence that the percentage of family controlled firms make up more than 90 percent of all firms in these countries.

Despite the important role of family entrepreneurship in the economy, there are still serious problems with defining a family firm. This may be due to the existence of a very diversified research group as each family business has its own history, culture and specifics that differ in various ways. Moreover, the legal form, size, type of activity, length of operation or development stage may affect them greatly. Although in 1989 Handler stated that “defining family businesses is the first and the most obvious challenge that family business researchers have to face”, after nearly 30 years the challenge still remains.

It is generally agreed that family involvement in the business is what makes the family business unique. Based on the subject literature review, it is said that any relation between the family and the business is sufficient to conduct a family business. An example is given by Davis who defined the family business as a structure with the presence of interactions between family and business. Handler (1989) claims that the family involvement refers to ownership and management. Churchill and Hatten (1987) believe that the involvement also includes the existence of a family successor. One more example is the definition provided by Beckhard and Dyer (1983) that a family business is the system that includes the business, the family, the founder and such linking organizations as the board of directors. Despite the existence of many definitions, a family business is connected to three basic terms. These are family, business and ownership (Davis and Harveston, 1998).

Family companies have also been defined in a variety of ways in the literature including the degree of family ownership, management by family members, interdependency of systems, and intention to transfer to the family (Litz 1995). To address the degree of involvement in family business, Astrachan and Shanker (2003) offer a broad definition that includes control over the strategic direction of the firm and direct involvement in daily operational issues.

The main problem in defining family business is the broad variation of the examined subject. Under the heading of family businesses are small, medium, and large companies; family-owned, family-managed, family-controlled businesses subsumed; and founder companies that are “potential family businesses” but clearly not non-family businesses. That is why, according to Klein (2000), the decision whether to classify a business as a family business should be made with the data based on the definition and not on what a researcher, company, and/or family members decide. In addition, the definition has to draw a clear boundary between family and non-family businesses and must classify different types of family businesses.

In 2007, the group of experts of the EU Member States within the framework of Final Report specified the so-called European definition of family businesses (EC, 2009). The definition has been adopted by the European Commission as follows: A firm of any size is a family business, if:

- The majority of decision-making rights is in the possession of the natural person(s) who established the firm, or in the possession of the natural person(s) who has/have acquired the share capital of the firm, or in the possession of their spouses, parents, child or children’s direct heirs.

- The majority of decision-making rights are direct or indirect.

- At least one representative of the family or kin is formally involved in the governance of the firm.

- Listed companies meet the definition of family enterprise if the person who established or acquired the firm (share capital) or their families or descendants possess 25 percent of the decision-making rights mandated by their share capital.

The research on Polish large family businesses, therefore, is based on a family-involvement perspective defining family businesses as those that are owned and managed by one or more family members. In order to accurately determine this influence, a 25 percentage share of the family in the ownership or in the decision-making rights has been applied.

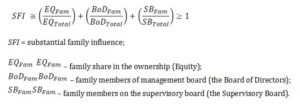

According to Klein (2000) substantial family influence is considered if the family either owns the complete stock or, if not, the lack of influence in ownership is balanced through either influence through corporate governance (percentage of seats in the Supervisory board held by family members), or influence through management (percentage of family members in the top management team). For a business to be a family business, some shares must be held within the family.

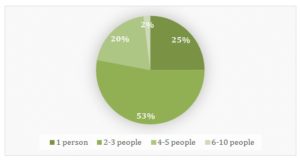

The SFI indicates a family’s influence on the business through ownership, management, and/or governance. In this article SFI is used to classify a business as a family business. The value of the indicator ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 means the entities with a weak family influence, whilst the value of 1-1.5 defines the average family impact, and the value above 1.5 identifies companies with a strong family influence (Giovannini, 2010).

Scholars believe that family companies have unique characteristics derived from the pattern of ownership, succession and governance. These characteristics have an impact on the strategic process thereby affecting the performance of those firms (Anderson and Reeb, 2003; Carney, 2005). It is understood that in a family business, family members will influence the business. This is especially true if the owner or manager of the business is also a member of the family. In studies that develop this concept, family ownership and/or management of the business are considered to distinguish family businesses from other businesses or to convey that the family has the power to lead its own business. In family business, spouses of members of the family provide both tangible and intangible contributions to business issues and, in certain situations, they even have decision-making power (Ayranci, 2014).

The influence of family should also be considered in the context of agency relationships. Originally, agency problems were not watched in family firms because of their unified ownership and management, resulting in an environment where interests are aligned and monitoring is unnecessary (Chrisman, Chua, and Sharma, 2005; Karra, Tracey, and Phillips, 2006). Since that time, family firm scholars have developed theoretical borders by highlighting previously overlooked agency problems and conflicts. For instance, family member managers tend to be more selfless as they are rarely motivated by financial incentives, thus, family businesses managed by the family can be more effective and productive compared to non-family businesses (Madison, Holt, Kellermanns, and Ranft, 2016).

A family firm is seen as a unique construct. To underline capabilities that are unique to the family’s involvement and interactions in the business, the theory of “familiness” has been identified. Familiness means “resources and capabilities that are unique to the family’s involvement and interactions in the business” (Pearson, 2008), thus it is closely related to social capital. This is the familiness as the source of competitive advantage of family entities. According to Pearson and other authors, familiness brings about positive outcomes when family is involved in the business. It is the regular interaction between family, business and individual family members that make these resources and capabilities unique (Popowska, 2015).

Corporate Social Responsibility of Family Businesses

The first definition of CSR was presented by Bowen (1953, p. 6), who stressed the ‘‘obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society.” This perspective developed in response to the progressively widening range of activities implemented by large companies that had potential and severe repercussions on the welfare and general conditions of society. Institutional interpretation made by the European Union defines CSR as ‘‘a concept whereby companies decide voluntarily to contribute to a better society and a cleaner environment’’ (CEC, 2001) and ‘‘a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis’’ (CEC, 2006). Firms are encouraged to consider their responsibilities toward several stakeholders with the goal of integrating economic, social, and environmental concerns into their strategies, their management tools, and their activities, going beyond simple compliance. Over the years, scientists have established certain CSR principles. Firstly, socially responsible companies have to act “voluntarily” to adapt to CSR paradigms; secondly, the relationship between “business and society” have to be long-term (Russo, 2009). Being a Socially Responsible Company requires having product/service quality programs in order to achieve maximum customer satisfaction, providing safe and healthy work conditions as a basis for promoting the well-being of their employees and environmental management practices (Bakanauskiene, 2016).

Researchers argue about the existing differences between family firms and non-family businesses with regards to CSR. Some scholars have suggested that family firms are not likely to act in a socially responsible manner, whilst others have indicated that socially responsible behavior on the part of the family firm protects the family’s assets. Family businesses have certain characteristics that make them different from non-family ones in terms of objectives, organizational structure, culture and strategic behavior (Chrisman and Chua, 2005; López-Cózar and Hilliard, 2014). Uhlaner, Goor-Balk and Masurel (2004), in their work on family businesses in the Netherlands, found that the family nature favors the establishment of a special relationship with workers, customers and suppliers. Meanwhile, Lopez-Iturriaga, López-de -Foronda and MartinCruz (2009) conducted a study with companies from five European countries, and conclude that family-owned companies are more likely to focus on CSR than those with other investors (López-Cózar, 2015).

The prevailing assumption is that a family business ownership structure, thanks to long term community orientation and shared vision, would be naturally ethical and socially responsible. Family business may have unique perspectives of socially responsible behavior due to family involvement and ties to the community and their commitment to keep the business. Some researchers argue that strong roots in the local community have an important impact on their higher interest in socially responsible activities (López-Cózar and Hilliard, 2014). At the same time, some scholars argue that it is unclear to ascertain that family values that could be inherent in the family business by nature pave the way to CSR greater popularity among family businesses (Zulkifli, Hasan, Saleh, and Zainal, 2011), while others claim that differences in approaches towards CSR are deeply rooted in the family and that the beliefs and value systems of entrepreneurs play a fundamental role in shaping a sustainable corporate strategy (Perrini and Minoja, 2008; Popowska, 2017). Graafland suggest a positive relationship between a company size and the use of CSR, in particular, the positive impact on the use of several instruments, like code of conduct, ISO certification, social reporting, social handbook and confidential person (Graafland, 2003).

Family firms very often prioritize non-financial goals that do not follow the traditional business logic. Therefore, they are more inclined to be socially oriented even if this orientation does not generate economic benefits (Berrone, 2012; Popowska, 2017).

Another important topic of family firm on CSR studies is examining the relationship between CSR and potential business benefits, especially the financial performance. Some researchers claim that there exists a positive influence of the CSR orientation on the financial performance (Elbaz and Laguir, 2014; Campbell and Park 2016), when others deny the existence of such effect (Madorran and Garcia 2016). According to Perrini, the importance of the relationship between social performance and financial performance depends to some extent on the kind of competitive strategy that a company has selected. There are many contrasting studies: some of them conclude that the relationship between the social and financial performance may be varied according to the industry which it involved, whilst others report the absence of such correlation (Perrini and Minoja, 2008; Popowska, 2017).

To date, there have been no studies where researchers explicitly investigated CSR for large family businesses in Poland. With regard to research on Polish family businesses in general, there are few (among others Winnicka-Popczyk 2016; Leszczewska 2016; Koładkiewicz, 2013; Popczy, 2013; Safin, 2012) and fragmentary research about the application of CSR mechanisms in family-owned business from SMEs. Taking into consideration the limited number of research analyses of CSR and family firms and the importance of family businesses in the United States (Astrachan, 2003) and around the world (Poza, 2010), CSR for large family businesses in Poland was investigated through the following research questions:

- Do family businesses in Poland undertake any philanthropic activity?

- Do family firms in Poland value corporate social responsibility?

- How do family businesses engage in corporate social responsibility, what actions do they take on?

- How does philanthropic activity affect family firm performance?

Corporate Social Responsibility in Polish Large Family Business – Empirical Results

The survey on large family businesses, conducted in 2010-2015, mainly concerned supervisory and control mechanisms of family business. However, some questions also identified the attitude of family enterprises toward CSR. A survey questionnaire was used and the entire population of large private enterprises operating in Poland was examined. Then a group of family enterprises was separated, calculating the share of these entities in the economy at the level of 18%. The next stage of the research was to direct the survey to the entire group of large family businesses in Poland (203 entities), achieved feedback was at the level of 24%, i.e., the research group was created by 49 entities.

Most of the surveyed enterprises conducted business activities in the form of a capital company (35% limited company and 39% stock company) and operated in industry (55%). A major part of surveyed entities has operated on the market for over 10 years (86%), and 9 of all companies for over 30 years (18%). Over 80% of the surveyed family enterprises employ from 250 to 1000 employees and less than 20% more than 1000 employees (41; 9 entities).

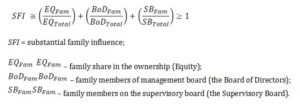

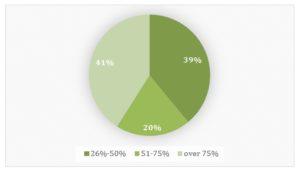

Then the family ownership was examined in large family businesses with the following results:

- nearly 40% of companies are those where the family has over 25% of shares and not more than 50%;

- over 20% of family firms have family ownership up to 75%;

- and over 40% of researched entities have shares in excess of 75%.

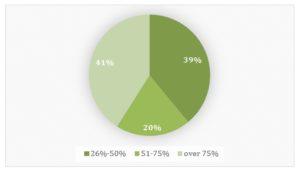

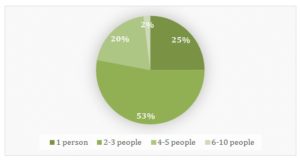

Family property was in the hands of 1-3 people and in almost 60% of cases it was a share of more than 50% of the company’s property (Figure 1-2).

Fig. 1: Share of family business ownership in the hands of the family

Source: own calculation

Fig. 2: The number of people who had shares in family ownership

Source: own calculation

In the surveyed family, the family’s shares were very concentrated despite operating on a large scale. It can be concluded that the familiness affects the concentration of ownership in the hands of a limited number of people, the family members.

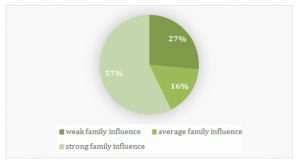

According to SFI formula (Substantial Family Influence, Klein, 2000), the family influence on corporate governance was investigated. It was found that in more than 70% of the entities, the family control was medium or strong. The values of the family control indicator SFI ranged from 0.63-2.87 (M = 1.55, SD = 0.59). The distribution of this value did not differ from the normal distribution, Z = 0.77, p> 0.05. In fig. 3 the frequency distribution for the level of the family control indicator is shown

Fig. 3: The level of the SFI indicator

Source: own calculation

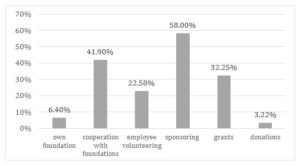

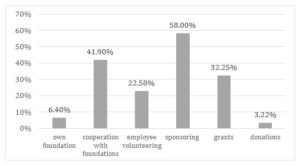

In the next part of the family business research the questions about philanthropic activity were asked: has the company undertaken any philanthropic actions in the last three years, if any, what kind? Over 60% of respondents admit that their family firm conducts philanthropic activities. In Fig. 4, the types of these activities are demonstrated.

Fig. 4: The types of the philanthropic activity

Source: own calculation

Out of 31 entities that conduct philanthropic activities, 18 sponsor events (over 50%), 13 entities cooperate with foundations (nearly 42%) and 10 give grants (over 30% of respondents of family businesses). Only two of researched companies have their own foundation and only one donates money for charity.

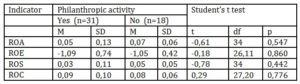

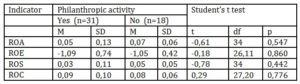

The financial situation of the surveyed family enterprises was estimated using the ROA, ROE, ROS, ROC indicators. Then a series of hypotheses was tested regarding activities towards CSR for family business performance. In Table 1 a comparison of average values of financial ratios for 2013 for companies which in the last three years undertook some charity activities and for companies that did not undertake philanthropic activities in the last three years was shown. The list was supplemented with the Student’s t test results for independent samples.

Table 1

Source: own calculation

There was no statistically significant difference between companies undertaking philanthropic activities and those not undertaking philanthropic activities and the influence on their financial performance.

Conclusion

Corporate social responsibility is one of the trends that have a significant impact on the development and strategic behavior of modern business entities. Currently, it is a popular concept emphasizing the role of economic entities in socio-economic development, but its use in the activities of Polish family enterprises has so far been the object of scientific research very seldom. Previous Polish scientific publications on the idea of CSR in family enterprises contained a description of CSR practice in selected entities or were of a theoretical nature, and only few showed the results of qualitative research.

The aim of the empirical studies carried out by the author was to supplement this research gap. The study aimed assessed the willingness to take socially responsible actions by family businesses. It seemed that in connection with the specific character of family businesses indicated in the subject literature, their activity in the field of CSR would be high. The presented results showed what philanthropic activities are undertaken by large family businesses and how they affect or rather do not affect their financial results.

According to the results of the questionnaire responded by large family businesses, the majority of them undertake philanthropic activities. But what about Polish family firms in general? The results of the recent survey (KPMG, January 2015) show that 49% of Polish (compared to 34% of Europeans) respondents emphasized the importance of the philanthropy in their day to day activity. This question definitely requires more research and analysis. However, the theory indicates that CSR approach is more internally oriented i.e., family firms act responsibly focusing on the benefit and interest of the family, at the same time being the key actor in the family business systems and the key stakeholder. The search for the answer to the question of how the specificity of family businesses affects CSR and financial performance paves the way for further research potential opportunities in the future.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Science Centre in Poland, project no. 2012/07/B/HS4/03047 “Governance and control mechanisms in a large family business in Poland”.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Anderson, R. C., and Reeb, D. M. (2003), ‘Founding-Family Ownership and Firm Performance: Evidence from the S & P 500’, LVIII(3), 1301–1328.

- Astrachan, J. H., and Shanker M. C. (2003), ‘Family Businesses’ Contribution to the U. S. Economy: A Closer Look’, Family Business Review 16(3), 211–219.

- Ayranci, E. (2014), ‘A study on the influence of family on family businesses and its relationship to satisfaction with financial performance’, Business Administration and Management, 17(2), 87–105.

- Bakanauskiene, I., Staniuliene, S., Zirgutis, V. (2016), ‘Corporate social responsibility: the context of stakeholders pressure in Lithuania’, Polish Journal of Management Studies; 13 (1): 18-29.

- Beckhard,, and Dyer, W. G. (1983), ‘Managing Change in the Family Firm-Issues and Strategies’, Sloan Management Review, 22, 3, 59-65.

- Berrone P., Cruz C.C., and Gómez-Mejía L.R. (2012), ‘Socioemotional wealth in family firms: A review and agenda for future research’, Family Business Review, 25(3), 258–279.

- Bowen, H.P. (1953),’ Social Responsibilities of the Businessman’, Harper, New York.

- Carney, M. (2005), ‘Corporate Governance and Competitive Advantage in Family- Controlled Firms’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 249–265.

- Chrisman, J., Chua, J., and Sharma, P. (2005), ‘Trends and Directions in the Development of a Strategic Management Theory of the Family Firm’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 555–575.

- Chrisman, J. J., and Chua, J. H. (2005), ‘Sources and Consequences of Distinctive Familiness: An Introduction’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 5, 237–247.

- Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., and Sharma, P. (1999), ‘Defining the Family Business by Behavior’, Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 23, 19–39.

- Churchill, C, and Hatten, K. J., ‘Non-Market-Based Transfers of Wealth and Power: A Research Framework for Family Businesses’, American Journal of Small Business,1987, 11(3), 51-64.

- Claessens, , Djankov S., and Lang L.H.P., 2000, ‘The Separation of Ownership and Control in East Asian Corporations’, Journal of Financial Economics, 8 (2000) 81-112.

- Davis, P. S., and Harveston, P. D. (1998), ‘The Influence of Family on the Family Business Succession Process: A Multi-Generational Perspective’, Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 22, 31–54.

- Elbaz J., Laguir I. (2014), ‘Family Businesses And Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Orientation: A Study of Moroccan Family Firms’, Journal of Applied Business Research, 30(3), 671–68.

- European Commission, 2009, ‘Final report of the expert group overview of family-business- relevant issues: Research, network, policy measures and existing studies. [online] Available at: [Accessed 15 February 2015].

- Giovannini R. J. (2010), ‘Corporate governance, family ownership and performance’, Journal of Management and Governance, 14, 145–166.

- Graafland J., Eijffinger S.C.W., Stoffele N.C.G.M., Smid H., and Coldeweijer A.M. (2003),’ Corporate Social Responsibility of Dutch Companies: Benchmarking and Transparency’, CMO Report, Tilburg University, http://www.uvt.nl/wijsbegeerte/cm

- Handler, W. C. (1989), ‘Methodological Issues and Considerations in Studying Family Businesses’, Family Business Review, 2 (3), 257-276.

- Karra, N., Tracey, P., and Phillips, N. (2006), ‘Altruism and Agency in the Family Firm’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 861–878.

- Klein, S. B. (2000), ‘ Family Businesses in Germany: Significance and Structure’, Family Business Review, 13(3), 157–181.

- Klimek J. (2014), ‘W rodzinnej firmie. Powstanie, rozwój, zagrożenia i szanse’, Wydawnictw Menedżerskie PTM, Warszawa.

- La Porta, R., Lopez de Silanes F., and Shleifer A. (1999), ‘Corporate ownership around the world’, Journal of Finance 54, 471-517.

- Leszczewska K. (2016), ‘Przedsiębirostwo rodzinne. Specyfika modeli biznesu’, Difin, Warszawa.

- Litz, R. A. (1995), ‘The Family Business: Toward Definitional Clarity’, Family Business Review 8(2), 71–81.

- López-Cózar, C., and Hilliard, I. (2014), ‘Family and Non-Family Business Differences in Corporate Social Responsibility Approaches’, ASEAN Journal of Management and Innovation (December), 74–85.

- López-Cózar C., Priede T., and Hilliard I. (2014), ‘Are family firms really more socially responsible?’, Asean Journal of Management & Innovation, June-December, 74–85.

- Madison, K., Holt, D. T., Kellermanns, F. W., and Ranft, A. L. (2016), ‘Viewing Family Firm Behavior and Governance Through the Lens of Agency and Stewardship Theories’, Family Business Review, 29(1), 65–93.

- Madorran C., and Garcia T. (2016), ‘Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: the Spanish case’, Revista de Administração de Empresas, 56(1), 20–28.

- Martyniuk O., and Majerowska E. (2017), ‘Corporate Social Responsibility of Polish Family Firms – Results of Empirical Studies’, Przedsiębiorczosć i Zarzązdanie, XVIII, (6), 323–334.

- Masuo, D., and Tamayose, J. (2014), ‘Corporate Social Responsibility of Family Businesses in Hawai‘i’, Family Businesses. International Conference on Business and Social Sciences, March 29-31, 2016, Kyoto, Japan.

- Pearson, W., Carr, J.C. and Shaw, J.C., ‘Toward a Theory of Familiness: A Social Capital Perspective’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 32, Issue 6, 949-969.

- Perrini, F., and Minoja, M. (2008), ‘Strategizing corporate social responsibility: evidence from an Italian medium-sized, family-owned company’, Business Ethics: A European Review, 17(1), 47–63.

- Popowska, M. (2015), ‘CSR in family business – ethnocentric meaning socially responsible’, Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie, XVI(7), 119–132.

- Popowska M. (2017), ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and Family Business: Current Debates and Future Prospects’, Przedsiębiorczosć i Zarzązdanie, XVIII (6), 281–292.

- Russo, A and Perrini, F. (2009), ‘Investigating stakeholder theory and social capital: CSR in large firms and SMEs’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 91, no. 2, 207-221.

- Sacristán-Navarro, M., Gómez-Ansón, S., and Cabeza-García, L. (2011), ‘Large shareholders’ combinations in family firms: Prevalence and performance effects’, Journal of Family Business Strategy, 2(2), 101-112.

- Tagiuri R. and Davis J. (1996), ‘Bivalent Attributes of the Family Firm’, Family Business Review, Vol. 9, No. 2, 199-208.

- Znaczenie Firm Rodzinnych dla polskiej gospodarki (201), PARP, Warszawa, http://firmyrodzinne.pl/download/pentor/Raport_koncowy_Badanie_firm_rodzinnych.pdf

- Zulkifli, N., Hasan, H. bu, Saleh, Z., and Zainal, D. (2011), ‘Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR) In Malaysian Family Business’, 3rd International Conference on Governance, Fraud, Ethics and Social Responsibility, 1–13