Introduction

According to Ibañez (1988), the most relevant aspect in the definition of conflict is that it should stem from the social players’ subjectivity, and more specifically from their cognitive representations, so as to differentiate it from other similar states of discord such as an objective counter-position or competition. Several conflict literaturere views show little consensus when it comes to accepting a generic definition of conflict. Cunha et al. (2016), Lewicki, Weiss and Lewin (1992), Kolb and Putnam (1992) point out that perspectives, as well as difficulties in defining conflict, abound – and, in general, no definition prevails over the others. According to Serrano and Rodriguez (1993), despite conflict being analyzed from several points of view, which correspond to different analytical perspectives and different phenomenon explanation levels, these are not, on principle, contradictory. Different scholars converge, arguing that conflict is an interactive process and may occur whenever two or more social entities (individuals, groups, organizations, nations) interact and their interests or goals are perceived as incompatible or dissonant. (Deutsh, 1994; Pruitt et al., 1994; Smith, 1966, Thomas, 1976; Ting-Toomey, Oetzel and Yee-Jung, 2001). Others add that the relationship between entities might become incompatible or inconsistent either when two or more entities seek the same goods or resources, and these are scarce, arousing feelings of exclusivity towards said goods or resources between these entities, or when they have different attitudes, values, beliefs or abilities (Antonioni, 1998; Bercovitch, 1984; Cunha, 2001; Rahim, 2001 and 2002; Einarsen et al., 2018; Van de Vliert, 1985).

Cunha (2001) draws attention to the fact that to speak with authority in conflict, the parties in the litigation must understand the incompatibility of their goals, and that there are interdependent ties- either functional, structural or merely historical – that prevent each party from achieving their goals without counteracting the other. On the other hand, Serrano and Rodriguez (1993) caution that there is subjectivity in terms of connotations of definitions centered on the incompatibility of the parties. They mention that partial or total incompatibility of goals does not imply they really are so. Regardless of what happens, incompatibility often stems from a distorted perception that accentuates the most diverging elements and not the common interests. Therefore, according to the author, the analysis of this dimension requires not only a motivational perspective, but also a perceptive one, given that any conflict carries with itself a particular background of stereotypes, prejudices, ethnocentric visions and biased perceptions of the opponent that curtail the supposed inability to reach an agreement.

Interpersonal Conflict In Organizations

Interpersonal conflict is a fundamental component of the organizational experience, in which one’s individual goals, desires and expectations suffer interferences from others, creating diverging interests or the belief that each player’s aspirations cannot be achieved simultaneously (Lee, 2002; Moberg, 2001; O´Connor et al., 2002; Ohbuchi and Fukushima, 1997; Pruitt et al., 1994). In a more enlightening manner, Rahim (1992 and 2001) mentions that interpersonal conflict in organizations refers to manifestations of incompatibility or to disagreement between two or more people at the same or at a different hierarchical level, in a situation where one or more persons’ goals are mutually exclusive, creating hostile attitudes.

The subjectivity of the emergence of conflict very often arises from the fact that many people do not like engaging in conflict because of its negative consequences. The natural reaction is to avoid or end conflicts as soon as possible. The negative associations that exist towards conflict influence, without a doubt, how we face and respond to it (Jehn, Northcraft and Neale,1999). If conflict becomes intense, social players will stray from a convenient and sensible relationship and focus their efforts towards victory. Once the immediate objective of each of the parties is to win or have control over the situation, the interest in solving the problem(s) becomes less and less important. Therefore, the players are less predisposed to contribute to effective organizational goals (Rahim, 2002). According to Bergmann and Volkema (1994), interpersonal conflict between co-workers has the potential to divide a team and proliferate throughout the company. However, avoiding or suppressing conflict is often a mistake, and does not always meet the real interests of those involved. In that regard, Tjosvold (1997) argues that interpersonal conflict may develop each person’s individuality, so as to feel satisfied and able, given that it provides an opportunity to express one’s needs, opinions and stances. At the same time, there is an attempt to understand the other party’s positions, which contributes to diminishing an egocentric attitude.

Given the aforementioned assumption –that conflicts are a consequence of one’s own social interaction –, the idea that the goal should consist in displaying adequate skills and tools to face them with a positive demeanor, should be reinforced. Beitler, Scherer and Zapf (2018); Deutsh (1994); Munduate et al. (1993), Pruitt et al. (1994) and Serrano & Rodriguez (1993) argue that the effects of conflict are positive when we know how to handle them properly, in a way that establishes relationships that are increasingly cooperative. This once again seems to reinforce the vision of Rahim (2000) regarding increased organizational learning, so as to boost people’s efficiency in handling conflicts in a sustained manner.

Interpersonal Conflict Handling

According to Van de Vliert (1985), conflict handling is what those involved intend to do, as well as what they really do. It encompasses changes in attitude, behavior and in the organizational structure that allow members of the same organization to work with each other effectively, achieving their individual and/or group goals (Scherer and Zapf, 2018; Rahim, 1992; 2001; Yoko, Hartel and Callon, 2002). Despite the growing awareness that conflict in organizations can be functional, many of the recommendations continue to fall on the spectrum of mitigation, resolution or minimization, which is to say, they promote conflict resolution and not conflict management. The difference between the two concepts is not just semantics (Robbins, 1978). What contemporary organizations need is conflict management and not conflict resolution. Conflict management does not necessarily imply avoiding, decreasing or ending conflicts altogether, it involves effectively outlining strategies to minimize dysfunctions and fostering constructive roles so as to increase organizational learning and efficiency (Rahim, 2001 and 2002; Kessler et al., 2013).

Organizational learning is of the essence, and many contemporary academics state that it is not a matter of wanting or not wanting to learn, but rather that organizations need to learn as soon as possible. Tension and conflict seem to be essential characteristics of learning organizations, in which tension and conflict are underlined by questioning, unbalancing and challenging the status quo (Garvin, 1993, Schein, 1993, Senge, 1990). Argyris (1994) suggests that existing theories reveal processes of anti-learning, which can be better described as quasi– conflict resolution models. Several scholars mention the need to handle conflicts in a constructive way, to realize the collective learning potential. Thus, corroborating Rahim (2001 and 2002), the need to strengthen and consolidate conflict handling at the highest organizational levels is implied to encourage organizational learning and efficiency. Amason (1996), Jehn, Northcraft and Neale (1999), among others, suggest that conflict handling involves the acknowledgement of the following principles in regard to the performance of individuals and groups: certain specific types of conflicts may cause negative effects and should be diluted. These conflicts are generally caused by the actions and negative reactions of members of the organization, for example personal attacks, racial disharmony and sexual harassment; yet there are other types of conflicts that may have positive aspects, and such is the case of disagreements that spurred from tasks, action plans and other organizational issues. The members of the organization, in their interactions with one another, will have to deal with their disagreements in a constructive manner, which leads to serious learning about how to use conflict handling styles to face different situations in an effective way.

According to Tjosvold (1997), well-managed conflicts are an investment for the future. People believe in one another, feel more powerful, effective and more prepared to contribute to their groups and organizations. In fact, in an organizational environment, individuals that handle conflicts effectively are seen as competent speakers and as having leadership skills (Gross & Guerrero, 2000; Luthans, Rosenkrantz and Hennessey, 1985). In line with Blake & Mouton (1978) and Thomas (1976), Rahim and Bonoma (1979) and Rahim (1983a) differentiate interpersonal conflict handling styles through two basic dimensions: personal interest, which explains the degree (high or low) to which a given subject seeks to satisfy their own interest, and the other’s interests. These dimensions are subject to different combinations, resulting in five specific styles, designated as follows (Rahim 1983a, 1986, 2000, 2001 and 2002; Rahim and Bonoma, 1979):

- Integrating, which is characterized by a high interest, both in one’s own results and the other party’s. This style implies collaboration between both parties, exchange of information and an active search for an acceptable solution that works for both. Therefore, a direct communication between the parties is established, boosting the occurrence of creative solutions for both;

- Obliging, which is characterized by low investment in oneself, but high investment in the other party. This style implies the satisfaction of the other party’s interests over one’s own interests. When one of the parties adopts this style, they opt not to consider their differences towards the other and weigh in shared aspects, seeking to satisfy the other party’s interests;

- Dominating, which is characterized by high investment in oneself and low investment in the other party. In this style, one tries to achieve their own goals without caring for the other’s interests;

- Avoiding, characterized by low investment in one’s own results and in the other party’s;

- Compromising, this style positions itself in the middle of the aforementioned four styles, characterized by an intermediate interest for oneself and other parties.

Empirical Study

The overall objective of this research is to describe the conduct of individuals in situations of interpersonal conflict in an organizational context among co-workers, and check how conflict handling styles are determined by the variables sex and level of education. The specific goals that the author sets are the following: identify profiles of interpersonal conflict handling between peers in each of the subjects; assess to what extent interpersonal conflict handling styles are determined by certain demographic characteristics.

Using the theoretical studies as a reference, the following hypothesis are proposed:

H1 – The integrating and compromising styles are the most used in interpersonal conflict situations between peers–co-workers. On the contrary, avoiding, obliging and dominating styles are less frequently used.

H2 – In interpersonal conflict situations between peers – co-workers, the dominating style is more predominant in male subjects than in women.

H3 – In interpersonal conflict situations between peers – co-workers, the avoiding and obliging styles are more predominant in females than in men.

H4 – In interpersonal conflict situations between peers – co-workers, subjects with a higher level of education integrate more and use avoiding less than those with a lower level of education.

Sample And Methodology

In this study, independent demographic variables and one dependent variable were considered for interpersonal conflict handling styles between peers in an organizational context.

Independent variables: Sex – the sample includes male and female subjects. Level of education – this variable is composed of three levels, Basic Education (up to 9th grade), Secondary Education (up to 12th grade/K-12) and Higher Education (University degree). Years of professional experience – divided into five groups – up to 5 years; 6 to 15 years; 16 to 25 years; 26 to 35 years and over 36 years of professional experience.

Dependent variable: conflict handling styles. In this category, the five interpersonal conflict handling styles between peers – co-workers in an organizational context: integrating, compromising, obliging, dominating and avoiding, using the approach suggested by Rahim and Bonoma (1979) and Rahim (1983a).

Measurement tool: To assess interpersonal conflict handling styles, the “ROCI-II, Rahim Organizational Conflict Inventory” (Rahim,1983b) was used. This inventory has its theoretical basis in the two-dimensional approach of five factors by Rahim & Bonoma (1979) and Rahim (1983a). Thus, conflict management is considered on the basis of a two-dimensional model. On the one hand, there is the importance attributed to one’s own interests and, on the other hand, the importance attached to the interests of the other party. This defines the five conflict handling styles: integrating, obliging, dominating, avoiding and compromise (Rahim, 1983a, 1983b). The tool consists of 28 questions and comprises A, B, C forms, through which, the author intended to measure how individuals handle interpersonal conflict situations with their superiors (A), their subordinates (B) and their peers (C). In this study, the C form is applied referring to peer conflict – co-workers, comprised of 28 questions which are answered through a Likert scale with five potential replies, in which 1 corresponds to Strongly Disagree and 5 to Strongly Agree, and in which higher values represent greater use of a style and vice-versa. (Rahim, 1983c, 2001). ROCI-II also requests information regarding sex, level of education and profession.

With the translation and adaptation of the questionnaire’s C form in mind, the original version of the questionnaire by Rahim (1983b) was used after being translated to portuguese. So as to test the interpretation and comprehension of each question, the questionnaire was trialed on 20 workers from the public organization where the sample for this study was collected later on. It was then revised, consulting the original questionnaire also translated to Portuguese in the study by Cunha, Moreira & Silva (2003) with a national sample of 197 subjects, and it was submitted to a new trial with 41 workers. With data analysis and its respective conclusions in mind, several quantitative analysis were made using the SPSS – Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 16.0.

The study used a sample of 181 subjects, workers from several hierarchical levels and departments from a Portuguese public organization. There were 113 female subjects, which represent 62% of the total and 68 male subjects, who represent 38%. About half (49%) of the subjects have a university degree, followed by secondary education (36%9) and finally by subjects with only basic education, who represent 15%.

Analysis And Interpretation Of The Results

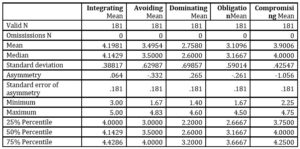

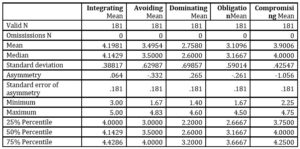

Regarding the C form questionnaires of the “ROCI-II” inventory, the author calculated an average value for each questionnaire and for each one of the five conflict handling styles, whose minimum value could be 1 and the maximum could be 5, which means 3 is the average value. From table 1, it can be ascertained that the predominant style is integrating, followed by compromise. Avoiding appears in the third position, followed by obliging, which is displayed in above-average values. The least adopted style is domination. The response scattering is more accentuated in the dominating style, followed by avoiding and obliging. There is less scattering in the integrating and compromising styles.

Table 1: Statistical data observed in the responses related to the five Styles of conflict management

Source: Own elaboration based on SPSS output

Source: Own elaboration based on SPSS output

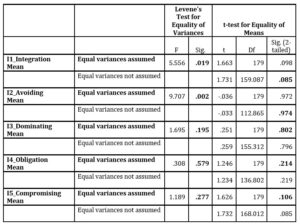

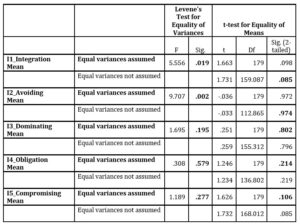

Therefore, taking into consideration the results, hypothesis #1 is confirmed, which mentioned a greater predominance of the integrating and compromising styles and that obliging, avoiding and dominating are less frequent. So as to verify the significance level of the differences between the values surveyed for both sexes, the t-test was used, preceded by the hypothesis test to the equality of variances. Table 2 presents .019 test values for integrating and .002 for avoiding, therefore, less than 5%. Dominating registers .195, obliging .579 and compromising .277, with significance values above 5%. Therefore, dominating, obliging and compromising have the same variance, but integrating and avoiding do not.

Table 2: Significance of gender differences in conflict management style, preceded by hypothesis testing to the equality of variances

Source: Own elaboration based on SPSS output

Source: Own elaboration based on SPSS output

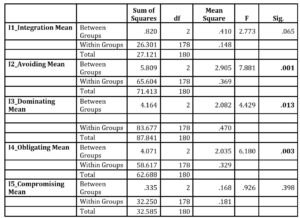

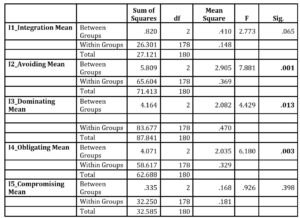

Taking into consideration these values for the t-test, the author verifies that test values are always above 5%, so they never allow us to reject the null hypothesis, which would be having the same variables for both sexes in integrating, avoiding, dominating, obliging and compromising or, in other words, that there are no differences between both sexes in what concerns conflict handling styles. This leads us to conclude that the subjects of this study, whether they are men or women, share a very similar position regarding conflict handling. Thus, hypothesis #2 is denied, which mentioned a greater prevalence of dominance in males, as well as hypothesis #3, that pointed towards a greater predominance of avoiding and obliging amongst the female sex. The analysis of variance – ANOVA (Table 3) allows us to see that for avoiding (.001), dominating (0.013) and obliging (.003), the hypothesis that the averages are the same across different levels of education is denied.

Table 3: ANOVA – Hypothesis testing for equality of Variances for educational qualifications

Source: Own elaboration based on SPSS output

Hypothesis #4 is partially confirmed, when the author points towards subjects with higher levels of education as less avoidant. Not confirming that the subjects with higher educational qualifications would be more integrators. There are no significant differences, which support this hypothesis.

Conclusions And Guidelines For Management

Through this study, it can be concluded that men and women share very similar positions towards conflict handling, concurring with the results of studies conducted by Cunha, Moreira & Silva (2003), Munduate, Ganaza, and Alcaide (1993), Shockley-Zalabak, (1981) Sorenson, Hawkins and Sorenson (1995). The relation between gender differences and interpersonal conflict handling styles has been the subject of several studies, and the authors that encountered significant differences do not present unanimous tendencies. For example, Rahim (1986) obtained results that suggest that women use avoiding, integration and compromise more and obliging less than men; whilst studies by Brewer, Mitchell and Weber (2002) suggest that women use avoiding more and men use dominance more; studies by Baxter and Shepard (1978), Hill, Henry and Green (1997) found evidence that suggests women prefer non-confrontational styles, while men prefer competition and controlling styles.

The registered predominance of the integrating and compromising styles and the lower frequency of avoiding, obliging and dominating styles in conflict situations between peers seem to concur with studies by Munduate Ganaza and Alcaide (1993), Lee (2002) and Rahim (1986), amongst others. As Lewicki, Weiss and Lewin (1992) mention, responses to conflict are a result of the subject’s direct learning and relearning through behaviors and previous experiences, clearly influenced by individual perception and comprehension of the organizational context. This may lead those who are less experienced to adopt conflict handling styles in a less premeditated manner, according to the circumstances and the way they perceive them, probably due to greater irreverence, competitiveness and, mostly, less knowledge about all the implications it may have in an organizational context.

More than a succession of categorical conclusions, this article aims to draw attention to the social relevance of this issue. Being an exploratory research as well, it will restrict the extrapolation of the results to different organization realities. It seems pertinent, however, to make some management recommendations that could be extended to other organizational contexts. The first recommendation of this study refers to the acceptance, by organizations, that conflicts are a consequence of social interaction itself, and that, beyond legitimate, they are inevitable, and therefore must be handled and not resolved (or mitigated). As Robbins (1978) refers, the difference between the two concepts is much greater than semantics. The challenge will be incorporating and promoting human resources management procedures and guidelines that reflect that reality. Creating tools and skills that allow handling interpersonal conflict properly, which according to Rahim (2001), should be achieved through the increase of organizational learning, so as to increase people’s efficiency in conflict handling in a sustained fashion. Organizational learning is of the essence, and many contemporary academics state that for organizations, it is no longer a matter of wanting to learn, but rather learning as fast as possible – given the importance of organizational conflict and the complexity associated with its management, it is essential that workers across all hierarchical levels understand the contexts in which organizational conflicts occur, and know a variety of techniques to handle them. Corroborating Garvin (1993) and Rahim (2002), organizational learning, in what concerns conflict management, requires company cultures that support experimentation, risk-taking, openness to new points of view and a continuous attitude that questions and inspires sharing information and knowledge.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Amason, A. C. (1996). Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making: Resolving a paradox for top management teams. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (1), 123-148.

- Antonioni, D. (1998). Relationship between the big five personality factors and conflict management styles. The International Journal f Conflict Management, 9 (4): 336-355.

- Argyris, C. (1994). Good communication that blocks learning. Harvard Business Review, 72 (5), 77-85.

- Baxter L.A. and Shepard, T.L.(1978). Sex role identity, sex of other, and affective relationship as determinants of interpersonal conflict – management styles. Sex Roles, 4 (6), 813-825.

- Beitler, L.A., Scherer, S. and Zapf, D. (2018). Interpersonal conflict at work: Age and emotional competence differences in conflict management. Organizational Psychology Review, 8(4), 195-227.

- Bercovitch, J. (1984). Problems and approches in study of bargaining and negotiation. Political Science, 36 (2), 125-145.

- Bergmann T. J. andVolkema, R. J. (1994). Issues, behavioral responses and consequences in interpersonal conflicts. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(5), 467-471.

- Blake, R. R. and Mouton, J. S. (1978). The new managerial grid. Houston: Gulf Publishing.

- Brewer, N., Mitchell, P. and Weber, N. (2002). Gender role, organizational status, and conflict management styles. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 13 (1), 78-94.

- Cunha M.P., Rego A., Cunha R.C. and Cabral-Cardoso, C. (2016). Manual de comportamento organizacional e gestão (pp.436-459). Lisboa: Editora RH.

- Cunha, P. (2001). Conflito e negociação. (pp.23-47) Porto: Edições Asa.

- Cunha, P., Moreira, M. and Silva, P.I. (2003). Estilos de gestão de conflito nas organizações: uma contribuição para a prática construtiva da resolução de conflitos. Recursos Humanos Magazine, 29, 42-52.

- Deutsch, M. (1994). Constructive conflict resolution: principles, training, and research. Journal of Social Issues, 50 (1), 13-32.

- Einarsen, S., Skogstad, A. Rorvik, E. Lande, A. and Nielsen, N.B. (2018). Climate for conflict management, exposure to workplace bullying and work engagement: a moderatedmediationanalysis. TheInternationalJournalofHumanResource Management, 29 (3), 549-570.

- Garvin, D.A. (1993). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 71 (4), 78-92.

- Gross, M. and Guerrero, L. (2000). Managing conflict appropriately and effectively: An application of the competence model to Rahim´s organizational conflict styles. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 11 (3), 200-226.

- Hill, K.L., Henry, W. A. and Green J.S. (1997). Gender Norms may determine conflict management style in the organizational environment. Proceedings of the Academy of Managerial Communication, 2 (2), 20-26.

- Ibañez T. (1988). El conflito social. Perspectivas clássicas y enfoque renovador. In Boletín de Psicología, 18 (1), 342-365.

- Jehn, K.A., Northcraft, G. and Neale, M. (1999). Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict and performance in workgroups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44 (4), 741-763.

- Kessler, S.R., Bruursema, K., Rodopman, B. andSpector, P.E. (2013). Leadership, interpersonal conflict, andcounterproductiveworkbehavior: Anexaminationofthestressor–strainprocess. Negotiationand Conflict Management Research, 6 (3), 180-190.

- Kolb, D.M. and Putnam, L. (1992). The multiple faces of conflict in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13 (3), 311-324.

- Lee, C.-W. (2002). Referent role and styles of handling interpersonal conflict: Evidence from a national sample of korean local government employees. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 13 (2), 127-141.

- Lewicki, R.J., Weiss, S.E. and Lewin, D. (1992). Models of conflict, negotiation and third part intervention: a review and synthesis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13 (3), 209 – 252.

- Luthans, F., Rosenkrantz, S. and Hennessey, H. (1985). What do successful managers really do? An observation study of managerial activities. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 21 (3), 255-271.

- Moberg, P.J. (2001). Linking conflict strategy to the five-factor model: Theoretical and empirical foundations. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 12 (1), 47-68.

- Munduate, L. Ganaza, J. and Alcaide, M. (1993). Estilos de gestión del conflicto interpersonal en las organizaciones. Revista de Psicología Social, 8 (1), 47-68.

- Ohbuchi, K.-I. and Fukushima, O. (1997). Personality and interpersonal conflict: Agressiveness, self-monitoring, and situational variables. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 8 (2), 99-113.

- O´Connor, K.M., De Dreu, K.W., Schroth, H., Barry, B., Lituchy, T.R. and Bazerman, M.H. (2002). What we want to do versus what we think we should do: an empirical investigation of intrapersonal conflict. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15 (5), 403-418.

- Pruitt, D.G, Rubin, J.Z. and Kim, S.H. (1994). Social conflict: Escalation, stalemate and settlement (2nd) New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Rahim, M.A. (1983a). A measure of styles of handling interpersonal conflict. Academy of Management Journal, 26 (2), 368-376.

- Rahim, M.A. (1983b). Rahim organizational inventories – II, forms A, B & C. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Rahim, M.A. (1986). Referent role and styles of handling interpersonal conflict. The Journal of Social Psychology, 126 (1), 79-86.

- Rahim, M.A. (2001). Managing Conflict in Organizations (3ª Ed.), Westport: Quorum Books.

- Rahim, M.A. (2002). Toward a theory of managing organizational conflict. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 13 (3), 206-235.

- Rahim, M.A. andBonoma, T. V. (1979). Managing organizational conflict: a model for diagnosis and intervention. Psychological Reports, 44,1323-1344.

- Robbins, S.P. (1978). Conflict management and conflict resolution are not synonymous terms. California Management Review, 21 (2), 67-75.

- Senge, P.M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of learning organization. New York: Doubleday.

- Schein, E.H. (1993). How can organizations learn faster? the challenge of entering the green room. Sloan Management Review, 35 (2), 85-92.

- Serrano, G. andRodriguez D. (1993). Negociacíon en las organizaciones. Madrid: Eudema.

- Shockley – Zalabak, P. (1981). The effects of sex differences on the preference for utilization of conflict styles of managers in a work setting: An exploratory study. Public Personnel Management, 10, 285-295.

- Smith, C.G. (1966). A comparative analysis of some conditions and consequences of interorganizational conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 10 (3), 504-529.

- Sorenson, P.S., Hawkins, K. andSorenson, R.L. (1995). Gender, psychological type and conflict style preference. Management Communication Quarterly, 9 (1), 115-126.

- Thomas, K.W. (1976). Conflict and conflict management. In M.D. Dunete (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp.889-935). Chicago: Rand-McNally.

- Ting-Toomey, S., Oetzel, J.G. and Yee-Jung, K. (2001). Self-construal types and conflict management styles. Communication Reports, 14 (2), 87-95.

- Tjosvold, D. (1997). Conflict within interdependence: its value for productivity and individuality. In C. De Dreu & Van de Vliert (Eds.). Using conflict in organizations. London: Sage Publications.

- Van de Vliert, E. (1985). Conflict-prevention and escalation. In D.J. Drenth, H. Thierry, P.J. Willens & C.J. Wolf (Eds.), Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 1 (pp. 521-551), New York: Wiley.