Introduction

Due to constantly changing environment contemporary organisations need to redefine the roles of their managers and highlight the significance of certain competences. They are primarily required to attract, maintain and develop the most competent people, keep high efficiency, stimulate innovation, adjust mutual visions, strategies and conduct and provide a work-life balance. Still, they cannot forget about other important issues, such as: swift operation in a multicultural environment, preparedness for lifelong learning, high standards of conduct, creativity and flexibility as well as aptitude to take risks (Connaughton & Shuffler, 2007; Costa et al., 2017; Samul et al., 2021).

A traditional team consisting of members of the same origin largely exhibits predictable dynamics. Here, heads primarily concentrate on different types of personalities and temperaments of their subordinates, as well as react to the following challenges: errors and mistakes, extra work, conflicts, or handling non-standard situations. However, being a member of a multicultural team requires extensive knowledge of cultural behavior since an environment that brings together representatives of different nationalities is in many ways different from a mono-cultural team. What differs is the type and scale of problems, and so are the ways to prove effectiveness in solving them. This gives priority to the value system, nature and type of defined goals and their communication. On this, background there emerges a significant role of a leader (Gadomska-Lila et al., 2011, Samul et al., 2020).

The authors of this article aim to diagnose different perceptions of leadership in multicultural teams, as provided by survey participants from Poland and Romania.

Leadership In Multicultural Teams – Theoretical Background

Leadership is a process by which a person influences others to accomplish an objective and directs the organization in a way that makes it more cohesive and coherent. It is a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal (Sharma & Jain, 2013; Burakova & Filbien, 2020). In management science leadership is one of the most often explored research subject which is confirmed, for example, by the number of attempts to define this phenomenon (over 128,000,000 internet results) (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007; Eklund et al., 2017; Harrison, 2018).

Interest in the topic of leadership in an organization is constantly growing, as well as the search for the conditions of successful leadership. Based on this search for the conditions of successful leadership, many leadership theories have emerged: the Great Man theory with an attempt to answer the question “who a leader is”; behavioral theory with “what a leader does”; contingency theory with “where does leadership happen or occur”; and transactional leadership, transformational leadership, and other types of leadership with “what does a leader think about, mind, and do” (Aritz & Walker, 2014; Samul, 2019). The reason for these theories and concepts is to search for the most effective leadership style.

In all, probability the popularity of this issue is the result of numerous reasons but its multiplicity and complexity seem to be extremely important since leadership concerns the person of the leader – his personality traits as well as his relational skills. Leadership as a research concept continually enters new areas of management science including that of management culture or relational management. The scientific popularity of leadership most likely is utilitarian in nature since a leader not only directly impacts the enterprise and decides about its success as an organization but also influences its market success (Szydło & Widelska, 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Szydło et al., 2020; Samul et al., 2020). The responsibility of a leader is therefore undeniable and the systematic progress of scientific exploration in regard to seeking sources of various determinants of the impact a leader has on people and the organization as a system is not surprising since the immense and direct responsibility for the development of numerous spheres of the organization for which he is liable falls onto his shoulders. In referring to the current, very abundant scientific achievement in the area of leadership the most exhibited and still expanded issues, oscillating mainly around theories of leaders and styles of management, must be addressed. In dealing with the theory of leadership we must focus on the domain of personality where the sources of the leader’s predestination to his role within the organization are his inborn and/or acquired abilities (see among others Gibb, 1954; Katrz & Khan, 1978; Yukl, 1989; Koźmiński & Piotrowski, 2000; Kuc, 2006; Van Velsor et al., 2010; DeRue et.al., 2011; Charry, 2012; Eva et al., 2019). The achievement of the personality theory of leadership allows the assessment of the leader through the prism of his traits which include, among others: intelligence, self-motivation, relatively high desire to achieve, being oriented at the well-being of his subordinates, the ability to solve problems and identify tasks or professional and technical skills. The ability to manage multicultural teams is also an important challenge (Kraft, 2018; Puni et al., 2018; Van Saane, 2019, Gerpott et al., 2019; Szydło et al., 2020). This aspect is central to the debate on leadership research topics.

Apart from performing standard leadership activities that include planning, organizations, controlling, and motivation boosting, leaders of multicultural teams must possess a certain set of attributes in that respect. These are: being tolerant, respectful, empathetic, open to change and goal-oriented (Kożusznik, 2005). Also, leaders need to know the merits and needs of their subordinates, attempt to create a cooperative atmosphere as well as target culturally conditioned issues and overcome their own cultural stereotypes. Other important skills include: promoting collaboration with a view to mutual respect and fostering communication allowing for requesting and offering feedback, as well as boosting knowledge about cultural gaps (Higgs, 1996; Tang & Wang; 2017). Moreover, a leader must possess impeccable language skills and show curiosity about other cultures that have become someone’s motivator to live in a different country (Matveev, 2017). Such qualities are considerably associated with cultural intelligence. Cultural intelligence grows together with multinational experience, but even without that it can be mastered through training. Cultural intelligence is one’s ability to interpret signals that come from a culturally different setting in an adequate manner (Earley & Ang, 2003; Ang & Van Dyne, 2008; Edmondson, 2012; Edmonson & Harvey 2018). To make it possible, such a leader should exhibit a good deal of cognitive abilities. A high level of cultural intelligence allows handling communication intricacies, where the party to the interaction feels included and respected. Hence, it is possible to establish mutual trust (Burakova & Filbien, 2020). A culturally intelligent person better understands representatives of other cultures and may conduct a meaningful dialogue with a view to attaining intended objectives (Piotrowski & Świątkowski, 2000; Rockstuhl et al., 2011; Boyraz, 2019).

Research Methodology

The study was conducted using the method of the diagnostic survey with the CAWI (Computer-Assisted Web Interview) technique. The time frame spanned over the period between January and April 2019, and the location covered two countries: Poland and Romania. A total of 2,100 correctly completed surveys by students were obtained: 1,121 from Bialystok University of Technology in Poland (53.4% of all respondents) and 979 from the Babes-Bolyai University in the Romania (46.6%) and 119 completed surveys by teachers (62 from Poland and 57 from Romania). At the first stage, a questionnaire was addressed to students, at the second – to academic teachers. The study adopted a questionnaire administered online in order to reach the largest possible group of respondents. The results obtained in this way allow us to know the opinion of a given group of respondents on the research topic and to use them to form certain generalizations. An invitation email containing a link to an online survey was sent to all classes from the bachelor and the master programs of all specializations and academic teachers.

The following research problems were formulated:

- What characteristics should distinguish a multicultural team leader?

- What differences exist in the perception of the role of leader of multicultural teams by respondents from Poland and Romania?

The survey questionnaire prepared in the native languages of participating students was the tool used to carry out the study. The obtained data were subject to statistical analysis using Statistica 13.3 software. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used in the statistical analysis.

Research Results

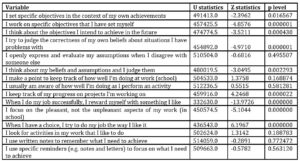

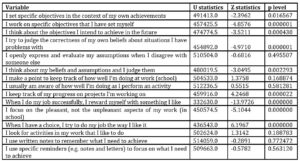

Students were asked to what extent they agree with statements on leadership. They assessed fifteen statements. Table 1 presents statistically significant differences and Table 1– percentage breakdown.

Table 1: Statistically significant differences in leadership qualities

Source: based on (Szydło et al., 2020).

With regard to nine statements, statistically significant differences were found. These included: setting objectives with regard to one’s achievements, working on their development, analysis and judgement of the correctness of one’s beliefs, monitoring the progress and focusing on rewards related to the achievement of one’s objectives, a positive attitude to work and freedom to perform it. On the other hand, there were no differences in terms of diverging opinions with other team members, prioritizing achievements, awareness of the quality of one’s work, seeking activities that correspond with one’s possibilities and tastes, and notetaking with regard to one’s plans and achievements.

Both Polish and Romanian students attached a significant role to pre-established goals in relation to their achievements. With this, respect a mere 16% of Polish and about 14% of Romanian respondents had no opinion. An identical reaction was brought by the statement about working on achieving a specific objective. Still, Romanian respondents (92%), more than the Polish ones (82%), claimed that they devote quite a lot of time to pondering on the objectives they intend to achieve in the future. Both groups comparatively referred to assessing the correctness of beliefs with regard to problematic issues. The same percentage of Poles and Romanians stated that they openly express and evaluate their own assumptions regardless of what others think or say – 75%; in that aspect 19% of Poles and 22% of Romanians provided an “I don’t know” opinion, and about 6% of Polish respondents and only 2% of Romanian ones disapproved of such conduct. Both groups of respondents were inclined towards reflective thinking and attention to work effectiveness. A somewhat higher percentage of Poles (82%) than Romanians (76%) followed the progress of the tasks in which they were engaged. A converse situation was observed in terms of rewarding oneself for successful execution of a task, as confirmed by 80% of Romanian respondents and slightly more than 50% of interviewees from Poland. Also, students from Romania to a greater extent focused on the positive aspects of their work, where a rough 17% of Poles admitted that they could not do so, and 28% had no opinion in that sense, as compared to 7% of respondents from Romania. Both Polish and Romanian respondents exhibited considerable autonomy in choosing the manner in which a given task is to be performed. No significant discrepancies were either observed in the case of notetaking or using specific reminders towards the performance of tasks that lead to achieving objectives.

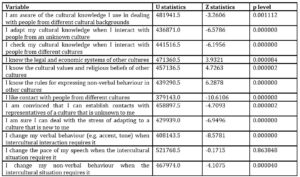

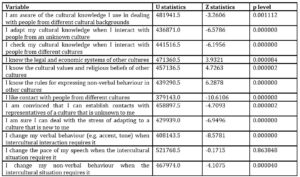

Another question addressed to students concerned cultural knowledge and the ability to apply it (Table 2).

Table 2: Statistically significant differences in knowledge and skills in cooperation

with representatives of other cultures

Source: based on (Szydło et al., 2020).

Here, the respondents had to provide answers to twelve statements. Only with one, i.e., concerning the adaptation of the pace of speech to the benefit of interlocutors, no statistically significant differences were observed, unlike the other eleven statements, where such differences were found. These concerned the awareness of cultural knowledge, the understanding of legal and economic issues, religion, value systems, non-verbal communication, as well as an aptitude for establishing and upkeeping cross-cultural contacts.

The majority of Romanian respondents (70%) agreed that they consciously used their cultural knowledge in dealing with people from foreign backgrounds. An identical answer was provided by 62% of Polish interviewees. Also, most students from Romania admitted adapting their cultural knowledge in interaction with people from other cultures, which was reflected by 79% of positive answers provided by Romanian respondents and a slightly smaller percentage of students from Poland (63%). A similar distribution of positive answers concerned verifying the correctness of cultural knowledge when communicating with people from other cultures. However, a completely different result was obtained in the case of providing answers with regard to the knowledge of legal and economic systems characterizing other cultures. Here, no more than 29% of Polish and 15% of Romanian respondents claimed that they have such knowledge. Almost half of the Romanian and 35% of Polish interviewees could not provide a definite response, and 38% of Romanian and 36% of Polish respondents stated that they have no knowledge of these systems. Still, the knowledge of cultural values and religious beliefs appeared slightly more extensive, as confirmed by 55% of Polish and 39% of Romanian respondents. Here, half of the Romanian respondents could not provide a definite answer. Still the majority of the respondents from both analysed countries stressed that they value and are able to make contacts with foreigners, but are not aware of foreign habits with regard to non-verbal communication. Only 38% of Polish and 20% of Romanian interviewees stated that they do not find anything strange in non-verbal communication used by representatives of different cultures. A small percentage of respondents admitted to stress associated with adapting to a culture different from the native one. The majority of them claimed that they handled it on the whole. A positive answer to that statement was provided by 73% of Romanians and 57% of Poles. An almost identical percentage distribution was observed with regard to statements on adapting verbal and non-verbal communication in cases where an intercultural interaction requires it.

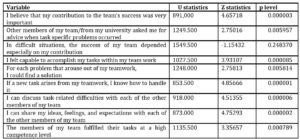

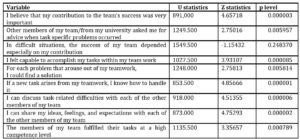

The survey involved not only students, but teachers as well. Their observations concerning predispositions and experiences related to working in multicultural teams are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Statistically significant differences in the experience of academics working in multicultural teams

Source: based on (Szydło et al., 2020).

Academic teachers from Poland and Romania provided different opinions with regard to their experience of working in multicultural teams. No statistically significant differences were observed only in case of one statement, i.e., the one referring to making their decision in difficult situations on which the subsequent success of the team relied.

The research shows that the vast majority of Polish academics, i.e., 76%, as compared to Romanian lecturers (16%), were positive about their significant impact on the success of their team. In the case of respondents from Romania, 60%-70% of them could not provide a definite answer. The majority of Polish interviewees (65%) confirmed that they were asked for assistance in problematic situations. Only 21% of Romanians confirmed that answer. No respondents from either country attributed the success of the entire team to themselves. Furthermore, 94% of interviewees from Poland and 32% from Romania claimed that they generally do well in accomplishing entrusted tasks and, similarly, in finding solutions in new or challenging situations. On the basis of provided answers it can be assumed that the level of collaboration in multicultural teams was more satisfactory in the case of Polish lecturers. Respondents from Poland rated the competence of their team members much higher than Romanian respondents. They also appreciated the level of communication and team-building skills to a much greater extent.

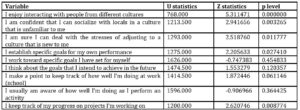

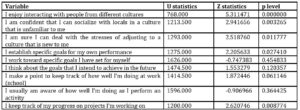

Another issue concerned the assessment of teachers’ predisposition to work in multicultural teams and to act as leaders. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Statistically significant differences in the predisposition of academic teachers

to work in multicultural teams

Source: based on (Szydło et al., 2020).

Here, statistically significant differences were observed for five out of nine statements. These concerned issues associated with such aspects: relationships, adaptation, communication, setting objectives and keeping track of the progress in achievement.

As regards the first statement concerning the sense of having contact with people from other cultures, 87% of Poles and merely 21% of Romanians provided positive answers. The respondents also significantly differed in their evaluation of their ability to relate to others and adapt to the specifics of different cultures. The Polish lecturers gave an affirmative answer, while most Romanian respondents had no opinion. Another finding is that both research groups believe that they rather set themselves objectives they wish to achieve. In the case of statements about goal orientation in the course of performed projects, Romanian lecturers were divided – 47% agreed with it, and almost half of the second group had no opinion. Still, Polish respondents were unanimous in terms of that question – 97% were of positive opinion. Most of the interviewees claimed that they were aware of the quality of performed work. Lastly, the Polish lecturers were more inclined than the Romanian ones towards monitoring the effects of their work.

According to the Social Identity Theory (SIT), attitudes towards foreigners are affected by the way a given person is classified either to one’s own group (in-group) or to a foreign one (out-group) (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Groves & Feyerherm, 2011; Leung & Wang, 2015; Stahl et al. 2010; Verhoeven et al., 2017). Such a bipolar division leads to a number of cognitive misrepresentations, viz: extreme attribution error (Pettigrew, 2001) and, what is more upsetting, favoring members of one’s group and discarding those that belong to a foreign one (Brewer & Miller, 1996). This makes the role of a leader so significant. A leader should provide a model for addressing diversity. This can be done by means of an open approach, which is aimed at groundbreaking and drawing benefits from the observed differences, rather than a distrustful attitude that emphasizes the dominance of the group or a disregarding approach towards the issues of cultural heterogeneity. A leader should promote development, show prospects for the future, encourage teammates to cooperate, adopt a task-oriented approach, as well as concentrate on objectives that stamp out differences and barriers (Stańda, 2003).

Conclusions

Many contemporary organisations face complex projects, which forces a shift from traditional forms of work organisation engaging individual capacities to those that incorporate teamwork at all corporate levels (Salas et al., 2008; Knapp, 2010; Zaccaro et al., 2012; Salas et al., 2015). In order to successfully accomplish intricate work tasks an individual is required to prove extensive knowledge and various skills. By such means teammates closely rely on each other and the context of their work (Yukl, 2010).

Having analyzed responses provided by the students and lecturers, it can be concluded that the effectiveness of a culturally complex team can be raised by, inter alia, training on cultural awareness with an aim to develop intercultural competences. Such tutoring may help to familiarise team members with similarities and differences between them and avoid future misunderstandings. However, what is important in the process of team formation is to build trust among teammates, as well as between the leader and his or her subordinates. This leads to an atmosphere full of tolerance and respect, where team members may share their ideas without a fear of being ridiculed. Such an environment allows for expressing different, even contrasting opinions, and boosting creativity. Such teams are required to have a common experience and shared goals among the members. For the team to expect considerable effects of work, all its members must be willing to cooperate, communicate openly and have a clear understanding of tasks. Additionally, an effective team should be characterised by good atmosphere and tolerance towards other cultures (Szydło & Widelska, 2018). Its members should at best be self-motivated, flexible, open to change, trust other members, comply with established rules of conduct and be open to draw inspiration from defined differences (Koheler, 2016).

In selecting team members, it is essential to take caution towards an even cultural distribution, which prevents from cultural domination and, ultimately, ensures the success of the team. Also, a team should be assigned a clear objective that gives it a proper direction and justifies the reason it exists. For the team to fully use its potential, it is crucial to build a flat, flexible structure and create a participatory system of management.

Acknowledgment

The project is financed by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange as part of the International Academic Partnerships (project PPI/APM/2018/1/00033/U/001).

References

- Ang S., & Van Dyne L. (2008), ‘Conceptualization of Cultural Intelligence: Definition, Distinctiveness, and Nomological Network’, In: S. Ang, & L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications, M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY, pp. 3-15.

- Aritz J., Walker R., Cardon P.W. (2017), ‘Media Use in Virtual Teams of Varying Levels of Coordination’, Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, vol. 81, no 1.

- Boyraz M. (2019), ‘Faultline’s as the “Earth’s Crust”: The role of team identification, communication climate, and subjective perceptions of subgroups for global team satisfaction and innovation’, Management Communication Quarterly, 33(4), pp. 581-615.

- Brewer M.B., Miller N. (1996), ‘Intergroup relations’, Open University Press, Buckingham.

- Burakova M., Filbien M. (2020), ‘Cultural intelligence as a predictor of job performance in expatriation: The mediation role of cross-cultural adjustment’, Pratiques Psychologiques, 26 (1), 1-17.

- Charry K. (2012), ‘Leadership Theories – 8 Major Leadership Theories’, Retrieved from http://psychology.about.com/od/leadership/p/leadtheories.htm.

- Connaughton S.L., Shuffler M. (2007), ‘Multinational and multicultural distributed teams: A review and future agenda’, Small Group Research, 38(3), pp. 387-412.

- Costa A.C., Fulmer A.C., Anderson N.R. (2017), ‘Trust in Work Teams: An Integrative Review, Multilevel Model and Future Directions’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, vol. 39, no 2.

- DeRue D.S., Nahrgang J.D., Wellman N., Humphrey S.E. (2011), ‘Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and metaanalytic test of relative validity’, Personnel Psychology, 64, pp. 7-52.

- Earley P.C., Ang S. (2003), ‘Cultural intelligence: Individual interactions across cultures’, Palo Alto, Stanford University Press, CA.

- Edmondson A.C. (2012), ‘Teaming: How organizations learn, innovate, and compete in the knowledge economy’, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, CA.

- Edmonson A.C., Harvey J.F. (2018), ‘Cross-boundary teaming for innovation: Integrating research on teams and knowledge in organizations’, Human Resources Management Review, 28, pp. 347-360.

- Eklund K.E., Barry E.S., Grunberg N.E. (2017), ‘Gender and Leadership’, In: A. Alvinius (Ed.), Gender differences in different contexts, 129-150.

- Eva N., Newman A., Miao Q., Copper B., Herbert K. (2019), ‘Chief executive officer participative leadership and the performance of new venture teams’, International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 37(1), pp. 69-88.

- Gadomska-Lila K., Rudawska A., Moszoro, B. (2011), ‘Rola lidera w zespołach wielokulturowych’ [The role of the leader in multicultural teams], Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie, XII (4), 7-20.

- Gajendran R.S., Harrison D.A. (2007), ‘The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown about Telecommuting: Meta-analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences’, Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 92.

- Gerpott F.H., Van Quaquebeke N., Schlamp S., Voelpel S.C. (2019), ‘An Identity Perspective on Ethical Leadership to Explain Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Interplay of Follower Moral Identity and Leader Group Prototypicality’, Journal of Business Ethics, 156, pp.1063–1078.

- Gibb C.A. (1954), ‘Leadership’, In: G. Lindzey (Ed.), Handbook of Social Psychology, vol. 2, pp. 877-917.

- Groves K.S., Feyerherm A.E. (2011), ‘Leader cultural intelligence in context: Testing the moderating effects of team cultural diversity on leader and team performance’, Group & Organization Management, 36(5), pp. 535-566.

- Harrison C. (2018), ‘Leadership Research and Theory’, In: Leadership Theory and Research, pp.13-52.

- Higgs M. (1996), ‘Overcoming the problems of cultural differences to establish success for international management teams’, Team Performance Management: an International Journal, (2)1, pp. 36-43.

- Katz D., Kahn R.L. (1978), ‘The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.)’, Wiley, New York.

- Knapp R. (2010), ‘Collective (Team) Learning Process Models: A Conceptual Review’, Human Resource Development Review, vol. 9, 3, pp. 285-299.

- Koheler R. (2016), ‘Optimization of Leadership Style. New Approaches to Effective Multicultural Leadership in International Teams’, Springer Gabler.

- Koźmiński A., Piotrowski W. (Eds.), (2000), ‘Zarządzanie. Teoria i praktyka’ [Management. Theory and practice], PWN, Warszawa.

- Kożusznik B. (2005), ‘Kierowanie zespołem pracowniczym’ [Managing a team of employees], PWE, Warszawa.

- Kraft M.H.G. (2018), ‘Antecedents & Perspectives of Ambidextrous Leadership’, Marketing and Management of Innovations, 4, pp. 5-13.

- Kuc B. (2006), ‘Od zarządzania do przywództwa’ [From management to leadership], Wydawnictwo Menedżerskie PTM, Warszawa.

- Lee M.C.C., Idris M.A., Tuckey M. (2019), ‘Supervisory coaching and performance feedback as mediators of the relationships between leadership styles, work engagement, and turnover intention’, Human Resource Development International, 22(3), pp. 257-282.

- Leung K., Wang J. (2015), ‘Social processes and team creativity in multicultural teams: A socio-technical framework’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, pp. 1008-1025.

- Matveev A. (2017), ‘Intercultural Competence in Organizations: A Guide for Leaders, Educators and Team Players’, Springer, Switzerland.

- Pettigrew T. (2001), ‘The ultimate attribution error: Extending Allport’s cognitive analysis of prejudice, Intergroup relations: Essential readings’, Hogg, M. A. and Abrams D., Psychology Press, New York.

- Piotrowski K., Świątkowski M. (2000), ‘Kierowanie zespołami ludzi’ [Leading teams of people], Dom Wydawniczy Bellona, Warszawa.

- Puni A., Mohammed I., Asamoah E. (2018), ‘Transformational leadership and job satisfaction: the moderating effect of contingent reward’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 39(1), pp. 522-537.

- Rockstuhl T., Seiler S., Ang S., Van Dyne L., Annen H. (2011), ‘Beyond General Intelligence (IQ) and Emotional Intelligence (EQ): The role of Cultural Intelligence (CQ) on cross-border leadership effectiveness in a globalized world’, Journal of Social Issues, 67(4), pp. 825-840.

- Salas E., Cooke N.J., Rosen M.A. (2008), ‘On teams, teamwork, and team Performance: Discoveries and developments’, Human Factors, 50(3), pp. 540-547.

- Salas E., Shuffler M.L., Thayer A.L., Bedwell W.L., Lazzara E.H. (2015), ‘Understanding and improving teamwork in organizations: A scientifically based practical guide’, Human Resource Management, 54(4), pp. 599-622.

- Samul J. (2019), ‘Spiritual Leadership: Meaning in the Sustainable Workplace’, Sustainability, 12(1), pp.1-16.

- Samul J., Zaharie M., Pawluczuk A., Petre, A. (2020), ‘Leading and developing virtual teams: practical lessons learned from university students’, Publishing House of Bialystok University of Technology, Białystok.

- Samul J., Szpilko D., Szydło J. (2021), ‘Samoprzywództwo i zaufanie a wyniki wirtualnej pracy zespołowej’ [Self-leadership and Trust and the Results of Virtual Teamwork], Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Krakowie, nr 1(991), 89–104.

- Sharma M.K., Jain, S. (2013), ‘Leadership Management: Principles, Models and Theories’, Global Journal of Management and Business Studies, vol. 3, pp. 309-318.

- Stańda A. (2003), ‘Przywództwo kierownicze w wymiarze kultury organizacyjnej’ [Managerial leadership in the organisational culture dimension], Zeszyty Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej w Poznaniu, 36, pp. 314-319.

- Szydło J. and Widelska U. (2018), ‘Leadership values – the perspective of potential managers from Poland and Ukraine (comparative analysis)’, Business and Management 2018: The 10th International Scientific Conference, Vilnius.

- Szydło J., Szpilko D., Rus C., Osoian C. (2020), ‘Management of muliticultural teams: practical lessons learned from university students’, Publishing House of Bialystok University of Technology, Białystok.

- Stahl G.K., Maznevski M.L., Voigt A., Jonsen K. (2010), ‘Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta‐analysis of research on multicultural work groups’, Journal of International Business Studies, 41, pp. 690-709.

- Tajfel H., Turner J.C. (1986), ‘The social identity theory of intergroup behavior’, In: W.G. Austin, S. Worhel (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations, Nelson Hall, Chicago, pp. 7-24.

- Tang N., Wang Y. (2017), ‘Cross‐cultural teams’, In: E. Salas, R. Rico & J. Passmore (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Team Working and Collaborative Processes, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chapter 10, pp. 219-242.

- Van Saane J. (2019), ‘Personal Leadership as Form of Spirituality’, In: J. Kok & S. van den Heuvel (Eds.), Leading in a VUCA World. Contributions to Management Science, Springer, Cham, pp. 43-57.

- Van Velsor E., McCauley C.D., Ruderman M.N. (Eds.), (2010). ‘The center for creative leadership handbook of leadership development’, Jossey-Bass, San Fransico.

- Verhoeven D., Cooper T., Flynn M., Shuffler M.L. (2017), ‘Transnational team effectiveness’, In: E. Salas, R. Rico & J. Passmore (eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Team Working and Collaborative Processes, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2017, Chapter 4, pp. 73-101.

- Yukl G.A. (1989), ‘Leadership in organizations (2nd ed.)’, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Yukl G. (2010), ‘Leadership in organizations’, Pearson, Upple Saddle River.

- Zaccaro S.J., Bader P. (2003), ‘E-Leadership and the Challenges of Leading E-Teams: Minimizing the Bad and Maximizing the Good’, Organizational Dynamics, vol. 31, no 4.