Introduction

The role of educational institutions is crucial in the development of the human capital required for the advancement of any nation. The heart of any university is its academic staff whose roles are crucial and their number, quality and their effectiveness make the difference in university education (Nwadiani et al., 2002). It is a well-recognized fact that any organization is only considered to be as successful as its employees; therefore, universities must endeavour to preserve their workface in order to promote knowledge consistency, committed decisions, and a seamless and coordinated workflow.

Moreover, there has been a noticeable shift from human resource to human capital which consists of the knowledge, skills and abilities of the people employed in organization which is indicative of their value (Armstrong, 2009). This fact is more precisely proven in higher education institutions as faculty members are considered the most valuable human asset that can be a source of competitive advantage (Collins and Clark, 2003). Moreover, there is additional stress as for them to handle the demands of today’s problems; educators must work with balanced or steady emotions. Therefore, when employees leave their jobs, it is often a sign that something is going wrong.

It has been noted that the growing employment trend in the education sector has led to an increase in the competition among institutes to maintain their image and strategic advantage (Hussain, 2005). Consequently, due to the increasing employment opportunities in the higher education sector, retaining a capable faculty member has become vital, and if an organization fails in retaining its employees, it will suffer drastically (Day and Glick, 2000).

Our problem is that Egyptian universities in specific are facing extremely severe situations as a result of globalization’s constant and quick changes in technology that have affected the marketplace (Prager, 2003, Jones et al., 2007). The Egyptian revolution played a serious role in adding to this already complex situation. As a result, businesses understood that they needed to create a different and distinctive stance that would allow them to maintain a competitive advantage over their business rivals (Alniacik et al., 2011, Chiang and Birtch, 2011).

The main objective of this paper is to determine a conceptual framework about the turnover intentions in higher education, specifically in private universities in Egypt from a theoretical review and the methodology of case analysis. The interest of this paper is because although Egypt has made significant progress towards reviving its economic growth since the revolution, unemployment remains persistently high therefore impacting the value of higher education. The average turnover across large organizations is 536 employees per year, in medium- sized organizations the turnover reaches 20 employees per year, while in small-sized organizations the average decreases to five employees annually (Ezzat and Ehab, 2018). Out of 148 countries, Egypt ranked number 146 in terms of labor market efficiency in 2013-2014 (Creative Associates International, 2016).

This paper follows the following structure. Firstly, an analysis of the literature about the topic about the theories concerning turnover intention was reviewed. Next, the methodology used is explained. Thirdly, the information obtained from the case analysis using thematic analysis is written to discuss the results that will make it possible to propose hypotheses for future studies. Finally, a conclusion including the theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and future research.

Importance of the Research Problem

According to Zopiatis et al. (2014), turnover is becoming a chronic issue at every organisational level, regardless of the kind or size and till this day many studies emphasise the need of retaining significant talent, and this study is one of them.. Precisely, in the education filed human capital is exceedingly expensive to replace (Welch, 2017), and as a result, universitas and governments must react to talent turnover quickly and seriously (Jiang and Shen, 2018).

While public universities have large numbers of faculty members, it is difficult to recruit them to private universities because many preferred the mandate system that allows them to work in more than one college at a time. This further supports our claim that it’s important to study private universitas instead of public as the real problem of staff members’ leaving is in the private sector. Also, since private universitas don’t offer the same luxury of working in more than one college at a time, this limits the staff members’ income and makes the competition very fierce in the private sector.

Review of Literature

Recently, the high turnover rates in universities have led to a noticeable decrease in performance and consistency, and have affected various factors mainly student achievements. This is due to the fact that there is a shortage of qualified faculty members to provide the needed quality of education. Therefore, there has been great effort dedicated to trying to prevent turnover, and the first step towards that is to try to grasp the factors that lead an employee to consider leaving.

Employee Turnover Intention

Turnover intention has been defined as an individual’s behavioral intention to leave the organization (Mobley, 1977). Another definition of employee turnover intention is the likelihood of an employee to leave the current job he/she are doing (Ngamkroeckjoti et al., 2012). While a more recent definition is that turnover intention reflects a worker’s deliberate and intentional tendency to leave their job and the company (Maier et al., 2013).There have been some researchers who have stated turnover intention as an intended psychological readiness to leave the institutions (Griffeth et al., 2000, Alniacik et al., 2011)

The reason for the changing definitions throughout time is that the literature seldom offers a definite description of turnover intention, which is a result of people’s belief that the phrase is self-explanatory (Bester, 2012).

Academic Turnover Intention

One profession that has caught the eye of many researchers due to the fact that it has been experiencing high turnover are universities’ faculties (Nawaz et al., 2019). Working as an academic isn’t as simple as it seems, as was mentioned in a review by Musselin (2007) that the academic tasks have undergone critical changes.

She stated that the academic profession now is extended far beyond teaching and research “An in-depth investigation of academic work would probably have shown that many academics were already engaged in many other activities.” (Musselin, 2007, p. 3) This statement was also later supported by Hyde et al. (2013) that the academic professionalism and identity issues are getting more complex than ever. Furthermore, Gurin et al. (2002) noted that the roles of academicians were the beyond classroom environment where they are also expected to prepare students for the outside world.

Talent Management

Talent Management has also been defined as the “objective to ultimately nurture and maintain a talent pool of adequately skilled and engaged workforce” (Lewis and Heckman, 2006). It not only develops employees through continuous learning but also enables employees to grow and move to more challenging roles in order to keep them engaged.

When it comes to preserving the workforce talent, audits are conduced to ensure effective HR planning and availability of talents when needed (Botha et al., 2011). They aim to set off any alarm bells for any intention to quit (McCartney and Garrow, 2006).

Thus, when talent management practices are implemented, it not only helps preserve the workplace, but it proves that it has an interest in investing in its people. This may improve the psychological connection between an organization and its employees leading to lower turnover intentions (Narayanan, 2016).

Work-life Balance

Frone suggests that when employees attain work-life balance, this will lead to a more motivated workforce with better productivity and reduced absenteeism (Frone, 2003).Work-life balance has been found to have positive effect on both individual and organizational outcomes such as improved financial performance, employee satisfaction and productivity, and organizational commitment and attachment (Shanker and Bhatnagar, 2010).

Hence, when an organization fails to implement work life balance practices, it will lead to hampering employees’ motivation causing them to disclose withdrawal symptoms such as absenteeism and turnover (Hughes and Bozionelos, 2007). Additionally, it has been proven that when there is a conflict between work and personal life, employees will struggle to maintain a balance and eventually quit their jobs (Houston and Waumsley, 2003).

Organizational commitment

Organizational commitment has always been a subject of interest due to its association with employees’ turnover intention (Allen and Meyer, 1993). Based on Tett and Meyer’s (1993) studies, they found that organizational commitment contributes exclusively towards turnover intention cognitions. Furthermore, Griffeth et al. (2000) pointed out that organizational commitment would be a better indicator to overpower the findings of turnover intention.

Moreover, after viewing the literature on Human resource development, it can be concluded that organizational commitment lessens employees’ intentions to leave the organization (Meyer and Allen, 1997, Islam et al., 2013). On the contrary, it’s important to note that Saporna and Claveria (2013) found no relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intentions.

Reward systems

Reward system has been defined as a combination of financial rewards and non- financial rewards (Armstrong, 2002); financial rewards like cash incentives, and non-financial rewards such as recognition and appreciation. Concerning non-financial rewards, Mosley (2016) states that any organization that conducts recognition program will find a reduction in staff turnover and be able to maintain top talents. While Atiq and Bhatti (2014) found that there is a significant relationship between cash and employee turnover in different age groups and this is consistent with previous studies that support a relationship between extrinsic motivation and turnover intention (Ertas, 2015).

Leader-Member Exchange

According to many research studies, a supervisor’s support is vital to building employee performance in any workplace (Karatepe, 2013, Hsiao et al., 2015).When managers are successful in forming an effective leader-member exchange relationship, this will lead to employees viewing the psychological contract as fulfilled by the organization which in turn makes them less likely to leave the organization (Collins, 2010).

While preceding studies have stated that the quality of leader member exchange is negatively related to intended turnover (Ansari et al., 2007, Jordan and Troth, 2011) and actual turnover (Griffeth et al., 2000), it is important to note that other studies showed that the relationship between leader-member exchange and turnover has been statistically weak and unstable (Falkenburg and Schyns, 2007).

The main person that can influence how demanding or how satisfying itis is the supervisor (Gilbreath and Benson, 2004). It has been found that support from supervisors is able to minimize work role conflict, role ambiguity, and increase job satisfaction (Major and Lauzun, 2010). This is especially true in the academic field as instructors need their head of department and dean’s support when dealing with students and when trying to work on their research.

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction is a long standing factor that has great influnce on the work place. One of the earliest definitions of job satisfaction was in 1964 by Vroom who stated that job satisfaction is an orientation of emotions that employees possess towards a role they are performing at work (Vroom, 1964).

A longitudinal study was conducted by Vandenberg and Nelson (1999) and found that lower levels of job satisfaction predicted turnover intention while higher levels of job satisfaction predicted intention to stay. Their findings are consistent with various other studies that found that higher levels of job satisfaction led to a decreased turnover intention (Judge et al., 2002).

There are limited amounts of research based on job satisfaction in educational institutions and the studies that are conducted are usually focusing on the teaching performance and turnover in schools (Fang and Wang, 2006), but there is lack of similar studies among the university teaching staff. Thus, there is a need for empirical research in the higher education sector, especially universities.

Work Overload

Work overload has been known as having too much work in a certain amount of time (Conley and Woosley, 2000). Conley and Woosley in 2000 stated that resources and time were under role conflict; however, Glisson et al. (2006) found that work overload is now considered an isolated variable from role conflict.

When academic employees experience overload, this makes them consider other options such as leaving their job. Additionally, studies have shown that work overload influences the behavior and attitude of employees which has shown to reduce job satisfaction (Grunfeld et al., 2005) and increase turnover intention (Jex et al., 1992).

Methodology

The study took the form of interviews with fifteen academic staff members in Egyptian private universities which were invited to participate on the basis that they could provide a sufficiently representative sample to help formulate a conceptual framework for turnover Intention.

The reason behind choosing private universities for this study is that currently they possess a remarkable reputation and image in the Arab world and are attracting affluent students and talented instructors and staff members with skills that are very difficult to imitate (Alniacik et al., 2011). Moreover, the Minister of Higher Education in Egypt has announced that 60 new universities will be established over the coming 10 years, 20 of them state institutions and 40 being private, international and technological universities.

The Egyptian government is focusing on private institutions in order to encourage private investment in higher education, improve quality, fulfil the rising demand for higher education, and alleviate the challenges that Egyptians have when studying abroad. Egypt had 31 private institutions as of 2018, boosting the competition among universities to keep their faculty.

Case Study

An exploratory case study has been selected as the appropriate research method to the investigation presented here (Yin, 2003). Recently, the use of case studies for formal design education has been suggested (Breslin and Buchanan, 2008). Therefore it’s crucial to highlight that, in social science, there are various qualitative research methods that without a doubt have been increasingly accepted, with greater impact (Marshall and Rossman, 1988) and thus valuing the power of qualitative analysis (Eisenhardt, 1989). In recent years, the case study has made great progress as a qualitative research technique (Patton, 2002), and after reviewing the literature in social sciences, the use of case study research has been shown to be well developed and had systematic methods for conducting and validating the work. Finally, case studies are used to explore situations in which the intervention being evaluated has no clear, single set of outcomes (Yin, 2003) which is the case in this research paper.

Participants

For the data collected to be representative in a qualitative study, the chosen participants should have specific knowledge or critical characteristics in order to be able to answer the research question and shed light on the phenomenon (Bode et al., 2015). This is why the chosen sampling method was the purposive sampling as this is the ideal method when the researcher intends to interview participants who have specific information based on their professional experiences (Palinkas et al., 2015, Etikan, 2016).

Therefore, the researcher interviewed department heads and assistant deans who assess and evaluate their employees and are responsible for their progress as well as employees to understand their perspective of their job and understand what factors would make them leave. Participants were contacted over the phone and determined the appropriate time for them to conduct the interview.

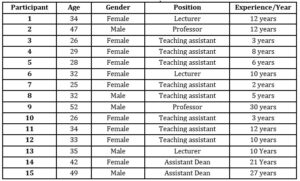

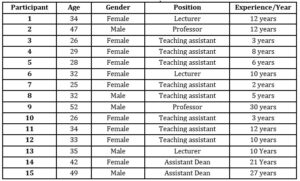

The chosen participants were 15 faculty members who are currently working in private universities. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the participants is presented in Table 1.1 below.

Table 1: Participant data

Authors’ own elaboration

Process of the Interviews

The data for the qualitative analysis were collected using an interview guide to make sure that all participants were asked the same questions, otherwise, as Guest et al. (2006) stated, it would be impossible to reach data saturation as it would be a constantly moving target.

Before the interview was conducted, all participants were asked to sign a letter of cooperation to make sure they understand the purpose of the interview, assure them that the data will be confidential and approve the recording of it. All interviews were recorded and conducted through a zoom meeting due to the current Covid-19 situation from July 2021 until December 2021 and lasted 30-45 minutes.

All recorded interviews were than transcribed in order to analyse the data to identify themes and help develop our conceptual model. After extensive reading of the transcripts, the researcher generated codes from the entire data using words and short phrases to reflect the participants’ narratives of their situations and points of view (Sutton and Austin, 2015). The coding process was manually performed and reorganized into various categories using a thematic analysis approach (Creswell, 2009).

Results of Case Analysis

Theme One: Unearthing common sources of turnover Intention

Talent Management

When asked if their talent and interest have been managed effectively by their university, most respondents agreed that the university administrative paid little attention to this matter. This has led many of them to be displeased with their current work status. Respondent one stated the following:

“I am not sure I was ever asked what my talents were and maybe that itself is the problem. We were never asked from our department head what skill or talent can we use and invest here. It was never brought up nor were there any attempts to help us develop ourselves”

This was further supported by responded five who commented that she feels there is no room for development.

“No, I used to think I have a good talent when to comes to interacting with students and in my courses, but my job has lately mismanaged me to a point where I have lost interest and I feel there is no room to develop. I was also interested to take a course in analysis to help my research skills but was told that due to budget cuts I would have to wait a for a while. I have been waiting three years now”

Respondent six who had finished her PhD two years ago added that the university’s only addition to her talent was encouraging her to finish her PhD but that was it. She was quoted saying the following:

“I am not sure my university has ever invested in me or shown the interest to hear out what my skills are. The extent of their invest is to help us receive our PhD and that’s it. As soon as we have it, they seem to forget about us.”

Work Overload

When asked to think of the first word that comes to their mind when they think of their job, 53% answered with their word “stressful” or “over worked”. Moreover, four respondents continued to state that if their job didn’t become less stressful and demanding then they will soon consider moving to another job. Respondent two was quoted saying:

“You are actually calling me on my way back from the university and I am completely exhausted. We had an audit visit today which my head of department called me to be part of last minute. I also had an 8:30 morning class and I am behind on correcting the midterm exams of my students. So now it’s 5:30 and I still have to go home and correct 75 individual assignments.”

While respondent four added to this point my saying:

“I am completely stressed out and it has made me doubt if I choose the right career path. I have to teach 18 hours per week along with an extra four hours per week for office hours to students who need help. I also need to work on my PhD, and I am required by my college to publish two papers per year. Besides my official working hours which are from 8:30 to 4:30 the college requires us to work after working hours if there any ISO or audit visit as well.

Respondent seven went on to add how lately she feels like she is not performing well at her job due to the many subjects she teaches.

“When you are overloaded and feel like you’re doing a million things at a time you sometime forget important stuff or submit things that aren’t the best quality to get done with it. For example, you can skip important content of the chapters because you are in a rush to finish the section as you have to submit a task to your dean.

Relationship with Manager

When the researcher asked the interviewees if they could change anything about their university what would it be, 10 out of the 15 respondents replied with “Management”. This is a crucial issue which could lead to employee turnover as Strachota et al. (2003) have found that employees who voluntarily left their jobs have stated the reason behind leaving was due to being dissatisfied with management support and having concerns regarding the lack of support. This is what the interviewees had to say about their management and how it has impacted them:

“The management always makes us feel like we are disposable, and I don’t like that all. I would like to feel more appreciated and have my views heard as some of us of good insight in the process of education due to our years of experience” (Respondent 3)

“Our head of department in my opinion doesn’t understand quite how to handle us. I believe that even paper work and extra working hours can be bearable with good management. It’s not what they ask but more of the way they say the things, the way they make you feel like you are obliged to all those extra things with no appreciation whatsoever.

We used to have better management that understood how to tell us stuff and how to handle our issue. Lately I feel that our head of department and even the dean don’t really have emotional intelligence.” (Respondent 1)

Recognition and Appreciation

Any employee wants to be appreciated and recognized for their work and faculty members are no expectation. When asked what makes them consider leaving their university, six of the interviewees said if they kept feeling unappreciated in their university.

“One of my major issue is the lack of appreciation. There is never any meeting to thank certain members, never an email to congratulate you on publishing a paper or anything. However, if you make the slightest mistake there will always be a meeting to remind you of your mistake. It is a little frustrating to be honest. (Respondent 8)

“I am a workaholic, and I will admit it. I enjoy working and will do any task you give me but there is a limit to who much I am willing to give when I receive almost nothing in return. I am not talking money because honestly, we are paid well but there is never a thank you for getting something done on time or even a simple good job. (Respondent 5)

Balancing Work with Family

Participants were asked about whether they found any difficulty with balancing their academic career with their personal life. Out of the 15 Participants ten of them agreed that this was definitely challenging at times. Respondent 12 who is currently working as a teaching assistant was quoted saying:

“Between all the paperwork, research hours and classes I sometimes go home emotional and physically drained. It is extra hard when you’re a woman with kids as they need constant attention and by the time I am home I don’t feel like I have the energy to give them what is needed. I am hoping this will be better once I have earned my PhD.”

While respondent one who is currently working as a lecturer elaborated more on this issue saying

“Now I could balance a little between work and my personal life after finishing my PhD but then again as an academic you always take work home weather its research, preparing for a course, correcting exams or supervising a PhD Student so it’s a tricky balance. I am sometimes able to work things out but most of the time it is defiantly a challenge.

Theme 2: What makes them stay at their current job?

Extrinsic Rewards

When asked what makes them stay at their current university, most of the interviews agreed that the reason they continued to work in their university is that the university offered an attractive financial package deal. Respondent number two said the following:

“My university pays me handsomely well especially after being a professor and that is defiantly one of the main reasons I have stayed so long. Also, I was able to have both of my children study here and received a 30% discount on their tuition fees. So overall it’s a good deal”

Moreover, respondent four who seemed to be unhappy with her current situation at the university said the only reason she hasn’t left was the university benefit program.

“We have great health insurance not to mention we get paid half our salary with dollars which is very uncommon here in Egypt. In spite of all the things I dislike about work the whole compensation package is too tempting to leave. I doubt I will find the same offer elsewhere”

Organizational Commitment

Some respondents have stated that the reason t they would not consider leaving is that they feel that they are committed to the University and they are proud to work there, this could be related to the fact that universities in Egypt usually hire from their graduate students, thus creating a sense of loyalty. Respondent 11 had this to say about her university:

I’ve been in this university since I was 17 as I started my undergraduate studies here as well as my master’s and I’m currently 34 so I’ve been here for over 15 years this place feels like home to me and I can’t imagine working anywhere else”

Respondent one went on when comparing her university to other universities and stated that she was proud to work in it; she was quoted saying:

“Although sometimes I have a love hate relationship with my job, I’m very proud to work here. It’s an institution that has a long history for several generations.”

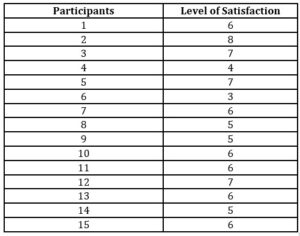

Theme 3: How satisficed are the faculty member at private universities?

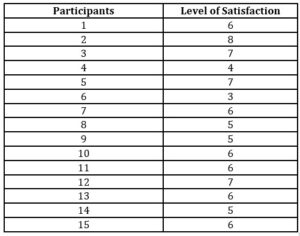

The interviewees were asked if they were satisfied at their current job, if yes, to what extent they felt satisfied (10 being the maximum and 1 being the minimum). Table 2 shows their responses.

Table 2: Level of Job Satisfaction

The majority of the respondents revealed that they were currently not satisfied with their job as they used to be. This is an alarming issue as was stated by Mobley’s model of turnover that when an employee is dissatisfied with their current job, he/she then quits if the new job is expected to be more satisfying. This could be a warning sign that if universities don’t work on improving employee satisfaction, they might find themselves losing their staff sooner than they expect. Furthermore, since the 50s until now various studies have shown that faculty satisfaction is an important predictor of faculty turnover intention (Rosser, 2004).

Case Discussion

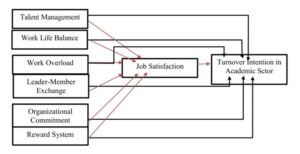

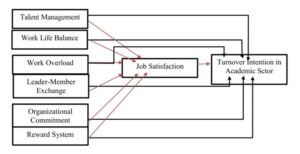

The main purpose of this academic paper was to investigate the likely turnover intention to be found among the faculty members of private universitas in Egypt. When thematic analysis was conducted, it turned out that to support past findings, talent management has an influence over reducing employee’s turnover intention (Oladapo, 2014). Moreover, it has been found that when talent management strategies have been implemented in educational institutions, it leads to effective identification of the core competencies required for the job description by the faculties, hence helping management by recruiting and selecting the most effective employees based on the suitable competencies which will lead to the right job to the right person (Tyagi et al., 2017). It’s no secret that recruiting effectively is the first step towards effective retention. Thus, we hypothesize:

H1: The better the implementing of talent management strategies in a company, the lesser the turnover intention in the academic sector.Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of work life balance which is constant with the finding of Hughes and Bozionelos (2007) who stated that when an organization fails to implement work life balance practices it will hamper employees’ motivation causing them to disclose withdrawal symptoms such as absenteeism and turnover. Although work life balance has received extensive research over the years, less focus has been given to the reality of work-life balance satisfaction in the higher educational sector (Noor, 2011). Balancing between work and one’s personal life is perceived as an important issue among workers globally and academics in higher education institutions were not excluded (Mohd Noor et al., 2009). Therefore, the following hypothesis is formed:

H2: There is a negative relationship between perceived work life balance and turnover intention in the academic sector.

Many participants stated that work overload was a major factor in making them consider leaving their job. This is in line with the findings of Bakker et al. (2005) who stated that work overload is considered to be emotional exhaustion and it is linked to leaving the workplace. This is furthermore constant with Hon’s (2013) research which concluded that work overload is a vital factor that leads to turnover intentions; based on that, we hypothesize the following:

H3: There is a positive relationship between work overload and turnover intention in the academic sector.

Previous studies have stated that quality of leader member exchange is negatively related to intended turnover (Ansari et al., 2007, Jordan and Troth, 2011). Chen and Wu (2017) found that when managers are successful in forming an effective LMX relationship, this will lead to employees viewing the psychological contract as fulfilled by the organization, which in turn makes them less likely to leave the organization. Furthermore, Yiu and Saner (2011) found relationships with immediate supervisors to contribute with 48% of employee turnover among employees. Accordingly, the following hypothesis was developed:

H4: Leader Member Exchange is negatively associated with turnover intention

Concerning the reasons why employees stay at their universities, this study found that organizational commitment played a major which is in line with Pryce-Jones (2010) where he concluded in his study of turnover intention on academic staff that academic staff members who have high level of commitment tend to stay in their job 75% longer than their colleagues or peers who do not think or feel the same way. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formed:

H5: There is a negative relationship between organizational commitment and the turnover intention in the academic sector

And the second reason was due to the reward system which is supported by the study done by Cotterell (2013) where it was shown that extrinsic motivations, such as salary increase, decrease the rate of turnover intention. Furthermore, Luna‐Arocas and Camps (2008) claimed that salary strategies negatively influence turnover intentions. Finally, Khan et al. (2011) claimed that when organizations ignore the importance of intrinsic rewards such as recognition and appreciation, it will have negative consequences on employee retention. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formed:

H6: There is a negative relationship between reward system and the turnover intention in the academic sector

The last theme discussed was the job satisfaction of faculty members and the results were alarming. From an organizational factor point of view, Noe et al. (2010) found that employees tend to withdraw from the organization when they are dissatisfied with the nature of the job, supervisors, or the employee’s own personality. While Magolego et al. (2013) discovered that talent management is a good predictor of job satisfaction. And finally According to Qureshi et al. (2012), perceived work overload causes greater stress and reduced job satisfaction.

Secondly, from a reward perspective, employee performance may be boosted and employees become more content with their jobs if effective incentive schemes are provided to them (Tahir et al., 2012). Finally, when examining individuals’ factors, it’s safe to assume that as work life balance focuses on balancing both the commitment of work and life that when employees who are pleased at home are more likely to be satisfied at work (Koubova and Buchko, 2013). Moreover, according to Wong and Law’s study, it was established that emotional intelligence promotes employees’ job satisfaction (Wong and Law, 2002). The problem of job satisfaction has affected higher education; therefore, educational leaders have been working on increasing the research on trying to identify the variables that influence job satisfaction (Truman State University, 1999, Grace and Khalsa, 2003).

Therefore, we conclude that job satisfaction is an important mediator to turnover intention in private universities. Thus, we hypothesize:

H7: Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between Talent Management, work life balance, Leader-member exchange, organizational commitment, work overload, reward system and turnover intention in the academic sector

Proposed Model:

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework

Conclusion

Theoretical Implications

This study can be useful to academicians and researchers who might be interested in pursuing research on factors influencing turnover intent in developing countries. The suggestions for further research will enable them to easily identify areas where more research activity will be required to better improve the social and emotional value of private educational institutions. More specifically, this research aims to minimize the gap in academic turnover intention as previous research has shown that theoretical and empirical evidence remains unsettling as previous studies were focused on developed nations where formal education institutions have been established since the early civilization.

Practical Implications

The findings of the study provide significant information to the management of how certain practices affect turnover intent in an organization and assist in pinpointing the reason why many faculty members are currently considering leaving their job. The government plays a very important role in

formulating policies that touch on employee welfare. The research results will enable the policy developers in the government and in the academic field to formulate policies which will improve the overall efficiency of staff employees. Therefore, when the universities are able to retain their employees, this will lead students to receive proper higher education which makes them more likely to live in ways that benefit all the surrounding communities improving the social status as in nations such as Egypt; academics serve as information gatekeepers and aid in the development of society especially in a social perspective (Jorfi et al., 2014).

Limitations

One of the main limitations of this study is that it’s a case study based on qualitative data which could mean that the interviewees’ responses can be subject to various problems of bias, poor recall, and inaccurate articulation (Yin, 2003). Therefore, the respondents who participated in the research may not necessarily be truly representative of the true population. Another limitation of this study is the focus of the educational industry and more specifically private universities.

Consequently, the generalizability of the conclusions may be limited to the specific situations explored. Finally, the current study was based on a cross-sectional design, and, thus, the cause-and-effect relationship testing is not permitted through this one- time measure.

Recommendations and future research

Future research could include deep empirical research in the University status of both public and private universities and could be done through conducting both qualitative and quantitative study. The quantitative study would distribute a questionnaire to a larger sample group of faculty members in Egypt. It would also be interesting to see the influence of gender differences as a predictor of turnover intention. Moreover, this study made no distinction between the small, medium, and large universitas, therefore, it is recommended that similar future research should account for the variable sizes of the universities.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Nadeen AbouDahab, upon reasonable request

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Allen, N. J. & Meyer, J. P. (1993) ‘Organizational commitment: Evidence of career stage effects?’, Journal of Business Research, 26, 49-61.

- Alniacik, U., Cigerim, E., Akcin, K. & Bayram, O. (2011) ‘Independent and joint effects of perceived corporate reputation, affective commitment and job satisfaction on turnover intentions’, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 1177-1189.

- Ansari, M., Kee, D. & Aafaqi, R. (2007) ‘Leader-member exchange and attitudinal outcomes: Role of procedural justice climate’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 28, 690-709.

- Armstrong, M. (2002) Employee reward, CIPD Publishing, London.

- Armstrong, M. A. (2009) Handbook of human resource management practice, Kogan Page Publishers, London.

- Atiq, M. & Bhatti, A. (2014) ‘The impact of incentives on Employees turnover at Pakistan International Container Terminal Limited (“PICT”) with respect to the different age brackets’, IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 16, 53-60.

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E. & Euwema, M. C. (2005) ‘Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout’, Journal of occupational health psychology, 10, 170-80.

- Bester, F. (2012) A model of work identity in multicultural work settings.D Thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg.

- Bode, C., Singh, J. & Rogan, M. (2015) ‘Corporate Social Initiatives and Employee Retention’, Organization Science, 26, 1702-1720.

- Botha, A., Bussin, M. & Swardt, L. (2011) ‘An employer brand predictive model for talent attraction and retention’, SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 9, 1-12.

- Breslin, M. & Buchanan, R. (2008) ‘On the Case Study Method of Research and Teaching in Design’, Design Issues, 24, 36-40.

- Chen, T.-J. & Wu, C.-M. (2017) ‘Improving the turnover intention of tourist hotel employees: Transformational leadership, leader-member exchange, and psychological contract breach’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29, 1914-1936.

- Chiang, F. F. T. & Birtch, T. A. (2011) ‘Reward climate and its impact on service quality orientation and employee attitudes’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30, 3-9.

- Collins, C. & Clark, K. (2003) ‘Strategic Human Resource Practices, Top Management Team Social Networks, and Firm Performance: The Role of Human Resource Practices in Creating Organizational Competitive Advantage’, Academy of Management Journal, 46, 740-751.

- Collins, M. D. (2010) ‘The effect of psychological contract fulfillment on manager turnover intentions and its role as a mediator in a casual, limited-service restaurant environment’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29, 736-742.

- Conley, S. & Woosley, S. A. (2000) ‘Teacher role stress, higher order needs and work outcomes’, Journal of Educational Administration, 38, 179-201.

- Cotterell, H. (2013) Employee turnover reduction through extrinsic rewards. Master Thesis, Aalto school of Economics.

- Creative Associates International (2016) Micro, small and medium enterprises in Egypt, Creative Associates International, Cairo.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, Sage Publications, Inc., London.

- Day, N. & Glick, B. (2000) ‘Teaching Diversity: A Study of Organizational Needs and Diversity Curriculum in Higher Education’, Journal of Management Education, 24, 338-352.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989) ‘Building Theories from Case Study Research’, Academy of Management Review, 14, 532-550.

- Ertas, N. (2015) ‘Turnover Intentions and Work Motivations of Millennial Employees in Federal Service’, Public Personnel Management, 44, 1-23.

- Etikan, I. (2016) ‘Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling’, American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5, 1.

- Ezzat, A. & Ehab, M. (2018) ‘The determinants of job satisfaction in the Egyptian labor market’, Review of Economics and Political Science, 4, 54-72.

- Falkenburg, K. & Schyns, B. (2007) ‘Work satisfaction, organizational commitment and withdrawal behaviors’, Management Research News, 30, 708-723.

- Fang, Y. & Wang, K. (2006) ‘Teaching Performance and Turnover: A Study of School Teachers in Singapore’, Employment Relations Record, 6, 1-30.

- Frone, M. R. (2003). Work-family balance.Quick, J. C. & Tetrick, L. E. (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (p.p. 143–162). American Psychological Association, USA.

- Gilbreath, B. & Benson, P. (2004) ‘The Contribution of Supervisor Behaviour to Employee Psychological Well-Being’, Organizational Leadership and Supervision Faculty Publications, 18, 255-266.

- Glisson, C., Dukes, D. & Green, P. (2006) ‘The effects of the ARC organizational intervention on caseworker turnover, climate, and culture in children’s service systems’, Child Abuse Negl, 30, 855-80.

- Grace, D. & Khalsa, S. (2003) ‘Re-recruiting faculty and staff: The antidote to today’s high attrition’, Independent school, 62, 20-27.

- Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W. & Gaertner, S. (2000) ‘A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium’, Journal of Management, 26, 463-488.

- Grunfeld, E., Zitzelsberger, L., Coristine, M., Whelan, T. J., Aspelund, F. & Evans, W. K. (2005) ‘Job stress and job satisfaction of cancer care workers’, Psychooncology, 14, 61-9.

- Guest, G., Bunce, A. & Johnson, L. (2006) ‘How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability’, Field methods, 18, 59-82.

- Gurin, P., Dey, E., Hurtado, S. & Gurin, G. (2002) ‘Diversity and higher education: Theory and impact on educational outcomes’, Harvard educational review, 72, 330-367.

- Hon, A. H. Y. (2013) ‘Does job creativity requirement improve service performance? A multilevel analysis of work stress and service environment’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 161-170.

- Houston, D. & Waumsley, J. (2003) Attitudes to flexible working and family life, JRF Policy Press, New York.

- Hsiao, C., Lee, Y.-H. & Chen, W.-J. (2015) ‘The effect of servant leadership on customer value co-creation: A cross-level analysis of key mediating roles’, Tourism Management, 49, 45-57.

- Hughes, J. & Bozionelos, N. (2007) ‘Work-life balance as source of job dissatisfaction and withdrawal attitudes: An exploratory study on the views of male workers’, Personnel Review, 36, 145-154.

- Hussain, I. (2005) ‘Education, employment and economic development in Pakistan’, Education Reform in Pakistan: Building for the Future, 33-45.

- Hyde, A., Clarke, M. & Drennan, J. (2013). The changing role of academics and the rise of managerialism.Kehm, B. & Teichler, U. (Eds.), The Academic Profession in Europe – New Tasks and New Challenges (p.p. 39-52). Springer, New York.

- Islam, T., Khan, S.-u.-R., Ahmad, U. & Ahmed, I. (2013) ‘Organizational learning culture and leader-member exchange quality: The way to enhance organizational commitment and reduce turnover intentions’, The Learning Organization: An International Journal, 20, 322-337.

- Jex, S. M., Beehr, T. A. & Roberts, C. K. (1992) ‘The meaning of occupational stress items to survey respondents’, The Journal of applied psychology, 77, 623-8.

- Jiang, H. & Shen, H. (2018) ‘Supportive organizational environment, work-life enrichment, trust and turnover intention: A national survey of PRSA membership’, Public Relations Review, 44, 681-689.

- Jones, E., Chonko, L., Rangarajan, D. & Roberts, J. (2007) ‘The role of overload on job attitudes, turnover intentions, and salesperson performance’, Journal of Business Research, 60, 663-671.

- Jordan, P. J. & Troth, A. (2011) ‘Emotional intelligence and leader member exchange: The relationship with employee turnover intentions and job satisfaction’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 32, 260-280.

- Jorfi, H., Jorfi, S., Fauzy, H., Yaccob, B. & Nor, K. M. (2014) ‘The impact of emotional intelligence on communication effectiveness: Focus on strategic alignment’, African Journal of Marketing Management, 6, 82-87.

- Judge, T. A., Parker, S. K., Colbert, A. E., Heller, D. & Ilies, R. (2002). Job satisfaction: A cross-cultural review.Anderson, N., Ones, D. S., Sinangil, H. K. & Viswesvaran, C. (Eds.), Handbook of industrial, work and organizational psychology. Vol. 2 (p.p. 25–52). Sage Publications, Inc., London.

- Karatepe, O. (2013) ‘High-performance work practices, work social support and their effects on job embeddedness and turnover intentions’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25, 903-921.

- Khan, R. I., Aslam, H. D. & Lodhi, I. (2011) ‘Compensation Management: A strategic conduit towards achieving employee retention and Job Satisfaction in Banking Sector of Pakistan’, International journal of human resource studies, 1, 89.

- Koubova, V. & Buchko, A. (2013) ‘Life-work balance: Emotional intelligence as a crucial component of achieving both personal life and work performance’, Management Research Review, 36, 700-719.

- Lewis, R. E. & Heckman, R. J. (2006) ‘Talent management: A critical review’, Human resource management review, 16, 139-154.

- Luna‐Arocas, R. & Camps, J. (2008) ‘A model of high performance work practices and turnover intentions’, Personnel Review, 37, 26-46.

- Magolego, H., Barkhuizen, E. & Lesenyeho, D. Talent management and job performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction. 30th Pan Pacific Conference 3–6 June, 2013 Johannesburg. PPBA, 132–235.

- Maier, C., Laumer, S., Eckhardt, A. & Weitzel, T. (2013) ‘Analyzing the impact of HRIS implementations on HR personnel’s job satisfaction and turnover intention’, The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 22, 193-207.

- Major, D. & Lauzun, H. (2010) ‘Equipping Managers to Assist Employees in Addressing Work-Family Conflict: Applying the Research Literature toward Innovative Practice’, The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 13, 69-85.

- Marshall, C. Y. & Rossman, G. B. (1988) Desingning qualitative research, Sage Publictions, New York.

- McCartney, C. & Garrow, V. (2006) The talent management journey, Roffey Park Institute, Horsham.

- Meyer, J. P. & Allen, N. J. (1997) Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application, SAGE Publications, Inc., New York.

- Mobley, W. H. (1977) ‘Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover’, Journal of applied psychology, 62, 237-240.

- Mohd Noor, K., Stanton, P. & Young, S. 2009. Work-life balance and job satisfaction: a study among academics in Malaysian higher education institutions. 14th Asia Pacific management conference. Waseda Campus of Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan.

- Mosley, E. (2016) 3 ways that recognition reduces employee turnover [Online]. Available: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-mosley/3-ways-thatrecognition-r_b_7965532.html.

- Musselin, C. (2007) ‘The Transformation of Academic Work: Facts and Analysis’, Center for Studies in Higher Education, UC Berkeley, University of California at Berkeley, Center for Studies in Higher Education, 1-16.

- Narayanan, A. (2016) ‘Talent management and employee retention: Implications of job embeddedness-a research agenda’, Journal of Strategic Human Resource Management, 5, 34-40.

- Nawaz, M., Siddiqui, S., Rasheed, R. & Iqbal, S. M. J. (2019) ‘Managing Turnover Intentions among Faculty of Higher Education Using Human Resource Management and Career Growth Practices’, Review of Economics and Development Studies, 5, 119.

- Ngamkroeckjoti, C., Ounprechavanit, P. & Kijboonchoo, T. Determinant factors of turnover intention: A case study of air conditioning company in Bangkok, Thailand. International Conference on Trade, Tourism and Management, 2012 Thailand. 21-22.

- Noe, R., Hollenbeck, J., Gerhart, B. & Wright, P. (2010) Fundamentals of human resource management, McGraw-Hill/Irwin, New York.

- Noor, K. M. (2011) ‘Work-life balance and intention to leave among academics in Malaysian public higher education institutions’, International journal of business and social science, 2, 240-248.

- Nwadiani, D., Akpotu, D. & Ejiro, N. (2002) ‘Academic staff turnover in Nigerian Universities (1990-1997)’, Education, 123, 235-281.

- Oladapo, V. (2014) ‘The impact of talent management on retention’, Journal of business studies quarterly, 5, 19.

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N. & Hoagwood, K. (2015) ‘Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research’, Adm Policy Ment Health, 42, 533-44.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002) Qualitative research & evaluation methods, Sage Publications, Inc., London.

- Prager, H. (2003) ‘Gaining a competitive advantage through customer service training’, Industrial and commercial training, 35, 259-262.

- Pryce-Jones, J. (2010) Happiness at work: Maximizing your psychological capital for success, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Qureshi, M. I., Jamil, R., Iftikhar, M., Arif, S., Lodhi, S., Naseem, I. & Zaman, K. (2012) ‘Job Stress, Workload, Environment and Employees Turnover Intentions: Destiny or Choice’, Archives of Sciences, 65, 230-240.

- Rosser, V. J. (2004) ‘Faculty members’ intentions to leave: A national study on their worklife and satisfaction’, Research in higher education, 45, 285-309.

- Saporna, G. & Claveria, R. (2013) ‘Exploring the Satisfaction, Commitment and Turnover Intentions of Employees in Low Cost Hotels in Or. Mindoro, Philippines’, Journal of Tourism Research & Hospitality,

- Shanker, T. & Bhatnagar, J. (2010) ‘Work Life Balance, Employee Engagement, Emotional Consonance/ Dissonance &Turnover Intention’, Indian journal of industrial relations, 74-87.

- Strachota, E., Normandin, P., O’Brien, N., Clary, M. & Krukow, B. (2003) ‘Reasons registered nurses leave or change employment status’, The Journal of nursing administration, 33, 111-7.

- Sutton, J. & Austin, Z. (2015) ‘Qualitative Research: Data Collection, Analysis, and Management’, The Canadian journal of hospital pharmacy, 68, 226-31.

- Tahir, S., Yusoff, R., Azam, K., Khan, A. & Kaleem, S. (2012) ‘The effects of work overload on the employees’ performance in relation to customer satisfaction: A case of Water & Power Development Authority, Attock, Pakistan’, World Journal of Social Sciences, 2, 174-181.

- Tett, R. P. & Meyer, J. P. (1993) ‘Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta‐analytic findings’, Personnel psychology, 46, 259-293.

- Truman State University (1999) Retention of quality professors: Key to a successful liberal arts education?, American Association of University Professors, Kirksville, MO.

- Tyagi, S., Singh, G. & Aggarwal, T. (2017) ‘Talent management in education sector’, International Journal on Cybernetics & Informatics (IJCI), 6, 47-52.

- Vandenberg, R. J. & Nelson, J. B. (1999) ‘Disaggregating the motives underlying turnover intentions: When do intentions predict turnover behavior?’, Human Relations, 52, 1313-1336.

- Vroom, V. H. (1964) Work and Motivation, Wiley Publishing House, New York.

- Welch, G. (2017) ‘Reducing CMO turnover: A recruiter’s prescription’, Harvard Business Review, 95, 59-59.

- Wong, C.-S. & Law, K. S. (2002) ‘The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study’, The Leadership Quarterly, 13, 243-274.

- Yin, R. (2003) Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Sage, London.

- Yiu, L. & Saner, R. (2011) ‘Talent recruitment, attrition and retention: strategic challenges for Indian industries in the next decade’, Centre for Socio-Eco-Nomic Development, 1-14.

- Zopiatis, A., Constanti, P. & Theocharous, A. L. (2014) ‘Job involvement, commitment, satisfaction and turnover: Evidence from hotel employees in Cyprus’, Tourism Management, 41, 129-140.