Introduction

Merging results, managerial balancing is the most tangential issue of superiors in organizations in times of crisis by evolving individual approaches, managing at all levels in terms of selecting, supporting, motivating and training employees optimally and building better and safe workplaces, and fostering healthy behaviour amid crisis while helping businesses in designing products (OECD, 2019). Managerial support should generally be implemented by company policies and regulations amid crisis to apply clear strategies of leading employees and keep them motivated (Wolor et al., 2020).

Motivation can be understood as goal-oriented behavior. A person is motivated when he expects the achievement of a certain goal as a result of certain actions. It is an activating, directional process that determines the selection and strength of the implementation of behavioral tendencies (Baumeister, 2016), fundamentally meant to facilitate behavioral alteration, and as well a force that enables an individual to act in the direction of a particular objective.

Motivation is an internal process. Whether we define it as a drive or a need, motivation is a condition inside us that desires a change, either in the self or the environment. When we tap into this well of energy, motivation endows the person with the drive and direction needed to engage with the environment in an adaptive, open-ended, and problem-solving sort of way (Reeve, 2015).

Effective motivation supports not only higher productivity, job satisfaction and loyalty, but also reduces fluctuations and absence of employees. Values, needs and personal characteristics are necessary to know to stimulate more effective motivation. Effective employee motivation requires managers to apply individual approach while taking into account situational factors. Above all, it must be regarded that the needs and motivational factors of the generation are different.

Baby-Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, are more committed to their roles than other generations have preference for structure and discipline, characterized as being workaholics and are considered good team players. Professionals are regarded as excellent mentors to their colleagues and juniors in the organization. Baby Boomers are competitive and need recognition while rewards keep them motivated to achieve more. They are less tech savvy compared to the younger generations and have difficulties to keep up with developments.

The generation X, born between 1965 and 1976, are characterized as overall workers. They are committed to juggling work with family time and favoring work-life balance in an organization. They value being able to do things quickly and don’t prefer spending overtime completing something perfectly and less satisfied with senior management.

The generation Y, born between 1977 and 1994, are considered the most independent workers and are concerned with ethics and the social responsibility of the organization they work for. Their strengths of sourcing information are followed by their need to create their own processes rather than being told exactly what to do. Due to their independent nature, they do not favor teamwork. The generation y do not have a strong work ethic and work less hours a week compared to the older generation and they are impatient related to their work growth and are likely to leave if their skills are not being developed.

The generation Z, born between 1995 and 2010, is the most tech competent generation. They are able to multitask and to pick up new developments quicker than the older generations. They are ambitious and striving the goal of climbing to the top of their profession to start their own business. The generation Z favor a realistic outlook compared to the generation Y having more of idealism. The generation Z are too much reliant on technology solving problems.

While the generation Z is very professional in digital communication and technique, the generation of baby boomers is more often unskilled in technique and needs to be trained. In contrast, the baby boomers consider work as an exciting adventure, the generation X focusing work as a difficult challenge (Srinivasan, 2012; Rump and Eilers, 2015)

Generation Z places greater emphasis on enjoying one’s work, quality of relationship with co-workers, and achieving one’s goals as motivational factors (Kirchmayer and Fratričová, 2016). Generation Y places a slightly higher value on leisure time – so they are likely to be correspondingly receptive to an optimised work-life balance.

For individual factors, the generation Y has higher score than baby boomers and generation X. For knowledge sharing, the generation X has higher score than baby boomers and generation Y. The online knowledge sharing is dominant for baby boomers and generation X, while for generation Y the offline knowledge sharing is dominant. This is surprising because based on theory, the generation Y is more familiar with information technology than baby boomers and generation X. This result needs further investigation. For individual work performance, the baby boomers have higher score than generation X and generation Y. It means that the more senior the generation is, the higher the impact of knowledge sharing on individual work performance is (Kurniawati et al., 2016).

Each generation is uniquely valuable to the workforce. If managers want to motivate each generation, they should know their personalities, their needs and preferences. Understanding their strengths and weaknesses, leaders can identify key training and development opportunities towards their unique strengths and help them filling potential skill gaps.

Theoretical Background

Ancient theories of the 20th and 21st centuries have started to analyse and describe motivation. Theory of optimal level by Claude Bernard defines motivation with hedonistic approach of achieving and maintaining the optimal level, level of equilibrium which gives pleasure. Disequilibrium leads to displeasure. He postulated that every individual strives to avoid disequilibrium by maintaining optimal level of the needs like food, water or body temperature (Holmes, 1986). Psychoanalytic Theory by Sigmund Freud explains that inborn tendencies, instincts, influence individual behavior. Having life and death instincts is individually weighted in a person. Life instincts are constructive and death instincts are destructive. After him unconscious motives determine our behavior. Humanistic theory by the important researchers Maslow and Rogers deals with the desire of individuals to realize their potentials, strengthening self-confidence and attain ideal self. According to Maslow, every individual aspires to fulfil basic needs first, followed by safety, love, esteem and finally actualization needs. Carl Rogers explained all human beings having a natural incentive for learning, growing and progress as self-actualizing tendency (Rudolph, 2013).

The topic of motivation is more discussed in the subject of organizational behavior, which contains a variety of models and theories of researchers, e.g., Maslow, Alderfer, McClelland, Hackman and Hertzberg, who reflected that development and growth of employees is significantly focused by individuals that exploit the potential of employees. The main focus lies on motivation by achievement.

Motivation theories, developed since the 1930s, classified into content, process and action theory, are different models defined by different explanations evolving into motivation. Content theories explain what motivation is, and process theories describe how motivation occurs. Furthermore, cognitive theories explain how individuals’ way of thinking and perceiving themselves and their environment influence their motives. These theories explain how individual mental constructs can increase actions for achieving goals. Theories of motivation are applied in sectors, as organizations and companies using incentives to increase employee performance and performance psychology, sports, education and learning using affect as a trigger of human behavior.

The process theories deal with the question of how motivation influences behavior. Process theories of motivation try to explain why behaviors are initiated. These theories focus on the mechanism by which we choose a target, and the effort that we exert to “hit” the target. There are four major process theories: operant conditioning, equity, goal, and expectancy-oriented process theory. Operant conditioning, evolved by B.F. Skinner in the year 1953, focuses on the learning of voluntary behaviors (Scholz, 2009). The common four types of reinforcement schedules are fixed ratio, variable ratio, fixed interval, variable interval. The aspiration of practitioners is to design individual reinforcement plans to manage a specific behavior of individuals or teams to achieve goals, while preventing that targeted behavior from disappearing. The equity theory, explained by J.S. Adams in 1965, states that motivation is affected by the outcomes that could be receive for one’s inputs compared to the outcomes and inputs of other people. This theory is concerned with the reactions people have to outcomes they receive as part of a social exchange (Acatrinei, 2016)

The goal theory after E.A. Locke in 1978 stated that people will perform better if they have difficult, specific, accepted performance goals or objectives (Acatrinei, 2016).

The expectancy theory of V.H. Vroom 1964 has three components: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. Concerning expectancy is the individuals’ belief that effort will lead to the intended performance goals. Instrumentality is the belief that a person will receive a desired outcome if the performance expectation is met and valence is the unique value an individual places on a particular outcome; we will exert much effort to perform at high levels while expecting to obtain unique valued outcomes (Acatrinei, 2016).

The theory of control focuses on how feedback affects effort toward goals (Klein, 1989). The following steps are involved: 1. Set goal, 2. Receive feedback, 3. Compare feedback on performance to the goal, 4. In response to the discrepancies between feedback and the goal, individuals will either: a. modify behavior (e.g., work harder) or b. modify the goal.

The theory of action is the analysis of the situation in which the motivation arises. The motivation can have its origin in increased demands on oneself, or, due to the interaction with the manager, arise from a challenging task or result from the social environment. The focus is not only on one’s own working group, but also on the entire organization and society (Raabe, Frese and Beehr, 2006)

In terms of job satisfaction, the content theories, such as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Alderfer’s ERG theory, Herzberg’s Two factors Theory, and McClelland’s Theory of Needs have high demand on satisfaction on job-related factors causing the existence of motivation, as supported by Chicu (2015), whose results of exploratory study concluded that better Human Resources practices, in terms of job design and discretion, will improve job satisfaction among employees. Considering measurement of discretion as extent of discretion over work tasks, discretion over methods of work and discretion over speed of work, while job design was measured as percentage of employees working in self-managed or semi-autonomous teams and percentage of employees with flexible work arrangements. These findings can also be supported by the process motivation model of Porter and Lawler (1968), who confirmed that employee satisfaction is determined by employee productivity, which could be improved through employee training. The more satisfied and productive employees are, the more they stay within the company, furthermore the requirement to higher satisfaction among customers.

In modern management theories, there is a variety of concepts concerning the attitude of employees and managers towards their company. These concepts serve as generator for motivation in terms of increasing performance and loyalty of employees towards the company as well as the involvement of the workforce in necessary project changes. Empowerment, targeting agreements, individual career planning are not only modern management issues and challenges, but also the most important need of young generation.

Hattie, Hodis, and Kang’s (2020) study on new theories of motivation with unique aspects and contributions, indicates four similar dimensions e.g., person factors comprising self (expectations, self-efficacy), social (modeling, comparisons), and cognitive aspects (self-regulation); task values; goals; and perceived costs and benefits. They describe motivation as a complex interplay of internal and external factors. A greater focus on individuals’ motivation profiles, construal of situations, and metacognitive monitoring and control of goal pursuit would give insight into the moment-by-moment decisions people make in daily life.

Graham’s model (2020) focuses on the attributions, or ‘why’ questions. She starts with an outcome (success, failure, happy, sad) and then the individual searches for reasons for this outcome. These reasons relate to ability, effort, or affiliation which lead to three causal dimensions: locus (within or outside the person), stability (enduring over time or not), and controllability (subject to volitional influence). It is called as an 8-cell explanation: 2 locus, 2 stability, and 2 controllability dimensions. How individuals react to the consequences of these causal ascriptions leads to a rich discussion about self-esteem, self-handicapping, and being a member of a stigmatized group. The value of this attribution model is that there are direct messages about attribution retraining with focus not only on the causal attributions, but also on the friendship networks and peer influences.

Schunk and DiBenedetto (2020) regard motivation as a function of agency, monitoring progress towards a goal, and the individual’s sense of perceived capabilities to learn and perform actions. Their model is very goal oriented hence the importance of expectations, anticipated outcomes, and the important distinction between mastery and coping models, but the main emphasis is on self-efficacy. Motivation is a function of the feedback learners receive as they work on a task, specifically as they make progress (or not). The belief that they are making progress substantiates their self-efficacy, which enhances motivational outcomes and motivation. In turn, increased self-efficacy promotes continued motivation and achievement.

In the business world, feedback may be received of employees’ chief, a leader in a position to direct the motivation of his employees. The relation between leader and employees, also as basis for organizational climate, supports job satisfaction of both parties catalysing their performance. Especially in crisis times the relations need support also with higher weight of human health, physically and psychologically. Leadership style has to be suitable for the constitution of the working teams in organizations. Known of analysis by James Mac Gregor Burns in the 1990s, transformational leadership is a concept of leadership with the objective to lead the values and attitudes of employees away from egoistic, individual goals. Superiors try to motivate their employees intrinsically, guide subordinates to long-term, overarching goals, for example conveying attractive visions communicating the common path to goal achievement (Reid and Dold, 2020). Superiors act as role models and supporting the individual development of employees. Within the literature, leadership is classified into four main categories: Transformational, Democratic, Authoritative, and Pacesetting. Transformational leadership traits include charisma, continuous and intense interaction between the leader and subordinates, defined short-term goals, coaching (motivation, inspiration) and a high level of integrity (morals and ethics).

Democratic leaders exhibit consultative traits, promote their vision (or mission), align skills and competences to roles in teams, enhance communication and aligns tasks to goals. Their deficit is flexibility to adapt to changing conditions.

Authoritative leaders’ dominance is control. Their traits include coercion, a task-oriented structure. Organisation may suffer poor communication and stifled growth and may not be suitable for organisations in a dynamically changing environment.

Pacesetting leaders are driven by innovation. Such leaders are at the forefront of start-ups but become less motivated after the successful launch of the product

The relation between leader and employees, the basis for organizational climate, supports job satisfaction of both parties catalysing their performance. Especially in crisis times, the relations need support also with higher weight of human health, physically and psychologically.

Transformational leadership furthermore influences employees’ creativity through psychological empowerment (Gumusluoglu and Ilsev, 2009). Tafelin, Armelius and Westerberg (2011) analysed transformational leadership and its influence on employee well-being. Their results contributed recognition about short-term and the long-term effects of transformational leaders on well-being mediated through the impact the leader has on the climate at work. Another leadership style, which is also incentive for job satisfaction, is lateral leadership, primarily based on the work of the organizational sociologist Stefan Kühl from Bielefeld University. Kühl cleared out that the concept of lateral leadership is based on the three pillars, e.g., understanding, trust and power. Any employee is always guided laterally, even if a hierarchy exists. Understanding, power and trust, influencing factors of lateral guidance, can claim to be fundamentally applicable in any management situation and could be used as incentive factors enforcing job satisfaction (Kühl, 2017).

Even if leaders strive to keep ‘status quo’, the development sooner or later brings new situations. The changes in the organizational structure, technological procedures, reengineering, and the like can be some of the most frequent examples. Considering organizations cope with various times in which work is executed as well as various places where it is executed. Thanks to ICT an employee can work at the client’s place, at home, in a means of transport or in a café. The leader must be ready for the situations and be able to forecast the changes that will have an impact on his workers, and in terms of telework, on his teleworkers. Considering that organisations are undergoing significant changes in which the teleworkers concerned do not participate in the way traditional workers do and experience on a daily basis, the manager must be aware that he/she is leading teleworkers in a way that can be compared to new recruits. The leader has to terminate his telework mode and start the preparation process for the teleworkers, while caring about teleworkers’ competence stability and social stability at workplace and organization maintaining a good cooperation to each other as well (Bajzíková et al., 2016).

Even if leaders strive to keep ‘status quo’, the development sooner or later brings new situations. The changes in the organizational structure, technological procedures, reengineering, and the like can be some of the most frequent examples. Considering organizations cope with various times in which work is executed as well as various places where it is executed. Thanks to ICT an employee can work at the client’s place, at home, in a means of transport or in a café. The leader must be ready for the situations and be able to forecast the changes that will have an impact on his workers, and in terms of telework, on his teleworkers. Considering that organizations undergo substantial changes, in which the teleworkers concerned do not take part in the way the traditional workers do and experience daily, the leader must realize that he leads the teleworkers who can be likened to new recruits. The leader has to terminate his telework mode and start the preparation process for the teleworkers, while caring about teleworkers’ competence stability and social stability at workplace and organization maintaining a good cooperation to each other as well (Bajzíková et al., 2016).

Ethical leadership is characterised by personal actions centralizing interpersonal relations to promote normatively the behavior of colleagues. In the short term, ethical leaders may increase employee morale and incentive for management and work. It can increase motivation at work and collaboration in organizations (Al Halbusi et al., 2020). In the long term, ethical leadership can prevent ethical issues. Leaders’ loyalty promotes organizations being more successful. Ethical leadership traits are characterised by leading by example, developing, respecting everyone equally, communicating openly, managing stress and communicating fairly and effectively (Dey et al., 2022).

Perception and attitudes towards business ethics among members of four generational groups, namely members of Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials and Generation Z, show that all give significant support for ethics in business, as considering ethics help to ensure good company reputation, increase trust in relations with stakeholders, ensure the increase in efficiency and efficacy of business, contribute employee growth and development as well as to lower the cost associated with omissions in the workplace. Supervisors’ behavior is considered as the most relevant factor influencing one’s ethical decision making among members of all generations, while members of Z generation consider formal rules and procedures, and performance assessment system less important than Baby boomers. Generation Z members consider job pressures less important for ethical decision making then members of other generations. Generation Z is more oriented to individual believes than organizational guidelines for ethical behavior. Creating ethical leaders and a positive ethical climate ensures ethical values and behaviors in organizations are indispensable (Klopotan, Aleksić, and Vinković, 2020)

Digital transformation of the last decade will leverage consumption of technology products and make work-from-home as best available alternative for suitable working arrangement in organization (Almeida et al., 2020). Digital leadership is based on involving and developing all employees in utilizing digital technology for supporting companies to achieve business growth (Saputra et al., 2020). Soon and Salamzadeh (2021) found that digital leadership influenced the effectiveness of virtual teams significantly. Digital leadership is a competency complex, which consists of six aspects: e-tech savvy, e-change, e-social, e-team, e-trust, and e-communication. From the six aspects of digital leadership, only two aspects (e-trust and e-communication) have a significant and positive relationship with the effectiveness of the virtual team. It indicates that digital leadership influenced virtual team effectiveness as a form of digital collaboration.

Relationship between employee motivation, employee job satisfaction and work performance

Employee performance is considered as employees’ contribution at work involving quality and quantity of output, presence at work, accommodative and helpful nature and timeliness of output (Shahzadi et al., 2014). Employee performance is influenced by motivation; if employees are motivated, they evolve more effort and their performance will improve (Azar and Shafighi, 2013). The study of Rozi and Sunarsi (2019) stated a strong correlation by 0,69 between motivation and employee performance. Grant et al. (2007) resumed those employees who know how their work has a meaningful, positive impact on others are not just happier than those who don’t, moreover they are more productive. Motivated employees are more oriented towards autonomy and freedom and are more self-driven availing developmental opportunities more correctly as compared to less motivated employees. Employee commitment with their work and jobs is higher if employees are motivated as compared to less motivated employees (Vansteenkiste, Lens and Deci, 2007). Study results of Melati, Moeins and Tukiran (2021) on motivation and employee commitment shows a significant positive relationship between work motivation and commitment to the organization with a correlation coefficient of 0.789; the strength of the relationship is strong. The amount of contribution of work motivation to commitment to organization is 62.2%.

Employees’ work performance mostly depends on different factors such organizational structure, job security, trainings, compensations, employee satisfaction and motivation appraisals and performance. Managers can increase the effectiveness of job administration among other employees in the organizations with having employee motivation as procedure (Vanek, 2017).

Employee motivation forced productivity, performance, and persistence (Mujeeb and Ahmad, 2011; Abdulkadir, Isac, and Dobrin, 2021; Adeyeye, 2021).

It is also concluded that intrinsic rewards have a significant positive relationship with employee performance and employee motivation (Shazadi et al., 2014).

Findings of Ezenwakwelu (2017) revealed that job design and autonomy are motivation factors for employee commitment. Responsibility and personal growth had a significant and positive influence on employee commitment. He concluded that high performance could be achieved by highly motivated people who are ready to use their discretionary effort. Organizations should provide the scenario within which high levels of motivation can be achieved by offering incentives and rewards, satisfying work, and opportunities for learning and growth.

On the other side, morality and productivity of employees is highly influenced by the effectiveness of performance of an organization and its reward management system (Yazıcı, 2008). To satisfy customers, firms do much effort but do not pay attention to satisfying employees. But the fact is that customers would not be satisfied until and unless employees are satisfied. If employees are satisfied, they will do more work therefore, ultimately customers will be satisfied.

Due to the outbreak of the Coronavirus, companies fulfill their corporate social responsibility in the face of a viral outbreak with implementing measures. The demand of working remotely, a workplace complying with social distancing, increased, and employees in home office are challenged to balance situations of distractions beside their work e.g., one’s child wanting attention, coordinating house work or going for a walk with the dog. Employees experienced the lack of commitment. Meetings and workshops are only virtual, and sometimes technical issues, specific technologies or features of video conferencing are to be trained and requires time they need for real work done. Compensating with leisure time or sport comes off badly and screen fatigue reduces their attention. The laptop screen replaces the face-to-face interaction. Team members cannot directly contact their colleagues and leaders while feeling disconnected, less creative or productive. Working remotely often results in a fusion of work and private life and causes difficulties to disengage at the end of the work day. According to Teng-Calleja (2020), organizational actions supporting employees to adapt to the COVID-19 crisis are flexible work arrangements, mental health and well-being programs, physical health and safety measures, financial support, provision of material resources, and communication of short and long term plans. Support for everyone, as help to set up an organized and quiet workplace, focuses on the benefits of virtual meetings and workshops e.g., real-time visualization, ensuring familiarity with the technology, communicating ground rules, providing fast support to solve unexpected technical issues, scheduling compact sessions, using breakout sessions, encourage video calls and socializing with colleagues and leaders to avoid a social disconnect and supporting employees to maintain work-life balance (Teng-Calleja et al., 2020).

Central interest for management is job satisfaction and loyalty as encouragement for achieving organizational goals (Sulíková and Strážovská, 2019). This statement is supported by Rahman, Fatema and Ali (2019) as they resumed that motivational and job satisfaction factors either intrinsic or extrinsic must exist for productivity. Job satisfaction significantly impacts the performance of individual, interpersonal relationships in the workplace and absenteeism and fluctuations in the organization. Employees, who are satisfied with their work, have a positive job attitude, perform better, which again positively influences their satisfaction, have higher loyalty and also job involvement.

Sirota Consulting (2005) has been studying the attitudes of people at work and the business consequences of those attitudes for more than three decades surveying approximately 2.5 million employees in 237 private, public, and not-for-profit client organizations in 89 countries. They found by ‘’Three Factor Theory’’ that as more satisfied needs are added, as optimum adding combined equity, achievement, and camaraderie, the proportion of very satisfied employees increases exponentially, by 45%.

The research results of Shantini, Ferdinandus and Suparti (2021) showed a significant influence of motivation on employee performance, and a significant effect of leadership and work environment on employee performance. While motivation was the most dominant factor affecting employee performance, job satisfaction plays the most important role in terms of evolving employees’ motivation.

Job satisfaction significantly impacts the performance of an individual, interpersonal relationships in the workplace and absenteeism and fluctuations in the organization. Employees, who are satisfied with their work, have a positive job attitude, perform better, which again positively influences their satisfaction. Covid-19 required many changes, which the organization and employees had to face equally. In order not to reduce productivity, managers had to find new approaches to keep their subordinates motivated; they had to focus on maintaining their level of job satisfaction or find ways to increase it. The key issue here was the leadership style of the people with an emphasis on an individual approach. Effective appropriate development Programs are one way how to increase managerial competences to enhance job satisfaction and motivation of employees and in the next step their productivity.

Methods

The research fundamentally bases on literature review. The method of qualitative content analysis by Mayring and Fenzl (2019), an essential part of the literature analysis, was a supportive element to interpret the findings. The coding system MAXQDA developed by Kuckartz (2019; 2020) has been applied for achieving a structured analysis. Scientific methods as synthesis, deduction and comparations were elements for the elaboration of the chosen topic intending to answer the following research question: ‘What are the basics of effective motivation of employees as a competitive advantage for organizations in times of COVID-19?’ Performing extensive literature review and a qualitative literature analysis following databases/library catalogues have been analysed: Springer Link, SCOPUS, Research Gate, Google Scholar, Google Search, Wiley Online Library, Forbes, Harvard Business Review. Quantitative and qualitative data from scientific studies with cross-sectional, meta-analysis and longitudinal character have been collected and analysed. The main profession analysing field is Human Resource Management. Data included descriptive statistics and have been deductively analysed. Thereby, tables, graphs and charts with nominal, ordinal and metric data of interviews and surveys have been collected and analysed. Elaboration of theoretical basics targeted on selected problems has been required for achieving the goals. All sources corresponding to the valid scientific requirement for the level of detail and quality of the elaboration have been classified as relevant. The literature research identified 90 potential sources, 79 were identified as relevant and attached as references. Relevant data were collected, categorised and analysed. Applying MAXQDA one main code, reflecting the subject ‘’Motivation’’, has created two ‘’first-level subcodes’’. Two ‘’second-level subcodes’’ have contributed to the topics, first ‘’History of Motivation’’ targeting an outlook for the history of theories and second ‘’motivation and employee motivation’’, which lead to 5 second level subcodes reflecting by the upper term the importance of the research field motivation, its influences and fields of action within the labour market. Five ‘’third-level-subcodes’’ have been emerged inductively and deductively. The present literature has been encoded by the method of structured content analysis. Thereby, passages have been encoded in 642 codings and subsequently analysed in relation to the research question. Synthesising all data, led to the following results and conclusion. Frequent individual studies and research reflecting similar results could lead to an inductive relation with possible recommendations for companies against their bias. Overview of the created codes and subcodes, as well as their hierarchy, see Figure 1.

Fig. 1: Hierarchical code-subcodes model by MAXQDA

Source: Authors’ own depiction

Discussion

Determinants of workplace and central motivating factor ‘’job satisfaction’’

Companies’ ability to maintain and gain market share and to be prepared for the future in a world suffering of a Pandemic, like COVID-19, is a new challenge. Managing internal and external environmental factors that allow employees to make the greatest possible contribution to company productivity and competitiveness is currently a greater issue for the companies to achieve. The impact of the Internet and technology accelerates in a higher rate compared to years before. Especially in terms of how and where we work in order sustain workforce by social distancing which is the current theme for companies to arrange. Work in teams converts to virtual teams under the time of COVID-19 Pandemic and companies have to balance the work schedule for their employees to stay satisfied, maintain their performance and that of their employer. Performance of employees is dependent on special factors. Research of Widarsih et al. (2018) revealed that organizational culture, personality and job satisfaction have a direct positive effect on performance, of which job satisfaction reflects a higher value measured of 0,367 correlation to job performance. It becomes clear that job-satisfaction increases with higher age and directly could be used as a catalyst for performance which is a basic contribution as subject of the research topic. Job satisfaction, according to Niemiec and Spence (2016), is a charming or fantastic passionate kingdom, as a result of the appraisal of one’s job or method studies. Boamah, Read and Spence Laschinger (2017) describe job satisfaction as a kind of committed factor which is related with business effectiveness. Judge et al. (2017) concludes, when employees are satisfied with their job, then it creates charming pressure within organization, motivates employees to job well and the organization can get excellent achievement from them. According to Bronner and Kaliski (2007), job satisfaction is a worker’s sense of achievement and success in the job. It is generally perceived to be directly linked to productivity as well as to personal well-being. Job satisfaction implies doing a job, one enjoys, doing it well and being rewarded for one’s efforts. Job satisfaction further implies enthusiasm and happiness with one’s work. Job satisfaction is the key ingredient that leads to recognition, income, promotion, and the achievement of other goals that lead to a feeling of fulfilment. Companies with high levels of employee satisfaction tend to have higher profitability and productivity, a rule investigated by the science of management. Companies are very interested in fostering employees’ job environment to develop job satisfaction of their workforce with a target on increasing productivity. Achieving the best results by coaching work teams, there are many pieces of research done about the field of job satisfaction, workforce and the ageing workforce. Job satisfaction is the result of effect of so many motivational factors. The terms are highly personalized, as the level of satisfaction differs from time to time and situation. Diamantidis and Chatzoglou (2018) examined the interrelations between firm/environment-related factors (training culture, management support, environ-mental dynamism and organizational climate), job-related factors (job environment, job autonomy, job communication) and employee-related factors (intrinsic motivation, skill flexibility, skill level, proactivity, adaptability, commitment) and their impact on employee performance and resulted that adaptability and intrinsic motivation have only a direct impact on performance. At the same time, job environment, management support and organizational climate have a considerable impact not only on employee performance but on the other factors as well, e.g., management support has an impact as well on job environment, organizational climate. Organizational climate creating job environment has an impact on job performance, while job environment has an impact on intrinsic motivation, proactivity and adaptability. Organizations often consider four factors as extrinsic motivation determinants, e.g., salary, monetary incentives, financial facility and compensation package. Rahman, Fatema and Ali (2019) cleared out that intrinsic and extrinsic factors of motivation and job satisfaction have an impact on the performance of workers. Motivational and job satisfying factors together can accelerate the performance efficiency of the organizations. The above-described research results declare that the inclusion of intrinsic or extrinsic factor will improve performance. The absence of intrinsic or extrinsic factors of job satisfaction will create dissatisfaction of workers. If any factor remains absent either intrinsic or extrinsic, then the organization will experience less productivity. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors of performance have to exist ensuring productivity. Different statistical findings indicate that mere motivation or job satisfaction fails to achieve productivity. It indicates that mere intrinsic or extrinsic factors cannot achieve performance. Essentially, motivational and job satisfaction factors either intrinsic or extrinsic must exist for productivity. Psychology, research field of the study of organizational behavior, is interested in analyzing the significance of positive organizational behavior for enhancing desired work-related outcomes, while job satisfaction is a central issue. While companies are aiming to stay competitive on market, they are forced to develope strategies to be successful. Strategies in teaching and leading by stimulus using methods encouraging persistence in a behavior are potentials for achieving goals (Woolfolk, 2010). Organizations and especially companies would profit by latently developing successful strategies to provide their employees with desired stimulus after behavior leading to an incentive to stay satisfied in job and wish to contribute with their performance. A large study of the American workforce indicates that workplace effectiveness (i.e., workplace flexibility, management decision-making involvement, positive co-worker support, learning opportunities, supervisor support for success, and job autonomy) is related to the overall job satisfaction, engagement, and retention (Jacob et al., 2008). Various and mixed research studies with conclusions to the topic are performed. Telecommuting has both, positive and negative impact on job satisfaction (Bailey and Kurland, 2002). Some researchers found curve linear effects (Guimaraes and Dallow, 1999) and some inverted U shape linearity effects of the relationship between telecommuting and job satisfaction (Golden and Veiga, 2005). It implicates that up to a threshold of telework hours job satisfaction decreases, which can be a guideline for managers and employees themselves. According to the research of Gajendran and Harrison (2007), Charalampous et al. (2019) and Golden and Veiga (2005), an increase of telecommuting intensity in an adequate range could result in a growth of individual outcomes, like job satisfaction, performance and perceived carrier prospects. If the telecommuting intensity is not adequate, it tends to cause role stress or turnover intention. Secondarily, the quality and quantity of psychological mediators for instance perceived autonomy, relationship quality and work family conflict, better explained like work family relationship, are able to trigger the individual outcomes in an attenuated or strengthened mode. The relationship between telecommuting intensity, psychological mediators and individual outcomes is described by the results of the meta-analysis of Gajendran and Harrison (2007). They applied conceptual support for the role of perceived autonomy, work–family conflict and relationship quality, from former the model developed by Allen, Shore and Griffeth (2003).

The literature results originated by a structured synthesis of all included studies made up by the final sample of 34 studies involving 699529 probands from single studies and included two meta-analyzes. Only two of the overall research studies performed by Schall (2019) and Golden and Veiga (2005), analyzed teleworking and its influence only on one dimension, i.e., job satisfaction. All other investigations used more than one dimension affecting working individuals’ wellbeing i.e., categorized in affective, cognitive, social, professional, and psychosomatic. There was an international representation of countries, like the USA, Austria, Germany, Swiss and Belgium, where studies were conducted. The authors use various data-pools and have analyzed various dimensions with different variables and conditions in relation to teleworking within different times, respectively years.

Advantages and disadvantages applying telework

The idea of working from home with the help of information and communication technologies (ICTs) was promoted by California-based companies like Yahoo already in the 1980s under the term ‘’Telecommuting’’, also known as ‘’Telework’’, as a predecessor or an early form of work with New ICTs. Three generations of telework were defined, as first home office, second mobile office and third virtual office (Messenger, 2016). A characteristic of home office is using information communication technology, which is not capable of mobilizing, mobile office indicating smaller and lighter wireless devices and virtual office as accessibility anywhere at any time by using clouds and portable devices. According to the results of Fílardí, Castro and Zaníní (2020), advantages of teleworking are saving time, cost reduction, creation of standardized measurements, and the knowledge of the real demand of work. The main disadvantages identified were difficulty in communication and control of the teleworker, differences in the relationship between the traditional worker and the teleworker, workers who do not adapt, psychological issues, and the teleworker’s return to traditional work.

Ipsen et al. (2021) indicated that most people had a more positive rather than negative experience of working from home. Three factors represent the main advantages of home-office e.g., work–life balance, improved work efficiency and greater work control. The main disadvantages were home office constraints, work uncertainties and inadequate tools. Comparing gender, number of children at home, age and managers versus employees in relation to these factors provided insights into the differential impact of home-office on people’s lives. These factors help organisations understand where action is most needed to safeguard both performance and well-being.

Data of the overview report of the ‘’Fifth European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS)’’ published by Parent-Thirion et al. (2012), conducted in 2010 with a total number of 43,816 interviews across 34 European countries revealed as advantage that 21% of total teleworkers have the most autonomy in setting their working hours, determine their work schedules themselves, contrasting only 10% of all partial teleworkers and 3% of those who never telework. Flexible working hours within certain limits are reported by 34% of all partial teleworkers, 21% of all total teleworkers, but only by 13% of those who never telework. The combination of more working hours and more autonomy leads to highly ambiguous results for teleworkers’ reported balance between paid work and personal life. Around 35% of all teleworkers report that they can easily take time off for personal matters during regular working hours compared to 27% among those who never telework. As disadvantage, they perform paid work much more often in their “free time” to meet work demands. Around 42% of all total teleworkers, but only 20% of the non-teleworkers, do so at least once or twice a month. This share is even higher among partial teleworkers (54%). The results suggest that telework itself is the paid work that extends into personal life, alters perceived work-life balance and also has notable effects on the health of employees. Data show that among all teleworkers 33% are stressed most of the time or always, only 25% of the no telework group. The higher stress levels are problematic particularly for partial teleworkers. The share of teleworkers who suffer from health impairments such as insomnia, overall fatigue, headaches or eyestrain is significantly higher compared to the group of employees who do not telework. According to Messenger (2020), teleworkers, including home office workers, report advantage of reduction of commuting time, higher productivity, and more time spent with family and friends. Disadvantages are negative effects of investing of longer working hours and a blurring of the boundary between paid work and personal life could possibly be cushioned effectively with more appropriate managerial guidance, stricter separation between workplaces and the home, and clear working time regulations. After Messenger (2020), telework can improve work–life balance, job satisfaction and enhance individual performance, but generally requires a significant degree of autonomy. Telework and its influence on employees’ productivity and job satisfaction, which are interesting for employers and companies to stay productive and competitive on market, proved to be an option to keep employees occupied in jobs, especially under crisis situation.

Results

Relocation of workplace under Covid-10 Pandemic

According to Statista (2020) based on a survey by the Ifo Institute with 800 interviewed German HR managers, in the second quarter of 2020, 20 % of the German workforce managed from home before the Corona crisis.

As a result of the Pandemic, this distribution has increased by around 20 % to around 60 % (Hofmann, Piele and Piele, 2020). In the time of Corona Pandemic, 70 % of the respondents stated that their office workers almost completely or mostly work in the home office, 21 % following the model of a 50:50 office work mixed with home office.

Blom et al. revealed that the majority of those in employment continue to work in office to the same extent as before. This value changes in a weekly comparison between 53% and 56 % of a sample size of 3,600 employees. Around a quarter of the employed workers are in the home office, compared to pre-Corona times with around 12% of all employed people in Germany (Blom et al. 2020).

Results of a representative survey on behalf of the Bitkom digital association from 11-15 March 2020 of more than 1000 German citizens aged over 16 revealed that 49 % employed respondents now work entirely or at least partially in the home office (Markert, 2019).

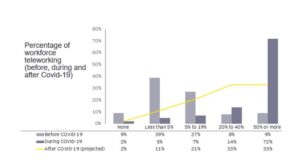

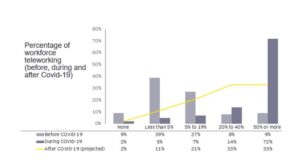

Hausser et al. (2020) evaluated statistical data in the USA pre and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The outcomes of the teleworking trends before, during and after COVID-19 results accorded to observations of which 24% of responders employing fewer than 500 employees and 76% more than 500 employees. Businesses that had 20% to 40% of their workforce teleworking before COVID-19 experienced a slight increase during COVID-19 but plan to significantly increase the teleworker population after COVID-19. Businesses that had 50% or more of their workforce teleworking before COVID-19 had a significant increase during COVID-19, will scale back telework to somewhat after COVID-19, but will still have significantly more teleworkers after COVID-19 than they had before the crisis (Hausser et al. 2020), as displayed in figure 2.

Fig 2. Teleworker trends before, during and after COVID-19 polling results USA

Source: Hausser et al. (2020), Copyright 2022, Ernst & Young LLP, All rights reserved

The proportion of teleworkers before pandemic (in 2015), according to Eurofound, was on average 19,8 % in European countries, Romania with 10%, Slovak Republic 12% and Denmark 38% (Ahrendt and Mascherini, 2020). As a result of the pandemic, 20% more workers started teleworking in April 2020, according to Eurofound. Romania with 19%, Slovak Republic 30%, Denmark 48% and Finland 58% and in general the largest proportions of respondents who switched working from home are to be found in Nordic and Benelux countries (Ahrendt and Mascherini, 2020). The results are significant to affirm that the scope of telecommuting has been increasing since the beginning of COVID-19 crisis. For European countries as well as for USA teleworking quantitative trends are similar been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Relationship between telework scope and job satisfaction

Organizational performance derived from individual attributes, work effort and organizational support (Rudy, 2021; Rudy et al., 2013). Individual attributes are characterized by gender, age, aptitude (capacity to learn something), ability (capacity to perform various tasks needed for a given job), personality, value, attitude and perception. While attitudes are influenced by values, they focus on specific people or objects, while values have a general focus. An important work-related attitude is job satisfaction, which is defined as the degree to which individuals feel positively or negatively about their jobs. Two closely related attitudes to job satisfaction are organizational commitment, as the degree to which a person strongly identifies with and feels a part of the organization, and job involvement, as the willingness of a person to work hard and apply effort beyond normal job expectations. Job satisfaction significantly impacts the performance, interpersonal relationships in the workplace, absenteeism and fluctuations in the organization, positive job attitude, which again positively influences job satisfaction. Companies’ quality of work environment is characterized by satisfaction on employee’s retention, satisfaction on performance. These relations and impacts are positively related to enterprise results (Rudy et al. 2013). It is a challenge for leaders improving employees’ performance evolving individual incentives to evaluate internal motivation which an employee derives from job satisfaction and further enhance it with external motivation as required (Varma, 2017).

Telework and its influence on workers’ job satisfaction and in general well-being has been extensively analysed and discussed. Job satisfaction has received the most empirical attention. Some conditions related to teleworking could trigger an increase or decrease of job satisfaction.

The comprehensive meta-analysis of Charalampous et al. (2019) gives a detailed insight to this working field and the dependent variables. Teleworking is responsible for workers’ positive emotions, for increasing their job satisfaction and organizational commitment levels and for ameliorating feelings of emotional exhaustion. As a result of this work style teleworkers feel more autonomous. Exclusively social isolation could be the reason for a drawback of teleworking.

According to Golden and Veiga (2005), the relationship between the extent of telecommuting and job satisfaction is curvilinear, and satisfaction and amount of telecommuting are positively related at lower levels of telecommuting and satisfaction plateaus resulted from higher levels of telecommuting with around 15.1 hours per week. This curvilinear relationship is moderated by several variables and the curve flattens with jobs higher in discretion and interdependence and for individuals higher in performance-outcome orientation. In terms of personality, teleworkers with a greater tendency to order and a higher need for autonomy report greater job satisfaction than do teleworkers with lower needs for order and autonomy.

Considering the development of scope applying teleworking in companies, it is conspicuous that teleworking in German companies raised from 22% to 39% from 2014 to 2018 (Statista, 2019). Employees statistically have experience with telework, both in general and in its extensive form due to the COVID-19 crisis.

The Ifo Institute reported 20%-increase of teleworking scope under COVID-19.

Beart et al. (2020) resumed that 65.9% of Flemish workers are completely satisfied with the increase of extended teleworking within the Corona Pandemic. 85% foresee the COVID-19 crisis as making teleworking and 81% of them foresee digital conferencing much more common in the future.

Golden and Veiga (2005) revealed a special termination of teleworking to receive beneficial job satisfaction. Specifically, low job satisfaction might cause extent of telecommuting; individuals might telecommute more extensively in order to improve their job satisfaction (Golden and Veiga, 2005), as valuable for practitioners and researchers. Life conditions abruptly changed in 2020 and teleworking became a need preventing serious infection. The worldwide population is obliged to train and always comply to keep distance from others, called ‘’social distancing’’ as long as the virus is not contained. Office jobs have to be restructured and teleworking could be the easier way to be arranged by companies and employees. We can assume that workers’ and companies’ attitude towards teleworking modifies to an obligatory workplace also for the next time. The situation cannot be assessed for the future. The research within Corona Pandemic, worth mentioning the work of Beart et al. (2020), analysed the number of employees which are satisfied with extended teleworking within the crisis. An evaluation towards a precise extension of telework in relation to the effects on job satisfaction and productivity in this research lacks in contrast to Golden and Veiga (2005). In case of persistent pandemic, it is relevant to analyse workers’ attitude towards teleworking in precise manner in order to cope with the crisis.

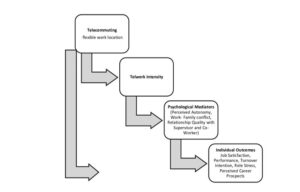

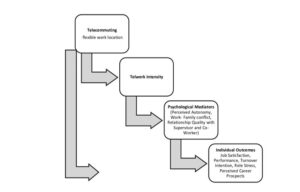

Based on Gajendran and Harrison (2007), the quality and quantity of psychological mediators such as perceived autonomy, relationship quality and work family conflict (better explained as work family relationship) are able to trigger the individual outcomes in an attenuated or strengthened mode. The theoretical relationship between the sections (figure 3) serves as a framework of the meta-analysis of Gajendran and Harrison (2007). They applied conceptual support for the role of perceived autonomy, work–family conflict and relationship quality, based on former models developed by Allen, Shore and Griffeth (2003) and Feldman and Gainey (1997). The individual outcomes of telecommuting are also derived from previous treatments of the consequences of telecommuting (Allen, Renn and Griffeth, 2003).

Fig 3. Theoretical framework for the consequences of telecommuting

Source: Authors’ own depiction based on Gajendran and Harrison (2007)

Life conditions abruptly changed in 2020 and teleworking became a need preventing serious infection. Office jobs have to be restructured and teleworking could be the easier way to be arranged by companies and employees. The research within Corona Pandemic, most worth mentioning is the work of Beart et al. (2020), analysed the number of employees which are satisfied with extended teleworking within the crisis. An evaluation towards a precise extension of telework in relation to the effects on job satisfaction and productivity in this research lacks in contrast to Golden and Veiga (2005). In case of persistent pandemic, it is relevant to analyse workers’ attitude towards teleworking in precise manner in order to cope with the crisis.

In fact, companies have to implement hygiene rules at workplace and arrange a new working structure for the future. Research of 2020, focusing on workplace in times of COVID-19 and its relation to job satisfaction, cannot give precise results since the current challenge faced by companies has only existed for several months. The OECD report (OECD, 2020) summarized the following coherences, which could help give a guideline for companies and provide researchers with new ideas for studies:

- Widespread teleworking may remain a permanent feature of the future working environment, catalyzed by the experiences made with teleworking during the COVID-19

- The use of teleworking before the crisis varied substantially across countries, sectors, occupations and firms, which suggests a large scope for policies to contribute to the spread of teleworking.

- While more widespread teleworking, in the longer-run, has the potential to improve productivity and a range of other economic and social indicators (worker well-being, gender equality, regional inequalities, housing, emissions), its overall impact is ambiguous and carries risks especially for innovation and workers.

- To minimize the risks of more widespread teleworking, harming long-term innovation and decreasing workers’ well-being, policy makers should assure that teleworking remains a choice and is not ‘overdone’. Co-operation among social partners may be the key to address concerns, e.g., of ‘hidden overtime’.

- To improve the gains from more widespread teleworking for productivity and innovation, policy makers can promote the diffusion of managerial best practices, self-management and ICT skills, investments in home offices, and fast and reliable broadband across the country.

These correlations, summarized by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development), are worth mentioning and lead to a new research ground. Connecting previous research results with analysed new conditions generated by the crisis of Coronavirus Pandemic will open new niches for researchers and companies.

Changing leadership by COVID-19

Leader should be ethical, have integrity, rely on considerable input from subordinates, and should enhance employee welfare.

Post COVID-19 leadership is responsible to enhance supporting components including a review of the organisational structure, a skills audit and defining new skills and competences, infrastructure assessment and acquisition of new technologies, and a renewed internal business environment and culture. The leader should be able to focus on the fears and needs of their subordinates, lead by example and participate actively in the process, identify sources of finance, lead negotiations and make strategic deals, identify and solicit new collaborative relationships, promote best skills and competences for the task, consider innovative ideas that are quick to implement, foster confidence and a self-confidence (can do) attitude in employees, motivate within the workplace, establish clear communication and implementation of prompt decisions (Ako Nai, 2020).

Results of Stoker, Garretsen and Lammers (2021) investigate the effect of home office during the COVID-19 crisis on changes in leadership behaviors, and identified changes in perceived manager quality and productivity, at different hierarchical levels in organizations. Summarising the views of the literature, applying home office in organizations could encourage managers to use less command and control and rather more delegation.. But research into the effects of exogenous shocks such as COVID-19, suggests that managers may become more controlling and delegate less. Their study on 748 responses (316 men, 431 women, and 1 other) with mean age of 47.4 years found consistent results with the first prediction. Managers perceive they execute significantly less control and delegate more. Employees also perceive a significant decrease in control, and perceive on average no change in delegation. Results are also in line with the second prediction that employees of lower-level managers even report a significant decrease in delegation. Increased delegation is associated with increased perceived productivity and higher manager quality. These results suggest the effectiveness of home office might be negatively influenced by the fact that required changes in leadership behaviors, in particular in delegation, are difficult to realize in times of crisis.

Liang (2021) identified needed attributes of leadership caused by Covid-19. Leadership led employees and team sustainably by carrying out various activities, making improvements, and also focusing on nonwork-related issues, motivating staff while addressing their fears and concerns regarding their job security, downsizing and salary cuts. Leadership became more humane by inquiring the personnel about their feelings and health statuses and more transparency by paying more attention to improve the productivity and performance of the team. Personnel small talks before meeting leaders keeping employees in good mood. While working from home a guiding role has been played by the leadership and more flexibility was offered to the teams/employees. The leadership was focused towards creating team spirit and unity while giving more freedom and flexibility to the team members in providing attributes as adaptability, flexibility, empathy, and candour and attributes of democratic leadership and situational leadership style e.g., applying active listening, coaching, managing remotely, correct communication, giving clear directions, and cooperation while working remotely.

According to Agarwal et al. (2020), effective leadership, respectively best practices in terms of COVID-19 are:

- Communicate regularly with team members in mutually agreed upon medium(s);

- Clarify roles and processes to perform tasks;

- Properly train employees on using the preferred communications platform (i.e., Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Hangouts, WebEx, etc.);

- Set speaking guidelines on the communications’ platform being used so people are not talking over one another and everybody gets to voice their opinions;

- Create clear meeting agendas that are attainable by everyone prior to the meeting;

- Schedule routine team and 1:1 meetings to stay in alignment with team members;

- Foster collaboration and encourage everyone to participate in meetings;

- Have frequent informal check-ins via chat or call to discuss project status and/or barriers;

- Be creative when coming up with ways to continue team building and maintaining relationships i.e., virtual happy hours, birthday celebrations, and online games;

- Track employee capacity before assigning new work to reduce stress;

Evaluate the pandemic’s influences on people’s lives by considering their motivation, social, health and mental conditions will be important for sustaining their success, in their private lives as well as in their professional ones;

Amid Covid-19 crisis, organizations need leaders who see the positive impact of digital technologies on business management, feel what is possible, what is important, what will be possible, what is right and what is not right. Leaders are looking for standardization and automation of processes to create new knowledge that they can use in differentiated functions. Digital ethical leaders should be able to adapt to constant change and not lag. They should learn every day and show leadership. Anticipating change should be their strength, for which they need to acquire a certain set of skills. Managers should identify and develop new digital skills. The most important thing is to better anticipate and respond to the competitive environment, to approach solutions comprehensively, to use data and analyzes to guide their decision-making. Leadership on an aspect of trust and cooperation with other employees, while trust is the foundation of leadership in digital transformation (Horná and Kmec, 2020), is the goal a leader has to accomplish in the future.

Conclusion

Emphasizing that employees are the company’s greatest asset while organizations think of ways to maximize their return on their investment, the quality of managers creates the ground to target this aim. Including the ability to work with others and get things done through people, effective managers’ ability is to motivate those they work with to behave in a specific, goal-directed way. As motivation is defined as energizing, directing and sustaining employee efforts, effort is one substantial factor beside ability and situation within the function of performance. While ability is applied in terms of the intellectual (using intelligence and reason to solve problems), the social (being personable and outgoing) and the mechanical capability (possessing the technical skills to do one’s own job), the situation is addressed to the work environment, job design and specific task assignments, which can have a strong influence on success. Employees’ ability and working in a comfortable environment support employees’ performance, while effort, the willingness to work hard, a worker’s or manager’s maximum asserting, trigger their motivation to perform. Influencing basics to motivate employees at work, according to Zhang, Crant and Weng (2019), can be seen in one’s personality and one’s demand on proportion of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, people receive at work following their actions.

A key element of each employee’s personality is their level of intrinsic motivation which determines the level of job satisfaction, Zhang, Crant and Weng (2019) noted.

Covid-19 Pandemic disclosed unpredictable lacks of the whole worlds’ administrations, governments, health systems and business organizations. Reflecting the needs of organizations to sustain in market, organizations steadily maintain to restructure workplace, applying more advanced technology to recruitment, selection and performance (Przytuła et al., 2020). More interests, appreciation and motivation from managers will be needed as well as trust and a sense of belonging among team members with emphasis on enhancing physical, mental health and well-being, especially motivation. Work related values became more important and essential in times of Pandemic. Health and wellness, respect and dignity got higher value because of threat of infection, followed by financial security. Further work-related values are not to be neglected, as recognition for competence and accomplishments, personal choice and freedom, involvement at work, pride in one’s work, lifestyle quality, self-development. Companies have to stay flexible and open to offer situation adapting work arrangements e.g., telecommuting, compressed workweeks, flexible working hours, job sharing and part time work in order to keep their employees flexible, open and prepared for changes. Work/life balance, diversity, inclusion and compensation will become more important in attracting and retaining talent due to COVID-19. New ways of working demand for ‘‘new skills’’ including technical capabilities and workplace behaviors must be learned and improved steadily. Managers need to make sure reskilling efforts do not fall by the wayside and prioritize communication and constant contact with their workforce (Gregory and Levine, 2020).

Considering that crisis exposes hidden deficits, especially related to strengths and weaknesses of leaders, the possibility to analyze, recognize and modify social interaction between leader and employee will be inaugurated. Three themes are important to be emphasized during and after the crisis e.g., 1) communication, keeping employees informed and updated, 2) clarity of vision and values and also keeping the organization on track and focused on the issues of the day, and 3) caring relationships, employees’ concerns should not be ignored (Leschke-Kahle, 2020).

Supporting work from home implemented in company policies and regulations would make employees feel safe, comfortable, and protected. Sharing information and maintaining effective communication between employees through technology e.g., by periodically video conferencing to compensate face-to-face meetings (Raghuram et al., 2019) could directly increase team spirit and cohesion (Kaul et al., 2017).

Providing safety equipment e.g., masks, disinfectants and healthy lifestyle e.g., food, focuses on the basic needs regarding Maslow’s theory. If the needs at a lower level have been satisfied, there will be needs at a higher level.

Self-efficacy affects employee performance. Improving employees’ work self-efficacy let increase the intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation of employees, while extrinsic motivation deals as a mediator of self-efficacy on employee performance. Intrinsic motivation includes challenges, aesthetic value, novelty, interest, and enjoyment as opposed to monetary rewards or external pressure, and is supported by autonomy and competence and could never be ignored satisfying employees with job (Honig, 2021). Lower levels of supportive practices are associated with greater desire to exit for employees with higher levels of intrinsic motivation.

In the pandemic of Covid-19, extrinsic motivation must be focused more because this motivation intensively causes employee performance. Manager can apply attractive incentive, bonus, commission programs, rewards employees and give recognition for good employee work to promote extrinsic motivation (Nilasari et al., 2021)

Effective motivating leaders must be able to lead themselves and compensate their own insecurities and emotions.

Effective employee motivation amid crisis requiring a specific approach puts increased management requirements for their ability to effectively lead people, to effectively motivate them. This requires, in particular, individual approach and development primarily emotional and cultural intelligence, the ability to become a part of a team not only their manager. The correct selected development programs for managers in organizations can help this.

Superiors should help employees to overcome the obstacles evolved applying home-office e.g., resolving and compensation collisions of private and working time. Communication between superior and employee has to be clear and focused on their individual problems. Creating properly individual training schedules is important for employees, also for managers offered by the firms. New approaches to learning, rewards, space use, and removing hierarchies and barriers, building team leadership on trust-based moral values and being an authentic leader who is an example to others, could be a very precious concept.

References

- Abdulkadir, E., Isac, N. and Dobrin, C. (2021), ’Volunteer’s engagement: Factors and methods to increase volunteer’s performance and productivity in NGOs during COVID-19 Pandemic (Scout Organizations as a model),’ Business Excellence and Management, 11 (2).

- Acatrinei, N. (2016) Work Motivation and Pro-Social Behavior in the Delivery of Public Service, Theoretical and Empirical Insights, net Theses 23, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Adeyeye, AV. (2021),’ Performance appraisal: A strategic tool for enhancing firms’ productivity and employees’ job performance,’ Hallmark University Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 3 (2).

- Agarwal, S., Ferdousi, S., John, M., Nalven, A. and Stahl, T. (2021), ’Effective Leadership in Virtual Teams during the COVID-19 Pandemic,’ Engineering and Technology Management Student Projects. 2298. [Online], [Retrieved November 1, 2021], https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/etm_studentprojects/2298

- Ahrendt, D. and Mascherini, M. (2020), ‘Living, working and COVID-19, COVID-19 series,’ Publica-

- tions Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. [Online], [Retrieved October 22, 2021], https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2020/living-working-and-covid-19

- Ako Nai, S. (2020), ’Leadership in a Post COVID-19 Era,’ Information Technology and Governance, 8 (29).

- Al Halbusi, H., Williams, KA., Ramayah, T., Aldieri, L., and Vinci, CP. (2020), ’Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: the moderating role of person organiza-tion fit,’ Personnel Review, 50 (1), 159-185.

- Allen, DG., Shore, LM. and Griffeth, RW. (2003), ’The Role of Perceived Organizational Support and Supporttive Human Resource Practices in the Turnover Process,’ Journal of Management, 29 (1), 99-118.

- Allen, DG., Renn, R. and Griffeth, RW. (2003), ‘The Impact of Telecommuting Design on Social Systems, Self-Regulation, and Role Boundaries,‘ Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 22, 125-163.

- Almeida, F., Santos, JD., and Monteiro, J. A. (2020), ’The Challenges and Opportunities in the Digitalization of Companies in a Post-COVID-19 World,’ IEEE Engineering Management Review, 48 (3), 97-103.

- Azar, M. and Shafaghi, AA. (2013), ’The Effect of Work Motivation on Employees,’ Job Performance,’ International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3 (9), 432-445.

- Bailey, DE. and Kurland, NB. (2002), ‘A Review of Telework Research: Findings, New Directions, and Lessons for the Study of Modern Work,’ Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23 (4), 383–400.

- Bajzíková, L., Sajgalikova, H. and Polakova, M., Wojcak, E. (2016), ‘How to Achieve Sustainable Efficiency with Teleworkers: Leadership Model in Telework’ 5th International Conference on Leadership, Technology, Innovation And Business Management 2015, ICLTIBM (2015), 10-12 December 2015, Istanbul, Turkey, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 229, 33 – 41.

- Baumeister, R. F. (2016), ’Toward a general theory of motivation: Problems, challenges, opportunities, and the big picture,’ Motivation and Emotion, 40 (1), 1–10.

- Beart, S. et al. (2020), ‘The COVID-19 Crisis and Telework: A Research Survey on Experiences, Expectations and Hopes,’Institute of Labor Economics Bonn Germany. [Online], [Retrieved September 5, 2020], http://ftp.iza.org/dp13229.pdf

- Blom, A. G. et al. (2020), ‘The Mannheim Corona Study: Focus report on the use and perception of home office in Germany during the Corona Lockdown, ’Mannheim Germany: University Mannheim. [Online], [Retrieved September 1, 2020], https://madoc.bib.uni-mannheim.de/55628/?rs=true&

- Boamah, SA., Read, A. and Spence Laschinger, HK. (2017), ’Factors influencing new graduate nurse burnout development, job satisfaction and patient care quality: a time‐lagged study,’ Journal of advanced nursing, 73 (5), 1182-1195.

- Bronner, M., and Kaliski, BS. (2007), ’New Opportunities–Implications and Recommendations for Business Education’s Role in Non-Traditional and Organizational Settings,’ Delta Pi Epsilon Journal, 49 (1), 32-37.

- Charalampous, M., Grant, CA., Tramontano, C., Michailidis, E. (2019), ’Systematically reviewing re-mote e-workers’well-being at work: a multidimensional approach,’ European Journal of Work and Or-ganizational Psychology, 28, 51–73.

- Chicu, D. (2015), ’Employees and customers in call centres: confirmatory and exploratory study,’ Universitat Rovira I Virgili. [Online], [Retrieved December 22, 2021], https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/396290/TESI.pdf?sequence=1

- Dey, M., Bhattacharjee, S., Mahmood, M., Uddin, Md and Biswas, S. (2022), ’Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role employee values, behavior and ethical climate,’ Journal of Cleaner Production, 337 (1), 130527.

- Diamantidis, AD. and Chatzoglou, P. (2018), ‘Factors affecting employee performance: an empirical approach, ‘International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68 (1), 171-193.

- Ezenwakwelu, C. (2017), ’Determinants of Employee Motivation for Organisational Commitment,’ IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 19, 1-9.

- Feldman, DC. and Gainey, TW. (1997), ’Patterns of telecommuting and their consequences: Framing the research agenda,’ Human Resource Management Review, 7 (4), 369-388. Fílardí, F., Castro, RMP., and Zaníní, MTF. (2020), ’Advantages and disadvantages of teleworking in Brazilian public administration: analysis of SERPRO and Federal Revenue experiences, ‘Cadernos EBAPE. BR, 18, 28-46. Gajendran, RS. and Harrison, DA. (2007), ’The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Metaanalysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1524–541.

- Golden, TD., Veiga, JF. (2005), ’The Impact of Extent of Telecommuting on Job Satisfaction: Resolving Inconsistent Findings,’ Journal of Management, 31, 301–318.

- Guimaraes, T. and Dallow, P. (1999), ’Empirically testing the benefits, problems, and success factors for telecommuting programmes,’ European Journal of Information Systems, 8 (1), 40-54.

- Gumusluoglu, L. and Ilsev, A. (2009), ’Transformational leadership, creativity, and organizational innovation,’ Journal of Business Research, 62 (4), 461–473.

- Graham, S. (2020),’An attributional theory of motivation, ’Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101861.

- Grant, AM., Campbell, EM., Chen, G., Cottone, K., Lapedis, D. and Lee, K. (2007), ’Impact and the art of motivation maintenance: The effects of contact with beneficiaries on persistence behavior,’ Or-ganizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103 (1), 53-67.

- Gregory, A. and Levine, D. (2020), ‘The future of work arrives early: How HR Leaders are leveraging the lessons of disruption,’ Oxford Economics. [Online], [Retrieved Juny 1, 2021],https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/recent-releases/The-future-of-work-arrives-early-How HR-leaders-are-leveraging-the-lessons-of-disruption

- Hattie, J., Hodis, FA. and Kang, SHK. (2020), ’Theories of motivation: Integration and ways forward,’ Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101865.

- Hausser, K., Salam, D., Lowery, K. and Berard, P. (2020), ’Ernst & Young LLP webcast polling