Introduction

Higher education institutions are essential for any country due to their relevant role in socio-economic development and in the training of human resources (Nawaz, Usman, Qamar, Nadeem & Usman, 2020). According to Granovetter (2018), higher education serves as a means for the production of individuals with academic and mental capacity who, in turn, will assist in the production of highly qualified labour for the various sectors of the economy. Subair and Talabi (2015) argue that the intellectual and professional life of a country depends on a solid higher education since the most qualified workers adapt more easily to technological changes and to the substitution of work for capital that is currently taking place at the global level. This way, countries with more qualified human resources are better prepared to absorb innovation and technological substitution (Ferreira & Carreira, 2019). It is consensual that having managers who care about workers and having a good social environment in companies promotes productivity. In the case of Portugal, where the reduced labour productivity is considered a chronic problem in the economy, human resource management plays a critical role (Ferreira & Carreira, 2019).

Organizational commitment has been the object of study by several researchers in recent years, encouraging organizations to seek human resources management strategies with the objective of increasing productivity through the satisfaction and involvement of individuals within the organization. According to Meyer and Allen (1997), organizational commitment is a psychological commitment between the employee and an organization that can assume three distinctive forms: (1) when attitudes and behaviours are adopted not because beliefs are shared, but simply to earn specific rewards; (2) when an individual accepts influence to establish or maintain a satisfactory relationship; (3) when the influence is accepted because the induced attitude identify itself with the individual’s own values. Oliveira and Honório (2020) refer to organizational commitment as the identification of the worker with the organization and the objectives associated with the needs to remain in the organization. These authors emphasize that the high level of organizational commitment raises the organizational standards of meeting goals and improves performance, insofar as it generates joint satisfaction between employer and employees. Hollenbeck and Jamieson (2015) also point out that human beings need to feel committed to something or someone to receive rewards, and that commitment reflects satisfaction, performance improvement, cost reduction, a better way to manage and stand out in the corporate sphere.

Thus, the aim of this work is to give visibility to the scientific results, which may be of great use to higher education organizations, as an instrument for decision-making in order to improve the organizational commitment of their employees and guarantee all the advantages that it entails, namely, better organizational performance, higher level of job satisfaction, improved productivity, promotion of the optimization of employees’ capabilities, creation of opportunities, development of individual and group skills of employees, reduction of absenteeism, among others. In addition, it can contribute to the scientific community, through the dissemination of lines of research to be explored within the scope of organizational commitment, contributing this work to minimize the scarcity of existing studies that involve all employees of higher education organizations and not only teachers, as is referred in the existing literature.

In this context, the starting question that the present research intends to answer is “what is the level of organizational commitment of employees?” The general objective of this work is to analyse the organizational commitment in a public higher education institution and the specific objective is to verify if there are differences in the organizational commitment of employees taking into account the type of employment contract.

Theoretical framework

In the current organizational context of globalization, technological and cultural advances, and pandemic crisis, the recruitment, selection, retention and reward of motivated employees, dedicated to the organization’s goals, are a fundamental factor in order to obtain competitive advantages. Therefore, the study of organizational commitment should be important to educational institutions, as they play a central role in the development and training of human resources (Rusu, 2011). If an organization wants to have successful and effective employees, they must be satisfied with all aspects of their work and, at the same time, feel committed to the organization (Jordan, Miglic, Todorovic, & Maric, 2017). Lima and Rowe (2020) and Ferreira and Carreira (2019) add that committed people feel more engaged and motivated to perform tasks at work, as the collaboration of workers in carrying out their work and achieving organizational goals is greater, decreasing turnover intention. Strong organizational commitment implies a link that promotes a positive behaviour or attitude towards an organization that predisposes the individual to behave in a way that benefits the organization (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001).

Allen and Meyer (1990) defined organizational commitment as an employee’s emotional attachment, connection and sense of belonging to the organization where they work (Meyer & Allen, 1991; Horta, Jung, Zhang, & Postiglione, 2019). Individuals with high organizational commitment protect organizational heritage, share organizational goals and remain with the organization through good and bad times (Batugal & Tindowen, 2019). According to the literature (Thomas, 2008; Batugal & Tindowen, 2019; Gouveia, 2019; Lima & Rowe, 2019; Nguyen, Nguyen, & Le, 2021), the most consensual and robust organizational commitment model was developed by Meyer and Allen (1991), and has received greater attention and application by the scientific community. This three-dimensional model incorporates three concepts, namely: (1) affective commitment, which refers to emotional attachment, in this sense, employees remain in the organization because they want to; (2) the calculative commitment, that is, employees remain in the organization out of necessity, due to the lack of alternatives or because the costs of leaving the organization are too high (for example, loss of income, loss of benefits, among others); and (3) normative commitment. According to these authors, in normative commitment, employees remain in the organization because they feel this obligation towards the organization, out of loyalty or because they believe that the organization has invested a lot in them and, therefore, they feel a duty to reciprocate. The three dimensions of the organizational commitment model are considered components and not different types of commitment, since the same individual can develop all three towards the organization (Gouveia, 2019).

From the 1980s onwards, flexible employment emerged and dominated. The use of temporary work in Portugal has become a resource increasingly used by organizations, which recognize in work flexibility the main driver of productive development and the only way to ensure its competitiveness and survival (Rebelo, 2006). The growth of unemployment and the flexibility of work organization models, according to Rebelo (2006), have marked, since then, the dynamics of the labour market. Despite being framed in current legislation, the use of this type of work does not always seem to be properly justified (Ferreira and Santos, 2013). Massive unemployment favours the use of flexible forms of employment, due to the availability of the workforce it generates and the ease of using people’s work needs, as they find themselves without a better choice. In this way, temporary work is often associated with precariousness, poor working conditions, great instability of income and difficulty in accessing social rights (Glaymann, 2008), which can sometimes lead to disrespect for labour standards. According to Paugam (2000), precariousness usually implies being poorly paid and little acknowledged, generating disinterest and a feeling of uselessness on the part of the employee. Temporary workers, in addition to earning lower wages and fewer benefits compared to workers with a bond to the organization do not, in most cases, receive training, nor are they offered the possibility of career progression, giving rise to feelings of insecurity regarding their professional future (Booth, 2002), demotivation and negative attitudes towards the organization (Ashford, George & Blatt, 2007), reasons why temporary workers exhibit less affective commitment to the organization. However, the literature on these aspects is not consensual since, according to Pearce (1993), there are no differences in the affective commitment of temporary workers, with a fixed-term contract, compared to permanent workers, with an open-ended or uncertain-term contract. Van Dyne and Ang (1998) concluded that workers with fixed-term contracts had lower levels of affective commitment than workers with open-ended contracts. However, taking into account the three dimensions of organizational commitment, Batista (2016) noted that workers with fixed-term contracts showed higher levels of calculative commitment, that is, they registered a greater involvement based on the desire for affiliation or for necessity. Workers with uncertain-term contracts, on the other hand, showed higher levels of affective and normative commitment, that is, they registered higher levels of involvement because they wish to do so or because they feel an obligation towards the organization.

Research Methodology

Type of study and hypotheses

The present research work is a quantitative, cross-sectional and observational study. The objectives were: (1) to determine the level of organizational commitment of employees of a public higher education institution, located in the Northeast of Portugal; and (2) to verify if the level of commitment is the same for all the institution’s employees, regardless of the type of employment contract. In this context, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H0: The level of organizational commitment is the same for temporary workers, with a fixed-term contract, and permanent workers, with an uncertain-term contract.

against

H1: Temporary workers, with a fixed-term contract, exhibit different levels of commitment when compared to permanent workers, with an uncertain-term contract.

As already mentioned, the sample used for this study considers the employees of a public higher education institution from Trás-os-Montes region, located in the Northeast of Portugal. This is a probabilistic sample insofar as the probability of a given individual belonging to the sample was the same for all employees. The sample involved 105 employees out of a total of 783. Therefore, the response rate was 13.41% and the sampling error, for a confidence level of 95%, was 8.9%.

Data Collection Instrument

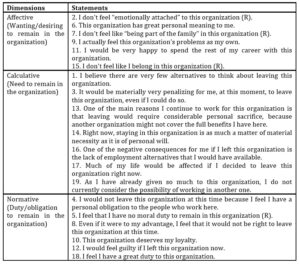

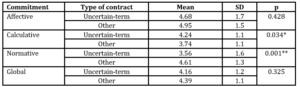

For data collection, which took place from October 22, 2021 to January 4, 2022, a questionnaire prepared with the help of the Google Docs tool was sent, via institutional email, to all the organizations’ employees. The questionnaire comprises two sections. The first section includes questions related to the respondent’s demographic and professional situation (gender, age, workplace, professional category, functions performed, length of service, length of service in the same professional category, type of employment contract). The second section included the commitment scale developed by Meyer and Allen (1991) validated and adapted to the Portuguese context by Nascimento, Lopes and Salgueiro (2008). This scale consists of 19 statements evaluated in a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Subsequently, these 19 items originated three subscales or dimensions: (1) affective commitment; (2) calculative commitment or continuance commitment; and (3) normative commitment. In this way, organizational commitment is analysed under three fundamental dimensions: affective, calculative and normative (Lizote & Morais, 2021). These authors propose six items for the affective commitment scale (items 2, 6, 7, 9, 11 and 15), seven items for the calculative commitment scale (items 1, 3, 13, 14, 16, 17 and 19) and six items for the normative commitment scale (items 4, 5, 8, 10, 12 and 18), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of Organizational Commitment

R – Statements formulated inversely in order to facilitate the interpretation.

Pinho and Bastos (2014) and Pinho and Oliveira (2017) state that the multidimensional model by Meyer and Allen (1991) has gained high popularity among researchers and, over time, has received important empirical support; reasons that justify its dominance in the field of organizational commitment, especially from the 1990s onwards. In fact, this is the reason why this model was adopted in the present research. Therefore, in the referred model, permanence in the organization may come from desire, need and a sense of duty or obligation (Table 1).

Editing and data processing

Data were edited and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 26.0. The significance level used in this study was 5%. Descriptive statistics were calculated, namely absolute and relative frequencies; measures of central tendency (mean, median and mode) and measures of dispersion (standard deviation, maximum and minimum) (Pestana & Gageiro, 2014; Marôco, 2018).

Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was applied to analyse the reliability of the questionnaire and the internal consistency of the responses. The value must be positive, ranging from 0 to 1; values greater than 0.9 mean that the consistency is very good; between 0.8 and 0.9 mean it is good; between 0.7 and 0.8 correspond to reasonable; between 0.6 and 0.7 to weak; and values below 0.6 are not admissible (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Additionally, Levene and Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) homogeneity and normality tests were used, respectively, to verify the necessary assumptions, for the use of Student’s t test for two independent samples (parametric test). The t-Student test allows testing the null hypothesis of equality of means (H0: µ1 = µ2) against the alternative hypothesis of the means being different (H1: µ1 ≠ µ2), wherein µ is the mean and the 1 and 2 represent the type of employment contract, namely, uncertain-term contract and other.

Finally, the Pearson correlation test was used to measure the strength of the correlation between the several dimensions of the organizational commitment model. This test allows calculating the “r” correlation coefficient that varies between -1 (perfect negative or perfect inverse correlation) and 1 (perfect direct or perfect positive correlation). Values close to zero indicate a weak correlation and values close to 1 indicate a strong correlation. Therefore, when the correlation coefficient varies between 0.7 and 0.9, positive or negative, the correlation is strong; if it varies between 0.5 and 0.7, positive or negative, the correlation is moderate; if it varies between 0.3 to 0.5, positive or negative, the correlation is weak, and, if it varies between 0 and 0.3 positive or negative, the correlation is considered negligible (Pestana & Gageiro, 2014).

Ethical Issues

In this research, data collection began after a positive response obtained to the written and formal request made to the head of the Public Higher Education Institution. Data collection started with a positive opinion from the Ethics Committee of the same institution.

When invited to participate in the study, employees were informed about the objectives and scope of the study and that the data collected would be treated anonymously, guaranteeing confidentiality. Additionally, employees were informed that the dissemination of results, in the academic and scientific media, would be done in an aggregated and anonymous way. The employees who integrated the sample did so voluntarily, after their informed consent.

Results and Discussion

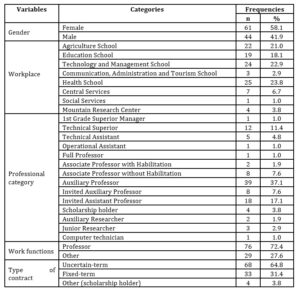

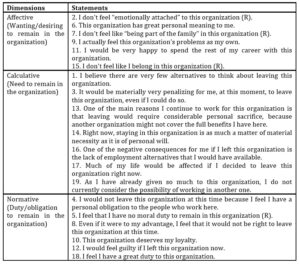

As previously mentioned, a random sample of 105 employees was obtained. Of these, 58.1% were female and 41.9% were male. In terms of professional category, the three most representative, with more than 10% of the answers, were: Auxiliary Professors (37.1%), Invited Assistant Professors (17.1%) and Technical Superiors (11.4%). Taking into account the type of work function, the overwhelming majority were teachers (72.4%) from Health School (23.8%), Technology and Management School (22.9%), Agriculture School (21.0%) and Education School (18.1%). Finally, regarding the type of employment contract, it can be seen that the majority have an employment contract for an indefinite period or uncertain-term contract (64.8%), considered as the usual type of contract, since the fixed-term contract is celebrated by the organization in order to satisfy the organization’s temporary needs for a period strictly necessary (Table 2).

Table 2: Sociodemographic and professional characterization of workers (N = 105)

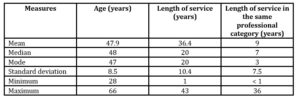

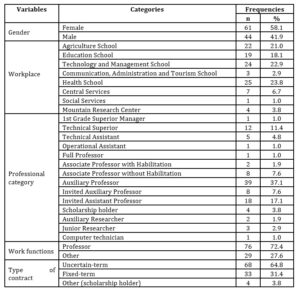

Table 3 shows that employees are aged between 28 and 66 years old, with an average age of 47.9 (SD = 8.5). As for the length of service, by professional category, the average was 9 years (SD = 7.5). Globally, the average length of service exceeds 36 years, however, the length of service varies from 1 to 43 years.

Table 3: Measures of central tendency and dispersion of age and length of service

In order to study the correlation between organizational commitment and its dimensions, Pearson’s correlation test was used. From the results obtained, it can be concluded that the three dimensions of organizational commitment are positively correlated to each other, as well as to global organizational commitment (Table 4). Furthermore, affective commitment (r = 0.867; p = 0.000 < 0.05) and normative commitment (r = 0.880; p = 0.000 < 0.05) present strong correlations with global commitment, while the correlation between the calculative commitment and the global commitment is moderate (r = 0.597; p = 0.000 < 0.05), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Pearson (r) correlations between the dimensions of organizational commitment (N = 105)

* significant at 0.05

** significant at 0.01

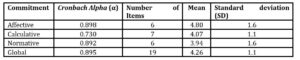

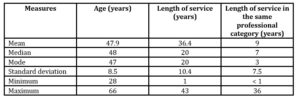

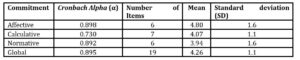

Table 5 shows the organizational commitment dimensions’ consistency levels. From the analysis of the values obtained, it can be observed that the lowest value of internal consistency is recorded in the subscale of calculative commitment (Cronbach Alpha = 0.730). However, all values obtained reflect good results of internal consistency of the scales used (> 0.7) (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). According to Batugal and Tindowen (2019), commitment is high when the average varies from 4.61 to 5.81.

Table 5: Cronbach’s Alpha, Number of Items per Scale, Mean and Standard Deviation by Commitment Type

In the final version of the Meyer and Allen (1991) scale adapted to the Portuguese context by Nascimento, Lopes and Salgueiro (2008), the internal consistency proved to be good (Pestana & Gageiro, 2014; Marôco, 2018; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). In fact, Cronbach’s Alpha values of 0.898, 0.730 and 0.892 were obtained for the affective, calculative and normative commitment scales, respectively (Nascimento, Lopes & Salgueiro, 2008).

Taking into account the levels of organizational commitment, Table 5 shows that respondents have higher levels of affective commitment (Mean = 4.80; SD = 1.6) and lower levels of normative commitment (Mean = 3.94; SD = 1.6). In the opinion of Anugrah and Priyambodo (2021), individuals who have higher levels of affective commitment will tend to have an emotional attachment towards the organization. Individuals feel the desire to remain in the organization. Affective commitment is associated not only with belief and trust in organizational values and goals, but also with the willingness to invest extra effort on behalf of the institution (Khasawneh, Omari & Abu-Tineh, 2012). Employees emotionally attached to organizations work longer hours, are more creative and perform their tasks more efficiently (Nawaz, Usman, Qamar, Nadeem & Usman, 2020). In the literature, affective commitment is favourable to employees and organizational results in terms of satisfaction, well-being, turnover and greater productivity. In fact, Meyer and Allen, (1997) and Lizote, Verdinelli and Nascimento (2017) showed that commitment in the affective dimension significantly relates to job satisfaction. However, the study developed by Ferreira and Carreira (2019) that involved higher education student workers in Portugal showed that greater affective organizational commitment of student workers implied a lower intention to leave the organization.

Regarding normative commitment, feeling experienced by employees in relation to obligations towards the organization, individuals feel a duty to remain in the organization. As it registered the lowest level, although moderate, it may mean that individuals remain in the organization for other reasons and not merely because of the obligation to perform their duties. Normative commitment appears to be positively associated with organizational outcomes, to a much smaller extent compared to affective commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1997). However, the normative dimension is negatively related to job satisfaction, indicating that the most normatively committed employees are the least satisfied (Lizote, Verdinelli & Nascimento, 2017).

Regarding the calculative commitment, the respondents registered a moderate level (Mean = 4.07; SD = 1.1). Probably, the necessity, the absence of alternatives, or the notion of high sacrifices in the exit, makes the individuals feel that they have to remain in the organization.

In general, the respondents’ global commitment to the organization was moderate (Mean = 4.26; SD = 1.1). Higher values of commitment levels were found in the study developed by Batugal and Tindowen (2019) that involved professors from a Catholic higher education institution in the Philippines. The results of this study showed that respondents were highly committed to their organization (Global commitment: mean = 5.18; affective commitment: mean = 5.42; calculative commitment: mean = 4.66; normative commitment: mean = 5.45). However, the same trend was found, that is, the highest level of commitment was recorded in affective commitment and the lowest was found in normative commitment. For Osibanjo, Oyewunmi, Abiodun and Oyewunmi (2019) and Nguyen, Nguyen and Le (2021), the greater the level of organizational commitment, the greater the participation of employees as well as the level of job satisfaction. In addition, a study developed by Rasouli, Rashidi and Hamidi (2014) involving 256 higher education teachers from South Khorasan province, concludes that job satisfaction through organizational commitment can predict the intention of knowledge collaborators to remain in the institution.

For Luthans (1995), the factors that influence commitment could be of a different nature, namely: personal factors including age, gender and hierarchical position in the organization; organizational factors including autonomy, working hours, challenges at work and the challenges for which they are responsible; and, non-organizational factors, external to the organization, for example, the existence of better work in another organization. Similar results were obtained by Pearce (1993); however, they contradict the findings of Van Dyne and Ang (1998). In fact, according to these authors, workers with fixed-term contracts showed lower levels of affective commitment than workers with uncertain-term contracts.

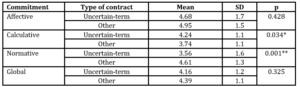

Taking into account the type of employment contract, Table 6 shows that, at the level of affective and global commitment, there were no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05), although the levels of commitment are slightly higher in individuals with another type of contract, other than the contract for an indefinite period or uncertain-term contract, namely, fixed-term contract or scholarship holder. In addition, statistically significant differences were recorded in the levels of calculative (p = 0.034 < 0.05) and normative (p = 0.001 < 0.05) commitment. In the calculative commitment, respondents with an uncertain-term contract have the highest levels, whereas in the normative commitment, the exact opposite is verified. That is, the respondents in a more precarious professional situation are the ones who register the highest values. Identical results were found by Batista (2016). Borchers and Teahen (2001) concluded that the level of commitment was sensitively the same between full-time and part-time teachers or between those who taught online or face-to-face.

Table 6: Level of organizational commitment by type of employment contract

* significant at 0.05

** significant at 0.01

Conclusions

This quantitative, cross-sectional and observational research aimed: (1) to determine the level of organizational commitment of employees of a public higher education institution, located in the Trás-os-Montes region, located in the Northeast of Portugal; and (2) to verify if the level of commitment was the same for all employees of the institution, regardless the type of employment contract. In this context, a sample of 105 employees out of 783 was collected.

The results showed that the level of global organizational commitment was moderate. Taking into account the three-dimensional model of organizational commitment, the employees who participated in this study registered a high level of affective commitment, and the levels of organizational commitment in the normative and calculative dimensions were moderate. Furthermore, it was found that the type of employment contract was a differentiator factor of calculative and normative organizational commitment levels. And, in the calculative commitment, respondents with an uncertain-term contract were those with the highest levels of organizational commitment. In the normative commitment, the respondents that were in an uncertain professional situation (fixed-term contract) were those who register the highest values of organizational commitment.

Based on the results obtained, measures are recommended to be implemented by the Management of the Public Higher Education Institution to strengthen the levels of commitment of employees who have been moderated in terms of global, normative and calculative commitment. Designing and implementing compelling, productive and effective policies that encourage employee prosperity as well as organizational productivity, is critical to the success of organizations (Arokiasamy & Tat, 2019). Human resources play a significant role in all strategic decisions made by organizations. These findings may help managers to develop effective strategies that promote employee satisfaction and organizational commitment (Nguyen, Nguyen & Le, 2021). In the opinion of Bauwens, Audenaert, Huisman and Decramer (2017), the academic community tends to be more committed when the institutions adopt fair and transparent procedures in decision-making and in the allocation of resources. Contributions that promote investment in talent and a positive social environment are reflected in higher levels of commitment, motivation and performance on the part of employees (Barrena-Martínez, López-Fernández & Romero-Fernández, 2019). In this context, it is up to higher education institutional managers to prioritize specific dimensions of quality of life at work for employees as an integral antecedent to achieving global organizational goals (Osibanjo, Oyewunmi, Abiodun & Oyewunmi, 2019).

A limitation of this study may be the low number of responses obtained (13.41%) that makes the sample not representative of the population. Although, it is known that low response rates are not necessarily related to the quality of the results, the usual precautions regarding the generalization of results should be applied. Another limitation is the cross-sectional typology of the study. In this type of studies, data collection was carried out in a single moment. In this context, according to Ferreira and Carreira (2019), the results may emerge from specific interpretations of the participants or be influenced by contextual or personal factors. Thus, it is suggested that, in future research, longitudinal data should be used in order to measure the level of organizational commitment and to verify if it changes or is maintained considering the effect of time and the professional experience of the employees.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) for financial support through national funds FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC) to CIMO (UIDB/00690/2020 and UIDP/00690/2020) and SusTEC (LA/P/0007/2020).

The authors are also grateful to the Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing and UCISA (E – Núcleo da Escola Superior de Saúde do Instituto Politécnico de Bragança).

References

- Allen, N.J. and Meyer, J.P. (1990). ‘The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization.’ Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63 (1), 1–18.

- P.G. and Priyambodo, A.B. (2021). ‘Correlation Between Organizational Commitment and Employee Performance When Working from Home During the Covid-19 Pandemic.’ International Conference of Psychology 2021 (ICoPsy 2021), 55–66.

- Arokiasamy, A.R.A and Tat, H.H. (2019). ‘Organizational culture, job satisfaction and leadership style influence on organizational commitment of employees in private higher education institutions (PHEI) in Malaysia.’ Amazonia Investiga, 8 (19), 191-206.

- Ashford, S.J., George, E. and Blatt, R. (2007). ‘Old assumptions, new work: The opportunities and challenges of research on nonstandard employment.’ The Academy of Management Annals, 1 (1), 65–117.

- Barrena-Martínez, J., López-Fernández, M. and Romero-Fernández, P.M. (2019). ‘Towards a configuration of socially responsible human resource management policies a+nd practices: findings from an academic consensus.’ The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30 (17), 2544-2580.

- Batista, M. (2016) Comprometimento Organizacional: Trabalhadores Temporários e Trabalhadores da Empresa Utilizadora, Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal, Portugal.

- Batugal, M.L.C. and Tindowen. D.J.C. (2019). ‘Influence of Organizational Culture on Teachers’ Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction: The Case of Catholic Higher Education Institutions in the Philippines.’ Universal Journal of Educational Research, 7 (11), 2432-2443.

- Bauwens, R., Audenaert, M., Huisman, J. and Decramer, A. (2017). ‘Performance management fairness and burnout: Implications for organizational citizenship behaviors.’ Studies in Higher Education, 44 (3), 584-598.

- Booth, A. L. (2002). ‘Temporary jobs: Stepping stones or dead ends.’ The Economic Journal, 112 (480), 189-213.

- Borchers, A. S. and Teahen, L. (2001). ‘Organizational commitment of part-time and distance faculty.’ AMCIS2001 Proceedings, 204-207.

- Ferreira, I. and Santos, M. (2013). ‘Análise da utilização de trabalho temporário em empresas portuguesas: riscos e alternativas.’ International Journal on Working Conditions, 5, 18-38.

- Ferreira, M.P.J. and Carreira, P.M.R. (2019). ‘A influência da flexibilização do trabalho no comprometimento organizacional e na intenção de abandono: um estudo com os trabalhadores estudantes do ensino superior português.’ International Journal on Working Conditions, 18, 145-169.

- Glaymann, D. (2008). ‘Pourquoi et pour quoi devient-on intérimaire?’ Travail et Emploi, 114 (2), 33-43.

- Gouveia, C. (2019). Contratualização interna no CHULC – Comprometimento de médicos e enfermeiros no internamento, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal.

- Granovetter, M. (2018) Getting a job: A study of contacts and careers, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Hollenbeck, J. and Jamieson, B. (2015). ‘Human capital, social capital and social network analysis: Implications for strategic human resource management.’ Academy of Management Perspectives, 29 (3), 370-385.

- Horta, H., Jung, J., Zhang, L. and Postiglione, G.A. (2019). ‘Academics’ job-related stress and institutional commitment in Hong Kong universities.’ Tertiary Education and Management, 25, 327–348.

- Jordan, G., Miglic, G., Todorovic, I. and Maric, M. (2017). ‘Psychological Empowerment, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment Among Lecturers in Higher Education: Comparison of Six CEE.’ Organizacija, 50 (1), 17-32.

- Kaplan, A. M. and Haenlein, M. (2016). ‘Higher education and the digital revolution: About MOOCs, SPOCs, social media, and the Cookie Monster.’ Business Horizons, 59 (4), 441-450.

- Khasawneh, S., Omari, A. and Abu-Tineh., A. (2012). ‘The Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Organizational Commitment: The Case for Vocational Teachers in Jordan.’ Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 40 (4), 494–508.

- Lesley, P. (2018) The University Challenge (2004): Higher Education Markets and Social Stratification. Routledge, London and New York.

- Lima, C.C.A. and Rowe, D.E.O. (2019). ‘Percepção das políticas de gestão de pessoas e comprometimento organizacional em uma universidade pública.’ Revista Gestão Organizacional, 12 (14), 118-137.

- Lizote, S. and Morais, M. (2021). ‘Percepção dos professores e alunos sobre a relação entre o comprometimento organizacional e os resultados da avaliação institucional.’ Anais do XX Colóquio Internacional de Gestão Universitária CIGU 2021, 1-15.

- Lizote, S.A., Verdinelli, M.A. and Nascimento, S. (2017). ‘Relação do comprometimento organizacional e da satisfação no trabalho de funcionários públicos municipais.’ Revista de Administração Pública, 51 (6), 947-967.

- Luthans F. (1995) Organizational behavior, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Marôco, J. (2018) Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics, ReportNumber, Pero Pinheiro.

- Meyer, J. P. and Herscovitch, L. (2001). ‘Commitment in the workplace: toward a general model.’ Human Resource Management Review, 11 (3), 299–326.

- Meyer, J.P. and Allen, N.J. (1997) Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Meyer, J.P., and Allen, N.J. (1991). ‘Three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment,’ Human Resource Management Review, 1 (1), 61-89.

- Nascimento, J.L., Lopes, A. and Salgueiro, M.F. (2008). ‘Estudo sobre a validação do Modelo de Comportamento Organizacional de Meyer e Allen para o contexto português.’ Comportamento Organizacional e Gestão, 14, 115–33.

- Nawaz, K., Usman, M., Qamar, H.G.M., Nadeem, M. and Usman, U. (2020). ‘Investigating the Perception of Public Sector Higher Education Institution Faculty Members about the Influences of Psychological Contract on Organizational Commitment.’ American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 10, 144-159.

- Nguyen, P.N.D., Nguyen, L.L.K. and Le, D.N.T. (2021). ‘The Impact of Extrinsic Work Factors on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment a Higher Education Institutions in Vietnam.’ Journal of Asian Finance Economics and Business, 8 (8), 259-270.

- Nunnally, J. and Bernstein, I. (1994) Psychometric theory, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Oliveira, H.H. and Honório, L.C. (2020). ‘Práticas de recursos humanos e comprometimento organizacional: Associando os construtos em uma organização pública.’ Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 21 (4), 1–28.

- Osibanjo, O.A., Oyewunmi, A.E., Abiodun, A.J. and Oyewunmi, O.A. (2019). ‘Quality of work-life and organizational commitment among academics in tertiary education.’ International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, 10 (2), 418-430.

- Paugam, S. (2000) Le salarié de la précarité, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

- Pearce, J. (1993). ‘Toward an organizational behavior of contract laborers: Their psychological involvement and effects on employee co-workers.’ Academy of Management Journal, 36 (5), 1082-1096.

- M. and Gageiro, J. (2014) Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais: A Complementaridade do SPSS, Edições Sílabo, Lisboa.

- Pinho, A.P.M. and Bastos, A.V.B. (2014) Vínculos do trabalhador com a organização: comprometimento, entrincheiramento e consentimento, Hucitec, São Paulo.

- Pinho, A.P.M. and Oliveira, E.R.S. (2017). ‘Comprometimento organizacional no setor Público: um levantamento bibliográfico dos últimos 27 anos no Brasil.’ Anais do Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação em Administração, 1-17.

- Pucciarelli, F. and Kaplan, A. (2016). ‘Competition and strategy in higher education: Managing complexity and uncertainty.’ Business Horizons, 59 (3), 311-320.

- Rasouli, R., Rashidi, M. and Hamidi, M. (2014). ‘A Model for the Relationship between Work Attitudes and Beliefs of Knowledge Workers with Their Turnover Intention.’ Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences, 22 (2), 149-155.

- Rebelo, G. (2006) Flexibilidade e Diversidade Laboral em Portugal, Dinâmia: Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica, Lisboa.

- Rusu, R. (2011). ‘Organizational commitment forms in higher education institutions in Romania.’ 17th International Conference Knowledge-Based Organization, Conference Proceedings 1: Management and Military Sciences.

- Subair, S.T., and Talabi, R.B. (2015). ‘Teacher shortage in Nigerian schools: Causes, effects administrators coping strategies.’ Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences, 2 (4), 31-37.

- Thomas, J.C. (2008). ‘Administrative, Faculty, and Staff Perceptions of Organizational Climate and Commitment in Christian Higher Education.’ Christian Higher Education, 7 (3), 226-252.

- Van Dyne, L. and Ang, S. (1998). ‘Organizational citizenship behavior of contingent workers in Singapore.’ Academy of Management Journal, 41 (6), 692–70