Introduction

Leadership is a tool that enables people to achieve common goals in a more efficient way than if they try to do so separately. In fact, some tasks are even impossible to fulfill individually. Rather than process of leading people by one person, it can be viewed as process of following one person by others, i.e., followership. At the end of the day, it is mostly followers’ behavior that finally determines whether leadership is efficient or not (Dixon, 2008).

When investigating the cornerstones of an efficient leadership, military environment is often utilized due to its naturally high demands on serving personnel. Hannah et al. (2009) argue that in such an extreme context that puts people in the face of high physical, mental, or material risk, leadership becomes uniquely contextualized. Yet, many of the findings from this context are subsequently translated and utilized in civilian life, as demonstrated by Fiedler’s (1955, 1966) contingency model of leadership, which has its origins in military studies. As changes in modern warfare require front-line soldiers to operate in small cohesive units and their leaders to make the right decisions in complex and often dilemmatic situations with higher levels of autonomy (Řehka, 2018), Michelson (2013) suggests that an officer’s character, “who they are as a person”, matters more than ever before. Under these conditions, the concept of character-based leadership, defined in this paper as “leadership process at which leader is followed due to their character traits as perceived by their followers”, gains importance.

Literature Review

Although character might be reasonably considered a critical aspect of leadership, determining which character traits are conducive to its efficacy is yet subject to research. Matthews et al. (2006) compared developing military leaders from United States Military Academy and Royal Norwegian Naval Academy. Both groups rated as five of their top seven strengths Honesty, Kindness, Industriousness, Curiosity, and Hope. Matthews (2011) also examined commander after their return from combat deployments. Traits that they marked as most contributing to success in combat were Honesty, Persistence, Bravery, Capacity to love, and Teamwork.

Gayton and Kehoe (2018) conducted a study of Australian Defense Force junior officers. Besides Leadership, their strongest personal strengths were Integrity, Trustworthy, Good Judgment, and Team Worker. Participants were also asked to rate five top strengths of their subordinates. Mean profiles of both groups significantly overlapped; significant differences were registered only for Trustworthiness (ranked higher among junior officers’ strengths) and Wisdom (ranked higher at their subordinates). Obe, Walker, and Thoma (2018) researched character traits of junior officers from twelve branches of service of the British Army. On average, highest scores were reported for Fairness, Honesty, Perseverance, Teamwork, and Curiosity.

In the recent study of Czech Army officers (Heřman et al., 2022), cadets and soldiers serving in reconnaissance units rated Fairness, Honesty, Teamwork, Leadership, Perspective, Creativity, Love of Learning, and zest highest in officers they perceive as excellent. The strong correlation between officers’ profiles in all the groups (rs = .82–.86) suggest that perception of character-based leadership may remain stable throughout a soldier’s career. As the mean relationship between a leader’s and a follower’s self-reported traits was negligible (rs = .18), it is reasonable to assume that the perception of a leader’s character is not necessarily a projection of an individual’s own traits or desires, and subordinates might tend to follow similar leaders regardless of their self-image. Multiple regression models aimed at proposing a combination of character traits that contribute to the officer’s perceived efficacy most frequently involved Fairness, Honesty, Kindness, and Social Intelligence, while Forgiveness was negatively associated with these parameters.

Most of the existing research on military leaders’ character traits, including all of the above-mentioned studies, is based on the classification of Values in Action Institute on Character (VIA). This taxonomy was created by Peterson and Seligman (2004) and comprises of 24 character strengths, described in Character Strengths and Virtues Handbook (CSV). Using this framework, there was conducted extensive research in Norwegian Army (Boe & Bang, n.d., 2017; Boe, Bang, & Nilsen, 2015a, 2015b) to identify traits that are specifically important for their officers. However, the authors also found that the VIA Inventory of Strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) only weakly predicts character traits displayed under field conditions (Bang et al., 2015) and that leadership efficacy is better predicted by others’ rating of a leader’s character compared to a self-report. Therefore, they extracted selected strengths from CSV and created new items to measure them from the perspective of an officer’s subordinates (Bang et al., 2016). Their latest study (Bang et al., 2021) has shown that the mean score of “military” character traits outperforms general mental ability with regard to prediction of academic and military performance.

Research Question

Although VIA model seems to insufficiently capture the specifics of military character-based leadership, other methodological approaches are rarely utilized. Molen (2010) collected data on the most frequently mentioned strengths of U.S. Army officers who have experience with deployment, using a qualitative survey. However, his content analysis finally focused on identifying character traits as defined by VIA. There are recently published papers on character strengths of a leader as reflected in military core values (Heřman, Ullrich, & Mikulka, 2021), insignias, and memoirs (Heřman, & Ullrich, in press), but qualitative methods are still generally underused in research on this topic, even though they have a great potential to deepen our understanding of it and temper the content and construct validity of its models.

The present study strives to expand knowledge on character-based leadership by using complementary qualitative methodology in order to investigate it without reducing to a specific theoretical framework. Drawing on a sample of the Czech Land Forces personnel, it is aimed to deal with the following question: What character traits of an officer are most valued by their subordinates?

Design and Methodology

Sample

Participants (N = 40) were recruited from active-duty personnel of the Army of the Czech Republic. A sample of 40 soldiers was recruited from the 44th Light Motorized Battalion of the Army of the Czech Republic. This combat unit is designated for convoy protection, quick offensive operations, reconnaissance, and headquarters defense, being the only of its kind in the Czech Land Forces (Ministry of Defense, n.d.). Except one female, all of the participants were male (97.5%). By the time when the data collection took place, most of them were in a partner relationship (87.5%) and almost half of them had children (47.5%). Regarding the proportion of leaders and followers, the sample was not significantly unbalanced, with 23 participants (57.5%) having the function of squad, platoon, or company commander/deputy commander and 17 participants (42.5%) being assigned to a non-command function. 65.0% reported experience with being deployed abroad and 30.0% have served on airborne post in the past.

The mean age of participants was 29.4 years (SD = 4.0), ranging from 21 to 37 years. No significant differences between the subgroups of participants with/without airborne experience and command/non-command function were registered. The number of years served in the army ranged from 0 to 17 years (M = 6.2, SD = 3.7).

Measures And Procedure

The present study builds on qualitative design and methodology. For the data collection, the following three open-ended questions (further on also referred to as abbreviated in the brackets) were administered:

Question 1 (Q1): In your opinion, what characterizes an officer that has a good character?

Question 2 (Q2): In your opinion, what are the best character traits that an officer can have?

Question 3 (Q3): What do you perceive as character traits of your officer?

All of these questions focus on the same thing – valued character strengths of an officer – while using different perspectives. Q1 operationalizes character-based leadership in the military as a set of characteristics that can be registered by an external observer. Q2 focuses directly on important character strengths of an officer as perceived by their subordinates. While Q2 is rather hypothetical, Q3 is behavioral-based, assessing participants’ personal experience with a current leader. Phrase “in your opinion” in Q1 and Q2 is intended to eliminate avoidant answers such as “That is up to everyone’s perception.”

The data were collected face to face in pen-and-paper form in December 2021. The three questions were presented to participants in the beginning of a test battery, which further included other measures that are not evaluated in this paper. The number of three questions was chosen to adhere to the principle of triangulation, i.e., increasing the validity of qualitative research outcomes by using three or more methods or sources of data (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007), while maintaining low time requirements.

Analysis

The pen-and-paper data were first converted into digital form. Answers as “see question 1” were replaced with literal quotation of the items they referred to. However, these kinds of answers only occurred several times. Next, content and frequency analyses were performed. Content analysis was inspired by the grounded theory of Glaser and Strauss (1967). As the central category of “valued character traits of a leader” was given a priori, the coding was executed on the open and axial level, aiming to identify separate categories of particular traits. Expressions were clustered into categories based on their synonymity and authors’ expert knowledge on the topic of character traits. By comparing and contrasting, the terms with similar but not identical meaning (e.g., “honesty” and “integrity”) were differentiated in this step, too. Phrases describing certain traits without naming them (e.g., “He treats everyone the same.”) were handled as relevant strengths (e.g., justice in this case). On the other hand, vague mentions of unspecified strength-related behavior (e.g., “…according to how he decides in a stressful situation.”) were not considered as traits.

To estimate the relative importance of identified traits, the categories were further ordered by their absolute frequencies in the data, obtained by the method of simple enumeration. If a participant described one strength using several synonyms or phrases (e.g., “honest” and “straightforward”), it was counted as one answer. Final designation of each category was determined based on the frequency and/or the aptness of selected expression, with in vivo coding often used.

Ethics

All participants of the present study were of the age of the majority. Their participation was voluntary and they were free to withdraw at any stage. They were informed of the purpose of the study and the confidentiality of their data, which were secured by anonymizing the test batteries. They were also given the opportunity to ask questions, and it was explained how to get acquainted with the results once they are available. The study was approved by the unit’s commanding officer. It was conducted under the supervision of representatives of the University of Defense, which is a guarantee of the research for the Chief of the General Staff of the Army of the Czech Republic.

Results

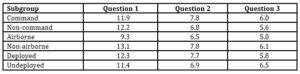

All addressed participants confirmed their consent to participate in the research and submitted their data. As illustrated in Table 1, the mean length of responses generally tends to decrease throughout the questions. Most notable differences are present at soldiers who have served on airborne post in the past and express themselves more briefly compared to those without their experience.

Table 1: Mean length of responses

The following sections describe the results of content and frequency analysis of individual questions and then all of them merged together.

Signs of a good character in a leader

Among the characteristics of an officer that has a good character as reported by participants, Justice (f = 16) clearly dominates. Some participants refer to it as “fairness” or “impartiality” and describe it as treating everyone equally and not using double standards. Other frequently mentioned traits include Honesty (f = 7; syn. straightforwardness, directness, truthfulness), Decisiveness (f = 6), and Dependability (f = 5; syn. responsibility). There also occurs a broader cluster of positivity, optimism, and sense of humor (f = 4), valued at the officer.

Participants also described a few behavioral characteristics of a leader they perceive as having a good character. One of those is setting an example (f = 5) by following what they require of their subordinates. They also appreciate standing up for their people (f = 4) and taking care of them (f = 3). Moreover, there were several mentions addressing officer’s social skills: “is a support to people,” “people come to them to get advice,” “contributes to building good relationships,” and “connects people.”

Best character traits of a leader

In responses to Q2, highest frequencies of particular traits were registered. Besides Justice (f = 23), Decisiveness (f = 12), and Honesty (f = 9), being the most significant ones again, Purposefulness (f = 7) was notable, described as that a leader “cares about the task completion”. Next, there occurred two clusters of different attributes of the same trait – Willingness (f = 6; incl. helpfulness, approachability, openheartedness) and Humanity (f = 6; incl. empathy, perceptiveness, comprehension). In a given context, the latter can be defined as “being considerate of followers’ emotions and needs”.

Other valued characteristics of a leader were dominated by intelligence (f = 7; incl. cleverness, sensibleness, judgment), standing up for their people (f = 5), and trustworthiness (f = 5).

Perceived character traits of participants’ own leaders

Contrary to two previous questions, the most frequently perceived strength of participants’ own leaders is Humanity (f = 10), followed by Justice (f = 9) and honesty (f = 8). In this case, Decisiveness (f = 5) was surpassed by the cluster of Willingness (f = 6; incl. helpfulness, approachability, openheartedness). Besides Dependability (f = 5) and Purposefulness (f = 4), some participants also appreciate industriousness (syn. sense of duty; f = 4) of their leaders.

Among the valued abilities of a leader, besides intelligence (f = 7), participants value officers who can motivate others and are motivated themselves (f = 6). It is worth mentioning that part of the sample further reported negatively perceived traits of their leaders as well. However, these are not discussed, as the present study focuses on the positive form of character-based leadership.

Summary

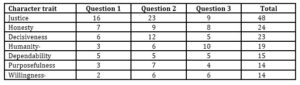

Table 2 displays the most frequently reported character traits of a leader across the whole dataset.

Table 2: Most frequently reported character traits of a leader

Besides the above-mentioned traits, other generally valued strengths were Positivity (f = 12; incl. optimism, sense of humor) and Courage (f = 9; syn. fearlessness). Summing up the previous sections, other characteristics of an officer that do not fall into the category of character traits, yet they were frequently reported by participants, include intelligence (f = 16), standing up for the subordinates (f = 10), setting an example (f = 8), motivating (f = 8) and being trustworthy (f = 7). Part of the sample also appreciates when the leader possesses self-confidence (f = 6; syn. self-assurance, self-reliance, assertiveness) and informal authority (f = 4) but also considers different opinions and perspectives (f = 6) and admits their own mistakes (f = 4).

Discussion

The final list of the most frequently mentioned character traits may be a specification of what “setting an example” and “being trustworthy” means in particular to a leader. Top leader’s strength identified in this study, Justice, may fulfill these principles in the sense of being fair to followers by keeping the same rules as them and treating all of them equally. While some authors handle the terms Honesty and Integrity as interchangeable, in the present study, they are distinguished. While Honesty is mostly bound to interaction with other people, in which sincerity, openness, straightforwardness, truthfulness, and others of its aspects can be shown, integrity is more related to being fair to oneself when “no one is watching”, and as such, it has more in common with fairness, i.e., Justice. Although Courage was not as frequent as other top strengths, it constitutes a necessary prerequisite of Decisiveness, when understood as the ability to make quick and right decisions even under stressful conditions. In practice, clusters of Humanity and Willingness attributes may be related to each other, as individuals who are willing to help others are those who are usually also able to be aware of others’ needs. Leaders who demonstrate these qualities will also probably be those who take care of their followers. Similarly, Purposefulness and Dependability may often occur together as both of these traits are outcome-focused.

Decisiveness ranked higher in the first two hypothetical questions on officer’s character than in responses to strengths perceived at participants’ own leader. Conversely, Humanity and Willingness ranked just the opposite way. The reason for that might be that the latter two are more associated with followers’ positive emotions, while Decisiveness of a leader rather preserves them from experiencing negative consequences of critical situations. When it comes to reported officer’s characteristics other than character traits, it is interesting that intelligence ranked first in both Q2 and Q3, while in Q1, it was mentioned marginally. The same phenomenon occurs for trustworthiness, which was notably emphasized in Q2 but not in the other two questions. One possible explanation is that these two characteristics are valuable, yet it takes followers longer time to recognize them at the leader.

Although not consistently appearing as significant in the previous research, Justice is by far the most frequently reported strength of an officer in the present study. With regard to Honesty, there is an estimated consistency between the previous findings and our results. Humanity and Willingness as understood in this paper resemble Peterson’s and Seligman’s Social Intelligence and Kindness, respectively. Perseverance, frequently figuring amongst leader’s top strengths in other studies, might be partially associated with Purposefulness, as VIA (n.d.) relates it with persistence toward goals. Conversely, Decisiveness and Dependability constitute suggested traits of a leader, which CSV (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) does not capture.

A trait that was repeatedly reported as one of the officers’ top strengths but is almost completely missing in the present results is Teamwork. There are at least two important things to be considered when interpreting this discrepancy. First, even though the participants did not literally mention it, standing up for the subordinates might be considered as a demonstration of Teamwork by the officer. Second, it is possible that Teamwork constitutes such a foundational principle of the military that participants may not think of emphasizing in relation to leadership.

The present results display interesting similarities with the recent study of Czech Army officers’ character strengths (Heřman et al., 2022). Pairing responses to questions used in the present study (in brackets) with regression models of perceiving an officer as having a good character (Q1), being successful (Q2), and being a leadership example (Q3) from the latter study, reveals remarkable overlaps. Regarding the signs of a leader that has a good character, Justice/Fairness, Honesty, and Humor are shared. As for the leader’s excellence, Justice/Fairness, Humanity/Social Intelligence, Willingness/Kindness, and Perseverance/Purposefulness are common. With regard to the perception of leadership example, Justice/Fairness, Honesty, Humanity/Social Intelligence, and Willingness/Kindness are present in both studies. These findings support the idea of character-based leadership as a set of particular traits of a leader that emerge as important despite using different methodologies.

Limitations and future directions

The chosen research design naturally generates results that can serve as a basis for hypotheses but cannot be generalized. It also cannot prove the causal effect of identified variables on leadership. However, considering its primarily exploratory focus, the latter fact does not decrease the value of obtained outcomes that can complement the findings of quantitative and experimental studies. Nevertheless, without further examination, it is possible to apply them only to a limited extent. In this context, uniqueness of the present sample also must be considered, as soldiers of 44th Light Motorized Battalion are not representative even of the Czech Army, not to mention other countries’ armed forces, given the fact that nations differ at least in several basic dimensions (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010).

The data collection that took place at a single point of time cannot capture possible development of followers’ perception of a leader’s traits. In accordance with the current emphasis on item response theory (Lord, 1952), i.e., taking into account that items may function differently for different people, it is obvious that similar or even identical responses to open-ended questions might actually have a different meaning to individual participants as well. Moreover, the research of human memory has previously revealed plenty of cognitive biases related to recalling memories of the past (Schacter, 1999). Considering that mapping of important character traits of a leader in the present study is based on participants’ mental representations of leaders, it is reasonable to assume that they will more or less deviate from reality, while this distortion can never be fully removed. It is also true that some of the character traits of a leader might be generally less available to extrospection. However, it is questionable how important they are for leadership practice, considering the problematics of their measurement and objective evaluation of their development.

Future research on this topic first requires replications across different contexts. If the same questions are used, it can be specified in formulation of Q2 that the participant is asked to state positive traits of their immediate superior, which was not completely clear in the present study. Furthermore, it is desirable to quantify the relative importance of particular strengths and their relation to leadership efficacy. For internal comparison of character-based leadership components, a forced-choice method with even-numbered response scale can be utilized. As a criterion of leadership efficacy, the annual evaluation score of a leader and their team can be applied. In case of a quantitative study, desirability should be always measured, as it frequently causes bias in military studies when not controlled.

Conclusion

The present study achieved its aim. Character traits of a leader that are most frequently reported by their followers among selected Czech Army personnel are Justice, Honesty, Decisiveness, Humanity, Dependability, Purposefulness, and Willingness. Although it was not a primary focus of the study, several other characteristics of effective leaders that do not fall into the category of character traits were identified, most notably intelligence, standing up for the subordinates, setting an example, motivating, and trustworthiness.

These findings contribute to the existing research by suggesting specific components of character-based leadership generated by using more inclusive methodological approach. Considering that many of the findings from military studies are subsequently translated to other areas of society, the results provide valuable insight into what effective leadership may be associated with in general. With regard to the selection and development of leaders, organizations may profoundly benefit from deeper knowledge of character traits that are important for their followers, whose behavior finally determines the efficacy of a leadership process in any context. For future research on this topic, replications across different contexts can be recommended.

References

- Bang, H., Boe, O., Nilsen, F. A. and Eilertsen, D. E. (2015), ‘Evaluating Character Strengths in Cadets During a Military Field Exercise: Consistency Between Different Evaluation Sources,’ EDULEARN15 Proceedings, ISBN: 978-84-606-8243-1, 6-8 July 2015, Barcelona, Spain, 7076-7082.

- Bang, H., Eilertsen D. E., Boe, O. and Nilsen, F. A. (2016), Development of an Observational Instrument (OBSCIF) for Evaluating Character Strengths in Army Cadets. EDULEARN16 Proceedings, ISBN: 978-84-608-8860-4, 4-6 July 2016, Barcelona, Spain, 7803-7808. https://doi.org/10.21125/edulearn.2016.0711

- Bang, H., Nilsen, F., Boe, O., Eilertsen, D. E. and Lang-Ree, O. C. (2021), ‘Predicting Army Cadets’ Performance: The Role of Character Strengths, GPA and GMA,’ Journal of Military Studies, 10 (1), 139-153.

https://doi.org/10.2478/jms-2021-0016

- Boe, O. and Bang, H. (2017), ‘The Big 12: The Most Important Character Strengths for Military Officers,’

Athens Journal of Social Sciences, 4 (2), 161-174. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajss.4-2-4

- Boe, O. and Bang, H. (n.d.), Risk Seeking and Character Strengths in Military Officers, Norwegian Military Academy.

- Boe, O., Bang, H. and Nilsen, F. A. (2015a), ‘Selecting the Most Relevant Character Strengths for Norwegian Army Officers: An Educational Tool,’Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197 (2), 801-809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.188

- Boe, O., Bang, H. and Nilsen, F. A. (2015b), ‘Experienced Military Officer’s Perception of Important Character Strengths: An Educational Tool,’Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 190 (2), 339-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.05.008

- Dixon, G. (2008), ‘Followers: The Rest of the Leadership Process,’ SAE International Journal of Materials and Manufacturing, 1 (1), 255-263. https://doi.org/10.4271/2008-01-0549

- Fiedler, F. E. (1955), ‘The Influence of Leader-Keyman Relations on Combat Crew Effectiveness,’

Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 51 (2), 227-235. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040393

- Fiedler, F. E. (1966), ‘The Effect of Leadership and Cultural Heterogeneity on Group Performance:

A Test of the Contingency Model,’ Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 (3), 237-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(66)90082-5

- Gayton, S. D. and Kehoe, E. J. (2018), ‘Character Strengths of Junior Australian Army Officers,’

Military Medicine, 184 (5-6), 147-153. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy251

- Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1967), The Discovery of Grounded Theory Strategies for Qualitative Research, Sociology Press, Mill Valley.

- Hannah, S. T., Uhl-Bien, M., Avolio, B. J. and Cavarretta, F. L. (2009), ‘A Framework for Examining Leadership in Extreme Contexts,’ The Leadership Quarterly, 20 (6), 897-919. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.09.006

- Heřman, O. and Ullrich, D. (in press), ‘Valued Character Strengths of a Leader as Reflected in Military Traditions and Memoirs,’ ICERI2022 Proceedings, 7-9 November 2022, Seville, Spain.

- Heřman, O., Mac Gillavry, D. W., Höschlová, E. and Ullrich, D. (2022), ‘Character Strengths

of Czech Army Excellent Officers as Perceived by Cadets and Soldiers Serving in Reconnaissance Units,’

Military Medicine. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usac253

- Heřman, O., Ullrich, D. and Mikulka, Z. (2021), ‘Theoretical bases of character-based leadership in the army,’ EDULEARN21 Proceedings, ISBN: 978-84-09-31267-2, 5-6 July 2021, Online Conference, 2470-2478. https://doi.org/10.21125/edulearn.2021.0538

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede G. J. and Minkov, M. (2010), Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (3rd ed.),

McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Leech, N. L. and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007), ‘An Array of Qualitative Data Analysis Tools: A Call for Data Analysis Triangulation,’ School Psychology Quarterly, 22 (4), 557-584. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

- Lord, F. M. (1952), A Theory of Test Scores, Psychometric Monograph No. 7., Psychometric Corporation, Richmond.

- Matthews, M. D. (2011, August 7), ‘Character Strengths and Post-Adversity Growth in Combat Leaders,’ [Poster presentation], 119th Annual Meeting of the Conference of the American Psychological Association,

4-7 August 2011, Washington, U.S.A.

- Matthews, M. D., Eid, J., Kelly, D., Bailey, J. K. S. and Peterson, C. (2006), ‘Character Strengths and Virtues of Developing Military Leaders: An International Comparison,’ Military Psychology, 18 (1), 57-68. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327876mp1803s_5

- Michelson, B. M. (2013), Character Development of U.S. Army Leaders: A Laissez Faire Approach, U.S. Army War College, Carlisle Barracks.

- Ministry of Defense. (n.d.), ‘O nás,’ army.cz. [Online], [Retrieved 2022], https://44lmopr.army.cz/o-nas

- Molen, R. J. V. (2010), ‘Character strengths and emotions in military leaders,’ unpublished bachelor’s thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Obe, J. A., Walker, D. I. and Thoma, S. (2018), Soldiers of Character: Research Report, University of Birmingham.

- Peterson, C. and Seligman, M. E. P. (2004), Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification, American Psychological Association, Washington.

- Řehka, K. (2018), ‘Požadavky a dopady v armádní praxi,’ Colloquium on the Management of the Educational Process “Leadership – theory and practice”, ISBN: 978-80-7582-082-2, 2018, Brno, Czech Republic, 5-11.

- Schacter, D. L. (1999), ‘The Seven Sins of Memory: Insights from Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience,’ American Psychologist, 54 (3), 182-203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.182

- Values In Action Institute on Character. (n.d.), ‘Find Your 24 Character Strengths,’ VIA Institute. [Online], [Retrieved 2022], https://www.viacharacter.org/character-strengths-via