Introduction

There is no question that social media is fundamentally changing the way many marketers communicate with their customers. With the advent of cost-efficient Internet messaging, organizations now communicate with scores of customers in ways that are revolutionary. Traditional print and broadcast media have seen declines in revenue due to the movement of advertising dollars to online alternatives. Social media is the latest alternative for organizations to leverage online communications. Social media is a more open, grassroots, and organic approach compared to traditional marketing (Baker, 2009). The research, planning, implementation strategies and tactics are different. As revolutionary as this new media form may seem, it should be integrated with, not supplant, traditional media; media synergy is important (Marken, 2009).

Similarly, consumers consume this media in a different way and have more control in terms of when, where and how they interact with organizations (Baker, 2009; Marken, 2009; Palmer and Koenig-Lewis, 2009; Saperstein and Hastings, 2010). Despite the potential benefits to an organization, an online com-munity dominated by consumers may be dif-ficult for a company to influence, and may yield resentment if the company attempts to exert its influence. And if achieved, seller dominance may lose the benefits of commu-nity involvement.

Social Media Defined

Social media, also consumer-generated media (CGM), is a key element of Web 2.0, the latest level of online technology (Anonymous, 2007b). Social media is such a significant component of Web 2.0, that the two terms are often used interchangeably. It is defined as, “online applications, platforms and media which aim to facilitate interactions, collaborations and the sharing of content” (Palmer and Koenig-Lewis, 2009, p. 165). Its forms include text, images, audio and video (Thevenot, 2007; Tulgan, 2007). Popular social media include blogs and micro-blogs, vlogs, podcasts, and wikis (Anonymous, 2007b; Baker, 2009; Thevenot, 2007; Tulgan, 2007).

Blogs, or personal weblogs, are digital diaries for recording “personal or professional experiences or for sharing news and commentary” (Hawn, 2009, p. 363). Alternatively, it is “a combination of a person’s personal life and the particular subject they would like to provide comments or information on” (Thevenot, 2007, p. 282). They are the equivalent of an online journal or diary (Schmidt and Ralph, 2011). Digital images and music entries are called blog posts, posted on the World Wide Web by the authors, called bloggers. The conversation begins when someone publishes and posts an article, which is followed by readers’ comments (Thevenot, 2007). Bloggers also use shorter blog postings (140 characters or less), called micro-blogs or tweets, published on the Web via Twitter, for example. Vlogs, video blogs, or video Web logs, combine video and user-generated, television-like, content (Morrissey, 2006; Ojeda-Zapata, 2006). Several popular video bloggers use the site,YouTube.

A podcast is defined as “a digital recording of a radio broadcast or similar programme, made available on the Internet for downloading to a personal audio player” (Bierma, 2005, p. 1). The term originated as a play on the word, broadcast, and the name of Apple’s handheld digital music player, the iPod. A wiki is a Web site that allows users to add, delete, or change content on the site using their own Web browser, allowing for collaborative authoring (Tulgan, 2007). The best example of a wiki is the popular Wikipedia, a free encyclopedia in many languages that anyone can edit (techterms.com).

Additionally, social network sites are alternative communication tools that support relationships and activities to enrich users’ experiences (Palmer and Koenig-Lewis, 2009). They attract demographically distinct groups of users on professionally-managed digital communities via Web sites, such as Facebook, LinkedIn, Plaxo, and Ning. Facebook exceeded 500 million users globally in 2010 (Curran and Lennon, 2011), making it the world’s most popular social network (Kunz, Hackworth, Osborne, and High, 2011; Schmidt and Ralph, 2011). Furthermore, they allow members to associate, form sub-communities and relationships, exchange ideas, or share data, photos, and music (Hawn, 2009). As a result, the traditional communications model of one-to-one communication, via the telephone, for example, is being replaced to some degree by a one-to-many model, via a blog post, for example, or by a many-to-many model, via a Facebook wall post, for example (Hawn, 2009).

Organizational Uses of Social Media

Social media tools have already been used in multiple ways in various venues. Broadly, they allow for enhancing consumer dialogue and personalization, potentially building brand equity and developing relationship marketing (Saperstein and Hastings, 2010). The blogs, user groups, and social network conversations become one, large “focus group” of thousands (Saperstein and Hastings, 2010, p.1). These comments are in many ways more candid than the focus group format since the conversations are not moderated. User community sites and blogs may provide valuable user experience feedback and may also build effective viral campaigns for products (Marken, 2009). Moreover, the comments may have implications for sales, product development and customer service. For instance, a product feature that consumers are discussing via social media may need more emphasis in the organization’s messages; the associated keyword can be added for online searches and subsequent purchases.

Marketers of new products and services should use social media as a component in their marketing communications strategy. Social media should be integrated into the traditional media mix; it should not be used in isolation. Furthermore, social media potentially connects all marketing activity. It requires collaboration across functionalities, including those with social media expertise in each department. These efforts should be organized in an ongoing committee or council at the very least. Moreover, a system of measuring effectiveness should be implemented early. Social media can be measured in the same way as traditional success measures for media. In other words, established metrics can be used to assess return on investment (ROI) (Howell, 2010).

More specifically, social media tools have been considered for use within an organization’s internal and external communication strategy. Many intranets have implemented Web 2.0 features, such as blogs and business-related wikis. Video is used for training and corporate communication, but some organizations, including American Electric Power, have set up “a television studio for intranet productions, offering employees streaming video and live webcasts” (Hathi, 2007, p. 9).

However, the case for the implementation of social media in organizations is still unclear for most communicators (“Communicators Remain Unclear,” 2010). Even though most CEOs belong to older generations, many note that although social media can increase the level of personalization, technology is limited and cannot replace people in a room together (Tulgan, 2007; Hathi, 2007/2008). Yet, improvements have been made in the use of internal and external communications in organizations, and specifically, marketing and advertising, recruitment, and customer services. Social media tools have also been proposed in organizations as communication support at times of crisis. The distributed nature and inherent spontaneity of social media is perfect for unpredictable situations (Semple, 2009).

Along with electronic health records (EHRs), social media tools and other forms of information technology (IT) are becoming more accepted in their use in the health care sector, in which chronically ill can engage in self-management. Patients find support from those who care and follow them on Twitter. Social media doesn’t substitute for one-to-one encounters with health care providers, but according to Hawn (2009), it enhances the doctor-patient relationship. However, with these benefits come legal concerns relating to patient privacy. Additionally, independent practitioners or small group practices don’t have the time or money to explore the use of social media in their respective practices (Hawn, 2009).

Why Companies Target Consumers via Social Media

The number of consumers using social media has doubled since 2008 and users have gotten older (Madden, 2010, Rainie et al., 2011). One in four online mature consumers is engaged in the social media (Madden, 2010). So, firms relish the idea of their product or service being center-stage in an online community and they have designed their own blogs and forums with this in mind. Potentially, Web 2.0 allows companies to become more closely tied to their customers, by hosting or sponsoring communities and providing content to these communities in the form of information or entertainment.

In turn, companies may observe and collect information about their customers (Palmer and Koenig-Lewis, 2009). Many social network sites allow users to personalize preferences, therefore providing marketers with consumer segments (Wright et al., 2010). Additionally, there is evidence in the service sector that consumers prefer to base their decision on a service provider using information from friends and other personal contacts than a company’s traditional promotion mix elements of advertising, personal selling, and sales promotion (Palmer and Koenig-Lewis, 2009). Social media can facilitate positive word-of-mouth, which may help solidify the purchase decision.

There are more reasons to become involved in social media communities. First, social media is dominated by early adopters, although Marken (2009) provided no empirical support for this statement. Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations model (1962) has developed the belief that individuals differ in their time of adoption of new products. Rogers described five adopter groups: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards. The innovative firm should research the characteristics of innovators and early adopters and direct their marketing efforts toward those groups (Rosen et al., 1998). Innovators and early adopters are extremely important groups that are targeted at the beginning of the adoption process of new products and services.

Innovators are pivotal in maintaining a positive sales volume for the organization and may even erect barriers of entry toward other firms. They spread positive word-of-mouth to non-innovators and thus assist in the promotion of new products to non-innovators (Phau and Lo, 2004). In sum, it is very desirable to communicate with innovators, i.e., those who want to be the first to try new products and services, and this group is prevalent in online communities. This group will, in turn, influence later adopters in the adoption process. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Social media consumers have greater innovativeness than non-social media consumers.

Perceived risk is “a function of the unexpected results of adoption and an outcome that deviates from expectation” (Hirunyawipada and Paswan, 2006, p. 187). Some consumers tend to perceive high degrees of risk in some consumption situations and other consumers tend to perceive little risk. Innovators are risk takers. They are willing to take risks in purchasing products and services that are new to the marketplace. The term, venturesome, has been traditionally used to describe innovators, who are willing to accept the risk of purchasing new products and services (Rogers, 1962). Therefore, the second hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Social media consumers are less risk averse than non-social media consumers.

When consumers are satisfied with a brand, over time they may develop brand loyalty. Brand loyal consumers engage in positive word-of-mouth and repeat purchases, which results in increased revenue for the organization (Lin, 2011). In social media, the concept of “brand communities” has received considerable attention (Palmer and Koenig-Lewis, 2009). It is here that consumers become interdependent due to collective identity, shared rituals, and moral responsibility to members (Muniz and O’Guinn, 2001). Over time, a brand community may facilitate the history and culture of the brand, ultimately fostering loyalty to the brand. Thus, as an exclusive characteristic of the social media, the brand community may be a unique way that organizations may enhance brand loyalty of their products and/or services. However, it is unclear that this potential has been reached via the brand community. Therefore, the third hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Social media consumers are more brand loyal than non-social media consumers.

Satisfaction has been traditionally associated with the Disconfirmation of Expectations Theory, which is based on the assumption that consumers compare the result with their expectations. A result greater than expectations, or a positive disconfirmation, yields satisfaction, whereas a result less than expectations, or a negative disconfirmation, yields dissatisfaction (Castaneda et al., 2007). Those consumers that use one or more forms of social media, a technology that is entirely voluntary, are intuitively more satisfied with the Internet than those consumers who use the Internet but do not use social media. Social media consumers potentially have more Internet options to have a more enjoyable and enriched experience online than those who do not use social media. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Social media consumers are more satisfied with the Internet than non-social media consumers.

Methodology

Respondents

The study was conducted in 2010 and again in 2012. The studies samples were regional samples from the southeastern United States. The respondents consisted of people who had been contacted by upper level undergraduate marketing students from a medium-sized university who were trained in data collection procedures. This approach, a variation of the convenience sampling method, has been successfully used in previous research (e.g., Arnold and Reynolds 2003; Bitner et al. 1990; Jones and Reynolds, 2006). A pretest was conducted in the first study with the students who were going to administer the questionnaire. The student group was representative of the characteristics of the final sample: mostly traditional students (18-23 year olds, members of Generation Y) and some non-traditional students. A few minor revisions were made to the questionnaire as a result of the pretest.

Next, approximately 40 student interviewers in each study were instructed to recruit respondents who had registered for social media (as social media sample) to complete one version of the questionnaire. The same interviewers also recruited respondents who had not registered for social media (as non-social media sample) to complete a second version of the questionnaire. The questionnaires were identical for the two groups with the exception of the statements to assess the uses of social media, which was only administered to social media users. Respondents completed a hard copy of the questionnaire. To ensure accurate responses, the respondents were promised complete confidentiality.

With the exception of the pretest conducted in the 2010 study, all administration procedures were identical in 2010 and 2012. There were 293 usable questionnaires in the social media sample of the 2012 study (222 in the 2010 study) and 278 usable questionnaires in the non-social media sample of the 2012 study (216 in the 2010 study) for a total sample of 571 in the 2012 study (438 in the 2010 study). This convenience sample was deemed appropriate because the purpose of the study was not to provide point estimates of the variables but to test the relationships among them (Calder et al., 1981).

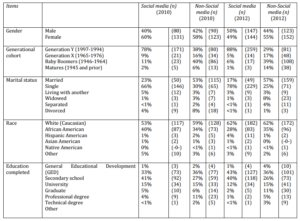

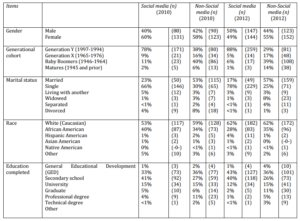

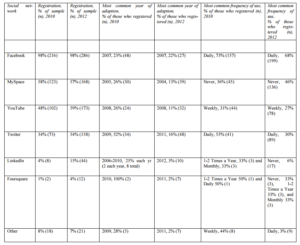

The social media sample consisted of 50.2% male (49.1% female) compared to 40.2% male (59.8% female) in the 2010 study. The greatest representation by a generational cohort was Generation Y at 88.4% (77.7% in the 2010 study). Online social network sites are viewed by younger age groups as an integral part of their life (Palmer and Koenig-Lewis, 2009). Over 78% of the sample was single (over 65% in the 2010 study). The majority of the social media sample (62.1%, 52.7% in the 2010 study) consisted of [white] Caucasians. Over 43% had completed secondary school compared to over 40% having completed a university degree in the 2010 study. Over 66% of the sample were students compared to almost 50% in the 2010 study. Approximately 49% of the social media sample had an income in the $0-10,000 range compared to about 45% in the 2010 study.

The non-social media sample for the study consisted of 44.2% male (54.7% female) compared to 42.3% male (57.7% female) in the 2010 study. The most represented generational cohort was Baby Boomers (38.8% compared to 40.4% in the 2010 study) followed by Generation Y (29.1% versus 37.6% in the 2010 study). In contrast to the social media sample, about 17% (30% in the 2010 study) of the non-social media sample was single and the majority of the non-social media sample (61.9% versus 59.3% in the 2010 study) consisted of [white] Caucasians. Over 36% (compared to over 35% in the 2010 study) had at least completed a secondary school degree and 26.3% (27.4% in the 2010 study) of the non-social media sample completed an undergraduate degree. Over half of the non-social media sample was employed by an organization (51.4%, compared to 50.9% in the 2010 study). The largest income category was $30,001-50,000 (24.8%) compared to $70,000 and above (23.6%) and $30,001-50,000 (23.1%) for the 2010 study.

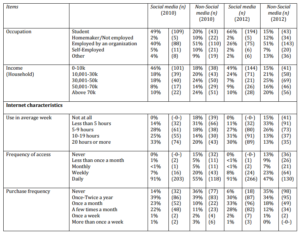

As expected, the most frequent use of the Internet for the social media group was ten to 19 hours per week (31% versus five to nine hours per week or 27.5% in the 2010 study) whereas the most frequent use of the Internet for the non-social media group was less than five hours per week (32.7% versus 30.6% in the 2010 study). Interestingly, the majority in both groups accessed the Internet daily in both studies. This was the most frequent response for the social media group (90.7% versus 91.4% in the 2010 study) and the non-social media group (46.8% versus 54.9% in the 2010 study). Internet purchase frequency was greatest at once a month (32.8%) for the social media group and never (35.3%, 34.2% for once/twice a year) for the non-social media group. This is in contrast to the 2010 study in which each group selected the response, once/twice a year with the greatest frequency of their purchase occasions via the Internet (38.7% for social media and 38.6% for non-social media). Complete information on the sample description is in Table.

Table 1: Descriptive Information of Sample

Table 1: Descriptive Information of Sample (Continued)

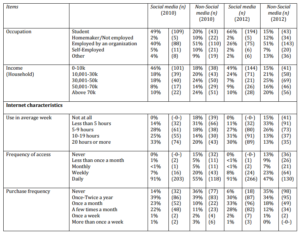

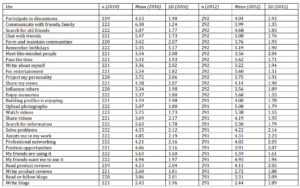

Social media consumers were asked to indi-cate if they had registered for any of the pop-ular social media (Facebook, MySpace, You-Tube, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Foursquare), with the final choice, “Other, please specify.” Additionally, they were asked to indicate the year of registration and frequency of use on a five-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = daily. The results are shown in Table 2. Please note that, while Facebook and MySpace remained practically unchanged in terms of the percen-tage of sample registered for these social media, YouTube, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Foursquare saw dramatic increases in these percentages. Although the most common year of adoption was 2008 for YouTube, the other three social media experienced their most common year of registration in 2011 or 2012. However, Facebook and MySpace still hold the largest percentages of those registered for social media.

Table 2: Social Networks: Registration, Year of Adoption and Frequency of Use

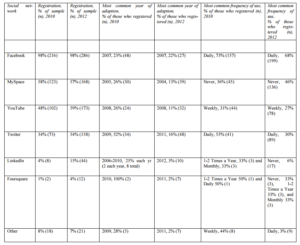

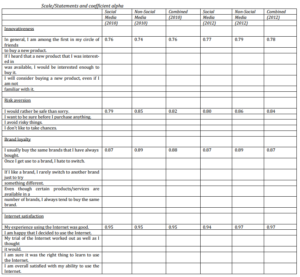

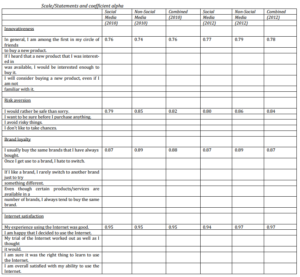

The uses of social media were listed, each followed by a seven-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, including an “other” category (n=87). The results are shown in Table 3. Those uses with a 5.50 mean or greater included the following: “communicate with friends, family” (5.99 versus 6.30 in the 2010 study), “pass the time” (5.62 versus 5.41 in the 2010 study), “write about myself” (5.60 versus 5.54 in the 2010 study), “enjoy memories” (5.60 versus 5.37 in the 2010 study), and “my friends are using it” (5.59 versus 5.63 in the 2010 study). “Search for information” had a mean of 5.60 in the 2010 study in contrast to a 5.30 mean in the 2012 data.

Table 3: Uses of Social Media

Measures

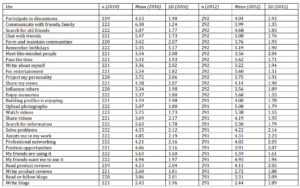

All scales are well-established and have been used in previous research. Per Goldsmith (2001, p. 150), the three-item, domain specific innovativeness scale “can be used in a variety of research settings and has proved to be valid and reliable across different product domains and cultures.” The risk aversion scale was measured by a modified four-item scale used by Donthu and Gilliland (1996). Loyalty to the product/brand was measured using the four-item scale developed and used by Lichtenstein, Netemeyer and Burton (1990) and Raju (1980). Satisfaction for Internet use for both groups was assessed using a five-item scale developed and used by Oliver (1980). The scales were modified to fit the purposes of the study. All items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree,” in which the rating, 4, was for respondents who felt neutral.

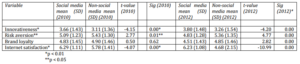

Reliability coefficients were computed for each of the scales. Coefficient alphas were reported for the social media group and the non-social media group as well as the total sample. All alpha values were above the 0.70 value recommended by Nunnally (1978). Table 4 presents the items used in the current research.

Table 4: Reliability Coefficients

Analysis and Results

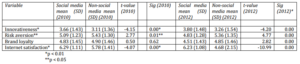

Independent-samples t-tests were used to test the hypotheses; the results are summarized in Table 5. In the 2010 analysis, the results supported the first hypothesis that members of social media respondents have greater innovativeness than non-social media respondents (p < 0.01). The second hypothesis was also supported that social media respondents are less risk averse than non-social media respondents (p < 0.05). There was no support for the third hypothesis that social media respondents have greater brand loyalty than non-social media respondents. The fourth hypothesis, that social media respondents have more satisfaction toward the Internet than non-social media respondents, was supported (p < 0.01).

In the 2012 analysis, all hypotheses were significant at the 0.00 level. The third hypothesis that social media respondents have greater brand loyalty than non-social media respondents was significant but in the opposite direction than was hypothesized.

Table 5: Differences between Social Media and Non-Social Media

Conclusion

This study examined and compared social media and non-social media consumers. First, demographic profiles were provided for each group. The social media user demographic profile revealed that this group was dominated by Generation Y. This finding was expected, since “younger consumers have typically been early adopters of new technologies” (Roche and Williams, 2006, p. 2A) and 86% of young adults ages 18-29 report that they use social networking sites, making this group the heaviest users as Madden (2010) concurs.

Second, the two groups were compared in terms of their innovativeness, risk aversion, brand loyalty, and Internet satisfaction. All differences were significant except for brand loyalty in the 2010 analysis. This finding adds to the often-heard contention, although not universal (Dekimpe et al., 1997), that brand loyalty is in decline and that consumers are more versatile and less loyal than they have ever been (“The Roots of Brand Loyalty,” 2005). Saxton (2005) notes that brand loyalty is less evident among young people, due to more freedom to choose. Nevertheless, Fabiano (2010) states that brands integrating social media into their marketing communications are those that gain consumer interest and loyalty. Based on the 2010 analysis, social media consumers have greater innovativeness, less risk aversion, and more Internet satisfaction than non-social media consumers.

In contrast, results were significant in the 2012 analysis for brand loyalty but in the opposite direction than was hypothesized. In other words, there was support that non-social media consumers are more brand loyal than social media consumers. Since the majority of the non-social media group was older (Baby Boomers) than the majority of the social media group (Generation Y), based on age, this finding concurs with the traditional perspective that older consumers are more brand loyal than younger generational cohorts (Anderson and Sharp, 2010; Anonymous, 2007a; Davies, 2007; Kim, 1987).

Managerial Implications and Limitations

The results are significant for marketers utilizing social media, but especially significant for the marketer of new products and services who wishes to target innovators and early adopters. Innovators and early adopters seek products and services that are the latest releases to the marketplace, and therefore exhibit a relatively high degree of innovativeness. They are also risk takers, since these innovations have not yet been adopted by most consumers. Due to a significant presence of innovators and early adopters on the social media, marketers of innovations may consider leveraging this new communication to introduce their products and services. Doing so may yield a competitive advantage over less astute marketers of innovations. Marketers should feel encouraged to take advantage of social media opportunities, due to, in part, the Internet satisfaction experienced by social media users.

Additionally, marketers of new products and services are faced with the challenge that a high percentage of new products fail during their introduction. Since the introduction stage of the product life cycle is the riskiest stage in the life of a product, it is important to attempt to reduce this risk. Social media can help to reduce this risk, since consumers engaged in social were found to be less risk averse. They are increasingly using social media to share their feelings about both new and existing products, whether these feelings are likes and compliments, or dislikes and complaints. Marketers of innovations who implement social media may benefit from nearly immediate feedback before, during, and after a new product launch. Customer feedback via social media can address this issue at all phases of the new product launch. Pre-launch is a time when consumers can assist new product marketers with testing, for example, the test marketing of messages. During the launch, consumers may potentially be the greatest advocates of the new product. And finally, the post-launch is a time to keep consumers engaged so that they may positively influence others in the purchase decision process (Anonymous, 2011).

This study has potential limitations and has provided possible directions for future research. First, the respondents comprised a regional sample. Future research may wish to determine if the results may be replicated with a broader, national sample. Second, the study examined variables with implications for innovators and early adopters. Future research may examine other variables that are related to the study of this important media form. For example, how social media is used by particular generational cohorts may be the focus of the analysis. There may be ways in which social media use could be increased in cohorts, such as Baby Boomers and Matures, that are currently not using the communication as much as other cohorts, such as Generation Y.

Third, the scale assessing brand loyalty could be updated to include the organization as well as a product or service. What constitutes a brand has been expanded to include the organization and this expansion is evident in social media via the concept of brand communities. Finally, the research examined the construct, risk aversion. Future research may wish to explore aspects of risk that are indigenous to social media, particularly security risk. Lack of security on social media sites has resulted in scams and account hacking, in which site accounts have been used for sending malicious messages or for identity fraud. Future research could examine the difference in risk perception toward social-media use between the two groups of consumers.

This research was funded by a grant from the Rea and Lillian Steele Foundation.

References

Anderson, K. & Sharp, B. (2010). “Do Growing Brands Win Younger Consumers?,” The Journal of the Market Research Society, 54 (4), 433.

Publisher

Anonymous (2007a). ‘Brand Loyalty: Does It Deepen with Age?,’ Selling to Seniors, July, 1.

Anonymous (2011). “BzzAgent Unveils Guidance for Using Social Media to Launch New Products,” Business Wire, March 2011, 1.

Publisher

Arnold, M. J. & Reynolds, K. E. (2003). “Hedonic Shopping Motivations,” Journal of Retailing, 108 (2), 1-20.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Baker, B. (2009). ‘Your Customer is Talking — To Everyone; Social Media is the New Channel for Customer Connection,’Information Management, 19 (4), 20.

Google Scholar

Bierma, N. (2005). The Chicago Tribune at Random Column: “‘Podcast’ is Lexicon Word of The Year,” Knight Ridder Tribune Business News, December 28, 1.

Publisher

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H. & Tetrault, M. S. (1990). “The Service Encounter: Diagnosing Favorable and Unfavorable Incidents,” Journal of Marketing, 54 (January), 71-84.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Calder, B. J., Phillips, L. W. & Tybout, A. M. (1981). “Designing Research for Application,” Journal of Consumer Research, 8 (2), 197-207.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Castaneda, J. A., Frias, D. M. & Rodriguez, M. A. (2007). “The Influence of the Internet on Destination Satisfaction,”Internet Research, 17 (4), 402-20.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Curran, J. M. & Lennon, R. (2011). “Participating in the Conversation: Exploring Usage of Social Media Networking Sites,” Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 15 (1), 21-38.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Davies, B. (2007). ‘Men’s Grooming: Worth the Hype?,’ Global Cosmetic Industry, 175 (12), 64-67.

Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Dekimpe, M. G., Steenkamp, J.- B. E. M., Mellens, M. & Abeele, P. V. (1997). “Decline and Variability in Brand Loyalty,”International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14 (5), 405-20.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Donthu, N. & Gilliland, D. (1996). “Observations: The Infomercial Shopper,” Journal of Advertising Research, 36 (2), 69-77.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Fabiano, K. (2010). “Using Social Media to Inspire Brand Loyalty,” Dealerscope, 52 (1), 40.

Publisher

Goldsmith, R. E. (2001). “Using the Domain Specific Innovativeness Scale to Identify Innovative Internet Consumers,”Internet Research, 11 (2), 149-58.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Goldsmith, R. E. & Stith, M. T. (1990). ‘The Social Values of Fashion Innovators,’ Journal of Applied Business, 9, 10-15.

Hastings, H. & Saperstein, J. (2010). “How Social Media can be Used to Dialogue With the Customer,” Ivey Business Journal Online, (January/February), 1.

Publisher

Hathi, S. (2007). “Intranets Embrace Social Media,” Strategic Communication Management, 11 (2), 9.

Publisher

Hathi, S. (2007/2008). ‘CEOs Stand Divided on Social Media,’ Strategic Communication Management, 12 (1), 9.

Hathi, S. (2009). ‘Communicators Remain Unclear on Business Case for Social Media,’ Strategic Communication Management, 14 (1), 9.

Google Scholar

Hawn, C. (2009). “Take Two Aspirin and Tweet Me in the Morning: How Twitter, Facebook, and Other Social Media are Reshaping Health Care,” Health Affairs, 28 (2), 361-68.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Hirunyawipada, T. & Paswan, A. K. (2006). “Consumer Innovativeness and Perceived Risk: Implications for High Technology Product Adoption,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23 (4), 182-98.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Howell, K. (2010). “Digital Strategy: Social Media. Are You Still Ignoring It?,” Marketing Week, September 16, 30.

Publisher

Jones, M. A. & Reynolds, K. E. (2006). “The Role of Retailer Interest on Shopping Behaviour,” Journal of Retailing, 82 (2), 115-126.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kim, K. H. (1987). ‘Consumer Attributes of Brand Loyalty for Low-Involvement Products,’ United States International University, dissertation.

Google Scholar

Kunz, M. B., Hackworth, B., Osborne, P. & High, J. D. (2011). “Fans, Friends, and Followers: Social Media in the Retailers’ Marketing Mix,” Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 12 (3), 61-68.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lichtenstein, D. R., Netemeyer, R. D. & Burton, S. (1990). “Distinguishing Coupon Proneness From Value Consciousness: An Acquisition-Transaction Utility Theory Perspective,” Journal of Marketing, 54 (July), 54-67.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lin, Y. H. (2011). ‘The Impact of Service Encounters on Behavioral Intentions to Online Hotel Reservations,’ The Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 15 (2), 262-74.

Madden, M. (2010). ‘Older Adults and Social Media: Social Networking Use among those Ages 50 and Older Nearly Doubled over the Past Year,’ Pew Internet and American Life Project (August 27).

Google Scholar

Marken, G. A. (2009). ‘Social Media. . . The Hunted Can Become the Hunter,’ Public Relations Quarterly, 52 (4), 9-12.

Morrissey, B. (2006). “Coke’s World Cup Push: Vlog is It,” Adweek, 27 (25), 20.

Publisher

Muniz, A. M. O. & O’Guinn, T. C. (2001). “Brand Community,” Journal of Consumer Research, 27 (4), 412-32.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory, New York: McGraw Hill.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Ojed-Zapata, J. (2006). “For Great TV, Tune in to the Web,” Knight Ridder Tribune Business News, November 26, 1.

Publisher

Oliver, R. L. (1980). “A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction,” Journal of Marketing Research, 17 (4), 460-69.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Palmer, A. & Koenig-Lewis, N. (2009). “An Experiential, Social Network-Based Approach to Direct Marketing,” Direct Marketing: An International Journal, 3 (3), 162-76.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Phau, I. & Lo, C. C. (2004). “Profiling Fashion Innovators: A Study of Self-Concept, Impulse Buying and Internet Purchase Intent,” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 8 (4), 399-411.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Rainie, L., Purcell, K., Goulet, L. S. & Hampton, K. N. (2011). ‘Social Networking Sites and Our Lives,’ Pew Internet and American Life Project (June 16).

Google Scholar

Raju, P. S. (1980). “Optimum Stimulation Level: Its Relationship to Personality, Demographics, and Exploratory Behavior,” Journal of Consumer Research, 7 (December), 272-282.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Roche, T. & Williams, S. (2006). “The Fast and Fascinating Rise of Generation Y,” American Banker, April 18, 2A.

Publisher

Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of Innovations, New York: The Free Press.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rosen, D. E., Schroeder, J. E. & Purinton, E. F. (1998). “Marketing High Tech Products: Lessons in Customer Focus From the Marketplace,” Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1998 (6), 1-17.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Rudnick, M. & Wyatt, W. (2007b). “Integrate New Technology and Social Media into HR Processes,” Strategic HR Review, 6 (2), 5.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Saxton, G. (2005). “Collections of Cool,” Young Consumers, 6 (2), 18-27.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Schmidt, S. M. P. & Ralph, D. L. (2011). ‘Social Media: More Available Marketing Tools,’ The Business Review, Cambridge, 18 (2), 37-43.

Semple, E. (2009). “Update Your Crisis Comms Plan with Social Media,” Strategic Communication Management, 13 (5), 7.

Publisher

Techterms. The Tech Terms Computer Dictionary, Obtained through the Internet: http://www.techterms.com/, [accessed 8/20/2010].

Publisher

Thevenot, G. (2007). “Blogging as a Social Media,” Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7 (3/4), 287-89.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Tulgan, B. (2007). “Finding Roles for Social-Media Tools in HR,” Strategic HR Review, 6 (2), 3.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Wright, E., Khanfar, N. M., Harrington, C. & Kizer, L. E. (2010). “The Lasting Effects of Social Media Trends on Advertising,” Journal of Business & Economics Research, 8 (11), 73-80.

Publisher – Google Scholar