Introduction

Territories compete with each other to attract visitors, residents and investors. As Kavaratzis and Ashworth (2008, p. 151) put it, they have “to differentiate themselves from each other in order to assert their individuality and distinctive characteristics in pursuit of various economic, political or socio-psychological objectives”. Considering the visitors segment, a touristic destination is not just a set of tangible resources. As Cooper and Hall (2008, p. 219) state, it must be regarded as “the physical space where tourism takes place, where communities live and work and is imbued with symbols and images of culture and history”. It is necessary to address not only the benefits and well-being of tourists but also that of the locals (Brohman, 1996). They are one of the main elements in the process of building a territorial brand (Braun, Kavaratzis & Zenker, 2013; Freire, 2009; García, Gómez & Molina, 2012; Houdson, Cárdenas, Meng& Thal, 2017 and Sousa & Silva, 2019). Therefore, it is essential to sensitize the population about the value of their region, their habits and the value of their regional products.

This valorisation of regional assets and products is not a simple task, especially in rural locations (Brohman, 1996; Middleton & Hawkins, 1998 and Oliveira, 2015). Marketing efforts should not only focus on attracting tourists, but also on local development (Buhalis, 2000 and Papadopoulos, 2004). Consequently, the marketing strategy must be aligned with the characteristics and complexities of the region, and should not be out of step with its history, its values and culture. Although rurality is fundamental for differentiation, it is difficult to pass on this concept to locals when they are used to seeing their work and handicrafts being undervalued. It tends to be difficult to make them understand the value that these products have today and the unique experiences that tourists feel when watching and experiencing ancient modes of production. Community involvement in planning and development is therefore a critical factor for tourism sustainability in that destination (Choo, Park & Petrick, 2011; Cook, 1982; Freire, 2009; Lichrou, O’Malley & Patterson, 2010 and Murphy, 1985).

“Territorial marketing is a fundamental tool in the promotion of places, one that must be present in the strategies of local government representatives, helping and promoting a sustainable economic and social development of the regions”. As Haywood (1990) points out, tourism is essentially a local community industry. Destinations that use and adapt their resources solely to meet the needs of tourists, may undermine the interests and needs of the local community, thereby destroying what initially made them attractive and distinctive for tourists. The local community is a vital part of the experience that tourists want to have at the destination (Aitken & Campelo, 2011; Freire, 2009 and Nuryanti, 1996), being one of the most important elements in the process of creating their own image. Thus, it is essential that their needs are met and that the tourism development process generates involvement and identification with local populations (Choo et al., 2011).

Although the relevance of locals to regional marketing and branding has been recognized by several authors (cf. Braun et al., 2013; Freire, 2009 and García et al., 2012), the analysis of their role in territorial branding has been neglected (Vuignier, 2015). In fact, there has not been a concrete model yet that allows inserting their roles in the territorial management in a dynamic and interactive way. In this paper, taking advantage of all the existing knowledge about the relevance of the local to the territorial brand and applying the concepts of co-production and co-consumption (Hankison, 2007), to which co-communication is added, an operational model has been developed that places the locals as a central element in the entire regional branding strategy.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 offers a comprehensive overview of the theoretical background. Firstly, the local community is contextualized as one of the most relevant elements in the construction of territorial offer. Secondly, it addresses the construction of the territorial offer, highlighting the role of locals for their production, communication and consumption. Section 3 presents the model developed with the aim of making locals’ participation operational. Finally, section 4 summarizes the main contributions of the paper and concludes with limitations and suggestions for further research.

Conceptual Background

Marketing was initially applied to territories based on a transactional perspective. Its main focus was to attract customers to an existing territory – whether country, region, or city. From this point of view, communication assumed a central role in territorial marketing. However, the way territorial marketing is considered, has evolved due to an increasing competition among territories along with the evolution of marketing as discipline (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, 2008). For this reason, besides contributing to the communication and sale of a territorial offer, marketing today assumes a fundamental role in the development of such offer, redefining the territory and its future evolution.

Locals

The local community of a territory is one of the most important elements in the construction of the territorial offer, since it is at the same time the producer and consumer of such offer (Hankison, 2007). For this involvement to take place, it is necessary to provide all actors with the right information about the characteristics of the development process to be implemented, the necessary contribution from each one and the benefits they can have from this process (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, 2008). This information is essential to get locals identified with the development process as they do not identify with something they do not know or foresee any benefit for. Identification with the development process is a necessary condition to generate involvement in this process. Once involved, locals tend to act as true promoters of the region by conveying messages consistent and appropriate to the characteristics of the offer, in contact with other audiences (García et al., 2012).

Depending on the characteristics of the territory, local community can vary in size, diversity, dispersion, as well as interests. This heterogeneity makes the alignment of the local community, with the values and the territorial vision, a complex driving force.

For this reason, residents should be the central focus of tourism managers’ attention to ensure that they are proud and satisfied with their territory (Wang & Xu, 2015). Any territorial marketing strategy should be appropriate to the characteristics and complexities associated with this community, and should not be out of step with its history and values (Freire, 2009). It is especially important that the locals are called upon to comment on the territorial marketing strategy, because the offer is created and delivered daily based on their activities and behaviour (Kavaratzis, 2017).

In sum, any territorial offer encompasses not only tangible but also intangible elements. All territories have a particular history and a cultural heritage, and share a number of values and traditions. Locals proudly affirm their origin, which is not always the case with companies that sometimes, due to the stereotypes associated with a certain region, hide the origin of their products through names that refer to other countries.

Territorial Offer

The construction of the territorial offer presents a clear reduction in the degrees of freedom compared to what happens in the production of products and services, which makes the ability to influence one of the key competences of territorial marketing. In fact, a territorial marketing strategy is largely about influencing a wide range of actors to build and communicate a consistent and integrated territorial offer.

Territories are made up of a wide web of diversified actors. The consumption of this offer occurs through the interaction among different audiences, and its communication depends on the actions of multiple agents. For this reason, it is easy to argue that the territorial offer is co-produced, co-communicated and co-consumed (Hankison, 2007).

Co-Production

The territorial offer may include elements that stand out from the others. But even these key elements, such as a stunning beach, a dynamic industrial park or a university, require the action of other components of the offer. No territory involves a single product only, but a large portfolio of interdependent parties influencing the value of each other.

A territory, depending on its size, may include thousands of public and private entities. Each of them, acting autonomously and individually, contributes to the production of the territorial offer. Hospitals, police stations, hotels, universities, theatres, museums and restaurants produce part of the territorial offer. All residents, whether integrated into these organizations or not, also contribute to the territorial offer through the way they behave and their friendliness or professionalism.

In short, one of the most important tasks of any organization responsible for marketing a territory will be to make all these entities aware of their relevance to the territorial offer, making them clearly understand that they are co-producers of that offer. Subsequently, this whole community should participate in the definition of the territorial values and vision in order to identify them with these structuring elements. Only in this way can the territory as a whole be able to convey consistent messages.

Co-Communication

Everything that happens territorially (e.g. local production, local brands, security, economic performance and climate change) or carried out by entities related to the territory (such as politicians and public figures) on a daily basis, communicates the characteristics of the territorial offer, thus having the potential to influence its image and attractiveness. At the same time, some of these entities themselves actively communicate messages about the territory. Hotels communicate characteristics of the territory to which they are related, just as food, technological or fashion products may communicate territorial characteristics that enrich their value proposition.

As Sousa and Rocha (2019, p. 189) state, “territorial marketing is a fundamental tool in the promotion of places; one that must be present in the strategies of local government representatives, helping and promoting a sustainable economic and social development of the regions”. However, this dependence on multiple actors makes territorial communication dependent on any individual action. In fact, Hakala and Öztürk (2013, p. 182) argue that “even one person can make a difference, either by starting the branding process or repositioning the city”. This circumstance does not diminish the relevance of communication actions controlled by the territory. On the contrary, this communication should be reinforced and directed not only abroad but also to all internal agents who communicate the territorial offer, through their behaviours and activities. Only by being aware of how the territory intends to communicate externally and the image it intends to build, can local territorial agents behave in a manner that coincides with that intended image (García et al., 2012). Thus, one of the most important measures of territorial image construction involves communication with territorial agents in order to influence their behaviour.

In short, like other organizations, the territory has both controlled and uncontrolled sources of communication. However, the extent of uncontrolled sources is much more relevant here, because just as the territorial supply is co-produced by a multiplicity of entities, each of them may act through their behaviours and activities as a communication element of the territory.

Co-Consumption

The territorial offer made available by the territory is produced, as mentionedby multiple entities. This offer may include job opportunities, dream vacations, business opportunities, cultural activity, serenity, industrial infrastructures, skilled labour and safety that may meet the very different needs of different target audiences. In addition to having to deal with this heterogeneity of “producers” and target audiences, territorial management still faces another challenge; harmonizing consumption among these different audiences that happens simultaneously and in interaction.

A tourist in vacation enjoys the same infrastructure and services available to a resident and while the resident may want peace of mind, the tourist may want fun, making this interaction not compatible. On the other hand, the employees of a company view it as part of the territorial offer related to job opportunities. Meanwhile, the company in question perceives the employees as part of the territorial offer that allows it to use human resources appropriate to their needs. In this case there is also a simultaneous consumption of differentiated benefits from the territorial offer. Paradoxically, it is all these “customers” who build what the territory has to offer, to a large extent, through their consumption,

Model of Territorial Marketing

So far this model has focused on the most strategic elements of territorial marketing. These elements include defining the values of the territory that can generate the involvement of their community around a common vision. The definition of these elements is only part of a long journey that will later include the integration of diverse actions.

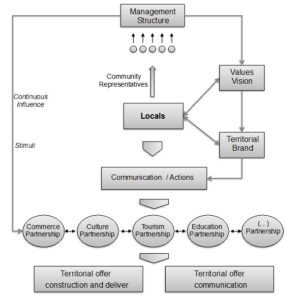

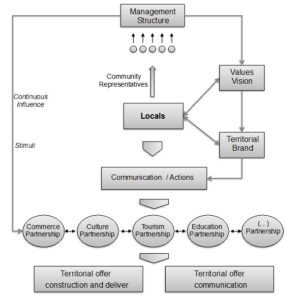

The complex features associated with the territories are very different, so there are no generic recipes of actions to implement in order to develop and enhance their offer. Nevertheless, some essential steps are referred to as the operationalization of a territorial marketing strategy (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: A Model for the Development of a Territorial Marketing Strategy

Management Structure

Considering the number of locals (that can vary from less than one hundred to many millions) it will be impossible to include them all in a direct way in the model. However, it is possible to identify among the locals, the ones that can represent the community in diverse areas related to its development. These community representatives have a critical role representing the locals in the territorial management structure (usually called DMO – Destination Management Organization) that is responsible for defining and implementing the marketing strategy (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, 2008).

This structure should lead the process of interaction with the multiple co-producing agents of the territorial offer and it should be strengthened with concrete powers of action and legitimized by society. It should include representative elements of the whole territorial community among its advisory members. The interconnection of this structure with the locals will also allow a greater identification with the values and territorial vision that may be defined.

The consistency required for territorial marketing is however a difficult task to achieve. Generally, much of the strategic orientation changes along with the changes of political executives. There is also a strong demand for actions that produce visible effects in a short period of time; usually within the four-year electoral period. These constraints contribute to the primacy of elements associated with communication and visual identity rather than the effective appreciation of the offer.

To avoid this bias in favour of dispersed short-term actions, the first step in adopting a territorial marketing strategy should be the definition of its most structuring elements; the values and the vision of the territory together with its brand (Erfgen, 2014). These elements will allow the territorial offer to be integrated in a consistent manner, aligning all subsequent actions and avoiding electoral influences. Due to their relevance in the territorial trajectory, these elements must be defined with a great involvement and identification of the local community.

Subsequently, a territorial brand able to translate these elements (values and territorial vision) should be created or reformulated. This brand, generating communication synergies and capturing the intangible heritage of the territorial offer, will enhance the actions, the value of the offer and the awareness associated with the territory. The locals are going to deliver the brand actions and communicate it actively on a daily basis. In short, more than being simple ‘brand ambassadors’, they are ‘brand makers.

Due to the multiplicity of competition in the most diverse areas (touristic, business, residential…), the territories need to create a unique category in the target audience that allows them to differentiate themselves. The sources of differentiation should be based on factors that are difficult to replicate, avoiding generic or easily appropriated categories from other territories. The intangible legacy of the territory, such as traditions, popular knowledge, culture and local brands with its uniqueness, is a guarantee of differentiation that must be taken into consideration in the territorial brand architecture (Anholt, 2007). At the same time, it allows leveraging endogenous elements associated with the territory as sources of competitiveness, which contributes to the sustainability of the territorial offer.

Given the diversity of the offer elements, one of the most common problems of territorial marketing is the transmission of messages with many appeals, making them easily confusing and/or inconsistent. Territories should not pretend to be everything, but turn out to be experts in some particular features. Thus, the message/promise associated with the territorial brand should be clear and differentiating. However, the existence of multiple target audiences, which in turn are interested in particular components of territorial supply, may make it necessary to convey specific messages. Using an analogy with the business domain, the territory can articulate an umbrella corporate brand with different product brands under that brand. The associated positioning of the territorial brand should serve as a unifying framework by which the territory intends to be recognized while acting as a territorial promise – that is, the brand is an element that fosters the identity of the place (Sousa, Casais & Pina, 2017). As mentioned above, it is essential that this positioning will be identified with the local community, as its realization depends greatly on its behaviour.

Communication

Once created, the territorial brand will also serve as an integrated communication platform, aimed at two generic types of audiences; the internal ones, who are already consumers of the territorial offer (residents, companies and locally-based organizations, who are simultaneously producers of their offer), and the external ones, who are mainly the target audiences to be conquered. For the former, the communication should be oriented to the involvement with the territory, while for the latter, it should mainly highlight the benefits of the territorial offer.

Just as product brands do not take repeat purchase for granted, trying to create a relationship based on reciprocal gain to build customer loyalty, so regions should not perceive internal audiences as conquered forever after their arrival/installation in the territory. An engagement process should be developed to reinforce the joint value of territorial offer and create intangible benefits that make it difficult to exchange the region for another alternative location. All actions should be leveraged in the brand in order to create awareness and value for it.

The way in which the locals interact with tourists, the manner in which the authorities help the companies solve their problems, even the menus in the restaurants or the shops windows are important sources of communication that should be influenced by the vision and territorial brand as much as possible.

Partnerships

No single organization can independently control the whole process of territorial offer development by itself. It is essential that the entity responsible for territorial marketing articulates and encourages networks of partners involving the main actors responsible for the various domains of territorial offer. These networks have an important role in the operationalization of the strategy because they allow the aggrupation of the locals under their field of interest or relevance, making the interaction and the delivery of an integrated and consistent offer easier. Each of these networks should be in close interaction with the DMO in order to develop the territorial offer regarding its field of activity.

Due to the interdependent character of territorial offer, interactions between complementary networks should also be promoted. In fact, the realization of an action, such as an event, implies the joint participation of several fields of activity; commerce, tourism and education. These partners act as representatives on the territorial structure ground. From their continuous interaction, much of the territory’s offers and communication will result. The DMO should therefore play a very intervening role in these networks of actors by continually influencing and stimulating its elements to enhance the offer value.

Conclusion

No territorial marketing strategy arises from a zero base – its development is always based on a pre-existing reality with its idiosyncrasies and own paths. One of the main specificities and simultaneous sources of territory differentiation is the local community. This community should have a central place in any territorial marketing strategy because it is the most decisive element for the construction of the territorial offer, for its communication and continuous dynamics, being simultaneously a consumer of that offer. Thus the specific features of any territory and its local community detract value from standard solutions replicated in a generic way and reinforce the importance of this community, which is crucial for territorial offer.

The model proposed in this article puts in evidence that local communities; the main element of territorial offer, should be placed in the central position of this strategy. In a domain where there are so many producers with independent but also complementary areas and interests, the most suitable way to operationalize the participation of the local community is through the creation of partnerships and groups of representatives that allow translating the interests and perspectives of each group into concrete actions strategically integrated. Due to the continuous emergence of new competitiveness factors, the current attractiveness or success of a territory is no guarantee of its good performance in the future. Take the case of Portugal that was one of the major world powers in the fifteenth century, or the decline of Detroit that, until a few years ago, was one of the most significant industrial centres in the USA. It is therefore necessary for the territory to be continually evaluated and to look for new forms of competitiveness and if necessary reinventing its essence.

This research should be viewed as an exploratory exercise translated into a model of analysis of a reality that involves multiple actors and reveals itself to be very complex. The proposed model therefore lacks an empirical validation that at first should occur through a qualitative methodology. Another line of future research will be to measure the relationship between local involvement and active participation in the construction and promotion of territorial offer. It will also be interesting to be able to quantify and relate the communication of a territory generated by official sources and by its residents.

To sum up, initially used in a more immediate and communicational perspective, territorial marketing is currently much more than a visual identity applied to a territory. It should now be perceived as a long-term process and a strategic tool for territorial development.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Aitken, R. & Campelo, A. (2011), “The Four Rs of Place Branding”,Journal of Marketing Management, 27(9-10), 913-933.

- Anholt, S. (2007)Competitive Identity. The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Braun, E., Kavaratzis, M. & Zenker, S. (2013), “My City – My Brand: The different roles of residents in place branding”,Journal of Place Management and Development, 6(1), 18-28.

- Brohman, J. (1996),“New Directions in Tourism for Third World Development”,Annals of Tourism Research, 23(1), 48-70.

- Buhalis, D. (2000),“Marketing the Competitive Destination of the Future”,Tourism Management, 21(1), 97-116.

- Choo, H., Park, S.-Y. & Petrick, J. (2011),“The Influence of the Resident’s Identification with a Tourism Destination Brand on Their Behavior”,Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 20(2), 198-216.

- Cook, K. (1982),“Guidelines for Socially Appropriate Tourism Development in British Columbia”,Journal of Travel Research, 21(1), 22-28.

- Cooper, C. & Hall, M. (2008),Contemporary Tourism: An International Approach, Oxford: Elsevier.

- Erfgen, S. (2014),“Let them do the work: A participatory place branding approach”,Journal of Place Management and Development, 7(3), 225-234.

- Freire, J. (2009), “Local People: A critical dimension for place brands”,The Journal of Brand Management, 16(7), 420-438.

- García, J., Gómez, M. & Molina, A. (2012),“A Destination-Branding Model: An empirical analysis based on stakeholders”,Tourism Management, 33(3), 646-661.

- Hakala, U. & Öztürk, S. (2013),“One person can make a difference – although branding a place is not a one-man show”,Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 9(3), 182-188.

- Hankison, G. (2007), “The Management of Destination Brands: Five guiding principles based on recent developments in corporate branding theory”,Brand Management, 14(3), 240-254.

- Haywood, M. (1990),“Revising and implementing the marketing concept as it applies to tourism”,Tourism Management, 3, 195-205.

- Hudson, S., Cárdenas, D., Meng, F.& Thal, K. (2017), “Building a place brand from the bottom up: A case study from the United States”, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 23(7), 365-377.

- Kavaratzis, M. (2017),“The Participatory Place Branding Process for Tourism: Linking Visitors and Residents Through the City Brand”, in N. Bellini & C. Pasquinelli (Eds.), Tourism in the City: Towards an Integrative Agenda on Urban Tourism (pp. 93-107). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kavaratzis, M. & Ashworth, G. (2008),“Place Marketing: How did we get here and where are we going?”,Journal of Place Management and Development, 1(2), 150-165.

- Lichrou, M., O’Malley, L. & Patterson, M. (2010),“Narratives of a Tourism Destination: Local particularities and their implications for place marketing and branding”,Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 6(2), 134-144.

- Middleton, V. & Hawkins, R. (1998),Sustainable Tourism – AMarketing Perspective, Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

- Murphy, P. (1985),Tourism: A Community Approach, New York: Methuen.

- Nuryanti, W. (1996),“Heritage and postmodern tourism”,Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2), 249-260.

- Oliveira, E. (2015),“Place branding in strategic spatial planning: A content analysis of development plans, strategic initiatives and policy documents for Portugal 2014-2020”,Journal of Place Management and Development, 8(1), 23-50.

- Papadopoulos, N. (2004),“Place Branding: Evolution, meaning and implications”,Place Branding, 1(1), 36-49.

- Sousa, B., Casais, B. & Pina, G. (2017), “The Influence of Territorial Branding on the Tourist Consumer Predisposition: The Cape Verde Case”, European Journal of Applied Business and Management, Special Issue, 324-335.

- Sousa, B. and Rocha, A. (2019), “The role of attachment in public management and place marketing contexts: A case study applied to Vila de Montalegre (Portugal)”, International Journal of Public Sector Performance Management, 5(2), 189-205.

- Sousa, B. and Silva, M. (2019), “Creative Tourism and Destination Marketing as a Safeguard of the Cultural Heritage of Regions: The Case of Sabugueiro Village”, Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Desenvolvimento Regional, 15(5), 78-92.

- Vuignier, R. (2015),“Cross-Border Place Branding: The Case of Geneva Highlighting Multidimensionality of Places and the Potential Role of Politico-Institutional Aspects”, in S. Zenker & P. Jacobsen (Eds.), Inter-Regional Place Branding: Best Practices, Challenges and Solutions (pp. 63-72), Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Wang, S. & Xu, H. (2015),“Influence of place-based senses of distinctiveness, continuity, self-esteem and self-efficacy on residents’ attitude towards tourism”,Tourism Management, 47, 241-250.