Introduction

The origins of participatory democracy can be traced back to Ancient Greek philosophers like Aristotle, who believed that citizen participation in government promotes the common good. Later, Rousseau built his political theory around citizen participation in political decision-making (Pateman, 1970). Rousseau’s theory is rooted in a democratic political system that values the economic and financial equality of citizens, their freedom, interdependence, cooperation, and active participation in political decisions. Participative democracy rests upon citizens’ empathy, respect, and tolerance towards each other, their civic commitment, and their willingness to dedicate time and energy for the collective good (Salamon, 2002). However, citizens’ inclination to engage in public good initiatives is influenced by the tools and policies implemented by public actors (Salamon, 2002) and the establishment of cooperative and trust-based relationships.

Place marketing, as a governance process (Eshuis et al., 2014), requires the support and engagement of citizens. In fact, residents are the major stakeholders in place marketing, since they are not only passive beneficiaries of the place, but also co-producers and ambassadors for the place.

Citizens as consumers: According to Kotler et al. (1993), the fundamental objective of place marketing is to effectively cater to the requirements of its residents, who represent a substantial and significant target audience. The endeavors associated with place marketing and place branding possess a dual orientation. On one hand, there is an outward focus aimed at enhancing the competitive standing of the place, with the aim of attracting investments, tourists, or new residents. On the other hand, there is an inward focus directed towards the local population, intending to foster their acceptance of the place’s new developments, cultivate a deep sense of pride and belonging, reinforce their identification with the place, and stimulate novel forms of local mobilization.

As Insch & Florek (2008) point out, a diverse and appropriately skilled population is essential for the sustainability of the place. Cities, by their very nature, depend on their inhabitants for their economic, social, cultural, and environmental dynamism.

It is, therefore, essential to ensure a high level of satisfaction among the local population, as this may influence their decision to stay or to seek other places to live.

Citizens as co-producers: Local communities must be involved in the different stages of the design and implementation of the place marketing and the place branding processes (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, 2008), in collaboration with other stakeholders.

In place branding, the community’s history, heritage, and culture are essential to the development of a place brand (Merrilees et al., 2012).

Citizens as ambassadors of the place: Residents who possess a strong sense of identification with a particular place and find genuine satisfaction in its offerings assume the vital role of becoming the place’s most influential ambassadors. The perspectives and opinions of local individuals carry significant weight for various target audiences due to their perceived authenticity and reliability. These viewpoints are often disseminated through social networks or exchanged through conversations with potential targets, thereby exerting a considerable impact on shaping perceptions and decisions.

Place attachment, developed through various disciplines, is found to be one of the main predictors of citizens’ willingness and motivation to participate in activities that are beneficial to their place.

Through this paper, we aim to explore the importance of citizen participation in place marketing and to examine the relationship between place attachment and citizen participation by drawing a conceptual model that highlights the predictors and consequences of place attachment.

Literature Review

Place marketing and place branding

Strongly developed in the 1970s, with the work of Kotler & Levy (1969), place marketing finds its oldest roots, according to the historian Ward (1998), in the 19th century, when places deployed efforts, mostly through place promotion, to attract tourists and visitors.

Place marketing has evolved significantly through several phases.

Kavaratzis & Ashworth (2008) distinguish between three phases:

- The stage of place promotion (17th century to 1980): This phase is characterized by the intensive use of advertising and other promotional tools to attract new residents and tourists, on the one hand, and by the implementation of subsidies and amenities to attract industries, on the other hand. This phase is also characterized by the improvement of infrastructure through public-private cooperation.

- The stage of planning instrument (1990): This phase is characterized by the development of urban planning and management. Marketing approaches and tools were transposed and applied to the public sector.

- The stage of corporate brand (since 2000): This phase is characterized by the use of corporate brand management in place management.

Along with this evolution, a major lack of conceptual clarity is observed in the literature. The term “place branding” is now commonly used to designate the entire field of place marketing, place branding and brand strategy (Skinner, 2008). This confusion is the result of the emergence of two distinct streams of literature. Some scholars (e.g., Braun, 2008; Kotler et al., 1993) consider the brand as a communicative instrument and a strategic tool of place marketing that aims to trigger positive associations, add meaning or value to places and differentiate the place from other competitors by forging particular emotions and psychological associations with a place (Eshuis et al, 2014). Others (e.g., Hankinson, 2010; Kavaratzis, 2004), on the other hand, consider place branding as a new phenomenon and a separate field of study, resulting from the shift of place promotion and planning towards branding (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, 2008).

Therefore, it’s important to distinguish between the two concepts.

- Place marketing refers to the “coordinated use of marketing tools supported by a shared customer-oriented philosophy, for creating, communicating, delivering and exchanging urban offerings that have value for the city’s customers and the city’s community at large” (Eshuis et al, 2014).

- Place branding refers to “the development of brands for geographical locations, with the aim of triggering positive associations” (Eshuis & Klijn, 2012). It’s, therefore, “an element within place marketing, that involves influencing people’s ideas by forging particular emotional and psychological associations with a place” (Eshuis et al, 2014).

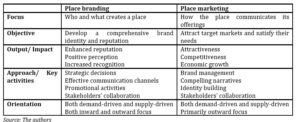

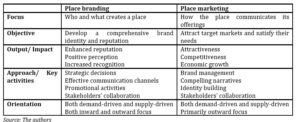

The main differences between the two concepts are summarized (see table 1).

Table 1: Place marketing Vs Place branding

Source: The authors

Stakeholders’ involvement in place marketing

The importance of stakeholders’ engagement in place marketing and place branding has been extensively emphasized in the literature (e.g., Houghton & Stevens, 2010; Kavaratiz, 2012; Hankinson, 2010; Aitken & Compelo, 2011; Braun, 2008; Eshuis et al, 2014; Kavaratzis & Hatch, 2013; Merrilees et al, 2012; Moilanen & Rainisto, 2009; Hanna & Rowley, 2011).

Stakeholder engagement, achieved through a participatory and iterative approach, is crucial for the success of both place marketing and place branding.

Firstly, mobilizing different stakeholders is likely to foster a greater sense of belonging, citizenship, and ownership. This is vital for developing enthusiastic ambassadors and advocates who will promote the place and convey positive messages about it. Additionally, place branding often invites hostility, a sense of threat, and skepticism among many stakeholders (Houghton & Stevens, 2010). However, through participation, place managers can demonstrate the importance and benefits of the branding process.

Stakeholder engagement also serves to deepen and enrich the quality of place marketing strategies, plans, and branding by incorporating new ideas, opinions, and perspectives. In place branding, the interaction of stakeholders can generate new meanings for the brand (Aitken & Compelo, 2011), thereby bringing it closer to the essence of the place (Kavaratzis, 2012). Furthermore, stakeholder engagement creates value by fostering strong relationships through a collaborative approach (Hankinson, 2010).

Citizen participation in place marketing

There is an extensive literature on place-based marketing activities that target external audiences, particularly tourists (e.g., Hankinson, 2004; Hanna & Rowley, 2011). Attention is slowly shifting towards a “dominant service logic” which emphasizes the importance of internal audiences (i.e., residents) who are not only targets of place marketing, but also co-creators and ambassadors of the place.

Citizen participation in urban planning, place marketing and place branding, is the subject of a growing interest in the literature (e.g., Freire, 2009; Garcìa, 2006; Braun et al, 2013).

This interest arises primarily from the transition towards participatory democracy, which emphasized citizen participation in public management and decision-making.

Additionally, the interest is further fueled by the advancements in digital technologies that enable citizens to take an active role in place marketing. With the help of websites, discussion forums, and mobile applications (crowdsourcing), citizens can respond to surveys and consultations, as well as promote their place by sharing content on social networks and building ambassador communities. Moreover, through digital means, citizens can contribute to the assessment of place marketing efforts by writing reviews or submitting suggestions (Hereźniak, 2017).

Furthermore, place marketing constitutes a governance process (Eshuis et al., 2014) and a form of public management that relies on public support for a multitude of social and political motives.

Several researchers have demonstrated the value of citizen participation in place marketing, and more specifically in place branding.

The involvement of citizens in place marketing contributes towards enhancing the place’s internal and external attractiveness and brings forth a range of political, social, and economic stakes.

First of all, citizen participation enables the establishment or re-establishment of trust between elected officials and citizens. Given the growing public distrust towards government entities, structured and efficient citizen participation that ensures equitable representation of diverse social groups plays a vital role in enhancing the legitimacy of decisions, clarifying the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, resolving conflicts and opposition, and constructing the collective interest.

Furthermore, citizen participation allows for a better understanding of residents’ expectations, with the aim of satisfying them.

It also enables the development of a place brand that aligns with the actual values of the place, making it more inclusive, creative, and legitimate.

Such involvement allows for the integration of citizens’ emotions into local governance (Eshuis et al., 2014), thereby improving the quality of the place brand.

Moreover, place brand image and place attachment cannot be established without the engagement of citizens in the values that the brand represents and embodies. According to Houghton & Stevens (2010), place branding initiatives that do not rely on citizen participation are generally doomed to failure.

Furthermore, citizen participation plays a crucial role in analyzing and assessing the place, creating a shared strategy and vision, defining place identity and culture, formulating, and communicating the place offer, and delivering the place experience to different targets.

In place branding, Braun et al (2013) define three different roles of residents:

- Integrated part of a place brand: Residents are regarded as a vital component of the place brand, and they participate in the process of creating and implementing the brand strategy. Residents can help define the brand’s identity and personality, as well as create a consistent experience for visitors and investors.

- Ambassadors for their place brand: Residents can promote their place to family, friends, and colleagues, as well as on social networks and travel blogs. Residents can also participate in local events and activities to build a sense of belonging and pride.

- Citizens: Residents are considered active and engaged citizens who actively participate in place branding. They can work with local authorities to improve the local quality of life, promote sustainable development, and encourage innovation. Residents can also contribute to the creation of local networks and communities to strengthen the social community and encourage social cohesion.

Citizen participation can take different levels and different processes. Several authors have proposed different levels of citizen involvement.

Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of citizen participation highlights eight levels of citizen participation; manipulation, therapy, information, consultation, placation, partnership, delegated power and citizen control. These levels illustrate a progression from limited or superficial citizen involvement to meaningful and substantive participation, with the goal of achieving more democratic and inclusive decision-making processes.

Pretty et al (1995) distinguish between manipulative participation, passive participation (information sharing), participation by consultation, participation for material incentives, functional participation, interactive participation, and self-mobilization.

Place Attachment

For some scholars (e.g., Halpenny, 2006; Brocato, 2007; Ramkissoon et al, 2012), place attachment stems from Bowlby’s (1969) attachment theory, which emphasizes the impact of early relationships on a person’s later social and emotional development.

Other scholars (e.g., Lewicka, 2011) believe that place attachment originates from Fried’s (1963) research on the forced relocation of individuals.

A significant interest in the connections between individuals and places emerged in the 1970s, among humanist geographers and sociologists, under a phenomenological approach.

From the 1980s onwards, environmental psychologists began to examine people-place bonds, drawing on different disciplines to underpin specific concepts in their research.

Other disciplines have also contributed to the enrichment of the theory, such as urban planning, marketing, and tourism.

From this multi-disciplinary perspective, several concepts, definitions, and approaches have emerged around place attachment, creating confusion.

As Williams & Miller (2020) argue, research related to place attachment does not form a single body of literature, but rather, constitute diverse and multidisciplinary studies and investigations, resulting in a variety of perspectives and a lack of consensus.

People-Place bonds

The ties that individuals develop toward places are diverse and range from fairly specific constructs (such as place dependence or place identity) to rather vague concepts (such as rootedness or sense of place).

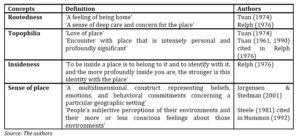

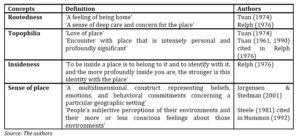

According to Altman & Low (1992), place attachment both encompasses and is encompassed by multiple analogous concepts (see table 2), such as topophilia (Tuan, 1974), place identity (Proshansky et al., 1983), sense of place/rootedness (Chawla, 1992), and community sentiment and identity (Hummon, 1992), to name a few.

Table 2: Definitions of some people-place bonds

Source: The authors

These constructs are defined differently across disciplines, approaches, and authors’ epistemology. Similarly, the relationships between the different concepts are understood differently in the literature. As a result, several concepts are used synonymously leading to a great deal of confusion and a lack of theoretical consistency (Hernández et al., 2014).

Despite their plurality, all these concepts attempt to define some aspect of place attachment (Williams & Miller, 2020).

Definition of place attachment

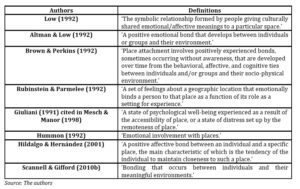

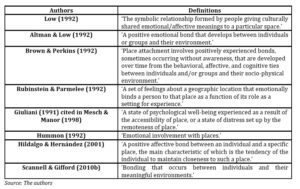

Place attachment has attracted the interest of several scholars (see table 3), belonging to different disciplines.

Some have attempted to identify its processes (e.g., Cross, 2015), others have presented its different types (e.g., Lewicka, 2011), antecedents (Dwyer et al., 2019), implications and consequences (e.g., Sullivan & Young, 2018).

In environmental psychology, place attachment refers to “a positive connection or bond between a person and a particular place” (Williams & Vasque, 2003). It reveals an affective attitude that people have toward the place and is often linked to several analogous concepts.

In sociology, place attachment is an affective bond, studied through the link to the community and to the neighborhood.

Table 3: Definitions of place attachment

Source: The authors

In humanist geography, place attachment is a feeling linked to the meanings that individuals attribute to the territory.

In leisure sciences, place attachment refers to the attachment to natural spaces and is composed of an emotional attachment and a functional attachment.

From a commercial perspective, attachment to the place of consumption is a positive affective link between consumers and the place of consumption (Debenedetti, 2007).

In tourism and marketing, place attachment is an affective link that individuals establish with a specific place and that is characterized by a strong tendency to maintain this relationship (Braun et al., 2013).

Dimensions of place attachment

Scholars have generally conceptualized place attachment as a multidimensional construct.

An initial two-dimensional conceptualization (e.g., Gross & Brown, 2008; Lee et al., 2012; Loureiro, 2014; Williams & Vasque, 2003) emphasizes two dimensions; place identity and place dependence.

Other researchers in different disciplines have added two more dimensions (e.g., Hidalgo & Hernández, 2001; Kyle et al., 2003; Ramkissoon et al., 2013); affective and social attachment.

Additional dimensions have been explored in various research contexts to explore specific issues.

Place Identity

Based on self-theory, Proshansky (1978) was the first to introduce the concept of place identity to emphasize the importance of places in the formation of individual identities.

Proshansky et al. (1983) define place identity as “those dimensions of self that define the individual’s personal identity in relation to the physical environment by means of a complex pattern of conscious and unconscious ideas, feelings, values, goals, preferences, skills, and behavioral tendencies relevant to a specific environment”.

According to self-theories, personal identity is formed as a result of distinguishing oneself from others and identifying oneself through relationships with others (Proshansky et al., 1983).

The development of personal identity “is not limited to making distinctions between oneself and others but extends with no less importance to objects and things, and the very spaces and places in which they are found” (Proshansky et al, 1983).

Proshansky states that place identity is formed through the interaction between the physical environment and the individual personality. He points out that the physical characteristics of a place, such as its shape, size, color, and texture, can influence a person’s feelings and emotions toward that place. Similarly, a person’s habits and behaviors can influence how they perceive and remember a place.

Place Dependence

Derived from the transactional approach, place dependence refers to the functional aspect of place attachment (Brocato, 2007) and assesses the strength of the association between an individual and their place, based on two main factors; the quality of the current place and the relative quality of alternative places (Stokols & Shumaker, 1981).

The quality of the place refers to its capacity to facilitate the achievement of its inhabitants’ goals and to enable them to carry out their preferred activities. The evaluation of the place quality makes it possible to define the degree of satisfaction of its occupants.

The relative quality of alternative places arises from the evaluation of the current place by its occupants in comparison to other potential places where they could carry out their activities.

Affective Attachment

Affective attachment refers to the emotional bond formed with a place, which contributes to the generation of feelings of well-being and security (Nielsen-Pincus, 2010), and consequently increases the level of place satisfaction (De Rojas & Camarero, 2008).

Affective attachment is characterized by intense and positive emotions towards a place, and it evolves and strengthens over time as individuals deepen and diversify their experiences with the place (Relph, 1976).

Social Attachment

Social attachment arises from social interactions in a particular place (Scannell & Gifford, 2010a) and refers to the emotional bonds between individuals in the same place (Raymond et al., 2010).

A place may be valued by an individual because it facilitates interpersonal relationships and promotes group membership.

According to Altman & Low (1992), several interpersonal (between individuals), communal (between individuals and the community), and cultural (between individuals and the culture), relationships occur within places.

Social attachment involves feelings of belongingness to a group and emotional connections based on shared history, values, interests or concerns (Perkins & Long, 2002).

Other dimensions of place attachment

Other dimensions have been developed in different research contexts to explore specific issues.

In the tourism context, Chen et al. (2014) proposed two additional dimensions to interpret tourists’ place attachment based on a short stay:

Place memory: The strength of memories and stories associated with a place.

Place expectation: The extent to which future experiences are perceived as likely to occur in a given place.

Gosling & Williams (2010) consider the dimension of attachment to nature to examine the link between place attachment and pro-environmental behaviors.

In the context of leisure science, Bricker & Kerstetter (2000) add the dimension of lifestyle.

Tumanan & Lansangan (2012) propose four dimensions; a physical dimension, a social dimension, a cultural dimension, and an environmental dimension, to examine place attachment of people who frequent local coffee shops.

Research hypotheses and conceptual model

Antecedents and consequences of place attachment

- Sociodemographic variables and place attachment

Extensive exploration of the literature, spanning various disciplines and contexts, has shed light on the antecedents of place attachment. Among the multitude of factors examined, sociodemographic variables have emerged as significant contributors.

Noteworthy studies by authors such as Scannell & Gifford (2010a), Brown & Perkins (1992), and Bonaiuto et al. (2006), have underscored the importance of length of residence as a predictor of place attachment.

Specifically, Bonaiuto et al. (2006) discovered that individuals residing in small towns, as well as the elderly, tend to exhibit a stronger sense of place attachment.

In a similar vein, Hummon (1992) found that belonging to minority groups can foster a heightened attachment to a place.

Interestingly, Brown & Raymond (2007) found that individuals with higher levels of education often display a weaker place attachment, possibly due to their increased professional mobility. Lalli (1992) also observed that individuals with higher socioeconomic status tend to have a lesser sense of place attachment. Similarly, Bonaiuto et al. (1999) found that the number of persons living together is positively associated with place attachment.

Moreover, Stedman & Ardoin (2013) observed a gender disparity, noting that women generally develop a stronger place attachment compared to men.

Therefore, based on the above discussion, we develop the following hypothesis H1:

H1. Sociodemographic variables have an effect on place attachment.

H1a. Age has a positive effect on place attachment.

H1b. Being a woman has a positive effect on place attachment.

H1c. Length of residence has a positive effect on place attachment.

H1d. Level of education has a negative effect on place attachment.

H1e. Socioeconomic status has a negative effect on place attachment.

H1f. The number of persons living together has a positive effect on place attachment.

- Place satisfaction and place attachment

Place satisfaction has garnered significant attention in the literature, with differing perspectives on its role in relation to place attachment. Some researchers (e.g., Brocato, 2007; Chen & Dwyer 2017, Lee et al., 2012, Xu et al., 2022; Hosany et al., 2017) view place satisfaction as a predictor of place attachment. Conversely, others (e.g., Ramkissoon et al., 2013; Lewicka, 2011, and Yuksel et al., 2010), consider it as a consequence of place attachment.

In the context of residential settings, Hernández et al. (2014) examined rural areas and discovered that individuals with stronger attachments to their place exhibited higher levels of satisfaction. Bonaiuto et al. (1999) explored residential satisfaction by assessing residents’ perception of the quality of their residential environment (PREQ) and found that PREQ served as a predictor of place attachment. Similarly, Devine-Wright & Lyons (1997) and Chen & Dwyer (2017) also investigated the impact of residential satisfaction and determined that it acted as an antecedent to place attachment.

Based on the aforementioned discussion and prior research findings, we propose a bidirectional relationship between place satisfaction and place attachment. Consequently, we put forth the following hypothesis H2:

H2a. Place satisfaction has a positive effect on place attachment.

H2b. Place attachment has a positive effect on place satisfaction.

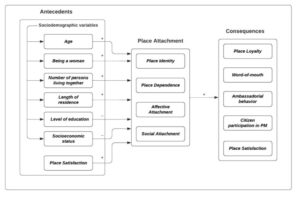

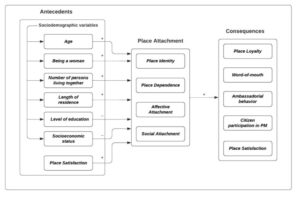

Figure 1: A Conceptual Framework of Place Attachment

Source: The authors

- Consequences of place attachment

Place attachment encompasses a multitude of implications and generates diverse outcomes that have been extensively explored in the literature. Research conducted in residential and tourism contexts consistently highlights the influential role of place attachment in shaping individuals’ intention to revisit a place and their loyalty towards it, as demonstrated in studies by Chen & Dwyer (2017) and Yuksel et al. (2010).

Moreover, place attachment nurtures a profound sense of dedication and willingness among individuals to undertake various beneficial actions aimed at improving the place. Studies by Kyle et al. (2003) underscore the significance of place attachment in fostering commitment and motivation, driving individuals to invest their time and resources for the betterment of the place they are attached to.

At the behavioral level, place attachment exerts a substantial impact on residents, as revealed by Chen & Dwyer (2017). It is intricately linked to ambassadorial behaviors, word-of-mouth promotion, active engagement in activities that contribute to the place’s well-being, and the cultivation of loyalty among individuals.

The observations made by Mohapatra & Mohamed (2013) further emphasize the empowering nature of place attachment, as it motivates residents to actively participate in environmental actions aimed at protecting and preserving their cherished place. This active involvement extends to participating in public meetings, providing valuable suggestions, and contributing to the decision-making process concerning the development of the place.

Furthermore, place attachment assumes a vital role in land restoration and reconstruction efforts (Scannell & Gifford, 2010a). It serves as a driving force behind individuals’ proactive measures in rehabilitating the environment and plays a significant role in fostering pro-environmental behaviors (Halpenny, 2006).

In addition to its influence on individual behaviors and actions, place attachment also establishes a link with citizen participation in place marketing. The sense of ownership and connection that place attachment cultivates motivates residents to actively engage in place marketing initiatives. They willingly contribute feedback, participate in focus groups or surveys, offer ideas for improvement, and collaborate with local authorities or marketing organizations to enhance the image and desirability of the place.

Furthermore, place attachment nurtures social connections and trust among community members, creating a supportive environment that facilitates citizen participation. Residents with strong place attachment feel more comfortable engaging in collective actions, collaborating with others, and actively participating in community-based initiatives.

Moreover, individuals deeply attached to a place possess a heightened understanding of its unique challenges and strengths. This localized knowledge, combined with their emotional connection, enables them to contribute more effectively to problem-solving strategies and initiatives that positively impact their beloved place.

Based on the discussion above, we develop the following hypotheses H3, H4, H5 and H6:

H3. Place attachment has a positive effect on place loyalty.

H4. Place attachment has a positive effect on word-of-mouth.

H5. Place attachment has a positive effect on ambassadorial behaviors.

H6. Place attachment has a positive effect on citizen participation in place marketing.

The conceptual framework (see figure 1) summarizes the research hypotheses.

Discussion

In this model, we put forth six hypotheses that draw from existing literature to examine the intricate relationships between sociodemographic variables, place attachment, place satisfaction, place loyalty, word-of-mouth, ambassadorial behaviors, and citizen participation in place marketing.

To capture the multidimensional nature of place attachment, we represent it as a second-order factor comprising four distinct dimensions: place identity, place dependence, affective attachment, and social attachment. This framework allows for a more nuanced understanding of the various facets that contribute to individuals’ emotional connection to a specific place.

Hypothesis 1 focuses on sociodemographic variables as potential antecedents of place attachment. Specifically, we propose that age, being a woman, length of residence, and the number of persons living together exert a positive influence on place attachment. In contrast, we hypothesize that level of education and socioeconomic status have a negative effect on place attachment, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of education and socioeconomic status may exhibit a weaker attachment to a place.

Moving beyond the individual level, our model considers the role of place satisfaction in shaping the place relationship. We propose that place satisfaction has a positive effect on the overall connection individuals have with a place. However, we also posit a bidirectional relationship between place satisfaction and place attachment, acknowledging that place satisfaction can act as both an antecedent and a consequence of place attachment. This bidirectional relationship underscores the dynamic nature of the interplay between individuals’ satisfaction with a place and their emotional attachment to it.

In the model, we also shed light on place attachment’s important consequences. Consequently, we propose a positive effect between place attachment and various outcomes, including place loyalty, word of mouth, ambassadorial behaviors, and citizen participation in place marketing.

Firstly, we posit that place attachment positively influences place loyalty, indicating that individuals who have a stronger attachment to a place are more likely to demonstrate loyalty towards it. This loyalty can manifest in repeated visits, continued support, and a willingness to defend and promote the place.

Secondly, we propose a positive effect between place attachment and word of mouth. Individuals who feel deeply attached to a place are more inclined to engage in positive word-of-mouth communication, sharing their experiences, and recommending the place to others. Their attachment serves as a motivator for spreading positive information and influencing others’ perceptions of the place.

Thirdly, our model suggests a positive relationship between place attachment and ambassadorial behaviors. Individuals with a strong place attachment are more likely to actively engage in behaviors that contribute to the well-being and improvement of the place. These behaviors may include volunteering, participating in community initiatives, and advocating for the place’s interests.

Lastly, we propose a positive effect between place attachment and citizen participation in place marketing. Place attachment fosters a sense of ownership and connection among individuals, motivating them to actively participate in place marketing efforts. They become valuable contributors by offering feedback, generating ideas, and collaborating with local authorities or marketing organizations to enhance the image and desirability of the place.

By considering these consequences of place attachment, our model provides a holistic and comprehensive understanding of how individuals’ emotional connection to a place influences their behaviors, attitudes, and involvement in shaping and promoting the place’s identity and reputation.

Conclusion, Implications, And Future Research Perspectives

This paper emphasizes the significance of place attachment in fostering citizen participation in place marketing. The involvement of various stakeholders, particularly citizens, is crucial for the success of place marketing and branding initiatives. However, implementing a successful participatory approach requires careful consideration of the tensions and challenges that may arise.

Direct involvement and active participation from citizens can be challenging due to the diversity of individuals with conflicting interests within a place. Additionally, citizens may face constraints such as limited time, skills, or resources, which can hinder their ability to participate effectively. It is essential to recognize and respect the diverse backgrounds and perspectives of citizens, as they contribute to what makes a place unique and desirable.

Place attachment, examined from various dimensions, is conceptualized as a predictor of citizens’ willingness and motivation to participate in place marketing.

The paper proposes a conceptual model that explores the antecedents and consequences of place attachment in the context of citizen participation in place marketing. This conceptual paper provides valuable insights from both theoretical and managerial perspectives. The model extends the conceptual and theoretical understanding of place attachment in a marketing context. However, further empirical research is needed to investigate the link between place attachment and citizen participation in place marketing and branding.

From a managerial standpoint, we believe that the conceptual framework provides valuable insights for practitioners aiming to enhance the attractiveness and competitiveness of their places in today’s rapidly changing environment.

Although the proposed framework offers a holistic perspective, there are both limitations and opportunities for further extension. One important aspect that requires more elaboration is the concept of place satisfaction. In the current model, place satisfaction has been simplified as a unidimensional construct. Therefore, future research should consider incorporating a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of place satisfaction within the model.

Another limitation within this model lies in its exclusive focus on sociodemographic variables as antecedents of place attachment. However, research suggests that other factors like personality traits, psychological characteristics, and mood, also play a significant role in influencing place attachment (Rubinstein & Parmelee, 1992). Hence, the model’s oversight of these important variables restricts its accuracy and comprehensiveness in understanding place attachment.

References

- Aitken R. & Compelo A. (2011). ‘The four Rs of Place Branding’. Journal of Marketing Management 27, 9/10, pp.913–933.

- Altman I. & Low S. M. (1992). Place attachment. New York: Plenum Press

- Arnstein S.R. (1969). ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation’. Journal of American Institute of Planners, 35,4, pp.216-224.

- Bonaiuto M., Aiello A., Perugini M., Bonnes M., and Ercolani A.P. (1999), ‘Multidimensional perception of residential environment quality and neighborhood attachment in the urban environment’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19 pp.331-352.

- Bonaiuto M., Fornara F. & Bonnes M. (2006). ‘Perceived residential environment quality in middle- and low-extension Italian cities’. European Review of Applied Psychology, 56, pp.23–34.

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol. 1. Loss. New York: Basic Books.

- Braun E. (2008). City Marketing: Towards an Integrated Approach. Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM), Rotterdam. ERIM PhD Series in Research and Management, 142.

- Braun E., Kavaratzis M. & Zenker, S. (2013). ‘My city – my brand: The different roles of residents in place branding’. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6,1, pp. 18–28.

- Bricker K. S. & Kerstetter D. L. (2000). ‘Level of specialization and place attachment: An exploratory study of whitewater recreationists’, Leisure Sciences, 22,4, pp. 233-257.

- Brocato D. (2007). Place attachment: An investigation of environments and outcomes in a service context. Phd.

- Brown G. & Raymond C. (2007). ‘The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment’. Applied Geography 27,2, pp.89-111.

- Brown B. B. & Perkins D. D. (1992). Disruptions in place attachment in Altman I. and Low S.M. Place Attachment, New York: Plenum Press.

- Cross J.E. (2015). ‘Processes of Place Attachment: An Interactional Framework’. Symbolic Interaction, 38,4, pp.1-28.

- Chawla L. (1992). Childhood place attachments in Altman I. & Low S.M. (ed) Place Attachment. New York: Plenum Press.

- Chen C.C. & Dwyer L. (2017). ‘Residents’ Place Satisfaction and Place Attachment on Destination Brand-Building Behaviors: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation’. Journal of Travel Research, 57,1, pp.1-16.

- Chen C.C., Dwyer L. & Firth T. (2014). ‘Effect of dimensions of place attachment on residents’ word-of-mouth behavior’. Tourism Geographies, 16,5, pp.826-843.

- De Rojas C. & Camarero C. (2008). ‘Vistors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center’. Toursim Management, 29,3, pp.525-537.

- Debenedetti, A (2007). ‘Une synthèse sur l’attachement au lieu: conceptualisation, exploration et mesure dans le contexte de la consommation’. XXIIIème Congrès International de l’AFM, France.

- Devine-Wright P. & Lyons E. (1997). ‘Remembering Pasts and Representing Places: The Construction of National Identities in Ireland’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 17, pp. 33-45.

- Dwyer L., Chen C.C. & Lee J.J. (2019). ‘The role of place attachment in tourism research’. Journal of Travel and Tourism marketing, 36,5, pp.645-652.

- Eshuis J. & Klijn E.H. (2012). Branding in Governance and Public Management. Routledge, London.

- Eshuis J., Klijn E.H. & Braun E. (2014). ‘Marketing Territorial et Participation Citoyenne: le Branding, un moyen de faire face à la dimension émotionnelle de l’élaboration des politiques ?’. Revue Internationale des Sciences Administratives, 80, 1, pp.153-174.

- Insch A. & Florek M. (2008). ‘A great place to live, work and play: Conceptualizing place satisfaction in the case of a city’s residents’. Proceedings of the Inaugural Conference of the Institute for Place Management. Institute for Place Management. London, England.

- Freire J.R. (2009). ‘‘Local People’ a critical dimension for place brands’. Journal of brand management, 16, pp.420-438

- Fried M. (1963). Grieving for a lost home. In Duhl L.J. (Ed.) The urban condition: People and policy in the Metropolis. New York.

- Garcìa M. (2006). ‘Citizenship Practices and Urban Governance in European Cities’. Urban Studies, 43,4, pp.745–765.

- Gosling E. & Williams K.J. (2010). ‘Connectedness to nature, place attachment and conservation behaviour: Testing connectedness theory among farmers’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30,3, pp.298–304.

- Gross M. J. & Brown G. (2008). ‘An empirical structural model of tourists and places: Progressing involvement and place attachment into tourism.’ Tourism Management, 29,6, pp.1141–1151.

- Halpenny E. A. (2006). Environmental behavior, place attachment and park visitation: A case study of visitors to Point Pelee National Park. Dissertation. Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON.

- Hankinson G. (2004). ‘Relational network brands: Towards a conceptual model of place brands’. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10,2, pp. 109-121.

- Hankinson G. (2010). ‘Place branding research: A cross-disciplinary agenda and the views of practitioners’. Place branding and public diplomacy, 6, pp.300-315.

- Hanna S. & Rowley J. (2011). ‘Towards a Strategic Place brand management-Model’. Journal of marketing management, 27, 5/6, pp.458-476.

- Hereźniak M. (2017). ‘Place Branding and Citizen Involvement: Participatory Approach to Building and Managing City Brands’. International Studies, Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal, 19,1, pp.129-142.

- Hernández B., Hidalgo C. M. & Ruiz C. (2014). ‘Theoretical and methodological aspects of research on place attachment. In Manzo L. & Devine-wright P. (Eds.) Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications, London: Routledge.

- Hidalgo M. C. & Hernández B. (2001). ‘Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21,3, pp.273–281.

- Hosany S., Prayag G., van der veen R., Huang S. & Deesilatham, S. (2017). ‘Mediating effects of place attachment and satisfaction on the relationship between tourists’ emotions and intention to recommend’. Journal of Travel Research, 56,8, pp.1079–1093.

- Houghton J.P. & Stevens A. (2010). City Branding and stakeholder engagement, in Dinnie K. (ed) City branding: Theory and cases. England: Palgrave-McMillan.

- Hummon D. (1992). Community Attachment: Local Sentiment and Sense of Place in Altman I. & Low S.M. Place Attachment, New York: Plenum Press.

- Jorgensen B. S. & Stedman R. C. (2001). ‘Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21,3, pp.233–248.

- Kavaratzis M. & Ashworth G.J. (2008). ‘Place marketing: How did we get here and where are we going?’. Journal of Place Management and Development, 1,2, pp.150-165.

- Kavaratzis M. (2012). ‘From necessary evil to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in Place Branding’. Journal of Place Management and Development, 5,1, pp.7-19.

- Kavaratzis M. & Hatch M.J. (2013). ‘The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory’. Marketing Theory,13,1, pp. 69-86.

- Kavaratzis M. (2004). ‘From City Marketing to City Branding: Towards a Theoretical Framework for Developing City Brands’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 1,1, pp.58-73.

- Kotler P. & Levy S.J. (1969). ‘Broadening the Concept of Marketing’. Journal of Marketing, 33, pp.10-15.

- Kotler P., Haider D. & Rein I. (1993). Marketing Places: Attracting Investment, Industry and Tourism to Cities, States and Nations. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Kyle G., Graefe, A. & Manning R. (2003). ‘Satisfaction derived through leisure involvement and setting attachment’. Leisure/Loisir, 28,3-4, pp.277–305.

- Lalli M. (1992). ‘Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement and empirical findings’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12, pp.285-303.

- Lee J., Kyle G. & Scott D. (2012). ‘The Mediating Effect of place attachment on the relationship between festival satisfaction and loyalty to the festival hosting destination’, Journal of Travel Research, 51,6, pp.754-767.

- Lewicka, M. (2011). ‘Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years?’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31,3, pp.207–230.

- Loureiro S.M.C. (2014). ‘The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions’. International journal of hospitability management, 40, pp.1-9.

- Merrilees B., Miller D & Herington C. (2012). ‘Multiple stakeholders and multiple City brand meanings’. European Journal of Marketing, 46,7/8, pp.1032-1047.

- Mesch G. S. & Manor O. (1998). Social ties, environmental perception, and local attachment. Environment and Behavior, 30, 227-245.

- Mohapatra B. & Mohamed A.R. (2013). ‘Place Attachment and participation in management of neighborhood green space: A place-based community management’. International Journal of sustainable society, 5,3, pp.266-283.

- Moilanen T. & Rainisto S.K. (2009). How to Brand Nations, Cities and Destinations. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Nielsen-Pincus M. (2010). ‘Sociodemographic effects on place bonding’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30,4, pp.443-454.

- Pateman C. (1970). Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Perkins D.D. & Long D.A (2002). ‘Neighborhood sense of community and social capital: A multi-level analysis’. In Fischer A.T., Sonn C.C. & Bishop B.J. (Eds.), Psychological sense of community: Research, applications, and implications. Kluwer Academic/plenum Publishers.

- Pretty J.N., Guijt I.M., Thompson J. & Scoones I. (1995). Trainers’ Guide for participatory learning and action. IIED, London.

- Proshansky H. M. (1978). ‘The city and self-identity’. Environment and Behavior, 10,2, pp.147–169.

- Proshansky H.M., Fabian A.K. & Kaminoff R. (1983). ‘Place Identity: Physical world socialization of the self’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3, pp. 57-83.

- Ramkissoon H., Weiler B. & Smith, L. (2012). ‘Place attachment and pro-environmental behavior in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework’. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20,2, pp.257–276.

- Ramkissoon H., Smith, L. D. G. & Weiler, B. (2013). ‘Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach’. Tourism Management, 36, pp.552–566.

- Raymond C. M., Brown, G. & Weber, D. (2010). ‘The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30,4, pp.422–434.

- Relph E., (1976). Place and placelessness. London, UK: Pion Limited.

- Rubinstein R., Parmelee P. (1992). ‘Attachment to place and the representation of the life course by the elderly’ in Altman I. & Low S.M. Place Attachment, New York: Plenum Press.

- Salamon L.M. (2002). The tools of governance: A guide to the New Governance. Oxford University Press.

- Scannell L. & Gifford, R. (2010a), ‘The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30,3, pp.289–297.

- Scannell L. & Gifford, R. (2010b). ‘Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30,1, pp.1–10.

- Skinner H. (2008). ‘The Emergence and Development of Place Marketing’s confused Identity’. Journal of Marketing Management, 24,5/6 pp.915-28.

- Stedman R.C. & Ardoin N. (2013). ‘Mobility, power, and scale in place-based environmental education’. in Krasny M.E & Dillon J. (Eds.) Trading Zones in Environmental Education. New York: Peter Lang.

- Stokols D. & Shumaker S. A. (1981). ‘People in places: A transactional view of settings’ In Harvey J.H. (Ed.) Cognition, social behavior, and the environment, pp. 441–488, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

- Sullivan D. & Young I.F. (2018). ‘Place Attachment Style as a Predictor of Responses to the Environmental Threat of Water Contamination’. Environment and behavior, 52,1, pp.1-30.

- Tuan Y.F. (1974). Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes, and values. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Tumanan M.A.R & Lansangan J.R. (2012). ‘More than just a cuppa coffee: a multi-dimensional approach towards analyzing the factors that define place attachment’. International journal of hospitability management, 31,2, pp.529-534.

- Ward S.V. (1998). Selling Places: The Marketing and Promotion of Towns and Cities, E &F.N. London.

- Williams D. R. & Vaske J. J. (2003). ‘The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach’. Forest Science, 49,6, pp.830-840.

- Williams D.R., Miller B.A. (2020). ‘Metatheoretical moments in Place attachment research: Seeking Clarity in Diversity’ in Manzo L.C & Devine-Wright P. Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications. Routledge.

- Xu Y., Wu D. & Chen N.C. (2022). ‘Here I belong!: Understanding immigrant descendants’ place attachment and its impact on their community citizenship behaviors in China’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 79, pp. 1-11.

- Yuksel A., Yuksel, F. & Bilim, Y. (2010). ‘Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty’. Tourism Management, 31,2, pp.274–284.