Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a particular disciplinary field (Mr BOUSETTA, 2011), in the sense that it has recently undergone a great and obvious development and an important scientific interest. Indeed, the creation of companies has proved to be a real factor of economic growth, that’s why the study of this field has become the center of the analyses and the theoretical debates.

The female company is part of this development engine and the question of women entrepreneurs cannot be neglected when we talk about this rise in the field of entrepreneurship and about the role of micro and small and medium-sized female Moroccan companies. Those are seen as a means of providing employment opportunities, wealth creation, income distribution and poverty reduction.

A significant number of these women use entrepreneurship as a dilemma for the wage and the diploma crisis, which is why a large number of women are operating in the informal sector just to fill their financial needs. Nevertheless, there are other women fighters who prefer to start their own business and be their “own boss” instead of being employed in the public or private sector to achieve a specific objective or goal.

If entrepreneurship is analyzed as a process, then every effort should be made to ensure that this process does not end and stop after a few months or years. The existing company must remain entrepreneurial to increase its chances of survival (E.M. HERNANDEZ, 2006). These women’s enterprises there are condemned to disappear due to many difficulties and failures that do not concern only the financial field as it is known, and do not affect only small and medium-sized enterprises. It can concern all areas of the company, regardless of its size, even those quoted on the stock market.

The analysis of the concept of the distress of a company has always been the essential element of investigation of researchers and people concerned in the field. These situations of failure influence and impact the continuity of the business activity, or even its existence. Nevertheless, few studies have been conducted on the concept of failures from Moroccan women’s enterprises and their recovery. Hence the purpose of this paper which aims to fill this theoretical vacuum and provide researchers with enough data on this aspect of the female entrepreneurship.

The main purpose of this research is to conduct an exploratory study to present the situation of female Moroccan companies. The results of this survey will allow us to identify the type of failures that women entrepreneurs face, the period of these crises and how they solve their problems.

Theoretical Frame

Female Entrepreneurship in Morocco: A Continuous Evolution

Contrary to what can be seen in several countries of sub-Saharan Africa, women entrepreneurs are not numerous in Morocco. According to AFEM[i], the percentage of women entrepreneurs is only 11%, except that this proportion disguises the reality of female entrepreneurial dynamism, caused mainly by the weight of the informal sector.

The economic evolution of the country has pushed and encouraged the Moroccan woman to go beyond this spectator’s cape and become an active and not passive player in society, and since the number of women’s businesses (created and managed by women) continues to increase , slowly but surely.

Since the arrival of King Mohammed VI to the throne, the status of women in the kingdom has been marked by notable improvements. Women’s entrepreneurship has become a vital engine for the dynamism of Morocco’s economy. In fact, the international studies of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) have shown the strong correlation between the female entrepreneurial activity rate and economic growth. Also, the public authorities of many countries now include women’s entrepreneurship in their economic policy planning. A claim that argues the development of this field was neglected before and seen as a completely wasteland.

Today, the encouragement of the entrepreneur woman and her company in Morocco is part of an approach to promote and develop the current situation of women in different sectors and fields. Tangible results started to be produced/show, since there is a noticeable growth in women’s entrepreneurship that shows up in their participation in economic development.

The essential triggering factor for this change in the state of mind is the appearance of the new family code, the Moudawana, which has contributed to the spread of this new culture based on the principles of concrete equality between women and men.

- The profile of Moroccan women’s enterprises

The companies which are created and managed by women are generally small of size considering their manpower and their sales turnover. They are located and operated in the most traditional sectors of activity, namely services, textiles, trade, catering, hotels and others.

The authors unanimously agreed on the concept of the youth of enterprises created and run by women, as they are generally more recent than those created and managed by men.

The women-run business survey showed that most women’s businesses are micro-enterprises and micro-enterprises as most of their managers either work alone or employ no more than 10 employees.

The specialized center for research on SMEs (LAMBRECHT and PIRNAY, 2003) attaches and attributes the size characteristic to the sector of work as well as to the level of education of the entrepreneur and not to the fact that it is led by a woman. Moreover, a company in the industrial sector employs more people than a company in the services sector.

About two-thirds of women’s businesses, created and run by women, employ fewer than twenty Moroccan workers, half of whom are women. So we face the case of the TPE and SME, which is consistent with the economic reality of Morocco in more than 90% of SMEs.

The ABC (Agency for Business Creation) carried out a study which showed that women’s start-ups are small and less durable than those launched by their male counterparts. 79% of companies created and run by women did not employ employees full-time at the launch of the activity, compared with 76% of companies created and managed by men.

After 3.5 years of creation, the situation has changed for companies concerning the employability of employees; 71% of women entrepreneurs still have no staff, while men are only 59%.

Regarding the sustainability rate and continuity on a five-year scale, it was 45.4% for companies created by men and 41% for companies created by women. Thus, in the case of one in three businesses managed by a woman is 5 years old, and a company in two under 10 years.

In the case of Moroccan women’s businesses, more than 60% of these women are under 10 years of age and about 40% are under 5 years old.

In Morocco, the companies created and managed by women are in most cases SARLs or individual companies with a rate of 57% and 20% respectively. They are also, but rarely, limited companies with 16%. Women entrepreneurs opted for the legal firm LLB (Limited Liability Company) because of its simplicity in question creation certainly, but also given that its start-up capital is not too high.

According to the 1998 ABC (Agency for Business Creation) investigation, women’s enterprises (managed or created by women) are in most cases in the personal services sector. The analysis of the six activities accompanying start-ups by women entrepreneurs noted a remarkable dominance of activities related to the service sector. We find:

- 3% in the personal service

- 60% in the health service and social action

- 7% in the retail trade

- 7% in the clothing industry

- 7% in the hotel and restaurant service

- 6% in the education department.

We therefore note the dominant presence of the tertiary sector in the launch of women’s companies, a thing which impacts the sustainability rate of their companies.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to indicate that recently, women having a diploma of a BAC+3 or more, decide to invest in the tertiary sector of companies. There is a rate of 75% of women with this degree in the service sector, including 51% in the business services sector.

Moroccan women entrepreneurs carry out their work in the agricultural, artisanal and commercial sector in traditionally female areas and cultures.

Women’s percentage who exercise the activity at home is of: 33,1 % in urban zones and 63,8 % in rural areas.

Enterprises created and run by women are present in all sectors of activity; they are mainly and more strongly shown in the services sector with a percentage of 37% and that of commerce and distribution with a percentage of 31%.

However, we note that women who start and run their companies and who have an industrial activity have a particular presence in the textile sector.

The question is, are women entrepreneurs able to sustain and ensure the continuity of their companies? And once problems have occurred, do they arrive to manage them? This is what we will see in this next point.

The Recovery of the Feminine Companies in Failure

The concept of failure

[i] Association of Women Entrepreneurs of Morocco

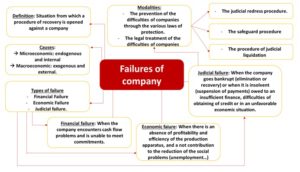

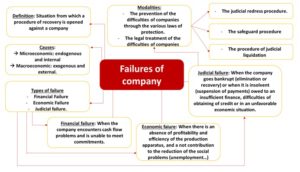

Figure 1: the concept of failure

Source: authors

- Recovery Of Companies In Difficulty

After diagnosing the company when the failure and its type are detected, it will establish objectives, determine phases, and maintain technical orientations. These instructions allow the development of a redress plan.

The recovery of a failing firm, according to D. Schendel, GR Patton and J. Riggs (1976)[i], is defined as “a sequence of a declining period of at least four years, followed by a period of recovery of results of similar duration “[ii].

The assembly of these two periods can give rise to two years of reluctance during which, and after having achieved a first growth, the results re-offend.

Inappropriately, this relapse of the results leaves place for corrective operations only after a very long period; “When the magnitude of the decline no longer allows one to ignore it”[iii].

It is noted that the recovery process then retains a staggering characteristics to a rapid improvement. It is a program that must then show itself as a reasonable sequence of actions that leads to its outcome.

Despite this, the mutations made cannot be limited to minor adaptations. They concern the entire firm to recover and are more of the activity of leaders than a favorable evolution of the environment[iv].

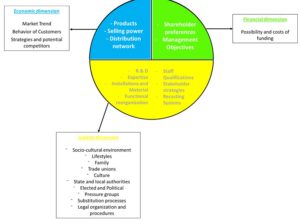

Figure 2: les étapes du processus de redressement

Source : modèle de Scendel, Patton et Riggs adapté

[i] From a population of 1800 firms analyzed over the period 1952-1971, the authors selected 54 industrial enterprises whose results were available and met their definition of recovery.

[ii] G. Koenig, op-cite, p. 89.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Schendel, Patton and Riggs emphasize the contrast with the phases of decline dominated by the inaction of managers who are confronted with deteriorating business conditions.

The recovery plan is defined as “a coherent and dynamic set of actions and measures intended to remove the business from economic difficulties that are likely to jeopardize its entire existence”[i].

The recovery plan is not made randomly; it is prepared in advance and requires a good construction period. First of all, we need to have a very clear and objective vision of the firm wishing to straighten out, with the help of a welded group, and then put it in place with positive energy and a remarkable dynamism thanks to the application of a new management method and the integration of all the dimensions of the company while taking into consideration its internal and external environment in order to succeed in its installation.

[i] N. Guedjali, “Social Aspects of Business Recovery Plans, Positive and Practical Study”, Algerian Journal of Labor, No. 23/98, p. 79.

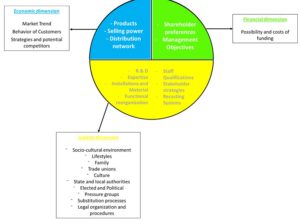

Figure 3 : les dimensions d’un plan de redressement

Source: J.P. Thibaut adapté

The economic action plan is generally based on a few measures developed to attract customers back to the firm and to change the market shares it would have lost and already lost during the crisis period.

It makes it possible to evaluate the production capacity of the firm, as well as the quality of its production mechanism without forgetting the sales force and the manufacturing and distribution processes.

For the financial action plan, it is based on the financial failures that generally arise from an imbalance caused by a mismatch between the financial management of the firm in question and its level of activity.

The legal action plan is put in place when the firm in difficulty goes bankrupt (elimination or recovery) or when it is insolvent (cessation of payment) caused by the appearance of a faulty and insufficient cash which does not support the expenses of the insufficient company, also by the presentation of several obstacles in question of obtaining credit or by an unfavorable economic situation.

- According to BAKIOUI D. and FERHANE D. (2017)[i], here is a schematization of the three different forms of recovery.

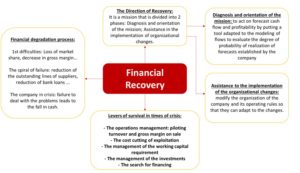

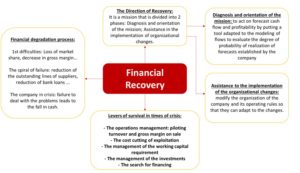

- Recovery of the company in financial distress

[i] AJAJ BAKIOUI Dounia & FERHANE Driss (2017), “The recovery approaches and processes of companies in Difficulties: the case of Moroccan women’s companies”, conference under the theme “Entrepreneurship Research: Past, present & future”. Paris, France.

Figure 4: Financial recovery

Source: Authors

Recovery of the company in crisis of legal type

Figure 5: Legal Recovery

Source: Authors

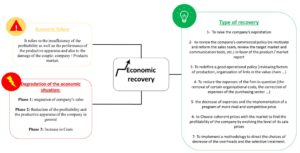

Recovery Of A Company In Economic Difficulty

Figure 6: Economic Recovery

Source: Author

Empirical Frame

The Recovery of Women’s Enterprises in Morocco: A Survey of the Field

Methodology

As part of our study, we have adopted a quantitative approach and we have focused on all private Moroccan women’s enterprises operating in different sectors including: services, trade, industry and others if possible, and in all regions of Morocco, favoring only large cities in each region: Tangier, Rabat, Casablanca, Marrakech, Agadir.

Data collection was performed using a questionnaire that conformed to the selected analysis model. Our model is based on 5 sections with a total of 44 questions:

– The entrepreneur woman: 8 questions

– The women’s company: 12 questions

– Managerial practices: 10 questions

– The environment: 5 questions

– The difficulties and recovery of the company: 9 questions

An explanatory text contains the objectives of the research is sent with the questionnaire that was available on the web from Google Forms under the link: https://goo.gl/forms/xtPgWso68tTxf6yD2

A pre-test of the questionnaire was conducted with 3 respondents who validated the wording of the questions and the choice of answers and estimated the time required to answer the questionnaire.

After three months of investigation from November 2017 to January 2018, we obtained 42 questionnaires, 2 of them are non-exploitable.

It should be noted that data collection is still ongoing. We stopped this study at the level of available answers and chose to analyze just the last part of the questionnaire that meets our objective.

Results

The following section presents information on the vision of women entrepreneurs surveyed on business failures and turnarounds.

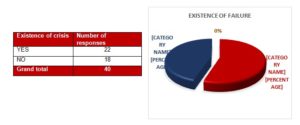

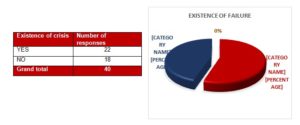

Figure 7: Existence of failure

Of the 40 responses analyzed, more than half of the companies or 55% confirm having gone through a period of crisis, 45% remain unconfirmed of their passage through this period

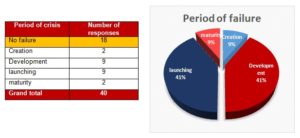

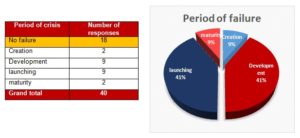

Figure 8: Period of crisis

41% of companies have gone through difficulties during the period of lunching or of development. Only 9% during the creation and the period of the maturity, these two categories remain the least risky and difficult. The alarming periods according to this investigation are the lunching and development of the structure that require additional attention.

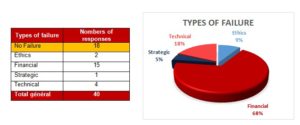

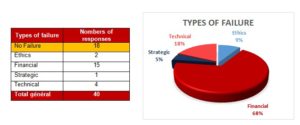

Figure 9: The types of difficulties

According to the respondents, almost 2/3 (68%) of the difficulties encountered are of a financial nature; secondly, there are the technical difficulties which only represent 18% of the cases. The remaining 14% is divided between ethical and strategic difficulties, (9.1% and 4.5% respectively). On the other hand, we note a complete absence of organizational, legal and administrative failures and those relating to market shares.

Figure 10: Causes of failures

59% confirm that the difficulties encountered are attributed to the market, 23% are caused by the difficult economic situation and only 4% of the difficulties are due to the internal problems of the company, same thing for the low working capital or weak FR, the Ethics and the tightening of bank credit policies.

Two main causes are apparent from these graphs (market and economic conditions that account for more than 82% of the reasons for difficulties, other causes include, “the tightening of bank credit policies, the mentality of people, the market and the “Ethics; the organization of the Moroccan administration and low working capital” are insignificant and represent only 17% of cases.

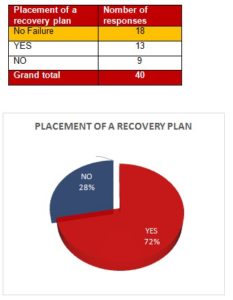

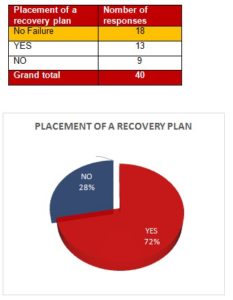

- Placement of a Recovery Plan

Figure 11: Willingness to recover

72% of the respondents showed their interest in establishing a recovery plan to save and improve the situation of their companies, whether at the start-up, at the beginning or during the activity, against 28% who are disinterested.

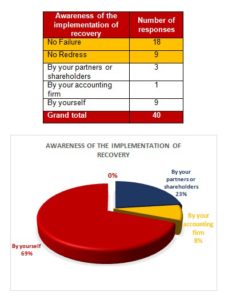

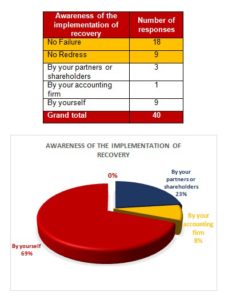

- Awareness of the implementation of recovery.

Figure 12: Awareness of the placement of the recovery plan

The majority of respondents; 69% confirm that the information for a recovery plan was provided by themselves, the use of partners or shareholders represent a small percentage not exceeding 23%. The information provided by a chartered accountant is insignificant (8%). The intervention of the banker and the controller of the firm are totally absent

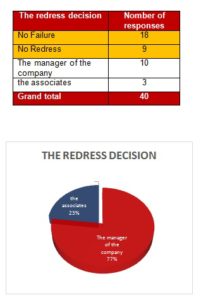

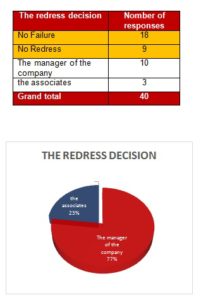

- The person responsible for the decision of the recovery

Figure 13: The decision of the recovery

The recovery plan is developed to 77% of the cases surveyed by the management team, the use of an external team was observed for only 23% of cases

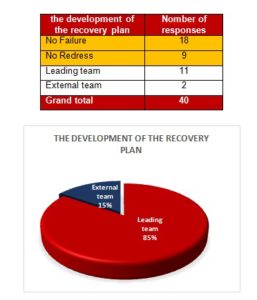

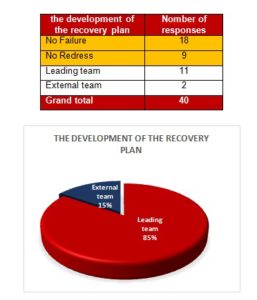

Figure 14: The Person Responsible for Developing the Recovery Plan

The recovery plan is developed in the majority of cases (85% of cases) by the management team of the company against just 15% of contractors who use an external team.

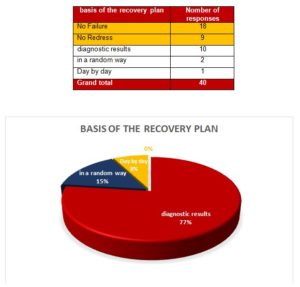

- Design of the recovery plan

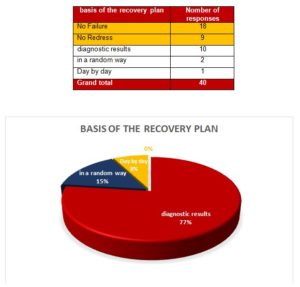

Figure 15: Basis of design of the recovery plan.

The recovery plan is developed in the majority of cases (77% of cases) based on the results of the established diagnosis, 15% of the plans only were developed in a random way, the remaining 8% are developed from day by day . No recovery plan was developed based on the old recovery plans.

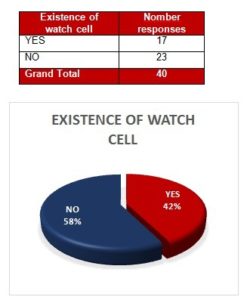

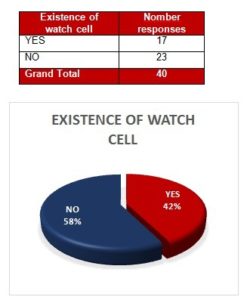

Figure 16: Existence of watch cell

Only 42% of respondents confirm that they have business intelligence cell, 58% or more than half do not have these very important cells for business intelligence.

Figure 17: Type of watch cell

Among the 42% who have a business intelligence cell, 53% have a cell for competition against 47% with cell for strategy.

Conclusion

The purpose of the investigation is to clarify and study the idea of recovery in the Moroccan entrepreneur.

According to our results, at different levels, the majority of women entrepreneurs in our sample face different types of problems as shown in our graphs.

The results of the causes of these problems were not surprising for us; a large rate was awarded to the funding: an expected result. On the other hand, these preliminary results show that Moroccan women entrepreneurs face other problems little known in the literature and that we believe they no longer exist; as market-related difficulties.

To our surprise, recovery is not expected or used by many women entrepreneurs facing failures as noted above.

It should also be noted that this research has faced – and still faces, since the questionnaire is still being distributed – several limitations, including a very harsh one, including the reluctance of a large number of women contractors to answer our questionnaire.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Bibliography

- Afem, (2005), « Etude sur l’entrepreneuriat féminin au Maroc »

- Alesina A.F., Lotti F. et Mistrulli P.E. (2008), “Do women pay more for credit? Evidence from Italy”, NBER Working Papers 14202, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- ATIYA A. F. (2001), Bankruptcy Prediction for Credit Risk Using Neural Networks: A Survey and New Results, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 12, 4,929-935

- Bel G. (2009), « L’entrepreneuriat au féminin », Avis et rapport du Conseil économique, social et environnemental.

- Benabdenbi Djerrari. F. « Marocaines et Entreprises », édition Le Fennec, 1995

- BLAZY R., COMBIER J. (1998), La défaillance d’entreprise : Causes économiques, traitement judiciaire et impact financier, Economica/ INSEE Méthodes n° 72-73, Paris.

- Bosma N., Coduras A., Litovsky Y. et Seaman J. (2012), “GEM manual: A report on the design, data and quality control of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor”, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor project, mai.

- BOUSETTA, M. (2011), « Entrepreneuriat Féminin au Maroc : Environnement et Contribution au Développement Economique et Social » ICBE-RF Research Report No. 10/11

- Boz A., Ergeneli A. (2014). Women entrepreneurs “personality characteristics and parents” parenting style profile in Turkey. Social and Behavorial Science,109, 92-97.

- BRUSH, C. G. & Hisrich, R. D. (1988), « Women entrepreneurs: strategic origins impact on growth », Frontiers in entrepreneurship research, Babson College, p.612- 625.

- Burke, J., Belcourt, M. L., & Lee-Gosselin, H. (1989). Work And Family In The Lives Of Female Entrepreneurs : Having It All? : Centre National de recherche et développement en administration.

- CARRIER C., JULIEN P. A., MENVIELLE W. (2006), « Un regard critique sur l’entrepreneuriat féminin : une synthèse des études des 25 dernières années », Revue Internationale de Gestion, vol. 31, n° 2, pp. 36-50.

- M. HERNANDEZ, (2006), « Extension du domaine de l’entrepreneur… et limites », La Revue des Sciences de Gestion 2006/3 (n°219), p. 17-26. DOI 10.3917/rsg.219.0017

- FERHANE DRISS & AJAJ BAKIOUI DOUNIA (2017), “The recovery approaches and processes of companies in Difficulties: the case of Moroccan women’s companies”, conference sous le theme “Entrepreneurship Research: Past, present & future”. Paris, France.

- HOL S, WESTGAARDS ETWIJST V.N. (2002), Capital structure and the prediction of bankruptcy, EWGFM Conference, Capital Markets Research (Bankruptcy Prediction).

- LIANG L ET WU D. (2003), An application of pattern recognition on scoring Chinese corporations financial conditions based on back propagation neural network, Computers et Operations Research, 32, 1115-112

- PINDADO J., RODRIGUES L.F. (2001), Parsimonious models of financial insolvency in small companies, Working Paper, SSRN Working Paper Series.

- POMPE P.M ETBILDERBEEK J. (2005), The prediction of bankruptcy of small and medium sized industrial firms, Journal of Business Venturing, 20,847-868.

- SHARABANY R (2004), Business failures and macroeconomic risk factors, Discussion paper 06, Bank of Israel, Research Department

- VARETTO F. (1998), Genetic Algorithms Applications in the Analysis of Insolvency Risk, Journal of Banking and Finance, 22, 10-11, 1421-1439.