Introduction

The more time people spent unemployed, the harder it is for them to find employment. We also observe that there are more women than men unemployed in all durations of unemployment in all three territories, but we don’t know if this ratio changes with time or remain steady. We also tend to find how unemployment gender inequality rates by distinct durations in unemployment and territories are affected by economic disturbances that occur. A connection in the structure of the unemployed by distinct time spent in unemployment could also exist. This structure could also be affected by economic disturbances and consequently it could be permanently changed. To find how unemployment gender inequality depends on the duration of unemployment, we compare Spain, Switzerland and the European Union. We chose Spain as a country that had high and turbulent unemployment rates during the observed period, and Switzerland as a country with the lowest and steady unemployment rates during the observed period. The European Union was chosen to represent countries with average unemployment rates. When we compare these three territories, we can find if the structure of durations in unemployment depends on territory chosen or there is some common behaviour that was valid for all of them.

This paper was structured as follows. We start with literature review, where we list results from previous studies of unemployment and gender inequality researching. Afterwards, we describe the methods that were used in this paper for data analysis. Subsequently, we introduce the results from both univariate and panel data unit root tests and results from the dependency of unemployment gender inequality on the duration of unemployment. Finally, we discuss the results and give our conclusions.

Literature Review

The analysis of the gender inequality in unemployment started only in the last twenty years. Even when the analysis of the gender inequality on the labour market started in 1970s, gender inequality in unemployment didn’t receive deserved attention (Spielmann, 2006). Ones of the first that researched gender inequality in unemployment and proposed how it should be analysed, were Azmat, Gűell and Manning (2004) and Queneau and Sen (2007). They analysed unemployment gender inequality by calculating gender gap as a difference between the unemployment rate of women and unemployment rate of men, and as a ratio of unemployment rate of women to the unemployment rate of men. Koutentakis (2015) proposed calculation of the gender gap from the job finding rates and job separating rates, by the construction of the steady state of the gender gap from them. Unemployment gender inequality was also researched using probability analysis on outflows and inflows to unemployment. Ollikainen (2006) claim that, unemployment gender inequality decreases with higher educational attainment. Theodossiou and Zangelidis (2009) discovered that men switch from job to job more easily than women, who instead of switching to another job, switch to unemployment. But they also discovered that with higher educational attainment, these differences were diminishing. Gokulsing and Tandrayen-Ragoobur (2014) discovered that even when women have higher education, men with lower education and performance are preferred by employers. They explain this discrepancy with the wrong choice of vocational attainment of women, who usually studied professions of which labour market was already saturated. Peiro, Belaire-Franch and Gonzalo (2012) claimed that unemployment depends on the business cycle and that economic disturbances affected more men than women, but consequences from it disappeared quickly after the crisis.

Baussola, Mussida, Jenkins and Penfold (2015) discovered that the more time people spent unemployed, more difficult it is for them to find a job, and it is even more difficult for women to enter the labour market. This was also proven by Pašic, Kavkler and Boršič (2011), who discovered that women were unemployed longer than men. Bachmann and Sinning (2016) found that the duration in unemployment was negatively affected by the economic crisis which prolonged it. Flek, Hála and Mysíková (2015) claim that people who were unemployed for more than a year, had lower chances to find a job. They also found that, young people are unemployed longer than others. Böheim, Horvath and Winter-Ebmer (2011) found that the reason why people who were long term unemployed couldn’t find a job was their misleading perception of the wages and the labour market. Arellano (2010) found that the duration of unemployment could be decreased with the implementation of the trainings which could help unemployed to find employment sooner. He also found that women who participated in this type of trainings found jobs faster than men.

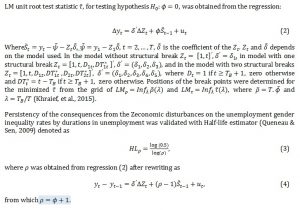

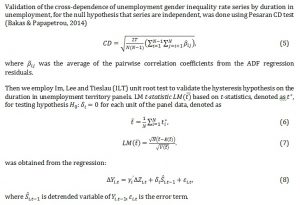

Unemployment hysteresis was analysed by many authors. Ayala, Cunado and Gil-Alana used Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) test and Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test and found a proof that supports hysteresis hypothesis. Camarero, Carrion-i-Silvestre and Tamarit (2008) used Im, Pesaran, Shin (IPS) unit root test, Maddala and Wu’s (MW) unit root test and Hadri unit root test to validate hysteresis hypothesis without including the structural break and Carrion-i-Silvestre, Barrio and López unit root test that allows the inclusion of structural breaks. They found that the rejection of the hysteresis hypothesis depends on the allowance of structural breaks. In tests without structural breaks included, hysteresis hypothesis couldn’t be rejected, but when structural breaks included, the results changed, and the hysteresis hypothesis was rejected. Garcia-Cintado, Romero-Avila and Usabiaga (2015) claimed that hysteresis hypothesis couldn’t be rejected in regions of Spain even when two or more structural breaks were included. The unit root test that was used to validate hysteresis hypothesis were used in the unemployment gender gap analysis as well. Queneau and Sen rejected hysteresis hypothesis using Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) unit root test (2007) and Phillips Perron (PP) unit root test (2009), and found that even unemployment gender inequality is persistent, and is disappearing. Bakas and Papapetrou (2014) confirmed persistency of the unemployment gender inequality using Im, Lee and Tieslau (ILT) unit root test.

We follow Bakas and Papapetrou (2014) and Azmat, Gűell and Manning (2004) methods for hysteresis hypothesis analysis and contribute to the literature by proposing a method of unemployment gender inequality calculation. This method was calculated from quantitative data on the duration of unemployment, and combines Queneau and Sen (2007) method of gender inequality calculation that includes ratios of one to another gender unemployment rate, with levels of the unemployment rates, to avoid high gender inequality in a series of low unemployment rates. We also provide an insight how unemployment gender inequality depends on the duration of unemployment and how economic disturbances influence it.

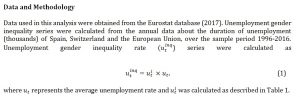

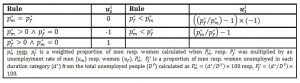

Table 1: Gender inequality calculation rules

Source: Own calculation

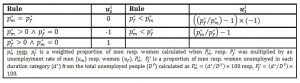

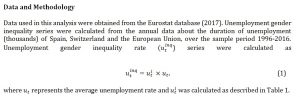

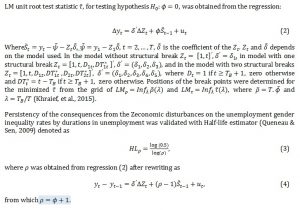

We employ univariate Lagrange Multiplier (LM) unit root test to validate the hysteresis hypothesis in the computed univariate unemployment gender inequality rate series by distinct durations of unemployment for Spain, Switzerland and the European Union. In case that hysteresis hypothesis is rejected, we would prove that unemployment gender inequality rate series doesn’t follow random walk and that means, variance and autocorrelations of the series are constant (Lyócsa, et al., 2011).

Results

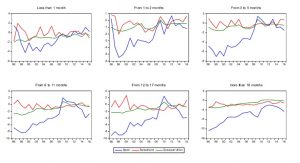

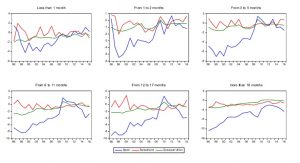

We witness high unemployment gender inequality in Spain, in the beginning of the observed period. Slightly lower, but still the highest unemployment gender inequality for the observed period, was also noticed in the European Union. In all three territories, the unemployment rate of women was, in most of the cases, higher than the unemployment rate of men. Even the unemployment gender inequality was decreasing during the observed period in Spain and the European Union, as for Switzerland, it remained low and steady and oscillated around equality. Economic crisis in 2008 had the highest influence on the Spain and the European Union, where it caused a switch from the unemployment gender inequality to equality in all of the durations in unemployment categories. When we look at the gender

inequality by distinct durations of unemployment and compare them between territories, we observe that the unemployment gender inequality was increasing with more time spent in unemployment, in Spain and the European Union, while remained almost unchanged in Switzerland. We also observe that the unemployment gender inequality of Switzerland in all durations of the unemployment was fluctuating in an interval from -2 to 2, meaning that gender inequality didn’t exist in this country; which also suggests that the unemployment gender inequality in Switzerland didn’t depend on duration in unemployment. There are some similarities in the levels of gender inequality of Switzerland and the European Union, while the unemployment gender inequality of Spain was significantly higher in all durations of unemployment (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: Unemployment gender inequality by distinct durations in unemployment of Spain, Switzerland and the European Union, over the period 1996-2016

Source: Own calculations

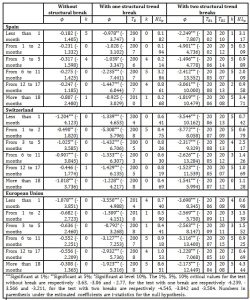

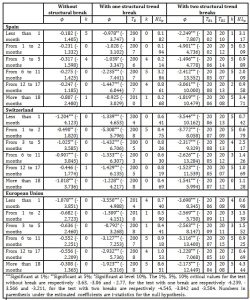

Three models were taken into consideration when validating the hysteresis hypothesis. When validated for model without structural breaks, the hysteresis hypothesis of the unemployment gender inequality couldn’t be rejected for Spain and the European, while in most of the series of the Switzerland was rejected (Table 2). Neglecting structural breaks could lead to false non-stationarity conclusion. This would mean that we considered ideal economic background which behaves smoothly rejecting any occurrence of the economic disturbances that impact it. When economic disturbances are not included in the model and they occur in the economy, it appears that the behaviour of the unemployment gender inequality rate series depends only on its previous values and that policy toward gender inequality are irrelevant. When validated for the model that includes one structural break, hysteresis hypothesis was rejected for all duration series of the European Union and the Switzerland, while still couldn’t be rejected for some duration series of Spain. When looking at the duration series of the European Union, we could observe that structural break occurred around the crisis in 2008 and impacted gender inequality among those who were unemployed for more than three months and consequently gender inequality decreased. Only when validating the model with two structural breaks, hysteresis hypothesis was rejected in all unemployment gender inequality rate series of all three territories (Table 2). We observe that the economic crisis in 2008 impacted all unemployment gender inequality rates series in all three territories and caused diminishing of the gender inequality, but its effect was only temporary and disappeared quickly after the crisis. Even when gender inequality is decreasing, it remains persistent.

Table 2: Results from LM unit root tests

Source: Own calculation

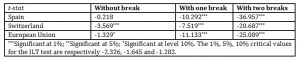

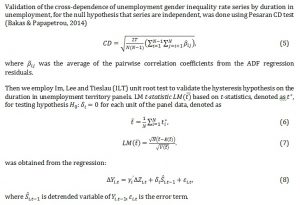

The dependence of the gender inequality on the durations in unemployment was proven with Pesaran CD test (5) for Spain (t-stat 4.113, p-value 0.000) and the European Union (t-stat 5.087, p-value 0.000), while gender inequality of Switzerland didn’t depend on durations in unemployment (t-stat 1.004, p-value 0.315).

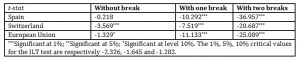

Hysteresis hypothesis was also rejected when validated on duration series panel by Spain, Switzerland and the European Union, with one or two breaks included as well as it was the case with the univariate series. Without break included, only the panel of duration series in Spain exhibited hysteresis behaviour. While in the univariate gender inequality series by duration of unemployment to obtain stationary behaviour in all three territories, two structural breaks had to be included, in panel data with one structural break included, stationary process behaviour was obtained in all three territory duration panels, without necessity to include the second structural break (Table 3).

Table 3: Results from ILT unit root tests

Source: Own calculation

Conclusion

Unemployment gender inequality increased with time spent unemployed in Spain and the European Union, which coincides with the results of Pašic, Kavkler and Boršič (2011), while gender inequality was almost unchanged trough different durations of unemployment in Switzerland. Since the results are different for Switzerland, we had to reject that the common pattern exists between durations in unemployment and the unemployment gender inequality. Even though the unemployment gender inequality is still persistent, and women are those who are in disadvantage, it was decreasing with time. Hysteresis hypothesis was also rejected with breaks included both on univariate and panel data gender inequality series of durations in unemployment in all three territories. Results are consistent with the results of Queneau and Sen (2009) and Bakas and Papapetrou (2014) results of hysteresis hypothesis rejection and persistence of the gender inequality in the unemployment. Economic disturbances had only a temporary effect on the unemployment gender inequality in all durations of unemployment, and affected mostly unemployment of men, which caused the decrease to gender equality, also proven by Peiro, Belaire-Franch and Gonzalo (2012). Even though unemployment gender policies are strong and lead to gender equality, they are still needed, especially in Spain and the European Union where gender inequality increases with time spent in unemployment.

Acknowledgment

This paper was produced as a part of the SYLLF research abroad program, financed by the Nippon foundation, which the first author gratefully acknowledges. First author also acknowledges prof. Cecilio Tamarit for professional guidance and the University Valencia, for providing the access to the University resources and facilities. The second author acknowledges the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-16-0091.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Arellano, F. A. (2010), “Do training programmes get the unemployed back to work? a look at the spanish experience”, Revista de Economia Aplicada, 18(53), pp. 39-65.

- Azmat, G., Gűell, M. and Manning, A. (2004), Gender Gaps in Unemployment Rates in OECD Countries. London, Centre for Economic Performance.

- Bachmann, R. and Sinning, M. (2016), “Decomposing the Ins and Outs of Cyclical Unemployment”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 78(6), pp. 853-876.

- Bakas, D. and Papapetrou, E. (2014), “Unemployment by Gender: Evidence from EU Countries”, International Advances in Economic Research, 20(1), pp. 103–111.

- Baussola, M., Mussida, C., Jenkins, J. and Penfold, M. (2015), “Determinants of the gender unemployment gap in Italy and the United Kingdom: A comparative investigation”, International Labour Review, 154(4), pp. 537-562.

- Böheim, R., Horvath, G. T. and Winter-Ebmer, R. (2011), “Great expectations: Past wages and unemployment durations”, Labour Economics, 18(6), pp. 778-785.

- Camarero, M., Carrion-i-Silvestre, J. L. and Tamarit, C. (2008), “Unemployment Hysteresis in Transition Countries: Evidence using Stationarity Panel Tests with Breaks”, Review of Development Economics, 12(3), pp. 620-635.

- Eurostat (2017), [Online] Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database [Accessed 10 07 2017].

- Flek, V., Hála, M. and Mysíková, M. (2015), “Duration dependence and exits from youth unemployment in Spain and the Czech Republic”, Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 28(1), pp. 1063-1078.

- Garcia-Cintado, A., Romero-Avila, D. and Usabiaga, C. (2015), “Can the hysteresis hypothesis in Spanish regional unemployment be beaten? New evidence from unit root tests with breaks”, Economic Modelling, 47, pp. 244-252.

- Gokulsing, D. and Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V. (2014), “Gender, education and labour market: evidence from Mauritius”, The International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 34(9/10), pp. 609-633.

- Khraief, N., Shahbaz, M., Heshmati, A. and Azam, M. (2015), Are Unemployment Rates in OECD Countries Stationary? Evidence from Univariate and Panel Unit Root Tests. [Online] Available at: http://ftp.iza.org/dp9571.pdf

- Koutentakis, F. (2015), “Gender unemployment dynamics: Evidence from ten advanced economies: Gender unemployment dynamics”, Labour, 29(1), pp. 15-31.

- Lyócsa, Š., Výrost, T. and Baumöhl, E. (2011), Unit-root and stationarity testing with empirical application on industrial production of CEE-4 countries. [Online] Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29648/ [Accessed 20 06. 2017].

- Ollikainen, V. (2006), “Gender Differences in Transitions from Unemployment: Micro Evidence from Finland”, Labour, 20(1), pp. 159-198.

- Pašic, P., Kavkler, A. and Boršič, D. (2011), “Gender Disparities in the Duration of Unemployment Spells in Slovenia”, South East European Journal of Economics and Business, 6, pp. 99-110.

- Peiro, A., Belaire-Franch, J. and Gonzalo, M. T. (2012), “Unemployment, cycle and gender”, Journal of Macroeconomics, 34, pp. 1167-1175.

- Queneau, H. and Sen, A. (2007), “Evidence Regarding Persistence in the Gender Unemployment Gap Based on the Ratio of Female to Male Unemployment Rate”, Economics Bulletin, 5, pp. 1-10.

- Queneau, H. and Sen, A. (2009), “Regarding the unemployment gap by race and gender in the United States”, Economics Bulletin, 29(4), pp. 2749-2757.

- Spielmann, C. (2006), “Gender Inequality and Trade”, Review of international economics, 14(3), pp. 362-379.

- Theodossiou, I. and Zangelidis, A. (2009), “Should I stay or should I go? The effect of gender, education and unemployment on labour market transitions”, Labour Economics, 16(5), pp. 566-577.