Introduction

Continuous Improvement (CI) is described by Deming as a philosophy that consists of “Improvement initiatives that increase successes and reduce failures” (Juergensen, 2000; Baghel and Bhuiyan, 2005). The notion of CI is traced back to the Japanese Kaizen idea, which aims to regularly change practices and other things for the better (Imai, 1986). Bessant et al. (2001) argue that, in this unpredictable and complex business environment, it is essential that organisations continually engage in CI efforts. The competitiveness of organisations is not so much assessed by their capital base location, buildings, equipment or the number of their members, but rather by their output products (Bessant et al., 2001).

The CI phrase is linked to different organisational development efforts, which include employee involvement programmes, total quality management (TQM), and initiatives pertaining to customer-related services (Baghel and Bhuiyan, 2005). CI is the “company-wide process of focused and continuous incremental innovation” (Bessant and Caffyn, 1997), which is realised via the effective utilisation of different techniques and tools that are devoted to searching for problem sources, and the exploration of ways to minimise, if not overcome, such problems. Kossoff (1993) argues that CI is attained through the participation of different people at all organisational levels.

Continuous Improvement in Higher Education Institutions

The significance of CI in HEIs relies heavily on those institutions’ importance in the success of individuals, organisations and countries as a whole. Higher education is being challenged to become more responsive, effective and efficient, in the same way that private businesses have been challenged over the past two decades (Alexander, 2000; Cullen et al., 2003; Downey, 2000). The expanding of education worldwide, with students studying in different countries, is causing some concerns for educational institutions, especially the HE sector. In Saudi Arabia, as the majority of universities are public universities, the government, according to Alzhrani et al. (2016), has forced universities to implement modern management styles, including TQM, in order to achieve CI. However, according to Albach and Mazi, (2014), the CI efforts in the Saudi HEIs face a number of challenges, including the sustainability of the educational reforms. In fact, the whole education system in Saudi Arabia is in need for transformative policies in order to improve its outputs. Al-Essa, the Current Minister of Education explains “Our educational system output is still too weak to face the challenges of the present and the future, and we cannot face them without building a versed and capable education system to accommodate the future generations’ ambitions” (Al-Essa, 2016).

Continuous Improvement and organisational Culture

The CI success is largely influenced by the organisational culture (OC) of institutions, which relates to the organisation’s dominant leadership styles, language and symbols, habits and norms, and procedures and rules in practice. Cunliffe (2008) emphasised that The OC has an impact on individuals’ morale, commitment and productivity both of which are essential components for any CI efforts, as well as it shapes the organisation’s image and directs its CI initiatives. A number of studies have emphasised the importance of an encouraging organisational culture in supporting innovation (Van de Vrande et al. 2009) and enhancing effective collaboration (Boschma 2005), both of which are cornerstones for effective CI efforts (Muras and Hovell, 2014 and Palma, 2018). Therefore, for an organization to succeed in its CI efforts, it is vital that they facilitate an effectively encouraging organisation culture.

With that being said, this Paper examines the role of OC in CI in the Saudi HEIs. It specifically aims to provide an understanding of the organisational cultural factors that enable or inhibit the CI. It provides empirical evidence between OC and CI in a developing country’s environment, Saudi Arabia. In the Saudi context, a number CI related studies have been conducted in a number of HEIs in Saudi Arabia (e.g. Sohail and Sheikh 2004; Alsuhaimi, 2012; Alkaraghouli, 2013 and Almurshidee, 2017) and Saudi HEIs organizational culture (e.g. de Boer et al, 2014), however his study will be the first that examines the organisational cultural factors that influence CI within Saudi HEIs. Furthermore, the government as part of its vision 2030 has started taking steps towards the transformation of the Education in Saudi Arabia from different angles. For example, one of the aims of vision 2030 National Transformation Program (NTP) is the moderation of curriculum. Also, the government started reforming its regulations in order to pave the way for investors and the private sector to acquire and deliver educational services (Council of Economic and Development Affairs, 2016). Accordingly, this paper will provide both the government, the universities and those interested in investing in the Saudi HEIs with the organisational cultural factors that are enabling or inhibiting to the CI efforts in the Saudi Universities.

Methodology

This explanatory and interpretive study adopted a qualitative grounded theory approach, which aims to identify the Organisational Culture aspects that have an impact on the CI of Saudi HEIs. OC has been defined by Schein (1992: p. 12) as: “A pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members of the organisation as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.”

The process and methodological techniques inherent within grounded theory were considered suitable for this type of study, as they were likely to provide an in-depth understanding of the study participants’ experiences with CI in HEIs (Birks and Mills, 2011). Since this research is based on the practiced OC of HEIs, it is important to gain a deeper understanding of participants’ experiences. Charmaz (2006) explains that, of all the data collection methods that can be used within a grounded theory methodology, face-to-face interview methods are particularly useful, because meaning is constructed through participant–researcher interactions in order to generate new knowledge. This allowed the gathering of participants’ experiences, including success/failure stories, in order to identify the OC aspects that most enable/inhibit CI.

Data Collection

For this research, open-ended issue focused interviews was adopted since it is beneficial in uncovering the cultural aspect of organisations (Sackmann, 1991). Sackmann contends that, based on her research, an open-ended, issue focused interview design provides a research environment for the study of culture that allows for the retrieval of data that reveals cognitive components such as assumptions and beliefs. These assumptions and beliefs, in that they are interpreted from each organizational member’s cultural frame of reference, represent tacit components of culture within that organization. He further contends that it is this tacit level of culture that must be uncovered to fully understand an organization’s culture because assumptions and beliefs are the foundation for artifacts and behaviour. The interviews conducted assisted in gaining in-depth understanding of how organisational culture will facilitate continuous improvement in Saudi Arabia HEIs.

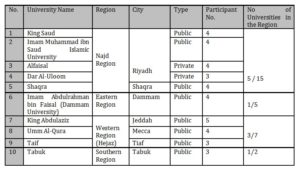

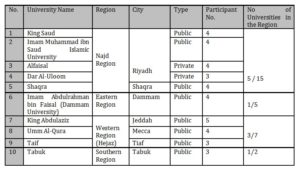

The researcher interviewed 38 respondents over four phases who were selected through chain referral sampling from 10 HEIs in Saudi Arabia. The study analysis showed that after the 33rd interview no more new factors were presented and as such for saturation purposes the following 5 interviews were conducted to confirm that the saturation was satisfied. The interviews were conducted with participants holding different roles in Saudi HEIs, ranging from students to vice presidents. The selected HEIs were geographically distributed across Saudi Arabia, and some were privately owned to ensure that a wider perspective of different cultural settings could be established. The following table (Table 1) provides more details about the study participants and the chosen universities.

Table1: HEIs and participants’ demographics

Data Analysis Process

The analysis of this research’s data has been conducted based on a process of qualitative thematic analysis. Thematic analysis provides a framework that captures the richness of data, and also helps to organise the collected data into a structure (Crabtree and Miller, 1999). Thematic analysis is a method used in identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). According to Boyatzis (1998), thematic analysis can be used as a way of seeing, a way of making sense out of seemingly unrelated material, a way of analysing qualitative information, and a way of systematically observing a person, an interaction, a group, a situation, an organisation or a culture, as well as a way of converting qualitative information to quantitative data.

The data collected were specifically analysed based on Braun and Clarke’s (2006) exhaustive five-stage process: familiarity with data, generating the initial codes, themes development, reviewing themes and the defining and naming of themes.

The researcher started the process of data analysis by familiarising himself with the acquired data, examining the whole mass of data by reading field notes, listening to audio recordings of the interviews a number of times, transcribing the recordings and then reading the transcripts more than once. During this whole familiarisation process the researcher attempted to categorise potentially interesting issues and patterns of meaning, and how they are interrelated; notes were recorded in order to generate ideas for coding.

At the second stage, the researcher began the initial code development of the data. Codes are labels or names allocated to particular segments or units of connected meaning recognised from the transcripts and field notes (Henning et al., 2004; Neuman, 2011). The transcribed text from the field notes (from the researcher’s observations) was organised into meaningful groups using the NVivo software. The process of coding for the transcripts and field notes comprised three stages, as explained by Neuman (2011) and Thiétart (2007); specifically: open, axial and selective coding.

- The first step of open coding involved the researcher’s identification and naming of units of meaning extracted from the transcripts and field notes that relate to the topic of research.

- The second step was axial coding, which was conducted through the review and examination of previously identified codes, followed by the identification of patterns and categories, which have been arranged in terms of context, causality and coherence.

- The final coding step was selective coding, which involved selectively scanning all the identified codes, and contrasting, comparing and linking them to the topic of research in order to develop core categories.

Following this coding process, 62 codes (referred to as aspects in this research) were established. These 62 aspects are described and defined in Table 2 (see appendix A). The inter-ratter evaluation of these aspects was carried out with fellow researchers and the match of 95% was achieved on the sample of 20% of the transcripts.

At the following three stages of themes development and review, and finally the defining and naming of themes, the researcher used a focus group as a means of data analysis. The data analysis has been re-concentrated from codes into the wider level of themes and the focus group critically discussed the list of identified aspects during the interviews; they were then grouped into some sort of meaningful themes. Both the 62 aspects identified from the main data and the extracts from which they were collated were provided to the focus group in advance, giving them sufficient time to read through the OC aspects identified, and to be prepared to discuss them with the rest of the participants in order to develop the themes and their most related aspects. They then, in two phases, discussed and developed and then defined the eight clear distinct themes that represent the research data. Table 3 shows the eight themes alongside their underlying aspects and their definition.

The above outlined qualitative analysis process was a framework utilised to ensure the systemisation of the main data by thematic arrangement, in order to produce comprehensible, consistent patterns of meaning that best represent this research data.

Table 3: Themes developed by the focus group

Results Discussion

The findings of this study suggest eight broad factors that can either encourage or inhibit the CI efforts in Saudi HEIs. These factors do not exist as stand-alone entities, but rather, as will be shown, they co-exist as representations of the CI enabling or inhibiting culture in the Saudi HEIs. Although this study’s findings are based on the Saudi HEIs’ specific data, hence are applicable to the Saudi universities, such findings have – to a certain extent – support in the literature. Therefore, it can be generalised to a certain degree outside the studied area. The study findings are discussed below

This study found that a major influencing factor for the Saudi HEIs’ CI initiatives is in their relationship with society. The participants have explained that Saudi universities are starting to understand the importance of engaging in social activities that benefit society at large. They have cited certain activities that are commonly practiced within Saudi universities, which include concentrated evening skills courses for people who are unemployed or retired, and for soldiers for free or at a limited cost. However, the participants also indicated that the outcome of these courses are less than satisfactory and that such courses have been mainly taken by soldiers and security forces personnel for promotion purposes only, as opposed to the actual enhancement of their skills. This indicates that although the importance of the universities’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been recognised, Saudi HEIs lack the effective understanding and implementation of their CSR. The lack of understanding of CSR is a major issue across many sectors in Saudi Arabia. According to a study by Informa Middle East, whereby they carried out interviews with CSR experts and 150 CSR professionals were surveyed in Saudi Arabia, both groups lacked a proper understanding of what CSR entails (Informa Middle East, 2015).

Furthermore, the participants have indicated that Saudi universities are largely influenced by the society’s hypomanic culture. Cultural hegemony refers to domination or rule achieved through ideological and cultural means (Gramsci, 1978 cited in Cole, 2017). It is the domination of cultural values over the way HEIs operate, through strongly influencing the ideas, values, norms and even the expectations of such institutions. The participants talked about certain cultural practices that are still affecting the learning environment in the Saudi HEIs, which include that male lecturers are not allowed to teach female students face to face, but it has to be through a connected projector, as the lecturer may not be in the same room as his female students.

The finding also reports on the role of the university leaders’ personal relationship with their employees in ensuring the success of any CI efforts. The participants of this study, while describing their experiences with CI initiatives, have emphasized, among other factors, the role of university leaders in acting as good role models, professionally, financially and emotionally supporting their employees, and creating a trust, loyalty and team-orientated work environment in Saudi HEIs. The importance of leaders’ direct behavioural interactions with their employees and the university environment through which such interactions are communicated is supported by the literature. A number of studies have emphasized the leaders’ role in inspiring (Bordum, 2010), motivating and encouraging employees (Gana and Bababe, 2011), facilitating a teamwork environment (Gibson, Porath, Benson & Lawler, 2007) and developing a trust and respect-based work environment (Rico et al., 2011).

Another finding of this study is the participants’ emphasis on the creation of skills, which enhance the organisational culture that supports the CI efforts. The training measures in Saudi universities include exposing their students to foreign education, especially in developed countries, providing training courses for staff in campus and facilitating subject-specific trainings outside the Kingdom. The importance of skills enhancement in the success of institutions is widely supported in the literature. Maruping & Magni (2012) argue that skill enhancement initiatives empower the continuous improvement process by making it more inspiring and dynamic. Delivering continuous skills enhancement in an organisation helps transform continuous improvement into an organisational norm, which has a significant impact on attaining positive outcomes (Seekr, 2011).

The study findings also reported the Saudi universities’ institutional efforts to continually seek internal and external development as an enabler to CI success. The study participants explained that their universities are strengthening their internal capacity with measures such as moderating, integrating and effectively utilising up-to-date technologies. The effective use of technology has gained unsurprising support from all the study participants. It helps academics in their teaching, researching and experimentation; it helps the administrators in quickly and efficiently carrying out their work; and it helps students in their studies. The importance of technology utilisation is further supported by a number of studies, which highlight the use of technology’s importance for both student and employee performance at all levels (see e.g. Zhang et al., 2004 and Rezaei et al., 2014). At the external level, Saudi HEIs are attempting to create external links with governmental entities and other private businesses in order to ensure external support to their development. For example, the participants have explained that there is a tendency in universities to collaborate with governmental bodies or private businesses, and thus attempt to study and provide reasonable solutions for their different issues, while also gaining financially from these services. Such collaboration between practitioners and academics is recognised as not only providing the university with a source of capital, but also, as Rynes and McNatt (2001) argue, that it will enhance the possibility that the emerging research will be relevant and useful to practitioners, and can also be generalised to actual business settings.

This study also reports that a major enabler of the success of CI initiatives is the creation of a strategy-driven work environment. The participants indicated that there is a growing understanding in Saudi HEIs of the importance of creating a strategy for their universities, implementing its provision and working towards achieving its goals. They cited some measures that their universities are taking, which include thinking strategically as they plan for the long term, regularly reflecting upon the progress of their vision implementations, ensuring internal collaboration between different internal university stakeholders and working in partnerships with private business and internationally renowned universities. Their long-term objectives include excellency in graduate skills, excellency in faculty members and research outcomes, and a financially sustainable university. However, this study also finds that the Saudi universities’ strategies examined in this study have failed to plan for any barriers that would arise from the strategies’ proposed changes. Mantere, Schildt, and Silliance (2012) noted that changes within organizations is not as simple as it seems, because strategic changes represent a significant shift in the organisation through changing the usual operation of the business, which could create serious difficulties for management as its not always easily accepted.

The lack of strategies that decrease barriers might have a significant impact on the successful achievement of the institutional strategy and the overall institutional performance. In fact, one of this study’s main findings is the wide-ranging barriers to success that this study’s participants have experienced during their CI initiatives. These obstacles include financial barriers, mismanagement of human resources and employees’ resistance to change. These factors can pose an actual threat to the achievement of the institutional strategy unless they are effectively overcome. If these barriers became an expected norm within the university’s daily functioning, then they can also hamper the university’s overall performance. For example, a number of studies have shown that the lack of financial resources and funding are one of the main reasons for HEIs’ lack of development (Figueredo & Tsarenko, 2013 and Shriberg & Harris, 2012). Financial struggles are also a main reason for students’ anxiety, depression or even suicidal thoughts (McPherson, 2012), and can also result in low academic performance (Ross et al., 2006). Also, Talebian (2000) states that ineffective management of human resources has a negative effect on workplace productivity as it leads to the hiring of unqualified, incompetent employees, which would significantly impact the efficiency of their work. Employee change resistance has also a significant impact on successful CI implementation. According to Egan and Fjermestad (2005), employee change resistance is a prime reason why most changes do not succeed or get implemented. Haslam et al. (2004) further argue that the top obstacle to change is employee resistance at all levels.

Form an ethical point of view, the study reports on ethical violations within HEIs in Saudi Arabia that are considered major inhibitors to their CI success. These ethical violations include lack of equality between employees, lack of equity and abuse of power. These ethical violations not only create institutional “suspicion and criticism”, which according to Kelley et al. (2006) would “undermine the reputation of universities” and their credibility (Yeo & Chien, 2007), but will most certainly adversely affect its CI efforts. A number of studies have found that ethical violations would have an effect on the job productivity of employees (Brief, 1998), employees’ job satisfaction (Brown, 1996), employees’ team work and job effectiveness (Hu and Liden, 2015); it would also increase employee turnover (Griffeth et al., 2000) and affect employees’ relationship with their managers (Latif et al., 2015).

The participants also expressed their concerns with the current cultural infrastructure within Saudi HEIs. According to Pakdil and Leonard (2015), a number of organisational factors form the organisation’s cultural infrastructure, which include “employee involvement, creativity, problem-solving processes, decentralisation, control and standardisation, efficiency and productivity”. The participants explained that the current cultural infrastructure in the Saudi HEIs is (among other things) very bureaucratic and lacks productivity. The negative influence of work bureaucracy is supported by many researchers. Beetham (1996) argues that the adherence to bureaucratic norms can hamper efficiency. The bureaucratic tendency to have a control of individuals’ activities and to restrict their autonomy adversely affects employees’ work spirit and suppresses their creativity (du Gay, 2000), therefore hindering innovation (Daymon 2000), which is essential for the survival of HEIs.

Other than bureaucracy, other factors have allowed the creation of unproductive work environments, which according to this study’s participants has become a norm in Saudi HEIs. In fact, employees’ productivity is a major issue throughout the whole public sector in Saudi Arabia. According to a statement by the former labour minister, “The productivity of the Saudi employee does not exceed one hour, according to a study by the Economic and Planning Ministry” (Alkhalisi, 2016). However, it is believed that employees’ productivity is a cornerstone for not only the competitiveness and continuous improvement of HEIs, but also their overall survival (Pritchard, 1995).

The participants also indicated that physical infrastructure is another major factor in the success of CI in HEIs. Physical infrastructure is defined as “those resources and facilities necessary to the development and delivery of educational programmes”. There are different cited essential resources and facilities that are not found in some Saudi universities, which include libraries, engineering laboratories and even enough classrooms. It is believed that such resources are essential to create a cultural infrastructure that supports CI initiatives. A number of studies have shown the direct links between the physical resources and the learning outcomes (Vieluf et al., 2012; Trang and Lap, 2016). The lack of available and adequate HEIs facilities influences the employees’ professionalism (Rivera-Batiz, and Marti, 1995) and their overall job performances (Knirk, 1992).

Conclusion and Implications

The results of this empirical study show an overall lack of effective organisational culture that supports the CI efforts in the Saudi HEIs. The findings show that the current university infrastructure in Saudi Arabia goes against the whole idea of pursuing CI. The Bureaucracy, lack of productivity, lack of strategic thinking, lack of staff development, and lack of essential study facilities like libraries and suitable classrooms are examples of the success inhibiting infrastructure in the Saudi HEIs. Furthermore, the lack of equality in Saudi HEIs is another contributor to lack of effective organisational culture. The lack of fair treatment and equal access to opportunities for the university employees, and the mismanagement of the University Human resources, among others, are major contributing factors to the failure of the success of any CI initiatives. It is therefore recommended that further research should be conducted to develop a series of realisable interventions that address these factors in order to ensure effective OC that supports the CI initiatives in Saudi HE

Appendix A

Table 2: The Organisational Culture Aspects

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Al-Essa, A. (2016). ‘Our Education to where’. [Online]. Alhayah Newspaper. [Retrieved December 15, 2017]. Available: http://www.alhayat.com/article/840881/تعليمنا-لى-أين . IN Arabic

- Alexander, F. K. (2000). The changing face of accountability. The Journal of Higher Education, 71(4), 411-431.

- Alkhalisi, Z. (2016). How many Saudis are only working one hour a day? [online] Available at:http://money.cnn.com/2016/10/20/news/saudi-government-workers-productivity/index.html [Accessed October 29, 2016].

- Alzhrani, K.; Alotibie, B & Azrilah, A. (2016). ‘Total Quality Management in Saudi Higher Education.’ International Journal of Computer Applications. Volume 135 – No.4

- Baghel, A., & Bhuiyan, N. (2005). ‘An overview of continuous improvement: from the past to the present,’ Management Decision, 43 (5), 761-771.

- Beetham, D. (1996). Bureaucracy, Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Bessant, J. & Caffyn, S. (1997), “High-involvement innovation through continuous improvement”, International Journal of Technology Management,14, no.1, pp. 7-28

- Bessant, J., Caffyn, S. & Gallagher, M. (2001), “An evolutionary model of continuous improvement behaviour”, Technovation, vol.21, no.2, pp. 67-77

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2011). Grounded theory: A practical guide. London, England: Sage.

- Bordum, A. (2010). ‘The strategic balance in a change management perspective’. Society and Business Review. 5 (3). pp. 245–258

- Boschma, R. (2005). ‘Proximity and innovation: a critical assessment,’ Studies, 39, 61–74

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998): Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publication

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006). ‘Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology’ Qualitative Research in Psychology; Vol. 3; No. 2; pp. 77-101.

- Brief, A. P. (1998). Attitudes In and around organizations. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Brown, Mark G. (1996). Keeping Score: Using the Right Metrics to Drive World-Class Performance. New York: Quality Resources.

- Charmaz, K (2006): Constructing Grounded Theory: a Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis, London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Cole, N. (2017) Definition of Cultural Hegemony, How the Ruling Class Maintains Power Using Ideas and Norms, Thought Co. [online] [Retrieved September 12, 2017 from https://www.thoughtco.com/cultural-hegemony-3026121

- Crabtree, B.F., and Miller, W.L. (1999). “Using Codes and Code Manuals: A Template Organizing Style of Interpretation.” In: Doing Qualitative Research in Primary Care: Multiple Strategies (2nd Edition), Crabtree, B.F., and Miller, W.L.

- Cullen, J. Joyce, J. Hassall, T. and Broadbent, M. (2003), “Quality in Higher Education: from monitoring to management”, Quality Assurance in Education. Vol. 11, No.1, pp.5-14

- Daymon, C. (2000). ‘Cultivating creativity in public relations consultancies: the management and organisation of creative work’. Journal of Communication Management. 5/1; 17-30.

- Downey, T. E. (2000). The application of continuous quality improvement models and methods to higher education: Can we learn from business? (No. ED447291).

- Du Gay, P. (2000). In Praise of Bureaucracy. London: Sage.

- Egan, R. W., & Fjermestad, J. (2005). ‘Change and Resistance Help for the Practitioner of Change’. System Sciences, 2005. HICSS ’05. Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on, 219c-219c.

- Figueredo, F. R., & Tsarenko, Y. (2013). ‘Is “being green” a determinant of participation in university sustainability initiatives?’ International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 14 (3), 242-253

- Gana, A. B. and Bababe, F. B. (2011). “The Effects of Motivation on Workers Performance (a case study of Maiduguri Flour Mill Ltd. Borno State, Nigeria.),” Continental J. Social Sciences 4 4 (2): pp. 8 – 11.

- Gibson, C.B., Porath C.L., Benson, G.S., & Lawler, E.E. (2007).’ What results when firms implement practices: The differential relationship between specific practices, firm financial performance, customer service, and quality’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1467-1480

- Gramsci, A. (1978). Selections from Cultural Writings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Griffeth RW, Hom PW, Gaertner S (2000). “A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium”, Journal of Management. 26 (3): 463-88

- Haslam, S. & Pennington, R. (2004). ‘Reducing resistance to change and conflict: A Key to Successful Leadership’ Resource International, 3-9.

- Henning, E., Van Rensburg, W. & Smit, B. 2004. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik

- Hu, J. and Liden, R. (2015). ‘Making a Difference in the Teamwork: Linking Team Prosocial Motivation to Team Processes and Effectiveness’. Academy of Management Journal, 58 (4), pp. 1102-1127

- Imai, M. (1986). Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success, McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, New York NY

- Informa Middle East, (2015) ‘Top CSR Trends in Saudi Arabia’ (The Informa review, 14 January 2015) [Online] http://blog.informa-mea.com/top-csr-trends-in-saudi-arabia/ [Retrieved October 20, 2017].

- Juergensen, T. (2000), Continuous Improvement: Mindsets, Capability, Process, Tools and Results, [Online] The Juergensen Consulting Group, Inc., Indianapolis, IN. [Retrieved December 12, 2016], http://www.scirp.org/(S(oyulxb452alnt1aej1nfow45))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1906551

- Kelley, P., Agle, B., & DeMott, J. (2006). ‘Mapping our progress: Identifying, categorizing and comparing universities’ ethics infrastructures’. Journal of Academic Ethics, 3 (2), 205-229.

- Knirk, F.G. (1992). ‘Facility requirements for integrated learning systems’. Educational Technology 33 (9), 26-32.

- KOSSOFF, L. (1993), “Total quality or total chaos?” HR Magazine, Vol. 38 No. 4, pp. 131-4.

- Latif, M.S., Ahmad, M., Qasim, M., Mushtaq, M., Ferdoos, A.,& Naeem, H. (2015). ‘Impact of employee’s job satisfaction on organizational performance’. European Journal of Business and Management, 7, 166–171

- Mantere, S., Schildt, H.A. and Sillince, J.A. (2012). ‘Reversal of strategic change’. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1): 173–196.

- Maruping, L. M., and Magni, M. (2012) ‘What’s the Weather Like? The Effect of Team Learning Climate, Empowerment Climate, and Gender on Individuals’ Technology Exploration and Use,’ Journal of Management Information Systems, 29, 1, 79–114.

- McPherson, A. V. (2012). College student life and financial stress: An examination of the relation among perception of control and coping styles on mental health functioning. (Doctoral dissertation, North Carolina State University). [Retrieved October 12, 2016] from http://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/i

- Muras, A., & Hovell, J. (2014). ‘Continuous Improvement Through Collaboration, Social Learning, and Knowledge Management’. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 25(3), 51–59.

- Neuman, W.L. (2011). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches 7th (International), ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon

- Palma, H.H., Atlántico, U. & E, P.A. De (2018). ‘Continuous Improvement for Colombian Universities through Innovation in Information Management’. Contemporary Engineering Sciences, 11 (83). pp. 4095–4103.

- Pakdil, F. and Leonard, K. M. (2015) ‘The effect of organizational culture on implementing and sustaining lean processes’, Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 26(5), pp. 725–743

- Pritchard, R. D. (1995). Productivity measurement and improvement: Organizational case studies. New York: Praeger.

- Rezaei, M., Zare, M., Akbarzadeh, H. & Zare, F. (2014). ‘The Effects of Information Technology (IT) on Employee Productivity in Shahr Bank (Case study of Shiraz, Iran).’ Applied Mathematics in Engineering, Management and Technology. pp. 1208–1214.

- Rico, R., María, C., De, A. & Tabernero, C. (2011). ‘Work Team Effectiveness, a Review of Research. Psychology in Spain, 15 (1). pp. 57–79.

- Rivera-Batiz, F.L. & Marti, L. (1995). A school system at risk: A study of the consequences of over- crowding in New York City public schools. New York: Institute for Urban and Minority Education, Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Ross, S., Cleland, J., & Macleod, M. J. (2006). ‘Stress, debt and undergraduate medical student performance’. Medical Education, 40(6), 584-589

- Rynes, S. L., & McNatt, D. B. (2001).‘Bringing the organization into organization research: an examination of academic research inside organizations’. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16 (1), 3-19

- Sackmann, S. a. (1991). ‘Uncovering Culture in Organizations’. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(3), 295–317.

- Council of Economic and Development Affairs, (2016). ‘ Saudi Vision 2030’. [Online]. [Retrieved September 10, 2017] Available: http://vision2030.gov.sa/download/file/fid/417

- SCHEIN, E.H. (1992). Organizational culture and Leadership (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Seekri, B. (2011) Organizational Turnarounds with a Human Touch. Bloomington, Indiana: Trafford.

- Shriberg, M., & Harris, K. (2012). ‘Building sustainability change management and leadership skills in students: lessons learned from “Sustainability and the Campus” at the University of Michigan,’ Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2 (2), 154–164.

- Talebian, A. R. (2000). Organizational structural factors affecting labor productivity, Thesis, Tehran University. Tehran

- Thiétart, R. ed. 2007. Doing management research: A comprehensive guide. London: SAGE

- Trang, D.D. and Lap, T.Q., (2016). ‘Lecturers and students’ perception of efl policy and practice at a higher education institute,’ Can Tho University Journal of Science, Vol. 3: 49-56.

- Van de Vrande, V., De Jong, J.P., Vanhaverbeke, W., De Rochemont, M. (2009). ‘Open innovation in SMEs: trends,motives and management challenges,’ Technovation, 29,(6) 423–437

- Vieluf, S., Kaplan, D., Klieme, E., and Bayer, S., (2012) Teaching practices and pedagogical innovation: Evidence from TALIS. OECD Publishing

- Yeo, S., & Chien, R. (2007). ‘Evaluation of a process and proforma for making consistent decisions about the seriousness of plagiarism incidents,’ Quality in Higher Education, 13 (2), 187-204

- Zhang, D. J. L; Zhao, L.; Zhou, J.F. & Nunamaker, Jf. (2004) ‘Can e-learning replace classroom learning? Communication of the ACM, 47 (5), pp. 75-79.